Manage Your Pain: Practical and Positive Ways of Adapting to Chronic Pain - Michael K. Nicholas, Allan Molloy, Lee Beeston, Lois Tonkin (2012)

Chapter 13. Attentional Techniques - Distraction and Desensitising

Summary:

✵ Many people use distraction to cope with their pain.

✵ But distraction is only one of many possible mental techniques that involve using your attention. We call them attentional techniques as a group.

✵ They won’t remove the pain completely, but they can take the edge off it.

✵ Combining desensitising with other activities can help you to keep active.

✵ We recommend you should apply them whenever you feel your pain is starting to bother you.

✵ Three strategies are outlined, but they all need practice to develop into useful tools.

✵ Try each one to work out which suit you best; you may find one suits better in one situation while another suits you better in other situations.

1. Focus your attention away from the pain (Distraction)

These techniques work best if you can involve as many of your senses as possible. This means using your senses of sight, hearing, smell, temperature and touch, all at once. By really getting involved in this way you will find it easier to block out the pain signals.

· Imagine a pleasant, relaxing scene. Imagine you are really there. Focus on what you can see, hear, smell and feel - the colours around you; the sound of the sea, or birds; the warmth of the grass or sand under your body, and so on. It may be a favourite place, by the sea, in the countryside or in your garden. If it was a time or place you associate with happy feelings, try to recall those too. But make sure you don’t start to focus on any sad feelings, such as dwelling on how unhappy you have been since that time or how you can’t go back to those days.

· Plan something you can look forward to, such as a holiday, changes to your house or garden, or an evening entertaining friends. Dwell on the pleasant aspects, and expand on all the details. Make it as real as possible.

· Bring to mind someone important to you, perhaps a member of your family or a friend whom you would very much like to see. Make a clear picture of him or her in your mind’s eye, and imagine you’re having a chat. [Make sure you do not start talking about pain!]

· Focus your mind on something you can see, using it to block out awareness of anything else. It could be a pain-free part of your body, a picture on the wall, other people around you, the scene outside your window.

· Try recalling the plot and characters, in a favourite book or one you are reading at present. Build up as much detail as you can manage.

· Recite poetry, or a song - one you particularly enjoy, and is calming.

You may have some distraction ideas of your own. Try them too.

2. Imagine Scenes Which Include The Pain, But Focus On Pleasant Or Exciting Aspects Of The Scene.

· Create an exciting and inspiring scene in which you are over-riding your pain in order to achieve a greater goal - running the last stretch of the marathon, winning a tennis match, scoring a goal in a football final, or getting to the top of Mt Everest without oxygen.

3. Focus on the Pain Itself (to desensitise yourself to your pain)

At first glance this technique may seem to go against ‘common sense’ as it involves letting yourself feel the pain rather than trying to get away from it. To help it make more sense, think about why we get pain to start with. Broadly speaking, acute pain is a warning signal. It warns us that something is wrong, we may have an injury or be about to have an injury. Acute pain lets us know we need to investigate the cause and do something about it. Such pain can be useful to us. But that does not apply to chronic pain.

In contrast, with chronic pain any damage has already been done, so it’s not really telling us anything new. The possible cause of your chronic pain will have been extensively investigated and you should have been reassured that serious or life-threatening causes have been ruled out. You can tell yourself that you are physically OK and not in danger.

Earlier in the book we mentioned that one of the main mechanisms involved in chronic pain is a process called Central Sensitisation. This means that harmless nerve signals can be experienced as pain. The trouble is, our brain may still see the pain as a threat, just like acute pain. Unfortunately, just telling yourself the pain is OK is unlikely to be enough to overcome chronic pain. We have found that you also need to train your brain to learn not to react to this chronic pain as if it is acute pain.

How do we train our brain to learn this new skill? Just like any other training - by practising it (a lot).

To desensitise yourself to your chronic pain you need to:

1. Accept that it is not harmful and that it is OK to start moving.

2. Try not protecting yourself against the pain.

3. Acknowledge the pain is there but don’t react to it.

This requires that you don’t try to avoid or escape the pain. The normal response to ongoing pain is to try to get away from it or to distract yourself from it - that is why people take pain killers. But what would happen if you didn’t try to get away from it? Remember, you’ll have the pain anyway. Why not see what happens if you don’t try to escape the pain?

Another way of looking at our response of trying to avoid or escape from pain is to compare it with what we might do when we are afraid of something that is not really dangerous. For example, if we have a fear of heights we might avoid going to high places, even though it is very unlikely that we would fall off. By avoiding heights, we may never learn that we’d be OK after all. That fear can also limit our lifestyle. Interestingly, we know that the best treatment for these sorts of fears is confronting whatever you are afraid of (like going up to a high place) and letting yourself feel the anxiety sensations without reacting. It may take a few sessions of repeating this, but if you keep at it consistently, the method will work and you will overcome the fear. This effect can be called desensitisation or habituation (getting used to something).

Habituation is something we have all experienced. For example, if you buy a new painting or poster and put it on your wall you will notice it and admire it whenever you walk past initially. But after a few weeks you notice it less. It will start to become part of the background. You remain aware that it is there, you just don’t notice it as much. This effect is called habituation. If we weren’t able to do it we would be constantly distracted by everything we walked past. To become habituated to something we must not try to avoid or escape from it. Repeatedly trying to escape from or avoid something keeps us more sensitive to it. We are at risk of always being ‘on the look-out’ for it. It is not difficult to see how this can apply to pain.

What if we took the same approach to chronic pain? Instead of trying to avoid it or escape from it, what if we deliberately faced it for an extended period? This would mean accepting the presence of pain without trying to minimise it with medication.

We have been trying this method with our patients for many years. After a while, those who practise it a lot find the pain doesn’t bother them as much. Of course, it’s not easy for everyone and some say they can’t face even the idea of doing it. In those cases one-to-one sessions with a psychologist may be needed to master it. But overall, we have found this method very helpful in lessening the distress caused by pain. The pain will remain but you can train yourself to be less bothered by it.

We recommend you practice focussing on the pain in this way whenever your pain starts to trouble you. A good time to practice is when you are exercising or doing other activities that can aggravate your pain. Try it when you are trying to go to sleep and feel you can’t get comfortable.

To begin with, you might like to combine it with your relaxation practice. Start with a mix of long and short sessions. We recommend two or three twenty minute sessions a day. In between, you should try brief sessions (1-2 minutes) whenever you notice your pain through the day, as when you are exercising. After a few weeks it will become a habit and you will find yourself doing it without realising it.

Start by letting go and calming yourself with your relaxation technique, but focus your attention on your pain. Focus on your pain as calmly as possible. Make no effort - just allow yourself to feel the pain sensations without reacting to them. You can even imagine you are immersing yourself in the pain, like getting into the water at the beach or pool - remember how it often seems hard to start with but after a few minutes our body adjusts. Desensitising is a similar process, but you are learning to adjust to an internal sensation.

Most importantly, you don’t need to think. Just observe the sensations for what they are - sensations with no real meaning and they are not harming you. Try not to block the pain or even think about how bad it is. You can’t stop yourself thinking but you don’t have to respond to the thoughts. Just let any thoughts pass you by. It is especially important to avoid cursing the pain - that risks giving it a special status and extra power. Just calmly focus on that sensation you call pain and see what happens.

You can keep reminding yourself that you are OK and the pain doesn’t mean anything, just harmless signals in your nerves.

Try to keep your attention on the pain. Don’t try to change the pain or even try to make it go away - as that is still trying to escape from it. Calmly, let it be there and continue relaxing.

Initially, the pain may start to feel more severe. This just because you’re used to trying to get away from it, but this effect will pass. Try not to let it stop you. Remind yourself that it can’t cause you any damage. You are OK. Keep going because it won’t continue getting worse. Any increase in pain will settle (after all you are not doing anything that can harm you).

After each session spend a minute or so thinking about what you noticed. Try not to measure it in terms of ‘did it work’ or ‘did it make the pain go away’, rather what did you notice? Compare that with the last time you did it. Over time you should start to notice changes in the way you experience your pain at these times. You might like to experiment with the technique.

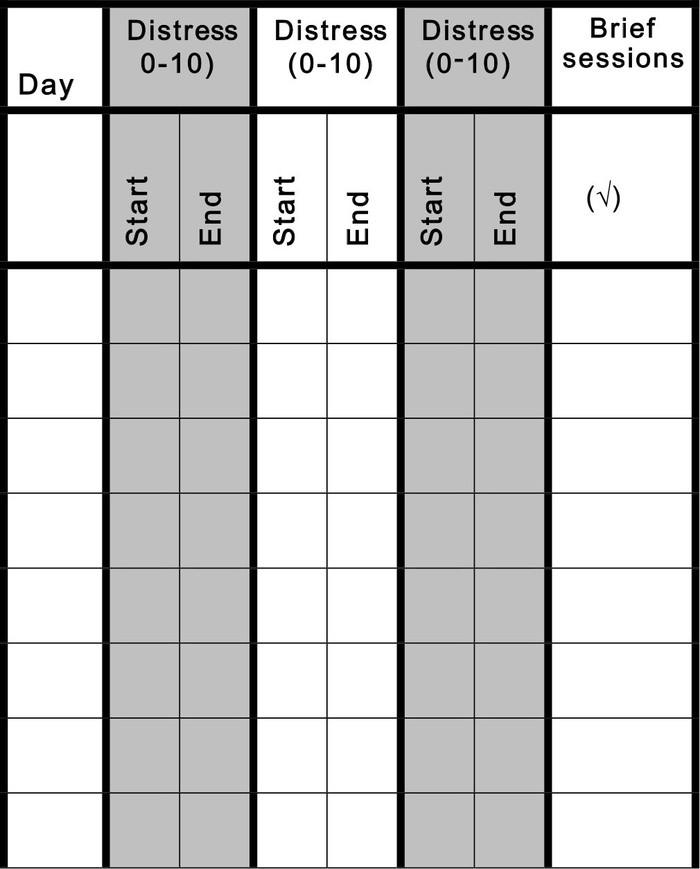

It can help you to get into regular practice by keep a record of how much your pain bothers you before and after each session. Make a copy of the recording form like this one below:

As you get better at the technique try using it to counteract your pain whenever you find it starting to intrude.

One word of caution. We don’t recommend that you use the technique to over-ride your normal pacing of activities. You should continue to pace activities that aggravate your pain, but use the desensitising technique to cope with your pain whenever it starts to trouble you.

Pain Desensitisation Record Sheet

Please rate how much the pain bothers you before and after each long session (3/day).

Rate how much it bothers you from 0-10, where 0 = ‘does not bother me at all’ and 10 = ‘extremely distressing’).

Place a tick (✓) in the last box for all brief sessions.

Overall, it is best to approach these techniques as realistically as possible - don’t expect too much too soon - but do try each of them as often as possible. After a while you will find one or two will be quite helpful at times, providing you remember to go on using them. Including these techniques in your relaxation practice is often a good way to start, but relaxing first isn’t essential. You’ll find that as you get better at desensitizing you also become more relaxed when feeling your pain.