Rats: Observations on the History & Habitat of the City's Most Unwanted Inhabitants - Robert Sullivan (2005)

Chapter 5. BRUTE NEIGHBORS

IN THE CITY, rats and men live in conflict, one side scurrying off from the other or perpetually destroying the other's habitat or constantly attempting to destroy the other—an unending and brutish war. Rat stories are war stories, and they are told in conversation and on the news, in dispatches from the front that is all around us, though mostly underneath. If you ask people about rats at watercoolers or cocktail parties or over cake at the birthday parties of small children, then you may hear the story of the bartender who had a rat fall from his thatched-roof-decorated ceiling onto his bar where he quickly clubbed it or of the busboy who used a BB gun to shoot rats out in back of a jazz club on Fifty-second Street or of the graffiti artist who remembered a pack of rats falling down on his head from the top of a dormant subway car or of the woman who was enjoying a cocktail one cool summer afternoon in a cool outdoor cafe in Greenwich Village when a rat ran across her shoe on its way into a hole in the sidewalk or of the men, women, and children who have watched them intently in the subways, as they run across platforms, sometimes get on board subway cars, then detrain at subsequent stops. A particularly good rat story—and I have heard many—was told to me by a research librarian named Stan, who was, at the time of his rat story, living on the Upper West Side. It goes like this: "I was in my bedroom—I had two roommates at the time, but they were both out for the evening—and I heard a noise in the bathroom. Sort of a rustle-around kind of noise, so I got up and peered into the bathroom, looked all around, and that's when I saw the giant rat running around inside the bathtub. I screamed like a girl and closed the door. Then I poured a glass of scotch to think things over, and I decided my best option would be to poison the rat without trying to confront it. So I looked around for some kind of poison in the apartment and all I could find was furniture polish—it was Lemon Pledge—and also I thought I remembered something about rats liking peanut butter, so I mixed some Lemon Pledge with peanut butter and put it on a tiny piece of cardboard and slid it under the door and then waited. After about fifteen minutes I decided to peer in, and the peanut butter was untouched. So then I looked in the bathroom and didn't see it. And then I looked around and it was up on the sink staring at me. And then I screamed like a girl again and closed the door. I had another scotch and ultimately decided I needed to go in there and confront it, so I opened the door, didn't see it anywhere, looking all around, but there was a towel on the shower-curtain rod blocking a window ledge, and I figured it had to be on the ledge, so I grabbed the towel to pull it down, and I can't figure out to this day if I saw the rat on the ledge or it just dropped down into the bathtub, but now it was running around in the bathtub as scared as me and it couldn't get out—its claws were scraping—and so I decided I could drown it. So I turned on the water, waiting for it to drown, and that's when I had the tragic realization that rats can swim. But then I thought I've got it trapped, so now I just have to kill it, and I went back to the kitchen looking for something more poisonous than Lemon Pledge and I found the Comet kitchen cleanser. So I went back in and the rat was swimming around in one end of the bathtub, and I poured a bunch into the other end of the tub, and it formed this large, scary green pool. The rat swam toward it, and the second it hit the pool, it turned belly-up. Then I realized I had to get it out of the tub, and I didn't want to touch it, so I used a plastic bag and cut holes in it to drain the water, and I ran it out to the incinerator chute."

CITIES ARE LIKE PEOPLE IN that they all have their own rat stories. In Los Angeles, people talk about black rats in palm trees and rats in large and beautiful swimming pools—and I personally know a guy who traps rats at his arid, in-the-hills home and then releases them on the concrete banks of the Los Angeles River, which to someone who doesn't live in Los Angeles looks a lot like a large cement drain. In Boston, many rat stories surrounded the construction of the huge, under-the-harbor highway, known locally as the Big Dig, when it was feared that rats would take over the streets but didn't, thanks to a preventive rat campaign—though to be sure there were a lot of rats. In the seventies, London was gripped with a rat story that had t6 do with the rat-poison murder of an exterminator. A historic measure of Paris's urbanity has been the description by Parisians of large rats on its subway system, or metro. I recently visited Paris with an eye toward seeing large rats. When I did not, after spending several hours being watched on metro platforms by wary Parisians, I began to understand that being able to readily spot rats in a specific city is an acquired skill, akin to learning a local dialect.

As is the case in all cities, rat stories considered newsworthy in New York usually have to do with lots of rats, those engagements in the saga of man versus rat that are characterized by huge or seemingly huge rat infestations. Few neighborhoods have been without these infestations. A typical infestation occurred in the Flatlands section of Brooklyn over a few summers during the 1960s. "The children can't go to the store and they can't go to the library because of the danger of rats," said a woman who showed up to protest the infestation at City Hall—protests are a feature of city rat infestations. And rat infestations are not merely a modern phenomenon; they appear throughout the history of the city, dating from the Revolutionary War. For example, rats were reported in unusually large numbers all over Brooklyn in 1893; as usual, there was an explanation, a shifting in the city's functions. In 1893, horse-drawn trolleys were replaced with electric trolleys. The absence of horses in the trolley company's stables meant the absence of horse food. The hungry rats marched out into adjacent homes.

Sometimes, several infestations occur in the city at once, or what appear to be several infestations—there are, of course, rats throughout New York at any given time—and this results in the perception that rats are gaining ground against humans—i.e., winning the war. When this happens, certain predictable patterns of behavior occur on the human side. First, the city moves to a higher state of rat alert, and as a result New Yorkers begin to see rats where they never noticed them before. Then, whoever is mayor at the time makes numerous statements that seek to reassure the public that the "ugly conditions," to use the phrase of Mayor O'Dwyer in 1949, will be taken care of. "Something should be done," O'Dwyer said in a statement that was followed by the appointment of a citywide rat specialist. In 1997, during a rat alert, the city formed the Interagency Rodent Extermination Task Force. "New York City is about to launch the most comprehensive rat routing in history," one report said. This rat offensive was typical in that the city trapped and poisoned rats until the rat population was reduced but of course not eradicated.

A more recent example of a rat war occurred when rats infiltrated the garbage of the Baruch Housing Projects on the Lower East Side. The rats fed on garbage thrown into a fenced-off area reserved for garbage. There, the rats multiplied quickly and began to make forays into people's apartments. Subsequently, several television news crews filmed the rats roaming the nearby streets. Television footage of rats can be startling, but after you have seen it a few times it all appears the same: garbage backdrop, rat running, rat apparently startled by television camera's lights, rat turning, rat retreating. In the Baruch case, as often happens in cities everywhere, the rat problem fed upon itself, like rats eating rats. There was a rat protest at City Hall. People chanted, "One rat, two rats, three rats, four. Everywhere I look there's more and more." The mayor at the time, Rudolph Giuliani, became defensive about the rats; he complained that his efforts to kill rats had been ignored. "We make unprecedented efforts to kill rats," he said. "We kill more of them than probably anyplace else. We probably lead the country in rat killing." Around the same time, rats were spotted on the porch of Gracie Mansion, the official residence of the mayor. The mayor subsequently increased his attention to rat issues. He appointed a "rat czar," a position that, from a tactical point of view, was not significantly different from the position held by former mayor O'Dwyer's rat specialist. A week later, a city councilmen organized what was billed as a "Rat Summit." At the summit, a rat expert gave a talk with slides ("I'm not going to show any live-looking pictures today because people are often afraid of that," the expert said), and exterminators handed out cards, and a garbage disposal salesman showed off a new garbage disposal, and a man representing apartment dwellers plagued by rats testified about the time he dressed up in protective football gear and went after the rats in his apartment with a baseball bat. The councilman who organized the summit, Bill Perkins, said what will likely be said in one neighborhood or another as long as rat and humans coexist: "This is war!"

What I think of as one of the biggest New York City rat battles ever is the Rikers Island rat battle, which began around 1915 and lasted well into the 1930s. Rikers Island is a little island in the East River at the opening of Bowery Bay, in Queens, just one of many islands in the East River and all around New York. (Even New Yorkers forget the city is an archipelago.) Once, Rikers Island was small and bucolic and green, an eighty-seven-acre patch of land owned since 1664 by a family of early Dutch settlers named Rycken. The city annexed the island in 1884 and used it as a dump for old metal and cinders. It was one of the first designated dumps in New York, a response to increasing problems in the city stemming from the garbage being dumped offshore; shipping was frequently obstructed by floating trash, and oystermen complained of raking dead oysters out of garbage. Rikers Island worked as an antidote to the garbage problem until people began to complain about Rikers Island. Very soon, Rikers Island had grown into a five-hundred-acre island, a mass of garbage on and surrounding the original island, which, in addition to being a dump, was now also home to a prison farm. "Such a mass of putrescent matter was perhaps never before accumulated in one spot in so short a time," Harper's Weekly wrote in 1894. One of the complaints about Pikers Island was rats.

Rats from all over the city came to Rikers Island, arriving on the fleet of garbage scows. Within the island was a seventy-five-acre lake of stagnant water, and the rats lived along the shore, feeding on the garbage, drinking in the refuse-infused lake; with its garbage and its putrid isolation, Pikers Island was a rat Utopia. An official with the department of corrections at the time estimated that there were a million rats. The rats ate the prison's vegetable garden. The rats ate the pigs on the prison farm. The rats ate a dog that was supposed to kill the rats. The corrections department baited and trapped, but as is often the case in particularly large infestations encouraged by particularly large amounts of potential rat food, the rats bred faster than they could be killed. There was a suggestion that the city bring thousands of snakes to the island so that the snakes could kill the rats, then a suggestion that the rats be killed with biological weapons—the rats would be inoculated with rat-destroying bacteria, via a poison sprayed onto the garbage shores. Neither of those suggestions were acted upon. Then, in 1930, rats from Rikers Island began to swim the river to Roslyn, Long Island, a high-toned summer community. That fall, according to newspapers, the sanitation department used World War I-era poison gas to kill some of the rats. The next year, a Manhattan dentist named Harry Unger organized a hunting party of a dozen rifle-armed men. Unger and his posse were about to invade the island until the city called them off, fearing the hunters might shoot the prison guards or possibly each other. At last, in the spring of 1933, two exterminators—the Billig brothers, Irving and Hugo Billig—had some success when, after supervising the placement of twenty-five thousand baits around the island, they carried off two thousand rat carcasses on the first day. They estimated three million rats were living on Pikers Island. They estimated that they would be able to kill twenty-five thousand rats, and they saw those rats killed as an investment toward rats that would not need to be killed in the future. (It is not known how many rats they actually killed.) "Remember," Irving said, "each female rat can have four litters a year. Every litter contains from five to twenty-one rats. These young rats will have families of their own in four months, and their children will be having other children in four more months. Now, just figure how many rats we have killed by killing twenty-five thousand." The Billigs were successful, in that they reduced the population significantly, though modern studies indicate that Irving Billig probably underestimated the rat's reproductive capacity.

There was a time when the city was so full of rats that the presence of rats wasn't news; the news was the rats' absence. Rather than resembling a guerrilla force, rats were like an occupying army. This was primarily because of the amount of garbage in the city that rats were able to live on in the middle of the nineteenth century. "Besides the natural accumulation of filth on the streets from the dung of horses and other animals, there are vast collections of refuse matter—offal from houses, peeling of potatoes, the refuse of cabbages, and all those things which the ragpickers and hogs do not carry off—they are allowed to accumulate in very large quantities," said Professor Alfred C. Post, in testimony to the New York State Senate in 1859. Rat news at the time tended to be about new types of extermination, or exterminators who did notable work with snakes or ferrets, or unusual rat-related events. Sometimes macabre rat anecdotes were reported; in the 1880s, rats ate bodies kept at the coroner's office on Chambers Street. But frequently, rat anecdotes were almost cheery. In July of 1897, Peter Drapp, a florist on the corner of Thirty-eighth Street and Fifth Avenue, attempted to kill a rat with a pair of scissors, and missed, occasioning a long prose piece entitled HARPOONED A POLICEMAN. "Like Apollo of old, whose bad aim with a discus gave Mr. Drapp the hyacinths he sells, Mr. Drapp threw wild," the Times wrote.

The majority of New York's rat news has mostly had to do with death—primarily, the death of humans by rat poison. A lot of rat poison deaths are suicides. In 1886, when Joseph F. Conway, an unemployed trolley car driver, who had emigrated from Ireland to Kips Bay, killed himself with rat poison after other methods failed, a newspaper headline said: FIRST ROPE, THEN RAT POISON. But there were many accidental rat poisonings. For example, Howard Mettler arrived home from work in 1899 and ate a pie that his wife had made. After finishing, he told his wife that the pie tasted strange. She then told him that she had made it for the rats in their cellar. Mettler immediately called a doctor, who gave him emetics, which he took until two in the morning, when he died.

In 1913, in a three-story town house on West 103rd Street and Manhattan Avenue, a woman was accidentally killed by an exterminator named Christopher Walden. Walden went from room to room in the empty house, and in each room he shut the windows and placed a little pail into which he poured cyanide of potassium. Then, Walden poured sulfuric acid into each pail, running out of each room after he did. The rooms filled with deadly gas. He locked the front door. At the end of the day, the exterminator returned to the house and, with his face covered, opened the windows, until he came to the second floor, where he found a tenant, who had let herself back into the building during the day and climbed to her floor and then died on her bed. The woman, Kate Calder, was sixty years old and she had moved to the apartment six weeks before with her husband, William Calder, a tailor. They had moved to New York only after their home in Massachusetts had been destroyed by fire. Walden, the exterminator, was not charged, but I can only imagine how horrible he must have felt.

THE GENERAL SANITARY CONDITION OF America's cities changed as the twentieth century began. In New York, garbage began to be collected, for instance, and the city hired a man to haul dead horses from the streets. Consequently, the tenor of the war changed, as rats were slightly more scarce in some areas and, thus, a little more newsworthy in their appearance. After World War II, newspapers still ran stories about rat infestations in various neighborhoods, but the rat stories that were given the greatest prominence described rat infestations in high-income neighborhoods. They are reported with shock.

Just after New Year's Day, in 1969, for example, rats were spotted on a swanky stretch of Park Avenue—in particular, in one of the traffic medians that in the spring are decorated with tulips, the bulbs of which rats like to eat. "The rats, at times numbering in the hundreds, according to witnesses, have drawn early evening crowds of curious spectators to the island that divides the north and south roadways between 58th and 59th Streets," the Times wrote. The report continued, "Some of the bolder rats, they said, even crossed Park Avenue recently to forage in the sidewalk trash baskets near Delmon-ico's Hotel, 502 Park Avenue, at Fifty-eighth Street." At the time there were also huge rat infestations in Harlem, the Lower East Side, and Brooklyn; in 1969, the city was working to exterminate rats in an area of 1,600 blocks in predominantly low-income neighborhoods. But the Park Avenue rats were followed with great scrutiny. Most of the rats there were exterminated in two weeks. The Times called the Park Avenue rats "refugees from Harlem, where no one in authority seemed terribly concerned about their deprivations." Of course, students of rat behavior will tell you that the rats were not refugees from Harlem. Harlem is a mile away. The rats were Park Avenue rats. Still, the notion persisted that rats somehow didn't belong on Park Avenue, that Park Avenue was not their habitat. A woman living near the infestation said, "The idea of rats crawling around on children in the ghetto really hits home when you see them on Park Avenue."

The discrepancy between people who had rats and people who did not was underscored in 1959. It was a time when Americans and N ew Yorkers were thinking pretty highly of themselves, when people on Park Avenue felt safe from rats. It was during the Cold War, and Soviet officials were in Manhattan visiting a technology show that highlighted Soviet inventions. A headline in the Daily News boasted U.S. EXPERTS WANDER AT RED SHOW & WONDER AT NOTHING. The same week, however, a three month old baby died in Coney Island. His mother had heard him crying in the night and thought he wanted a bottle but soon discovered he was being bitten by rats. The baby had been sleeping in a carriage in the kitchen, and he was bitten repeatedly. Between January of 1959 and June 1960, 1,025 rat bites were reported in New York, twice as many as reported in the next ten largest U.S. cities combined. Sixty thousand buildings were identified as rat harborages by the city's health department—buildings constructed before 1902 that had been designed to house a few families and were now housing dozens. In 1964, nine hundred thousand people were reported living in forty-three thousand old law tenements. And then, rat-wise, things got worse. After the demolition of many of those buildings, in the pits of garbage-injected rubble, rats multiplied. The situation was described in one account as a "rat paradise."

The following year the Daily News began a campaign that was intended to rid low-income neighborhoods of rats, as well as sell the Daily News. The campaign featured what is perhaps the greatest number of rat stories ever published in one newspaper at one time. The campaign was entitled "The Daily News' do-it-yourself campaign to rid New York City of 8 million rats." The Daily News paid for teenagers to be trained in rat extermination; News employees handed out thousands of pounds of poisonous bait from what the News called "anti-rat stations," which were often News trucks filled with poison. For several weeks during the summer, the paper ran rat story after rat story, written in that Some headlines:

THE NEWS OPENS ALL OUT WAR ON RATS

1,000 TEENERS WILL SPEARHEAD ASSAULT ON RATS

RAT-BATTLERS TAUGHT TO KILL HIDDEN ARMIES OF RODENTS

THIS IS IT! WE PASS AMMO TO TROOPS OF THE ANTI-RAT WAR

WAR IS ON! RAT-BATTLERS OPEN ATTACK IN E. HARLEM

CITY'S RATS ARE LIVING IT UP ON MEALS THAT WILL BE FATAL

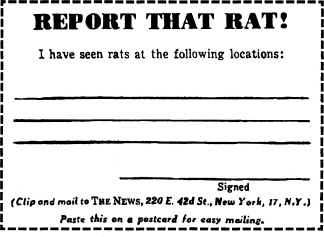

The News published a clip-out rat reporting coupon that looked like this:

Often dispatches from the rat war are just rat observations in the field, undertaken by the local citizenry—little accounts that turn the citizens of New York into nature writers, even poets.

From a letter to the editor of a newspaper on October 6, 1905, signed "Precautions": "During a seven minutes' walk from 116th to 118th Street in Morning side Park yesterday, I saw crossing or attempting to cross the alley five rats, one of them of uncommon size."

From a doorman on the Upper East Side, in 2002: "They are huge, big five-pounders or more. They come out right in front of you and you've got your breakfast in your hand, and you drop the bag and you start running."

From a news account in 1889, based on the observations of the night watchman at the ruins of the old Washington Street Market, an open-air market that had just been demolished that year—the area was said to be alive with rats: "He heard a scuffling noise under the boards at the end of the pier, and, holding his lantern over the string piece, he bent his body cautiously forward and saw an eel trying to lower itself into the water, but badly handicapped in its efforts by a rat that was hanging to its tail. The eel, after the manner of its kind, had crawled from the water in the night to search for food, and had found the rat. The rat, too, was looking for a meal, and was glad to meet with the eel; but when each discovered that its intended supper wanted to eat it, a fierce encounter ensued. Judging from the appearance of the combatants when the watchman saw them, the rat was getting the best of the contest, and, though somewhat lacerated, was fighting with the unbounded confidence of assured success, while the eel was evidently running away. The light of the lantern startled the rat, and, opening his jaws, he allowed the eel to escape into the water, while he went sulkily back into the darkness. The watchman thinks the eel was a yard long, and the rat, he says, was as big as a well-grown cat."

And finally, a firsthand report from a man running down the steps of a tenement in Brownsville, a burned-out and at that time almost uninhabitable section of Brooklyn, which Mayor John Lindsay toured in 1967, the year there were riots in many American cities, though not in New York, in part because Mayor Lindsey was in the streets; the man had a just-killed rat in his hand: "This is what's happening, baby!"

ONE OF THE MOST AMAZING rat skirmishes ever happened downtown in 1979, when a woman was attacked by a large pack of rats.

It happened on a summer night, just after nine o'clock. The woman was described by the witnesses as being in her thirties. She was on Ann Street, right near the entrance to Theatre Alley. Judging from the various accounts, she seems to have been approached by the rats as she was walking toward her car. She also seems to have noticed the rats coming near her, their paws skittering on the street. Witnesses said the rats swarmed around the woman. One climbed her leg and appeared to bite her. The woman screamed. A man nearby ran to help the woman, taking off his jacket and waving it in an attempt to scare the rats away. The man told police that the rats appeared undeterred by anything he did, and in a second they began to climb up his coat. Seeing this, the man ran to a phone and called the police. By now, the woman was "in a state of hysteria," according to another witness. She staggered to her car, which was parked a few yards away. The rats followed her. She got in, closed the door. Now the rats were climbing on her car. She was screaming when she drove away. The woman was gone by the time the police arrived, but the rats were still there, scurrying through the street and into Theatre Alley and into their nests in a lot on Ann Street, just around the corner.

The lot where the rats lived had been a bar that had blown up nine years before. Ryan's Cafe was an old stand-up bar in a building that was thought to date back a hundred years. It exploded at two in the afternoon on December 11, 1970, shortly after some customers had complained of smelling smoke and two workers went to the basement to turn off a water heater. Eleven people were killed and sixty were injured. After it exploded, people were clawing through rubble, bloodied and crying. In City Hall, across the street, the mayor thought he'd heard thunder. Police helped a man crawling from the rubble; his clothes were smoldering. A nurse ran over from the construction site, one block west, where the World Trade Center was being built. "Dirty white smoke curled high across Broadway, wreathing the spire of St. Paul's to the southwest, drifting across the ornate front of the Woolworth building to the northwest, finally dissipating around the skeleton of the World Trade Center far to the west," a newspaper reported, adding, "The explosion drew hordes of spectators."

A short time later, the old building was demolished. Rats began to nest in the resulting hole in the ground, feeding off the garbage in Theatre Alley. They thrived in the forgotten-ness. Then, in 1979, there was a tugboat strike. Whereas the city customarily transported sixteen barge-loads of garbage every day to the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, during the tugboat strike the garbage was all backing up in New York's streets. Eventually, President Jimmy Carter declared a health emergency in New York City and ordered the Coast Guard to tug trash barges, but in the meantime trash was tossed into the old lot that had once been Ryan's Cafe. The old lot that was once ideal rat habitat now was the ideal ideal rat habitat. And the strike had gone on for weeks; the streets had not been cleaned for three months. An artist, Christy Rupp, who lived across the street from Theatre Alley, had been hanging up drawings that she had made of large rats, to draw attention to the rat situation. Rupp said she had seen fifty rats in three hours on the night the woman was attacked. "Rats are everywhere," Rupp said shortly after the woman was attacked by rats. "They are very successful urban animals. They are king in New York." (After the Ann Street incident, Rupp went on to create plastic sculptures of rats—rats standing, crouching, and rolling over.) Meanwhile, the identity of the woman who was attacked was never discovered. The police called area hospitals but no one reported being attacked by a pack of rats.

Randy Dupree was the head of the city's pest control bureau in 1979, and on the night of the rat attack near Theatre Alley, he was in upstate New York, at a rat control convention. After the rat attack, the mayor, Ed Koch, telephoned him and ordered him to return to the city immediately. The next day Dupree was watching the rats run back and forth to Theatre Alley for food. Initially, Dupree estimated one hundred rats were living in the lot. The bureau began trapping and poisoning. They used peanut butter laced with poison. Workers in the pest control bureau crawled down into the hole and beat the rats with shovels and clubs. Dead rats were flying around the hole that was Ryan's Cafe. Reporters who went down into the hole ran out frightened. The workers dug through foot after foot of pipes and lumber and rotting garbage—two tons of garbage in the end. The first day they killed a hundred rats. Dupree was forced to upgrade his initial estimate of the rat population after they killed a hundred more.

I ran into Randy Dupree at the Rat Summit in New York City a few years ago and arranged to meet him for lunch one day in a restaurant in Manhattan. Dupree had recently retired as head of pest control for the city after twenty years; when we met, he was consulting for pest control companies in the city. "I surveyed every block in New York City for rats," he told me. He still finds himself looking for rats wherever he is, checking the streets, looking around restaurants. "Instinctively, I do," he said. "Runways are always there." He shook his head. "You know, I tried to divorce myself from rats. I said, 'I hate rats. I don't like 'em.' But then, there came a time I said to myself, 'Randy, hey! That's what you do! That's who you are!' Now, any of my friends, they see a rat, they say, 'Where's Randy at?'"

Dupree had no problem recalling the rat attack off Theatre Alley: "I remember that, I sure I do." His explanation of the attack made it seem less warlike and more accidental, a crossing of human and rat paths. "What I think happened is—well, this lady, she got off work at eight or nine o'clock, and it was getting dark and that's when the rats would have started migrating from the alleys. And then, what happens first is, the lady sees the rats. And then the rats see her, and then she starts running and then the rats start running, because look—they're just as scared as she is. And they're there, all of them just running along. And so it looks like they're attacking her. But then because she thinks they're attacking her, the rats get scared and then they actually do."

Dupree has the confident smile of a man who has heard his share of rat stories. "Number one," he said. "Most people exaggerate. You know, the rats-big-as-cats stories. You start to discount them." On the other hand, he has his own rat stories that stretch the limits of the imagination, such as the story about the rats that were discovered in the 1980s in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx, in a place called St. Mary's Park. All of the rats in St. Mary's Park were tested to be resistant to poison—they were so-called Super Rats. "When word got out, you couldn't find a person who would go into St. Mary's Park in the Bronx," Dupree recalled.

As he was telling me about the park, Dupree suddenly noticed a small fly on the table. He stopped talking, watched the fly for a second, then caught it. He looked at it closely in his fingers and placed it in an envelope. He put the envelope in his pocket. "I'll check that when I get back to the office," he said.

He resumed talking. "Anyway, I remember those rats downtown. Yes, I do."