Four Ways to Click: Rewire Your Brain for Stronger, More Rewarding Relationships (2015)

Chapter 5

C IS FOR CALM

Make Your Smart Vagus Smarter

Signs that a relationship strengthens your Calm pathway:

I trust this person with my feelings.

This person trusts me with his feelings.

I feel safe being in conflict with this person.

This person treats me with respect.

In this relationship, I feel calm.

I can count on this person to help me out in an emergency.

In this relationship, it’s safe to acknowledge our differences.

It feels terrible to be tense and irritable. Imagine what life was like for Juan, who felt tense and irritable all the time. On the Monday morning before I met Juan, he woke up feeling even worse than usual. He’d stayed up late watching football with a couple of friends the night before. They drank too much and ate too much, and his favorite team lost in overtime. The next morning, electric surges of rage shot through his body. He was angry about the game, and he was angry in general. Just the sound of toast crunching in his mouth threatened to push him over the edge. Juan considered calling in sick to his job as a computer programmer, but he was working on a new team project and the first meeting was scheduled for ten a.m. He showered and walked to the subway.

When he arrived at work, Juan could feel the tension building inside him. When he felt this way, the people around him seemed to become incredibly stupid. He didn’t want to deal with their questions or hear stories about their weekends, so he sorted through his e-mail with earphones on, hoping no one would try to talk to him. But a new employee, Veronica, approached from behind and tapped him on the shoulder. He jolted from his chair, surprising them both. He sat down quickly and told her to leave him alone.

Juan hated meetings, particularly large team meetings intended to let everyone hear everyone else’s thoughts about a new project. On a good day, Juan could barely sit through a meeting as people “threw out” their ideas. On a bad day, he rolled his eyes, snorted, or zoned out. In each of his evaluations at the company, Juan’s boss praised him for his sharp analytic mind and computer skills but repeatedly told him he needed to change his attitude, his lack of interpersonal skills would prevent him from moving up. To Juan, this feedback felt like an attack, and another example of other people’s annoying behavior.

Juan entered the meeting room ten minutes late, hoping to miss the opening chitchat. As his colleagues went around the table and described their thoughts about the project, Juan struggled to keep his patience. This felt like an unnecessary, self-indulgent step, aimed to please his touchy-feely boss. When Juan’s turn came to “share,” he gave a brief, monotone description of his role in the project, making eye contact with no one.

Midway through the meeting, Juan was asked how they might add new graphics to an existing demo product. His boss had told him that colleagues valued his skills; that’s why they routinely turned to him with difficult problems. He enjoyed using his analytic mind to quickly break down even the most difficult problems and come up with plans that usually stunned his colleagues. But after Juan shared his ideas, a more junior member of the team spoke out, questioning the advice Juan had just given and suggesting an alternative approach. The electricity surged again, and Juan snapped. Furious, he stood up at the table and berated the young man. When Juan stopped yelling, the room was deathly quiet—until his boss asked him to leave the meeting. Juan stormed out of the room, slamming the door behind him. Later that morning his boss suggested Juan leave for the day and return to meet with him the next morning. Juan left the building, afraid he had gone too far this time and was likely to lose his job. But he didn’t lose his job, as he found out the next day: he was referred to me for counseling.

✵ ✵ ✵

When I met Juan, I was struck by his inability to sit still. Some part of his body was always in motion. For most of our meeting, his right leg bounced rhythmically. He picked at his fingers. He chewed gum, too—not a slow, relaxed chew but the kind of intense chewing you see in baseball players during a game. I could see the muscles of his jaw tighten over and over again. Despite this activity, Juan didn’t look animated. He looked exhausted.

Juan knew that family members and coworkers described him as a hothead and that he reacted to many interpersonal exchanges with impatience. He appreciated that his job allowed him to spend hours interacting with his computer and not with people. He did occasionally have lunch with a colleague, but more often than not he ate at his desk, working comfortably between bites.

As we talked, Juan groaned and shook his head, looking at the floor.

“You groaned,” I said. “What was that about?”

“I really don’t want to be that guy,” he said. “The Computer Guy with Anger Issues.”

In truth, a lot of people suffer from jumpiness and irritability, and they work in all kinds of professions. Some are able to make it through the workday without exploding; these people often save up their tension for the unfortunate family members who wait for them at home. Some people aren’t hostile at all, but they find interpersonal interactions so stressful that they want to jump into bed and pull up the covers after a trip to the grocery store. Some drink. A lot. (These are the people who need to “take the edge off.”) I’ve always suspected that all these folks are underrepresented in therapy offices, in part because therapy sounds like fifty long minutes of irritating interaction, but also because they fear labels. Something is terribly wrong with you, they imagine me saying. Here, let me show you this textbook that explains the word for people who can’t handle being around others.

But every person who’s come to my office has been endlessly complex and interesting—and shorthand labels, even diagnoses, can never capture a soul’s complexity. There’s no judgment here: people with chronic interpersonal stress are usually relieved to know that their tension is not a character flaw or a personal failure. It’s simply a problem with the Calm neural pathway. Specifically, this kind of constant relational stress is related to low tone in the smart vagus. Low vagal tone makes it hard to feel relaxed in the presence of others.

The autonomic nervous system contains three branches that help you react appropriately to threats: the sympathetic nervous system, which stimulates the fight-or-flight response when you are in danger; the parasympathetic nervous system, which brings on the freeze response when your life is threatened; and the smart vagus, which has the power to block the fight, flight, and freeze responses when you are feeling safe. At one end, the smart vagus feeds directly into the muscles of facial expression, vocalization, and swallowing, as well as the tiny muscles of your inner ear. At the other end, the smart vagus innervates the heart and lungs. When the smart vagus is working the way it should, it can “see” friendly expressions on the faces of people around you and “hear” warm voices. At these signals, the heart and lungs slow down into a relaxed pattern. In effect, the smart vagus has the power to tell the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems: I’ve surveyed the territory and things are okay. Your stress responses are not needed right now; it’s safe to relax. If the smart vagus doesn’t get that input, it sends a different message: The world looks pretty dangerous out there. Probably a good idea for you to mobilize, in case something bad goes down.

I’ve mentioned that although the neural pathways for connection are constantly shaping themselves through your relationships, it’s during childhood when these pathways are most malleable. The smart vagus needs stimulation from caring faces and voices in order to wire together with networks of nerves that associate that visual and audio input with safety. It needs to experience the relational qualities, like trust and the ability to feel safe during conflict, that strengthen the Calm pathway. Most important, the smart vagus—like a muscle—needs to be used to develop good tone. When that doesn’t happen, the smart vagus doesn’t grow strong, and it doesn’t learn to associate relationships with serenity and safety. A person with low vagal tone may intellectually understand that he is surrounded by supportive, encouraging people and still feel terribly threatened around those same people, because his smart vagus isn’t able to tell his stress-response systems to stand down. When vagal tone is very low, all relationships feel threatening.

Juan’s smart vagus pathway was still under construction when, at age six, his mother died in a fiery car crash. His father, who was busy trying to keep his auto-body business afloat, had little time to nurture and care for his six children. Although Juan’s sister, Blanca, tried to raise him, she was young herself—only twelve years old—when their mother died. And neither was able to protect themselves from their father, who yelled at them and sometimes hurt them. Instead of being exposed to soothing parental expressions, Juan became skilled at reading a different set of emotions. When his father came home with his eyes narrowed and his mouth pressed into a line, Juan knew to tread lightly and stay out of his father’s way. When his father started yelling before even entering the house, Juan understood that it was time to take cover. On those nights, Juan wasn’t sure he would live to see the morning. Juan’s nervous system developed in a manner that was appropriate to this environment. His sympathetic nervous system was on almost all the time, its nerve pathways becoming muscular and efficient, while his smart vagus withered from disuse.

There was one reliable way Juan could relax and feel safe, and that was when he was alone. Studying computers was a godsend: the intricacies fascinated his detail-oriented brain, and there was little interpersonal interaction. When someone did approach him, even if just for a conversation, his body reacted with a surge of adrenaline, followed by anger or fear. Early in life, he learned the route to staying safe and to minimizing those unsettling surges of stress: avoid people whenever possible.

As Juan became an adult, he had more control over the safety of his immediate world. But he still had an overprotective nervous system with a powerful fear response, and it was a significant barrier to healthy relationships. Nevertheless, Juan did have a social life. He still spent time with his family, even his father, and felt close to Blanca. He had a best friend, Bob, and they hung out with a small circle of friends. Juan dated quite a bit, though he’d had only one long-term relationship. That ended when his girlfriend decided she could no longer take Juan’s reprimands and lectures.

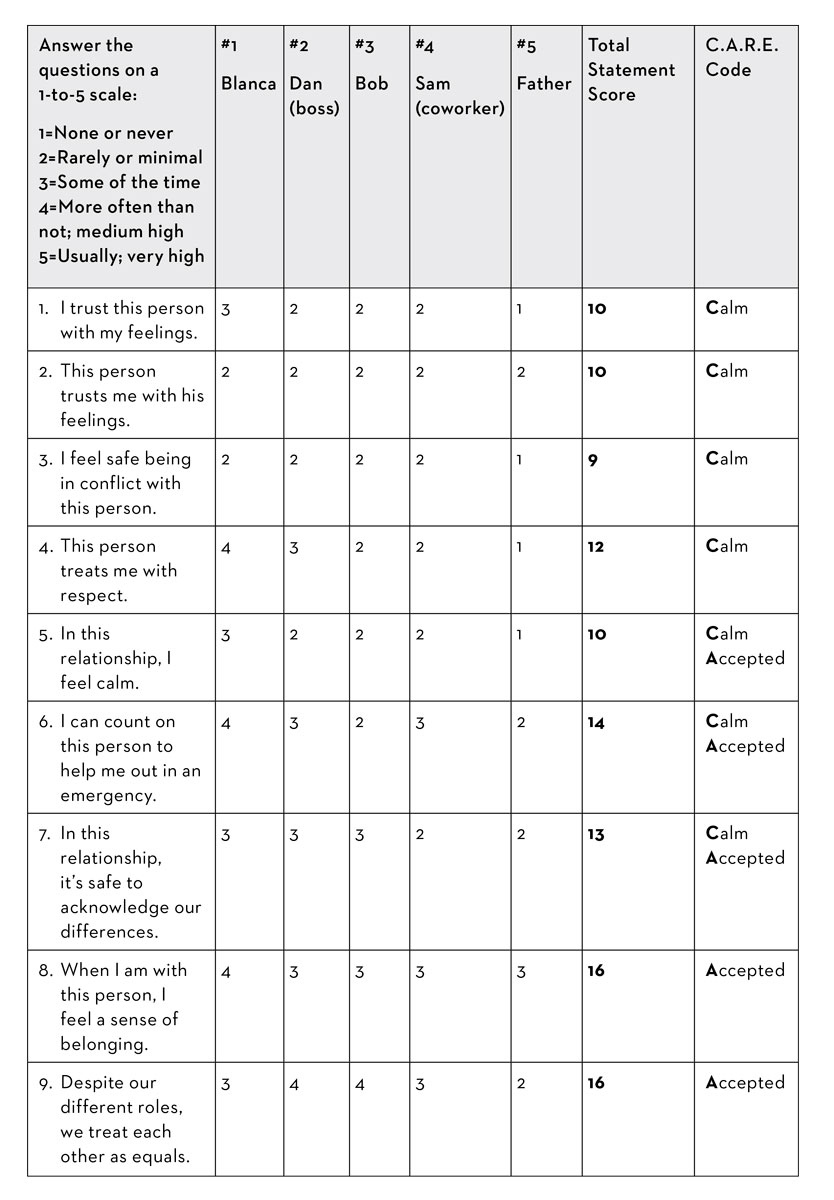

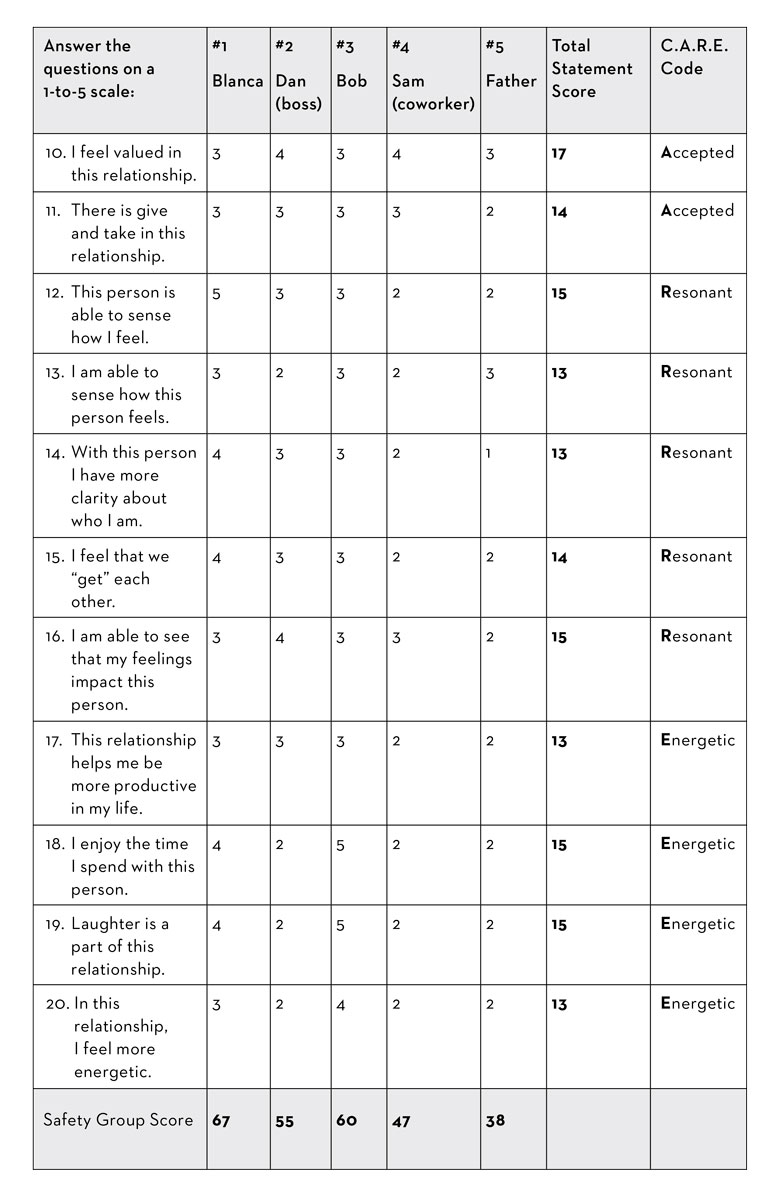

You can see Juan’s C.A.R.E. assessment on the following pages. Below, we’ll look at how the different relational safety groups relate to the Calm pathway. We’ll also see how Juan’s safety groups shaped up.

Relational Safety Groups and the Calm Pathway

There are some patterns that tend to appear in people with weak Calm pathways, and some of these can be described within the three relational safety groups:

High safety (75-100 points): Low vagal tone means that it’s hard for you to feel safe around other people. Given that Juan showed the classic signs of low vagal tone (irritability, anxiety, anger), it’s not surprising that he had no relationships that helped him feel safe.

Moderate safety (60-74 points): If you have a weak Calm pathway, your closest relationships might be found here, in the moderately safe group. This may reflect a fear of trusting people, or it might mean that you don’t have anyone in your life right now who is truly safe. I thought it was pretty good news, actually, that both Juan’s sister, Blanca, and his friend Bob scored between 60 and 75 points, meaning that they felt at least somewhat safe to him. It was likely that as Juan learned skills to manage his overactive sympathetic nervous system, those relationships would improve. In turn, having safer and more rewarding relationships would help strengthen Juan’s vagal tone.

Low safety (less than 60 points): Three of the relationships that took up major time and space in Juan’s life scored below 60. These were relationships that were making his life worse, not better, because they exercised his sympathetic nervous system so frequently. Two of these people were from the office: his boss and a coworker. When they were around, Juan felt out of sync, as if everyone expected him to be as sociable as they were. This feeling of not quite measuring up could leave him irritated and then enraged. It didn’t matter that when Juan described these guys to me, they actually sounded pretty friendly; his weak smart vagus kept him from feeling safe in these relationships. I didn’t think Juan benefited from having his stress pathways constantly stimulated. But I wondered if, eventually, there would be potential for these work relationships to improve.

Juan’s father was a different story. Juan’s father had given up drinking years ago, but he was still a harsh and critical man. Though Juan was no longer an abused child, this relationship continued to weaken his Calm pathway and build up his sympathetic nervous system. This situation had to change.

Juan’s C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

Irritable … or Introverted?

Don’t confuse irritability with introversion. Introversion is a normal, inborn personality trait. Introverts tend to be quieter and more reserved than extroverts. Being quiet and solitary is crucial for introverts, because it helps them feel refreshed. But introverts with healthy nervous systems definitely enjoy relationships. It’s just that they prefer to be with a few close friends rather than go out with a big group of casual friends to a loud party. Their intimate friendships give their C.A.R.E. pathways plenty of stimulation and help them stay in good relational shape.

Introverts may be sensitive, and they’re not at their best during large gatherings. But as a general rule, person-to-person interactions aren’t likely to make them anxious and angry. They aren’t exhausted by having to talk to a cashier at the convenience store. They can listen to a coworker’s request without blowing a fuse. Whether you’re an introvert or an outgoing extrovert, feeling irritable, anxious, and angry in your relationships is a sign that something is wrong—possibly that you’re suffering from poor vagal tone.

Understanding Your Own Calm Score

Add up your scores for the statements whose C.A.R.E. Code includes the word “Calm.” (That’s statements 1 through 7.) Here’s what the total number tells you:

When your C score is between 135 and 175: You’ve got healthy vagal tone, which means your Calm pathway is strong. Your smart vagus is robust and networked into neural pathways that can recall plenty of calming faces and voices; it’s experienced at detecting when new people are friendly and when they’re not. When you’re around supportive people, your smart vagus transmits a calming message to your sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Being around your close friends helps you wind down and relax.

When your Calm score is between 100 and 134: Your close relationships don’t always help you feel relaxed and comfortable. There can be a few reasons for this. One is that the people you spend most of your time with aren’t trustworthy. The other is that your smart vagus isn’t as strong as it could be, which means that even when you’re with people you trust, your brain doesn’t get the message to relax. Actually, both these reasons could come into play, because when you spend lots of time with people you can’t trust, your smart vagus doesn’t get exercised as frequently. As a result, your vagal tone gets weaker. A look at your relational safety groups can help you figure out whether you’re spending too much time in low-safety relationships.

When your Calm score is lower than 100: Any Calm score below 100 is a low number. This is where Juan’s score fell. The scores for all four of Juan’s pathways were on the low side, but at 78, his Calm score stuck out. Given his chronic irritability and abusive upbringing, this was not a surprise. It wouldn’t have made sense for his smart vagus to have good tone, because his smart vagus pathway was shaping itself at a time when his world was the opposite of safe and trustworthy. A very low Calm score usually describes a person who feels hyperalert and jumpy around people, and that fit my impression of Juan.

A low Calm score is a bad news/good news situation. Of course it’s bad news that it’s so hard to be around people—but you probably already know that you’ve been suffering. The good news is that a few therapies can help you feel a lot better, quickly.

Most people with low Calm scores have very few relationships that feel safe. Some have no safe relationships at all. There may be people on your list who are emotionally abusive (like Juan’s father) or physically dangerous. There may also be others who are quite decent—it’s just that you may be unable to pick up the messages of safety that their expressions and words are sending. As your reactive stress responses settles down, some of those relationships may feel more rewarding.

Strengthen Your Calm Pathway: Ways to Feel Calmer and Less Stressed

For everyone with a weak Calm pathway, the first step in feeling better is education. Juan in particular was not used to thinking about his feelings and reactions to the world. When I asked him about friends and romantic relationships, he shrugged the question off by saying the words I hear so often: “I’m not good at relationships.” He, like so many other people, believed he had been born like this.

Of course, he hadn’t been born “like this”—he was born with the reflexes to connect with people, but he needed healthier relationships to build flourishing neural pathways for connection. Using a computer metaphor, I talked with him about the neural pathways for connection that are downloaded into each of us at birth. He was interested in this idea and became engaged in the neuroscience—a very good sign. We talked about how his nervous system had been formed in an environment of both traumatic loss (his mother’s death) and constant threat (his father’s emotional and physical violence). His neural pathways for healthy connection had not been stimulated enough to grow well. It was clear to both of us that until we could turn the volume down on his overactive sympathetic nervous system, he could not move out of the deep isolation he felt. In a self-protective move born out of experience, his brain was telling him to be angry and scared.

For anyone struggling with chronic irritability and anxiety, learning to feel calmer and more trusting means strengthening your smart vagus so that it can tell your sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems when it’s okay to calm down.

You can improve vagal tone by working on one, two, or three of these goals:

1. Starve some of the pathways to your sympathetic nervous system. An overactive sympathetic nervous system hogs all the stimulation, leaving the smart vagus with fewer opportunities to develop.

2. Strengthen the smart vagus directly.

3. If necessary, reduce stimulation to the parasympathetic nervous system. In rare cases, people equate social interaction with life-threatening danger, and the parasympathetic nervous system tells the body to shut down and play dead.

Ready for some ideas? You’ll find plenty, below.

Ways to Starve Your Sympathetic Nervous System Stress Pathways

Many of us suffer from overdeveloped stress pathways. This can be the result of trauma, but it doesn’t have to be. An overactive stress response is a byproduct of our culture. From our earliest days, we’re taught to be independent above all else, and that the only safe place in the world is at the top of the heap, with the competition crushed at the bottom. This is the perfect environment for activating your stress system. By the time we’re adults, most of us have spent two decades building up our sympathetic nervous system and ignoring smart vagus skills, like learning to soak up the calming effects of a trustworthy relationship. Adulthood brings a whole new bucket of stresses: paying the rent or mortgage, surviving life in the cubicle, raising children … not to mention worrying about terrorist bombings or anthrax in the mail. If you’re living a typically hectic contemporary life with little time for relaxation and play, you probably feel chronically stressed. You’re not sick, though, not any more than Juan was. Like him, you’re having a normal response to a cold world.

And there was no doubt that Juan suffered from an overactive sympathetic nervous system. In fact, his sympathetic nervous system was stuck in the On position; he practically lived in fight-or-flight mode. That’s one reason he was so prickly. Lots of people who frequently feel anxious are living with a noisy sympathetic nervous system.

If you feel so chronically tense that, like Juan, you are revved up and worn down, your most important job is to reduce how often your sympathetic nervous system kicks in. Remember the first rule of brain change: Use it or lose it. Use your sympathetic nervous system’s stress pathways often enough and they bulk up. To reduce chronic jumpiness, you need to weaken those stress pathways by starving them of stimulation. Here’s how to do it.

Reduce Exposure to Unsafe Relationships

Take a look at your relational safety groups. If there are any in the lowest safety range, examine these relationships more closely. Are you being physically or emotionally damaged by any of them? The first step to starving the sympathetic nervous system stress pathways is to end or reduce contact with people who are dangerous, who give your alarm system a very good reason to start ringing.

In Juan’s case, this meant cutting back on time he spent with his father. I didn’t think Juan needed to cut off the relationship completely, but together we decided that he could reduce the number and length of his visits. When Juan did see his father, he could bring Blanca along; he felt safer in her presence (that safe feeling was good for his smart vagus), and he wondered if maybe they could help each other by coming up with a plan to leave if their father turned nasty.

When a relationship is very stressful, it’s not always easy to know what to do.

You should always, always, always leave a relationship that is physically or sexually abusive. If you are in a relationship that is emotionally disrespectful, the decision to leave can be weighed against the level of harm, the importance of the relationship to you, and whether you have other safe relationships to balance the emotional destruction. If the person who feels emotionally unsafe is a parent, the choice to leave can be extremely painful. You’re biologically wired to connect with your parents. Cutting off a relationship with either one is like cutting off a leg: something you’d do to save your life, but only when there are no other options.

When staying is painful but leaving is too brutal, I suggest a couple of alternative approaches. Recruit a supportive mental health professional to help you with these. The first is to reduce your exposure to the emotionally unsafe person. Cut as far back as you can on the time you spend with him or her in person, on the phone, or online. Work with your therapist or counselor to help you identify how, when, and why you interact with this person. Those interactions are probably based mostly on the unsafe person’s needs, but with some good help you may be able to change those terms. You can also start noticing when the unsafe person is getting worked up—and at that point you can end the exchange. As you get clearer about the ways that a person is being demeaning, and as you build other, safer relationships, you will be able to see the behavior and the damage it causes more clearly. This insight will help you make decisions that you can live with, including a decision to spend even less time with the person or, perhaps, to finally end the relationship.

While you’re working to reduce your exposure to difficult relationships, you should also increase the amount of time you spend in your safest relationships. Every minute you spend with your most trusted friends helps heal the neural pathways that are being damaged by the low-safety relationship.

Consider Medication to Quiet the Stress Response

Aside from getting out of high-alarm situations, a smart move for calming an overactive sympathetic nervous system is to consider medication. Not everyone needs this step. But as Juan and I talked about how hard it was for him to sit still, he explained that he had once tried meditation. When he sat quietly for even a few minutes, his mind would spin, filled with traumatic images he could barely identify or remember. At this point, it was clear that he needed stronger help. He started fluoxetine, which is a serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant, or SSRI. This class of drugs increases the availability of serotonin in the brain. You’ll need to work with a doctor to get an antidepressant, obviously, and you should be aware that antidepressants come in different categories. Some, like bupropion (the brand name is Wellbutrin), can actually stimulate your sympathetic nervous system—which is counterproductive. I chose fluoxetine for Juan because not only does it treat symptoms of depression, it also buffers the stress response systems.

It can take between two weeks and two months for an antidepressant to start working, but when the effects did take hold in Juan’s brain, they were very helpful. Juan felt a quieting in his body that he had never known—it felt like he finally had access to the ability to pause and reflect on his behavior. Juan reported that the effect was good but also so new that it was slightly unnerving. Now that he was a little less reactive, he could also sit still and even meditate—at first for just two five-minute periods each week, and then for fifteen-minute sessions four or five times weekly. When I saw him, he was visibly less jittery, and he looked less worn out. It was too soon to tell how long Juan would need to stay on antidepressants. Some people take them as a short-term strategy, sometimes for only six to twelve months; others need them for the long haul. No matter what, Juan had accomplished the first task: soothing his chronically overactive sympathetic nervous system.

Defuse Yourself Before You Blow Up

Do you tend to explode in anger? Many people with low vagal tone are on a short fuse. Juan frequently blew up at coworkers, girlfriends … anyone who happened to be in his sights when he felt stressed. But some people are like the husband of one of my clients: when he’s frustrated, he loses his temper with himself. He doesn’t lash out at his wife or anyone else, but his self-criticism is so vitriolic that it negatively affects everyone in the house.

Try monitoring your level of agitation on a scale of one to ten, with ten being a full-scale screaming, venting tantrum. The idea is to pull yourself out of a seriously irritating situation before it’s too late. If you find yourself reaching a five, excuse yourself from the interaction. Leave the room if you can.

By keeping yourself from going over the edge, you decrease how many times your sympathetic nervous system goes into full-out war mode. Eventually, it will become less irritable and less likely to sound the alarm at relatively small problems. And, of course, the less you snap at people, the safer they will feel around you.

Relabel and Refocus

When your sympathetic nervous system is overactive, you feel more stress than other people. This leads to even more stress! Here’s a way to step in and break the cycle. When you feel overwhelmed by stress, try the “relabel and refocus” approach. This method was created by Jeffrey Schwartz, a psychiatrist at UCLA who specializes in neuroplasticity, especially as it applies to obsessive-compulsive disorder (another problem with roots in neural pathways that have wired together and become strong from consistent use).1

First, for the “relabel” part, pause and take ten deep breaths. Stress causes us to take short, quick breaths, which reduce the oxygen levels in the brain. With less oxygen, brain cells can’t work as well, and your brain becomes more irritable, which worsens the stressed feeling. So take those breaths—and then relabel your body’s stress reaction. Instead of saying to yourself, I can’t take this! or My girlfriend is driving me crazy! say, This feeling is just my overactive sympathetic nervous system sending me a wrong message. This relabeling can feel stiff at first, or even ridiculous, but it helps you separate yourself from the experience of stress. This allows the cognitive part of your brain to come online and begin to modulate the agitation.

Then “refocus” your attention. Move it away from whatever is driving you nuts and think about something different, something that’s pleasing. This is what Sally, the woman who lied to her boyfriend, did when she purposefully moved her thoughts away from how exciting it would be to tell a lie and on to how good she felt when she and her boyfriend were getting along on honest terms.

A particularly powerful kind of refocusing is what I call a PRM: a positive relational moment. A PRM is a time you remember feeling safe and happy in another person’s presence. For me, a favorite PRM is the time I was walking with my then-thirteen-year-old twins toward Old Faithful at Yellowstone National Park. It’s a gorgeous day and we’re heading down the path, with me in the middle and each child holding one of my hands. Thirteen-year-old kids, willing to hold hands with their mother! When I bring this PRM into my mind, I always smile, and my smart vagus helps me feel less stressed. I also feel a fullness in my chest—it’s like I’m brimming up with happiness—thanks to a little hit of relational dopamine. When I’m up against a stressful work deadline or stuck in Boston traffic, I think of this PRM. I know that instantly I’m activating healthy neural pathways and shrinking the ones that cause unnecessary stress.

(Of course, if you’re stressed because you’re in real danger, don’t bother with relabeling and refocusing. Go ahead and let the stress response do its work—and escape, fight back, call 911, or do whatever you need to do.)

Relabel and refocus takes advantage of all three rules of brain change. First is the Use it or lose it rule. When you can lift your mind out of its stress, you use the stress response less; eventually you will begin to lose it. (Well, you’ll lose its overactive, unnecessary aspects.) And there’s the second rule: Neurons that fire together, wire together. When you are consistently overwhelmed by stress in particular situations, the neural pathways for stress link up with the neural pathways that pick up the sights, sounds, and other sensations of those situations. If you can keep these neurons from firing at the same times, they won’t wire together as tightly. Finally, this exercise takes advantage of the third rule of brain change: Repetition, repetition, dopamine. You’ll have to repeat the exercise to see results, but those results will happen faster if you add in the power of dopamine. By thinking of something positive, the way Sally did when she thought about genuinely intimate moments, you’ll stimulate dopamine and help melt away the unwanted neural pathways. When you use a PRM, you’re getting dopamine in an even bigger way, because a PRM generates dopamine from healthy relationships.

Try a Neurofeedback App

I’ve referred people with jittery sympathetic nervous systems to neurofeedback for years, but I didn’t really understand the dramatic difference it can make in a person’s life and relationships until a member of my own family decided to try it.

Ben was a highly competent man, admired by friends and colleagues for his keen intellect and easy way with people. However, his family and friends—and especially his partner, Aaron, knew him to be riddled with worry. Ben’s sympathetic nervous system would fire, making him think that something dangerous was happening. He began to compile a mental list of dangerous things that could happen or that have happened—and the next time his body alarm went off, the items from the list popped into his head, and he immediately had ten things to worry about. Nighttime was a silent hell for Ben; he’d wake up with his heart pounding and his mind grabbing on to the nearest negative thought as an explanation. Unfortunately, every once in a while, something bad did happen, which was just the intermittent reinforcement his body needed to convince itself to remain on high alert all the time.

Aaron had mostly grown accustomed to the way Ben’s anxiety could hijack their lives. When they traveled, he knew to expect an extra fifteen minutes before they left a hotel room, because Ben obsessively double- and triple-checked under the beds and in the drawers for forgotten items. Aaron barely registered the way Ben followed the weather forecast before a trip and constantly predicted that an impending storm would prevent their departure. Most days, Aaron could also screen out Ben’s repeated attempts to feel safe and in control of his emotions. At least once a week, however, Ben’s anxiety would surge unpredictably—and it seemed to suck the air out of the room. Aaron felt himself “catching” the feeling. As Ben panicked, Aaron could feel his own chest tighten and his breath become shallow. In those moments, the only way for him to manage was to leave for an hour or so to clear his thoughts and feelings. Ben understood Aaron’s reaction cognitively, but each time Aaron walked away, Ben felt abandoned and judged. This chronic anxiety put them both in a no-win situation and undermined the relationship.

After his first neurofeedback treatment, Ben noticed a bounce in his step, and the rest of us, including Aaron, noticed that he was more communicative. After two weeks, his nighttime worrying had stopped, and even the daytime fears had greatly subsided. He radiated a brighter energy—and now Aaron “caught” this better mood instead of Ben’s anxiety. The impact was so profound that he and Aaron decided to rent a neurofeedback unit so Ben could hook himself up throughout the week.

Neurofeedback takes advantage of the rules of brain change to rewire the brain.

Your central nervous system communicates by electrical current; individual brain cells send messages throughout your brain and body by electrochemical reactions. With a highly sensitive meter, the amount of electrical current sent through your brain cells can be measured and monitored. In an EEG, electrodes are placed on your scalp to produce a general picture of the electrical current running through your entire brain. The electrical signals emanating from your brain will vary, depending on where you are picking up the signals, and the frequency of current is divided into categories based on the wavelength and amplitude. It’s the healthy integration of all the different kinds of brain waves that creates a sense of equilibrium or peace. For example, if you have too many alpha waves in the frontal part of your brain, you may find that attention is difficult. If you are having lots of anxiety, you may need to increase both alpha and alpha-theta waves.

Neurofeedback uses a reward system to help you pull your brain waves back into balance. What is so remarkable about this modality is that it bypasses cognition: you can’t just think your way through a session. I was once hooked up to a neurofeedback machine at a conference in Texas many years before it became more popular. Electrodes were placed on my head in three locations, and at the other end they were hooked up to a computer system. On the computer screen was a game that looked like a simpler version of Pacman, one of my favorite old video games. When the electrical current in my brain gave off the desired brain waves, the Pacman unit began to munch up little dots. When my brain wandered off to another frequency, the munching slowed down. Miraculously, my brain knew that it should try to stay in the frequency that provided the dopamine-producing “reward” of the Pacman munching. After just a few moments, the munching was steady, the desired pathway was activated repeatedly, gaining strength and recruiting other neurons into its bulk. Neurofeedback is now more sophisticated, with dopamine rewards that appeal to a wider audience, such as watching a favorite DVD. When your brain waves are in the desired range, the video plays, and when they drift out of the desired range, the video fades out.

You can receive neurofeedback at a therapist or doctor’s office, or, like Ben, you can rent a neurofeedback machine for your home. (If you rent a home device, you’ll still need to work with a clinician to determine the appropriate settings, both at the beginning and as your brain changes over time.) But there’s also an app for that: Xwave makes a headset plus app that you can use via your phone. The headset has only two settings: one that helps you grow the beta waves necessary for focused attention, and one for the alpha waves that you need to relax. The headset is a less sophisticated option than a full neurofeedback machine, but it can be useful if you want to focus on either of these two issues. Jennifer, the woman who felt a constant agitated buzz in her body, bought the Xwave app and headset to decrease her sympathetic activation. She often used it for fifteen minutes of relaxation at lunchtime—a smart scheduling decision in an office full of low-safety relationships.

More Ways to Treat Chronic Tension, Irritability, and Jumpiness

Sometimes doing psychological work is hard. But teaching your nervous system to calm down can be like a day at a spa—wonderfully indulgent and relaxing. Even if these strategies drive you crazy at first (for example, you might find it hard to be still), keep with them. You will come to love what they do for you. Jennifer, for example, downloaded a relaxation CD. By following the soothing voice at night, she was able to focus on each part of her body, first consciously tensing and then releasing it. By the end of the CD, she was usually asleep.

Here are nine soothing suggestions for managing a jumpy sympathetic nervous system:

1. Increase the time you spend with people who feel safe to you.

2. Work out. Moderate to intense cardiovascular exercise is best.

3. Use a relaxation CD. Some good choices include Dr. Alice D. Domar’s Breathe: Managing Stress and Rod Stryker’s Relax into Greatness.

4. Try the Emotional Freedom Technique. My clients report that EFT has a seemingly magical ability to reduce the intensity of an overwhelming emotional state. EFT works by tapping gently on the endpoints of meridians (in Eastern medicine, meridians are your body’s energy pathways) as you focus on the emotion that’s been troubling you. For more information, visit the website www.emofree.com.

5. Meditate.

6. Play with a pet.

7. Take a hot bath.

8. Get a massage.

9. Ask a safe person for a cuddle or a hug.

Choose the ones that sound most appealing and see what happens. If you don’t notice a difference after a few weeks, try a different set. Don’t let these treatments go to the bottom of your daily to-do list just because they feel great. They’re also vitally important to the health of your Calm pathway.

Strengthen Your Smart Vagus

Once you’ve calmed your stress pathways and you feel a little less reactive, you can start building up your smart vagus pathways. The benefit: you’ll develop a better sense of when to trust people and enjoy them, and your brain will be able to send “relax” messages to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

Exchange Short Smiles

If you don’t give your smart vagus regular exercise by exchanging caring expressions with people, it weakens. To help the smart vagus bulk up, trade short smiles with the people you like best. Not a huge fake grin, just a garden-variety smile that communicates a quick and friendly hello. Look the other person in the eye, and make an effort to notice the facial expression the other person delivers in return.

This exercise seemed like a perfect fit for Juan, who often avoided eye contact. When he did look at people directly, he often misinterpreted their expressions. A smile seemed like a smirk; a laugh might come across as sarcastic. In fact, when Juan and I went over what had happened when he blew up during the meeting, we pieced together the possibility that the junior colleague hadn’t been trying to take Juan down a notch. He may have been more like a puppy, eager to share his ideas.

My instructions to Juan were simple: when you’re interacting with someone, look at his or her face. Notice if the person is smiling or engaged in the conversation, and if they are, smile back and note what that feels like. This step meant that not only would Juan need to register the expression on the face of the other person, he would also begin to be mindful of the ways his brain and body immediately filtered facial expressions through his most prominent relational template—the one he had with his father. In that template, there was no kindness or respect. Juan could make a quick mental note that the person he was interacting with was not his father and that the smile was probably one of engagement, not rejection. This very basic process would activate his smart vagus and eventually improve its tone.

Juan began doing this with just Blanca and Bob, his safest relationships, but soon he moved on to his coworkers, too. Juan was surprised to find that exchanging a quick smile with colleagues gave him a momentary lift. Before long, he was able to hold longer conversations with people at work, and we moved our focus to helping him actively listen to their words. Engaging in facial communication and in active listening made him feel different—less alone and even a little calmer. This happened partly because he was enjoying the interaction, but it was also because he was, little by little, rewiring his autonomic nervous system.

In a workshop I did with a group of teenagers from the Bronx last year, we all took out our smartphones and looked at photos of smiling friends. I asked everyone to pay attention to what they were feeling in their bodies, and every single person reported feeling calmer, happier, or less stressed. It’s amazing that such a quick relational intervention makes an immediately noticeable difference. So build a photo gallery on your desk or phone, with pictures of your safest people looking happy or goofy. Make a point of looking at them a few times each day to buff up your smart vagus and to feel better.

This is one of those exercises that can sound incredibly silly—if you have been told all your life that other people are judgmental, frightening, and competitive with you. Try it anyway. This is neuroscience, people; our brains are wired to work better when our faces engage and connect with the faces of others.

Listen Yourself into Safety

When a soothing sound wave enters your inner ear, the vibrations move the bones and muscles, and the smart vagus fires, helping you feel less stressed. So one way to grow the smart vagus is to listen to the voice of someone you love. You can also listen to music that reminds you of being with that person. (No breakup songs allowed!) The more you stimulate the smart vagus, the stronger it will get.

Another way to stimulate the smart vagus is to actively listen to another person. The next time you’re feeling anxious in a social situation, use this technique:

First, scan your body and determine your stress level. If you pick up on a lot of stress, remind yourself not to talk mindlessly, space out, or walk away. Those are all stress reactions. Instead, try actively listening to a specific conversation.

In power-over cultures like ours, inserting your point of view into a conversation is seen as more valuable than listening to others, so it’s normal to feel pressure to talk. But real dialogue means speaking and listening. It is essential to practice and value both skills equally. Take the pressure to speak off yourself, and head into the conversation focused on listening.

However, even when you no longer feel pressure to talk, listening can be hard work, especially when you’re anxious. Your body could be screaming at you to do something, and listening means staying pretty still. It helps to give yourself tasks to focus on, so remind yourself to look at the speaker and mentally repeat her words (just in your head). If you catch yourself preparing what you’ll say next while she’s talking, gently move your mind from your own thoughts and place them back on the speaker. Ask questions, too, but just for clarification. Then run a quick repeat scan of your stress level. You should notice a difference; if not, go back to your active listening.

Ironically, actively listening makes you feel less stressed, and this means you’ll have better access to the thinking part of your brain. When you do speak, you’ll contribute more meaningfully to the conversation. None of us is particularly fluent when we’re anxious.

Relational Mindfulness

Relational mindfulness is a two-person exercise developed by Janet Surrey and Natalie Eldridge, faculty members at the Jean Baker Miller Institute. It is a form of Insight Dialogue Meditation, and it is a powerful way to stimulate your smart vagus nerve by combining relationships with the known calming benefits of meditation.

Most meditation exercises involve sitting alone or in a group, focusing on your breathing and attempting to escort random thoughts out of consciousness. Some types of meditation use mantras or chanting. The goal of these practices is to settle down your sympathetic nervous system by tapping into your parasympathetic nervous system. (Yes, some people have a freeze response caused by the parasympathetic nervous system. But for most of us, stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system in appropriate amounts and at appropriate times simply leads to a calm, centered feeling.) Studies have shown that regular meditation actually changes brain structure and creates more activity in the prefrontal cortex, an area that feeds back to the limbic system, causing you to feel less stressed.

Relational mindfulness uses the same techniques as meditation: breathing and ushering thoughts from the mind. But Jan and Natalie ask people to meditate by sitting across from each another, eyes open.

I bet this sounds overstimulating, and in some cases it can be. There’s some evidence that when people hold eye contact for more than three seconds, they either fight or make love. Either of these activities will disturb your meditation! But glaring, unbroken eye contact is not the point. This is not a stare-me-down contest. A gentle, respectful gaze works much better, and you’re always free to look away and take a break. Sometimes I have people ease into this exercise by practicing a few minutes of compassion meditation, which you can learn about here.

Choose one of your safest friends to invite into a relational mindfulness practice. The first five or ten minutes can produce intense feeling; expect to temporarily Ping-Pong back and forth between activating your smart vagus (and feeling relaxed) and activating your sympathetic nervous system (and feeling like you want to jump up and run away). You may get a case of the giggles, too. But if you stay with it for just ten minutes, the stress of the interaction will give way to a safe sense of being intentionally held deeply and respectfully in a human relationship. The result can be a profound stimulation and reworking of the smart vagus, especially if you practice on a regular basis.

This exercise can be particularly moving and intense if you try it with a romantic partner—but do this only if the relationship is a safe one. Over time, a relational mindfulness practice can help couples bypass their usual squabbles. It also helps create even more safety inside the relationship, because the exercise trains the smart vagus nerves to fire at the sight of a partner’s face. This leads to a calm, balanced feeling.

Starve the “Freeze” Response

People with a supersensitive parasympathetic nervous system feel so threatened by social interactions that they feel like they might die. I’m not exaggerating. Of course, they know they’re not going to die, but their brains don’t. Their brains remember an old equation: people = terror. It reacts by telling the body to shut down. This is different, really different, from the fight-or-flight response. It’s a completely different branch of the nervous system that’s activated. Instead of feeling a rush of adrenaline, you feel numb, quiet, and sleepy. You may not be able to speak if you feel this way. You may instinctively wander away and even feel like curling up into a ball. What you’re experiencing is the human equivalent of playing dead, meant to persuade the threatening person to move away from you. You can’t even talk to anyone to tell them how frightened you are, so people might react to your behavior by raising their voices or stomping around in bewilderment—which only increases your fear.

To recover from the effects of a parasympathetic nervous system response, you’ll have to dig deep. Your body may order you to shut down, but you have to reach a compromise with your instincts. Go ahead and remove yourself from the situation that is scaring you, but try not to lie down or curl up. This is a time when you actually need to stimulate your sympathetic nervous system; studies show that mild to moderate stimulation of your fight-or-flight response can be energizing and focusing. But you need to stimulate it gently, just enough to feel alive and to warm you out of your frozen state. Physical movement is ideal—nothing very strenuous, just a walk, some flowing yoga postures, or even a slow jog.

A parasympathetic nervous system freeze response is a sign that you feel extremely threatened. No matter what the circumstances, if you experience a parasympathetic nervous system freeze response, you need more help and support than you’re getting. Call on your safest friends and find a caring therapist who can help you gently address the source of your fears.

Take the Next Step

A feeling of calm is the cornerstone of a relationship. Without the experience of trusting each other, facing each other respectfully, looking at each other’s facial expressions, finding the words to explain your relational experience, and having the patience and ability to actively listen to the other’s point of view, the relationship can’t feel safe. As you work on your Calm pathway, expect the positive effects to spill over into all your relationships—and into your other pathways for connection.

If you’ve practiced the exercises here and are noticing a change in how you feel around people, that’s wonderful. Before you move on with the program, retake the C.A.R.E. relational assessment. Your scores may be different now, and you can adjust your next steps accordingly. Just don’t stop! You’ve taken some relational hits in your life, but now you can feel even better by working on the next step. If you’re following the program the way I’ve laid it out here, you’ll move on to the Accepted pathway. But—of course—feel free to use whatever part of the program calls out to you. Always, the C.A.R.E. plan is all about you—and your relationships.