Real Food: What to Eat and Why - Nina Planck (2016)

Chapter 2. Real Milk, Butter, and Cheese

I AM NURSED ON THE PERFECT FOOD

On the day I was born, at home in our big house on 84 Russell Avenue in Buffalo, New York, my mother and I had everything we wanted. That afternoon she rested comfortably on the couch in our sunny front room, in no particular hurry for anything to happen, with her family checking in occasionally. March 29, 1971, fell on a Monday, but my father didn’t go to work and my sister and brother stayed home from school. The doctor was just taking off her coat when I arrived on a schedule known only to my mother and me. Then my mother fed me the perfect food from the perfect container. Later, she fed herself some real food: mail order organic beef liver from Walnut Acres, one of the pioneering organic brands.

I was a lucky baby. My mother gave me real food in my first hours and nursed me on demand until I stopped asking for fresh raw milk three years later. If possible, a woman should nurse exclusively for at least one year, or longer if it suits both parties. Though it’s uncommon today among working women, nursing longer than the usual six or twelve months is natural. In modern hunter-gatherer societies, nursing for three years is typical and four to six years is not unheard of. UNICEF and the World Health Organization advise breast-feeding for “two years and beyond.”

Breast-feeding cements a profound bond between mother and baby. When things are going well it’s a very nice sensation. Some mothers describe loving, trancelike feelings when nursing, and babies will suckle long after they are full. In Fresh Milk: The Secret Life of Breasts, Fiona Giles collected memories of nursing from young children. “It was comforting and relaxing,” said an eight-year-old boy. “I looked forward to it.” A twelve-year-old girl was more blunt: “The word addictive comes to mind.” An older sibling who had been weaned acted out her own farewell as she watched the new baby nurse. She would cover her mother’s breasts and say, “Bye bye, delicious milk.”

Breast milk is our first food, the best food, the ultimate traditional food in all cultures without exception. That’s why nature made nursing satisfying: to encourage mothers and babies to do it.

Because it was designed as the baby’s only source of food, breast milk is a complete meal. If the mother is well nourished on real food, her breast milk will contain just the right amount of protein, fat, carbohydrates, and all the other nutrients for the growing baby, including essential vitamins, with one notable—and interesting—exception. The milk of all mammals lacks iron. Moreover, milk contains the protein lactoferrin, which ties up any random iron that does find its way into the young. There is logic in the missing iron: iron is necessary for the growth of E. coli, the most common source of infant diarrhea in all species. A breast-fed baby rarely needs any additional iron before one year; bottle-fed babies may need iron sooner because infant formula depletes iron. After one year, iron-rich raw liver is often a first solid food for babies in traditional diets.

Breast milk is not only a complete meal but also a rich one: about 50 percent of its calories come from fat. Indeed, fats may be the most important thing about breast milk. At the most basic level, fat is essential for the baby’s growth and development, and for assimilating protein and the fat-soluble vitamins A and D, but each particular fat in breast milk also plays an important role.

The long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fats EPA and DHA in mother’s milk are vital to eye and brain development in the baby. Pregnant and nursing women should eat plenty of fish—the only source of fully formed EPA and DHA—and keep eating it. With each pregnancy, a woman’s store of omega-3 fats is depleted. The hungry baby neither knows nor cares whether her mother eats wild salmon, but simply takes the omega-3 fats she needs to build her own brain.

As we saw earlier, vegans and vegetarians risk deficiency of EPA and DHA. The breast milk of vegan mothers contains less DHA than nonvegan breast milk.1 Nursing mothers who do not eat fish might take a supplement of flaxseed oil, which contains a precursor fatty acid called ALA. The body can make EPA and DHA from the ALA in flaxseed oil, but the conversion is uncertain and imperfect. It bears repeating: fish is vastly superior to plant sources of omega-3 fats.

Most of the fat in breast milk is saturated. The body needs saturated fat to assimilate the polyunsaturated omega-3 fats and calcium. Mother’s milk is a rare source of a saturated fat called lauric acid. Antimicrobial and antiviral, lauric acid is so critical to the baby’s immunity that it must, by law, be added to infant formula; the usual source is coconut oil.

The ample cholesterol in human milk is essential to the developing brain and nervous system. So vital is cholesterol, breast milk contains a special enzyme to ensure the baby absorbs it fully.2 Humans make cholesterol in the liver and brain, but infants and children do not make enough cholesterol for health. Thus the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics says the diets of children under two must include cholesterol.3

Many other factors in breast milk boost the baby’s immunity, an essential shield in its new, germ-filled world. White blood cells, sugars called oligosaccharides, and lactoferrin fight bacteria and viruses. (Lactoferrin from human milk is patented for use in killing E. coli in the meatpacking industry.) Mother’s milk contains all five of the major antibodies, especially IgA, which is found throughout the human digestive and respiratory systems and protects tissues from pathogens.4 Babies don’t begin to make their own IgA for weeks.

In one of nature’s many elegant efficiencies, the antibodies in breast milk are targeted to the pathogens in the mother and baby’s immediate environment; they are tailor-made for the baby. Dr. Jack Newman, a breast-feeding consultant to UNICEF, says researchers can’t explain “how the mother’s immune system knows to make antibodies against only pathogenic and not normal bacteria, but whatever the process may be, it favors the establishment of ‘good bacteria’ in a baby’s gut.”

BREAST MILK: A COMPLETE MEAL

✵Complete protein and carbohydrate (for growth)

✵Saturated lauric acid (to fight infection)

✵Polyunsaturated EPA and DHA (for the brain and eyes)

✵Cholesterol (for brain and nerves)

✵Many immune factors (to fight infections)

✵Beneficial bacteria (for digestion)

Breast milk is the most important food a mother will ever feed her baby. A convincing number of studies suggest that babies who drink this perfect food tend to have better immunity and digestion, lower mortality, and higher IQ than formula-fed infants. They typically have lower rates of hospital admissions, pneumonia, stomach flu, ear and urinary tract infections, and diarrhea than bottle-fed babies. In later life, breast-fed babies often have lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and extra protection against juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, allergies, respiratory infections, eczema, immune system cancers such as lymphoma, Crohn’s disease, diabetes, stroke, and heart disease. Breast-fed babies are less likely to be obese when they grow up, possibly because breast milk is rich in the protein adiponectin. Adiponectin lowers blood sugar and affects how the body burns fat. Low levels of adiponectin are linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.

Some women find that breast-feeding is not as easy as it looks in those lovely paintings of Madonna and Child. For many understandable reasons, mother and baby may find nursing difficult, painful, or in extreme cases impossible. If nursing isn’t right for you and your baby, choose a formula with care, ideally an organic cow-milk version. Even with the best intentions, it hasn’t been easy for scientists to duplicate the properties of breast milk, which contains more than three hundred known ingredients and probably still more yet to be identified. Most formula contains a mere forty ingredients, and often the main ingredient is sugar. In the United States, most infant formula contains no long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fats, an unconscionable omission given their vital role in the eyes and brain. The World Health Organization and the European Union both recommend omega-3 fats for babies; infant formula with DHA is widely available in Europe and Asia.

Soy-based formula and low-fat diets are particularly unwise for babies and children. As we’ll see later, soy lacks adequate methionine and is far too rich in estrogens. Low-fat diets cause stunted growth, learning disabilities, interrupted sexual development, and the syndrome seen in the babies of malnourished vegan and vegetarian mothers, “failure to thrive,” which is marked by slow growth and lethargy.5

The best homemade substitute for breast milk is made from grass-fed, raw whole milk, supplemented with live yogurt cultures and gelatin (for digestion), coconut oil (for immunity), and cod-liver oil (for the eye and brain).6There are also human milk banks for special cases, such as premature babies and those who are allergic to formulas. Throughout history, women, including wet nurses, have provided milk for infants whose own mothers were unwilling or unable to do so. At the Mother’s Milk Bank in Austin, Texas, potential donors are carefully screened with blood tests, and donated milk is pasteurized and tested before being fed to babies.

Traditional societies provide advice and assistance to nursing mothers, usually from older relatives or experienced local women. The contemporary equivalent of this support network is La Leche League, an excellent and friendly source of practical and scientific knowledge about breast-feeding. If you are nursing and run into difficulty, or if you feel lonely or discouraged, try calling these modern-day wise women. They know all about cracked and tender nipples—and your baby will thank you one day.

I REMEMBER MILKING MABEL THE COW

In 1973, when I was two years old, we moved to the Newcomb farm in Fairfax County, Virginia, and thus began our relationship with a long line of family cows. We had a red and white Hereford named Katy, a gentle black Angus called Steady Teddy, and the milk cows: a Guernsey named Emma, who slipped out one evening and was never heard from again, and a Jersey called Tai Tai—an honorific akin to “Mrs.” in Mandarin. Later, when we moved to our own farm in Loudoun County, we bought Mabel, a chocolate-colored Jersey. I’m afraid her character didn’t conform to the stereotype of the docile cow. As my brother, Charles, remembers, “Mabel was often irritated with us.”

By then I was nine or ten, and milking was one of my regular chores. On my night to milk, I’d bring Mabel into the barn from the pasture, put her in the stanchion, and give her a little grain while I washed her udder. Then I’d sit on a wooden stool my brother had helped me build and begin to milk, making a ring with my thumb and forefinger and squeezing the teat from the top down, one finger at a time, first one hand, then the other.

There is a pleasant, lulling rhythm to milking. Even now the sounds are vivid: Mabel’s noisy chewing and breathing, the soft rustling as the chickens settled in for the night. At first, when the bucket is empty, the milk goes “ping” as it hits the tin. As the pail fills up, each squirt meets the foamy liquid and the pitch drops. In the summer, her tail—called a switch in dairy lore—might miss the flies on her flank and sting my face. With Mabel, there was also a good chance she’d lose her poise and kick the bucket over or step right in it. You had to whisk the bucket away.

Before long her bag was loose and empty, and there were a couple of gallons of milk. If she’d been scratched by brambles, I rubbed her udder with a miraculous salve called Bag Balm, made in Lyndonville, Vermont, since 1899. (I still use it on my own cuts and scratches.) I carried the milk across the footbridge to the house and strained it through a striped pink cloth into glass gallon jars. We wrote the date, plus am or pm, on masking tape and stuck it to the jar. That was it.

Going to school smelling of cow was mortifying, and when I had to milk in the morning I always took my shower afterward. I knew we weren’t supposed to sell raw milk—after we put an ad in the paper, two friendly women from the state came around to tell us to keep it quiet—but was ignorant about why it was better than supermarket milk. The jars of milk in the fridge were like the wheat berries on the shelves: embarrassing.

Eventually the burden of daily milking grew tedious, and we sold Mabel to a local man, luring her into his truck with sweet corn, and we never kept a cow again. It seems sad now. Having visited dairy farms small and large, tasted industrial and real milk side by side, and learned a bit about how butter and cheese are made, I begin to grasp that having more fresh milk and cream than we could drink was a luxury.

Historically, milk was more than a luxury; it was critically important in the diet. For peasants, the cow kept the grocery bill down and the doctor away. With her ability to convert inedible grass into milk and cream, the cow was at the center of the domestic economy. Rich in protein, fat, calcium, and B vitamins, milk was known as “white meat,” capable of transforming an inadequate diet of bread and potatoes into a passable one, especially for children. In cucina povera (peasant cooking), vegetables are often soaked in milk before roasting.

A cow needs nothing more than a patch of grass, but most European peasants were too poor to own land, and for centuries they grazed animals on common land. In Britain and elsewhere, the gradual loss of access to the commons in the late eighteenth century was catastrophic for peasants, who were no longer able to keep cattle for milk and meat. The British historian J. M. Neeson describes “the stubborn memory of roast beef and milk” and their “swift disappearance” from the diet of the poor after the loss of grazing rights.7 In 1786, the cleric H. J. Birch wrote that butter was too dear for his Danish parishioners. They made do with bread crusts, beer, and cabbage boiled without meat. When “cottagers receive not the smallest patch of land or grazing for cows or sheep, and are not even entitled to keep as much as a couple of geese on the common … then poverty and need reach dire extremes; then cottagers begin to beg—people who have never begged before, and never thought of begging.”8

In the New World, too, milk was a staple, from the earliest colonial days right through the middle of the twentieth century, when farmers like my great-aunt Esther still kept a cow in Milford, Illinois. Esther and Uncle Charlie mostly raised crops, but they most likely made a little extra money selling milk and cream. Initially, colonial Americans preferred goats, probably because they were rugged and good at clearing land, and by 1639 there were four thousand goats in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. But the cow—a superior milker—gradually replaced goats. In addition to pulling the plow, oxen also provided manure for crops, beef to eat, tallow for candles, and leather to wear.

Though grazing was allowed on public sites like Boston Common, the European model of using common land for grazing wasn’t widespread. The self-sufficient homestead was the original American dream and became the typical farming pattern. In 1626, each family in the Plymouth Colony was allotted one cow and two goats for every six shares of land they held. “This ideal characterized small farming in America for another two centuries,” write Annie Proulx and Lew Nichols in The Complete Dairy Foods Cookbook.

JERSEY, QUEEN OF COWS

I’m charmed by the colorful names of breeds, suggesting their hometown (Kerry) or looks (Dutch Belted) or qualities (Milking Devon). Others known for milk, meat, or both include the Hereford, Simmental, Limousin, Angus, Brown Swiss, Ayrshire, Milking Shorthorn, Norwegian Red, and Holstein-Friesian. The star of the industrial dairy is the Holstein, a Dutch cow known for copious production of low-fat, watery milk. For small dairies, the undisputed champion is the Jersey, a small cow native to the Channel Islands. Docile, an efficient grazer even on poor pasture, intelligent, and productive, she is also the ideal family cow. But the Jersey’s crowning glory is her milk: it contains the highest level of protein, minerals, vitamins, and butter-fat of any breed. Jersey milk is 5 to 6 percent butterfat, nearly twice as rich as Holstein milk, with 3 to 3.5 percent fat—the norm for whole milk. Jersey milk (and that of her cousin, the Guernsey) is too rich for some to drink straight. No matter; there will be plenty of fat for cream, butter, and cheese.

Today the family cow is rare, but her role is the same. “The cow is the most productive, efficient creature on earth,” writes Joann Grohman in Keeping a Family Cow. “She will give you fresh milk, cream, butter, and cheese, building health, or even making you money. Each year she will give you a calf to sell or raise for beef.” The cow also provides manure for the garden, sour milk for the chickens, and skim milk or whey for the pig—milk-fed pork being a delicacy. “I serve exceptionally fine food”—I can confirm this, having eaten at Joann’s house—“and I am not stingy with the butter and cream,” says Grohman. “The cow is a generous animal.”

Keeping a Family Cow inspired Laura Grout, a mother of five, to change her life. “I was living in a trailer park with a postage stamp for land and researching nutrition. After learning that unpasteurized milk is better for your health, I went looking for a legal way to obtain raw milk. This book alone convinced me to leave the city and have a cow.” Laura began to raise her own beef, milk, poultry, and eggs in Sand Hollow, Idaho. “Good nutrition is something every mother should strive to give her children,” she says, “no matter how rich or poor.”9

That was my mother’s philosophy in a nutshell. She used to say, “No matter how little money we spend on food, we will always have maple syrup, olive oil, and butter.” Now that I live in the city and pay good money for real milk and cream, the significance of a cow is tangible: Mabel made us richer. I loved a bowl of milk and mashed-up peaches; we put milk on hot oatmeal, and dessert was often vanilla pudding or custard. After school, Charles and I made smoothies with raw milk, eggs, coffee, and honey. With Mabel, milk was free and life was good.

A SHORT HISTORY OF MILK

Over thousands of years, humans have herded, corralled, and milked a variety of mammals. In the Near East, our ancestors domesticated sheep and goats about eleven thousand years ago; archaeologists surmise that milk, not meat, was the initial reason for keeping animals. The first shepherds tended sheep and goats, small and easy to handle. They are also rugged: they thrive on poor farmland and don’t mind harsh climates. Sheep tolerate cold, wind, and snow, while goats scamper up the steepest mountain and live off brambles or any weed that happens to grow in hedgerows. On the rocky slopes of Greece and the hills of hot, dry Provence, sheep milk cheese (salty, crumbly feta) and goat milk cheese (creamy chèvre) have been made since ancient times.

About eighty-five hundred years ago, somewhere in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), we began to milk the larger and more productive cow. Cows are more delicate than sheep and goats—in bad weather they prefer the barn, and for grazing they favor lush rolling pasture—yet of all the mammals humans have tried, including asses, buffalo, camels, llamas, mares, reindeer, and yaks, the cow is the champion milker.

That’s the conventional chronology of milking, at any rate, but several clues suggest we were drinking milk for much longer than ten thousand years. One clue lies in the popular understanding, or misunderstanding, of early agricultural history. Most people believe that “farming” (meaning both plant and animal husbandry) began about ten thousand years ago in the Fertile Crescent. It is more likely, however, that we herded animals long before we grew corn, wheat, and beans. There is no agricultural reason to link milking with growing grains. The natural diet of ruminants is grass. Early shepherds didn’t need to grow grain: they needed only meadows and some skill in handling animals.

Fences imply that we were shepherds before we were farmers. “Thirty thousand years ago, people in the High Sinai were confining and breeding antelope with the aid of fences, a human invention arguably as important as the spear,” writes Grohman in Keeping a Family Cow. Fences were the best means of keeping the best milkers close at hand and choosing the most docile and productive cows to mate. The friendly, efficient dairy cow has been the focus of so much intensive breeding over thousands of years that today she has no wild cousins left, and lives only at our whim.

All meat and dairy cattle are descendants of the original wild ox, a six-thousand-pound giant called an aurochs, described by Julius Caesar as only slightly smaller than an elephant. “The aurochs became extinct in the seventeenth century, the last one dying alone in a private park in Poland,” writes Gina Mallet in Last Chance to Eat. “But it can be seen depicted in cave paintings: a large, bony animal with sharp horns impaling stick humans.” How the fierce aurochs—a symbol of strength in Viking runes—was eventually domesticated is a mystery. In A Cow’s Life, M. R. Montgomery suggests that Neolithic man tamed an aurochs midget first.

In time we were master of bull and cow alike. Fish and game made up most of the typical Paleolithic diet, but this new food, milk, had its advantages and before long it was popular. As a source of daily protein, milking wild ruminants was more reliable than hunting, which was hit-or-miss. Hunting also presented a practical problem. Because it was impossible to keep meat fresh without refrigeration, fresh kill had to be eaten quickly. The immediate family of the successful hunter couldn’t eat a wooly mammoth in one sitting, so the bounty was shared with the tribe or village. Thus sharing meat with other men—or trading meat (dinner) for sex with a woman—is one of the oldest human activities. Even now, serving a roast is a symbol of hospitality. Milking, by contrast, did not present the feast-or-famine dilemma; it was a steady business.

Technology plays a big role in the history of milk; every advance in fencing, breeding, and preserving milk made milking more efficient. The result is that consumption of dairy foods is nearly universal in human groups. With the notable exception of East and Southeast Asia, all the European and Middle Eastern cultures, and many Asian and African ones, have a shepherding tradition.

Yogurt, the simplest form of preserved milk, is probably as old as milking itself. Milk “invites its own preservation,” writes food maven Harold McGee. Fresh milk curdles quickly, especially in hot weather. Yogurt would have been made—or rather, made itself—simply for lack of refrigeration. The precise origins of yogurt are not known but easy to imagine. When fresh milk is left to stand at room temperature, local bacteria begin to consume the sugars. The milk thickens and becomes tangy with lactic acid. Depending on the bacteria, the result is yogurt, sour cream, or some other cultured milk that stays fresh longer than “sweet” or fresh milk.

Another simple method of preserving nutrients in milk is to remove water. In Iran, milk was reduced to its essence, making a sort of milk bouillon cube to be reconstituted with water. In the thirteenth century, the nomadic Tatar armies of Genghis Khan carried a packed lunch of powdered mare’s milk. After skimming off the cream for butter, they dried the skim milk in the sun. Kept in a leather pouch, powdered milk made a convenient meal on the road. It wasn’t perishable, and when mixed with water and jostled about on horseback, it made a fermented drink something like yogurt.

Turning milk into cheese is the most sophisticated method of preservation. Gouda, Parmigiano Reggiano, and other traditional aged cheeses mature for two years or longer. Most agree that cheese making is about five thousand years old, but as with yogurt, no one knows exactly where cheese was born, and it’s quite possible that shepherds living far apart invented cheese simultaneously. Some of those pioneers were in the French Pyrenees, and in Sumeria, Egypt, five-thousand-year-old pottery bears cheesy residues. Though cheese takes many forms, the basic method—adding rennet to curdle milk—is unchanged, and even particular recipes survive a long time. The recipe for Gaperon, a soft French cheese made with garlic and peppercorns, is twelve hundred years old.

The effects of milk on human diet and culture were widespread and profound. In About Cows, Sara Rath says that six-thousand-year-old Sanskrit writings refer to milk as an essential food. The Hindus, who ate and celebrated butter four thousand years ago, honor cows, as did the Sumerians and Babylonians. The Romans, too, were milk drinkers and cheese lovers, and spread the habit throughout Europe. Cattle—in Latin pecus, from pascendum (put to pasture)—were even used to conduct trades; hence the Roman word for money, pecunia. Caesar was evidently irritated to find that Britons in his far-flung empire neglected to grow crops, preferring to live on meat and milk instead.

The Bible makes dozens of references to milk, which represents privilege, wealth, and spiritual blessings, as in “land flowing with milk and honey.” Shakespeare’s plays are replete with flattering comparisons to milk, butter, and cream, and modern idioms glorify milk. To flatter someone, you butter him up; the very best is la crème de la crème.

Whether from the human breast or the bovine udder, milk is the universal perfect food—delicious, soothing, nourishing. Milk is delicate, sensuous, transient. It is both simple—a nutritionally complete meal in a glass—and marvelously complex, its various ingredients interacting as if the milk itself were a tiny ecosystem. Indeed, traditional milk is alive, teeming with enzymes and microorganisms that evolved right along with man and woman, usually in the belly.

Milk is diverse. The milks of the ewe and the cow, the mare and the nak, are each different. Even within one species, milk is suggestible: the grass, flowers, and herbs the animal eats create further distinctions, affecting aroma, flavor, and nutrition. The hint of garlic—or more than a hint—in milk is not unknown when animals eat their way through a patch of wild ramps. Gracious and malleable, milk is capable of being transformed into cloudlike whipped cream, silken butter, wobbly yogurt, tangy kefir, creamy fromage frais, fluffy ricotta, and dense cheddar.

No wonder this noble food has inspired farmers, chefs, poets—and even politicians. William Cobbett was a member of Parliament, pamphleteer, and reformer who toured the English countryside in the early nineteenth century. A self-appointed defender of farm life and the working man, Cobbett understood peasant life better than most politicians. “When you have a cow,” he wrote, “you have it all.”

I REPLY TO THE MILK CRITICS

We are the only animal to drink milk after weaning and the only animal to drink the milk of another mammal. Whether that’s good is a hot topic. Some say milk is a cure-all. In the nineteenth century, doctors credited all-milk diets with all manner of therapeutic effects, and even today modern practitioners treat maladies from arthritis to eczema with whole raw milk. The other side says milk is poison.

Robert Cohen is one of milk’s fiercest critics. The milk carton on the cover of his book, Milk: The Deadly Poison, bears a skull and crossbones, with the ingredients listed in large type: “Powerful growth hormones, cholesterol, fat, allergenic bovine proteins, insecticides, antibiotics, virus, and bacteria.” Cohen says dairy foods are linked to acne, allergies, anemia, asthma, constipation, obesity, osteoporosis, and breast cancer. “It is probable,” writes Cohen, “that milk consumption is the foundation of heart disease.”10 People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals runs a campaign against milk called Milk Sucks! “Dairy products are a health hazard … laden with saturated fat and cholesterol. They are contaminated with cow’s blood and pus and frequently … with pesticides, hormones, and antibiotics.”

Press like that could make a vegan out of the most contented milkmaid, and that’s exactly what happened to me. I gave up dairy foods to avoid saturated fat and cholesterol and because they were said to be indigestible and allergenic. It was soy drinks for me. Later, when I was working with small dairies at the farmers’ markets in London, I began to wonder about the bad reputation of milk, cream, butter, and cheese. Our customers were snapping up whole milk and raw milk cheese. As I began to eat real dairy again, it was easy to see why. Soy drinks taste nothing like the real thing. In cooking, butter is irreplaceable. As for cheese, I had barely begun to discover the most complex and diverse form of the remarkably pliable milk.

But I was astounded that people could thrive on the rich dairy foods I thought were indigestible and allergenic. Why weren’t butter and cheese lovers plagued with acne, stuffy noses, and stomach cramps? Even more startling, I felt better as I nibbled my way back into real milk, butter, and cheese. Slowly it dawned on me that milk might not be so bad. I began to read more systematically, hoping to uncover the real story of milk—or, more precisely, the whole story. Milk is a complex food, and so are the arguments around it. The critics and the enthusiasts both make good points; the truth about milk seems to fall between the two extreme positions.

What I learned is that all milk is not created equal. Some milk is better than others—for the cow, the environment, and human health. Modern industrial milk is not the same as the milk we used to drink ten thousand years ago—or even one hundred years ago. Not only is traditional milk from cows raised on grass, without synthetic hormones, more delicious than industrial milk from cows raised indoors on corn and soybeans; it’s also better for you. Some forms of milk, such as yogurt, are easily digestible—even for people who think they are lactose intolerant. Nutritionally, raw milk has many advantages over pasteurized milk. Now, when people ask, “Is milk is good for you?” I’m likely to answer, “That depends. Which milk?”

The milk critics make three broad charges. They say that milking is inhumane for cows, dairies pollute the environment, and milk is unhealthy. About the first two, they are absolutely right, with one qualification: industrial dairies are bad for cows and for the environment, but traditional dairy farming is good for both.

According to Jo Robinson, the author of Pasture Perfect, when farmers graze dairy cows outside on their natural diet of grass, the cows are happy and healthy. Farmers who switch from confinement dairies and a grain-based diet and let their cows roam outside eating grass watch their vet bills shrink. One reason is that eating grain gives cows the bovine version of acid indigestion, which can lead to stomach ulcers. Large confinement dairies also pollute the environment with stench and manure lagoons. Properly managed grazing, by contrast, enhances soil fertility, water quality, and biodiversity. Another reason cows on pasture thrive is the rich pharmacopeia in the grasses and forbs they eat.

The question of health is more complicated. First, the critics contend that humans are not meant to drink the milk of any other species. Second, they say that milk is indigestible for people who don’t make enough of the enzyme lactase to digest the sugar lactose. Let’s look at each argument.

Is drinking milk unnatural? The critics say that cow milk was “designed” for newborn calves, not for humans. That’s true. But this observation does not prove that the human digestive system cannot, or should not, handle milk. After all, the tomato was designed to make more tomato plants, not pasta sauce. In fact, milk and other dairy foods are not only digestible for the vast majority of people—about 85 percent by some estimates—but also highly nutritious. Later, we’ll look at important differences between traditional and industrial milk, but for now let’s consider its basic components.

Like breast milk, the milk of cows and other mammals is nutritionally complete. All milk is made of the three macronutrients—protein, fat, and carbohydrate—and humans are equipped to digest all three. A good source of complete protein, milk contains all the essential amino acids in the right amounts. Milk contains enough carbohydrates for energy and has a good balance of fats, both saturated and unsaturated.

Because it was made to be the only source of nutrients for growing babies, milk contains everything required to digest and use its nutrients. The fats in milk, for example, enable the body to digest its protein and assimilate its calcium. According to Mary Enig in Know Your Fats, the saturated fats in milk (such as butyric acid) are particularly easy to digest because they do not have to be emulsified first by the liver. Unlike polyunsaturated fats, which the body tends to store, the saturated fats in milk are rapidly burned for energy.

Milk is rich in vitamins and minerals. It contains potassium and vitamins C and B, especially B12, which is found only in animal foods. Milk is the major source of the fat-soluble vitamins A and D in the American diet. As Weston Price observed more than seventy years ago, the calcium and phosphorus in milk are particularly important for handsome facial structure and strong teeth. Dairy foods also reduce oral acidity (which causes decay), stimulate saliva, and inhibit plaques and cavities.

GOOD THINGS IN MILK

✵Complete protein to build and repair tissues and bones

✵Vitamin A for healthy skin, eyes, bones, and teeth

✵Vitamin D to aid calcium and phosphorus absorption and for bones and teeth

✵Thiamine to help turn carbohydrates into energy and aid appetite and growth

✵Riboflavin for healthy skin, eyes, and nerves

✵Niacin for growth and development, healthy nerves, and digestion

✵Vitamin B6 to build body tissues, produce antibodies, and prevent heart disease

✵Vitamin B12 for healthy red blood cells, nerves, and digestion; and to prevent heart disease

✵Pantothenic acid to turn carbohydrates and fat into energy

✵Folic acid to promote the formation of red blood cells and prevent birth defects and heart disease

✵Calcium to make strong bones and teeth; also aids heartbeat, muscle, and nerve function

✵Magnesium for strong bones and teeth

✵Phosphorus for strong bones and teeth

✵Zinc for tissue repair, growth, and fertility

✵CLA in organic and grass-fed milk

Critics charge that milk is indigestible for people who don’t make enough of the enzyme lactase to digest the lactose in milk. This important argument deserves a full discussion. Lactose plays a large role in the history of milk.

The milk sugar lactose is found in no other food—unless you eat yellow forsythia blossoms in the spring. Without the enzyme lactase, drinking milk causes nausea and diarrhea. Raw milk contains lactase, but the enzyme is damaged by pasteurization. Babies, who drink nothing but milk, produce a lot of lactase; this declines steadily until they reach the age of three or four, and then levels off. The logic of this efficiency is clear. Stone Age mothers probably nursed babies for two or more years. Unless the child drank milk after weaning, lactase production gradually tapered off. The result is that some adults lack sufficient lactase to digest fresh milk easily. The condition is often known as lactose intolerance; low lactase production is more precise.

Climate partly explains the evolution of lactase production. Active lactose genes are most common in people whose ancestors came from cold climates. In hot places, where fresh milk could not be kept cold, fewer adults developed the capacity to produce lactase, simply because they didn’t drink fresh milk. Genetic analysis shows that milk proteins in seventy European cattle breeds evolved along with human genes for lactose tolerance near northern European dairy settlements in the last eight thousand years, a rare example of cultural and genetic coevolution between humans and another species.11 The genes show that early northern European shepherds were dependent on milk. A large majority of Dutch and Swedish people produce plenty of lactase, thanks to their ancestors’ intimate partnership with cows.

The European mutations are well known, but recent evidence suggests that drinking milk has been compelling for other human tribes too, even in warm places. It turns out that the gene that produces lactase also evolved independently in at least several African peoples. In 2006, Sarah Tishkoff of the University of Maryland and colleagues reported that among forty-three ethnic groups of East Africa, three new mutations—independent of each other and of the European mutation—arose to keep the lactase gene switched on. One mutation, found in Nilo-Saharan-speaking ethnic groups of Kenya and Tanzania, probably appeared 2,700 to 6,800 years ago, neatly matching the era when pastoral tribes reached northern Kenya. (The first pastoral tribes arrived in north-western Sudan about 8,000 years ago, making African dairy culture nearly as old as European dairy ways.) Every mutation favoring the active lactase gene conferred a significant advantage: more food, more calories, and more liquids in a drought meant higher survival rates and more descendants.

Even in hot climates, adults with low lactase production didn’t forgo dairy foods entirely. After all, Italy, Greece, and Israel are but three sunny countries with dairy traditions. Instead they ate cultured or fermented milk products, particularly yogurt, which is easy to digest because it contains little (if any) lactose. Beneficial bacteria have already consumed the lactose and turned it into the lactic acid that imparts the distinctive tangy taste to yogurt. Thanks to these tiny bacteria, almost everyone can digest cultured milk. In cheese making, lactose is also transformed into lactic acid, but more slowly. The longer the cheese has been aged, the less lactose it contains.

This “solution” to the problem of drinking fresh milk was no doubt accidental. Recall that fresh milk left to stand overnight rapidly becomes yogurt with the help of whatever bacteria happen to be about. Quite by chance, shepherds devised many local variations on yogurt—the word is Turkish—including Armenian matzoon, Bulgarian naja, Egyptian laban, and Balkan kefir, traditionally made with fermented mare milk.

TRADITIONAL AND INDUSTRIAL FOOD WAYS

Yogurt and cheese are processed foods. Processed foods have a bad reputation, often justified. But industrial and traditional methods are different: industrial food processing diminishes flavor and nutrition, while traditional food processing enhances both. When whole wheat is refined into white flour, flavor, fiber, and B vitamins disappear. Cold-pressed olive oil keeps its vitamin E and antioxidants. When grape juice turns into wine, antioxidants form. When cabbage becomes kimchi, the result is more vitamin C, enzymes, and good bacteria. Fermented foods like sauerkraut, cheese, and yogurt are among the oldest and most nutritious processed foods. Yogurt is widely associated with longevity.

Traditional cultured milks are not only digestible but also nutritious. According to Harold McGee, beneficial bacteria found in “traditional, spontaneously fermented milks” take up residence in our guts and promote health all over the body. The bacteria secrete antibacterial agents, enhance immunity, break down cholesterol, and reduce carcinogens. The bacteria added to industrial yogurt don’t necessarily do the same good work. They’re specialized to grow in milk only and can’t survive inside the body. Moreover, industrial yogurt may contain only two or three selected microbes, while the traditional version may sport a dozen or more friendly bacteria. “This biological narrowing may affect flavor, consistency, and health value,” writes McGee.

Cultured foods are vitally important in traditional diets. In some cultures, yogurt is the only form of milk consumed. When versatile milk is transformed into yogurt and cheese, people all over the world can eat dairy foods—and given how practical, delicious, and nutritious milk is, most do.

Milk is also rich in cholesterol and saturated fat. Does that mean the shepherds and dairy farmers who drink whole milk daily have high cholesterol and heart disease?

MILK, BUTTER, CHOLESTEROL, AND HEART DISEASE

Let’s recall the gist of the cholesterol theory of heart disease: eating cholesterol and saturated fat raises blood cholesterol and clogs arteries. If so, the milk critics have a case, because milk is rich in cholesterol and saturated fat. Milk is 87 percent water; the rest is protein, fat, and lactose. An eight-ounce (250 ml) glass of whole milk (typically 3.5 percent fat) contains about 9 grams of fat, most of it saturated—about 66 percent. About 30 percent is monounsaturated, and there’s a bit of polyunsaturated fat, too. The typical glass also contains about 35 milligrams of cholesterol, mostly in the fat. (By the way, I never count grams of fat, cholesterol, protein, or anything else—nor do I recommend it—but I offer these figures for complete information.)

This nutritional profile has been enough to indict milk on charges of causing heart disease, but abundant evidence exonerates real milk, butter, and cheese. Many traditional diets include whole milk and butter without adverse effects. In Swiss dairy and Masai shepherd communities, Weston Price found people eating whole milk, cream, and butter to be in excellent health. In the 1960s, long after Price studied the Masai diet, Professor George Mann went to Kenya to test the hypothesis that a diet rich in saturated fat and cholesterol raises blood cholesterol.12 The Masai are almost pure carnivores, eating mostly milk, blood, and meat. A Masai man drinks up to a gallon of whole milk daily, and on top of that he might also eat a lot of meat containing still more saturated fat and cholesterol. Mann expected the Masai to have high blood cholesterol but was surprised to find it was among the lowest ever measured, about 50 percent lower than that of the average American.

Like the Swiss and Masai diets, the traditional American diet was once rich in whole milk, cream, butter, and meat. At the turn of the last century we ate plenty of butter and other saturated fats. The Baptist Ladies Cookbook (1895) and The Boston Cooking School Cookbook (1896) include recipes for creamed liver, lamb fried in lard, creamed fish, and oyster pie with a quart of cream and a dozen egg yolks. About 40 percent of the calories in these menus come from fats, with slightly more saturated than unsaturated fats. An English Jewish cookbook in 1846 is similar, but it calls for beef fat instead of lard. These menus would be unremarkable—after all, everyone’s great-grandmother cooked that way—except for one curious, highly relevant fact. In 1900, when these recipes were used and saturated fat was a regular part of the diet, heart disease was rare. The first case of heart disease as we know it was identified by Dr. James B. Herrick in 1912.

In the next hundred years, traditional fats were replaced by industrial fats. The 1931 Searchlight Recipe Book reflects the transition in American cooking. This, too, contained recipes with butter and cream, but it also called for vegetable oil and “butter substitute” or margarine. Cooks began to change their recipes, no doubt gradually at first. According to the lipids expert Mary Enig, from 1910 to 1970, butter consumption plummeted from eighteen pounds per person per year to four. During the same period, the percentage of vegetable oils in the diet—including margarine, shortening, and refined oils—shot up 400 percent.

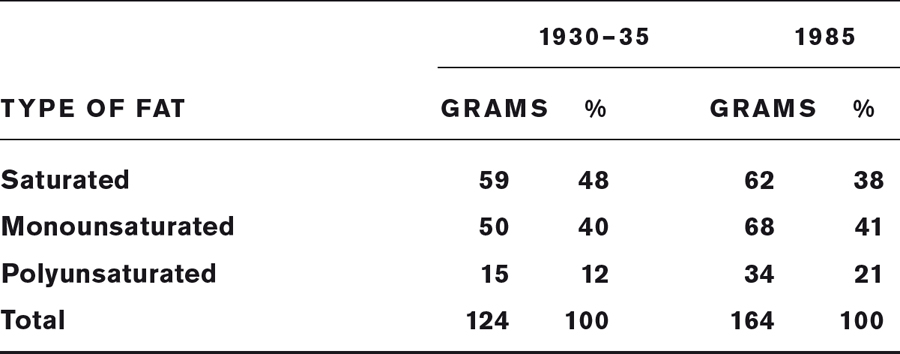

As the following table shows, from 1935 to 1985, the percentage of saturated fats in the American diet fell, while consumption of polyunsaturated vegetable oils more than doubled. (Note, too, that we ate more total fat in 1985, possibly due to larger portions. Not only did the low-fat campaign fail to reduce obesity and heart disease; it simply failed.) The changing face of the most popular fats in the diet tells the same story in a different way. In 1890, the main fats we ate were the traditional farm fats: butter, lard, and chicken and beef fat. One hundred years later, the top three fats were polyunsaturated vegetable oils such as soybean and canola oil, rarely found in traditional human diets.

DAILY FAT INTAKE BY TYPE OF FAT, 1930-85

The most dramatic change in the American diet is the increase in polyunsaturated fats, up by 127 percent. The percentage of saturated fats fell. Many of the polyunsaturated fats shown are hydrogenated vegetable oils, which raise ldl and reduce hdl.

FATS IN THE U.S. FOOD SUPPLY ( IN DESCENDING ORDER OF MARKET SHARE)

Note that all the nineteenth-century fats are unrefined with a long history in the human diet. The top three oils in 1990 were unknown in traditional diets.

|

1890 |

1990 |

|

Lard |

Soybean oil (70 percent hydrogenated) |

|

Beef fat |

Canola oil (often hydrogenated) |

|

Chicken fat |

Cottonseed oil |

|

Butter |

Peanut oil |

|

Olive oil |

Corn oil |

|

Palm oil |

Palm oil |

|

Coconut oil |

Coconut oil |

SOURCE: Mary Enig, Know Your Fats.

With this record of fat consumption—fewer saturated fats, more polyunsaturated vegetable oils—proponents of the cholesterol theory would not have predicted this: by the 1950s, heart disease was the leading cause of death in the United States. It’s a striking fact, worth restating in another way: as consumption of saturated fats fell in the first half of the twentieth century, heart disease rose. This suggests that something other than butter and other traditional saturated fats is to blame for unhealthy cholesterol and heart disease.

That something is the trans fat in hydrogenated vegetable oils like margarine. As the world now knows, trans fats lower HDL and raise LDL, among other things. Real dairy foods, it appears, are innocent. Back in 1991—when heart doctors were touting vegetable oil spreads—Nutrition Week reported that men eating butter ran half the risk of developing heart disease of those eating margarine.13

Recent studies cast doubt on the link between dairy foods, high cholesterol, and heart disease. Consider the Finns, who have the highest cholesterol in the world. “According to the [cholesterol theory], this is due to high-fat Finnish food,” writes Dr. Uffe Ravnskov, author of The Cholesterol Myths and a leading researcher in a group known as Cholesterol Skeptics. “The answer is not that simple.” Within Finland, cholesterol levels vary greatly. In one study, Finns who ate twice as much margarine and half as much butter as other Finns had the highest cholesterol. Those with the highest cholesterol also preferred skim milk to whole milk.14

WHY I DON’T DRINK SKIM MILK

Let me count the ways. The first reason I don’t drink skim milk is flavor—it’s in the fat. Second, butterfat helps the body digest the protein, and bones require saturated fats in particular to lay down calcium. Third, the cream contains the vital fat-soluble vitamins A and D. Without vitamin D, less than 10 percent of dietary calcium is absorbed.15 In the American diet, whole milk was the traditional source of vitamins A and D and calcium. Skim milk—especially industrial skim—is an inferior source of both. Skim and 2 percent milk must, by law, be fortified with synthetic vitamin A and synthetic vitamin D3. Most skim milk is not fresh; it’s made of milk powder reconstituted with water. Finally, whole milk contains glycosphingolipids, fats that protect against gastrointestinal infection. Children who drink skim milk have diarrhea at rates three to five times higher than children who drink whole milk.16

In 2005, researchers reported on a twenty-year study of Welsh men. The high milk drinkers had a lower risk of heart disease than those who drank the least, even though cholesterol and blood pressure were similar in high and low milk drinkers. “The present perception of milk as harmful in increasing cardiovascular risk should be challenged,” wrote the authors, “and every effort should be made to restore [milk] to its rightful place in a healthy diet.”17

As researchers demonstrate every day, many other factors—sugar, lack of B vitamins, too many refined vegetable oils, lack of exercise, smoking—are at work in heart disease. But these anomalies about milk and butter—facts that don’t fit the orthodox theory—cry out for explanation.

Meanwhile, I should mention that some studies have linked milk consumption and high cholesterol. What could account for that? According to Dr. Kilmer McCully, a student of cholesterol metabolism and the author of The Heart Revolution, industrial powdered milk is one culprit. Dried milk powder is created by a process called spray-drying, which creates oxidized or damaged cholesterol. Researchers in 1991 wrote, “Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is more atherogenic than native [unoxidized] LDL.”18 In other words, oxidized LDL causes atherosclerosis.

Milk powder containing oxidized cholesterol is a common ingredient in industrial processed foods including skim milk, yogurt, low-fat cheese, cheese substitutes, infant formula, baked goods, cocoa mixes, and candy bars. Nonfat dried milk is also added to industrial skim and 2 percent milk. In fact, skim milk may be made entirely of dried milk powder mixed with water. Unfortunately, the label is misleading. It will simply say “skim milk,” not “skim milk powder.” The better dairies don’t use powdered milk; they make skim milk from whole fresh milk simply by skimming off the cream.

My conclusion that traditional milk is a good thing is not original. In the 1930s and ’40s, Dr. Francis Pottenger ran tuberculosis clinics where he treated patients with raw milk from grass-fed cows. A professor at the University of Southern California and president of the American Academy of Applied Nutrition, he published dozens of peer-reviewed articles and founded a hospital for the treatment of asthma. In his day, experts were already blaming milk for high cholesterol, but Pottenger believed traditional milk was falsely accused. In his now classic studies on raw and pasteurized milk, Pottenger’s Cats, the doctor wrote: “The charge that milk produces high cholesterol in humans is largely based on the premise that the ingestion of cholesterol and the deposit of cholesterol are the same. Extensive use of quality raw milk, cream, and farm eggs with tuberculosis patients failed to produce a single case of hypercholesterolemia [high blood cholesterol] and atheroma [plaque]. A life-time consumption of clean, fresh raw milk from healthy cattle does not produce metabolic diseases. Cholesterol is not the villain; the villain is what man does to his cattle and milk.”

I like the way Pottenger put that. As I sorted through the facts about milk and health, it was helpful to keep asking: which milk? Many things aren’t what they used to be, and milk is one of them.

TRADITIONAL AND INDUSTRIAL MILK

One of my children’s favorite books is Maj Lindman’s Snipp, Snapp, Snurr, and the Buttered Bread, about Swedish triplets who are hungry for bread and butter. Alas, there is no butter. They go to the family cow, Blossom, who “stood munching her dry hay and looking very sad.” When the boys ask nicely for milk with “plenty of cream” so their mother can make butter, Blossom shakes her head sadly; she has none to give. “I know what she needs,” says one boy. “Fresh green grass.” When spring comes and the pasture turns “green and juicy,” they give Blossom a basket of fresh grass. Delighted, she gives back rich cream, and the equally delighted boys have butter for their bread.

First published in the United States in 1934, The Buttered Bread is a sweet story, but it’s more than that. It nicely illustrates the point—once well known to farmers in Sweden, Ireland, America, and all over the world—that cows produce the most cream and the best butter when eating lush green pasture, particularly the fast-growing grass of spring and fall. In the Swiss dairy villages Weston Price visited, spring butter was so highly prized it was blessed by priests and used in religious ceremonies. Spring butter from grass-fed cows has been tested in the lab (by Price and others) and found to be superior. Blossom’s story is poignant because so few cows today eat fresh grass.

Modern industrial milk and the milk we drank ten thousand years ago—even the milk most Americans (including my Great-Aunt Esther in Milford, Illinois) drank fifty years ago—are different. Traditional milk comes from cows fed mostly on fresh grass and hay; it is raw and unhomogenized. Industrial milk comes from cows raised indoors and fed mostly on a corn, grain, and soybean ration, typically with a dose of synthetic hormones to boost milk production. Industrial milk is then pasteurized and homogenized. Real milk is healthier than the industrial kind, and its superior flavor is unmistakable.

Because cows eat grass, traditional milk is seasonal. Ancient shepherds moved animals frequently to fresh pasture for the best grazing. In the winter, the traditional cow was “dry”—pregnant and not producing milk—and in the spring she gave birth to a calf and began giving milk again. Traditional dairy foods naturally reflect this seasonal pattern. In the spring, when fresh pasture for grazing was plentiful, early shepherds had fresh milk, yogurt, and young cheeses. In the winter, when the cows were dry, they ate aged cheeses made the previous summer and fall. The best dairy farmers still raise cows, goats, and sheep on grass—they are known as grass farmers—and the better cheese shops offer seasonal cheeses made from the milk of grass-fed animals.

Compared to industrial milk, dairy foods from grass-fed cows contain more omega-3 fats, more vitamin A, and more beta-carotene and other antioxidants. Butter and cream from grass-fed cows are a rare source of the unique and beneficial fat CLA. According to the Journal of Dairy Science, the CLA in grass-fed butterfat is 500 percent greater than the butterfat of cows eating a typical dairy ration, which usually contains grain, corn silage, and soybeans.19 Organic milk contains more CLA than conventional milk.

A polyunsaturated omega-6 fat, CLA prevents heart disease (probably by reducing atherosclerosis), fights cancer, and builds lean muscle. CLA aids weight loss in several ways: by decreasing the amount of fat stored after eating, increasing the rate at which fat cells are broken down, and reducing the number of fat cells. Most studies of CLA and cancer have been conducted on animals, and more research is needed, but findings are encouraging. CLA inhibits growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro. A Finnish team found that women eating dairy from pastured animals had a lower risk of breast cancer than those eating industrial dairy.20

The dairy industry is well aware of the commercial opportunity presented by the words cancer fighting or aids weight loss on milk cartons, and scientists are working on ways to increase CLA in milk without going to the trouble of putting cows on grass. In 2003, the Journal of Dairy Science reported that feeding fish oil and sunflower seeds (containing linoleic acid, which cows convert to CLA) raises CLA in milk. There are CLA-fortified milk products in the works, but problems with taste and texture linger. “The addition of CLA to milk decreased overall acceptability, overall flavor, and freshness perception of milk,” one study reported coolly.21 If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, these “functional foods” or “nutraceuticals,” as the industry calls them, pay a high compliment to traditional foods.

Traditional milk is free of synthetic growth hormones. Most industrial milk comes from cows treated with a genetically engineered bovine growth hormone called rBGH (or rBST) to boost milk production. Industrial cows are milked three times a day. Unfortunately for the cow, the hyperproduction stimulated by rBGH increases her risk of mastitis (udder infections) and dramatically shortens her life, from about ten years to five.

Milk from cows treated with rBGH contains higher levels of IGF-1, a naturally occurring growth hormone that is identical in cows and humans. When you drink a glass of milk from a cow treated with rBGH, you get a dose of IGF-1, one of the most powerful of many insulin-like hormones that prompt cells to grow and proliferate. IGF-1 is linked to cancers of the reproductive system, including breast cancer. Because the FDA regards rBGH as safe for human consumption, it does not permit dairy farmers to print “hormone-free” on milk labels, but most dairy farmers who don’t use hormones find a way to say so. If the label is silent, it’s a safe bet the cows were treated with rBGH.

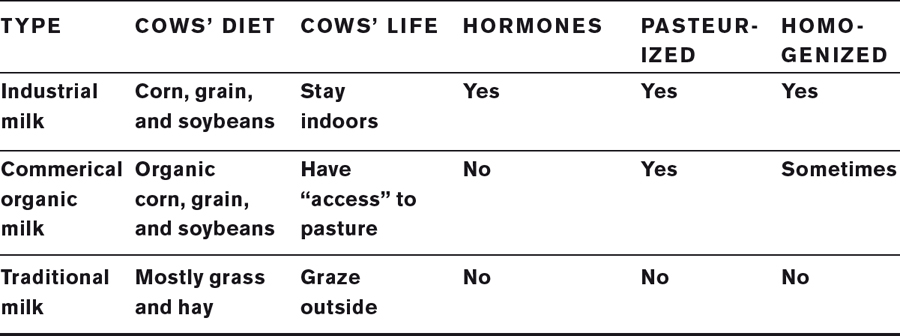

What kind of milk should you buy? Traditional milk is ideal and organic milk second-best. Both are better than industrial milk. Unfortunately, most commercial organic milk comes from cows fed grain, not fresh grass. (All cows must eat some hay for roughage.) Organic cows must have “access” to pasture, but on many large organic dairies, cows spend very little time outside. Grass-fed milk is best, even if it’s not organic. Most grass farmers feed cows on grass and hay with a small grain supplement at milking, as I fed Mabel. That’s acceptable, because even an ancient wild cow would have eaten some grain from seed heads.

INDUSTRIAL, COMMERCIAL ORGANIC, AND TRADITIONAL MILK

The best choice is traditional milk, but it’s not easy to find. Farmers who supply two organic brands, Organic Valley and Natural by Nature, raise cows on pasture. By law, no milk includes antibiotics. If a cow needs antibiotics, her milk is discarded until the drugs have cleared her system.

Modern pasteurization takes three main forms: batch or low-temperature, High Temperature Short Time (HTST), and ultra-high temperature (UHT). The batch method heats a vat of milk to the lowest temperature (145 degrees Fahrenheit) for about thirty minutes. According to Mary and Tim Tonjes, dairy farmers in Callicoon, New York, the batch method is very gentle, allowing plenty of good bacteria to survive, which are critical for good yogurt and cheese. Lately, other small dairies have turned to a high-temperature machine called LiLi, invented in 2006 by Steven Judge, a Vermont dairy farmer who was keen to help other small dairy folk thrive. His method heats the milk rapidly to 162 degrees Fahrenheit, via tubes and steel plates, for just fifteen seconds. Rose Hubbert was the first in New York State to use the LiLi. Happily, Tonjes Farm Dairy and Mother Hubbert sell milk at my local Greenmarket at Union Square. The milks are always fresh and sweet, and I’ve concluded that both pasteurization methods are the next best thing to raw.

Like dairy farmers and milk drinkers, cheese makers care about how milk is treated. The two main effects of cooking milk—it degrades proteins and caramelizes sugars—adversely affect the flavor and texture of cheese. According to The Cheese Reporter, the high-temperature, short-time method, despite its nominally higher temperature of 162 degrees Fahrenheit, has less detrimental effects on the milk than the batch system. This relatively gentle approach looks good for yogurt and butter as well as cheese.

Most milk, however, is treated harshly. UHT milk is subject to high heat (284 Fahrenheit) and pressure for several seconds. UHT milk has a noticeable cooked flavor. The heat also damages the whey proteins that contribute to the creaminess. To compensate, congealing agents like guar gum and carrageenan are added to ultra-pasteurized milk to mimic its natural viscosity. UHT treatment has two main advantages: it kills most pathogens stone-dead (undoubtedly a plus when the milk of thousands of cows from confinement dairies is sloshing about the tankers on the highways) and results in a carton of milk with a long shelf life. When packed in aseptic cartons, UHT milk lasts for six months without refrigeration, and for more than a week once opened. But no decent cheese maker would use UHT milk. As a food, it’s inert, and that’s no good for texture and complexity in cheese.

Pasteurization is generally regarded as a sign of progress, a boon for public health—and there is much truth in that. Pasteurization destroys certain pathogens, including Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli, and Campylobacter. However, pasteurization also affects nutrition, texture, and flavor. It reduces vitamins (B1, B12, C), calcium, phosphorus, useful enzymes, and beneficial bacteria.

It’s worth taking a quick tour of the history of treated milk. The push for pasteurization in the United States began in the late 1800s and the early 1900s. It was a response to an acute and growing public health crisis, in which infectious diseases like tuberculosis were spread by poor-quality milk. Previously, milk came to the kitchen in buckets from the family cow or in glass jars from a local dairy, but soon, urban dairies sprang up to supply the growing populations in or near cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati.

Owners put the dairies next to whiskey distilleries to feed the confined cows a cheap diet of spent mash called distillery slop. For distribution, the whiskey dairies were efficient: in 1852, three quarters of the milk drunk by the seven hundred thousand residents of New York City came from distillery dairies. The last one in New York City (in Brooklyn) closed in 1930.

The quality of “slop milk,” as it was known, was so poor it could not even be made into butter or cheese. Some unscrupulous distillery dairy owners added burned sugar, molasses, chalk, starch, or flour to give body to the thin milk, while others diluted it with water to make more money. Slop milk was inferior because animal nutrition was poor; cows need grass and hay, not warm whiskey mash, which is too acidic for the ruminant belly. Recall from Blossom that cows on fresh grass produce more cream, a measure of milk quality.

Conditions were unhygienic, too. In one contemporary account cited in The Complete Dairy Foods Cookbook, distillery cows “soon become diseased; their gums ulcerate, their teeth drop out, and their breath becomes fetid.” Cartoons of distillery dairies show morose cows with open sores on their flanks standing or lying in muck in cramped stables. Bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis were common, and cow mortality was high. The people milking the cows were often unsanitary and unhealthy, too. Dairy workers could taint milk with human tuberculosis and other diseases.

A public health crisis was brewing. As distillery dairies became common around 1815, contaminated milk caused fatal outbreaks of diseases including infant diarrhea, scarlet fever, typhoid, tuberculosis, and undulant fever (the human version of brucellosis). Infant mortality, often due to diarrhea and tuberculosis, rose sharply, accounting for nearly half of all deaths in New York City in 1839. Reformers blamed the outbreaks of disease on slop milk. The distillery dairies were like the sausage factories later exposed as dirty and unsafe by Upton Sinclair in his 1906 novel The Jungle. Regulation was desperately needed.

Reformers suggested pasteurization to kill pathogens carried in milk. At first, no one suggested that raw milk itself was unsafe, according to Ron Schmid in The Untold Story of Milk—merely that milk should be clean. “Demands for pasteurization allowed for the continued production and sale of clean raw milk,” writes Schmid, a naturopathic physician. “No one was claiming that all milk should be pasteurized, as even the most zealous proponents of pasteurization recognized that carefully produced raw milk from healthy animals was safe.”

This view prevailed, briefly. When a raw milk ban was proposed in New York City in 1907, a coalition of doctors, social workers, and milk distributors defeated it, arguing that safe milk should be guaranteed by inspections, not pasteurization. In 1908, however, a panel of experts appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt concluded that raw milk itself was to blame for food-borne illness. That was the final blow. In 1914, New York required pasteurization of milk for sale in shops. Other states followed suit, and by 1949, pasteurization was the law in most places.

The moral of the tale is clear: the trouble starts when you take a cow away from her natural habitat and healthy diet and force her to become a mere milk machine. By abusing the hapless cow, the distillery dairy owners put human health at risk. Slop milk was responsible for thousands of cases of illness and death—most of them preventable by improving cow health and dairy hygiene. But mandatory inspections were not the expedient solution to the crisis; pasteurization was.

Today, thanks to better animal nutrition, hygiene, and widespread testing, the tuberculosis and brucellosis that ravaged nineteenth-century populations (bovine and human) are rare. Yet even now, when slop milk is long gone, pasteurization plays a vital role in the commercial dairy industry. FDA rules say that “raw dairy products shall not be shipped across state lines for direct human consumption.” Every day, tankers of raw milk rumble down American highways, but the milk is pasteurized before it’s sold to you or me. “For the purpose of current commercial distribution of milk, pasteurization is an undoubted necessity,” writes Grohman, a lively advocate for raw milk, in Keeping a Family Cow. Why?

The typical dairy farmer pours warm milk into a refrigerated tank after milking. Every few days, a truck goes from dairy to dairy collecting raw milk. Thus the milk of thousands of cows is blended before being shipped to the bottling plant or cheese factory. Pasteurization after collection can prevent contaminated milk from one sick cow, unhygienic dairy worker, or dirty nozzle from tainting the clean milk of dozens of other dairies.

Pasteurization also has practical benefits for the dairy industry: it permits more handling, long-distance shipping, and longer storage. Fresh milk doesn’t travel well. Jostling damages its delicate fats and sugars and causes milk to sour. Raw milk lasts a week at most, while HTST pasteurization extends the shelf life of milk to two or three weeks. Ultrapasteurized milk keeps for eight weeks, and UHT milk can last in aseptic packaging months without refrigeration.

In practice, pasteurization can have an unsavory effect on hygiene in the dairy. It allows less scrupulous dairy farmers to be lax with cow health and milk handling because they count on pasteurization to destroy pathogens—at least the heat-sensitive ones—that may taint milk. Many dairy insiders believe that dairy inspections, despite the lessons of slop milk, are still inadequate. I’ve seen some not-very-clean dairies myself.

Nor does pasteurization guarantee protection against food poisoning. Pathogens such as Listeria can survive gentle pasteurization.22 According to the Ohio State University Extension Service, Listeria is slightly more heat-resistant than many other bacteria such as salmonella and E. coli, and will grow at temperatures as high as 140 to 150 degrees Fahrenheit. (Recall that vat pasteurization heats milk to 145 degrees.)

Finally, like any food, both raw and pasteurized milk can carry pathogens. Milk may be contaminated at any point after pasteurization—in handling, transportation, storage, or cheese making—just as easily as before. Indeed, many dairy-related food-poisoning cases are traced to pasteurized milk and cheese.

WHY IS FOOD POISONING ON THE MARCH?

Outbreaks of food-borne illness caused by salmonella and other pathogens have risen steadily since pasteurization became standard. The reasons aren’t well understood, but salmonella and E. coli thrive under the conditions typical in factory farms, including grain feeding, overcrowding, and rapid, mechanized slaughter. Overuse of antibiotics on factory farms has also led to resistance to common antibiotics in strains of salmonella, campylobacter, and E. coli. Whatever the cause, the recent advances of these pathogens cannot be blamed on raw milk. When raw milk was the norm, these threats were less common. (For more on a dangerous form of E. coli that thrives in grain-fed beef cattle, see here.)

Traditional milk differs from industrial milk in one other important way: it is not homogenized. If unhomogenized milk is left to stand overnight, the cream, which is lighter, rises to the top. This is good, because the amount and color of the cream (the yellower, the better) have always been the measure of milk quality, and even today farmers are paid more for more butterfat.

Homogenization forcefully blends the milk and cream, so they never separate. Devised in France around 1900 to emulsify margarine, homogenization pumps milk at high pressure through a fine mesh, reducing its fats to tiny particles. Industrial milk (and even cream) is homogenized during or after pasteurization.

In the United States, homogenization became common soon after pasteurization, largely because it solved two practical problems for the dairy industry. The first was the inconvenient separation of the milk and cream. With pasteurization it was possible to ship milk long distances, but the cream rose in transit, which meant the most valuable part of the milk—the fat—was unevenly distributed from one customer to another. Homogenization spreads the cream throughout the milk, so everyone gets a share. The second problem was cosmetic. After pasteurization, dead white blood cells and bacteria form a sludge that sinks to the bottom of the milk. Homogenization spreads this unsightly mass throughout the milk and makes it disappear.

For many years after its introduction, many Americans declined to buy homogenized milk. “Skeptical consumers were disturbed both by the change in flavor and the absence of the cream line at the top of the bottle,” writes Schmid in his milk history. But dairy companies persisted with a campaign to win the public over, and by the 1950s, most milk was homogenized.

Homogenization is entirely unnecessary. It’s also ruinous for flavor and texture. It breaks up the delicate fats, producing rancid flavors and causing milk to sour more quickly. According to McGee, it takes twice as long to whip homogenized cream, because the fat particles are smaller and more thickly coated with milk protein. I would only add that unhomogenized whipped cream is noticeably more delicious. The best cheeses, too, are made with unhomogenized milk. Happily, unhomogenized milk is perfectly legal, and many smaller dairies sell it, sometimes labeled “cream top” or “cream line.” If you find that whole milk with cream on top is too rich to drink straight, just pour off the cream and put it on apple pie.

THE VIRTUES OF RAW MILK

Bernarr Macfadden was a bodybuilder of the rippling-chest variety you see in old comics. Born in 1868, he was a sickly child but overcame his weak start to become a champion of outdoor activity and fitness. Like many reinvented Americans, he changed his name (choosing a funny spelling) and transformed his body by lifting weights. Macfadden kept fit by walking the twenty-five miles from his house in Nyack to New York City—barefoot. In a long, flamboyant career, he became rich and famous selling exercise equipment and publishing fitness manuals, often using his own splendid physique to illustrate poses akin to Greek statuary. At the age of sixty-five—if pictures don’t lie—Macfadden had the sort of body readers of Men’s Health dream of: a hulking, inverted-pyramid torso atop narrow hips and bulging thighs. Macfadden attributed his fine form to raw milk.

In 1924, Macfadden published The Miracle of Milk: How to Use the Milk Diet Scientifically at Home. Having studied nineteenth-century European milk cures, he began to treat people with grass-fed, whole raw milk. He found it useful for a range of conditions from neuralgia to bronchitis to heart disease, but he was particularly enthusiastic about milk’s ability to help the scrawny build muscle and the flabby lose fat. He gushes about the “plump cheeks,” “firm and shapely breasts,” muscle tone, and symmetry of patients who took his milk cure, which involved drinking two to six quarts of raw milk daily.

Raw milk has modern fans, too. A surprising number of commercial dairy farmers prefer it. According to a 1999 survey in Hoard’s Dairyman, 60 percent of dairy farmers drink raw milk at home. When Schmid, author of The Untold Story of Milk, asked dairy farmers why, they told him, it “tastes good” or “makes me feel better” or “I don’t like store-bought food.” Many dairy farmers tell me the same. Barbara King, who raises Ayrshires in Cayuga County, New York, told me, “Raw milk straight from the bulk tank has the best flavor.” Another dairyman, a former engineer, told me he’s raising ten kids on raw milk. Perhaps they’re onto something.

It’s no secret that raw milk is more nutritious than pasteurized milk. Pasteurization destroys folic acid and vitamins A, B6, and C. In 1941, the U.S. government issued a report stating that “the cows of this country produce as much vitamin C as does the entire citrus crop, but most of it is lost as the result of pasteurization.” Pasteurization inactivates the enzymes required to absorb the nutrients in milk: lipase (to digest fats); lactase (to digest lactose); and phosphatase (to absorb calcium). Phosphatase explains why raw milk contains more available calcium.23 Pasteurization also creates oxidized cholesterol, alters milk proteins, and damages omega-3 fats.

Heat destroys or damages lactic acid bacteria in raw milk—the same beneficial bacteria in yogurt that aid digestion and immunity. When left alone in raw milk, the good bacteria kill off harmful bacteria which may taint milk during handling, according to Madeleine Vedel, an American expert on the traditional raw milk cheeses of Provence. When staphylococcus is introduced to warm pasteurized milk, it proliferates quickly and dangerously, but when added to warm raw milk, it grows much more slowly and may even be eliminated by good bacteria. “By pasteurizing milk we turn it into the ideal medium for dangerous bacteria,” concludes Vedel, who owns the Cuisine et Tradition School of Provençale Cuisine in Arles with her husband, Erick, a French chef.24

My friend Joann, the dairy farmer, keeps her arthritis at bay by drinking a cup of raw milk at each milking. The arthritis cure is due to the anti-inflammatory Wulzen factor, identified by the researcher Rosalind Wulzen in raw cream and butter in the 1941 American Journal of Physiology. The Wulzen factor also prevents calcification of the joints, hardening of the arteries, and cataracts. Raw butter contains myristoleic acid, a monounsaturated fat that fights pancreatic cancer and arthritis.25

THE VIRTUES OF RAW MILK AND CREAM

✵Raw milk contains heat-sensitive folic acid and vitamins A, B6, and C.

✵Raw milk contains important heat-sensitive enzymes: lactase to digest lactose; lipase to digest milk fats; phosphatase to absorb calcium, which, in turn, allows for the digestion of lactose.

✵Raw milk offers beneficial bacteria, including lactic acids, which aid digestion, boost immunity, and eliminate dangerous bacteria.

✵Raw milk contains the antioxidant glutamine and promotes glutathione, the “master” antioxidant.

✵Raw cream contains a cortisonelike agent (the Wulzen factor), which combats arthritis, arteriosclerosis, and cataracts.

✵Raw butter contains myristoleic acid, which fights pancreatic cancer and arthritis.

Dr. Thomas Cowan, a physician in San Francisco, treats many conditions with raw milk, including eczema, diabetes, and arthritis. He is following a long and respectable medical tradition. In the 1920s, the Mayo Foundation, forerunner of the prestigious Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minnesota, prescribed an all-milk diet known as “the Milk Cure.” In a 1929 article, “Raw Milk Cures Many Diseases,” a Mayo doctor described milk as an easily digestible food, rich in enzymes, vitamins, and minerals, with a perfect balance of protein, fat, and carbohydrate. Like Macfadden, the bodybuilder, the Mayo doctors found raw milk effective for weight loss and for many ailments, including poor digestion, inflammation, rheumatism, asthma, skin conditions, bronchitis, high blood pressure, kidney disease, and even heart disease.26

Today, in the age of pasteurization, old literature on the benefits of raw milk makes interesting reading. In 1916 and 1917, the American Journal of Diseases of Children reported that raw milk prevents scurvy in babies, probably because heat destroys vitamin C. In 1933, the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin reported that raw milk promotes growth and calcium absorption. In 1937, the Lancet said that children on raw milk had greater resistance to tooth decay and tuberculosis. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry reported in 1938 that certain pathogens do not grow in raw milk but proliferate in pasteurized milk. The good bacteria in raw milk—dubbed natural antiseptics by the authors—killed the dangerous ones. Sadly, this science is neglected today.

THE MILK DIET: A MODERN EXPLANATION

Recent studies show that people who consume more milk, yogurt, and cheese lose fat (especially belly fat) and gain lean muscle. It’s not clear why. The CLA and omega-3 fats from the milk of grass-fed cows prevent obesity and build lean muscle, but it’s likely the subjects in these studies ate industrial dairy foods. In The Calcium Key, Professor Michael Zemel, director of the Nutrition Institute at the University of Tennessee, argues that calcium is the secret. Zemel explains how low calcium elevates the hormone calcitriol, which causes the body to hoard calcium and send it to fat cells, where it signals cells to store fat. A calcium-rich diet lowers calcitriol and stimulates weight loss. Zemel found that calcium from dairy foods is strikingly more effective than calcium from fortified foods or supplements.27 Whole raw milk is the best source of calcium; the body needs the enzyme phosphatase (destroyed by heat) and vitamin D (in the fat) to absorb calcium.