A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Leek (Allium porrum)

Family: Amaryllidaceae: daffodil family; formerly Liliaceae: lily family

Other Names and Varieties: overwintering leeks, summer leeks

Healing Properties: lowers cholesterol and blood fat levels; hinders fungi and putrefactive agents in the intestines; helps to prevent constipation, gout, hemorrhoids, lumbago, urinary tract ailments, and varicose veins

Symbolic Meaning: health, protection against wounds; heroic courage, manly virtue, victory; national emblem of Wales

Planetary Affiliation: Mars, moon

While the Swiss, especially the French Swiss, have long treasured leeks as a gourmet garden vegetable, in America they are a relatively new among the vegetable selection; in Germany they are basically only used to give soups and sauces more flavor. But this robust member of the Liliaceae family, a relative of onion and garlic, deserves a closer look. Leeks are easy to care for, take up little room, and can be left in the garden over the winter. The leek’s sulfuric essential oils, which also provide its healing properties, allow it to resist frost even in the coldest weather, making it, and the lamb’s lettuce discussed above, an important winter and spring vegetable. It has a whole palette of vitamins—A, B, and C, and fertility vitamin E—as well as rare minerals such as zinc (good for connective tissue and the body’s natural hormones), manganese (important for metabolism and sex drive), and selenium (which supports the immune system). It is thought that one can overcome leaden spring fatigue with a dish of leeks with spring herbs and eggs. One disadvantage: leeks cause flatulence, but preparing them with caraway seeds counters the effect; indeed, a popular cheese-scalloped Swiss dish pairs sautéed leeks and carrots with caraway seeds.

The leek has been cultivated in the eastern Mediterranean region for at least four thousand years. In ancient Egypt it was not only a common vegetable but, like the onion, it was regarded as a symbol of the universe—each layer of leaves standing for a stage of the demonic or divine other worlds. In the Fourth Book of Moses (Numbers) we read that the children of Israel, before reaching the Promised Land, implored Moses about their bland manna diet: “We remember the fish, which we did eat in Egypt freely; the cucumbers, and the melons, and the leeks, and the onions, and the garlic …” (Numbers 11:5).

Illustration 46. Drawing of a leek

The Greeks and Romans dedicated the leek to Apollo. Indeed, at the Delphic festival of the sun god Apollo, whoever brought the biggest leek as a gift to Leto, the mother of the gods, was given the honor of eating a portion at the god’s banquet. But nowhere were more leeks (porrum) eaten than in old Rome. It was Nero’s favorite food. He considered himself to be a great musician, and is said to have eaten a bit of raw leek dipped in olive oil every day in order to preserve his sonorous singing voice. This habit earned him the nickname “Porrophagus,” (leek eater). While it is more common to eat it cooked or baked, small amounts from the tender inside can also be eaten raw.

It is questionable whether the Germanic tribes knew of the leek before the Roman army and settlers introduced the “Welsh leeks”—“welsh” referring to foreign—to the countries north of the Alps. The plant joined company with the many other various kinds of “leeks”—all of which were considered to be sacred, curative, and magical plants. Almost every edible fresh, green shoot or leaf that popped out of the ground after the long winter that was capable of reviving the spirits used to be called “leek” (from the Old Norse laukr, Dutch look, and Old English leac). Such plants gave the men more virile strength, gave the women cheerful smiles, and restored the children’s rosy cheeks. These different kinds of “leeks,” considered gifts from vegetation goddess, Freya, embodied the virtue and nobility of green vegetation.1 The various fresh green shoots and leaves were seen as the pointed spear tips, or swords, that drive back obdurate, hostile ice and frost giants—as well as demons of disease and lingering illness. The word “garlic” (Anglo-Saxon gar = spear, laec = leek) still shows these connotations.

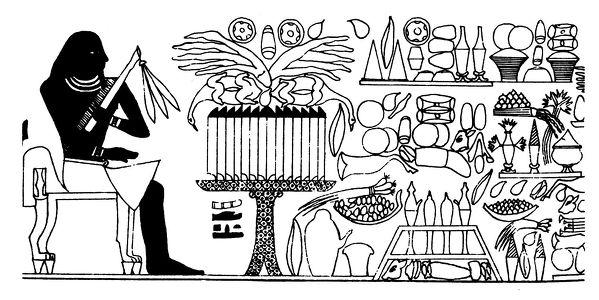

Illustration 47. In ancient Egypt leek numbered among the foods offered to the dead (Egypt, twelfth dynasty)

The old Germanics even had a leek rune (laukr-runa, laguz). This rune had the magic power to dissolve blockage—to melt what is frozen and bring it into flow again. Rune masters carved the leek rune into wooden beams and colored it with sacrificial blood in order to ensure health to the people, as well as prosperity and abundance in the fields. Just as the plant itself, the leek rune protects life fluids from drying out, and safeguards a man’s semen and manly strength. It is also believed to protect mother’s milk from illness so that it continues to flow.

Even the word “leek” was believed to have magical power. It was hammered into coins (bracteates) in order to guarantee the wearer—a traveler or a warrior—preservation of health. Leeks were put into drinks whenever one suspected a vile poison had been secretly put into one’s mead or beer; the leek would either neutralize the poison or indicate its presence. “Put leek green into the drink,” advises the Brunhilde song of the twelfth-century Nibelung Saga. Nobles were honored with leek greens:

A prince was born to his people,

they wished for fortune, golden times.

The king himself left the battlefield

to bring noble leek to the newborn nobleman.

—from Helgi’s Song (“Lay of Helgi Hjörvarōsson”)

The leek is regarded as a noble amidst the vegetation. Gudrún sings: “My Sigurd (Siegfried) was like this, like noble leek rises up high amidst the stalks, like a stag rises up high above foxes and rabbits.”

Nordic warriors carried leeks on their bodies to both protect them from getting wounded and help them vanquish their enemies. It is reported from the Middle Ages that knights and their knaves wore the root of alpine leek (Allium victorialis), also referred to in German as “victory root,” or “any man’s armor,” as an amulet. Well into the sixteenth century in England it was still a sign of provocation to wear a leek on a hat or helmet.

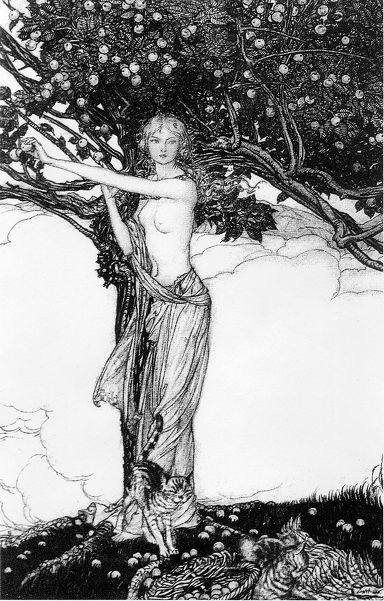

Illustration 48. The beautiful goddess Freya, who gave leek plants to humanity (illustration by Arthur Rackham from a 1910 post card)

Historical records indicate that pre-Roman women folk cultivated fenced-in leek gardens (AS laukagardr) that were dedicated to the fair goddess Freya. Indeed, four major plants were grown in such old Anglo-Saxon gardens: onions (ynne-leac), garlic (gar-leac), chives, and leeks (por-leac). In other areas bear leek (Allium ursinum, or bear’s garlic, ramson) was also included. The women—responsible for health in the home and the barn—considered the leek, no matter which kind, a veritable ally. The saying “flax and leek” was the traditional formula for wishing health and prosperity—referring to the leek as an antiseptic healer of wounds and the use of crushed leaves with a fresh linen (flax) cloth as a bandage. Malicious worms could also be driven off with leek juice, not only intestinal worms but also the invisible “elfen worms” and “spirit worms” that, once settled into organs, suck out one’s life energy. Leek juice was heated in milk and used to dispel so-called “ear worms,” the warm liquid carefully trickled into the infected ear. Leek juice together with the smoke of henbane was used against nibbling, red “tooth worms” that hollow out the teeth (Storl 2000, 109). And in a ceremonial spring meal that lasted even into the Christian Middle Ages, communities feasted on pancakes with fresh leek, believing they’d stay healthy for the entire year.

Leek gardens were also sacred places for the Celts. As leeks’ sulfuric smell reminded the island Celts of the strike of lighting, they were seen as an attribute of Aed (Aeddon), the Celtic “thunderer” and bearer of the lightning bolt; the plant honored him as one of the progenitors of humankind and as a son of the sun. The god possesses a magic spear and his curse can make water dry up and evaporate, but he is also a great healer who can even bring the dead back to life.

In Celtic Britain the leek is revered to this day. As it is the national symbol of Wales, Welsh farmers still observe the custom of eating a meal of leeks together before the spring plowing begins. Each brings a leek to the meal. The symbolism is obvious: leek not only has a phallic form but it is also furthers physical potency; in archaic imagination, plowing was always regarded as a sort of sexual act, as a penetration into the fertile earth to make it receptive for the seeds.

The leek is also the insignia of the famous Welsh Guard, and today still decorates the caps of the Welsh troops. In Shakespeare’s drama Henry V we see that the Welsh fighters placed leek stalks on their helmets in the wars between the English and the French. In one scene an English petty officer who had made fun of the custom was forced to go over to the angered Welsh and eat some leeks. To this day the British say “to eat a leek” for those who have to eat their words.

When the Anglo-Saxons tried to occupy Wales in the sixth century the leek became the identification symbol of the free Welsh. Bishop Dafydd (~500-~589), an ascetic in the tradition of the old druids—he ate nothing but dry bread and vegetables, drank nothing but water, and bathed only in ice water—told the men to wear a leek on their helmets to distinguish themselves from the enemy. At the decisive battle, the Welsh were able to drive off the far more powerful Saxons. After that decisive event Dafyyd, known as St. David today, became the patron saint of Wales. On St. David’s Day, March 1, Welsh still march in parades wearing leeks on their hats.

The leek remained a popular vegetable throughout the British Islands. In Northumberland in northeast England there is an annual contest among male gardeners prizing the biggest, thickest, and longest leek grown in the community. The men spend so much time on the project that the women are pitied as “leek widows.”

In some rural areas in England it is still a custom to let a suitor know whether he is welcomed or not as a son-in-law through the food served to him. If he is served red beets and potatoes, he is not welcome, and might as well leave before eating. Flour pudding and coffee informs him he is desired not as a groom but as a family friend. But if he is served pancakes with leek, then he knows he is welcome.

The Healing Potential of Leeks

In modern times various kinds of these onion-like greens—leek, garlic, or bear’s garlic—are still regarded as good weapons against illness, especially when eaten raw (though with leek only a small amount of the tender inside parts is advised). The essential oils (allicin) mildly stimulate the stomach, intestines, liver, gall bladder, and spleen; they also inhibit putrefactive agents that can cause flatulence, cramps, and diarrhea. The oils also help clear the phlegm of congested respiratory organs. Blended leeks cooked in milk with honey is an excellent remedy for coughing and lung disorders. Leeks also rid the intestines of fungi resulting from bad eating habits. In addition, leeks help reduce cholesterol and lipids in the blood, and their blood-thinning (fibrinolytic) quality benefits worn-out varicose veins.

French traditional healing lore recommends leeks with potatoes cooked in milk as a diet for various kidney ailments. A brew of boiled-out leek seeds is prescribed for urinary ailments; many consider leeks in general good for bladder ailments. Crushed leek bulbs and leaves can be applied for lumbago and gout, and leeks cooked in milk can be applied to abscesses.

These recommendations stand in opposition to statements made by some naturopaths who adamantly claim the leek is “poisonous.” For example: “There are harmful vegetables that should be banned from our tables or at least be eaten only very rarely. One of them is leek (Allium porrum)” (Werdin 1995, 30). Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) is supposed to have declared that the leek is as bad as any poisonous plant when eaten raw because it perverts the blood and the other humors. I find this opinion curious, as I have yet to meet someone who would eat bunches of overpowering raw leeks. Great amounts of raw leek can be poisonous indeed, but the same can be said of beans and potatoes if eaten raw, and neither of those vegetables has earned similar scorn. But, in all fairness, I’ll close by offering a tale of poison. In ancient Rome, Emperor Tiberius accused Mella, an administrator of one of the provinces, of bad bookkeeping and sent for him. Instead of complying, the discredited official committed suicide by drinking a liter of leek juice.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Leeks are raised from seed instead of sets, but otherwise they are treated the same as onions. If the growing season is short they should be sown in a protected place six weeks before planting out into the garden. As they grow they should be hilled up to blanch them, thus keeping the flavor milder. Occasional composting with ripe compost can increase their size. (LB)

SOIL: Leeks flourish in any well-composted garden soil.

Recipes

Leek Pie with Beer Sauce ✵ 4 SERVINGS

LEEK PIE: 2 cups water ✵ 1 teaspoon sea salt ✵ 2 leeks, cut in fine strips ✵ 1 pound (455 grams) pie dough ✵ butter for greasing ✵ 2 eggs ✵ ¾ cup (175 milliliters) cream (18% fat) ✵ 7 ounces (210 grams) cottage cheese ✵ 5 ounces (150 grams) hard cheese, grated ✵ sea salt ✵ black pepper ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ BEER SAUCE: 1 quart (945 milliliters) light or dark beer ✵ 5 ounces (150 grams) arugula (rocket) leaves, finely chopped ✵ 2 bay leaves ✵ some lentil or chickpea flour ✵ sea salt ✵ pepper

LEEK PIE: Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Put the water and salt in a medium pan. Add the leaks and simmer for 20 minutes. Drain well and cool. Roll out the pie dough. Grease a cookie sheet. Place the dough on the cookie sheet, poking holes in it with a fork. Spread the leeks evenly over the dough. In a small bowl, mix the eggs, cream, and cottage cheese; season with salt and pepper. Pour this mixture over the leeks. Cover with the grated cheese and bake at 350 °F (175 °C) for about 1 hour. It should be firm and golden brown on top.

SAUCE: In a medium pan, bring the beer to a boil. Add the arugula (rocket) and bay leaves and simmer for about 20 minutes. Add salt and pepper to taste. Mix in flour in small amounts until you reach a nice sauce consistency. Transfer to a dish; serve with the leek pie.