Four Ways to Click: Rewire Your Brain for Stronger, More Rewarding Relationships (2015)

Chapter 4

THE C.A.R.E. RELATIONAL ASSESSMENT

Up until now, we’ve talked about the underpinnings of relational neuroscience. Now it’s time to launch that knowledge into practical use. This half of the book is about how to use the C.A.R.E. plan so that both your brain and your relationships are healthier.

Remember, the C.A.R.E. program consists of four parts. Each part represents a neural pathway for connection, and each of those pathways represents an aspect of relationships. When those pathways are up and running smoothly, you feel:

· Calm (via the smart vagus nerve)

· Accepted (thanks to the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex)

· Resonant (mirroring system)

· Energetic (dopamine reward pathway)

The four chapters that follow are full of suggestions and exercises for strengthening each pathway. You’ll get the most benefit if you follow the entire program, but I often mix up the order of the steps to reflect a client’s needs. You can do the same. A few people find that they need to focus on just one or two neural pathways instead of all four, and that’s fine, too.

However, everyone needs to begin with the C.A.R.E. relational assessment, a tool you’ll find in this chapter. Performing this assessment is like putting on 3-D glasses at the movies: it helps you see your relationships and your mind in a fuller dimension. I guarantee you’ll have at least one aha moment in this chapter. Most people have more than one.

The C.A.R.E. relational assessment helps you discover:

· which of your relationships are most actively shaping your brain;

· what kind of neurological shaping is taking place inside you;

· relational patterns that may have been invisible until now;

· how to engage the C.A.R.E. plan so that you can get right to work on the neural pathways that need the most healing.

As you work on the assessment, expect insight. Expect a little discomfort; that’s normal whenever you take time for honest reflection. Most of all, expect to finish this chapter with a plan for a more connected, more satisfying set of relationships. The work begins right here.

If You Skipped the Science Chapters …

You’re fine. I happen to love the science behind relationships, but if that’s just not your thing, you can begin here. Inside this chapter you’ll find everything you need to know to get going, including bite-sized summaries of the four neural pathways that form the foundation for the C.A.R.E. plan.

How to Perform Your Relational Assessment

Do this exercise when you have about fifteen to twenty minutes of uninterrupted quiet time. It involves these five steps, which I’ll describe in more detail on the following pages:

Step One: Identify your brain-shaping relationships

Step Two: Complete the C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

Step Three: Sort your relationships into safety groups

Step Four: Evaluate your C.A.R.E. pathways

Step Five: Optimize the C.A.R.E. program

Step One: Identify Your Brain-Shaping Relationships

Relationships shape your neural pathways, so let’s figure out which ones are doing most of the relational shaping inside your brain. Later, you’ll see how they are shaping it.

When I began using relational assessments, I would tell people to perform the assessment based on the most important relationships in their lives. Then I realized that when we think of the people who are most important to us, it’s instinct to pick out just one or two of the highest-quality relationships. Yet those relationships aren’t necessarily the ones that have the most effect on us. In reality, most people have a much wider network of acquaintances who leave a mark on their relational templates. And the more time you spend with someone—no matter whether the relationship is good, bad, strained, or workaday—the more it shapes your brain.

To get a more complete idea of the relationships that affect you, make a list of the adults you spend the most time with. By “time,” I mean two things. One is face time: the people you see most often during the week. These can include friends and family, but don’t be surprised if the names that pop up are people you may not feel all that close to: coworkers, neighbors, carpool partners, parents of your kids’ friends, and the acquaintances you’re always running into at the hardware store. I also want you to list the people who take up your mental time. These are the people who, for good or bad, are under your skin. You spend time thinking about them, worrying about them, writing loving e-mails to them, or feeling annoyed with them. Don’t make the mistake of writing down only the names of the people you like the best!

Everyone is different when it comes to relationships, so don’t worry about how many people are on your list. For instance, I am a person with many acquaintances but only a few very close friends. Some would call me an introvert. When I did this exercise, my list had seven people on it. In contrast, my best friend could easily jot down more names than I have items on my weekly grocery list. He has so many people in his world that a really complete list would take multiple sheets of paper. He is an extrovert for sure.

Now put those names in order of how much total time—whether it’s face time or mental time—you spend with that person. The person you spend the most time with should be at the top of the list; the person you have the least contact with should be at the bottom. Put stars by the first five people on the list. These are the relationships that most dramatically influence your brain.

This exercise is already pretty interesting, isn’t it?

Turn to the relational assessment chart here. Now take the five starred names and, going from the first to the fifth, write in the name of each person across the top of the chart in the spaces provided.

A note: people who have been traumatized in their relationships often equate human interaction with pain. They may be so terrified of other people—or so turned off by them—that they see no alternative to their isolation. If this sounds like you and you are not able to think of any current relationships, think about relationships in the past that have been important to you, or about a pet that you have been able to love and trust. Remember, one goal of this program is for you to learn skills that will gently and safely expand your relational world. As long as you have a brain, you can change and connect.

Why Aren’t Children on the Relational Assessment Chart?

Relationships with children are important. But healthy adults don’t depend on children for their emotional needs, so kids don’t appear on the relational chart. If you spend most of your time with children, you need to be sure that you have time and contact with supportive adults. This is doubly true for parents who are in a difficult relationship with a child—for example, a teen going through a turbulent adolescence—because the stress can and will impact your brain.

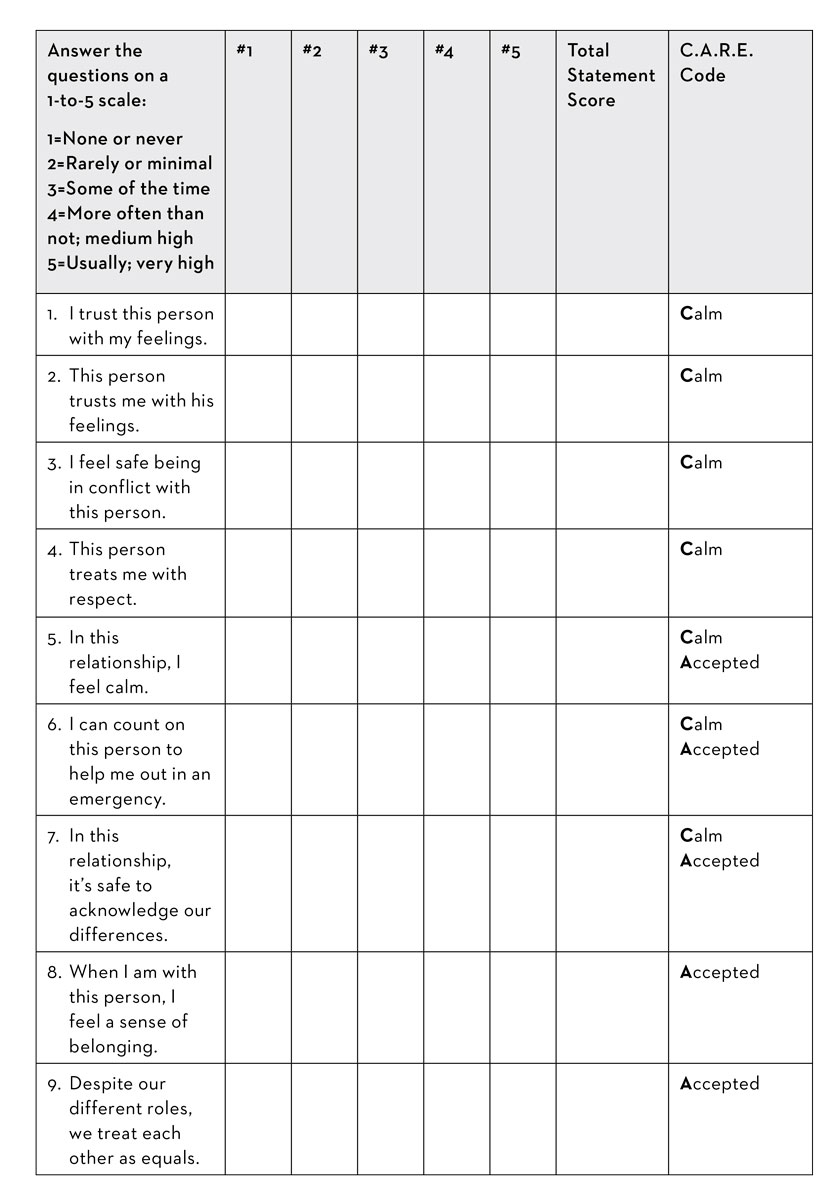

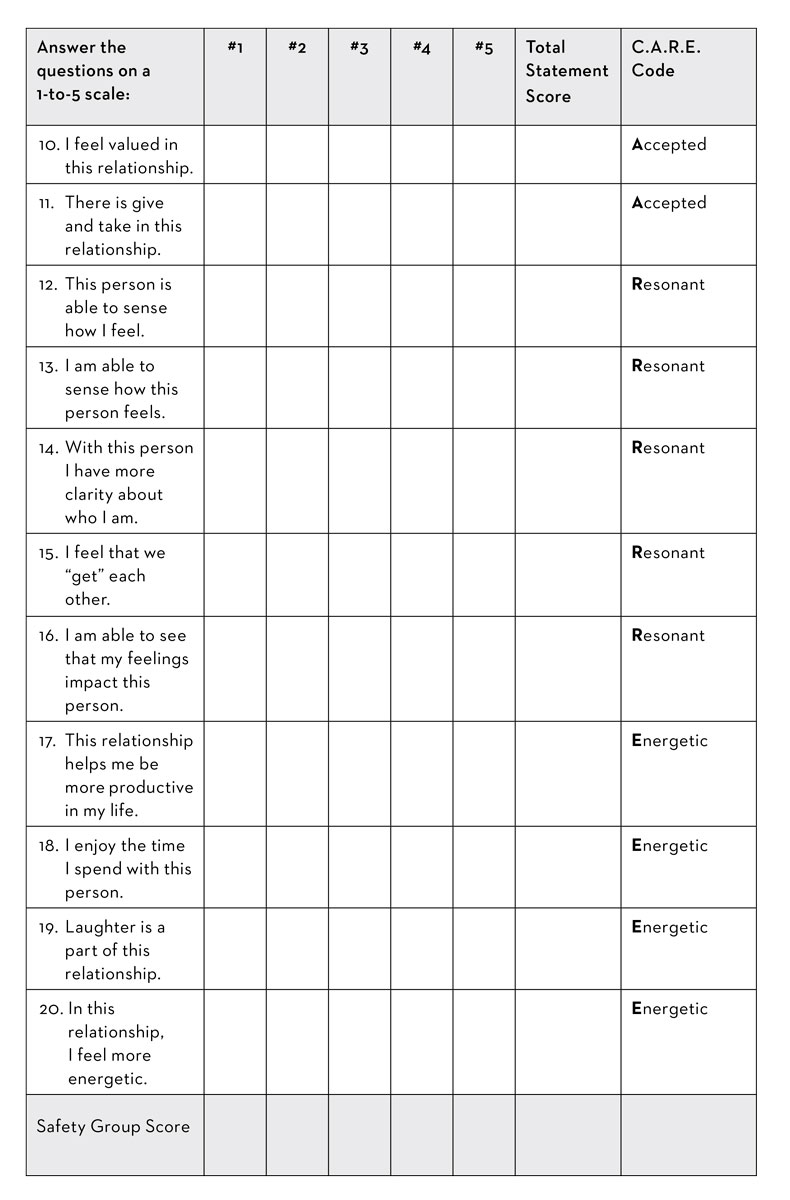

Step Two: Complete the C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

The C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart makes twenty statements about relationships. For each of the five relationships you’ve written across the top, evaluate how frequently each of these statements is true, using this 1-to-5 scale:

1 = none or never

2 = rarely or minimal

3 = some of the time

4 = more often than not; medium high

5 = usually; very high

Try not to overthink this process; go with your gut. If you are struggling to come up with an accurate response to some of the statements, you can “try on” the relationship. Here’s how: recall a recent interaction with the person, or create a mental image of a typical exchange between the two of you. Pay attention not just to the narrative that emerges in your mind but also to the feelings that arise in your body. Each relationship is coded within you as a complex mind/body image; that’s why you have to listen to your body (in some cases, this is your gut in a literal sense) as well as to your brain when you are deciding how to rank each statement.

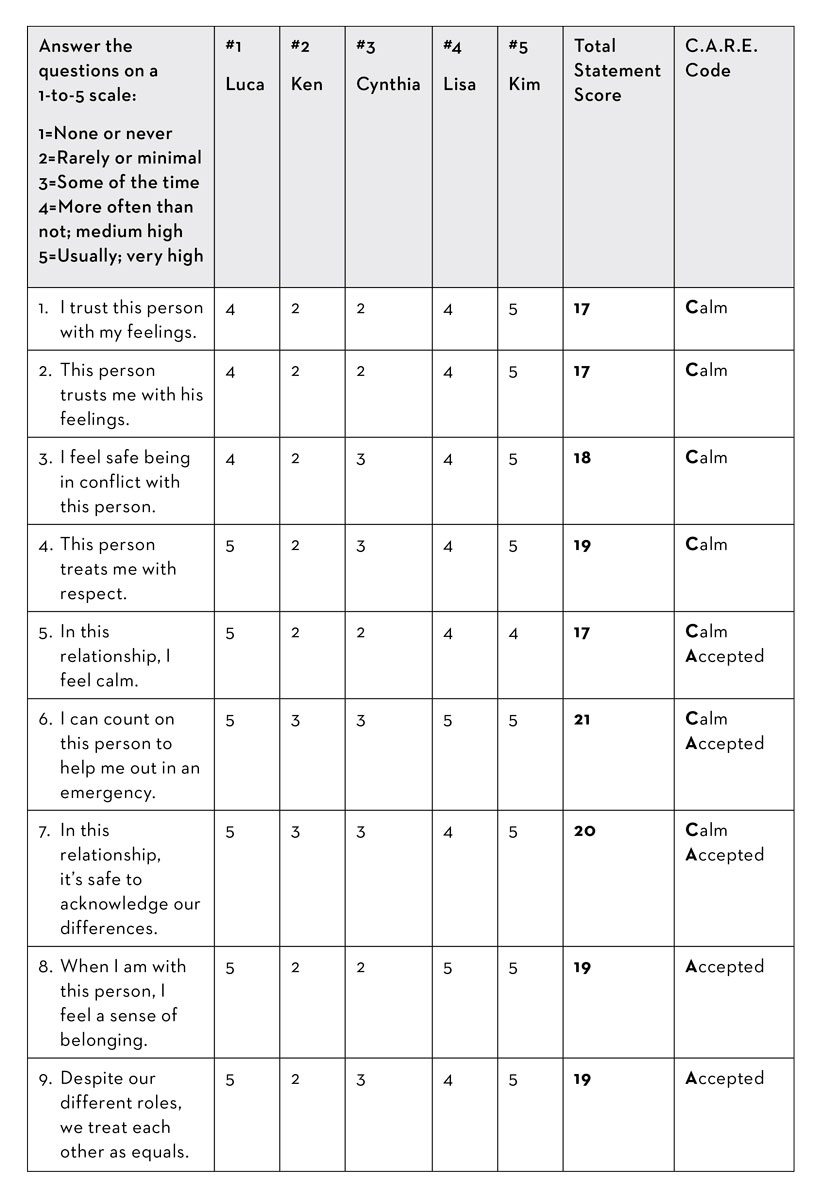

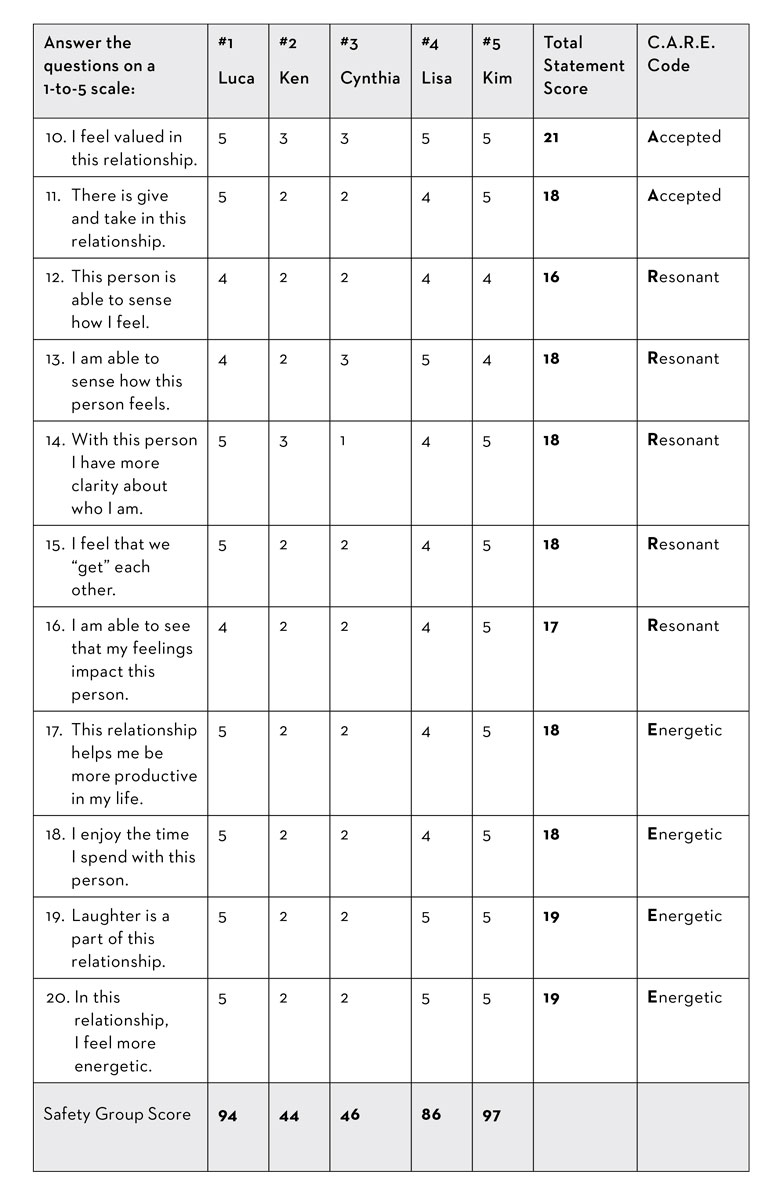

The C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

In a moment, I’ll give you some tools for analyzing the chart. Most people, though, find that they have some immediate reactions, even before they do any kind of analysis. Take a minute to think about your own reactions now. Do you notice any patterns? Surprises?

The chart is a representation of the relationships that literally shape your brain. Remember the second rule of brain change:

Neurons that fire together, wire together.

This means that the more time you spend in a relationship, regardless of whether it is mutual or abusive, the more that relationship is actively shaping your central nervous system. Do you spend lots of time in relationships that you ranked with ones and twos? Your brain may be shifting to a state of chronic disconnection to protect you from the pain. On the other hand, if you spend most of your time in relationships marked by fours and fives, then your connected brain—your smart vagus nerve, your dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, your mirroring system, and your dopamine reward pathway—is being programmed to expect healthy relationships and to thrive in them. You are supporting your capacity to find joy and comfort in the context of the human community.

If your relationships score mostly in the low numbers, does this mean that you are bad at relationships? Absolutely not. Everyone spends some time in difficult relationships, and sometimes we are thrown into them through no choice of our own. Your challenge is to learn which relationships can be grown so that they are stronger and more supportive, and which ones you may eventually need to put aside. You’ll also make it possible to create rewarding new relationships. Finally, you can learn how to inoculate yourself against very stressful relationships, such as those at work, that you may not be able to leave and cannot change.

At this point, don’t write off any of your relationships unless you are clearly being abused. Instead, read on. You’ll use the assessment to determine which steps of the C.A.R.E. program to use first. The C.A.R.E. program can help you lay down the neural circuitry that makes it easier to have growth-fostering relationships. Here’s to a relational world ranked four and above.

Step Three: Sort Your Relationships into Safety Groups

As you go through the C.A.R.E. program, you’ll perform exercises that are designed to improve your neural pathways for connection. You can do many of these on your own, but some of them ask you to practice new methods of interaction with another person. I promise that I won’t ask you to try anything that feels too bizarre or too frightening; I firmly believe that baby steps are the best way to get where you want to go. But even when the steps are small, relationship changes make most of us feel uncomfortably vulnerable. Why? One reason is that most of us are wired to fear difference and change. Another is that our culture makes it really hard to be vulnerable; it doesn’t teach the skills that can make relational change easier on everyone.

You can improve your chances of having a good experience with change if you take these small risks within relationships that are already fairly sturdy and flexible. Here, you’ll sort your relationships into safety groups so that you can see which give you the room to try out new ways of relating.

Return to your relational assessment chart and add up the column of twenty numbers under each relationship. The maximum total score per relationship is 100 points (20 questions × high score of 5).

Using the following scale, sort your relationships according to these three safety groups:

HIGH SAFETY: 75 POINTS OR MORE

Relationships in this category are quite sturdy, with many 4s and 5s. A relationship in this group is a relatively safe place to try out new relational skills or to discuss concrete ways to support each other.

MODERATE SAFETY: 60-74 POINTS

These relationships are usually not the first place to turn when you need to express a difficult emotion or when you want to try out a relational skill that doesn’t feel comfortable yet. Wait until you have more practice, and then you can try applying these skills to improve the relationship. In some cases, you may decide that you are willing to take the risk of letting the person know that you are open to making things better between the two of you. You may find that if the other person has more information about how to relate differently, he or she can meet you halfway.

LOW SAFETY: 0-59 POINTS

With their many 1s and 2s, relationships that are low in safety cannot tolerate much vulnerability or conflict. It’s not wise to try new relational skills within this group, at least not right away, even if the people in this group are family members or longtime friends you feel you ought to be able to trust.

If a relationship is, frankly, abusive—emotionally, physically, or sexually—it is important for you to get help from an outside source (physician, therapist or counselor, religious leader, domestic violence specialist) to think of ways of extricating yourself from the relationship.

But some relationships in the low-safety category aren’t abusive, just problematic. Often, bad relationships are bad because they are shaped by “power-over” dynamics, in which one person is dominant and the other is subordinate. You may be able to reset those dynamics, but this process will be much easier if you work on other, less risky relationships first.

✵ ✵ ✵

Now that your safety groups are complete, do you see some of your relationships in a different way? If you need some time to absorb this new perspective, take it. Just remember that the goal of this exercise is not to search for the people who have done you wrong, and it’s not to blame your parents for the ways they raised you. The goal is definitely not to make you feel bad about the current state of your relationships. So go ahead and note any discomfort you might be having, but come back. Even if all your relationships are low in safety, you’ll learn more about how to improve your support system.

If you’ve made the rare discovery that each of your five relationships is in the safest group, please follow these instructions: put this book down, live your life, and call me. I could use some uncomplicated friends!

Step Four: Evaluate Your C.A.R.E. Pathways

Here, you’ll use the assessment to gather information about your neural pathways for connection. Once you know more about your neural pathways, you’ll have an entirely new understanding of your relationships. You’ll see why some of them are rewarding and what makes others so difficult. Better still, you can use this information to customize the C.A.R.E. program to your needs. Most people who complete this step feel more positive about their innate ability to connect and the potential to make their relational network much stronger.

Remember, these are the four C.A.R.E. pathways:

Calm, promoted by the smart vagus nerve

Accepted, via the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

Resonant, from the mirroring system

Energetic, from the dopamine reward pathways

Go back to the assessment chart that you’ve completed. For each of the twenty statements, add up the five numbers that appear across the row. Record that total under the heading “Total Statement Score.” The maximum score for each statement is 25 (a maximum high score of 5 × 5 different relationships). These totals will help you identify the strength of the four major neural pathways for connection.

Calm: The Smart Vagus

The smart vagus is a nerve that transmits signals to decrease stress. It’s also connected to your sense of relationships. Whenever you see a good friend, the smart vagus normally sends out soothing messages to your autonomic nervous system, telling your whole body to relax. But the smart vagus can get confused. You can be born with a genetic tendency to have poor vagal tone, meaning that it fails to send appropriate messages. Very stressful situations in childhood, or later in life, can also cause poor vagal tone. You may feel more threatened or anxious in social settings, and you may find it hard to trust people.

To assess the functioning of your smart vagus, add the total scores for all the statements whose C.A.R.E. Code includes the word “Calm.” This includes statements one through seven. The maximum score for the smart vagus category is 175 (seven statements, each with a possible high scores of 25).

A Calm score of 135 to 175 indicates that you have good vagal tone. Your smart vagus is able to take in the messages from your primary relationships and translate them into calming, relaxing signals. You have relationships that help you manage the stress of everyday life.

If your Calm score is between 100 and 134, you feel stressed out and anxious more often than you’d like to. This tension may be the natural result of relationships that feel somewhat risky; these stimulate an appropriate response from your sympathetic nervous system. Or you may suffer from poor vagal tone, in which case you may currently have some good relationships—but your smart vagus can’t send the stress-relieving messages that it’s supposed to. You’ll definitely want to investigate further, which you can do in the Calm part of the program.

A Calm score below 100 means that your relationships often feel unsafe; they frequently add to the stress in your life rather than diminish it. This could reflect significant problems in the quality of your current relationships. If those relationships are unsafe and unresponsive, you won’t get the benefit of the smart vagus, and your stress-response system will be continually activated. A low score here could also be an indicator of a genetic tendency toward poor vagal tone or of past abusive relationships that blocked your smart vagus’s ability to function. No matter what the cause, poor vagal tone leaves your nervous system reactive, always primed for the next attack. When a relationship feels chronically unsafe, it’s often the case that neither your vagal tone nor your relationship is working well.

Accepted: The Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex

The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex registers both physical and emotional pain. When you feel left out, it sends out a distress signal. Repeated experiences of feeling socially excluded can stress your dACC and lock it into a Fire position. When this happens, you feel all the pain of being socially excluded—even when people are trying to welcome you into their lives. To assess your dACC functioning, add the Total Statement Scores for lines five through eleven—these are all the statements with the C.A.R.E. Code that includes the word “Accepted.” The maximum score is 175 (seven statements with a possible score of 25 each).

An Accepted score of 135 to 175 indicates that your dACC is well tuned. You tend to feel safe and unthreatened in your relationships, but when you are being excluded, your dACC sends a message of pain and distress. You benefit from a helpful signal that lets you know when to trust people and when something is wrong.

If your Accepted score is between 100 and 134, your emotional alarm system is somewhat reactive. You may often feel left out or as though you do not belong. Even when you spend time with others, you may have an underlying sense of loneliness. The Accepted part of the C.A.R.E. program can help you determine whether you are truly being left out and, if so, can help you take steps toward more supportive relationships. It can also tell you if a reactive dACC is sending you mistaken signals that leave you feeling unsafe and under attack even when people would like to be friendly with you. That same step can help you calm your dACC to give you more accurate feedback.

An Accepted score below 100 indicates that your relational alarm system is being chronically stimulated. This overactive system probably results from past or current destructive relationships—but it is also distorting the way you see all your relationships, even the ones that have the potential for warmth and mutual support.

Resonant: The Mirroring System

The mirroring system allows you to read other people’s actions, intentions, and feelings with accuracy. When the mirroring system is working well, you feel a sense of resonance with others. When your mirroring system fails, you may feel that there’s a wall between you and everyone else.

To assess the functioning of your mirroring system, add the Total Statement Scores for lines twelve through sixteen. These are all the lines whose C.A.R.E. Code says “Resonant.” The maximum score is 125 (five questions, each with a possible high score of 25).

A Resonant score between 95 and 125 reveals that your mirroring system is functioning well. Your relationships feel emotionally easy; you and your friends don’t have to spend a lot of time explaining yourselves to each other. You understand most other people, and you feel that the people close to you can “see” who you truly are.

A Resonant score between 70 and 94 shows that you sometimes find other people confusing. Occasionally, important people in your life don’t seem to “get” you, and in turn, you misread people’s intentions or reactions more often than you would like. The exercises in the Resonant portion of the C.A.R.E. program can help activate and clarify your mirroring system.

If your Resonant score is below 70, you probably think of other people as baffling. You may find yourself shaking your head in bewilderment at friends and colleagues, saying, “I just don’t understand you!” Some people with low Resonant scores get into trouble because they are overly suspicious; others are guileless, naively assuming that everyone around them always has sterling intentions. And you are misunderstood as well: when you try to be kind, you get accused of being sneaky or invasive. Or maybe you give off signals of romantic interest that you’d never intended. You find feelings uncomfortable and overwhelming. If this sounds like you, go directly to the Resonant step of the program, where you can more fully assess the activity of your mirroring system. You’ll also discover ways to make subtle distinctions among different kinds of feelings—both yours and other people’s.

Energetic: The Dopamine Reward Pathways

Dopamine is the pleasure neurotransmitter. Ideally, your dopamine reward pathways are linked up with healthy relationships, so connecting with other people stimulates feelings of energy and motivation. But when your relational world leaves you drained, paralyzed, and unhappy, you may find yourself seeking dopamine from other sources. You get your dopamine hits from food, alcohol, drugs, meaningless sex, or other addictive behaviors. One way to tackle bad habits and addictions is to rewire your dopamine pathways so that you get pleasure from your best relationships instead of your worst vices.

To determine your Energetic score, add the Total Statement Scores for statements 17 through 20. These are the statements whose C.A.R.E. Code is “Energetic.” The total maximum Energetic score is 100 (four questions with 25 maximum points per question).

If your Energetic score is between 75 and 100, your dopamine pathways are plugged directly into relationships. You have good connections with other people, and those connections naturally supply you with more energy, more motivation, and more ability to act on behalf of yourself and your friends.

An Energetic score between 55 and 74 indicates that your relationships can sometimes feel unrewarding. You may have one or two relationships that you are truly enthusiastic about, but the others leave you feeling neutral and not so jazzed up. It’s a good bet that you often turn to food, alcohol, or another source of dopamine as your consolation prize. Practicing the exercises in the program’s Energetic step will help you redirect dopamine stimulation away from addictions (including “soft” ones, such as eating and shopping) and back toward healthy connections, significantly brightening your life.

A dopamine score of 54 or below reveals that the relationships in your life are draining. You may long for at least one close friendship, but you would rather be alone than participate in relationships that are unrewarding. You may rely on addictive, repetitive behaviors, such as substances or shopping, to give yourself a lift.

Step Five: Optimize the C.A.R.E. Program

You’ve got your chart, your scores, and your results. Now what? Be honest about where you’re weak and where you’re strong. Then decide how you’ll work the steps of the C.A.R.E. program. Will you do them in order, or switch them around? Do all the steps, or select just a few?

I’m going to show you how three of my clients used their results for a clearer understanding of their relationships and to customize their C.A.R.E. program.

Jennifer: From Despair to Clarity

One of the most powerful benefits of the relational assessment is that it helps you put a name on what’s bothering you. Then you can take concrete steps toward solutions.

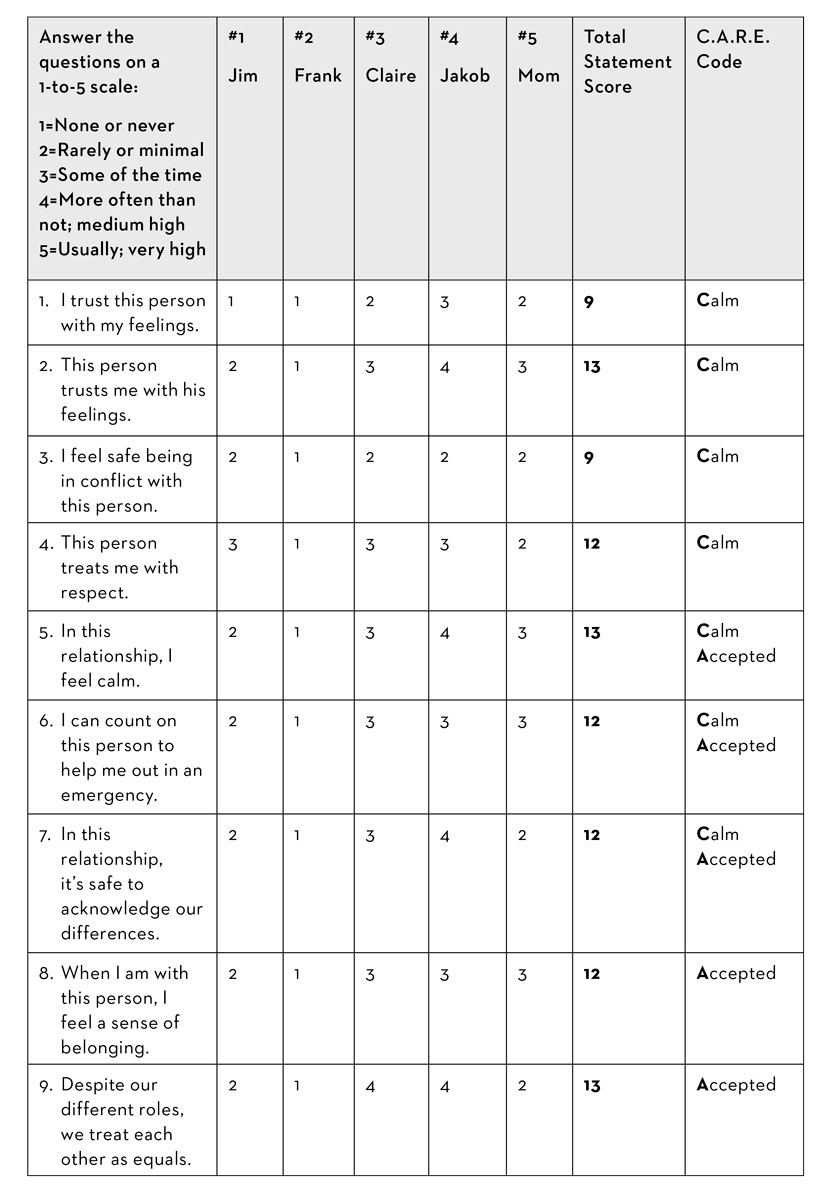

This is exactly what happened to Jennifer, who called me for an appointment after a devastating week. She and her on-again-off-again boyfriend, Jakob, had an explosive fight after Jennifer playfully criticized the suit he wore to a friend’s wedding. At the same time, Jennifer’s sister, Claire, was giving her the silent treatment. Although Jennifer recognized this as a ploy often used within the family to punish certain behaviors, Jennifer was not sure what she had done to make her sister mad. Fearing that she simply “sucked” at relationships, she turned to the only place she knew of for help: the Internet. She Googled the word “relationship” and the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute appeared.

One week later, Jennifer was sitting nervously in my office, friendly and polite but making little eye contact with me. She described the fight with Jakob and explained that the two of them had repaired the rift in their usual way: a few days after the fight, Jakob texted Jennifer and called her a judgmental snob. Jennifer, feeling she deserved it, simply took the hit. They moved on quickly from there, making plans to go out with a small group of friends Friday night. They were talking again, but the interaction did little to deepen the trust between the two of them.

Jennifer predicted that the tension with her sister would be resolved in a similarly unsatisfying way. It had been a week since Claire’s silent treatment had begun, and, Jennifer told me, she expected it to last exactly one week longer. The punishment for almost any infraction in her family, from speaking too bluntly to breaking a piece of heirloom china, was two weeks of being quietly shunned by the offended party. When the two-week period was over, the coldness thawed, and the relationship resumed as if nothing had happened.

Jennifer unflinchingly and, I thought, honestly offered detail after detail of her relational life, but she was frustrated that she couldn’t assemble these details into a coherent picture. With no better way to understand her relationship problems, she fell back on the simple but depressing idea that she was bad with people.

At this point, I invited Jennifer to complete a relational assessment, explaining that labeling herself with the shorthand “bad with people” wasn’t going to get her very far toward her goal of feeling better. I wanted both of us to have a clearer sense of the relationships that were currently shaping her brain and body.

Jennifer was drawn to this exercise. Her mind was naturally analytic—in fact, she was often accused of overthinking things by those closest to her—and she liked the idea of bringing more precision to her thoughts. She began by making a list of the people she saw during a typical week. Her list included her mother and sister; Jim, a coworker who occupied the cubicle next to hers; her boss, Frank; and her sort-of boyfriend, Jakob.

I asked Jennifer to sit quietly and to visualize a few interactions with each of these people, and to pay close attention to what she felt. Then she completed the assessment.

JENNIFER’S SAFETY GROUPS

High Safety: No one

Moderate Safety: Jakob and Claire

Low Safety: Mom, Jim, Frank

Jennifer’s first response to seeing her relational safety groups was to say, “This proves I suck at relationships!”

I countered with an important truth: no one person “sucks” at relationships. Bad relationships are always formed by at least two people. You cannot be in a bad relationship alone! We agreed to replace her self-deprecating statements with one that was more accurate: the relationships that dominated Jennifer’s life were disappointingly nonmutual.

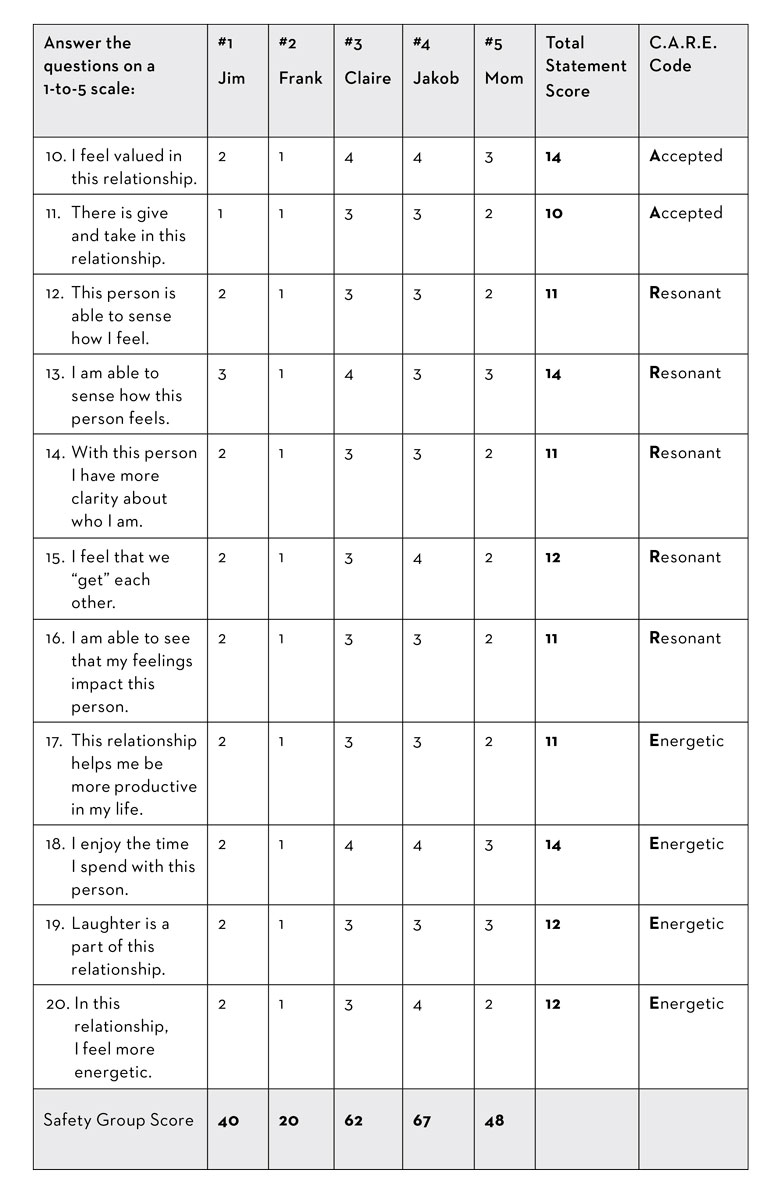

Jennifer’s C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

From there, we took a closer look at Jennifer’s relational safety groups. With two of her relationships in the moderate category and three posing a high risk, it was obvious that she had no safe, mutual relationships. This was not a shock to Jennifer. She had already told me that she really didn’t trust anyone and that if she was to be successful in life she would have to do it all on her own. But Jennifer did have a few surprises coming. She wouldn’t have thought of her relationship with her mother as particularly low in safety. She loved her mother. But after some thought, she came up with a more complex portrayal of the relationship. She recognized that it felt close but also rigid, without much room for either of them to make a misstep.

The very low scores for Jim and Frank came almost as a relief. They explained the sense of dread Jennifer felt every morning as she got ready for work at a small software company. She had to physically harden herself for an environment with an unsmiling, critical boss who openly pitted workers against one another in what seemed like a sadistic attempt to increase productivity. As we looked at her overall score for Frank, it was clear to both of us that this work relationship was emotionally abusive. Her relationship with Jim was only a little better. Although Jim was not in a position of power over Jennifer, he was generally quiet and dismissive of her.

Even at this early stage of our work together, before she had even finished interpreting her relational assessment, Jennifer had a new way of describing at least one aspect of her troubles: her relational world at work was stimulating stress pathways in her brain and body. This explained why she felt a slight but constant agitated buzz in her body throughout the week. Up until now, Jennifer had thought this feeling was just another sign that she was odd or not meant for normal human interaction.

I asked Jennifer to imagine that the five people on her chart took up all her relational time and then to determine the percentage of time she spent with each person. This is a useful imaginative exercise that makes patterns and trends more obvious. Jennifer’s percentages looked like this:

|

Person |

Percentage of Relational Time |

|

Jim |

30 |

|

Frank |

30 |

|

Claire |

15 |

|

Jakob |

15 |

|

Mom |

10 |

This breakdown made it clear to Jennifer that she spent 70 percent of her time (with Jim, Frank, and her mother) in relationships that felt unsafe and, in one case, fairly abusive. Spending that kind of time in difficult relationships can bring the rest of your relational world down, because they can adjust your template of what “normal” looks like. You can forget what respect and warmth feel like. You can forget that you even want to be treated well.

From a relational standpoint, a job change would be ideal for Jennifer—the sooner, the better. But she felt that quitting her job would be a stupid move. She visibly deflated as she realized that she knew of no other companies that were hiring.

“Is there anyone at work you can relate to?” I asked. I explained that even if Jennifer couldn’t leave Frank and Jim behind, she could dilute the impact of those bad relationships by reducing the percentage of time she spent in them.

Jennifer immediately shook her head, but then she paused. There was a new hire, Emily. They had met briefly the week before, and Jennifer had liked her energy. Her spirits lifted a little as she thought about asking Emily to lunch and seeing if they could form an informal support network. We also speculated about whether there was potential to improve things with Jim. Was he merely responding to the threatening office environment in the same way Jennifer had, by shutting down and retreating to his cubicle? Would he, like Jennifer, appreciate an opportunity for safe connection?

At this point Jim was still a question mark, but Jennifer decided she would spend a moment each day making contact, saying hello, and asking how he was doing—in a professional way, just to see if there was any softening of his demeanor.

Of all Jennifer’s relationships, the ones with her sister and her boyfriend were clearly the most mutually supportive. As Jennifer reflected on these two relationships, she felt that she was most able to be herself with Jakob. This thought came as a revelation, because they’d never had a long stretch of dating without fighting. Yet she felt more comfortable around Jakob than she did with most other people. He seemed to trust her, and she liked that feeling. A cycle of fighting and then breaking up is often a sign that something is awry in a relationship. Jennifer, however, was surrounded by people who couldn’t tolerate relational differences—when a problem occurred, they moved to disconnect from her. With Jakob, at least she had a relationship with some flexibility, in which both parties could disagree, move away, and then come back together to engage in relational repair. We decided that this relationship was the one that could most easily tolerate some stretching and growing. When the C.A.R.E. program identified exercises that could help Jennifer expand her relational skills, she’d practice them with Jakob.

Jennifer’s C.A.R.E. Pathways

Calm: 80 (low)

Accepted: 86 (low)

Resonant: 59 (low)

Energetic: 49 (low)

When we looked at her C.A.R.E. neural pathway scores, it was clear that Jennifer needed major work in all areas. Having an abusive relationship in your life, like the one with her boss, Frank, leaves lasting imprints on your central nervous system. Those changes make it harder for you to trust and feel safe with others. As we talked about this, Jennifer was reminded of her grandfather. Although he died when Jennifer was five years old, she remembered that he was a difficult man, nasty and critical of everyone around him. Were there traces of this relational style that ran throughout her family life? It seemed possible that Jennifer’s neural pathways had been influenced by challenging relationships from the very beginning, although this was a matter we’d investigate more fully at a later date.

All of Jennifer’s neural pathways were taxed. Her Calm score likely signified a weak smart vagus nerve, one that was easily overrun by the sympathetic nervous system’s stress response. Given her low Accepted score, her dACC alarm system was likely to be highly sensitive, contributing to that unpleasant “buzz” she carried in her body. And no doubt from her Resonant numbers, Jennifer’s mirroring system had taken a series of blows from the frequent periods of silent treatment her family had used to control her behavior. This was clear from her low scores and from her ongoing difficulty in making eye contact, a classic strategy for preventing connection.

Of the four neural pathways, Jennifer’s dopamine system was the hardest to read. Her overall score was low at 49, but her very low scores with the two men at work were throwing off the decent scores she had with her sister and Jakob. Despite the number, there was clear evidence that Jennifer could enjoy herself in some relationships. And she did not appear to rely heavily on external sources of dopamine. She had no addiction, not even a mild one, to alcohol, drugs, shopping, food, or the like.

Overall, Jennifer’s relational map indicated that she would benefit most by doing the whole program. The exercises in each step would help soothe and strengthen her connection pathways; she would also get plenty of education about what a healthy relationship looks and feels like. I also wanted Jennifer to think about a long-term solution to her work problem. As Jennifer developed a taste for mutual relationships, and as she left behind her self-concept as a person doomed to isolation, I was hopeful that she’d find it easier to network her way into a new job. At the very least, perhaps she could protect herself from the worst of Frank’s behavior.

Dottie: A Simple Solution to Work Stress

Dottie, a college professor and activist, was neither a wallflower nor a bully. Confident, composed, and witty, she was able to speak her mind in a variety of circumstances. Out of curiosity, she attended a workshop I was teaching, and when she took a look at the C.A.R.E. assessment, she thought: Interesting, but why bother? I already know I have a strong support system.

Dottie began the assessment anyway, quickly and easily jotting down the names of her live-in boyfriend, friends, family members, and close colleagues. But when I explained that the list should include anyone she spent a good deal of time with, her eyes widened. Her relational scales had just tipped significantly. Two of the people she saw most often were the two people who caused her the most grief. One of these people was Ken, the head of her academic department and a man she had to see on a daily basis. Throughout the years, their relationship had grown heavy with tension. Although they were mostly civil to each other, sometimes that tension broke through in faculty meetings or yearly evaluations. The other person Dottie added to her assessment was a senior colleague, Cynthia, who treated Dottie in a bossy, condescending way.

Dottie’s C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

DOTTIE’S SAFETY GROUPS

High Safety: Luca, Lisa, Kim

Moderate Safety: No one

Low Safety: Ken and Cynthia

Dottie’s C.A.R.E. Pathways

Calm: 129 (moderate)

Accepted: 135 (high)

Resonant: 87 (moderate)

Energetic: 74 (moderate)

When we looked over her assessment, it was clear that Dottie’s initial instinct had been correct: she did have a strong support system of largely mutual relationships. Although her scores for her C.A.R.E. pathways were in the middling range, it was obvious that the mostly high scores in her good relationships were pulled down by her two difficult colleagues. In a situation like this, it’s tempting to say, “Oh, well, the numbers don’t really reflect the reality. This lady has some annoying colleagues, but who doesn’t? She’s basically fine.”

Not quite. Recall the first two rules of brain change:

1. Use it or lose it.

2. Neurons that wire together, fire together.

These tell us that the brain is influenced and sculpted by what it is most exposed to, and the relationships that were sculpting Dottie’s brain on a daily basis were the ones that felt the least mutual, least safe, and most stressful. Instead of trying to work with Dottie, her colleagues Ken and Cynthia were constantly trying to establish power over her. Even with a lifetime of good relationships behind her, these two difficult relationships could powerfully affect Dottie’s thinking and feelings. Although she had thick skin and didn’t take her coworkers’ power moves personally, Dottie felt distracted and extra tired when she had to “put up” with them. She was more likely to go home and isolate herself—and maybe eat a little more ice cream than was good for her—instead of spending her free time with her boyfriend or her friends. As we talked, Dottie realized that this isolation was making things worse: the percentage of relational time she spent with her difficult colleagues was increasing.

Unlike Jennifer, Dottie did not need to do a major overhaul of her relational world, but she did need to target the two relationships that had so much negative power. She drew up a two-step plan. Dottie knew that she couldn’t change her relationship with her coworkers—she’d already tried—so she decided that they would occupy a lower ranking on the list of people she spent time with. She’d do this by increasing the time she spent in mutually supportive relationships; in essence, she’d move those good relationships up on the list. This was a pledge that was going to be difficult to honor. She thought of times when she’d been too busy to return friends’ calls or hadn’t followed through on plans to meet up. The thought of letting negative relationships shape her brain, however, was all the prompting she needed to put a few lunch dates on the calendar. She also realized that she was not using one of her most obvious sources of growth and support: her partner, Luca. After her long workdays, Dottie had been content to tuck away into her study at night, feeling the relief of not having to interact with anyone. By the time they went to bed, she and Luca had often not spoken more than a few sleepy sentences to each other. She explained to Luca what she’d learned from the seminar and they made an effort to spend more connected time together at the end of the day—not just venting their problems, but savoring each other’s company. Finally, Dottie concluded that she could benefit from the strategies in the Calm step to help her get through the inevitable meetings with her challenging colleagues. She also decided to try a few ideas in the Energetic step to keep her from turning to sweets when she needed a dopamine boost after a hard day.

A couple of weeks after Dottie returned to work, she sent me a note. Her two-pronged plan was already helping: she was feeling more energetic and had noticed a reduction in her daily stress level.

Rufus: Addicted to Energy

Rufus saw himself as an ordinary guy with a big problem. He’d graduated the year before from a local community college and found a job within three months at a biotech company. He liked his job, but to him, a job was just a way to make money and pay his bills. It was not a passion and never would be. He was a guy who was comfortable living an anonymous life—again, this is how Rufus described himself to me—without major highs and lows, a guy who did not stir extreme reactions in anyone. He was part of the background, blending into the fabric of life. He looked forward to weekends and hanging out with some of his buddies, drinking a few beers and watching whatever game was on television. He dated occasionally, but no one had swept him off his feet.

Three years ago, when Rufus was eighteen, he discovered Internet porn. He was online looking over his next picks for his fantasy football team when a pop-up screen appeared in front of him featuring a provocative picture of a young woman. He wasn’t sure why he clicked through. In retrospect, he thought he might have just been bored. What Rufus discovered going through this portal was a virtual world he never knew existed. He had heard his friends describe images they’d seen online, but he’d always assumed they were making up most of the details.

That night Rufus stayed up until four a.m. roaming from one porn site to another, each one giving him a little hit of energy. This was a new feeling for him, very different from his predictable, mellow life. He was not even sure he liked this feeling at first. It was unfamiliar and uncomfortable. But he returned to the site the next night, and the next.

Very quickly, Rufus was spending hours every night browsing for new and different porn sites. He shared this new world with no one and figured the only drawback was that he was getting less sleep at night. After three months of staying up late and dragging himself to work in the mornings, he realized he was hooked and tried to cut back, but was simply unable to. It was as if the websites had taken over his brain and body. Rufus came to my office when he found himself unable to resist sneaking peeks at work during lunch or whenever he felt bored. Before he was caught using his work computer for porn, he said, he wanted to get control of himself.

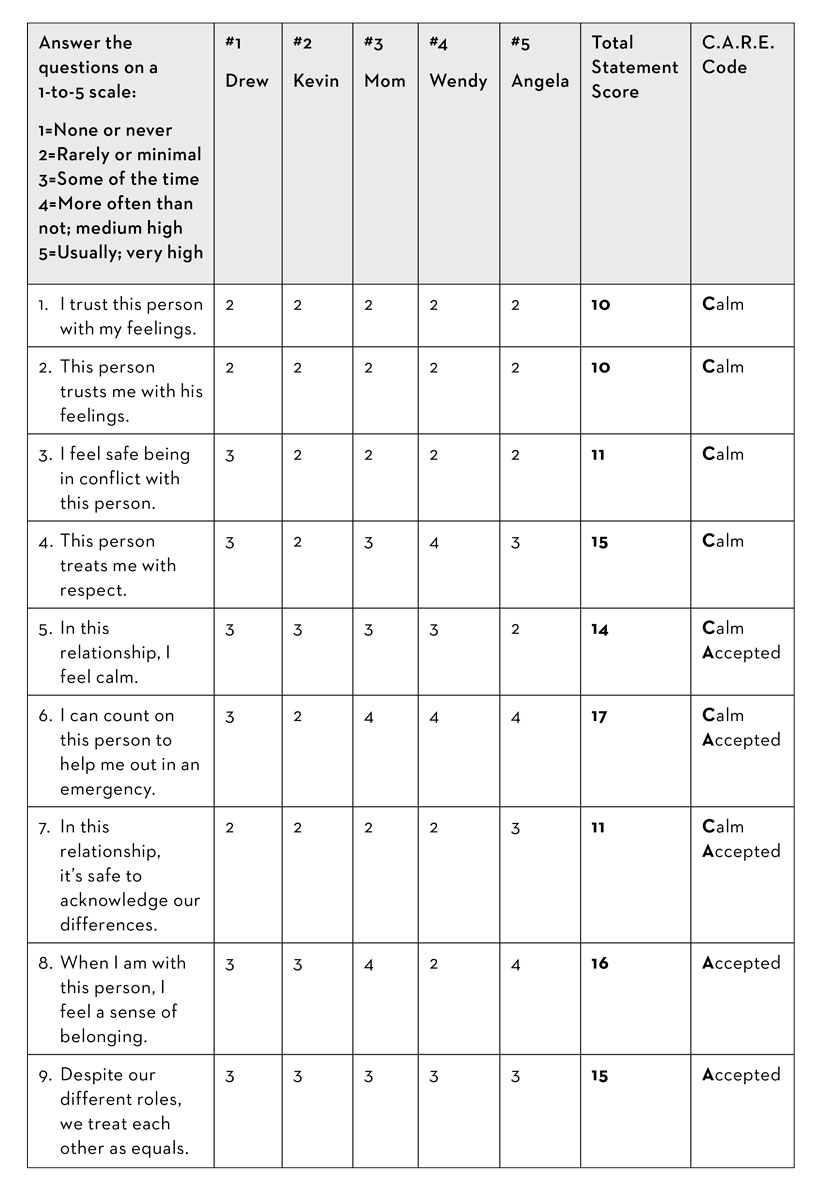

I explained that although we would clearly have to address the big problem of porn, addictions rarely happen in isolation. We’d use the C.A.R.E. assessment to create a more complete picture of his world. When I asked Rufus to come up with the five people he spent most of his time with, he quickly mentioned his card-playing buddies, Drew and Kevin. Rufus loved his mother and sister, Angela, and usually had some contact with them during the week, so they were listed. But after that it was slim pickings. I needed to prompt him about work relationships, and he did not seem to think of his colleagues as people with whom he had relationships. They were simply people at work. Then he came up with Wendy, who sat in the cubicle kitty-corner from his. Although Rufus was surrounded by coworkers, Wendy was the only one who made an impact on him. She often had a smile on her face and always asked how his latest project was coming along.

Although Rufus was nearly stumped by the task of coming up with five relationships, completing the questionnaire was easy for him. In fact, as Rufus went through the questions, his answers were unusually concrete. Most people worry a little over their answers and have the urge to fiddle with them, but Rufus didn’t. I wondered whether he was unable to access his feelings well enough to form nuanced impressions of his relationships. Or perhaps he was merely decisive.

It was tempting to think of Rufus as a person who suffered from a straightforward case of addiction. Fix the addiction, problem solved. But the relational assessment showed us that unless Rufus attended to a few other areas, he’d have very little chance of beating his addiction in a permanent way.

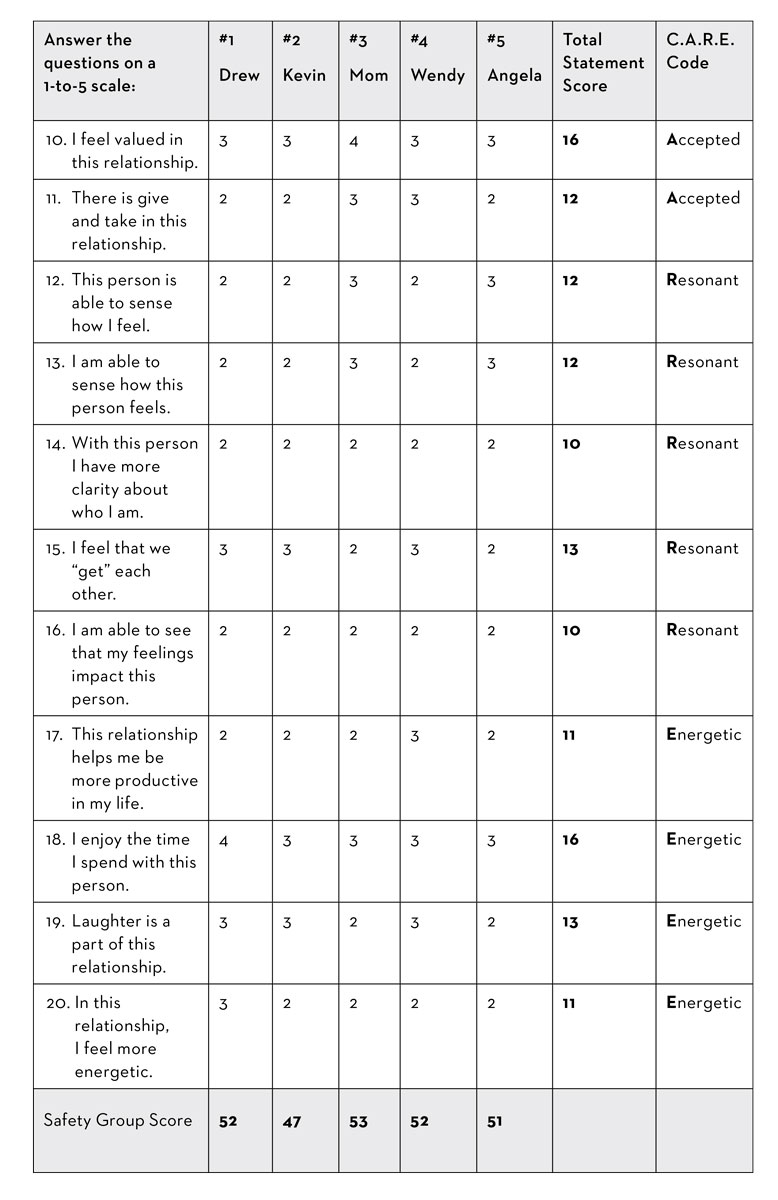

RUFUS’S SAFETY GROUPS

High Safety: No one

Moderate Safety: No one

Low Safety: Drew, Kevin, Mom, Wendy, Angela

Rufus’s C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

Given Rufus’s self-definition as someone content to blend into life’s scenery, doing his own thing, it was not surprising that his overall scores on his assessment show that he was deprived of growth-fostering relationships. There was little variation in how he scored each relationship (the scores stayed between 47 and 53, only a six-point difference), and each of them was in the lowest category of relational safety. This fit with my sense that not only would Rufus have a hard time finding relationships to stretch in, but that he also had very little knowledge about how he might do this. The C.A.R.E. plan is always based on making small, unthreatening changes, but with Rufus, we’d have to be extra cautious in how we proceeded.

Rufus’s C.A.R.E. Pathways

Calm: 88 (low)

Accepted: 101 (moderate)

Resonant: 57 (low)

Energetic: 51 (low)

There’s a saying among physicians that the presenting problem—the problem that clients identify as their main issue—is never the real problem. That’s not quite true. Porn addiction was definitely a real problem and a serious threat to Rufus’s job and well-being. But although Rufus came in specifically for help with his addiction, it wasn’t the whole story. He didn’t have the exact words for it, but he seemed to want me to know about a curious flatness in his life. He claimed to like his routine, but he gave no sign that his life was satisfying. “Inert” was a better word. Porn gave him not just sexual gratification but a missing spark of energy. In fact, it was the hit of energy that brought him back to porn again and again. Until Rufus completed his assessment, this energy problem hovered in his peripheral vision, almost out of sight. When he looked at his numbers, he could see it clearly.

Remember, dopamine is what gives you good energy and motivation. When Rufus and I looked at his assessment, we saw that his Energetic score—which reveals the ability to get dopamine from relationships—was very low. No surprise there. Here’s what was interesting: some people with low Energetic scores are in difficult, constantly frustrating relationships. Others have almost no relationships at all. That makes sense: bad relationships, or no relationships = low dopamine. But Rufus’s relationships were actually okay. Not intimate or satisfying or truly safe, mind you, but okay. He liked hanging out with his buddies and his family. You’d think he would get at least a middling amount of energy from these contacts, but he was getting almost none. No wonder he didn’t feel motivated to do any more at work or in life than he absolutely had to.

Was Rufus just a guy who didn’t need people? No. Everyone is born with the capacity for getting dopamine from connections with people around them. Somewhere along the way, Rufus’s dopamine system had become disconnected. His brain was like a toaster whose electrical cord had been unplugged from the socket. The socket can provide energy, but the signal can’t travel down the cord to the toaster. The result: no toast. In Rufus’s case, no mental energy, either.

The low Energetic score accounted for some of the flatness Rufus experienced, but not all of it. Look at the rest of his assessment. It describes a person who is not anxious or sad or irritable, which is a good sign. It also shows someone who does not have easy access to emotional information. For example, Rufus’s Resonant score was also low, almost as low as his Energy. He had a hard time reading people or knowing when other people were accurately reading him. His Calm score, at 88, was also low; this was mostly due to the march of 2s across the statements about sharing feelings. At 101, his score for Accepted was in the moderate category (we celebrated this small victory), reflecting he felt safe and not overly stressed. He explained that he felt a definite sense of belonging with his mother and sister and that it never occurred to him that he might be ostracized with his friends or at work. I was glad that he was tight with his family; but in the rest of his relationships, he seemed to be missing something. Again, it wasn’t that he had a bad feeling about his friends or colleagues; it was that he didn’t have much of a feeling about them at all.

All in all, the relational flatness in Rufus’s brain and body was a perfect setup for an addiction. Yes, he liked the porn itself, but he was really addicted to the feeling of finally having his dopamine system stimulated. As he said, he felt energized after viewing porn, in a way he’d never felt before.

Rufus needed a plan that would help him to do two things: reconnect his dopamine reward system to relationships (not porn), and develop more knowledge about how people interact. It was clear that Rufus would benefit from the entire program. But in his case, it made sense to rearrange the order of the steps.

ENERGETIC: Rufus’s Energetic (dopamine) problem was the most urgent. He’d start with this step, which would help him disconnect his dopamine reward pathways from porn and reconnect them to healthy relationships.

RESONANT: By increasing the strength of his mirroring system, Rufus would make his connections to other people more satisfying. This would give him a larger supply of good feelings to send down the dopamine trail, resulting in more energy.

CALM: Although a low score here often results in anxiety or stress, Rufus seemed fairly placid. By increasing his vagal tone, he’d feel something richer than the blank dullness he was accustomed to. He’d feel content.

ACCEPTED: Rufus’s dACC scores were decent, and he was not particularly concerned about having a sense of belonging. At this point, we decided not to focus on this step. I felt that as he developed a more textured sense of relationships, it was possible that he would begin to worry about inclusion or exclusion. If that happened, we could always go back and add this step.

We now had the outline of a plan. I didn’t expect the plan to turn Rufus into Mr. Sensitivity, and I don’t think he wanted the title. But I knew that if he could see life with a broader palette of relational colors, he would do more than end his addiction. He’d feel more animated and alive.

Ready to begin the C.A.R.E. program? The next step—strengthening the smart vagus to feel Calmer—begins on the next page.