Graphic Design: The New Basics: Second Edition, Revised and Expanded (2015)

Beyond the Basics

Jennifer Cole Phillips

Even the most robust visual language is useless without the ability to engage it in a living context. While this book centers around formal structure and experiment, some opening thoughts on process and problem solving are appropriate here, as we hope readers will reach not only for more accomplished form, but for form that resonates with fresh meaning.

Before the Macintosh, solving graphic design problems meant outsourcing at nearly every stage of the way: manuscripts were sent to a typesetter; photographs— selected from contact sheets—were printed at a lab and corrected by a retoucher; and finished artwork was the job of a paste-up artist, who sliced and cemented type and images onto boards. This protocol slowed down the work process and required designers to plan each step methodically.

By contrast, easily accessed software, cloud storage, ubiquitous wi-fi, and powerful laptops now allow designers and users to control and create complex work flows from almost anywhere.

Yet, as these digital technologies afford greater freedom and convenience, they also require ongoing education and upkeep. This recurring learning curve, added to already overloaded schedules, often cuts short the creative window for concept development and formal experimentation.

In the college context, students arrive ever more digitally adept. Acculturated by social media, smart phones, iPads, and apps, design students command the technical savvy that used to take years to build. This network know-how, though, does not necessarily translate into creative thinking.

Too often, the temptation to turn directly to the computer precludes deeper levels of research and ideation—the distillation zone that unfolds beyond the average appetite for testing the waters and exploring alternatives. People, places, thoughts, and things become familiar through repeated exposure. It stands to reason, then, that initial ideas and, typically, the top tiers of a Google search turn up only cursory results that are often tired and trite.

Getting to more interesting territory requires the perseverance to sift, sort, and assimilate subjects and solutions until a fresh spark emerges and takes hold.

Visual Thinking Ubiquitous access to image editing and design software, together with zealous media inculcation on all things design, has created a tidal wave of design makers outside the profession. Indeed, in our previous book, D.I.Y.: Design It Yourself, we extolled the virtues of learning and making, arguing that people acquire pleasure, knowledge, and power by engaging with design at all levels.

This volume shifts the climate of the conversation. Instead of skimming the surface, we dig deeper. Rather than issuing instructions, we frame problems and suggest possibilities. Inside, you will find many examples, by students and professionals, that balance and blend idiosyncrasy with formal discipline.

Rather than focus on practical problems such as how to design a book, brochure, app, or website, this book encourages readers to experiment with the visual language of design. By “experiment,” we mean the process of examining a form, material, or process in a methodical yet open-ended way. To experiment is to isolate elements of an operation, limiting some variables in order to better study others. An experiment asks a question or tests a hypothesis whose answer is not known in advance.

Choose your corner, pick away at it carefully, intensely and to the best of your ability and that way you might change the world. Charles Eames

The book is organized around some of the formal elements and phenomena of design. In practice, those components mix and overlap, as they do in the examples shown throughout the book. By focusing attention on particular aspects of visual form, we encourage readers to recognize the forces at play behind strong graphic solutions. Likewise, while a dictionary presents specific words in isolation, those words come alive in the active context of writing and speaking.

Filtered through formal and conceptual experimentation, design thinking fuses a shared discipline with organic interpretation.

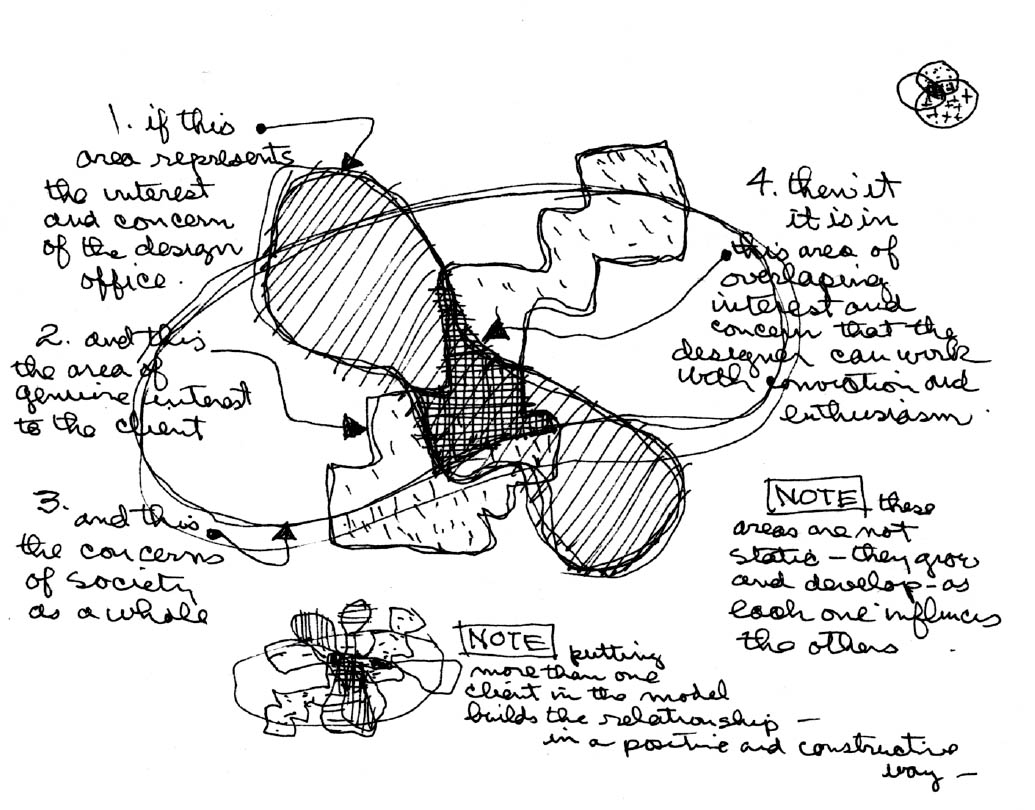

Diagramming Process Charles Eames drew this diagram to explain the design process as achieving a point where the needs and interests of the client, the designer, and society as a whole overlap. Charles Eames, 1969, for the exhibition What is Design at the Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, France. © 2007 Eames Office LLC.

Photo Constructions Designer Martin Venezky made this image of reconstructed details from a large collage wall he generated in a three-day formstorming exercise for All Possible Futures, an exhibition by Jon Sueda. Martin Venezky, Appetite Engineers.