Pagan Portals - Guided Visualisations: Pathways into Wisdom and Witchcraft - Lucya Starza 2020

Gwyn ap Nudd – White Son of Mist

The heathy headland of the family of Gwyn

It is often speckled smoke:

The rising vapour which surrounds the woods of May.

Unsightly fog wherein the dogs are barking,

Ointment of the witches of Annwfn.

Dafydd ap Gwilym ’The Mist’/’Y Niwl’ (fourteenth century)

Gwyn ap Nudd, guardian of Annwfn the Brythonic underworld and king of the Tylwyth Teg, the Welsh faeries, has long captured the imagination of poets and artists, from the ancient bardic tradition to modern-day fantasy writers. An ancient god of the Britons he has none the less survived the Christian period as a figure of both fear and longing, as a keeper of demons when the pagan Annwfn was transformed in the popular imagination into the Christian hell — and as a figure of romance and faery glamour; a courtly ruler within his glass castle, a handsome faery lover with his many courts within the hollow hills and barrow mounds of Wales and Western England, a horned warrior god, antler crowned, fierce spirit of the wild, and Winter king, the Brenin Llwyd — the grey king in the mist — aloof and unknowable. Accompanied by his faery hounds the Cŵn Annwfn he leads the dead to the realms beyond as lord of the wild hunt, soaring over the wild Welsh hills on faery rades (rides) with storm clouds in his wake, and as guardian of Annwfn he facilitates our transformation after death as we return once more to the great cauldron within the land. As faery lord of the forest, he is found in the wild places and on the hills and mountains, cloaking them with mist … tempting lovers and inspiring bards and visionaries who to this day will seek out solitary retreat in such places to undergo his initiations of the spirit, to return dead, mad … or a poet.

The name Gwyn is traditionally translated as ’White’, ’Fair’, ’Holy’ or ’Blessed’. Throughout the Celtic traditions we see the motif of something intrinsically good or spiritually enlightened being connected to the colour white, or literally emitting light or shining in some way. We could see this as describing someone as illuminated or radiant with some inner divine light or wisdom. This can be seen with the old Irish gods, the Tuatha de Danann, often called the ’Shining Ones’, and their later forms as beings of Faery or the Sidhe, are also described as luminescent in some way, implying a state of blessedness, radiating the light within the land. Gwyn’s Irish counterpart is Fionn Mac Cumhail, who also means ’Fair’, and who was spiritually illuminated by the Imbas — which equates with the Welsh Awen — poetic or oracular inspiration, and given magical powers of divination after consuming the salmon of knowledge. The Welsh Gwyn can be translated directly as Fionn in Gaelic, Find in Old Irish and Vindo in Gaulish, and has its roots the Proto-Indo-European ’weid’ “to see, to know”. It shares this linguistic root with the word druid, who has the knowledge, or the vision, of the dru — the oak. ’Weid’ is also the root of our English word wisdom.

The roots of Gwyn and Fionn lie in an early Celtic god Vindonnus — usually taken to mean ’white’ or ’clear light’. Vindonnus is usually taken to be a Gaulish aspect of the god Apollo, worshipped most notably in Burgundy, eastern France where a healing spring was dedicated to him. Apollo was both a Greek and Roman god and one with a complex set of attributes covering healing, prophecy, the poetic arts and music, as well as the sun and the light. His worship was widespread and he was particularly associated with oracles, his most famous being that at Delphi. Apollo was usually considered to be the Classical/Romano version of the Celtic god Belenus ’fair shining one’, who is associated like Apollo with the sun, but also with fire, as patron god of the Celtic festival every May 1st — Beltane ’the bright fire’. Some scholars cast doubt on Belenus’ and Apollo’s roles as sun gods, as their roles separate over time from purely solar functions, but as the overseer of Beltane, Belenus is not only a solar god, but one who oversees a rise in life force and fertility. His ’bright fire’ has as much to do with healing — traditionally the fires were used as much to banish illness as they were to celebrate a rise in vitality and fertility generally, and the light that he brings may equally be an inner illumination or surge in well-being. Academics consider Belenus Vindonnus to be especially concerned with healing eyes as many offerings found at his spring represented eyes, but the white or clear light he embodies could also be this inner illumination or inner vision, clear sight metaphorically as well as literally.

Ap or its earlier form Map, literally means son or son of and is cognate with the Scots Gaelic Mac.

Nudd (pronounced neeth) means mist in Welsh, but is also another name for a legendary Welsh hero Lludd LLaw Erient, Lludd or Nudd of the Silver hand. Nudd/Lludd was mentioned in the Welsh Triads as one of the three most generous men in Wales. However, his name also connects him to the Irish divine king Nuada, or Nuadu Airgetlám — ’Nuada of the silver hand’. Many early Welsh genealogies treat Nudd as an historical figure, but he is most likely derived from the early British god Nodens, whose worship appears to have similarities with or is the Brythonic equivalent of Nuada. His temple near Lydney, Gloucestershire suggests he was a god of healing and dream incubation, with connections to hunting and the sea. Those in need of healing or advice would make prayers and offer gifts to the god, before sleeping in special cubicles in the temple, in the hope of an oracular healing dream.

We can imagine Nudd/Nuada then to be a god of mist and cloud, but it seems unlikely that this is merely a god of misty or cloudy weather. Mist and fog are powerful symbols of transition and liminality in much Celtic literature, the legendary mists surrounding the Isle of Avalon being a prime example. To embark on any spiritual or healing journey we must encounter these liminal spaces, where the solid earth seems to melt and become indistinct, where our senses, our vision and direction may be clouded and confused for a while, where we must step forward bravely, trusting in our destination and our inner navigation to guide us. When we consider Nodens, this idea of liminality gains more traction in relation to healing dreams and sleep, where some sort of journey into the Other — or Inner worlds takes place. We get the sense that this is someone to do with a healing inner journey, changes of consciousness and seeking vision, wisdom and renewal, the Awen which may then be carried up into the everyday, waking world.

The name Nodens may come from several places, all of which are illuminating in connection with this discussion. The most popular root for the word amongst academics is probably the Celtic stem noudont or noudent, meaning to acquire, or have the use of, and earlier to catch or trap, as a hunter or fisherman, from the Proto-Indo-European neu-d meaning to acquire, or fish. At Lydney there were several statues of hunting dogs, which are traditionally connected with healing, but also to the gods of the hunt and the forest. There were also other artefacts such as bronze reliefs depicting a sea deity, fishermen and tritons. Perhaps it was believed that a healing sleep was a way to hunt a cure from across the waters of consciousness, or to fish one up from the depths of the Otherworld. Another suggestion has been that the name Nodens come from the Proto-Celtic sNowdo or sNoudo meaning mist or clouds, the ’sN’ being changed to N in the P-Celtic languages of Gaulish and Brythonic. This idea hits a problem with the fact that the sN still occurs in Old Irish which would therefore make it Snuada rather than Nuada. However, language is always a fluid thing over such large spans of time so there is still some potential for this argument and it is entirely possible the names Nudd, Nuada and Nodens developed from a combination of these roots. Nudd / Nuada/ Nodens might then be understood as some kind of hunter deity, a trapper of prey even, in the mist. We know him from his tales and his temple that he was a deity the sick or troubled came to for help, therefore we know he is a beneficent god, so a guide or ally perhaps in uncertain realms, in search perhaps of Gwyn, the illumination, the blessing, the inner radiance of the soul and healing remedy.

Practice: Seeking Gwyn ap Nudd

Seek out Gwyn whenever the wind blows; for in oral tales they say he and his people come on the wind … seek him when you see the mist gathering on the hills and valleys, at dusk or dawn, the thin doorways of the day between the realms above the realm within. Seek him in the reflections of starlight upon deep still water, and when you hear an owl screech in the night, or see the geese fly overhead on winter evenings … know that he is close. Close your eyes and feel the air on your skin, the promise of things unseen just a breath away.

Wander into the wild, the edges of the waters, the green and hidden places and the high hills. Find your voice in the still places when you are alone, and give him gifts of song and poetry, gifts of remembered tales and twining rhyme, carrying your heart with them — uttered in a whisper on the breeze or a shout upon the storm. Give him the truth of you, share with him your fierce spirit and your tears and know no shame, for at the end of it all when you time is done he will come for you still, better as a friend than a stranger.

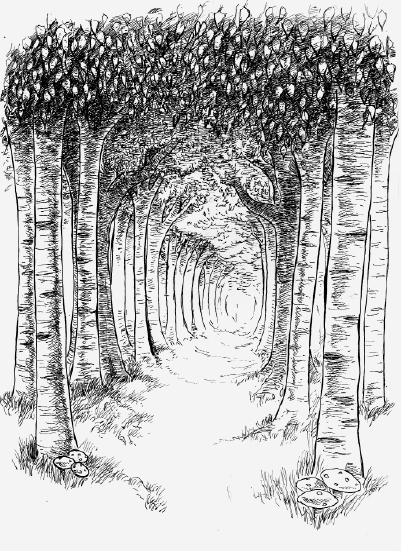

Practice: Entering the Forest

Awenyddion- those inspired by the Awen, bards and wise women would always honour the spirits and seek permission when entering the wild places on the land for wisdom and communion. A traditional prayer to Gwyn at such times was this:

ad regem Eumenidium et reginam eius: Gwynn ap Nwdd qui es ultra in silvis pro amore concubine tue permitte nos venire domum (14th Century.)

To the King of the Spirits and his queen: Gwyn ap Nudd, you who are yonder in the forest, for the love of your mate, permit me to enter your dwelling.1

Go to the wild places, go to the places where the deep green of trees and the rushing rivers surround you and the modern world is held at bay. Let nature be your greatest guide when seeking the old gods, especially Gwyn. When you get out into nature of any kind, try this exercise:

Close your eyes and take three steadying deep breaths. Try to quiet your mind as much as possible and just listen. What can you hear? Are there birds in the trees? Insects? A breeze ruffling the leaves? Try for a moment to open your heart up to the spirit of this place, its essence and atmosphere, try to sense it as a living being in its own right.

Now call out to Gwyn as Lord of the Forest, in your own way, or you may like to use these traditional words quoted above.

Tune in to your heart and the feeling in your belly — do you feel you are welcome to proceed? You may be fortunate enough to hear or see Gwyn’s reply, in a flash of vision or a single word in your ear perhaps — but more often than not it is tuning in to these finer senses within us that can teach us the most — where our brain cannot interfere. How do you feel?

If you feel you can proceed, focus a moment on your feet and the ground beneath you, the path stretching ahead of you through the trees. Now slowly put one foot in front of the other and walk along the path, calm and present to this sacred place where the worlds meet.

Breathe in the air — what can you smell? The green forest smell of leaves and rich earth? The dank but good smell of leaf mould? As you walk, call up the energy from the land, let every footfall be a prayer to call it in, to connect with its unique spirit and breathe it into your being. With each step fill yourself with the wild green energy of the forest.

Let your feet lead you, finding your way through the trees until you come to a place that feels as if it has a special atmosphere. It may be a large ancient tree, an open clearing, a burrow opening or the bowl-shaped shelter formed by an uprooted tree, the roots torn from the earth making a thick wall around you. When you find a place that seems to have a special resonance, sit down and make yourself comfortable, let your bones and muscles relax into the earth, into the wood and stone.

Continue to breathe in the energy of the forest, of the green world, and gently extend your senses all around you; the branches overhead, the roots below. Try to sense all the life that surrounds you. With every out breath stretch out your connection, and with every in breath breathe in more of the life force that surrounds you.

As you look around you, hold in your awareness that you are surrounded by spirits, that every tree, plant, insect, animal, fungi, breath of wind, drop of rain, cloud overhead is a sentient being, a spirit, a soul in its own right.

Here you will find, if you are patient, the secret ones, the Tylwyth Teg, the faery folk and the Lord of the forest himself, but give it time, and return often. Let the magic of the forest seep into your heart and soul.