Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies - Nigel Pennick 2015

Astronomy and the Winds

In the previous chapter the natural division of the earth into four directions and four quarters was based upon the perceived rotation of the heavens and the positions of sun- and moonrises. The various sorts of calendars were and can be regulated by solar and lunar phenomena without recourse to observing the stars. However, there is a star that stays close to the hub of the Northern Hemisphere night sky as it appears to circle during the night. In modern astronomy this star is called Polaris (Stella Polaris, the Pole Star or North Star). This star is an important marker in traditional navigation, both at sea and on land. It is a symbol of constancy and reliability, the unwavering guiding light, which leads us unfailingly to our destination. The mariners’ use of the North Star has given it many names: Tir, Stella Maris, the Lode Star, Leitstern, the Nave, the Leading Light, and the Nail. The latter name likens the star to a nail, around which the heavens rotate like the hub of a wheel. This star, which in the last millennia has appeared to stand above the terrestrial pole, was a guiding light for those navigating at sea and on land. The Old English Rune Poem tells of it as Tír, “which keeps faith well, always on course in the dark of night.” Its official astronomical name is Polaris, and a Medieval Latin epithet for it is “Stella non erratica,” “the unerring star,” and as an emblem it has the motto, “qui me non aspicet errat”: “He who does not look at me goes astray.”

STARS, ASTERISMS, AND CONSTELLATIONS

The names of the asterisms and constellations of the night sky demonstrate a particular worldview, and in northern Europe the etymology of the word “star” relates to “the scattered, strewn” (Reuter 1985, 19). Some Norse and some Welsh constellations are named after mythological objects. The varied names give us an insight into the worldview of people in the past, and the interweaving of the characters of folktales with the everyday world. In recent years many people have attempted to “reconstruct” a northern astronomy as it may have existed in Viking times. The old names of some stars are recorded. Sometimes, too, speculative names from Norse mythology have been attached to constellations of Graeco-Arabic astronomy, which are thought provoking. However, surviving traditional names of asterisms from northern Europe show that at least some of them do not correspond with the classical constellations, which, although they have a venerable history, are essentially arbitrary concepts.

Traditionally, the North Star (Stella Polaris) is bound up with the lore of the asterism close to it, the constellation called “Ursa Major” (the Great Bear) in modern astronomy, which is used as a means of finding it. Like the North Star, the Great Bear has numerous names in traditional northern European astronomy. The North Star can be located in the night sky by following the pointer stars of the constellation of Ursa Major, known by their Arabic names, Merak and Dubhe. The arrangement of the stars of Ursa Major has been likened to a plough or a wagon in various traditions. In Germanic astronomy the constellation was called either Woden’s Wagon or Charles’s Wain (Reuter 1985, 19). Traditional Welsh astronomy, recorded in Robert Roberts’s Arweiniad i Wybodaeth o Seryddiaeth (A Guide to a Knowledge of Astronomy; 1816), calls the asterism Saith Seren Y Gogledd (the Seven Stars of the North) by similar names: Men Carl, Men Charles (Charles’s Wagon), or Jac a’ i Wagen (Jack and his Wagon). Sometimes in Welsh the name of the Great Bear is translated literally: Yr Arth Fawr.

Another common traditional name for Ursa Major is the “Plough”; in Welsh Yr Aradr (the Plough) or Yr Haeddel Fawr (the Great Plough Handle); correspondingly, the constellation Ursa Minor is Yr Haeddel Fach (the Little Plough Handle). As well as Charles and Jac in their wagons, Peter holds the plough. In Scots a name for Ursa Major is Peter’s Pleugh (Warrack 1988 [1911], 409). Yet other Welsh names of this constellation are Llun Y Llong (the Image of the Ship); Y Sospan (the Saucepan/Dipper). In the English tradition, Charles’s Wain/the Plough and the Pleiades are confusingly both called the Seven Stars; as also in Welsh where Saith Seren Y Gogled (the Seven Stars of the North; Ursa Major) are distinguished from Saith Seren Siriol (the Seven Cheerful Stars; the Pleiades). According to Finn Magnussen (1845), the Pleiades were known in winter in Iceland as the Star. This asterism was used at night to tell the time, by noting the compass direction over which the Star was standing, or by its relationship to the landscape tide-markers (Reuter 1934, 185). According to eastern English traditional horsemanry, the seven nails in the horseshoe symbolize the seven stars of the Plough (Tony Harvey, personal communication).

The “belt” of the constellation Orion is a prominent feature in the night sky, being three bright stars apparently forming a line, and notable as a seasonal and nighttime marker. By its early rising, it signified the beginning of the season of harvest (Reuter 1985, 13). In both Welsh and Scottish tradition, this has been named as a measuring rod. In England it was called the Tailor’s Yard Band and in Wales it is Llathen Teiliwr (the Tailor’s Yardstick), and in Scotland the King’s Ellwand or the Lady’s Ellwand (Sternberg 1851, 126; Warrack 1988 [1911], 157). (An ellwand is a measuring rod, a Scots Ell in length, 37.0958 inches.) The latter name dedicated to the Lady recalls the Scandinavian name of Orion’s Belt, Friggs Rocken (Frigga’s Distaff) (Reuter 1985, 19). Another Welsh name connecting it with Our Lady is Llathen Fair (Mary’s Yardstick). A Scottish name for the asterism is Peter’s Staff (Warrack 1988 [1911)], 409). This asterism attracted various other names in northern Europe: the Three Fishers, the Rake, the Three Reapers, and even the Plough (Reuter 1985, 19). Another Scottish asterism, the Ellwand of Stars, denotes three stars in the constellation Lyra (Warrack 1988 [1911], 157). Sirius, called the Dog Star in England and Scotland, was Loki’s Brand in Pagan Iceland (Reuter 1985, 19—20).

Several other Welsh constellation names come from mythic characters in the Mabinogi, including Llys Dôn (The Court of Dôn), Cassiopeia; Caer Arianrhod (Arianrhod’s Fortress), Corona Borealis; and Telyn Arthur (King Arthur’s Harp), Lyra. In the latter constellation, Welsh astronomy differs from the Scottish in expressing the asterism in a classical way as a musical instrument and not a measuring rod. In common with Greek mythology, Norse myth tells of features set in the sky by the gods as memorials of their deeds. Two asterisms are associated with body parts of giants: Aurvandil’s Toe and Thjassi’s Eyes. O. S. Reuter identifies Corona Borealis as the Old Norse constellation Orendil’s (Aurvandil’s) Toe. Snorri Sturluson’s manual for poets, Skáldskaparmál, tells how Thor was carrying the giant Aurvandil in a basket across the ice river Elivagar, and his toe stuck out and was frozen, so Thor broke it off and threw it into the sky, where it became a star. Another giant, Thjassi, was killed by the Æsir, and his eyes were set in the sky as a memorial (Reuter 1985, 19, 20; Jones 1991b, 16). The stars Castor and Pollux appear to be the best candidates for this asterism. T. C. Lethbridge notes an English folktale collected in Horsley, Gloucestershire, which tells how the giant Wandil stole springtime, and winter continued without end. The gods hunted him down, recovered springtime, and cast the giant into the sky as a punishment. His eyes are seen in the night sky as Castor and Pollux (Lethbridge 1957, 71; Jones 1991b, 16—17). The Milky Way is seen as a road in the sky: an old Germanic name is Iringsweg (Iring’s Way); English tradition calls it Ermine Street, a name of one of the Four Royal Roads of Britain. In Welsh traditional astronomy it is Llwybr y Gwynt (the Path of the Wind); it also has the mythological name Caer Gwdion (Gwydion’s Fortress).

THE FIFTEEN STARS

Although they are known as the Fifteen Stars, they consist of fourteen major stars and one asterism: Aldebaran, Algol, Algorab, Alphecca, Antares, Arcturus, Capella, Deneb Algedi, the Pleaides, Procyon, Regulus, Sirius, Spica, Stella Polaris, and Vega (Wega). Each of the fifteen stars expresses a particular astrological quality. Each star has a corresponding gemstone, stone, or mineral and is assigned a sigil. In astrology the given virtues of these fixed stars combine with the planets to produce harmful or benevolent outcomes. They are rarely used in modern astrology, yet in medieval times their significance was taken into account, their sigils used magically, and as visible stars they assisted orientation and navigation.

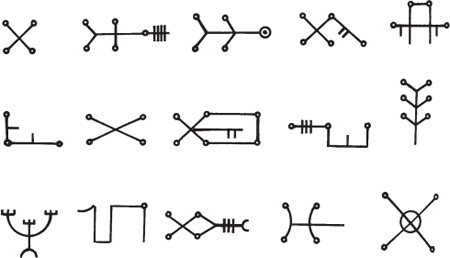

Fig. 4.1. Sigils of the fifteen stars. Top line, left to right: Aldebaran (the Follower); Algol (the Torch); Algorab (the Raven); Alphecca (Aurvandil’s toe); Antares (Fenris-wolf). Middle line: Arcturus (the Day Star); Capella (Goat star); Deneb Algedi (Goat’s tail); Pleiades; Polaris (Lode Star, the Nail). Lower line: Procyon (the Torch Bearer); Regulus (the Lord); Sirius (Loki’s Brand); Spica (the Sheaf); Vega (the South Star).

Aldebaran (α Tauri), the Bull’s Eye, is a red star that was one of the four Royal Stars of ancient Persia (with Regulus, Antares, and Fomalhaut). Astrologically, it was ascribed by Ptolemy to the nature of Mars. It rules over the red gem Carbuncle (Ruby). Algol (β Persei) is a white binary star traditionally malefic, bringing misfortune, violence, and destruction. Its nature is of Jupiter and Saturn. It is considered the most eminent of the stars, ruling over the Diamond. Algorab (δ Corvi) is another double star, purple and pale yellow. Like Algol, the Wing of the Crow, it is a malevolent star, of the nature of Mars and Saturn. Its stone is the Black Onyx. Alphecca (α Coronae Borealis) is a brilliant white star, signifying the knot of the ribbon of the Northern Crown. Its nature parallels Mars and Venus, bringing dignity and honor, artistic and poetic qualities. Alphecca’s stone is Topaz. Antares (α Scorpii) is a red and emerald green binary star. Its name means “rival of Mars,” and it marks the heart of the Scorpion. It is another malevolent power, bringing ruin and destruction through obstinacy. Its stones are Amethyst and Sardonyx. Arcturus (α Boötis) is a golden-yellow star also known as the “Bear Guard” (Arktouros). It partakes of the natures of Mars and Jupiter, or alternatively Mercury and Venus, bringing wealth, honors, and fame won by self-reliance. Its corresponding stone is Jasper.

Capella (α Aurigae), the Goat Star, is a white star, of the nature of Saturn and Jupiter. A beneficent star, its powers give honor, position, and wealth, and its correspondence is the Sapphire. Deneb Algedi (δ Capricorni), called the judicial point of the Goat (Capricorn), is an equivocal star, about whom various authorities differ widely, hence its attributions of beneficence and destructiveness, sorrow and happiness, life and death. Its planetary correspondences are Mercury and Saturn, and its gemstone is Chalcedony. The Pleiades are an asterism composed traditionally of the seven stars Alcyone, Calæno, Electra, Maia, Merope, Sterope, and Taygete. The position of the main star Alcyone is used in astrological calculations, and the Pleiades have the nature of the planet Mars and are considered to be disastrous, bringing illness, disaster, and death in conjunction with various planets. The Pleiades rule over the metal Quicksilver (Mercury). Procyon (α Canis Minoris) is a yellow and yellow-white binary star, called “before the dog” because in rising it precedes the Dog Star, Sirius. Its qualities are related to anger, carelessness, and violent activity; its planetary correspondences are Mercury and Mars, and its gem is Agate.

Regulus (α Leonis), the King’s Star, is a triple star, white and blue-white, also known as Cor Leonis (the Lion’s heart), one of the four Royal Stars of ancient Persian astronomy. Its powers are those of Jupiter and Mars, but it brings violence and temporary military success that ends in failure and death. Granite is the stone of Regulus. The Dog Star Sirius (α Canis Majoris) is a brilliant yellow and white binary star of the nature of Venus. It brings faithfulness, honor, and fame, and those born under its influence become custodians or guardians; its gem is Beryl. Spica or Arista (α Virginis), the Grain of Wheat, is a white binary star that partakes of the qualities of Venus allied with Mercury. Its gem is Emerald, and generally, it brings good fortune. Stella Polaris (α Ursa Minoris) is the North Star. It is a double star, pale white and topaz yellow. Its powers are those of Venus and Saturn, and astrologically Stella Polaris brings bad fortune. Its stone is the Lodestone, a natural magnet. This star will reach its nearest point to the true pole in 2095. Finally, Vega or Wega (α Lyrae) is a pale green star. An alternative name for this star is Vultur Cadens, the Falling Vulture. Its stone is Chrysolite, and the star’s influence is of the nature of Venus and Mercury. Vega will become the pole star around the year 13500 CE (Robson 1969, passim).

H. C. Agrippa lists the Fifteen Stars in order of their power and their rulerships, based upon their position in their constellations, beginning with Taurus. Their order is: (1) Algol, (2) the Pleiades, (3) Aldebaran, (4) Capella, (5) Sirius, (6) Procyon, (7) Regulus, (8) Stella Polaris, (9) Algorab, (10) Spica, (11) Alchamech (Acturus), (12) Elpheia (Alphecca), (13) Antares, (14) Vega, and (15) Deneb Algedi (Agrippa 1993 [1531], I, XXXII; II, XXXI). Names ascribed to some of them by Otto Sigfrid Reuter as existing in ancient Germanic astronomy are the Torch (Algol); Alphecca (in Corona Borealis, Aurvandil’s Toe); the Day Star (Arcturus); the South Star (Vega); the Torch Bearer (Procyon); Loki’s Brand (Sirius); and Thjassi’s Eyes (Castor and Pollux) (Reuter 1985, passim).

THE FOUR CORNERS OF THE HEAVENS

Although astrological charts are now drawn in a circle, in earlier times a square was used. The square was oriented “foursquare”; that is, with the sides running north-south and east-west. Square talismans are based on this principle, with their sides conceptually oriented in line with the four directions. In this system there are four corners at the intercardinal directions, giving a conceptual eightfold division. The quincunx, an important sigil in magic, is also arranged with four points in the corners of a square and another at the center. In northern household tradition the four corners of the building and those of each room are seen as places where either benevolent or malevolent sprites may dwell. During construction the corners are protected with offerings embedded in the fabric of the building, and when the building is in use, they are periodically reconsecrated with offerings of various kinds.

Medieval astrologers signified the four corners of the heavens as four progressive qualities: rising, midheaven (zenith), falling, and the lowest point (nadir). These correspond to the apparent places of the sun at sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight at the equinoxes (Agrippa 1993 [1531], II, VII). In northern cosmology the four corners of the heavens were supported by four dwarfs Norðri, Suðri, Austri, and Vestri, who are mentioned in the list of dwarfs in Gylfagynning. In European high magic the four corners were ruled over by the four archangels: Gabriel, north; Uriel (or Nariel), south; Michael, east; and Raphael, west. Some medieval churches, such as the former gate guardian St. Botolph’s in Cambridge, have guardian figures set at the four top corners of the tower.

The four corners of Iceland were supposed to have supernatural guardians. Sturluson tells a story of how the Danish king Harald Gormsson sent a magician to Iceland in the shape of a whale to report on the island. Along the north coast the magus perceived the land to be populated thickly with landvættir (land wights). At Vopnafjörður he tried to go ashore, but a dragon accompanied by other venomous beasts attacked him. On the south side he came to Eyjafjörður and was attacked by a giant bird. At Breiðafjörður, a monstrous bull accompanied by a band of hostile landvættir frightened off the magus. Then at Vikarsskeið another landing attempt was thwarted by a mountain giant wielding an iron staff. Apart from the dragon, the guardians closely resemble the evangelical beasts from Christian symbolism.

In Amsterdam in 1913 stone images of the four northern dwarfs were set in the ceiling of the main entrance of the shipping companies’ office called Het Scheepvaarthuis, a building that is an archetypal example of the Amsterdam School architectural style. Supporting the heavens, the dwarfs surround a metal image of the Great Bear with the stars, including the mariners’ guiding light, the North Star, represented by electric light bulbs (Boeterenbrood and Prang 1989, 101). The building is now an exclusive hotel.

THE EIGHT WINDS

Recorded wind lore from the north is far less coherent than in the Mediterranean mythos. However, a particular place is given as the origin of the winds: a remote island or dangerous, forbidden mountain. According to Roman tradition, the gods set Aeolus to rule the winds under the aegis of the goddess Juno. The winds were kept in caverns on the mountainous isle of Lipari and contained or released at will by Aeolus. In ancient Gaul (modern France), the god of the winds was Vintios, and the winds blew from his holy mountain, Mont Ventoux, in the south of modern France. Aeolus and Vintios were tutelary deities of all things connected with the wind. Sails, windmills, windvanes, weathercocks, washing lines, kites, illnesses carried by the wind, blown musical instruments, and the aeolian harp (whose strings produce harmonic modes) are all under the rulership of wind gods. Around 50 BCE the Macedonian architect Andronikos of Cyrrhus designed the octagonal Tower of the Winds at Athens, which still stands.

The classical tradition has four winds that correspond with the four cardinal directions: Boreas, Euros, Notos, and Zephyros. We receive from Andronikos the mainstream European tradition of the eight winds; the four preceding cardinal winds and four others located at the four corners of the heavens. The eight winds on the Tower of the Winds are, starting at the north and going sunwise, Boreas, Caecias, Apeliotes, Euros, Notos, Lips, Zephyros, and Skiron. These are known in medieval and later cartography, compasses, and maps by their Latin names, described by Vitruvius. The north wind is called Septentrio, the east wind is Solanus, the south wind is Auster, and the west wind is Favonius. The intercardinal winds are Aquilo, northeast; Eurus, southeast; Africus, southwest; and Caurus, northwest. These are the wind names that were adopted across northern Europe. The names of the winds are inappropriate as they are derived from specific qualities of winds perceived at Athens and later refined in southern Italy. The qualities of the classical winds cannot be meaningful outside the places where they were first recognized, yet they were used widely to define the compass rose. Even the Spanish imperial surveyors who laid out new towns in the Americas had the classical wind names on their plans. Old city plans from places as far apart as St. Petersburg, Edinburgh, Stockholm, Lisbon, Milan, and Mexico City show these eight winds. In 1992 at Cambridge University in England, the Maitland Robinson Library, a neoclassical building, was constructed at Downing College. Designed by Quinlan Terry, its octagonal upper section is a reworking of the Tower of Winds at Athens. It bears the names of the eight winds, carved in Greek characters. The classical eight winds are a very tenacious example of mythical continuity.

In practical terms the meanings of these eight winds are useless outside their area of origin. Those who used the wind for their livelihoods—sailors, windmillers, and traditional healers—always had their own names for local winds, which depended on where they were. There are a few records of local wind names in parts of Europe that actually refer to the local wind qualities. The traditional description of winds conserved in certain parts of France and Germany give an indication of how winds must have been perceived all over Europe in former times. In Provence and along the Côte d’Azur, la rose des vents (wind rose) is divided into thirty-two winds whose names vary from place to place and from season to season, and even according to strength. Winds recognized with the same name come from different directions in different places as local topography dictates. For example, on the coast at Nice the summer northeast wind Grégal has a different character in the autumn, when it is called Li Rispo. In winter, again it has a different quality, and it is called Orsuro. When it is gale force, the northeast wind at Nice is L’Aguielon. There, the south wind is generally called Marin (also Miejournau, Mijournari, or Miejour), but when it is soft and fresh, L’Embat, whilst in summer it is called Li Marinado. A notable wind recognized in la rose des vents painted inside Provençal windmills is called Ventouresco. It is a wind held to emanate from Mont Ventoux, the Celtic holy mountain of the winds, upon which Pagan pilgrims left small musical horns as votive offerings to the god.

In Germany, the Bavarian fishermen’s tradition of the lake called Ammersee has two parallel descriptors: one is direct descriptions, and the others are based on the places from which the winds are blowing. The principle of naming comes from desired directions of sailing, or from well-recognized places in the wind’s direction. The Ammersee is relatively small, so the wind names are less diverse than those of the Provençal winds. A northeasterly wind is called Vorderwind (front wind), a westerly is Hinterwind (back wind). Another name of the Hinterwind is Schwabenwind, blowing from Swabia, west of Bavaria. A Hochwind (high wind) is a southwesterly Wessobrunner Wind in the place-directional terminology. Winds from the south and southeast are called Sunnenwind, or the southeastern is called a Beuberger Wind after the place it comes from. A northerly is a Geradeheraufwind, otherwise a Donau, from the River Danube. A Querwind, otherwise a Zwerchwind (crosswind) is a northwesterly. In general, the widespread Latin names were used to mean particular directions on the magnetic compass rather than to denote actual air and weather qualities, as anyone who had to sail a ship or windmill was well aware.

The Icelandic magical talisman for navigation, called a Vegvisir (waymarker) in the Huld Manuscript, shows the eight directions denoted by different glyphs that may once have represented the sigils of the eight winds (Davíðsson 1903, pl. VI). According to renaissance writers on divinatory geomancy, the condition of the wind was taken into account before performing a divination. If it was unfavorable, the divination could not take place. Symbolically, the Irish bards assigned colors to the winds: the east was red; the south, white; the west, brown; and the north was black. Traditional medicine took note of the winds, for it was believed that certain winds at certain times brought illness and pestilence. The wind blowing at one’s birth also determined one’s future life, in complement to the influence of one’s natal horoscope. The first breath that a baby takes is the air from whichever wind is blowing at that moment, and this has a lifelong effect. In Wales on Teir nos ysbrydion, the “three spirit nights,” the wind blowing over the feet of corpses (the east wind) bears sighs to the homes of those doomed to die during the coming year (Puhvel 1976, 170).

In Scots tradition a red wind was an easterly to which plant blight was attributed. A traditional English adage says, “When the wind is in the east, it is neither good for man nor beast”; equivalent Scottish sayings are “When the wind is in the east, the fisher likes it least” and “When the smoke goes west [i.e., when the wind is coming from the east], good weather is past.” Another Scots adage tells us, “Everything looks large in an east wind,” referring to distant mountains. This one may well have its origin in the writings of Aristotle (Problems, 55): “In an east wind all visible things appear larger; in a west wind all sounds are more audible and travel further.” The influence of classical texts on folk sayings can never be discounted.

It appears that the effect of the wind indoors was taken into account in traditional society. The wind blowing at birth affected the life of every person, and the wind determined the onset and progress of certain illnesses. An indoor indicator, seemingly irrational, was used in Great Britain. There was a common belief that a dead kingfisher, suspended from a cord, would always turn its bill in the direction of the wind. This is alluded to by Christopher Marlow in his play The Jew of Malta (1633): “But how now stands the wind? Into what corner peers my halcyon’s bill?” The 1878 book English Folk-Lore records stuffed kingfishers hanging from the beams of cottage ceilings to act as weather vanes, “and though sheltered from the immediate influence of the wind, never failed to show every change by turning its beak to the quarter whence the wind blew” (Dyer 1878, 76).

WIND VANES, WEATHERCOCKS, AND WINDMILLS

Wind vanes are finely balanced artifacts that swivel on a fixed upright, driven by the prevailing currents of wind. The wind vane appears as the final rune of the first ætt in the Common Germanic Futhark. It is the rune wunjo (Old English wyn). It signifies the function of a wind vane that moves according to the winds, yet remains fixed in one place. Its reading is “joy,” obtained by having a stable base but being in harmony with the surrounding conditions. In the Viking Age, gilded metal weathervanes were mounted on ships, and similar ones were set up on stave churches in Norway. A golden wind vane was on the Mora, the flagship of William of Normandy, during his cross-channel voyage to invade England in 1066. A traditional motto depicted with a weathercock in seventeenth-century emblem books is, “Officium meum stabile agitare”: “It is my function to turn while remaining stable.”

Fig. 4.2. London St. Mary le Bow church dragon wind vane, designed by Edward Pearce, 1680. Drawing by Nigel Pennick, 2008

Structurally related to the wind vane is the vertical windmill, and millers had the most subtle appreciation on land of wind direction and speed. Dutch millers have names for the strongest winds measuring between 7 and 9 on the Beaufort Scale. Force 7—8 winds are called Blote bienen (bloody bees). All canvas must be taken from the sails when the wind is this strong. Force 8—9 winds are called Blote bienen en geknipte nagels (bloody bees and clipped nails), and a special canvas must be unfurled on the sails to slow them down, for the friction of runaway sails against the bearings runs the risk of fire and destruction of the mill. Although the Beaufort Scale was only devised in 1805, the use of specific names for wind speeds indicates an earlier origin. The craft of sailing windmills has been transmitted unbroken from master to apprentice from the twelfth century until the present day.

WIND MAGIC

There is a very ancient tradition that magicians have the ability to control the weather. H. C. Agrippa ascribed the supposed abilities to the wonderful power of enchantments. With a magical whispering, rivers could be turned back, the sea bound, and the winds controlled (Agrippa 1993 [1531], I, LXXII). These beliefs predated Agrippa by a long time, as he quoted Apuleius, Lucan, Virgil, and Ovid as his sources. In the north it was believed possible that the winds could be controlled by magic. Erik Edmundsson Väderhatt (“Weatherhat,” also called Eric of the Windy Hat; ca. 849—ca. 882) was a king of Sweden who was said to own a magic hat that he used to control the winds so his ship would always be able to sail where he wished. By turning his hat on his head toward the direction of a desired wind, it would start to blow. An illustration from Olaus Magnus (1655) shows the king on land, pointing to a ship, while crowned clouds are above, signifying his magical control of the weather. In northern seaports until the demise of sailing ships, sea witches sold ropes in which they claimed they had tied up the winds magically. Seamen who bought the charm received a rope tied with three knots. In the fifteenth century Ranulph Higden wrote that in the Isle of Man “is sortilege and witchcraft used; for women there sell to shipmen wynde [wind] as it were closed under three knottes of threde, so that the more wynde he would have the more knottes he must undo” (Moore 1891, 76). These magic ropes were considered proof against becoming becalmed. Undoing the first knot was supposed to provide a gentle wind. The second knot undone would yield a stiff wind, but the third knot released a gale. Labyrinths were also part of Scandinavian mariners’ wind magic, used to call up the wind in the Age of Sail. A Norwegian labyrinth called Truber Slot, beside Oslo Fjord, was activated magically to ensure favorable winds for sailing. The method was to walk to the center and back out again without stumbling. According to labyrinth researcher John Kraft, appeasement of the deity of the northwest wind was associated with labyrinth magic (Kraft 1986, 15).