A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa)

Family: Compositae: composite, daisy, or sunflower family

Other Names and Varieties: salad, greens, leafy greens; butter lettuce, head lettuce, iceberg, leaf lettuce, Romaine

Healing Properties: calms, including sexually calming; increases fertility and milk production; induces sleep

Symbolic Meaning: chasteness, remorse, sleep, fertility; the Virgin Mary; attributes of the phallic gods Min and Adonis

Planetary Affiliation: moon

It takes five minds to create a good salad:

A miser who trickles vinegar,

A spendthrift who pours oil,

A wise person who gathers herbs,

A fool who mixes them,

An artist who serves the salad.

—Jean Anthelme. Brillat-Saravin, 1755-1826

Given the many reasons we today seek lower-calorie foods—to counteract our sedentary lifestyles, to please our partners and appease our doctors—it’s no wonder that vitamin-rich lettuce has earned a prominent role in our diets. Various salad creations complement almost every main meal—or are even the entire meal. And with the many kinds of premixed salads to be found in stores, even the busiest of us have no excuse for not getting our greens.

And there are many varieties to choose from: head lettuce, curly leaf, oak leaf, iceberg, romaine. All belong to the genus lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Another in this family is Chinese lettuce (asparagus lettuce, or celtuce). It first appeared in the 1942 Burpee’s seed catalog, after a missionary brought the seeds from China to the United States; this variety, however, is usually not eaten raw, but cooked like asparagus.

A contemporary author considers the invention of salad “one of the greatest cultural achievements in gastronomy, … a refreshing and healthy side dish to hot dishes” (Mercatante 1976, 195). But such is a contemporary opinion; green lettuce was not always so popular. Even as recently as the pre-World War II era, such “rabbit fodder” was only eaten on Sundays for its cooling effect after a sumptuous roast. Then the lettuce leaves were often soaked for hours in water with vinegar and some sugar producing fairly wilted fare. And the range of salad dressings available to us—balsamic vinaigrette, blue cheese, Caesar, French, honey mustard, Italian, Ranch, Russian, Thousand Island, etcetera—are also relatively modern creations.

It is very likely that Christian monks first brought lettuce from the Mediterranean to the cool northern climates, where they planted it in small cloister gardens. Lettuce is first mentioned in the north in the ninth century when Charlemagne (742-814) decreed it be planted in the land holdings under his rule. Lettuce is also found in the first blueprint of a cloister garden in St. Gallen, Switzerland.

The Health Effects of Lettuce

Lettuce had a reputation for dampening immodest desires, erotic dreams, and consequent nocturnal emissions. As nightly visits from seductive incubi and succubi plagued the poor nuns and monks in the cloisters, there was hardly a cloister without lettuce and some other anaphrodisiac such as dill and chaste tree (monk’s pepper). The monks knew the writings of, for example, Dioscorides (~40-90 AD), who wrote: “Lettuce is good for the stomach, cools a little bit, relaxes, softens the stomach, and helps lactation… . The seeds made into a decoction help those who suffer from involuntary nightly ejaculation and discourage coitus.” Pythagorean philosophers, who tried to avoid dissipating sexual energy but rather to sublimate it, also included lettuce in their diets. In the ancient theory of Humorism, well known to all cloister dwellers, this vegetable plant was categorized as moist and cooling to the third degree: it cools the body as well as the passions.

Illustration 49. Drawing of an incubus (Francis Barrett, London, 1801)

In Christian symbolism, as exemplified in the Renaissance paintings of the Last Supper, lettuce leaves not only represent abstention but also remorse and penance. Except for the tender young leaves, lettuce is a bitter plant; if let grow and mature into seed the plant becomes ever milkier and ever more bitter. The pale yellow blossom was even once seen as a symbol of the chastity of the Virgin Mary.

“Herbal fathers” of the sixteenth century in Europe who drafted the first printed herbals take up the lettuce theme once again, claiming it “diminishes animal drives”: “Lettuce juice spread on the male member reduces immodest desires and blocks [the natural formation of] semen”; also, “All who have vowed to remain chaste should eat nothing but lettuce and rocket” (Piedro Andrea Matthiolus, 1565). Hieronymus Bock (1560) concurred: “Lettuce, eaten regularly, dispels lecherousness.” Seemingly sound advice—except it seems the plant didn’t always comply. A medieval report tells of a poor nun who ate a leaf lettuce upon which an invisible devil happened to be sitting. Because she forgot to make a cross over the salad bowl, the devil was able to enter her body and arouse her desire. It took some doing to exorcise and drive him out of her.

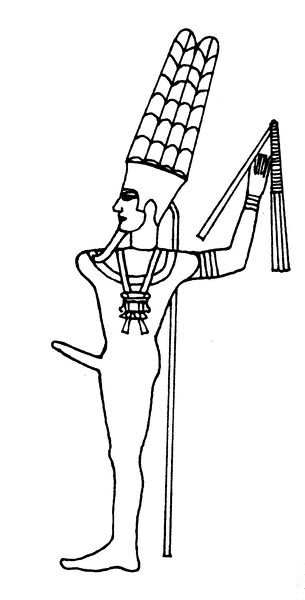

If it is really the case that this delicate member of the composite family actually dampens animal drives, then it’s curious that the ancient Chinese praise it as an aid in fertility: it helps wishes for children to come true. And in the Nile Valley, where leaf lettuce was first cultivated as a garden vegetable, it was even dedicated to Min, the god of sexual fertility and orgiastic rites. Small lettuce gardens in the temples were dedicated to Min: the “bull that satisfies the needs of women and creates seed for gods and goddess,” the “stud that inseminates women with its member.” The Egyptians carried bowls of fresh lettuce plants during sacred processions in honor of this mighty god. Indeed, Christian Rätsch and other modern-day ethnobotanists presume that the milky, white juice of the lettuce is analogous to the ithyphallic god’s milky semen.

In ancient Greece lettuce was dedicated to the phallic, youthful god Adonis. Lettuce seeds were sown ritually into beds called “Adonis gardens.” These gardens, which symbolized the ever-dying-and-resurrecting god, were left to dry shortly after the seed sprouted and turned green. And Aphrodite, the goddess of love, in mourning her lover bedded Adonis’s corpse upon lettuce leaves.

Illustration 50. Min, ancient Egyptian god of fertility; this depiction is from the Fourth Dynasty (2613-2494 BC)

Now how can this contradiction—anaphrodisiac and fertility plant—be resolved? The modern-day genial herbal healer Maurice Mességué assumes that this “plant of the eunuchs” (herbe des eunuques), though it seemingly can dampen sexual desire, simultaneously furthers fertility with its quantity of vitamin E (from the Greek tocopherol, bringing birth). In any case, the Ayurvedic tradition advises pregnant women to eat a lot of lettuce. Indian scientists claim that lettuce beneficially influences the building of pregnancy hormones (progestogens) and helps prevent miscarriages. Ayurvedic teaching also advises nursing mothers to eat plenty of lettuce in order to increase milk flow. Northern Native Americans believed the same; they cooked a tea from the leaves of closely related wild lettuce (Latuca virosa) to keep women’s milk flowing.

Modern research affirms that the folk medicinal use was correct. The white juice in lettuce activates a discharge of prolactin, the hormone that enables female mammals to produce milk. Prolactin can sedate an organism into a dreamy stupor—it correlates to natural body opiates—while simultaneously dampening sexual desires. So when Native Americans give lettuce juice to crying babies to calm them, they are using the same empirical knowledge as Maurice Mességué when he prescribes eating three heads of lettuce in the evening for his patients suffering from insomnia. Since most stomachs can’t hold three heads at once, he suggested cooking them—to lose the watery mass but not the effect. Mességué credits this to the Romans: it was a custom in old Rome to eat cooked and salted lettuce before going to bed. Our word “salad” comes from Italian insalata: salted food (sal = salt). Roman doctor Galen (129-~216 AD) wrote: “When I grew old and wanted to be sure to sleep enough, I found that I was often not able to sleep, often due to simply lying awake at night and other times due to the fact that old people often sleep very little; it was only by eating a dish of cooked lettuce in the evening that I was able to get enough restoring sleep.”

Head lettuce is a milky composite—as are dandelion, chicory, meadow salsify, and sow thistle. It is an annual long-day plant, which means it shoots into blossom when the days become longer than the nights. It has small, pale yellow blossoms, similar to its relatives prickly lettuce (L. serriola) and wild lettuce (L. virosa), with which it can even be crossed. When blossoming it contains the most milk. The dried milk (Lactucarium) was used as a healing means in antiquity. Lactucarium—“cold opium” (opium frigidum)—is a calming but not addictive narcotic. Along with opium, hemlock, and henbane juice, it was included in the so-called “sleep sponges” (spongia somnifera) that medieval doctors used as anesthesia and that henchmen gave to those about to be executed. Pure opium from opium poppies could also be stretched with lactucarium, and many witches’ salves contained sticky, milky lettuce juice. And, not surprisingly, Benedictine abbess Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) did not have good words for “the useless juice of this weed,” claiming “it makes the brain empty and dull.”

Traditional folk medicine knows lactucarium as a cooling, pain-killing, soporific agent, as well as a means for healing infected eyes. Cloth soaked in the juice was placed on the eyes. Legend says that eagles eat lettuce leaves from time to time to keep their eyes sharp. Lettuce leaves, or lettuce juice, were also used in poultices for painful abscesses, as well as for healing the chronic skin infections favus and eczema. Native Americans also used lettuce to alleviate rashes and poison ivy.

Modern medicine has rediscovered lactucarium. Pharmacological research shows that, similar to codeine, it has a calming, inhibitory effect on breathing—but as it is weaker than codeine it is less dangerous. For that reason the juice is used for spasmodic coughs, whooping cough, and asthma. The somewhat inebriating plant was even used as a drug for a time; in the 1970s it was offered in magazines as a legal drug and substitute for hashish. But it soon became clear that the “trip” it induced was boring—in addition to the fact that it tastes awful. The claim that it is a “gateway drug” that “leads to brain damage,” as the FAZ magazine in Germany fabulated, could not have been further from the truth. Thanks to the bitters found in lettuce that further digestion, raw lettuce is ideal for sluggish digestion. In addition, the greens are part of a good alkaline diet, effective in lessening blood acidity. For that reason it is recommended in diets for heart and kidney troubles.

For occultists, plants with white, milky juice stand for something special. The long-lived Dutch herbalist Mellie Uyldert (1908-2009), as well as theosophists and anthroposophists, see these plants as the last representatives of a long-past evolutionary stage on earth—that of Lemuria, a time when the moon had not yet separated from the earth and the earth itself floated like a cosmic embryo in milky fluid, much like an egg yolk in the egg white. They believe that at that time the highest form of consciousness was a sort of dreaming sleep state, and sexuality did not yet exist. Plants like poppy, spurge, and lettuce contain remnants of this milky primeval atmosphere. Like mother’s milk today, this macrocosmic milk helped the young creation to incarnate into the material sphere. For many, such thoughts are surely some kind of “esoteric gobbledygook,” but for these occultists it is surely “fact.”

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: To develop well, lettuce needs warm days and cool nights. All lettuces flourish best in half-shaded areas where the light is filtered during at least part of the day. (LB)

SOIL: Though lettuce needs a well-drained soil, it must be kept moist enough for its quick and succulent growth.

Recipe

Head Lettuce Salad with Honey-Mustard Blueberry-Mint Dressing ✵ 4 Servings

Fresh mint leaves ✵ 1 tablespoon apple vinegar ✵ 4 tablespoons fresh blueberries ✵ 3 tablespoons sesame oil ✵ 1 teaspoon mustard ✵ 1 teaspoon honey ✵ sea salt ✵ black pepper ✵ 1 head lettuce

In a small bowl, mix the mint leaves with the vinegar, blueberries, sesame oil, mustard, and honey. Let stand for 10 minutes, then season with salt and pepper to taste. Prepare the lettuce in a serving bowl. Toss with the dressing and serve.

TIP: This salad pairs nicely with hearty bread.