Impossible to Ignore: Creating Memorable Content to Influence Decisions - Carmen Simon (2016)

Chapter 8. BECOME MEMORABLE WITH DISTINCTION

How to Stay on People’s Minds Long Enough to Spark Action

Who is your favorite superhero? Captain America, Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Wolverine, Jean Grey? The question may be tough to answer because these days there is superhero overload. At one point, Dash, from the Incredibles, is told by his mother, “Everyone is special, Dash.” And he responds, “Which is another way of saying no one is.” I am noticing a similar trend in content creation: when people treat every single piece of content as “special,” none is. And the result is forgettable.

One way to avoid forgettable content is to make it distinct from what your audiences see elsewhere. We discussed distinctiveness in Chapters 1 and 4 to show how distinct cues draw attention. However, it is one thing to draw viewers’ attention to a distinct stimulus and another for them to remember that stimulus long term. The purpose of this chapter is to explore that concept further, offer scientific explanations as to why distinctiveness works for long-term memory (not just attention), and provide practical guidelines on how to use it in your own messages.

WHY DISTINCTIVENESS WORKS FOR LONG-TERM MEMORY

Scientists consider memory to be ultimately a discrimination problem: when something stands out compared with neighboring items it commands a privileged spot in memory. This theoretical framework was introduced almost eight decades ago when Viennese psychologist Hedwig von Restorff completed a study in which she presented participants with either a list of nine numbers and one syllable or a list of nine syllables and one number. She reported higher recall of the isolated items. This is called the von Restorff effect, or isolation effect.

Ever since this classic experiment, many other researchers have investigated the isolation effect in different variations to test memory: presenting subjects with a list containing the same items and changing the physical property of one of the items (e.g., different color, size, weight, sound, or frequency); mixing materials by including an entirely different item in a list with the same items (e.g., a number inserted in a list of words); or making something incongruous at a semantic level, such as the meaningfulness of an item (e.g., mixing something irrelevant with what is relevant). In many of these experiments, subjects showed better recall for the distinctive item.

More recently, researchers have focused on not only what makes something distinctive but also why the isolation effect impacts memory. Researchers realized there is more to distinctiveness than isolation of physical properties. This can be demonstrated if the control element used for isolation in one experiment is placed on a list in which it is no longer considered an isolate. While the color red is distinct when it appears among words printed in black, it is no longer distinct when it appears near red words that hold the same physical characteristics.

While these observations may seem intuitive, what is not so obvious is why distinctiveness is memorable. Explanations are mixed. We’ve already read about isolates drawing more attention, therefore more rehearsal time, or provoking surprise, which in turn increases attention and therefore recall. Some researchers attribute the isolation effect to gestalt theory, according to which homogeneous items share the same memory trace and may lose their identity in the background, while the isolated items come to the foreground and are identified as distinctive.

It is possible that isolating items helps recall because it reduces interference from other elements that are too similar. Researchers suggest that when the brain detects differences between isolated and background items, encoding results in two categories: the isolated items and the background items. Since the isolated items represent a smaller category compared with the background items, recall is better for isolates. The probability of retrieving an item from one of the two categories is inversely proportional to the size of the category. This is why when we create content, it is useful to ask:

1. How many items do we want to isolate?

2. Do they represent the most important content we want others to remember?

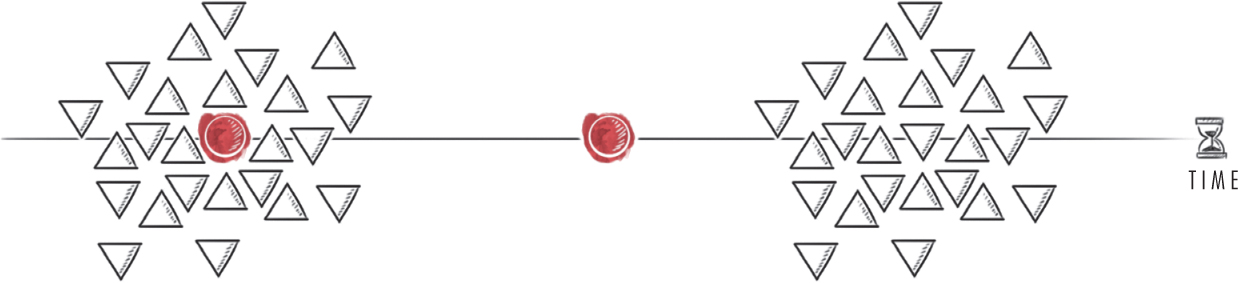

It is practical to regard any messages you create as a set of items placed along a temporal continuum (e.g., a set of paragraphs in an e-mail or blog, a set of sounds in a meeting, a set of slides in a presentation, a set of campaigns in a marketing initiative). Audiences can discriminate between items depending on their position along this continuum. Similar items that crowd a psychological space are harder to discriminate compared with something that is distinct in a crowd or that does not have much in its close proximity. Cognitive psychologist Gordon Brown says, “The retrievability of an item is inversely proportional to its summed confusability with other items in memory.” In other words, the more similar things are, the harder it will be to retrieve them later. This statement reminds us that distinctiveness is not only useful for drawing attention; it is useful for memory retrieval.

IT IS EASIER TO REMEMBER ITEMS THAT ARE DISTINCT IN A CROWD OF SIMILAR ITEMS OR ITEMS WITH NO “NEIGHBORS”

Here is what happens in places filled with similarity. The following are excerpts from real value propositions created on the topic of predictive analytics and Big Data—an increasingly crowded space. I showed them to employees from one of the companies that created one of the statements, and removed the logos so they did not know which was part of their own messaging.

“We help uncover valuable insight from Big Data with the ability to access and combine unstructured or semi-structured data so you get improved predictions and optimal performance.”

“We leverage business rules and predictive analytics to take the best action based on real-time context and maximize the value of every customer interaction.”

“Using our tools, you can create a predictive modeling environment for both business analysts and data scientists, and give them the automated tools they need to build sophisticated predictive models for every data mining function.”

Only 1 person out of 40 knew which message belonged to his company. When distinctiveness is absent, we end up creating content for our competition because two days from now, a prospect will find it difficult to remember who said what. It is possible to fix this.

Are you occupying a place that’s already crowded in your audiences’ minds?

Imagine if a company offering predictive analytics and Big Data tools said this instead: “Using our predictive algorithms, we prevented account closures at a bank and attrition dropped 30%.” This remark comes from EMC data scientist Pedro Desouza, who adds that his company helped the same bank to “reduce the cost of Big Data analytics from $10 million to $100,000 per year.” Another Big Data firm worked with a shipping company that handles 4 billion items per year and uses 100,000 vehicles. The Big Data firm created on-truck telematics and algorithms to identify and predict routes, engine idle time, and truck maintenance. Imagine if its message read, “Using our predictive analytic tools, we helped our shipping customer save 39 million gallons of fuel and avoid driving 364 million miles.”

The brain is constantly looking for rewards. In business, when many messages are the same, we can create distinctiveness, and therefore improve recall, by being specific about these rewards, which we can frame as tangible results. Reflect on your own content: Can you identify specific outcomes of your work that help you differentiate your message from too much sameness in your field?

ABSOLUTE UNIFORMITY IS FORGETTABLE, BUT SO IS ABSOLUTE VARIETY

Neuroscientists remind us that an item will not be perceived as distinct if it is embedded in a series of varied items. The first red circle can be harder to recall when it is surrounded by too much variety. The second circle can be memorable when it is isolated.

TOO MUCH VARIETY MAKES IT HARDER FOR AN ITEM TO BE PERCEIVED AS DISTINCT

The irony is that similarity is mandatory for enabling distinctiveness. Think of it this way: after many formal meetings in an office, a meeting in a coffee shop is distinct. After many days of driving to the store, walking to the store is distinct. Something becomes distinct after periods of similarity. Reflect on your own content and approach to business: if you’re not first to market, observe pockets of similarity in your domain and then strike with distinctiveness. Allow your audiences’ brains to habituate to similarity; it will be easier for your message to stand out.

To perceive distinctiveness, we must perceive similarity.

DETERMINE THE DEGREE OF DRAMA

Isolating an item from its neighbors impacts memory for that item, but what does it take to make a stimulus distinct? And does the isolation effect happen at the expense of what comes after it? In other words, are we sacrificing some elements in our communication in favor of isolates? It is useful to consider the intensity we apply to distinct items because when something is too strong, neighboring items may be forgotten.

In most isolation experiments, the more an item differs from other items, the bigger the size of the effect. The largest effects have been obtained using size, color, and spacing manipulations, and in many of these cases, the degree of “intensity” from a nonisolate to an isolate was a minimum of 30%. In one study, researchers used items of four sizes, each being 70% of the next largest size. They reported that the isolation effect increased as the contrast between the isolate and the background items increased. Bigger is better to ensure the isolate is indeed distinct.

Many brands use exaggeration or hyperbole as a means of distinctiveness, which leads to long-lasting memory. Does America really “run on Dunkin’”? And if we buy Oscar Mayer, is it true that “it doesn’t get better than this”? An Old Spice ad shows a handsome man in the bathroom, wearing 20 gold medals and carrying a chain saw over his right shoulder. Yet he’s wrapped in a towel and standing between lit candles. The exaggeration goes in both directions: you will be manly and romantic if you use Old Spice.

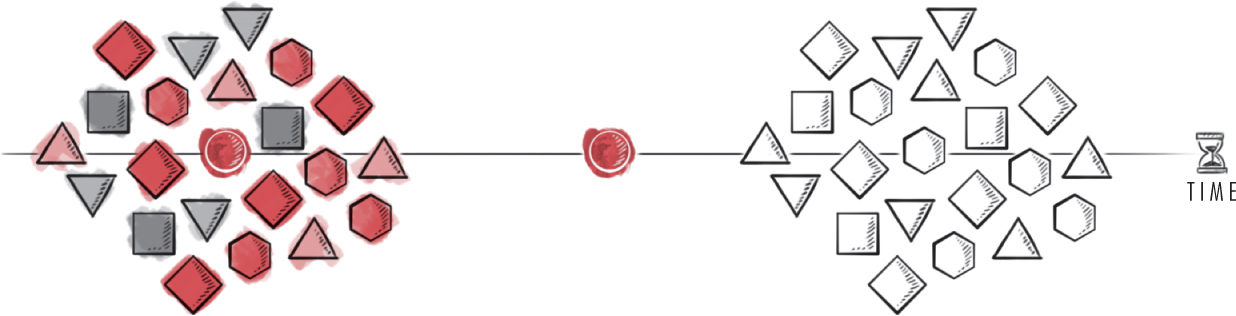

In this slide, the presenter’s message was that when we don’t have the capability of targeted marketing, consumers receive ads for the wrong products. The presenter exemplified this with exaggerated associations: the bodybuilder receives products for the knitter and vice versa.

EXAGGERATION WORKS WHEN IT IS DRAMATIC

Cautious communication does not always stay on people’s minds long term. Analyze your content and find opportunities to deviate from a reality that your viewers have learned to expect. Keep in mind, however, that in the process, neighboring items may be sacrificed. For example, one study found high rates of recall for distinct items in a slide presentation but also showed a deficit in recall of items following stress-provoking stimuli, such as a traumatic autopsy slide. The proportion of reality versus amplification results from how much we want the isolate to be remembered and whether it is acceptable for a few items that follow to be forgotten.

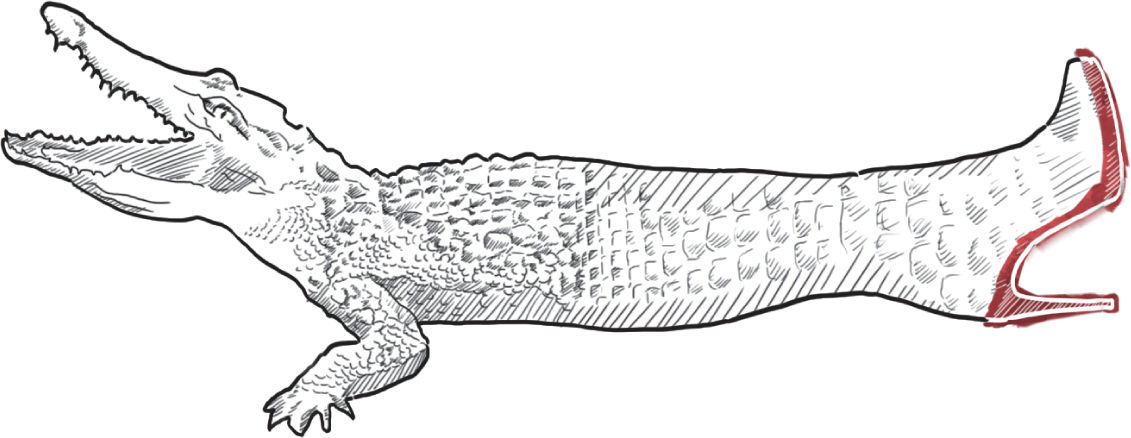

WHEN YOU DISREGARD ACCURACY, YOU COMMAND ATTENTION AND IMPACT MEMORY

There is a paradox about elements that clash with their environment and get attention and a memory slot. Some studies demonstrate that, initially, memory for what deviates from an expected pattern is better for something considered typical and expected. However, other findings remind us that if the deviant stimuli do not confirm the internal beliefs or schemas we have, they eventually become filtered out because they are inconsistent with our core beliefs. Reflecting on your content, consider creating something that is distinctive yet fits in with what an audience considers rewarding. This way, you have the best of both worlds: a distinct element that attracts attention, is not filtered out, and stays on people’s minds long term.

CREATE DISTINCTIVENESS BY THINKING IN OPPOSITES

If distinctiveness is providing a stimulus that is different from neighboring items, we can create it by choosing the opposite of what an audience just saw. This idea may be easy to understand, but opposites are not always easy to identify because not everything can be described in opposition. For example, science and philosophy remind us that black and white, hot and cold, or good and evil are not really opposites. They are part of a spectrum, not binary opposites.

It is useful to consider opposites from a contextual angle, with a fuzzy-trace approach. In underdeveloped nations, rich and poor consider themselves opposites, but an outsider from a well-developed nation may consider them both poor, and not opposites at all. What matters in your content creation is: What does your audience consider the opposite of what you presented for a while?

Some stimuli that our listeners experience may indeed be considered binary in a universal way. Elements such as on-off, entrance-exit, pass-fail, and dead-alive provide inspiration for opposites with little room for subjectivity. If your content has precision, this can be a starting point for creating distinctiveness with complementary opposites. For example, a lot of business content currently alludes to the dichotomy of dead versus alive. In discussing the concept of disruption, people speak about dead businesses, such as Circuit City, Borders, or Blockbuster, versus the ones that are alive and well, such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Netflix. In a recent presentation, I heard Raj Verma, executive vice president of worldwide sales at TIBCO Software, use this binary contrast between dead and alive business models to ask the audience, “Are you on the right side of history?”

Relational opposites are another source of distinctiveness. In pairs such as above-below, doctor-patient, borrow-lend, take-give, and buy-sell, both items must exist to perceive contrast. For example, we typically associate brands having a goal to make money (take). When they act altruistically (give), they capture attention, such as a Giorgio Armani campaign that announced “Smell good, do good.” The ad promised that for every bottle of perfume sold within a specific week, the company would donate $1 to the UNICEF Tap project, a nationwide campaign that provides children in impoverished nations with access to clean water.

If your content includes relational aspects, allow your audiences’ brains to habituate to one dimension and then switch to the other to be perceived as distinct. I once worked with Chris Cabrera, CEO of Xactly, to create a presentation about the company’s incentive compensation program. The theme of the presentation was that ideal incentives drive business. In order for this to happen, a company’s goals must be exactly aligned with a sales team’s goals, which is not always the case. To visualize the contrast in this lack of alignment, we started the presentation by showing the different goals of a house seller and his agent. “Imagine a homeowner who wants to sell his house for $1M,” Cabrera said, “and hires a real estate agent for a 3% sales commission. The next day, the agent finds a buyer willing to pay $900K. So he can either push the owner to sell at $900K and cash his $27K check for one day of work or continue to look for another buyer for an indeterminate amount of time, for the extra $3K. What will the agent do? What would you do if you were the agent?” Using relational opposites, Cabrera made the point that “this is what happens when two entities have different goals. The same misalignment occurs in corporations.” I remember this introduction vividly even though we worked on it seven years ago.

A third category of opposites is graded, meaning that there can be various levels of comparison on a scale. Pairs such as young-old, hard-soft, happy-sad, small-big, fat-skinny, early-late, and fast-slow are relative and can be interpreted in various ways by different people. This is where fuzzy-trace theory helps to distinguish, based on your audience and prior experiences and expectations, what level of contrast and distinctiveness will be perceived. For example, imagine seeing this ad from Haagen-Dazs: “Who says bigger isn’t better? Introducing the new 14 oz.” This will be seen as distinct to existing consumers who can contrast it against much smaller container sizes, but not to people who don’t eat ice cream or are not aware of previous sizes.

HSBC is a master at creating content that plays off opposites. Imagine a picture showing several standing carrots and labeled “Order” and one with carrot soup, labeled “Chaos.” The picture next to it shows the same pair of photos but with the labels reversed. In other ads, HSBC swaps the labels of “useful” and “useless” for pills and herbs, “pleasure” and “pain” for shoes and chili peppers, and “good” and “bad” for papaya and chocolate. The message is to be open to various points of view. The graded approach to contrast has made the campaign widely popular.

Including opposites in content design is helpful not only because it helps the brain distinguish some stimuli more strongly than others, but also because contrast is a shortcut to thinking and decision-making. For example, I helped someone with a presentation expressing the dichotomy “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” We used Dickens’s quote to describe the economy. If you are providing value, it is the best of times for a business; if you’re not, then it is the worst of times. The presenter allowed the audience to habituate to a few examples of companies providing value (GE, Apple, and Facebook), and then switched to companies experiencing the worst of times, such as companies offering LAN lines. The contrast captured attention and evoked emotion, which result in long-term memory. The message and visuals are still on my mind, and I created this presentation three years ago.

ENABLE SELF-GENERATED DISTINCTIVENESS

Memory literature offers abundant evidence that in situations when listeners have the opportunity to generate content on their own, they are more likely to remember that content better compared with the same information given to them by someone else.

It is easier to remember how you solved a problem than trying to memorize someone else’s solution.

Anything related to the self leads to better memory because we implicitly pay more attention when we are invited to be active versus passive. We create better associations between new content and existing internal schemas and have better cues for later retrieval.

Imagine for a moment you’re a runner. Which route would you remember more in a few days: one you just completed that someone else had recommended or one you just completed but generated yourself? Claire Wyckoff, an advertising copywriter in San Francisco, has been gaining in popularity as a “running-route artist.” She generates her own running paths in order to create specific shapes. Currently, fitness trackers such as Strava, Garmin, and Nike+ allow you to record not only the distance you run but also the shape in which you run it. The company MapMyRun launched a contest in 2014, inviting people to submit images of their most creative running routes. The pictures included robots, guitars, and animals. A run around Golden Gate Park and some adjacent neighborhoods in San Francisco took the shape of a corgi. We can be sure Claire remembers these paths very well because they require extreme attention, repetition, self-generated cues, and tools that help along the way. So far, she’s made more than 20 street drawings, including Slimer from Ghostbusters, a pilgrim’s head, and a birdcage in honor of Robin Williams. And she laughs at the benefit. “Mapping a drawing, I’m way more engaged in the process of running it,” she says. “I’ll go an extra five miles if it means finishing a picture.”

Neuroscientists confirm that self-reference improves long-term recall. For example, when subjects are given a list of traits (e.g., lazy, honest), they tend to remember those words better when they are asked “Are you lazy?” or “Are you honest?” versus “Is this a desirable word?” or “Does this word seem familiar?” or “Have you read, heard, or used the word recently?” Any encoding that leads to evaluative processing is linked to improved memory.

As you create content for others, invite them to answer the questions “How does this content represent you?” “Where does it fit within your reality?” and even “In what ways are you like this content?” For instance, returning to an earlier example on predictive analytics, the three Vs of Big Data are velocity, variety, and veracity. If we want our audiences to remember the three Vs, we could ask, “In what ways do these words describe you?” It will be much easier for them to remember these words in three days when applying a self-reference elaboration method versus simply seeing a list. The self-generated content will be active and distinct compared with viewing other content passively.

ACHIEVE DISTINCTIVENESS WITH A HUMAN TOUCH

If we consider distinctiveness “departure from the expected,” a deviation that many will appreciate and find impossible to ignore is one with a human touch. We create our communication in the service of other people. Notice what happens when we shift from a formal, technology-oriented message to an informal, human-oriented language. “When I’m not deep into algorithm design, data modeling, or analytic visualizations, I really like to ski,” says Pedro Desouza, the data scientist from EMC we met earlier.

Consider this excerpt from an interview with Robert Altman, the legendary director of MASH, in which he recalled his experience during World War II. Notice the transition from plain facts to remarks about human nature, which makes his response more distinct. What will you remember more? “I was a pilot. I flew a B-24 in the South Pacific. I did forty-six missions, something like that. We got shot at a lot. It was pretty scary, but you’re so young; it’s a different thing. I was nineteen, twenty, it was all about the girls.”

Notice how former Russian president Mikhail Gorbachev, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, distinguishes an other wise detached message with a personal touch. In the 1990s, he founded Green Cross International, a global, nonprofit environmental organization. Given his serious approach to ecological issues, Mr. Gorbachev is often asked why he decided to star in a Louis Vuitton ad. He responds, “The proceeds go to Green Cross International and its American counterpart, Global Green.” He adds, “Also, I travel a lot and a good bag comes in handy.”

Patagonia’s CEO Rose Marcario also achieves distinctiveness with a human touch. Recently, she embraced an environmental approach to business for her company. Patagonia advises consumers not to buy its clothes. By doing so, it sacrifices some of its earnings. The company also shares product breakthroughs with competitors—all in an effort to cause less wear and tear on the environment. The message in Patagonia’s paradoxical campaign “Don’t buy this jacket” is do not buy more than you need.

I remember a presentation by a pharmaceutical professional during a workshop I gave. Most of her presentation focused on critical and fairly technical matters. As she drew to a close, she left us with a video of a woman who, before getting double-mastectomy surgery, danced with the medical staff to Beyoncé. We were all compelled to get up and dance. I polled the class a week later, asking what everyone remembered. All 30 participants mentioned this moment. No exceptions.

Can you identify ways to create distinctive content using a human approach to business?

CREATE DISTINCTIVENESS (AND ACTION) WITH MEANING

Joshua Glenn and Rob Walker are two writers who collaborated on a literary and economic experiment between 2009 and 2010, to discover whether adding meaning to an object would draw attention and sway people to buy it for more money than it’s worth. They bought knickknacks at thrift stores for a total of $129. They paid no more than $2 per object and asked various writers to compose a story for each object. Then they posted each item with its story on eBay and watched what happened.

A beat-up motel room key cost them $2. The story, written by novelist Laura Lippman, began with a wife putting away her husband’s knickknacks. She asked him why he had kept the key for so many years. On the key was engraved Perkins Motel, Laconia, NH, Room 3. The husband replied that the key reminded him of the movie Psycho (the actor’s name was Anthony Perkins, which he thought “was cool”). When the wife was unimpressed, he mentioned a trip to that motel with a “bunch of guys” in junior college and he forgot to return the key and has had it since. “Here’s the moment where you choose to believe, or not to believe,” the wife reflects. “A marriage is a kind of religion, defying rational thought.” She realized that motel rooms no longer use traditional keys anymore, even in Laconia, New Hampshire. Whatever memory her husband treasured may have been beyond one shared with a “bunch of guys.” She wondered if he wanted to keep the story to himself, for her sake or his, and not spoil what may have happened in Room 3.

The key sold for $45.01.

The writer Ben Ehrenreich tells the story about a jar of marbles and starts with an irresistible statement: “I pull a marble from your skull each time we kiss. ‘Give it back,’ you say, each time.” The rest of the story is a surreal dialogue between two people during which we move from hunchbacks, to Noam Chomsky, to Beyoncé, to the narrator’s lover arranging TV remotes attractively, to Vladimir Putin in the form of a crow, being the narrator’s friend on Facebook. When we get to the final scene, we are left with this paragraph to ponder: “And I kiss your fingers and your dry lips and with my free hand I reach up and I stroke your hair and I poke about until I feel the bulge and then I dig in with my nails and pull another marble from your skull.”

The jar of marbles was bought for $1 and sold for $50.

Overall, the Significant Object project made $8,000 and beautifully illustrates the impact of meaning in making decisions.

Reflecting on your own content, consider this: At any moment, the world is filled with sights and sounds that simultaneously compete for your listeners’ attention. The human mind is limited in its ability to process information and selects only relevant stimuli that receive priority for further processing. In a world of constant data explosion, how do we create meaningful content that leads to recall and influences decisions?

Give your audiences the thrilling relevance of Room 3.

KEEP IN MIND

✵ Distinctiveness is important for long-term memory because isolated items draw more attention and rehearsal time. In addition, isolated items come to the foreground, reducing interference with other items, and also appear in smaller numbers, which makes them easier to recall long term.

✵ The more similar things are, the harder it will be to retrieve them later. However, similarity is important for the brain to detect distinctiveness.

✵ The brain is constantly looking for rewards. In business, when many messages are the same, we can create distinctiveness, and therefore improve recall, by being specific about these rewards, which we can frame as tangible results.

✵ If you’re not first to market, observe pockets of similarity in your domain and then strike with distinctiveness. Allow your audiences’ brains to habituate to similarity; it will be easier for your message to stand out.

✵ The more an item differs from other items, the bigger its effect. Select a property you want to isolate and increase its distinctiveness by at least 30% compared with neighboring items.

✵ Find opportunities to deviate from a reality your viewers have learned to expect.

✵ Create distinctiveness by thinking in opposites. This is helpful not only because it helps the brain distinguish some stimuli more strongly than others, but also because contrast is a shortcut to thinking and decision-making.

✵ Enable self-generated distinctiveness.

✵ Achieve distinctiveness with a human touch and deep meaning.