Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies - Nigel Pennick 2015

Practical Magic: Patterns and Sigils

THRESHOLD AND HEARTHSTONE PATTERNS

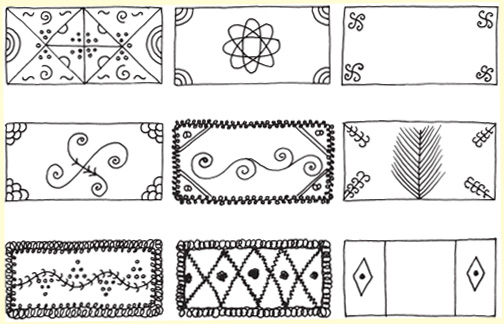

In parts of Great Britain was a custom of marking the threshold or hearth with knotlike patterns to bring good luck and ward off harm. The expert on traditional buildings Sidney R. Jones noted in 1912, “Villagers throughout the north of England make a practice of sanding the steps to doorways. It is an odd custom, many years old, which still survives. The stone step is run over with water, partly dried, and to the damp surface is applied dry sand or sandstone. Varied are the patterns that are worked on risers and treads” (Jones 1912, 114, 116). In various parts of England and Scotland where the practice survived long enough to be recorded, they were drawn with chalk, pipe clay, or sand (Canney 1926, 13). They were made every year on particular meaningful days. In Cambridge this was Foe-ing Out Day, March 1. Some are illustrated in figure 13.1.

There is a pattern seemingly local to the town of Cambridge, called the Cambridge Box. In Newmarket and Cambridge, a continuous loop pattern was also chalked around the edges of floors in stables and outhouses. Clearly an apotropaic pattern, it is called the “running eight.” This pattern had to be made in a single movement without stopping during the process. Ella Mary Leather describes threshold patterns of chalk in the English West Midlands villages of Weobley and Dilwyn: “The stone would be neatly bordered with white when washed, with a row of crosses within the border” (Leather 1912, 53).

Fig. 13.1. Threshold patterns from England and Scotland.

North of Herefordshire, in Shropshire, patterns were made by rubbing bunches of elder, dock, or oak leaves on the stone. In Eaton-under-Heywood in Shropshire, patterns were “laid” on thresholds, stone steps leading to bedrooms, and the hearthstone. Their function was to prevent the Devil from coming down the chimney (Dakers 1991, 169—70). Comparable to these temporary patterns are permanent flooring patterns made from traditional materials: bones, cobbles, bricks, and tiles, and in some places they are related to patterns in brickwork and clothing (Van der Klift-Tellegen 1987, 36—38). The patterns of traditional bit mats or rag rugs resemble those made in brickwork and drawn on hearthstones and thresholds. Patterns often have a diamond in the center, a border and triangles at the corner. Bit mats are made of recycled fabric from worn-out old clothes cut into strips and attached to a fabric base (Dixon 1981, 46—47).

Fig. 13.2. Threshold cross of pebbles, Welshpool, Wales.

THE BINDING OF LORD SOULIS

The story of Lord William Soulis contains many elements of traditional northern magic, and a border ballad composed by John Leyden preserved an older legend in rhyme. Hermitage Castle where Soulis lived was a key fortress on the borderlands of England and Scotland. According to the ballad, Soulis was a cruel and treacherous tyrant who oppressed his vassals and slaves as much as he did his enemies. But he was also a practitioner of magic who had a familiar sprite called Old Redcap. Redcap made Soulis magically wound-proof, so he could not be harmed by edged weapons, neither could he be bound by chain nor rope, but only by sand, which cannot be made into ropes:

While thou shalt live a charmed life,

And hold that life of me,

’Gainst lance and arrow, sword and knife,

I shall thy warrant be.

Nor forged steel, nor hempen band,

Shall e’er thy limbs confine,

Till threefold ropes of twisted sand

Around thy body twine

(HALL 1867, 147—48)

Soulis’s enemies finally ambushed him, but their weapons would not bite. But still they succeeded in forcing him to the ground. But when they bound him with ropes, they broke. Then they used chains, and these too would not hold. Only magical ropes could bind him, and the magic number nine appears in the formula. Sand was taken from the stream called Nine-Stane Burn. Nine handfuls of barley chaff were added and threefold plaited ropes made from it. The ropes of sand were contained inside tubes of lead, and it was these with which Soulis was bound. Then, wrapped in leaden bonds that disempowered his magic, he was thrown into a cauldron. They set it upon a fire at Nine Stane Rigg, the ridge separating Teviotdale and Liddesdale, on top of which was a megalithic circle of nine standing stones. Then Lord Soulis was boiled to death in the cauldron inside the circle.

STRAW BINDINGS, KNOTS, AND FIGURES

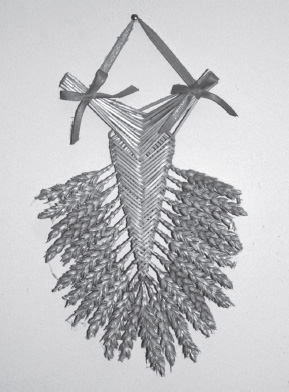

Straw, the by-product of grain farming, has many uses. Straw rope or netting was used in the western seaboard of Europe to tie down roof thatch, which itself is often made of straw. Traditional bee skeps are made from straw rope, in the form of a spirally wound dome, stitched together. Straw is also woven into hats and shoes, sometimes for temporary and ceremonial use (see Evans 1957, 278; Bärtsch 1998 [1933], 59—82). Special straw crosses are made in Ireland in celebration of St. Brigid’s Day (February 1). Straw plaits are most associated with the termination of the harvest, where making special items by plaiting straw was a common practice. In many parts of Europe, the final sheaf of corn to be cut was made into a humanoid figure that was carried ceremonially with the harvest being taken to the farmyard and took an honored place in the harvest feast that followed. An account of the harvest in Norfolk in August 1826 tells how “the last or ’horkey load’ . . . is decorated with flags and streamers, and sometimes a sort of kern baby is placed on the top at the front of the load” (Hone 1827, II, 1166). A visitor to the Cambridge Folk Museum in 1951 told the curator Enid Porter of a tradition from his grandmother’s early years in Litlington; how the farmer held up the last shock of corn, then one of the men made a humanoid figure with head, arms, and legs from it. At the horkey supper, the figure sat in a special chair during the feast. After the meal, it was set on top of the corner cupboard, in the holy corner (Porter 1969, 123).

Nowadays, the name “corn dolly” is used to describe any of the numerous forms of straw plaiting formerly connected with the harvest in Great Britain, whether humanoid or not. But the name “corn dolly” is of recent origin; the contemporary names of straw plaits when they were in use being “kirn maiden,” “kirn baby,” “neck,” “ben,” and “fan.”

The origin of “dolly” as their name comes from a meeting of the Folk-Lore Society in London, February 20, 1901, when “Mrs. Gomme exhibited and presented to the society a Kirn Maiden or Dolly, copied by Miss Swan from those made at Duns in Berwickshire” (Folk-Lore 12, 1, June 1901, 11, 129). In a letter to Gomme, Swan wrote: “I am sure that there was a good-luck superstition attached to the making and preserving of it, although it was not much talked about. The Kirn I sent you, though a modern dolly, is a faithful reproduction of those I have seen and helped to dress ’lang syne’” (Folk-Lore 12, 1, 215—16). The image that Mrs. Gomme showed the folklorists was not made from the last sheaf for the harvest but was a replica. Not being an actual Kirn Maiden used in harvest rites and ceremonies, it was called a dolly, just as a dolly represents a real baby but is not one. From the 1950s onward the generic name “dolly” became the norm. Like the name “witch posts,” it has no historic authenticity.

Fig. 13.3. Border Fan straw plait, Melverley, Shropshire, England.

In 1951 the organizers of the Festival of Britain in London commissioned masters of straw plaiting to make masterworks of the genre to celebrate the ancient craft. Old and new designs were put on show side by side; the Essex straw plaiter Fred Mizen made a straw lion and unicorn (Cooper 1994, 62), while Arthur “Badsey” Davis made a crown-shaped plait from forty-nine straws, a design now known as “Badsey’s Fountain” (Sandford 1983, 56). It is likely that this form originated as the crown of the hay rick (Lambert and Marx 1989, 88). Davis came from a Worcestershire family that had handed down the craft’s secrets through the male line for generations. George Ewart Evans notes a man from north Essex who made straw plaits at Blaxhall, Suffolk. He did not put them on the last load, but they were used in the church as decoration during the time of the Harvest Festival (Evans 1965, 214). Traditionally, straw plaiting was done by men until the 1951 Festival of Britain, when the Women’s Institute took it up. Now, mistakenly, it is seen as a traditional women’s craft, and some who make corn dollies throughout the year view their work as worship of the Goddess.

TRADITIONAL PATTERNS, SIGILS, AND GLYPHS

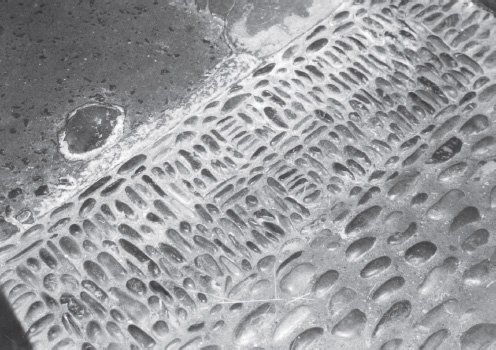

The skills of self-making are essential in traditional society. The rural poor, and those whose work was independent of masters, or in some way not allied to the urban collective—such as carters, drovers, boatmen, and fishermen and fishwives—retained personal craft skills that were downgraded in towns by the industrial revolution. Their home-crafted clothes, self-made tools, and utensils were often considered rustic or rural by urban dwellers and inferior to manufactured goods. Knitwear is strongly associated with the areas bordering the North Sea, where hardy sheep have been herded for thousands of years. The patterns on traditional woolen knitwear have customary meanings, containing a vast repertoire of symbolic patterns that vary from place to place. Embedded in traditional country and coastal crafts are techniques and patterns that go back perhaps thousands of years. In them the meaningful symbolism and magic of making and the artifacts made affirms the positive values of continuity and self-reliance. The individual designs on traditional fishermen’s knitwear from Scotland, England, and the Netherlands are assembled from a repertoire of symbolic patterns that include the cable, flag, tree of life, fishbone, waves, and lightning bolt or zigzag.

Each pattern has its own lore, some of it magical. The ing-runerelated pattern of five diamonds called “God’s Eye” in East Anglia has the same name in Dutch, Godsoog. A woman in IJmuiden told knitting researcher Henriette van der Klift-Tellegen that the Godsoog on the sweater looks after the seamen in strange ports, and also that the pattern enables men to find the front in the dark and put it on the right way round. In the Netherlands it is viewed as essentially an English pattern (van der Klift-Tellegen 1987, 19). On the east coast of Britain, the decline of the fishing industry in the late twentieth century broke up many of the communities that had sustained the knitting tradition. Those that still exist now continue as emblems of local identity. Various patterns from Amble, Cullercoats, Flamborough, Newbiggin, Patrington, Seahouses, Scarborough, Staithes, and Whitby are preserved, and new ganseys are knitted according to these traditions. Also extant are the jersey patterns of the Keel and Sloop men on the inland waterways around the River Humber, inland from Hull as far south as Lincoln and Nottingham. They include moss stitch, chevron, hexagram, diamond, tree of life, and chequers.

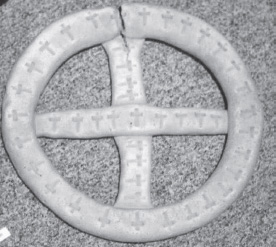

MAGIC IN MAKING EVERYDAY THINGS

There is no distinction between religion and magic in traditional societies. It is only a matter of semantics how we describe the saying of prayers, incantations, and making signs when something is done. There are many small acts taught as integral with making and doing, such as making the sign of a cross over food. In brewing and baking, for example, the sigil known as “two hearts and a crisscross” was traditionally used to protect the mash or dough. It is composed of two hearts with a cross in between. In 1895 F. T. Elworthy noted that an old man in Somerset had told him that in brewing, before the mash was covered up to ferment, the sigil was drawn to ward off the pixies (Elworthy 1895, 287).

Robert Herrick in his Hesperides (1648) alludes to this in a Charm:

This I’ ll tell ye by the way,

Maidens, when ye leavens lay,

Crosse your dow [dough], and your dispatch

Will be better for your batch.

(HERRICK 1902 [1648], 298)

In addition to the invoking of the intrinsic magical powers of the cross and the hearts, bakers used a pin to prick the emblem into biscuits, the “pricking” mentioned in the British nursery rhyme Pat-a-cake, Pat-acake, Baker’s Man.

Fig. 13.4. German ring bread with crosses.

ICELANDIC SIGIL MAGIC

Icelandic sigil magic is extant in medieval magical manuscripts such as the Hlíðarendabók, the Huld Manuscript, the Galdrabók, the Kreddur Manuscript, and a number of other original texts preserved in the National Library in Reykjavik. This sigil magic is not unique, as is often claimed, but part of the European mainstream magical use of seals, talismans, and magical warding signs. Sigils of similar form and construction appear in numerous mainland Euopean grimoires, including The Lesser Key of Solomon (see Waite, 1911; Mathers, MacGregor, and Crowley, 1997). But in Iceland the sigils appear to have been widespread in folk magic and, more importantly, were collected together and written down, so we have records of many sigils, along with their names and accompanying spells of empowerment. In classical European magic, such complex sigils represent and give access to particular spirits, which then are commanded to do the magician’s bidding. General warding signs and magical sigils not intended to invoke spirits are used in traditional trades and crafts. These are known in many other parts of Europe. In Icelandic sigil magic all human necessities are provided for.

The Ægishjálmur (“helm of awe,” cover or shield of terror), is the best known of all Icelandic magical sigils. Ruling over the eight directions, it is the sigil of comprehensive, irresistible power. Its function is to induce fear in one’s opponents, thereby dominating them. In the Nibelungenlied legend, the helm of awe was gained by Sigurd Fafnirsbane when he slew the dragon Fafnir. After Christianization, Sigurd was said to be one of the spectral riders in the Åsgårdsrei along with Thor, who had been relegated from the status of god to that of evil spirit. But the Ægishjálmur remained as a powerful magical sigil. Another Icelandic magical symbol, the Salomons Insigli (the “Sign of Salamon,” named for the Jewish king Solomon), does not refer to the common hexagram or pentagram, but rather to a sigil that is a form of the Ægishjálmur.

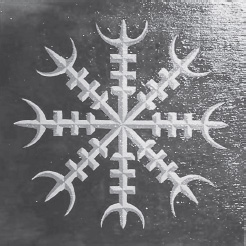

Fig. 13.5. Helm of Awe. Painting by Nigel Pennick, 1993

In Anglo-Norman heraldry, this sigil is the Escarbuncle, and in German heraldry, Glevenrad or Lilienstapel. Technically, the pattern arose in the armorers’ craft as a means of strengthening a shield (Fox-Davies 1925, 64, 290—91). The image of the Helm of Awe and the heraldic Escarbuncle and Glevenrad is that of a blinding light dazzling the onlooker. As its Anglo-Norman name tells us, the heraldic emblem represents the carbuncle, the fiery red gemstone that we call a ruby. The characteristic of the carbuncle was to shine in the dark “like a live coal,” for the Latin word carbunculus means “a little coal.” Albertus Magnus wrote that the carbuncle was ascribed the powers of all other gemstones (Albertus Magnus 1569, II, ii). It possessed a virtue against all airy and vaporous poisons (Agrippa 1993 [1531], I, XIII). The carbuncle is ruled magically by the red star Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus the bull. The Old French saga Le Pélérinage de Charlemagne (The Pilgrimage of Charlemagne) tells that Charlemagne’s bedchamber was reputed to be lit up by a carbuncle.

Charlemagne features as the emblem of power and stability in the Icelandic sigil called Karlamagnúsar Hringar (The Rings of Charlemagne). This sigil purports to represent nine rings of help sent by God with his angel to Pope Leo to be given to Charlemagne to protect him against his enemies. The Roman, Byzantine, Carolingian, and Ottonian emperors, as well as many early medieval kings, had their own monograms composed of the letters of their names (Weber 1940, 334—42). They may well have been tattooed upon slaves as a sign of ownership (Gustafson 2000, 17—31). It is possible that magicians used these emblems of imperial power as sigils in their magical operations. It is clearly part of mainland European magic connected with a strong Christian orientation. Charlemagne was the Holy Roman emperor who suppressed Paganism in Saxony and resisted Islamic invaders in France, so he was the epitome of a defender of the faith. Charlemagne’s sigil is threefold, three rings of three, and the accompanying spell is empowered by the three holy names: “In nomine Patris et Filio et Spiritu Sanctu Amen” [sic]. It is therefore a ninefold charm, composed of nine rings, each with a corresponding power. Nine is the ancient northern magic number, and although ascribed to Pope Leo and Charlemagne, the nine rings are redolent of the tale of Draupnir, “the dripper,” a magic artifact made by two dwarf artisans for Odin. Draupnir’s magic was that from it every ninth night, eight new rings dropped.

The first ring of Charlemagne protects against the wiles of the Devil, attacks by enemies, and troubles of the mind. The second ring prevents collapse of the will, fear, and sudden death. The third turns back the hatred of one’s enemies upon themselves so that they are fearful and retreat. The fourth ring is against wounds from swords; the fifth against being disorientated by magic and losing one’s way; while the sixth wards against persecution by powerful, evil men. The seventh circle brings triumph in legal disputes and general popularity; the eighth suppresses fear, and the ninth wards off all vices and debauchery. When expecting the enemy to come, these nine circles of Charlemagne are intended to be worn on the chest or on either side of the body. In its form, this sigil also resembles the seal of the evil spirit Forneus, a sea monster who teaches all arts and sciences and reconciles enemies (see Waite 1911, 204—5).

Fig. 13.6. Anglo-Saxon magic rings. Top: gold ring with runic magic inscription from Kingsmoor, Cumbria, England. Below: gold ring with sigils at each end, Peterborough, England. The Library of the European Tradition

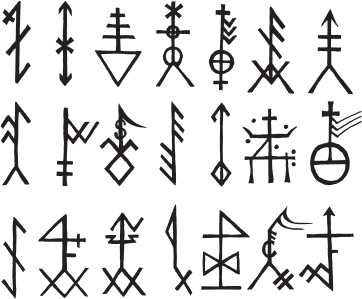

Icelandic magical staves protected against everyday problems: Kaupaloki helped merchants to close deals and enjoy prosperous businesses; Þjófastafur warded off thieves, or exposed their deeds; Angurgapi was carved on the ends of barrels to prevent leaking; Veiðistafur gave luck to fishermen; vegvísir helped mariners keep on course and ride out bad weather, while farmers used Tóustefna to keep foxes away. This was the magic used to get by in everyday life. Varnarstafur Valdemars, “Valdemar’s Protection Stave,” was used to augment the user’s status and happiness. Gambling and sporting contests are uncertain pastimes, and every culture has magical spells and practices to give the contestant an edge over the opposition. In 1905 Willard Fiske noted a charm: “If thou wishest to win at backgammon, take a raven’s heart, dry it in a spot on which the sun does not shine, crush it, then rub it on the dice.” Another talisman used a different part of a bird: “In order to win at kotra, take a tongue of a wagtail, and dry it in the sun; crush and mix it afterward with communion-wine, and apply it to the points of the dice, then you are sure of the game.” A kotruvers (spell) for winning at backgammon was recorded by Jón Arnason. It called upon the power of famous Norse kings. “The kotrumenn (backgammon players) should call ’Olave, Olave, Harold, Harold, Erik, Erik.’ The one wishing to win must write this formula in runes and either carry it somewhere on him, or let it lie under the backgammon board, on his knees, while he is playing. He must also recite the Lord’s prayer in honor of St. Olave, the king” (Fiske 1905, 346).

Contestants in glíma (wrestling) used the sigils Ginfaxi and Gapaldur. Written on parchment, Ginfaxi and Gapaldur were put in the wrestler’s shoes so they would operate during the bout. Ginfaxi was worn under the toes of the left foot, while Gapaldur was put beneath the heel of the right foot. Dunfaxi, carved on a piece of Oak, was used to win in legal cases. There were also magical sigils and formulae used to call up evil spirits and awaken draugr revenants (stafur til að vekja upp draug); ones against harmful magic (stafur gegn galdri); and ones using magic against other people, such as the fear-inducing Óttastafur; and Dreprún, the Death Rune, which is actually a sigil and not a rune (Davíðsson 1903, passim; Flowers 1989, 59—103). The housebreaking sigil and spell Lásabrjótur, the “lock-breaker” or “castle-breaker,” evoked the power of trolls to move the bolt inside the door, pulling it so the Devil’s squeak would be heard (the bolt sliding open). It was to be laid on the lock and breathed upon. One of the powers ascribed northern European folk magicians is the ability to get through locked doors. In East Anglia, eastern England, the adage “no door is ever closed to a toadman” expressed the belief that someone who possessed the toad bone had the power of invisibility and unauthorized entry.

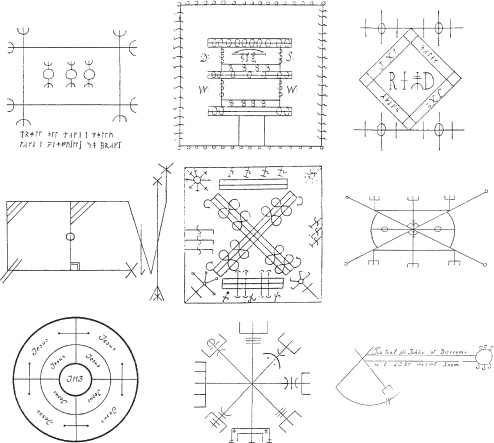

Fig. 13.7. Icelandic talismans and magical sigils from the Galdrabók, Huld Manuscript, and so forth. Left to right, top row: Lásabrótur, lockbreaker; Drottníngar signet, against all spirits; Jósúa insigli, protective power of Joshua. Middle row: Dreprún, livestock death sigil; Astros, disempowerment of detrimental runes (see British threshold patterns); Thjófastafir, thieves’ sigil. Lower row: Cross of Óláfr Tryggvason (ninefold names of Jesus), protective; Vegvísir, direction knowledge; Vatrahlífir, protection in water. The Library of the European Tradition

Fig. 13.8. Medieval housemarks and owners’ marks from eastern England, to identify property, but also with a magically protective function, many being derived from bind-runes.

LOTS

![]()

St. Peter’s game

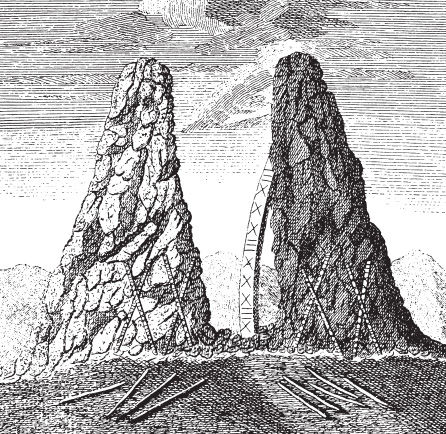

The interface of randomness and the determinate occurs in the throwing of dice. When a particular number turns up, it is a moment of irreversible change. War veterans often talk about a bullet “with your number on it” that inescapably dooms one to die. Numbers and counting appear to be embedded in the selection of sacrificial victims. In the fifth century CE, Sidonius Apollinaris noted the custom of Saxon pirates who sacrificed each tenth captive to the god of the sea as a thanksgiving for a successful voyage before setting sail for home (Dalton 1915, VIII, 6, II, 150). This is the Roman custom of decimation. The means of selection of victims for sacrifice is often described as “drawing lots,” but a number sequence recalled in Finnish and Swedish labyrinth traditions may be a surviving example of a particular means of selection. Two small rock-cut labyrinths on the island of Skarv in the Stockholm Archipelago, Sweden, are accompanied by a long rectangle in which the sequence is carved (Kern 1983, 411). This sequence is also known from runic calendars from Norway (Davis 1867, 472).

The number sequence is called St. Peter’s Game, Pietarinleikki (Finnish), Sankt Päders Lek (Swedish), or Sankt-Peters-Spiel (German). In ancient rock carvings, medieval clog almanacs, and primestaves this sequence is depicted as a series of crosses and uprights, drawn between two parallel lines. It is a method of dividing 30 into two equal parts, picking out every ninth one. This is the sequence XXXXIIIIIXXIXXXIXIIXXIIIXIIXXI (4, 5, 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 1, 2, 2, 1).

Fig. 13.9. Sámi world pillars with rods and Pietarinleikki. Eighteenthcentury engraving. The Library of the European Tradition

Hermann Kern states that this “game” is widespread in northern Europe and known as far back as the tenth century in Germany, where it was called Josephsspiel or Judenersäufespiel (Kern 1983, 411). According to the explanatory tale, a ship carrying Christians and Jews was overtaken by a storm that threatened to sink it. St. Peter was on board, and he resolved that it was necessary to throw half of the passengers overboard to save the rest. It was agreed that as there were thirty people on board, fifteen Jews and fifteen Christians, fifteen would have to die, and they would stand in line and every ninth one would be thrown overboard. St. Peter arranged them so Christians and Jews were in the sequence, then picked out every ninth person. This meant that only Jews were thrown overboard (Davis 1867, 472). While this tale is framed as a pro-Christian, anti-Semitic polemic, the connection of the sequence with throwing people overboard is redolent of Sidonius’s account of the practices of Saxon pirates (Ahrens 1918, II, 118—68).