Pagan Portals - Guided Visualisations: Pathways into Wisdom and Witchcraft - Lucya Starza 2020

Annwfn and the realm of Faery

Twrch Trwyth will not be hunted until Gwyn son of Nudd is found — God has put the spirit of the demons of Annwfn in him, lest the world be destroyed. He will not be spared from there2

Annwn, (pronounced Anoon) or in its earlier form, Annwfn (Anooven) means ’the deep place’ and is the Welsh name for the spirit realm or the underworld, over which Gwyn is traditionally held to be guardian and lord. Over the Christian era this became understood as a Welsh version of hell. According to this quote above from The Tale of Culhwch and Olwen, (from the collection of Welsh traditional tales, the Mabinogion and first recorded in the White Book of Rhydderch circa 1325) we can see that even in this later Christian era Gwyn is given a high status, and must be considered to be a figure of great goodness and power, even if with a somewhat terrifying reputation as he is tasked with the restraint of all the ’demons’ of Annwfn, ’lest the world be destroyed’. In a Gaulish curse tablet there is a reference to antumnos which may have the same root as Annwfn and comes from the Gallo-Brittonic word ande-dubnos meaning the underworld, the dark place. Yet the Welsh underworld, and indeed the underworld in the Celtic tradition generally was not a place of darkness or judgement as it’s commonly understood in a monotheistic world view. Rather it is a place of paradisal delight and beauty — of ease and deep soul connection with the land and its spirit inhabitants, the faeries, together with the gods. When we consider the name ’the deep place’ a whole host of connotations arise, that not only a place deep underground or below water is referred to, but perhaps also somewhere deep inside reality as well as deep inside the human heart itself.

Annwfn often reflects the surface world. There are tales that suggest a form of learning takes place for those who come there, as well as an opportunity for healing and rest — it seems to be a place where the soul can re-set itself after the trials and woes of the mortal world, where some reconnection can take place with the inner vivifying qualities of the land.

Annwfn, like other Celtic forms of the underworld or Otherworld can be accessed via visionary or physical journeys into the earth itself, via barrow mounds and hollow hills, but it can also be discovered under lakes or across the sea much like the Irish Otherworlds of Tir Na NÓg — ’the land of the ever young’ or Tir Tairngire ’the land of promise’. Annwfn like the other Celtic spirit realms can also be entered quite by mistake or of a sudden while living in the mortal world, when the two seem to blur into one another and suddenly the hero of the tale has crossed over into something else entirely; the shift first becoming apparent by encountering one of its inhabitants — such as in the tale of Pwyll encountering the Cŵn Annwfn, the otherworldly hounds while out hunting, in the first branch of the Mabinogion. In this tale Annwfn can be found within the mortal Welsh realm of Dyfed, and in other parts of the Mabinogion, Annwfn can be found in the real-world locations of Harlech and on the island of Grassholm in Pembrokeshire, whereas in the Arthurian poem Preiddeu Annwfn or ’the spoils of Annwfn’ by Taliesin, Annwfn is located on an island across the sea.

Preiddeu Annwfn/The spoils of Annwn3

I praise the lord, ruler of a king’s realm

Who has extended his dominion over the shore of the world.

Well prepared was Gweir’s prison in Caer Sidi

During the time of Pwyll and Pryderi.

No one went there before him.

The heavy blue grey chain held the faithful servant,

And before the spoils of Annwfn he sings in woe,

And our bardic invocation shall continue until doom.

Three times the fill of Prydwen we went into it;

Except seven, none returned from Caer Sidi.

I am fair in fame if my song is heard

In Caer Pedryfan, with its four sides revolving;

My poetry from the cauldron was uttered,

Ignited by the breath of nine maidens.

The cauldron of the chief of Annwfn, was sought

With its dark rim and pearls.

It does not boil the coward’s portion, it is not its destiny.

A shining sword was thrust into it,

And it was left behind in Lleminog’s hand.

And before the door of hell’s gate, lamps burned.

And when we went with Arthur, glorious in misfortune,

Except seven, none returned from Caer Vedwyd.

I am fair in fame: my songs are heard

In Caer Pedryfan, Isle of the strong shining door

Fresh water and jet run together;

Bright wine their drink before their retinue.

Three times the fill of Prydwen we went by sea:

Except seven, none returned from Caer Rigor.

I set no value on insignificant men concerned with scripture,

They did not see the valour of Arthur beyond Caer Wydyr:

Six thousand men stood upon the wall.

It was hard to speak with their sentinel.

Three times the fill of Prydwen went with Arthur

Except seven, none returned from Caer Golud.

I set no value on insignificant men with their trailing robes

They do not know what was created on what day.

When at mid-day Cwy was born.

Or who made the one who did not go to the meadows of Defwy;

They do not know the Brindled ox or his yoke

With seven score links on his collar.

And when we went with Arthur, dolorous journey

Except seven none returned from Caer Vandwy.

I set no value on insignificant men with weak wills,

Who do not know on what day the chief was created,

When at mid-day the ruler was born,

What animal they keep with his silver head.

When we went with Arthur, piteous battle

Except seven none returned from Caer Ochren.

Congregating monks howl like a choir of dogs

From a clash with the lords who know

Whether the wind has one course, whether the sea is all one,

Whether the fire is all one spark of fierce tumult?

Monks congregate like wolves

From a clash with lords who know.

The monks do not know how the light and dark divide,

Nor the winds course, or the storm,

The place where it ravages, the place it strikes,

How many saints are in the Otherworld, how many on earth?

I praise the lord, the great chief:

May I not endure sadness: Christ will reward me.

This poem attributed to the bard Taliesin, and possibly written or at least composed as early as the eighth century CE, before finally being recorded in the fourteenth-century Book of Taliesin, recounts a raid on the underworld Annwfn by King Arthur in order, presumably, to steal the cauldron that resides there.

Many of the references in Preiddeu Annwfn are quite obscure, however, there are several aspects of the piece that relate to other remaining works and extend our knowledge of Annwfn. The raid itself is referred to as an aside in the Mabinogion tale of Culhwch and Olwen, where Arthur and his retinue sail across the sea to Ireland aboard his ship Prydwen to obtain the cauldron of Dirwrnach/Dyrnwch the Giant, which it was said would never boil the meat of a coward. Here the cauldron is seized and becomes one of the thirteen treasures of the Island of Britain although little more is known of it, including its location. In the poem, the raid is far less successful resulting in almost total death and destruction for Arthur and his men. A similar doomed voyage occurs when Bran the Blessed gives a life-restoring cauldron to his new brother-in-law Matholwch, but when Matholwch mistreats his sister Branwen, Bran is forced to rescue her and the cauldron is destroyed in the process. Just as in this poem, there are no survivors of the raid except seven men, including Taliesin and Pwyll and Rhiannon’s son, Pryderi. Taliesin’s connection to both tales and the same number of survivors show us this is the same tale recounted numerous times in different forms, and the cauldron itself is revealed very much as a central character in events rather than a mute object. Instead we may see that the Cauldron is in fact the sovereignty of the land, its heart and soul, the goddess incarnate, as embodied by Branwen, or Gwyn’s queen, Creiddylad — as discussed later — and sought after by numerous mortal world and Otherworldly forces.

The main reference to the attempted theft of the cauldron occurs in stanza 2, lines 8-9. “A shining sword was thrust into it/And it was left behind in Lleminog’s hand” remains ambiguous. It is taken by some to mean that that cauldron was stolen, or even broken by Lleminog — whose name means ’leaping one’ and is potentially either an epithet for Arthur, or a reference to the Irish god Lugh. Lugh or Lugus is thought to be the god of oaths, his name meaning ’to swear an oath’ although it is sometimes thought to also mean ’bright’ and ’shining’. It may be that it was left in the hand of Lugh as a matter of oath, or judgement of an oathbreaking after the attempted raid, like one of its Irish counterparts, the four-sided cup of truth that shatters when a lie is spoken over it, and reforms when a truth is said over the pieces.

However, when we consider the line “A shining sword was thrust into it” we see another possible meaning arise — that of a moment of conception — albeit in dramatic and even violent imagery, resulting in the attainment of the cauldron by Lleminog even if somewhat briefly. Given that the raid is disastrous and none survive ’except seven’ men it is far from given that they were successful in the theft, or even if that was the real aim. Although the theft is referred to in Culhwch and Olwen we must remember that the quest for the cauldron — for the soul and womb of the land — is a perennial quest of the spirit and not an historical account of a physical object. While the theme of its theft or shattering, like the loss of the grail, is a perennial symbol for the imperfect world and the wounded human condition, nonetheless it remains intact and whole for those who seek it in the heart of Annwfn itself — to either destroy or be renewed by, each in their turn and according to their nature.

Preiddeu Annwfn although Welsh in origin has much in common with the Irish Echtrai and later Immrama voyage tales which are of a similar age, and are also concerned with mortal adventures to Otherworldly destinations. Interestingly both the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland) which was compiled finally in the eleventh century and Nennius’s Historia Brittonum (ninth century CE) both discuss the Milesians, the ancestors to the Irish, encountering a glass fortress in the sea. Just as in Preiddeu Annwfn the inhabitants will not talk with them “It was hard to speak with their sentinel.” (stanza 5, line 4) and when the Milesians attack the majority of them are killed.

In the poem Preiddeu Annwfn, we see the otherworld of Annwfn given many titles, each describing its action or function, or perhaps even how Annwfn may be accessed. Let’s work through it stage by stage.

1) Caer Sidi — the fortress of the sidhe, or faery. Suggesting access to Annwfn may occur through encounters with faery. Transgressors or those chosen by the faeries and spirits may become imprisoned there. “well prepared was the prison of Gweir in Caer Sidi,” (stanza 1, line 3) Equally the faithful servant may be the initiate undergoing a period of ritual constraint or time held in the Otherworld.

2) “The heavy blue grey chain held the faithful servant,” (stanza 1, line 6) We also see here that Annwfn is accessed by going across water or across the sea, a recurring motif across Celtic literature. Equally this may represent a shift in consciousness, or emotional state, in Jungian terms accessing the collective unconscious or the shamanic state where all things become one.

3) “In Caer Pedryfan, with its four sides revolving,” (stanza 2, line 2) here we see the four-sided castle, or the castle with four revolutions. This bears a resemblance to the tower at Harlech where Bran the Blessed’s men were entertained by his head after his death, in a kind of mourning or holding zone. The four sides may refer to the four directions, or the turn of the seasonal wheel, suggesting perhaps that the task here is to gain knowledge of the seasons and the land on which you dwell in each direction until a sense of centredness and still presence is attained. Caer Pedryfan may also relate to the four-sided cup of truth, discussed above, which shatters if it hears a lie and comes together again when it hears a truth spoken over it.

4) “The cauldron of the chief of Annwfn,” (Stanza 2, line 5) Given further details in the poem, and surrounding lore we can see here that the chief of Annwn/Annwfn is in fact Gwyn, known here as Dyrnwch the Giant, just as he is known in the first branch of the Mabinogion as Arawn.

5) “Except seven, none returned from Caer Vedwyd.” (stanza 2, line 12) Caer Vedwyd is usually translated as the castle or fortress of the mead feast, that is, of feasting and celebration. Here we see a reference to an altered state of consciousness brought on by drink or other substances.

6) “Except seven, none returned from Caer Rigor,” (stanza 3, line 6) The fortress of stiffness or rigidity. Sometimes interpreted as the fortress of royalty though this is unlikely. The castle of rigor, as in rigor mortis, where the muscles in a dead body stiffen and become rigid. Here we see a reference to Annwfn as realm of the dead and the process of death and decay perhaps being an initiatory path after death, or re-enacted by the living via ritual burial or immersion in darkness, as is referred to in other works by Taliesin.

7) “They did not see the valour of Arthur beyond Caer Wydyr,” (stanza 4, line 2) Caer Wydyr, the glass castle, connected to Avalon and Glastonbury and the last destination of Arthur. The poem suggests that only in Caer Wydyr where the raid took place was it witnessed, but also that only at Caer Wydyr could such things be seen — such ambiguity and multiplicity of meaning is a common feature of Bardic material. Access to Annwfn and its wisdom via Caer Wydyr is perhaps accessed by observation of the stellar realm and perhaps also through scrying — literally looking through the glass.

8) “Except seven, none returned from Caer Golud.” (stanza 4, line 6) The fortress or castle of impediment, here we see Annwfn once more associated with the realm of the dead and the physical restraint and containment of an initiate. Another translation of Golud in modern Welsh is riches — the wealthy castle, the castle of riches, the castle of treasure. Sometimes translated as the gloomy castle suggesting its position between the night and day — a place in eternal twilight, or accessed through those liminal times such as dawn and dusk, life and death, although this translation is less reliable.

9) “Except seven, none returned from Caer Vandwy.” (stanza 5 line 8) The high fortress, the castle of the gods’ peak. Access to Annwfn and its wisdom has traditionally been gained by time spent in lonely remote places, especially the tops of mountains, such as on Cader Idris. Caer Vandwy is the same as that mentioned in the dialogue of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir — discussed later — where Gwyn saw battle and conflict, presumably on the defending side of this raid against Arthur and his men.

10) “Except seven, none returned from Caer Ochren.” (stanza 6, line 6) translations of Ochren are scarce and debated, but leading contenders are angular, or enclosed, possibly or “castle of the angular or shelving sides” e.g., a terraced slope. Given Annwfn’s position surrounded by water this could be a reference to the tide line, the liminal place between the land and the sea. Such places are always considered highly magical, allowing the seeker to slip through the veil, being neither this nor that. Alternatively, this could be a reference to a terraced hill fort, or other high hill such as the terraces on the sides of Glastonbury Tor. In this context, we are looking at accessing Annwfn via ancestral contact on the land or entrance into the faery hollow hills once again.

11) The poem ends with the poet criticizing the monks who have by the time of writing converted the population and largely forgotten the old gods and the vast bodies of lore attached to them, as well as basing their own knowledge on their superiors rather than feeling or experiencing their own faith, in direct comparison to the state of all knowing attained and displayed by the poet (Taliesin) himself. Despite this the poet hedges his bets and seems to reconcile himself to the new faith. “I praise the lord, the great chief: May I not endure sadness: Christ will reward me” (stanza 7, lines 11-12). It should be noted, however, that while the poet mentions Christ this once, the lord and chief referred to may just as easily be the chief of Annwfn as the Christian god.

In conclusion, we therefore know Annwfn by several names each providing clues to gain access to the otherworldly realm and a traditional initiatory path.

Caer Sidi — Castle of the Sidhe/faeries. By connection with Faery and the fair folk, and entering the Faery realm. Usually this is down to them approaching the seeker, but with time spent in nature and offerings made to befriend them, greater contact is always possible.

Caer Pedryfan — The revolving castle. By becoming mindful and still whilst observing at length the turn of the seasons. By becoming closer to nature.

Caer Vedwyd — Castle of the mead feast. By celebration and carousal, by the ingestion of consciousness-altering substances.

Caer Rigor — Castle of stiffness/rigidity. By death or attaining a period of death-like restraint and containment, such as ritual burial or enclosure in darkened spaces.

Caer Wydyr — Castle of glass. By extended periods of astrological and stellar study and meditation upon the stellar realm.

Caer Golud — Castle of impediment. By death and constraint — again either in the earth or sacred darkness. Also, possibly illness, grief, depression and mental illness.

Caer Vandwy — The high castle, castle of the mountain peak/gods’ peak. By meditation and observance at high places, especially mountain tops, which was a traditional bardic initiation and practice, such as spending the night or a prolonged period on Cader Idris.

Caer Ochren — Castle of the angular or shelving sides. By working in inner vision on the tide line on the sea shore, or by entering the faery mounds and terraced ancestral hillforts.

Practice: Cauldron scrying

In this exercise, we will seek self-knowledge, and Awen — vision and inspiration from the great cauldron via scrying — a divination technique using water and, optionally, sacred herbs.

Seek out some fresh mugwort Artemisia vulgaris (a traditional druidic plant for scrying and seeking vision) if you can, to burn as an offering when dried. Alternatively, you may steep some in oil for one whole month from dark moon to dark moon, before straining and storing in a dark glass bottle. Use the oil to anoint your brow and add a few drops upon the water when seeking vision.

You may also wish to gather some pebbles of jet, as mentioned in Preiddeu Annwfn to place in the water to aid you. Jet is traditionally used to help heal grief, and to grant protection — both suitable properties for a sacred stone associated with Annwfn, and found in the waters which separate the worlds. “Fresh water and jet run together” (Preiddeu Annwfn stanza 3, line 3).

Wait for dusk or darkness, and take a traditional black iron cauldron, or a dark-coloured bowl and fill with fresh water — from a natural spring or river for preference although cold tap water will do. Place in it the jet stones if you have them, and/or 3 drops of oil.

Seat yourself somewhere quiet — at the edge of trees or by the fireside are good places between the worlds. Breathe slowly and sit quietly, gently resting your eyes upon the surface of the water, and softly, under your breath, ask the waters of the cauldron to grant you wisdom if it will. Then leaning forward over the surface of the water, breathe gently upon its surface before sitting back, still resting your eyes gently upon the water.

Wait, in quiet stillness, for the visions to appear, in your inner vision or before you, according to your own gifts and nature.

When you are finished thank the water and the spirit of the cauldron, and pour the water upon the land at the foot of a tree or some precious plant, to return to the earth.

The Tylwyth Teg

The Fairy Glen above Bettws y Coed is called in Welsh Ffos ’Noddyn, ’the Sink of the Abyss’; but Mr. Gethin Jones told me that it was also called Glyn y Tylwyth Teg, which is very probable, as some such a designation is required to account for the English name, the Fairy Glen.’ People on the Capel Garmon side used to see the Tylwyth playing there, and descending into the Ffos or Glen gently and lightly without occasioning themselves the least harm. The Fairy Glen was, doubtless, supposed to contain an entrance to the world below. This reminds one of the name of the pretty hollow running inland from the railway station at Bangor. Why should it be called Nant Uffern, or ’The Hollow of Hell’? Can it be that there was a supposed entrance to the fairy world somewhere there? In any case, I am quite certain that Welsh place-names involve allusions to the fairies much oftener than has been hitherto supposed; and I should be inclined to cite, as a further example, Moel Eilio, or Moel Ellian, from the personal name Eilian, to be mentioned presently. Moel Eilian is a mountain under which the fairies were supposed to have great stores of treasure. But to return to Mr. Gethin Jones, I had almost forgotten that I have another instance of his in point. He showed me a passage in a paper which he wrote in Welsh some time ago on the antiquities of Yspyty Ifan. He says that where the Serw joins the Conwy there is a cave, to which tradition asserts that a harpist was once allured by the Tylwyth Teg. He was, of course, not seen afterwards, but the echo of the music made by him and them on their harps is still to be heard a little lower down, under the field called to this day Gweirglodd y Telynorion, ’The Harpers’ Meadow’.

John Rhys Celtic Folklore — Welsh and Manx, (1901, pp. 205-6)

A generic name for Welsh faeries, the Tylwyth Teg of ’fair folk’ are most often said to be under the rulership of Gwyn and to live in the lakes and mountains of Dyfed, but are also said to enjoy visiting the markets and fishing towns, and may appear much like humans other than perhaps an excessive love of music and dancing. In folklore, they are portrayed as keen on visiting farmers’ wives and being friendly to the peasantry overall although they should always be treated with respect and care, leaving them offerings of milk, cheese or butter. The Tylwyth Teg were often said to sweep the hearth or do other small tasks about the home, and were keen on bringing luck and love to those they liked, although conversely, they were often accused of stealing children (this seems to be a later addition). Tales abound of them seen dancing upon the hillsides in great numbers. ’Their music exercised an uncanny fascination. They lured young people into their circles to join them in the dance, and it was a task both difficult and dangerous to rescue these from their enchantments.’4

These Faeries are also said to be particularly fond of the hunt and ride on grey or white horses, in great processions rather like the Scottish Faery ’rades’ or rides.

The Gwragedd Annwfn

The Gwragedd Annwfn, or ’the wives of Annwfn’ are a race of female water spirits connected to rivers and lakes, especially in the mountainous regions of Wales, although tales of them can be found all over. They are said to live beneath the water, or access their kingdom by travelling through it, and all of them are under the rulership of Gwyn ap Nudd. Often, they are said to live in submerged towns whose ghostly faery bells can still be heard on calm days. One such is Crumlyn or Crymlyn Lake near Briton Ferry in Neath, which was once said to contain a large faery palace. Another is the famous Llyn Barfog in Snowdonia, where the Gwragedd Annwfn are said to have been seen many times, gathering at dusk to drive their milk-white cows to feast on the grass near the water ’Clad all in green, accompanied by their milk white hounds’.5 The wives of Annwfn are often associated with magical faery cattle which yield the most and the richest milk, and seem to bestow great abundance and fertility on the land on which they roam. Faery cattle are reminiscent of the old Celtic cow goddesses, such as the Irish Boann ’white cow’ who is both the goddess of the river Boyne and the wife of Nechtan, another name for Nuada/Nodens/Nudd. Boann is associated with fertility and abundance, but also healing and spiritual mysteries and training. The Goddess Brigid is said to have been fed on the milk of faery cows, which bestowed upon her some of her powers, and is sometimes said to be the daughter of Boann for this reason.

The Gwragedd Annwfn also bestow healing magic with their presence, and one famous story centres upon Llyn y Fan Fach. In the twelfthcentury there was a family of renowned herbal physicians which traced their healing skills to their faery mother. Their father Rhiwallon was said to have been a poor farmer who carried away one of the Gwragedd Annwfn that used to emerge from the lake whilst he was grazing his flocks. The faery woman consented to marry him, so long as he should never strike her more than three times in all their years together. She brought with her seven cows, two oxen and one bull, and soon they were rich and prosperous and had three sons and a large herd. But one day, so the tale goes, the farmer tapped her three times upon the arm — other tales suggest he her struck three different times — and she left taking her cattle with her back into the lake never to be seen again by anyone but her sons to whom she left a box of her healing potions and the gift of faery healing. Soon ’The Physicians of the Myddfai’ were the most respected healers in the land, treating Rhys Gryg, Lord of Dynevor and son of the last native Prince of Wales. When they died they left a large compendium of their healing practice, which can still be accessed today, and a large monastic school of herbal medicine.

Practice: Faery offerings

Those that would be a faery friend should remember the old ways and take up the practice of making offerings. These aren’t to assuage negative beings or convince them to treat you well — rather they are gestures of good will and respect, given from the heart. A good faery friend will gain much more from the exchange than they ever need give in offering. All offerings should be biodegradable and leave no trace upon the land and be given as a kindness without expectations of reward. Traditional offerings of butter, milk and cream are good and will most likely be eaten by local wildlife if placed out on the land or in a container that will be collected the next day. Otherwise offerings of song and poetry are also worthy.

To make your offering first decide what offering would be best with generosity and good will in your heart, then find a place that is suitable. This can be in your garden, or on an indoor altar. Alternatively, this can be somewhere out in nature that feels particularly energetically active or beautiful to you. There are many natural features that are favourite faery places, such as natural springs and wells, oak and elder trees, natural caves as well as ancient sacred sites such as long or round barrows, but suitable places may be found anywhere on earth. Seek out the in-between places — the edge of the hearth, where a spring emerges from the earth or where the shadows meet the light of the sun, and seek out the quiet in-between times to make your gift — the dusk or the dawn, before the rain or as the clouds pass, and as the seasonal wheel turns on the traditional cross quarter days Calan Mai/Beltane and Calan Gaeaf/Samhain, as well as the old feasts of Calan Awst/Lughnasadh and Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau/Imbolc. How you give your offerings, what and where will depend on your personal preference and hopefully on your own intuition and experiences of spirit contact, but always take care to leave no litter and to clear any away from a site that you find. Let the shining ones guide you, and may your friendship grow strong.

Practice: Gwyn and the Faery court meditation

Celtic and Brythonic seers, bards and Awenyddion — those who seek the wisdom of the Awen — the divine inspiration that reveals the knowledge of all things — have always used their inner vision to encounter the realm of the gods. If we engage our imaginations on a deeper level, and shift our consciousness, they can serve as excellent translation devices between us and spirit, leading us along energetic pathways until we can gain our own way and connect directly. Start this meditation journey to seek Gwyn in your inner vision by creating a sacred space, in whichever way you choose; perhaps by casting a circle, or just lighting a candle, and taking three deep breaths to calm and centre yourself. In your own way call any guides or allies to you that you may choose to work with, even if you do not know them by name — ask for assistance from spirit and it shall come to you. And aloud or in your own mind, state your intention to encounter Gwyn ap Nudd the chief of Annwfn, lord of faery. Try this meditation in the wild lonely places of forest or hillside if you can, or beside a river, but wherever you do it, even at home, be sure the place will be peaceful so that your inner vision is not disturbed.

Feel your feet steady on the ground beneath you, and the breath slow and steady in your lungs. In your inner eye see your feet standing on soft earth, a beaten path across a grassy meadow. Ahead you see a vast green hill stretching up into the sky. Its sides are clothed with dense forest and the air above it shimmers with many colours as if bursts of magical fire are emanating from its summit.

You follow the path across the meadow and see it leads you into a gap in the trees. As soon as you step under the leafy canopy you sense a shift in atmosphere. This is a sacred place, it’s as if the trees hide something from sight, and you hear the sound of hooves on soft earth but see nothing. The path pale against the shadows of the trees upon the ground, guides you in a wide arc around the hill, and disappears out of sight in a large spiral. Concentrate on your footsteps, one step after another, and feel the cool air on your cheek and the silent presence of the trees all around.

Eventually your path grows steeper and rockier, and up ahead you see the path terminates not on the summit of the hill, but at a small cavern entrance in its side. A hawthorn tree curls around it and the air is filled with its heady perfume. At the foot of this tree you see a figure sits, calm and still. You cannot see their face, but your skin tingles at the feeling of power all around you in this quiet place.

Walk up to the figure by the entrance, and bow. Greet them politely. They stand and ask you your reason for being here. Answer them honestly, with the first words that arise from your heart. If the guardian is satisfied you may enter the cavern. Remember this is sacred ground, and with every step you draw closer to the heart of the earth. The guardian comes with you to assist with etiquette and can be called upon for advice and guidance to this realm should you need it.

Inside you see that you stand at the beginning of a tunnel. The walls are lined with crystal veins and shimmer in the light of torches. Down the tunnel you go, holding your intention clear in your heart to encounter the faery court.

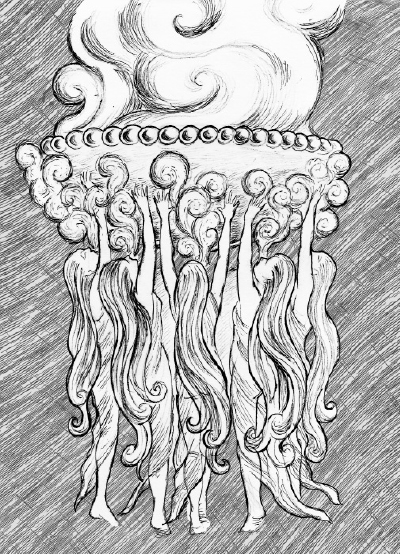

All at once the tunnel ends and you find yourself in a vast cavern lined with crystal and the deep roots of trees. A pool of water is fed from two small springs emerging from the rock. All around you is the faery host.

They take a myriad of forms, and some of them shift and change and shimmer as you look at them. They may take the forms of animals, trees, shadow and sparkling light, shifting in and out of humanoid form in the blink of an eye. Others are more settled and human in their appearance, regarding you with cool stern eyes, or even mockery. Others smile and greet you kindly. There are others there, ancient ancestors and faery travellers recently passed.

The guardian that has accompanied you leads you to the pool. Go to the water, and in your own way make a prayer to the old gods that you may find wisdom and kindness here. The guardian dips their fingers into the cool surface of the pool and anoints your eyes and your heart with its waters. Do not drink the water even if offered, but thank the guardian and the waters for their gift.

Look about the cavern now, with fresh, blessed eyes and heart.

Across the hall is a throne. Here sits a tall figure with long dark hair. Light radiates from him, dazzling and shimmering. He looks down upon you with bright eyes.

This is Gwyn, lord of Annwfn.

The guardian leads you to the throne. Greet the lord of this realm with a bow and your honest words. Take three deep breaths and try to hold your consciousness here for a while that you may receive his wisdom. Give this plenty of time.

After a while you may be led by the guardian to other places in the hill, or to other features but this should not go on for too long. Soon it will be time to return the way you came and you can ask the guardian to take you back or they may do so anyway.

Return the way you came, up through the tunnel and along the spiral path through the trees. As you emerge from the forest, take a moment to be aware of the change of light and feel your breath in your chest. As you walk across the meadow feel your body more and more until you come to the edge of the meadow and return completely to the everyday world.

Open your eyes and breathe deeply, feeling the air in your lungs hold you to the present time and place. Wriggle your fingers and toes, stamp your feet and take your time to feel fully grounded. You may like to record your experiences in a journal or notebook.

Faeries and ancestors

The realm of faery is always closely connected to the realm of the dead, the two seeming almost indistinguishable in the traditional tales and oral lore. Many a weary traveller or gifted musician tricked or seduced into the faery mounds is said to have seen their dead relatives within their halls, and Annwfn is equally a realm of the ancestors as well as the ever living. This chimes well with the tradition of faery beings living within the hollow hills or barrow mounds of the Neolithic chambered cairns and ritual megalithic sites functioning both as energetic doorways and punctuation points on the landscape around which stories may congregate in the memory of the local inhabitants. Gwyn ap Nudd’s dual role as both guardian of Annwfn and leader of the wild hunt as well as King of Faery illustrate this relationship perfectly. According to Crofton Crocker in 1825, one of his titles was ’lord of the cairn’ showing that the connection between these sites and the later faery lore was well established and surviving into the nineteenth century.

Gwyn ap Nudd budd buddinawr

Cynt i syrthiai cadoedd rhag Carneddawr

Dy fraiche no brwyn briw i lawr!

Gwyn ap Nudd! Victorious warrior!

How fell the hosts before the dweller of the cairn!

Thy arm like rushes hew’d them down!”6