Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies - Nigel Pennick 2015

Magical Protection against Supernatural and Physical Attack

VIKING AGE MARITIME FIGUREHEADS

Early medieval ships in northern Europe carried removable images on the prow and stern posts. The dragons on Norse and Norman ships are the best known, serving to protect the ships against sea monsters and other evil denizens of the deep. Figureheads were removable so they could be taken from ships before docking or being dragged on shore, so that the land wights (landvættir) would not be frightened by them. Several old texts record the form and nature of these ships’ figureheads, and they can be seen on the Bayeux Tapestry as well. They appear in the account of the death of the Norwegian king, Olav Trygvason, in the maritime Battle of Svolder in 1000 CE by Adam of Bremen (ca. 1080) and Saxo Grammaticus (ca. 1200) in his Gesta Danorum (ca. 1200) and in Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla. These accounts tell of ships called the Crane, the Long Serpent, the Short Serpent, and the Iron Ram. The king’s flagship had formerly belonged to a Pagan martyr tortured to death by Olav for refusing to become a Christian. This ship’s prow had a gilded dragon’s head and a crook shaped like a tail on the stern.

Before the sea battle in which the king’s navy was defeated and Olav died, his enemies, the earl of Lade, Eirík Hákonarson, and the Swedish king Swein Forkbeard, were on their flagship and looking out for the flagship of Olav. King Swein is reported to have said that Olav was afraid of them so much that “he dare not sail with the dragon head on his ship.” As well as their figureheads, important ships were identified by colored sails. The Saga of Olav Tryggvason recounts Eirik Hákonarson’s attempts to identify the king’s ship, in which he notes a ship with striped sails as belonging to Erling Skjalgson as opposed to the dragon’s-wing sails of the king’s vessel (Saga of Olav Tryggvason, chap. 101—111). Sixty-six years later, Duke William’s ship Mora had a red sail.

The Mora was the flagship of Duke William of Normandy’s invasion fleet in 1066. It had a special figurehead, and on top of the mast flew Gonfanon, the consecrated banner given to William by the pope to empower him in his attempt to overthrow the English king, Harold Godwinson. The figurehead of the Mora was a brass figure of a boy, holding a bow and arrow in his right hand, and blowing a horn with his left. The Bayeux Tapestry shows this figure set astern, but Wace’s account sets it on the prow (Bruce 1856, 93). Removable figures could be set at either end of the ship, it seems. Other ships of the Norman invasion fleet had figureheads in the form of dragons, lions, and bulls. The Bayeux Tapestry shows the ships of the Norman invasion fleet drawn up on the shore of England at Pevensey, with all the figureheads removed. A ship shown still on the sea has its figurehead in place; another has it already removed. The sockets for the figureheads are clearly shown in the beached ships. The eleventh-century makers of the Bayeux Tapestry knew of the northern maritime practice, which was observed by Pagan and Christian alike.

MAGIC BATTLE FLAGS AND STANDARDS

Military flags and standards served to identify the army or unit in combat situations. They embodied the power, spirit, and ethos of the fighting force and were believed to bring it good fortune in battle. To capture the enemy’s standard was a sign of victory; to lose one’s standard, defeat. As long as the flag was flying, there was still fight left in the troops. A standard that became influential in the north was the dragon. This draco standard was adopted by the Romans from tribal warrior horsemen: the Alans, Sarmatians, and Dacians. The Persian and Parthian cavalry also flew dragons. It was described by Arrian of Nicomedia in Ars Tactica (137 CE) as a long sleeve made from pieces of dyed material sewn together. At the front was a hollow metal dragon’s head, supported on a staff. The mouth faced into the wind, and the fabric body trailed behind and filled with air, giving the appearance of a dragon in flight. Trajan’s Column in Rome depicts several Dacian examples of this standard. The Romans copied their enemies and introduced the draco. Cavalrymen carrying the banner were called draconarii. They are depicted in the Strategikon, a military manual of the time of the eastern Roman emperor Maurikios (reigned 582—602 CE). The legendary King Arthur was said to have a dragon banner of this kind; his father was Uther Pendragon, whose surname meant “head of the dragon.” Anglo-Saxon kings also had dragon banners, such as the white dragon of Wessex. The flag of Wales today is a Y Ddraig Goch, a red dragon on a green-and-white background. It was made official in 1959.

Between the ninth and eleventh centuries, the Raven Banner was the standard of Viking Age forces. The hrafnsmerki was a flag that depicted a black raven. From contemporary images, it appears that the banner was triangular or semicircular. Its edge was adorned with tassels or ribbons. The Orkneyinga Saga tells how, in the wind, the raven appeared to flap its wings and fly. There are extant descriptive accounts of the Raven Banner, both its appearance and its use in battle. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 878 records the capture from a Viking force of a guðfani (battle flag), called “Raven” by the army of Wessex in Devon, western England. The Orkneyinga Saga (chap. 11) tells how the Norse earl of Orkney, Sigurd the Stout, had a Raven Banner made by his mother, who was a völva. The magic banner would bring victory to the man it was carried before in battle, but the magic came at a price, for it would bring death to the actual standard-bearer.

At the Battle of Ashingdon in England in 1016, the army of King Cnut (Canute) had a white silk raven banner for their standard. Sturluson’s Heimskringla recounts that Harald Hardrada’s raven banner was called Landøyðan, “Land Waster” (destroyer of lands). It was clearly a magic banner, promising victory to those who carried it (Haralds Saga Sigurðarsonar 22). The banner’s luck failed in 1066, when Harald Hardrada’s invasion of England met with crushing defeat at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. The Bayeux Tapestry, commemorating the Battle of Hastings, the other famous battle of the fateful year 1066, has a depiction of a Raven Banner carried by one of Duke William’s cavalrymen. For his invasion of England, Duke William of Normandy had the gonfanon, a personal banner that was given to him by the pope. Heraldically it was argent, with a cross or in a bordure azure: a gold (yellow) cross on a silver (white) background, surrounded by a blue border. This is shown on the Bayeux Tapestry, and it was carried in the Battle of Hastings, in which William was victorious.

A battle in which no fewer than four consecrated standards protected the warriors was fought at Alverton (now Northallerton) and was recorded by Richard of Hexham. It was fought “between the first and the third hours” on Monday, September 22, 1138. Northern England had been invaded by King David I of Scotland’s army augmented by Pictish and Cumbrian contingents. They had devastated the northern part of England. The Archbishop of York called a crusade against the invaders, and a sacred standard was set up to call upon divine assistance and to serve as a rallying point. The carpenters brought a timber frame on wheels and erected a ship’s mast on it. This magic vehicle was the “Standard.” On the top of the mast they hung a silver pyx containing a consecrated host, and from cross arms four magic flags taken from the churches where they were kept: the banners of St. Peter the Apostle, St. Cuthbert of Durham, St. Wilfrid of Ripon, and St. John of Beverley. The latter had been carried in battle two hundred years earlier in 937 by King Æthelstan’s English army at Brunanburh. At Northallerton, William of Aumale commanded the English forces, and the outcome was a total rout of the invaders, and the survivors of the battle were hunted down and killed. After taking possession of the booty, which was found in great abundance, the English warriors returned home and “restored with joy and thanksgiving to the churches of the saints the banners which they had received.” Because of the wheeled mast, the battle has always been called the Battle of the Standard.

Some magic flags were reputed to have an eldritch origin that invested them with special powers. In Scotland the Mackays possessed an otherworldly flag presented to the clan by a fairy woman, and the Macleods preserved the Fairy Flag of Dunvegan, which was given to an ancient Macleod of Macleod on a visit to elfane (Carmichael 1911, 86). In eleventh-century England, Earl Siward of York was given a banner named Ravenlandeye by a spectral being whom he met on the seashore. Wearing a wide-brimmed hat, the mysterious being had the attribute of Odin. Siward, who fought against the Scottish king Macbeth, finally committed ritual suicide. On his deathbed he ordered his servants to dress him in his coat of mail and, holding his sword, take him up upon the walls of York. From there, he leapt to his death so that he might die like a man, not like a beast on a bed of straw. For many years the Raven Banner hung in St. Mary’s church in York. The retired standards of the British military are hung up in churches today. Once its use in battle is over, the magic flag should be returned to its place of keeping, on sacred ground.

Fig. 12.1. Apotropaic beasts around the door of Kilpeck church, Herefordshire, England, ca. 1150.

WIND VANES AND WEATHERCOCKS

Wind vanes are finely balanced artifacts that swivel on a fixed upright, driven by the prevailing currents of wind. The wind vane appears as the final rune of the first ætt in the Common Germanic Futhark. It is the rune wunjo (Anglo-Saxon wyn). It signifies the function of a wind vane that moves according to the winds, yet remains fixed in one place. Its reading is “joy,” obtained by having a stable base but being in harmony with the surrounding conditions. A traditional motto depicted with a weathercock in seventeenth-century emblem books is “officium meum stabile agitare” (“it is my function to turn while remaining stable”). In the Viking Age, gilded metal weathervanes were mounted on ships, and similar ones were set up on stave churches in Norway. The Raven Banner had a similar form.

The origin of weathercocks in the north is uncertain. They may have a southern origin. Early records are few. A ninth-century weathercock is known from Brescia, Italy, where Bishop Rampertus had one erected on the San Faustino Maggiore church in 820 CE (Novati 1904—1905, 497). They were in use in Anglo-Saxon England, as in 862 CE when Bishop Swithun set a weathercock on Winchester Cathedral. (In England, St. Swithun’s Day, July 15, is connected with the weather, as it carries folklore that warns of a rainy period of forty days afterward, if it should rain on that day.) According to Ekkehard IV’s chronicle Casus sancti Galli (chap. 82), in 925 CE the monastery of St. Gallen had its weathercock stolen by Magyar invaders who climbed the tower to remove it. In France in the year 965, a gilded weathercock on the abbey church of St. Pierre at Châlon-sur-Sâone was struck by lightning (Martin 1903—1904, 6). Westminster Abbey in London is depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, showing a man setting a weathercock on the top at its completion in 1065. Vanes and cockerels are not the only forms of traditional wind markers. A medieval saying from France tells us there are lions, eagles, and dragons on top of churches (Martin 1903—1904, 10). Swans are features of churches in parts of Germany, especially in Oldenburg and East Frisia (Goethe 1971, 7—19).

WOUND-PROOF MAGIC JACKETS AND BLOOD STANCHING

In the medieval history of the Norwegian kings, the Heimskringla, the Saint Óláfs Saga recounts an event in the Battle of Stiklastad (Stiklarstaðir) in Norway in 1031. The Norwegian farmers had risen in rebellion against King Óláf Haraldson’s arbitrary rule and his religious policy, under which he had tortured several Pagan martyrs to death for refusing to become Christian. One of the ringleaders of the uprising, Thorir Hund, a devout Pagan, wore a magic reindeer-skin coat obtained from the “troll-wise Finns,” which rendered him wound-proof; that is, invulnerable to edged weapons. In the battle the rebels led by Harek of Tjøtta (Hárekr ór Þjóttu) and Thorir fought their way through to the king and tried to kill him. The king struck Thorir Hund over the shoulders, but his sword appeared blunted and would not cut, and it seemed that smoke came out of Thorir’s reindeer-skin coat. Björn, the king’s marshal, then attempted to hit Thorir and, knowing he was wound-proof, turned his battle axe so that he could strike Thorir with the hammer end instead of the sharp edge. Thorir fell back injured but ran his spear through Björn. Then the king was killed (Óláfs Saga Helga, chap. 226—28). Scottish folklore tells of a magically protective jacket worn by magicians, the warlock fecket, that had to be woven from the skins of water snakes at a certain phase of the March moon (Warrack 1988 [1911], 656). A magical way of destroying a wound-proof man that features the number nine repeatedly is described in the legend of Lord Soulis, which is recounted in chapter 13.

The bloodstone is a traditional English remedy to stanch bleeding. According to East Anglian custom, one is hung around the neck on a red silk ribbon, tied with three knots at three-inch spacings. To activate a man’s bloodstone, nine drops of women’s blood are dripped onto it, and for a woman, nine drops of men’s blood (John Thorne, personal communication). English bloodstones are not actually gemstones, but specially made glass beads. In the author’s possession is an old bloodstone from King’s Lynn, Norfolk, made of blood-red glass. A bloodstone recorded in 1911 was of dark green glass containing white and orange twists (Porter 1969, 83). Similar glass artifacts have been found attached to scabbards of Germanic swords dating from the first millennium CE. The magical function of a scabbard is recorded by Sir Thomas Malory in Le Morte D’Arthur (Malory 1472, bk. I, chap. XXIII), where King Arthur receives the sword Excalibur and a scabbard for it. But although the sword is invincible, the scabbard is even more valuable, because so long as he has it, he can never die from wounds. In 1865 George Rayson noted an East Anglian remedy against nosebleed, to wear a skein of scarlet silk around the neck, with nine knots tied down the front. The knots should be tied by a man for a woman, and vice versa. He made no mention of the bloodstone (Rayson 1865c, 217).

HLUTR AND ALRAUN

Images are part of many religions, and the Celtic, Germanic, Nordic, and Slavonic peoples had sacred images in households, at important places in the countryside, such as crossroads, in wayside shrines, and in temples. In Pagan times, devotees of gods and goddesses also possessed and venerated small images. Portable humanoid images were being made in the Palaeolithic era, but whether or not they were goddesses cannot be known. Small images of Lares (household deities) were certainly in existence in northern Europe in Roman times, along with other figurines. The Lares were kept in a house shrine, the Lararium. In what is now France, the seventh-century Christian Capitularia Regum Francorum condemned images made from rags, “the image which they carry through the fields.” In Old Norse a portable image was called hlutr. The Vatnsdœla Saga mentions Ingimund’s hlutr of the god Freyr, which disappeared and finally turned up in Iceland. Images such as these were destroyed or hidden when the Christian religion became dominant. Roots of humanoid form may have taken over from actual images as less obviously Pagan in nature.

Fig. 12.2. Alraun, from the author’s collection.

There is a saying in Franconia, Germany, that if someone has unexpectedly good fortune he or she must “own an areile” (an Alraune or mannekin) (Lecouteux 2013, 134), a natural or artificially altered root of humanoid form, of which the mandrake is the best known.

The magic mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) is a member of the botanical family that includes the potato, tobacco, and woody nightshade species. It possesses a root that appears to resemble the human form, and in former times this was believed to shine at night like a lamp. The roots have two genders, man and woman, mandrake and womandrake. Because such a root resembles the human form, it is considered to be an earth sprite whose magical powers can be harnessed for the magician’s use. Womandrake roots were used as charms by women to promote childbearing, to bring prosperity, and to bring lovers the objects of their heart’s desire. Mandrake roots were also used in ceremonies to find out secrets and to locate lost property. The root of the mandrake resembles the roots of other plants, including deadly nightshade, white bryony, and bramble (blackberry). The white bryony (Bryonia dioica) has a much dug-for root that was used magically in the same way as the much rarer and far more expensive mandrake root. In Norfolk, England, white bryony is actually called mandrake.

Because they were much sought after for their magical properties, artificial mandrake roots were made. In Germany they were called Erdmannekin or Alraun, and in Great Britain mannikin. In medieval Germany, carved wooden alrauns were made that had grains of barley inserted in the places where hair or a beard should be. The alraun was buried in sand for three weeks, after which it was dug up and the grains had sprouted, making the appearance of hair. In Britain a more sophisticated method was used. In The Universal Herbal (1832), we are told:

The roots of Bryony grow to a vast size and have been formerly, by impostors, brought into a human shape, carried about the country, and shown for Mandrakes to the common people. The method which these knaves practised was to open the earth round a young thriving Bryony plant, being careful not to disturb the lower fibres of the root; to fix a mould, such as used by those who make plaster figures, close to the root, and then to fill the earth about the root, leaving it to grow to the shape of the mould, which is effected in one summer. (Green 1832, 201)

In 1832 this technique was seen as faking, but it appears to have been an old means of making a root effigy for magical purposes. Magic employs images of things and symbols of them to accomplish what the real thing can do (Agrippa 1993 [1531], II, XLIX). In his 1934 book The Mystic Mandrake, C. J. S. Thompson noted a report of a “manikin” made from a dried frog, with its head replaced by a root of Alpina officianarum (Thompson 1934, 122).

Real mandrake was used medicinally as an anaesthetic. Mandrakes were reputed to have the powers of rejuvenation and were used in love potions. In Britain, by the twentieth century the mandrake was obtained by the Wild Herb Men (the English rural fraternity of root diggers) only for horse doctoring (Grieve 1931, 510—12; Hennels 1972, 79—80). A medieval belief about the mandrake warned that it was dangerous to uproot the plant because to do so would bring certain death within the year. So magicians devised a technique to overcome this. They tied a dog to the plant and caused the dog to uproot it. But during the procedure, it was necessary to stop up one’s ears, because when uprooted, the plant gave a hideous shriek, and hearing this horrendous sound was dangerous. Magically, an alraun gave the owner protection against bad weather, warded off the nightmare, and assisted women during childbirth. Like the pothook, the alraun was seen as the protector of the family. However, possession of the magic root was also dangerous, for at some point its luck would run out.

Alrauns had to be treated well, housed in a box, and wrapped in white linen or silk. If an alraun was not respected, it would shriek its disapproval. This is part of the tradition that “no mascot will bring good fortune to one who is unworthy of it” (Villiers 1923, 1). It was believed that if an alraun was put into a glass bottle, it would transform into a spider or scorpion. It was supposed that the “imp” within the bottle could perform magical services for the owner, but if he or she should die possessing such a bottle, then the Devil would take his or her soul (Thompson 1934, 138). An alraun could not be disposed of easily, because it would inevitably return to the owner no matter what had been done to it. Places where people had made a futile attempt to dispose of an alraun gained an on-lay that brought misfortune to others who went there. In 1630 in Hamburg the possession and sale of alrauns was prohibited, and three women were executed for possession (Thompson 1934, 135—36).

HOLED STONES

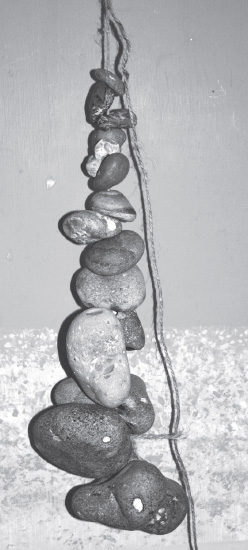

A stone with a natural hole through it is called a hagstone or holeystone. They have been recognized as magical since ancient times. It was a tradition to hang one on the back of the door in stables to keep the horses calm at night (Glyde 1872, 179; Evans 1971, 181—82), and over beds to ward off bad dreams. The customary thread in Great Britain is a string of flax. Especially magically powerful are holeystones taken from the beach and threaded together into a chain. A holeystone chain from Great Yarmouth on the east coast of England is illustrated here.

Fig. 12.3. Chain of holeystones from the seashore, Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England.

They are closely related to magic cords containing knots. Strings of magical talismans and amulets are worn as necklaces in many cultures; charm bracelets, called Wendekette and Friesenkette, in south German and Austrian tradition.

Holed flints were used by the Arts and Crafts architect Edward Schroeder Prior at strategic points on the exterior walls of Henry Martyn Hall in Cambridge. Holed standing stones and holes through stones in buildings are traditionally held in reverence as places of healing and foresight, and oaths were taken on them, a form of binding between two individuals. A holed stone called the Odin Stone stood at Croft Odin on Orkney until it was destroyed by a farmer in 1814. Oaths were sworn on the stone, and an offering of bread, cheese, or cloth left there. In 1791 a young man was brought before the Elders of Orkney as an oath breaker, “breaking the promise to Odin”; that is, an oath sworn on the stone.

MAGICAL BINDINGS

The Web of Wyrd is likened metaphorically to a woven fabric made on a loom; equally it can be visualized as a series of threads knitted together. Knots are the means by which garments are knitted, and people use knots to tie things up magically as well as physically, bringing them to a full stop. The way to ravel (tie up, or bind) things magically as well as physically is to use a knot to entangle and entrap the designated target. Binding spells are intended to be the magical equivalent of physical knots, nets, and ropes. In mythology, powerful, dangerous beings are captured and bound by the godly powers of proper orderliness. The Old Icelandic text Gylfaginning (34, 51) tells of the binding of both the Fenris-Wolf and Loki, and Christian eschatology in the Book of Revelation (20:1—3) describes the bondage of the Devil in chains for a thousand years. The conjuring parsons of eighteenth-century Cornwall would “lay” troublesome spirits and imprison them inside objects such as the pommel of a sword or a barrel of beer, or banish them to the Red Sea (Rees 1898, 266—67). In Manchester in 1825 a boggart was trapped and bound under the dry arch of an old bridge over the River Irwell for 999 years. Other magical binding legends and folktales from northern Europe follow the same theme. A traditional carving of the chained Devil exists in Stonegate, York, England.

In folk tradition the most feared power of the witch was the evil eye, “a magical and occult binding.” Magicians and witches claimed to have the power to use binding spells against merchants, so they could not buy or sell; against ships, so they could not sail; and against mills, so they would not grind corn. They were supposed to bind wells and reservoirs, so that water could not be drawn from them. Magically, they bound the ground, so that nothing could grow and be fruitful there, and neither could any building be put up. Writing about magicians in 1621, Robert Burton mentions knots among other methods of performing magical acts upon people: “The means by which they work, are usually charms, images . . . as characters stamped on sundry metals, and at such and such constellations, knots, amulets, words, philtres, and so forth, which generally make the parties affected melancholy” (Burton 1621, I, ii, I, sub. III). A person magically bound to do something, as in the expression “she is bound to die” is said to be spellbound. In his influential magical text of 1801, The Magus, which was largely plagiarized from H. C. Agrippa, Francis Barrett wrote:

Fig. 12.4. Bound devil, Stonegate, York, England.

Now how is it that these kind of bindings are made and brought to pass, we must know. They are thus done: by sorceries, collyries, unguents, potions, binding to and hanging up of talismans, by charms, incantations, strong imaginations, affections, passions, images, characters, enchantments, imprecations, lights, and by sounds, numbers, words, names, invocations, swearings, conjurations, consecrations, and the like. (Barrett 1801, 50)

A binding spell usually employed knots of some kind, but not always. An accusation of binding magic took place in 1662 in the Scottish highlands, when Isobel Gowdie of Auldern was tried for witchcraft. She made a long and detailed confession that led to her being sentenced to death: “Before Candlemas we went by east Kinloss, and there we yoked a plough of toads. The Devil held the plough, and John Young, our Officer, did drive the plough. Toads did draw the plough as oxen, couchgrass was the harness and trace chains, a gelded animal’s horn was the coulter, and a piece of a gelded animal’s horn was the sock.” The sock is the ploughshare. Using the horns of castrated animals to form the coulter and share of the plough would have been a magical act employing parts of infertile animals to bind the ground and render the earth infertile. This is analogous to the Old Norse magical procedures of driving out the land wights and thereby rendering the ground álfreka. Of course, it is impossible to plough a field using toads.

In Welsh Witchcraft (1975), L. Simmonds tells of a quincunx ritual of binding performed at Llanfechan, Wales. No date is given. A farmer lost several sheep, dead for no apparent reason, so he sent for a wizard from Welshpool to sort it out. The wizard asked the farmer to lead him to the exact center of the farm, and there he set up an ash pole. Then four more were set up, each twenty-five yards from the first, to the north, east, west, and south of the center. Then they walked round the center pole and went to each of the other four poles in order. At each direction they stood in silence as the wizard stared into space. With “will to do . . . bid to do,” the rite was over, and afterward no more sheep died (Simmonds 1975, 20). A nineteenth-century magical manuscript by Frederick Hockley is indicative of the areas magicians believed themselves capable of dealing with. It has a spell “to bind the ground, whereby neither mortal nor spiritual beings can approach within a limited distance.” This was achieved by making a magic circle of enormous dimensions. The diameter of these circles could be one hundred feet, more or less, according to the operator’s desire, or even larger with the intention of keeping all earthly or spiritual beings away from the place by between a quarter of a mile and a mile. Like the Llanfechan ritual, it involved the four quarters, north, east, south, and west, with a magical talisman containing the Seal of the Earth buried at each spot.

KNOT MAGIC

The thorn-bearing, winding, and tangling shrubs bramble (blackberry, Rubus fruticosus) and blackthorn (sloe, Prunus spinosa) both have turning-related names in Irish, dreas and draion. They are plants that form barriers in thickets and hedgerows and turn back or entangle animals and people who try to go through. Becoming entangled in thickets of thorns is a physical example of what was believed to happen to spirits when encountering magically charged knots and patterns. Nowadays, Cat’s Cradles made from string are seen as a children’s game, although identical string-knotting patterns are part of the repertoire of binding magic. In Scandinavia they are called trollknutar (“magic knots”), part of the northern circumpolar tradition of string-magic linked to shamanic practices. The northern English and Scots word warlock, meaning a cunning man or practitioner of spellcraft, is rarely used today except pejoratively. Because dictionaries have given it meanings such as “liar” and “deceiver,” the word has fallen from use. Magically, the power of warlockry is the ability to shut in or enclose; that is, a person who can perform binding spells. A warlock can make a warlock brief, binding knots, physical or psychic, intended to ward off evil spirits and to lock up or bind their effects.

There is a large body of lore from the north linking nine knots with healing and warding off illness as well as ill-wishing. The nine knots tied in the silk thread for English bloodstones have been mentioned above. A charm from the Orkney Islands, recorded in 1895, which used a thread of nine knots as a cure for an injured wrist or ankle, is typical. It was put on with this spell:

Nine knots upon this thread

Nine blessings on thy head

Blessings to take away thy pain

And ilka tinter of thy strain fire

(MACKENZIE 1895, 73)

Knots made in rope, cord, and netting for practical and magical purposes, as well for women’s hair-braiding, and interlaces made during performances such as sword dancing, are transitory, and there are few surviving examples from ancient times. But as the tradition continued into the present day, we have an understanding of some of their meaning in the unrecorded past. Certain kinds of knots played a part in magical tradition. The witch knot was a particular charm worn in a woman’s hair, while the triple knot called a St. Mary knot was a raveling used to hamstring animals and, by association, prevent actions magically. Sea witches also sold the winds in ropes tied with three knots. In his 1827 short story “The Two Drovers” in Chronicles of the Canongate, Sir Walter Scott recorded a Scottish knot custom associated with livestock: “It may not be indifferent to the reader to know that the Highland cattle are peculiarly liable to be taken, or infected, by spells and witchcraft, which judicious people guard against by knitting knots of peculiar complexity on the tuft of hair which terminates the animal’s tail” (Scott n.d. [1885], 171). This was known as St. Mungo’s knot, and a knot known as the meltie bow was tied on the cudgels used by herd boys to protect the cattle from harm (Warrack 1988 [1911], 354). In the late nineteenth century, Arthur Moore noted an account from the Isle of Man in which a young man found a woman performing a ritual at a crossroads near Regaby. She was sweeping a circle with a besom (twig broom). He took the besom from her and found that it had “17 sorts of knots” on it. He burned it at midday, and “soon after its destruction the woman died” (Moore 1891, 91).

Fig. 12.5. Dragons and binding knots on corner of timber-frame building, Limburg, Germany.

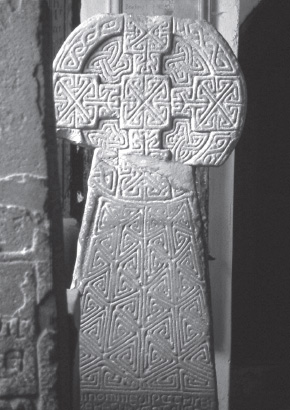

In Great Britain and Ireland, ancient examples exist of interlaced knotwork carved in stone and wood, tooled on leather, engraved on metal, and drawn in manuscripts. Today, this artistic knotwork is called Celtic Art, after the books of J. Romilly Allan, John G. Merne, and George Bain publicized the ancient art form under that name in the first half of the twentieth century. Many patterns are common to Ireland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Scotland, England, Scandinavia, and Germany. The ninth-century gritstone cross of Hywel ap Rhys, ruler of Glywysing, south Wales (d. 886), is shown in figure 12.6.

Fig. 12.6. Celtic Cross of Hywel ap Rhys, 886 CE, Llantwit Major, Wales.

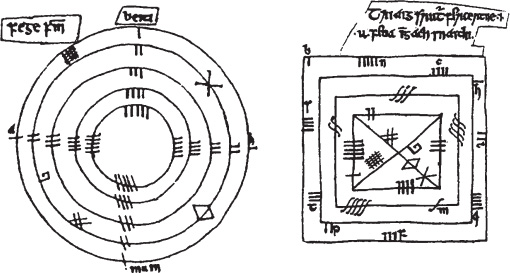

Fig. 12.7. Fionn’s shields, Irish Ogham. The Library of the European Tradition

Patterns called liuthrindi are known from ancient Ireland, used in a military context to disorient enemies. The Irish Ogham sigil Feisifín, Fionn’s Shield, can be in a circular or square form. It served as a protective talisman, and its form also resembles certain Icelandic sigils.

The simplest interlaced knot, the fourfold loop, is a very ancient magical sigil. It exists in Roman mosaics of the Imperial period, and early Lombardic and Romanesque churches in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy have the sign carved in stone on column capitals, fonts, and stone screens, where they appear among other interlace patterns. In the north, one survives on a memorial stone on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea (Havor II, Hablingbo parish). Dated between 400 and 600 CE (Nylén and Lamm 1981, 39), it appears also on bracteates from Denmark of similar date (Wirth 1934, VIII, pl. 424, fig. 1b; pl. 427, 7b). This and other protective glyphs were carved by the shipwrights on the pivoted wooden oar covers of the Viking Age ship excavated at Gokstad. On the Isle of Man, it exists on the Andreas Cross. It can be found widespread in medieval graffiti in Great Britain (see Pritchard 1967, 133). This simple knot is called Sankt Hans Vapen in Sweden, and in Finland and Estonia it is Hannunvaakuna (Strygell 1974, 46). One is shown on a 1673 engraving of a Sámi shaman’s drum in Johannes Schefferus’s Lapponia. In 1901 the Arts and Crafts architect W. R. Lethaby used the pattern in the tracery of the north transept window in his symbolic church at Brockhampton, Herefordshire, England (Mason 2001, 14).

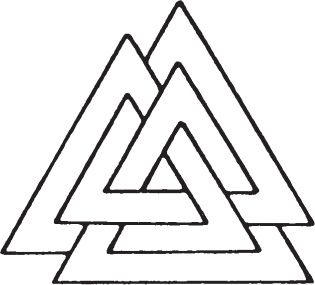

With an additional central cross loop, this fourfold loop was used on traditional English clog almanacs to mark All Saints’ Day, November 1 (see Schnippel 1926, pl. II and III). In the Country Calendar, it represents the midpoint between autumn and winter, and from this it has become the sigil for Samhain used by present-day Pagans (see Pennick 1990, 35, figs. 8, 13, 26, 35). A sigil composed of three interlaced equilateral triangles is seen frequently today as a symbol of northern religion. It is the Valknut (Valknute, Valknut, or Valknútr), the “knot of the fallen” (i.e., the slain). Among the earliest known examples of the sigil are found on some memorial stones on Gotland and on rings and other Viking Age metalwork. It is associated with the god Odin (Thorsson 1984, 107; 1993, 11; Aswynn 1988, 15—54).

A different form of triangular knot, with a superimposed cross, is known as Sankt Bengt’s Wapen (Strygell 1974, 46). In the Alps some people called up the demonic entity called Schratl by magic at crossroads, but the apotropaic device called Schratterlgatterl or Schradlgaderl is a means of warding off evil spirits, blocking their paths with a physical binding knot. This device was made from seven slivers of wood, interleaved to hold together without binding with cords. It was hung on doors or gates considered at risk from spirit attack (von Alpenburg 1857, 369; Bächtold-Stäubli 1927—1942, I, 297). Old Scratch’s Gate is a similar magical binding pattern used in East Anglian magic. Old Scratch is a byname for the Devil, and the sigil was chalked on doors and shutters to block the entry of evil. Every form of magic has a magical antidote, and a story told by the Anglo-Saxon chronicler Bede (Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, IV, 22) tells of a runic antidote to binding. In the year 679, Bede wrote, the shackles fell off Imma, a Northumbrian prisoner, every time his brother said Christian prayers for his soul, believing he was dead. Imma was asked “whether he knew loosening runes and was carrying staves with him written down.” Loosening runes had a Latin name, litteras solutorias.

Fig. 12.8. Valknut.