Real Food: What to Eat and Why - Nina Planck (2016)

Chapter 1. I Grow Up on Real Food, Lose My Way, and Come Home Again

FIRST I EXPLAIN WHAT REAL FOOD IS

When I was growing up on a vegetable farm in Loudoun County, Virginia, we ate what I now think of as real food. Just about everything at our table was local, seasonal, and homemade. Eating our own fresh vegetables certainly made me proud; they tasted better than the supermarket vegetables other people ate. But I regarded homemade granola, whole wheat bread, and chicken livers—not to mention the notable lack of store-bought processed foods in brightly colored boxes in our kitchen—as uncool. Today, my embarrassment over the simple American meals we ate is long gone, and I regard the food I grew up on as the very best. It’s true that in certain quarters these days, sautéed chicken livers are fashionable, but I don’t care about that; I prefer real food because it’s delicious and it’s healthy.

What is real food? My rough definition has two parts. First, real foods are old. These are foods we’ve been eating for a long time—in the case of meat, fish, and eggs, for millions of years. Some real foods, such as butter, are more recent. It’s not absolutely clear when regular dairy farming began, but we’ve been eating butterfat for at least ten thousand years, perhaps as many as forty thousand. By contrast, margarine—hydrogenated vegetable oil made solid and dyed yellow to resemble traditional butter—is a modern invention, merely a century old. Margarine is not a real food.

Consider the soybean. Asians have been eating foods made from fermented soybeans, such as miso, tofu, and soy sauce, for about five thousand years. Without fermentation, the soybean isn’t ideal for human consumption. But most of the modern soy products Americans eat are not traditional soy foods. The main ingredient in modern soy foods and many processed foods, such as low-carbohydrate snack bars, is “isolated soy protein,” a by-product of the industrial soybean oil industry. This unfermented, defatted soy protein is not real food.

Second, real foods are traditional. To me, traditional means “the way we used to eat them.” That means different things for different ingredients: fruits and vegetables are best when they’re local and seasonal; grains should be whole; fats and oils unrefined. From the farm to the factory to the kitchen, real food is produced and prepared the old-fashioned way—but not out of mere nostalgia. In each of these examples of real food, the traditional method of farming, processing, preparing, and cooking enhances nutrition and flavor, while the industrial method diminishes both.

*Real beef is raised on grass (not soybeans) and aged properly.

*Real milk is grass-fed, raw, and unhomogenized, with the cream on top.

*Real eggs come from hens that eat grass, grubs, and bugs—not “vegetarian” hens.

*Real lard is never hydrogenated, as industrial lard is.

*Real olive oil is cold-pressed, leaving vitamin E and antioxidants intact.

*Real tofu is made from fermented soybeans, which are more digestible.

*Real bread is made with yeast and allowed to rise, a form of fermentation.

*Real grits are stone-ground from whole corn and soaked with soda before cooking.

Industrial food is the opposite of real food. Real food is old and traditional, while industrial food is recent and synthetic. The impersonation of real food by industrial food, by the way, is neither accidental nor hidden. An industrial food like margarine is intended to be a replica of a traditional food—butter. Real food is fundamentally conservative; it doesn’t change, while industrial food, by contrast, is under great pressure to be novel. The food industry is highly competitive and relentlessly innovative, producing thousands of new food products every year. Most of these “new” foods are merely new combinations of old ingredients dressed in a new shape (individually wrapped cheese slices instead of the traditional wheel of pressed cheese) or new packaging (whipped cream in an aerosol can). Or the new recipe has been tweaked to ride the latest food craze (cholesterol-free cheese, low-carbohydrate bagels). Real food, on the other hand, doesn’t change because it doesn’t have to. My morning yogurt is a masterfully simple recipe for cultured milk, passed down for thousands of years.

So that’s my custom definition of real food: it’s old, and it’s traditional. To lexicographers, sticklers, and nitpickers (you know who you are), it’s no doubt hopelessly imprecise and incomplete, but I hope it’s clear enough for our purposes.

People everywhere love traditional foods. They’re fond of a nice steak, the crispy skin of roast chicken, or mashed potatoes made with plenty of milk and butter. But they’re afraid that eating these things might make them fat—or, worse, give them a heart attack. So they do as they’re told by the experts: they drink skim milk and order egg white omelets. Their favorite foods become a guilty pleasure. I believe the experts are wrong; the real culprits in heart disease are not traditional foods but industrial ones, such as margarine, powdered eggs, refined corn oil, and sugar. Real food is good for you.

Does that mean you should enjoy real bacon and butter not because they’re tasty but because they’re actually healthy? In a word, yes. Some might mock this as a characteristically American case for real food—call it the Virtue Defense. Gina Mallet, an Anglo-American “food explorer” who defends real foods, including beef and raw milk cheese, in Last Chance to Eat: The Fate of Taste in a Fast Food World, calls the modish philosophy healthism—and her intent is not to flatter. As scientists began to blame the diseases of civilization on diet, Mallet writes, “a new philosophy emerged, based on the notion that death could be delayed, perhaps even cheated, if a person monitored every single piece of food she ate.” I’m concerned about nutrition, but I wouldn’t call myself a healthist. For one thing, living forever doesn’t interest me, and for another, flavor does.

Someone else—a French chef perhaps—might take a different approach in defense of real food. Less interested in health, he might champion pleasure for its own sake. Great—I’m all for pleasure. If the sheer sensual joy of eating shirred eggs or homemade ice cream is enough for you to shed your guilt, throw away phony industrial foods, and return to eating real foods, all the better. I’ll leave the nature of taste and satisfaction, guilt and pleasure to the cultural critics and moral philosophers. This book is about why real food is good for you.

WE BECOME VEGETABLE FARMERS

My parents chose to farm, but I didn’t. My father had a doctorate in international relations from Johns Hopkins and taught political science at the State University of New York in Buffalo, where I was born in 1971. A bright young professor, he got tenure early, and he could teach anything he wanted. My mother, for her part, was at home with three young children and very happy. But they always had unconventional plans and utopian ideas: unsatisfied with our local public school in Buffalo, they started and ran a neighborhood school with other parents. They loved physical work and kept a plot in a garden outside of town.

In January 1973, our friends Tony and Mariette Newcomb came to see us in Buffalo. They brought eggs and beef they had raised on their farm in Virginia. “We were knocked out by that,” my father said. That very year, Dad quit teaching and we moved south to Virginia to learn vegetable farming from the Newcombs. Committed to farming before they’d even tried it, they also bought sixty acres of farmland in Loudoun County, Virginia, for seventy-five thousand dollars they cobbled together with loans from friends and family. My sister, Hilary, was ten years old, Charles was six, and I was two. They wanted us to grow up on a farm.

Our first years farming as apprentices to the Newcombs were wonderful and strange, very different from the life of a professor’s family. Mom and Dad worked all the time, and we lived simply. With no kids my age to play with, I was often lonely hanging around the farm or playing at make-believe grocery shopping at our farm stand. In many ways it was a hard life. But however sore and tired they were, they loved farming, and for us kids, the farm was a rusty, dusty, paradise embracing both work and goofing off, and the Newcomb kids were like cousins.

On September 19, 1977, Hilary was struck by a car coming home from her ballet class. She was fourteen years old. We buried her at home, a few days later, in the woods under a dogwood tree, where Tony Newcomb said there would never be any possibility of disruption. My father gathered boards from poplar trees grown on the farm and cut by the local Amish miller and built a coffin; many people picked up the hammer to nail it shut. My mother braided baler twine ropes to support the coffin. I scampered along as shifting teams of bigger people carried it slowly up Grove’s Hill, where everyone started shoveling.

On the same hill in 1984, Hiu Newcomb buried her husband, Tony, who founded Potomac Vegetable Farms with land they bought in the early 1960s. Many years later, Hilary’s best friend Anna Newcomb and her sister Hana helped to preserve the Newcomb family land. In 2000, they built a visionary co-housing community of nineteen houses, which circle the small, rustic cemetery.

When I visit my sister’s grave, I remember how small I felt as a six-year-old, the awful necessity of saying good-bye to my big sister. “I guess Hilary is not going to take me swimming anymore,” I told my parents. But I also remember the family, friends, and community who came to bury her, with their own hands, and I’m comforted that the spirit of community at her funeral is still present in the friends, family, preservationists, and farmers who live near her grave.

But all that came later. Our family, suddenly and cruelly diminished, left Vienna, Virginia, and, worse, we had to leave Hilary there. Soon after the funeral, we packed our things, as previously planned, and moved. We headed south, to Swannanoa, North Carolina, where my father would teach political science and be director of the work program at Warren Wilson College, and my mother found work at the local extension service. Now smitten by the farming life, my parents kept a cow and chickens, and grew an acre of tomatoes. Our time in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains is blurry, but what stands out is sad. Dislocated and grieving, I struggled to make friends. One day I crashed my bike into a glass lobby, breaking my arm and tearing a piece of skin off my ribs. I can still hear the tinkling of broken glass, like the wind chime on a porch, as my bike came to rest and then wobbled over. On a scrap of paper, I wrote a note to my six-year-old self, “I can, I do, I will.” Much later, I made good on that pledge to myself. But in 1978, I couldn’t recover from the terrible gash my sister’s death left on our cozy (if scrappy) farming life at Potomac Vegetable Farms. My parents didn’t have the time, and I lacked the means, to heal.

At the end of this lonely year, we moved to our own place, in the tiny hamlet of Wheatland, Virginia. We arrived at the farm late on Christmas Eve in 1978. All our things, including a few pieces of farm equipment, were tied up in a rickety pile on the back of our green flatbed Ford. There was too much snow to drive up to the house, and there was no driveway anyway, so we parked at the edge of the property and walked a quarter of a mile.

The old tenant house had little charm. The kitchen floor was covered with a dirty mustard carpet. Under that was linoleum; under that, plywood, hiding yellow pine floorboards. The sink drained through the kitchen wall into the backyard. We heated the house and water for baths with wood fires. But my parents are relentlessly cheerful and practical, and over the years we fixed up the house, scrubbing, scraping, and painting, with the simple faith that natural materials, such as wood floors, are beautiful no matter how modest or worn.

In the spring of 1979, we became farmers. While other kids played soccer and went to the beach, Charles and I spent the long humid Virginia summers hoeing, weeding, mulching, picking, and selling vegetables. Some farm chores are part of the past; now we mulch every crop to keep weeds down, so there’s hardly any hoeing, but I spent many dusty hours hoeing rocky pumpkin fields back then. Other lost tasks I think of more fondly. On the mulch run we brought home scratchy hay bales from local farms. You had to be strong to toss them up onto the wagon to the stacker, but later we unrolled little round bales like carpets down tomato aisles. It’s much more civilized but less romantic.

When I was eight years old, I began to sell our vegetables at roadside stands in the towns near our farm. After my parents dropped me off, I would set up the table, umbrella, and signs, and wait for people to buy our tomatoes, zucchini, and sweet corn. Stand duty was often lonely, and sometimes scary for a young girl, especially when it got dark. More to the point, we couldn’t make a living this way—not with sales of $200 here or $157 there. That winter, my parents took part-time jobs—Dad as a handyman, and Mom waiting tables at the Pizza Hut in Leesburg—to make ends meet.

Only one year later, in 1980, the first farmers’ market in our area opened in the courthouse parking lot in Arlington, Virginia, and everything changed. We picked and bunched beets and Swiss chard and drove into town. Scores of grateful customers flocked to our vegetables, as if they had waited all their lives for roadside stands to come to the suburbs of Washington, D.C. That summer we took our vegetables to three weekly farmers’ markets, and soon we abandoned roadside stands altogether. With farmers’ markets, we began to make a modest profit and farming became a lot more fun. Right up to the day they retired, my parents made a living exclusively from selling at farmers’ markets. They sold twenty-eight varieties of tomatoes, a dozen different cucumbers, garlic, lettuce, and many other vegetables at more than a dozen markets a week in peak season.

We never liked the term back to the landers for people who gave up city jobs for farm life. How can you go back to a place you’ve never been? Yet that’s what people called us. I always thought of us as farmers, because farm life was all I ever knew. I have no memories of being a professor’s daughter with a stay-at-home mother, only of my parents coming in wet from the morning corn pick in the very early days farming with the Newcombs. Even now, after living in Washington, Brussels, London, and now New York City, I still think of myself as a farm girl, happiest when I’m around tomatoes and bugs and creeks.

I AM FORCED TO EAT HOMEMADE FOOD

My mother was a natural, if amateur, scientist with an interest in biology, nutrition, and babies. She read about the pioneering experiments of Clara Davis in the 1920s and ’30s. Davis set out healthy, whole foods for infants and let them eat anything they wanted for months at a time. The smorgasbord included beef, bone marrow, sweetbreads, fish, pineapple, bananas, spinach, peas, milk and yogurt, cornmeal, oatmeal, rye crackers, and sea salt. At any given meal, the choices babies made could be extreme: one baby ate mostly bone marrow; others loved bananas or milk. One occasionally grabbed handfuls of salt. Over time, however, the babies chose a balanced diet, rich in all the essential nutrients, surpassing the nutritional requirements of the day, and they were in excellent health. The nine-month-old boy with rickets drank cod-liver oil (rich in vitamin D) until his rickets was cured; then he ignored it.

The Clara Davis experiments were limited, and to my knowledge, never repeated. Proven or not, the idea made a deep impression on my mother. She believed that anyone, even an uninformed baby or child—perhaps especially a baby or child—could feed himself properly on instinct alone if you gave him only healthy foods, and that was how we ate—at home anyway. There was some leeway for junk food on car trips (Oreos were a treat), and on the rare occasions when we ate out, we could order anything we wanted. At home, however, there was only real food, and my parents never told us what to eat or how much or when.

My mother’s other nutritional hero was Adelle Davis, the best-selling writer who recommended whole foods and lots of protein. Before dinner, Mom put out carrot, apple, or turnip sticks so we would eat raw fruits and vegetables when we were hungry for a snack. Main dishes were basic American fare: fried chicken, tuna salad, spaghetti, quiche, meatloaf, potato pancakes with homemade applesauce. There were many frugal dishes, such as chicken hearts with onions, and we ate a lot of rice and beans. At dinner we always ate vegetables and a large green salad.

Most of our food was local and seasonal, which is no doubt why I fondly remember the exceptions, such as the boxes of oranges and grapefruit we bought each winter. We drank fresh raw milk from our Jersey, ate bright-orange eggs from our free-ranging chickens, and a couple of times we slaughtered spent laying hens for soup. Our honey came from a local beekeeper. Occasionally, there was venison or bluefish when we let local people hunt or fish on the property. In those days, few farmers nearby were raising meat and poultry for local markets, so we had to buy those foods at the store, but today the beef, bison, lamb, and chicken usually come from farmers we know.

Above all, we grew truckloads of vegetables. The simple act of picking vegetables for dinner—a pleasure known to all kitchen gardeners, one that feels maternal and generous to me—is positively extravagant on a real farm, where there are acres of fresh things to choose from. Visiting my parents at their farming peak in June, I would set out from the kitchen with a basket and a rough plan of attack—to find lettuce, zucchini, and young fennel—and come back with a wheelbarrow-full, seduced along the way by the old spinach patch (abandoned in the hot weather) or by a head of green garlic, still too young to sell but irresistible. If I were feeling lazy, there’d be no need to go to the fields at all. In the cool, dark basement, beans, eggplant, and peppers sat in baskets, ready for market.

Our berries, lettuce, herbs, and vegetables made a feast of every meal from April to November. In the old, strict days when every penny counted, the first picking, however tiny—a dozen spears of asparagus or two pints of raspberries—went to market, not to the kitchen. But once each crop was in full swing, we ate as much as we wanted. We grew only the best-tasting varieties, such as Earliglow strawberries and Ambrosia melons. What we didn’t grow, we bought or bartered for at farmers’ markets. In the winter, we ate our own canned tomatoes and frozen red bell peppers and my mother bought large volumes of produce from our local supermarkets. We all ate huge amounts of vegetables—four ears each of buttered corn, giant plates of sliced tomatoes, enormous green salads—and still do. I’ve never met anyone who eats more vegetables than my family. To me, a half-cup serving of cooked broccoli is silly, a doll’s portion.

Much of what we ate was homemade. We made whole wheat bread and buckwheat pancakes from fresh flour ground in an electric mill, and apple, beet, and carrot juice in the juicer. Making granola was a weekly chore for us kids. On winter car trips we packed our own food, typically large pots of beans and rice, bread, apples, and peanut butter. The everyday dessert was apple salad with yogurt or mayonnaise, walnuts, coconut, and honey. When we had proper desserts such as vanilla pudding, cherry pie, and strawberry shortcake—which was not often—they were always made from scratch. Portions were big, leftovers prized, and nothing was wasted. Eggshells and vegetable scraps went in a bucket for the chickens.

It all sounds perfect now, but jars filled with blackstrap molasses and homemade granola did not impress me. I wanted American food, the kind normal kids ate. By far the biggest taboo in our house was junk food, and for that very reason it was deeply compelling. When I had stand duty in the town of Purcellville, I made a beeline for the High’s convenience store to buy ice cream sandwiches—and told no one. On my eleventh birthday, my parents said I could have anything I wanted for dinner, and I greedily ordered a store-bought cake. I can still taste the faintly metallic neon frosting. Yet I ate it gamely, unwilling to admit that my hideous cake was inferior to the dessert my mother always made on our birthdays: chocolate éclairs with real milk, butter, and eggs, and good chocolate. The first time I laid eyes on an all-you-can-eat salad bar, at the Leesburg Pizza Hut where my mother waited tables that first winter, I ate a bowl of tasty-looking bacon bits with a spoon. They made me very sick—and embarrassed, too. No one told me you don’t eat bacon bits—the lowest form of pork, if they aren’t imitation bacon made of soy protein—straight.

These wince-inducing memories suggest that the Clara Davis experiments—sometimes referred to as proving “nutritional wisdom”—work only when all of the choices are good ones. Sure, the baby cured his rickets with cod-liver oil, like a little instinctive scientist, or a wild animal self-medicating by eating certain plants. But Davis gave the babies only good foods to eat. What if the babies could have eaten ice cream sandwiches, neon pink cake frosting, and bacon bits? To my knowledge, no one has tried such an experiment—unless you count our daily exposure to all manner of cheap junk food—but the evidence is not encouraging.

In the short term, at least, availability seems to determine what we eat, rather than instinct for health. Squirrels, given the choice between acorns and chocolate cookies, take the cookies. The natural diet of sheep is grass, but when offered dense carbohydrates—the ovine equivalent of store-bought cake—they will binge until they are listless. Even a modern hunter-gatherer will drink honey until his teeth rot, if he can get enough.

“As stupid as these choices seem, one can’t really blame them on a lack of nutritional wisdom,” writes Susan Allport in The Primal Feast. “During the course of evolution, squirrels, sheep, and humans have rarely encountered large quantities of concentrated, high-energy foods. Why should the food selection mechanisms of animals include protections against overeating these things? Our human tastes for foods evolved and enabled us to survive in the forests and the African savannas where animals were lean and fibrous, food shortages were a fact of life, and sugar came only in the form of ripe fruits and honey, foods that were available only on an intermittent, seasonal basis.” It seems that animals and humans both lack brakes for runaway junk-food craving.

Once you grow up, of course, you have to take responsibility for what you eat, and my parents believed in Emersonian self-reliance. When I was ten or so, they decided that Charles and I should learn to cook, and we drew up a dinner and dishes schedule. We all cooked the same way, building simple meals around our abundant, gorgeous vegetables. The ingredients weren’t fancy, and the recipes weren’t sophisticated. I loved my night to cook, especially the grown-up feeling of providing for my family, and here and there I made a stab at something original. Once I prepared Chinese noodle soup by boiling vegetables and pasta in water with lots of soy sauce. My mother wasn’t impressed—it probably tasted terrible—but I was proud of my creation and the memory of her reaction hits a tender spot. Another time I baked chicken with rosemary. “It’s good,” said Charles, “except for the pine needles.” My cheeks flushed with shame for introducing a fancy—and risible—ingredient to plain old chicken. Simplicity was a virtue, and culinary experiments weren’t much encouraged.

What was prized was the idea of the farm as physical paradise. We were encouraged to sigh with delight over the sound of the spring peepers, the flash of the fireflies, the scent of honeysuckle, and—most of all—the flavor of our own melons and tomatoes. I was already a nature lover and took huge pleasure in our beautiful farm and unsurpassed vegetables. But I never understood how appreciation of nature conflicted with making dinner a bit different—tastier, fancier, sexier. Wasn’t nice food also a gift of nature?

Now it’s obvious that I lived in a kind of paradise about food. My mother’s philosophy—provide good homemade food on a budget and then leave your kids alone to eat what they like—was working. Charles and I were healthy, physically active, never picky eaters like other kids we knew. As for me, it all seemed simple. We grew the best vegetables in the world. At home there was only good stuff, which I ate happily. From time to time, there were treats—like Danish butter cookies—or compelling, but quite possibly regrettable, stuff in restaurants. Mostly, I was ignorant about the big world of food and therefore unashamed. When the school principal sent me home with a free turkey for Christmas, it seemed like nothing more than a stroke of good luck. If my parents didn’t care that we didn’t have a lot of money and ate simple food, why should I? Above all, I wasn’t neurotic about food or my body or my appetites. An untroubled child with lots of energy, I ate what I wanted, when I was hungry for it. Naturally, it didn’t last.

MY VIRTUOUS DIET MAKES ME PLUMP AND GRUMPY

A typical teenage girl, I was anxious about all sorts of things, and placed my anxiety squarely on—what else?—food. The experts said that many of the foods I grew up on—like Yorkshire pudding topped with a pool of hot butter—were unhealthy. The smart advice was to be a little bit more vegetarian: eat less meat, less dairy, less saturated fat.

The medical wisdom began to dovetail with our somewhat alternative subculture. Our farming friends and the college students who worked on our farm each summer were health-conscious and green. In those circles, being a vegetarian—better yet, a vegan—was environmentally, nutritionally, and ethically correct. In the worker kitchen down by the little pond, the famous vegetarian Moosewood Cookbook was the bible, and communion was rice and beans. Times have changed. Now the workers buy raw milk, eat local venison, and dream of keeping chickens, goats, and cows on their own farms.

The ecological and political arguments for a vegetarian diet came to the fore in 1971, the year I was born. In her seminal book, Diet for a Small Planet, Frances Moore Lappé argued that modern beef farming was ecologically unsound (it wrecks natural habitats), politically unjust (you could feed more people on the grain cattle ate than on the steaks), and nutritionally unnecessary (we don’t need all that protein). The idea that a vegetarian diet was healthier clinched it for me, and I became a vegan in high school. It was perhaps my only act of rebellion against my stubbornly tolerant parents. My state of mind is still vivid. With all the bad press animal foods were getting, the quickest route to salvation seemed clear: eat only plants.

The summer of 1989 was the last season I lived and worked on the farm. In late August, still the height of the season, my parents drove me to Oberlin College, with the stereo shelf my mother built and my other things in the back of a pickup. Later I transferred to Georgetown University and set up house with my boyfriend in Washington, D.C. In my own kitchen, I was free to invent my own philosophy about food. But I’d lost my instincts and didn’t trust my appetite. Eating became an intellectual question. How many people could you feed on the grain it took to raise one steak? If saturated fats are dangerous, why eat any? The vegan experiment ended fairly quickly—I liked yogurt—but for many years I was a vegetarian.

Fear of fat and cholesterol dominated our little kitchen in the row house on Twenty-seventh Street in northwest Washington. Even a hint of slippery, creamy food on the tongue sent me into panicky disapproval. Peering at labels, I stocked the pantry with low-fat foods. In those days, I believed the conventional nutritional wisdom: that unsaturated fats were good for cholesterol and saturated fats were not. Monounsaturated olive oil—the star of the vaunted Mediterranean diet—was the only fat I trusted … but not much of it. The taboo on cholesterol and saturated fats meant no beef, eggs, cream, chocolate, or coconut. Our only dairy was nonfat yogurt, and there was plenty of rice milk and soy ice cream.

Today it’s hard to picture what we ate. I loved to cook, but most foods were off the menu—no beef, pork, lamb, chicken, fish, milk, or eggs. We ate lots of fresh local vegetables, large green salads, burritos, and bean soups. I ate mountains of rice, beans, and pasta. For dessert there was fruit salad, but without the mayonnaise of my youth. A well-used recipe for nonfat oatmeal bars with pineapple springs to mind, and on special occasions I made fruit pies with butter crust. Now and then I grated low-fat cheese over salad or treated us to grilled shrimp from the waterfront fishmonger.

Now it’s clear why my boyfriend gave me a cookbook on my nineteenth birthday: the poor fellow was desperate for variety. It was Martha Stewart’s Quick Cook Menus, and I read it from cover to cover in one sitting, fascinated with the fancy foods she touted, like balsamic vinegar, crème fraîche, and homemade mayonnaise. Now Martha Stewart is famous for all the domestic arts, from antique paints to pinecone crafts, but in those days she was a champion of simple, seasonal meals—and her recipes always worked. Quick Cook was my first cookbook, it bears the marks of many good meals, and I still use it.

MY VIRTUOUS DIETS

At the height of my various nutritionally correct diets (vegan, vegetarian, low fat, low saturated fat, and low cholesterol), this was the picture:

REAL FOODS OFF THE MENU

✵Beef, lamb, game, poultry, fish, and shellfish

✵Milk, cream, butter, cheese, and eggs

✵Chocolate and coconut

REAL (BUT RICH) FOODS STRICTLY LIMITED

✵Olive oil

✵Avocados

✵Nuts

REAL FOODS I ATE PLENTY OF

✵Fruits and vegetables

✵Brown rice and beans

✵Whole wheat bread

NEW FOODS I TRIED TO LOVE

✵Various imitation foods made with soy and rice

FAT-FREE, SWEET THINGS I ATE QUITE A LOT OF

✵Juice

✵Nonfat frozen yogurt

As for my health, I felt terrible. My digestion was poor, and I was moody, tearful, and tender in all the wrong places before I got my period. In cold and flu season, I got both. I was depressed, too. Partly to stave off the gloom, I ran three to six miles a day, six days a week. On this virtuous regime I also gained weight steadily—and before I knew it, I was plump. How plump? Well, women and weight is a treacherous topic; no one agrees on the definitions and people get touchy, so I’ll try to be objective. I’m almost five feet five inches tall and for the last fifteen years I’ve weighed 119 to 125 pounds, much of it muscle. In my vegetarian days, I was 147 pounds and soft all over. That’s a body mass index (BMI) of almost 25, squarely in the “overweight” category.1

Back home on the farm in Wheatland, meanwhile, my omnivorous parents were the healthiest people I knew, lean and cheerful as they tucked into fried eggs and pork chops. Something was wrong with me, but I certainly didn’t suspect my perfect diet. In 1995, in this none-too-healthy, somewhat muddled state, I moved to Brussels to work for NATO’s parliamentary arm. I was twenty-three going on twenty-four, it was my first time going to Europe, and I was full of anxiety. My friend Indya had to reassure me, “There are vegetarians in Europe.”

I AM RESCUED BY FARMERS’ MARKETS

On July 4, 1996, after a year in Brussels, I moved to England as a journalist for Time magazine and found a place on St. Paul Street in Islington, a groovy north London neighborhood. A typical London row house, it had a little, overgrown garden, which I cleared out, hauling away many buckets of shattered concrete from an old patio. A farmer from Cambridgeshire delivered a load of well-rotted compost, which I had fun digging under. I laid a stone path to a spot where the morning sun fell, and put a bench there. One other place got sun, and there I built a raised bed, barely four feet square, for zucchini, herbs, and lettuce. It was a tiny patch, nothing like sixty acres in Virginia, but it was mine.

Apart from the clouds, I loved everything about England and made lots of friends, but soon I was homesick—not for Virginia but for local produce. My sunny patch was too small for all the vegetables I wanted to grow. I tried several whole foods shops and what they call “box schemes” (a weekly delivery), but they all disappointed. The produce was organic, but it was often wilted, bland—and imported. I took the Tube to London’s famous street markets, which, not long ago, featured local produce from Kent (“the Garden of England”), but they mostly sold Dutch peppers and Israeli tomatoes and T-shirts.

Imported fruits and vegetables couldn’t compare to the ones we grew at home. I longed for ripe strawberries in season, fresh asparagus with its scales unfolding, and traditional apples instead of the standard commercial fare: underripe Granny Smiths from Australia or insipid Red Delicious from Washington State. Desperate for good produce, I rented a site near my house, set about finding farmers, and opened London’s first farmers’ market on June 6, 1999. The minister of agriculture rang the opening bell, Prince Charles (a keen organic farmer) sent a letter of congratulations, and all the major papers and the BBC turned up. The farmers, many of whom had never sold at retail, were doing a roaring trade. Soon they wanted more markets, and people in other neighborhoods were calling. By September, I’d opened two more, in Notting Hill and Swiss Cottage. In January 2000, I quit my job—by this time I was a speechwriter for the U.S. ambassador to Britain—to start more farmers’ markets.

After many years as a fairly dedicated vegetarian, I had begun to eat fish, partly because I had a great fishmonger, but probably more because the experts said fish was good for you. In 1999, a terrific book on brain chemistry, Potatoes Not Prozac, persuaded me to eat eggs again and to cut back on juice, honey, and white flour. Very quickly, I felt better and began to need new, smaller clothes. But I was still fat- and cholesterol-wary, quite afraid that meat, butter, and eggs would give me a heart attack.

My own farmers’ markets rescued me. Here was real food on my doorstep, just like at home—only better, because there were also new foods I’d never eaten: dried beef, pork pie, crème fraîche. Overnight I stopped using the supermarket, except for things like olive oil, chickpeas, and chocolate. For The Farmers’ Market Cookbook, I wrote recipes for beef, lamb, pork, poultry, even rabbit—and ate them all. Without really trying, I stopped thinking about food and started tasting it. Beef and lamb didn’t thrill me (yet), but I loved roast chicken and bacon. I never meant to lose weight, only to eat more real foods (more ice cream, less nonfat yogurt) and tastier ones (more chicken, less tofu). The pounds did their proverbial melting as I swapped rice and beans for roast chicken, bacon, and cheese.

My other complaints disappeared too, along with the colds and flu. As a vegetarian, I would have scoffed at the idea that my diet was anything but ideal. Now it’s clear my body was depleted of protein, saturated fat, fish oil, and vitamins K2, A, B, and D. Among other virtues, protein and fish help keep you trim, B vitamins and fish prevent depression, vitamin A aids digestion, and saturated fats boost immunity. I knew nothing about that, of course, only that the more meat, fish, butter, and eggs I ate, the better I felt. Health and good cheer restored, I became curious about the claims for a vegan and vegetarian diet. What I learned surprised me: we are not natural vegetarians—and no traditional culture is vegan over many generations.

Humans are omnivores, meant to eat everything from leaves and fruit to meat and eggs. Our anatomy is a hybrid of the herbivore and carnivore, with flat molars to chew vegetables and sharp teeth to tear into meat. Our digestive tract is neither very short (like a dog’s) nor very long (like a cow’s), but somewhere in between. All over the world, omnivores eat different foods: fish on the coasts, caribou in the woods, beef on the range. But dinner for a cow (grass) or a tiger (meat) is the same everywhere.

For about three million years, we ate mostly animal foods—as a percentage of calories, much more than today. Early humans

had a particular taste for bone marrow, brain, fish, and organ meats—and with reason. Marrow contains monounsaturated fats, brain is rich in polyunsaturated fats, fish is the only source of vital omega-3 fats, and liver has loads of iron and vitamins.

This preference for rich food—rather than the leaves and bark other primates ate—had a profound effect, turning us into Homo sapiens: the thinking ape. Relative to body weight, we have the biggest brains of all animals. Our brains grew bigger rapidly, easily outpacing more vegetarian primates, says William Leonard, a professor of anthropology at Northwestern University. “Brain expansion almost certainly could not have occurred until hominids adopted a diet sufficiently rich in calories and nutrients.”2 With primates, the general rule is: the bigger the brain, the richer the diet.

We humans are the extreme example of this relationship. Modern hunter-gatherers get 40 to 60 percent of calories from animal fat and protein, compared with a mere 5 to 7 percent for chimps. Our brain is not only big but also ravenous, using sixteen times more energy than muscle by weight. What does the brain need to run smoothly? Fats, especially fish oil. The brain is an astonishing 60 percent fat, of which half is docosahexaeonic acid (DHA).3DHA is found only in fish. Much of the fat coats the nerves like rubber insulation coats electrical wires. The myelin sheath is composed of lipids, including cholesterol.

The simple truth is this: there are no multigenerational traditional vegan societies. People everywhere search high and low for animal fat and protein because they are nutritionally indispensable. Frugal cooks use small amounts of meat and fat to supplement the vegetables, grains, and beans that provide most of the calories. Think of collard greens with fatback in the American South, Latino refried beans with lard, and the Asian stir-fry with a little pork and lots of rice. Cooks know that gelatin-rich bone broth extends the poor or scant protein in plants. Even vegetarian societies prize either dairy or eggs. Indian cuisine relies on eggs, yogurt, and ghee (clarified butter); Hindus call foods cooked in ghee pukka (authentic or superior) and foods in vegetable oil kachcha (inferior).

The vegan diet is unnatural and rare because it’s risky, especially for babies, children, and pregnant and nursing women. “When women avoid all animal foods, their babies are born small, they grow very slowly and they are developmentally retarded,” said Lindsay Allen, director of the U.S. Human Nutrition Research Center. “There’s no question that it’s unethical for parents to bring up their children as strict vegans.”4 Vegans risk deficiency of three critical nutrients: high-quality protein, vitamins, and fish oil.

The body uses protein for structure (muscle, bone, blood) and operations (enzymes made of protein run the whole body). A cow can live on grass, but omnivores need complete protein and they must get it daily because it cannot be stored. Most plants contain some protein—some, like beans, a fair amount—but all plant protein is incomplete. Protein is made of twenty amino acids, nine of which are called essential because the body cannot make them. All plants lack one or more of the twenty amino acids, or contain too little of one. Soybeans, for example, have all the amino acids but not enough methionine; corn needs more lysine and tryptophan. Wheat protein eaten alone, for example, may result in less-efficient use of nitrogen. Protein needs are unforgiving: when the diet lacks amino acids, the body ransacks its own tissue to find them.

Incomplete plant proteins can be combined to make complete protein to avoid the limitations caused by the lack of sufficient quantities of certain amino acids. Famous pairs are wheat and milk and rice and beans, and it now appears one doesn’t have to consume the pairs at the same meal, as vegetarians were once told. Yet this is still second-best nutritionally, for even when combined, plant protein is always inferior to animal protein, in quantity (there’s more protein per calorie in fish than in rice and beans) and in quality. Unlike plants, meat, fish, milk, and eggs contain amino acids in the ideal amounts for human health.

VEGETARIAN MYTHS

|

Myth: |

Our primate cousins are vegetarians. |

|

Truth: |

All primates eat some animal fat and protein. We eat more to feed our big brains. |

|

Myth: |

We are natural herbivores. |

|

Truth: |

We are omnivores with bodies designed to eat plant and animal foods. |

|

Myth: |

Historically we ate less meat. |

|

Truth: |

Historically we were even more carnivorous than today. |

|

Myth: |

Other cultures are vegan. |

|

Truth: |

There are no traditional vegan societies. Even vegetarian cultures use butter and eggs. |

|

Myth: |

We don’t need animal protein. |

|

Truth: |

Omnivores need complete protein every day. A small amount will do. |

|

Myth: |

Plant protein is as good as animal protein. |

|

Truth: |

Plant protein, even when combined to provide all the amino acids, is inferior to the protein in meat, fish, dairy, and eggs. |

|

Myth: |

Soybeans contain complete protein. |

|

Truth: |

Soybeans contain all the amino acids but not enough of one (methionine). |

SOURCES: Loren Cordain, The Paleo Diet; Weston A. Price Foundation; Joann Grohman, Real Food; and www.beyondveg.com.

Deficiency of essential vitamins is a risk of plant-based diets. Vitamin B6 is found in small amounts in plants, while chicken, fish, and liver are rich sources; vitamin B12 is found only in animal foods.5 Only animal foods (especially seafood, liver, butter, and eggs) contain true vitamins A and D. Animals can make vitamin A from beta-carotene in grass; cows are particularly efficient. Humans, too, can make vitamin A from beta-carotene, but with much more effort. The conversion requires bile salts, fats, and vitamin E. Babies, children, diabetics, and those with thyroid disorders are poor converters. Humans can make some vitamin D in the skin from cholesterol and sunlight when it hits the skin directly, but many people, surprisingly, don’t get enough sunlight, especially people with dark skin.

The gravest risk of a strict vegan or vegetarian diet is deficiency of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and DHA, found only in fish. In theory, the body can make these polyunsaturated fats from plants (flaxseed and walnut oil), but humans, especially babies, aren’t very good at it. Loren Cordain, a professor at Colorado State University and an expert in prehistoric diets, says that low DHA in mother or baby causes behavioral, mental, and visual problems in infants. Studies show that vegan breast milk is deficient in DHA.6 Other risks are low birth weight and premature birth.7

As an advocate for omnivory, I’m often asked whether I’m aware that expert bodies such as the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly the American Dietetic Association), a trade group representing seventy-five thousand registered dieticians and other nutrition professionals, endorses vegetarian and vegan diets. Yes, I am. A position paper on plant-based diets, published in the AND journal in 2009, concludes that “appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide benefits.”

This assertion is less impressive after you read the fine print. A critical appraisal reveals the evidence in the paper on vegan diets, in particular, to be quite weak vis-à-vis the strength of its conclusions. I raised an eyebrow when the authors explicitly conflated vegetarian and vegan diets: “the term vegetarian will be used to refer to people choosing a lacto-ovo, lacto-, or vegan” diet. Perhaps the authors chose this approach because good studies comparing omnivorous, vegetarian, and vegan diets are scant. But it would be more accurate to evaluate diets containing eggs, dairy, or both, and plant-only diets separately because there are substantial differences in available nutrients.

The Academy paper presents concerns about key nutrients for vegans, including calcium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, iodine, EPA, and DHA, and recommends fortified foods and supplements such as fortified orange juice, rice and soy drinks, breakfast cereals, and synthetic EPA and DHA derived from fungus and algae. This suggests that a vegan diet is neither natural nor traditional for humans. Although vitamins and fortification have probably contributed to public health, evidence grows that nutrients inherent in whole foods are superior to synthetic nutrients extracted from foods.

All told, the paper makes a good case that purely vegan diets pose some risks. For example, it offers evidence that vegans may not get adequate calcium and vitamin D; vegans have a higher risk of bone fractures; vegan diets are often rich in oxalates (in spinach and Swiss chard) and phytates (in seeds, including rice, nuts, and soy), which inhibit calcium absorption; no plant food (including fermented soy) contains a significant amount of active vitamin B12; vegan diets, often rich in folates (from leafy vegetables), may mask the symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency; iron needs are greater in vegans because plant-based iron is less bio-available than iron from foods of animal origin; and finally, in vegans, conversion of ALA (the plant-based omega-3 fatty acid found in walnuts) to EPA is substantially less efficient than in omnivores.

In a helpful note, the authors rated the quality of the evidence on which each of the paper’s concluding statements were based, from Grade I (Good) to Grade II (Fair) to Grade III (Limited) to Grade IV (expert opinion only, which I take to mean there are no studies) to Grade V (Unassignable), because “there is no evidence to support or refute the conclusion.” With these ratings to hand, things get interesting.

Every nutritionist knows that reproduction cycle and periods of rapid growth and development, e.g. childhood, make high demands on nutrients. So when the authors assert that vegan diets “are appropriate for individuals in all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence,” one immediately wants to assess the quality of the related evidence for each of the five stage of the life cycle listed. Fortunately, the authors do just that. On macronutrient and energy intake in pregnant vegans? There are no studies. Quality of the evidence: Grade V, or nonexistent. How about birth outcomes, such as length and weight? No studies looked at pregnant vegans. Another Grade V, for nothing. It appears that by the authors’ own standards, there is insufficient evidence to endorse vegan pregnancy. In pregnant vegetarians, the authors report lower intake, or lower blood levels, of several nutrients key to maternal and fetal health, including vitamin B12, vitamin C, calcium, zinc, iron, and DHA.

The authors place special emphasis on the omega-3 fats found only in foods of animal origin, such as fish, grass-fed milk and beef, and pastured eggs. “Infants of vegetarian mothers appear to have lower cord and plasma DHA than do infants of nonvegetarians. Breast milk DHA is lower in vegans and lacto-ovo-vegetarians than non-vegetarians. Because of DHA’s beneficial effects on gestational length, infant visual function, and neurodevelopment, pregnant and lactating vegetarians and vegans should choose food sources of DHA (fortified foods or eggs from hens fed DHA-rich microalgae or use a microalgae-derived DHA supplement.” Furthermore, “supplementation with ALA, a DHA precursor, in pregnancy and lactation has not been shown to be effective in increasing infant DHA levels or breast milk DHA concentration.”

What does the research say about vegan diets for infants, children, and adolescents? The paper finds evidence that vegetarian teens eat more produce than non-vegetarian peers, which is certainly good news. But the authors are quite clear on one point. “The safety of extremely restrictive diets such as fruitarian and raw foods diets has not been studied in children. These diets can be very low in energy, protein, some vitamins, and some minerals and cannot be recommended for infants and children.” The authors do not explain how a diet exclusively of plants differs from the “extremely restrictive diets” mentioned above. Elsewhere, they note that “little information about the growth of nonmacrobiotic vegan children has been published,” and once again recommend supplements for babies, children, and teens.

To my eye this paper, often cited as a bulletproof, official defense of a vegan diet, is unconvincing. Far from persuading me that vegan diets are suitable for all phases of the life cycle—or causing me to reconsider my understanding that humans are omnivores—instead it underscores the risks of an all-plant diet without supplements; indicates the dearth of evidence on various health measures of vegans; and reports evidence that vegan and vegetarian women do not have adequate EPA and DHA intake during pregnancy and lactation.

Why the paper is so weak, I cannot say. Perhaps there is better evidence for vegan diets in pregnancy, lactation, infancy, and adolescence, and the authors did not find it. I am unaware of any bias, either on the part of the individual authors or the Academy itself, in favor of vegan diets, but in recent years, I have become skeptical of the Academy’s integrity on nutrition generally, and many of its dietician members feel the same way. In 2015, Kraft Foods Group paid the Academy to put its “Kids Eat Right” label on Kraft singles, its famous stackable, rubbery sheets of “pasteurized cheese product.” The Academy has long been criticized for its too-cozy relationships with the industrial food behemoths, such as PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, and Kellogg’s, which fund its work. Jon Stewart sums it up: “It turns out the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics is an academy in the same way [Kraft singles] is cheese.”

Having dived into the science, I found the facts about vegan diets sobering, and felt intensely grateful to my omnivorous mother. When I was pregnant and nursing, I ate lots of beef, butter, and wild salmon, and if my kids get ideas about being vegan, I’ll do my damndest to talk them out of it. An adequate vegetarian diet, however, is possible, if it includes complete protein, plenty of flaxseed oil, and vitamins A, B12, B6, and D. If you must be a vegetarian, do eat butter and eggs for the protein and vitamins, and flaxseed and walnuts for ALA. Better still, eat fish, too.

Back in 1999, I knew nothing of chimp diets or vitamin A or why babies need fish. Farmers’ markets, not nutrition textbooks, restored my appetite for real food. As I ate my way through the English landscape, discovering local delights like the unctuous smoked eels of Somerset, I wondered: is there an ideal diet for omnivores? In the 1920s, a Cleveland dentist named Weston Price had the same question.

I DISCOVER WESTON PRICE AND HIS ODD NOTIONS

Of all the sights at a farmers’ market, there was none quite like that of Susan Planck in her heyday, hell-bent on selling two truck-loads of vegetables in four hours. Now in her midseventies, my mother is lean and fit, and until her last market day she had more energy than her crew of eight workers put together. Though she often had a scant five hours of sleep, she moved lightly and quickly, hefting a bushel of red peppers here, changing a price there. She’d call out: “We’ve had perfect weather for lettuce … This is the last week for strawberries!” My mother has a talent for education. From her signs, handouts, and books-to-borrow, customers learned about everything from soil minerals to breast-feeding.

She’s also a sponge for information, so I wasn’t surprised when someone at the Falls Church Farmers’ Market brought her an article by Sally Fallon called “Why Broth Is Beautiful.” Fallon said that stock from beef, poultry, and fish bones is rich in calcium and other minerals, in a form easily assimilated. Broth is also a protein sparer; it is easy to digest and facilitates digestion of everything else. Because it’s tasty and nutritious, broth is a key ingredient for frugal peasants and great chefs alike. Fallon called for a “brotherie” in every town serving veal stock, chicken soup, and beef consommé. I’ve wanted to start a place called Brothel ever since.

My mother wasted no time buying two copies of Fallon’s cookbook, Nourishing Traditions, sending one to me in London. Many of the recipes were for classic dishes (pot roast, Dover sole with cream sauce), but it was unusual in other ways. She cooked with sweetbreads, extolled lacto-fermented foods, and was keen on raw milk and raw liver. The book had high praise for meat, poultry, game, organ meats, eggs, and dairy from animals raised on grass, as well as wild fish and seafood including roe. Above all, Fallon was madly enthusiastic for saturated fats, especially butter and coconut oil.

Fallon, I learned, had founded the Weston A. Price Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to the work of Weston Price. Chicken broth sounded pretty good, but I wasn’t so sure about butter and lard, so I decided to read the five-hundred-page study Price published in 1939 to see for myself. Nutrition and Physical Degeneration is a classic work of anthropology, nutrition, and disease prevention. It’s also quite a story, and it made me think again about real food.

Weston Price was born in Ontario in 1870 and raised on a farm. He became a dentist and moved to the United States, where he practiced, did research, and wrote respected dentistry textbooks. Price was dismayed at the health of his American patients. Adults suffered from tooth decay and chronic diseases, including arthritis, osteoporosis, and diabetes. Kids had crooked teeth, deformed faces, asthma, infections, allergies, and behavioral problems. The dentist suspected his patients were malnourished on industrial foods, and set out to examine diets in isolated cultures, where people still ate what he called native foods.

Price went to preindustrial communities from Canada to Papua New Guinea, studying the diets of Gaelic fishermen, Ugandan shepherds, and Swiss dairy farmers. All over, he found people with beautiful teeth, perfectly formed faces, and little or no tooth decay—even though they had no dentists or toothbrushes. They were in fine overall health, with none of the chronic illnesses and diseases he saw at home. When they changed their diets, however, and ate what Price called “the displacing foods of commerce”—the sugar and jam, white flour and white rice, and refined vegetable oils that came on ships with European settlers—their health declined sharply.

People who began to eat industrial foods had crooked, crowded, and cavity-ridden teeth and suffered from chronic and fatal diseases including arthritis and tuberculosis. Children of parents who ate refined foods were born with poorly developed facial structure and other deformities like clubfeet. The facial differences in the photos Price took are striking. The unhealthy faces are narrow and asymmetrical, while the healthy ones are broad and shapely. In nature, symmetry is a signal of good conditions (typically nutrition) during growth and development. The human face is no exception.

Price was curious: what did these people eat to stay healthy? First, they ate local foods, which meant the diets in different environments varied widely. The communities were roughly of three types: dairy farmers and shepherds; fishermen; and hunter-gatherers.

In Swiss dairy villages, they ate whole raw milk, cream, and butter; whole-grain rye bread or grains of roasted rye; meat on Sundays; soups made with bone broth; and a few summer vegetables. In India and Tibet, they drank tea with milk and butter from sheep and naks—the female yak. Mountain shepherds in Egypt ate butter, which they also traded for millet with farming tribes from the plains. Herding tribes, such as the Masai in Kenya and the Muhima in Uganda, ate mostly meat, blood, and whole milk.

In fishing communities in the Outer Hebrides, remote islands off Scotland, people ate fish, roe, broth, and whole oats. Baked codfish heads stuffed with oats and chopped fish liver were especially popular. Alaskan Eskimo ate mostly seafood, including roe, seal, and whale. They ate no fruit and few vegetables—just a little kelp, cranberries, flowers, and sorrel preserved in seal oil. South Seas islanders and New Zealand Maori ate fish, shark, octopus, shellfish, and sea worms; wild pig and lard; and coconut, manioc, kelp, and fruit.

Hunter-gatherers all over—from Canada to the Everglades, the Amazon to Australia—had the most diverse diet. They ate game, including liver, glands, blood, and marrow; small animals, birds, and insects; and grains, tubers, and vegetables. Indians in the Canadian Rockies, where temperatures fell to seventy degrees below zero, ate no grains, dairy, fruit, or fish. They feasted on caribou and moose and prized moose adrenal glands. In the Andes, Peruvian tribes ate llamas, alpacas, guinea pigs, potatoes, corn, beans, and quinoa, a native grain. Australian Aborigines scrounged anything they could from the harsh landscape: roots, stems, leaves, berries, grass seeds, and a native pea; birds and eggs; seafood and freshwater fish; kangaroo and wallaby; and a variety of small animals and insects, including rodents, grubs, and beetles. Price made no effort to disguise his admiration for the resourceful Aborigines.

The dentist hoped to find people who lived on land-based foods alone, but he was disappointed. Even when at war, isolated hill people traded (by night, with special dropoffs) with coastal tribes for dried fish roe. Price knew seafoods were rich in iodine, which prevents goiter, mental retardation, and infertility, and in vitamins A and D, which aid the absorption of calcium and phosphorus, but he didn’t know about vital omega-3 fats found only in fish.

Price concluded there were four factors common to all the diets: whole foods, especially grains; the lack of refined flour and sugar; abundant meat and fish; and unrefined fats. Meat, fish, and fat were vital. Masai and Inuit were almost pure carnivores, and even the few largely vegetarian groups he found ate insects, grubs, and fish when they could. Diets contained all three types of the natural fats: saturated fats from butter, beef, and coconut oil; monounsaturated fats from bone marrow and lard; and polyunsaturated fats in fish and game.

Though Price didn’t draw attention to food preparation methods, they were important in traditional diets. Everyone ate raw foods, especially meat, blood, liver, fish, and milk. Raw foods are rich in vitamins, enzymes, and beneficial bacteria. They all favored lacto-fermented foods, including milk, grains, juice, and vegetables. Fermentation, a traditional form of preservation, enhances nutrition and aids digestion.

When Price analyzed the foods in his lab, he found that the traditional diets contained ten times more vitamins A and D than the American diet of his day and vastly more minerals, including calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, iodine, and iron. The Eskimo diet contained forty-nine times more iodine than the foods of the colonists.

BUT WE DON’T EAT GRUBS!

Hunter-gatherer diets (historical and contemporary) include foods we may find unappealing, like whale skin and salmon milt. Many tribes eat fat and protein raw, including blood, liver, and fish. For calcium, they crunch through bones in fish and small birds and savor pungent fermented foods. They eat these foods for vitamins, minerals, and enzymes. Happily, we can get the same nutrients from foods more familiar to the European-American palate. Caesar salad contains raw egg, aged Parmesan Reggiano, and anchovies, a fermented fish we eat whole, bones and all. Smoked salmon, steak tartare, and mayonnaise are three famous dishes of raw fish, meat, and eggs. Classic eggnog is made with raw egg and raw cream. It’s not necessary to eat exactly like a hunter-gatherer, only to obtain the nutrients they knew they needed.

Back home, Price set out to cure the unhealthy children in his clinic with good food. Their typical diet contained mostly refined foods: black coffee with sugar, white bread and pancakes, donuts fried in vegetable oil. In one experiment, Price fed malnourished kids one meal daily, six days a week, while they ate as usual at home. The therapeutic meals included liver, fish chowder, or a meat stew made of broth and carrots; a buttered whole wheat roll made with freshly ground flour; tomato juice with cod-liver oil; and two glasses of whole milk. The meat, dairy, and eggs came from animals raised on grass, which Price had found contained more vitamin A than animals raised on grain. It was the American version of the traditional diets: rich in protein, vitamins A, B, and D, omega-3 fats, and minerals. The children’s health—and their performance in school—improved sharply. “A properly balanced diet,” Price wrote, “is good for the entire body.”

THE FERTILITY DIET

In traditional diets, special foods were reserved for couples before conception and for women during pregnancy. Key nutrients include calcium, iodine, zinc, vitamin A, and omega-3 fats. Peruvian tribes in the Andes traveled hundreds of miles to trade with valley tribes for kelp and salmon roe, for iodine, vitamin A, zinc, and omega-3 fats. Alaskan Inuit ate dried fish eggs for fertility, while in North America, Indians ate the iodine-rich thyroid glands of the male moose. In Africa, the largely vegetarian Kikuyu fed girls extra animal fat for six months before marriage. In dairy villages, the fertility diet included raw spring-grass butter for vitamins A and D.

Today doctors tell pregnant women to take folic acid to prevent the birth defect spina bifida, but few couples are advised to eat a preconception diet. The first thing a woman needs to conceive is enough estrogen (in her fat) to ovulate. Men and women who would be parents should eat plenty of foods containing zinc, omega-3 fats, and vitamin A (needed to make estrogen). Eat cod-liver oil and butter, cream, egg yolks, and liver from grass-fed animals. Vitamin E is essential for sperm production; deficiency can cause permanent sterility. Sperm health improves dramatically when vitamins A and E are taken together, probably because vitamin E prevents oxidation of vitamin A. Protein and B vitamins, especially B12, are crucial for egg production, sperm count, and sperm motility. The omega-3 fat DHA is found in high concentrations in sperm.

Nutrition and Physical Degeneration was comprehensive, monumental—and controversial. Dentists and anthropologists welcomed the work—at one time, the book was on the reading list for anthropology classes at Harvard—but most medical professionals ignored it. Price himself noted frequently that his approach to disease was unorthodox. His work did, however, inspire the nutritionist Adelle Davis. Davis had a master’s degree in biochemistry from the University of Southern California Medical School, but she wrote about nutrition in a friendly, common-sense style. In the 1950s and ’60s, titles like Let’s Eat Right to Keep Fit and Let’s Get Well became bestsellers.

Growing up on a farm in Indiana, Davis ate a traditional American breakfast of hot cereal, steak, ham, eggs, sausage, and fried chicken with gravy, all washed down with grass-fed, whole milk—and that was exactly the food she recommended for a diet rich in protein and vitamins A, D, and B. Davis extolled whole grains, unrefined fats, whole milk, and plenty of protein, including beef, liver, fish, and eggs. She called for raw foods, including eggs, liver, and milk. Davis was ahead of her time; she wrote that hydrogenated fats were dangerous and fish oil reduces cholesterol.

Like Price, Davis was controversial. “She so infuriated the medical profession and the orthodox nutrition community that they would stop at nothing to discredit her,” recalls my friend Joann Grohman, a dairy farmer and nutrition writer who says Adelle Davis restored her own health and that of her five young children. “The FDA raided health food stores and seized her books under a false labeling law because they were displayed next to vitamin bottles.”

Price and Davis were pioneers in the field now known as nutritional epidemiology—the study of nutrition and disease—and modern research confirms their work. The experts now agree, for example, that hydrogenated vegetable oil, not butter, raises LDL. As we’ll see later, heart disease is caused by a diet deficient in B vitamins, not by saturated fats. Researchers even explore the subtle interplay between diet and how genes function. The omega-3 fats EPA and DHA, for example, activate the expression of genes controlling fat metabolism, which may explain how they prevent obesity. Hippocrates gave us the essence of nutritional epidemiology: “Let food be your medicine and medicine be your food.”

After I read about traditional diets, it was clear how my vegan, fat-free ways had depleted my body. But one thing was nagging me: whether eating saturated fat and cholesterol every day was really okay. Before I dived headfirst into traditional beef, butter, and eggs, it seemed sensible to find out what modern science had to say about them. I started to do some homework on real food.

EVERYWHERE I GO, PEOPLE ARE AFRAID OF REAL FOOD

At the Union Square Greenmarket in New York City, an older woman was buying chicken. “I can’t eat any skin,” she told the farmer firmly. “This is the best chicken on the market,” I chimed in, “because it’s raised on pasture. And the skin is good for you too, full of healthy fats.” She turned toward me, indignant. “I never eat the skin,” she said. “It’s bad for you, all that fat!”

At Murray’s, my husband’s cheese shop in New York City—the oldest—a young woman was asking for low-fat mozzarella. She prefers whole milk mozzarella, she said, but feels “less guilty” eating the skim milk version.

At home, we serve guests chicken, mashed potatoes with milk and butter, spinach salad with bacon, tart cherry pie with lard crust, and raw whipped cream. “There goes my cholesterol,” they joke. “Don’t tell my doctor!” Even as they dig into this delicious and satisfying food, they cannot forget that it’s going to kill them. “Heart attack on a plate,” says another. The tone combines fear, resignation, and guilty pleasure.

All these good people are wrong.

The woman at the farmers’ market doesn’t know that chicken fat is monounsaturated and polyunsaturated—two fats even the conventional experts say are healthy. Why would she? According to the experts, the less fat the better, and chicken fat is no exception. Schmaltz is a guilty pleasure. Here, the farmer is no help; he doesn’t know what’s in chicken fat, either. Chickens raised on grass contain more conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), an unusual fat which fights cancer and builds lean muscle. Chicken fat also boosts immunity. The Jewish penicillin wasn’t skinless chicken breasts; it was chicken soup, with droplets of golden fat that also make chicken soup silky. But someone taught this lady that chicken fat is poison—not her mother, I’ll bet—and she’s sticking to it.

The young woman at Murray’s doesn’t know that you need the fat in milk to digest the protein and absorb the calcium. If she struggles with her weight, she may discover—as million of Americans have, after thirty years of dubious advice—that eating foods engineered to be low-fat doesn’t work, especially when you eat more calories because the food is unsatisfying. Also, the latest research indicates that milk, yogurt, and cheese actually aid weight loss, perhaps due to the effects of calcium on fat storage.

At our house, we eat the way people did for thousands of years. That means all the foods they tell you to avoid: red meat, whole milk, sausage, butter, and raw milk cheese. But the beef and milk are mostly grass-fed, the pork and poultry mostly pastured, and the fats—from lard to coconut oil—are unrefined. Milk, cream, and butter are mostly grass-fed. I relish the rich, unfashionable cuts you never see in “heart-healthy” diets, such as liver and bone marrow—just as our Stone Age ancestors did. I don’t buy low-fat versions of anything. Foods should be eaten with the fats they come with: whole milk, chicken with skin.

All this real food is good for you. How?

*Grass-fed beef is rich in beta-carotene and vitamin E (both fight heart disease and cancer) and CLA, the anticancer fat.

*Grass-fed milk, cream, butter, and cheese are rich in vitamins A and D, omega-3 fats, and CLA. Butter contains butyric acid, another fat that fights cancer and infections.

*Pastured pork and lard are rich in antimicrobial fats and the monounsaturated fat oleic acid—the same fat in olive oil, which reduces LDL.

*Pastured eggs are rich in vitamins A and D. They contain omega-3 fats, which prevent obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and depression. Egg yolks contain lecithin, which helps metabolize cholesterol.

Cholesterol. This word alone can stop a story about food in its tracks. The thought of rich, sweet cream has barely taken shape before the evil ingredient cholesterol flutters by, landing smack-dab in the worry corner of the brain to spoil the reverie. I know what you’re thinking. Aren’t saturated fats and cholesterol dangerous? I don’t think so.

Let’s first agree that Americans are right to be worried about diet and health. Since 1900, once-rare conditions—obesity, diabetes, and heart disease—have become rampant. These three are known as the diseases of civilization, because for most of human history they were all but unheard of. (Three million years ago, if you were obese or diabetic or your heart failed, you would soon be dead.) In the United States today, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease are chronic diseases. They can be deadly, but just as often, they’re a condition people live with, thanks to a combination of drugs, surgery, and diminished quality of life—as in “I’m too fat and out of breath to play catch with my dog.” People with type 2 diabetes survive on insulin injections. In 1950, most heart attacks were fatal. But today, thanks to major medical advances, more Americans with chronic heart disease are living longer. Certainly, enabling people to live with chronic disease is a sign of progress. Preventing disease is another—the one that interests me here.

The reader might object that life in the Stone Age was different. For the hunter-gatherer couple, it was nasty, brutish, and short; he might be gored by a mastodon and she was apt to bleed to death while giving birth. We, on the other hand, live much longer, with ample time to grow old and to develop degenerative diseases. How do we know the meat-loving hunter-gatherers would not have keeled over from hardened arteries, too, had they managed to survive to sixty-five?

Good question. Loren Cordain, the expert in Stone Age diets, looked into this one. In most hunter-gatherer groups, 10 to 20 percent are sixty years or older—and in fine health. “These elderly people have been shown to be generally free of the signs and symptoms of chronic disease (obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels) that universally afflict the elderly in western societies,” he says. “When these people adopt western [industrial] diets … they begin to exhibit signs and symptoms of ‘diseases of civilization.’” So much for the idea that age equals disease.

Let’s next agree that the experts are right: diet does affect blood. The study of blood cholesterol and its various subcategories is getting more sophisticated by the hour, but the conventional wisdom holds that it’s better for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) to be high and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) to be low. Casually known as the “good” and “bad” cholesterol hypothesis, this idea emerged when it became clear that the number they call “total cholesterol” was a poor—very poor—predictor of heart disease. For decades, most experts asserted that low HDL and high LDL are “risk factors” for heart disease, which means the two conditions are statistically correlated.

But this proved a poor model for medical care. There are at least two important caveats to the rule that high LDL, in particular, is dangerous. The first is a lesson from Statistics 101: correlation does not necessarily imply cause. In other words, high LDL does not necessarily cause heart disease. Instead, it could be a symptom (or marker, as experts say) of heart trouble. The second caveat is equally serious: many studies show that high LDL and heart disease are not linked. In 2005, the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons reported that as many as half of the people who have heart disease have normal or “desirable” LDL.8 Also in 2005, researchers found that older men and women with high LDL live longer.9 When the rule—high LDL is dangerous—doesn’t apply in the elderly or in half of the heart disease cases, the honest scientist can only conclude one thing: the rule needs a second look. Some cholesterol experts believe the rule needs more than just tweaking. “There is nothing bad about LDL,” says Joel Kauffman, Professor of Chemistry Emeritus at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. “There never was.”10

What might account for the inconsistent findings on LDL and heart disease? First, the link some studies show between high LDL and heart disease could be explained by oxidation. Research in humans and animals shows that natural LDL is a normal part of a healthy body, but oxidized or damaged LDL is bad news. Perhaps high LDL readings really represent high oxidized LDL. Second, does cholesterol really clog arteries? Probably not. According to Kauffman, there is no relationship between total cholesterol (or LDL) and atherosclerosis. As we’ll see later, an amino acid called homocysteine, not cholesterol, actually damages arteries.

Later, we’ll look at cholesterol in more detail, but for now, let me say this: I believe the “good” and “bad” cholesterol story has failed to explain heart disease fully—and worse, it has failed to prevent it. The narrative of evil LDL and knightlike HDL oversimplifies a complex reality.

What about diet? Other things being equal, does eating foods like butter and eggs, rich in natural cholesterol and natural saturated fat, have an undesirable effect on blood cholesterol and lead to heart disease? From what I can gather, the answer is no. High cholesterol and heart disease are rare in cultures where people eat cholesterol-rich foods, including butter, eggs, and shrimp. The same is true in tropical cultures where they eat saturated coconut oil daily. Studies of traditional diets are only one reason I eat butter, cream, and coconut oil with impunity. Happily, clinical studies confirm this observation about saturated fats.

The story about diet and disease is more complicated than just saturated fats and cholesterol, of course. As we’ll see, reductionist thinking is precisely the mistake the experts, who focused everything on cutting fat and cholesterol, made. Traditional diets are also rich in many other nutrients that prevent heart disease, including omega-3 fats in fish and B vitamins. But one thing is clear: if beef and butter were to blame for heart disease, heart disease would not be new. We’ve been eating them for too long.

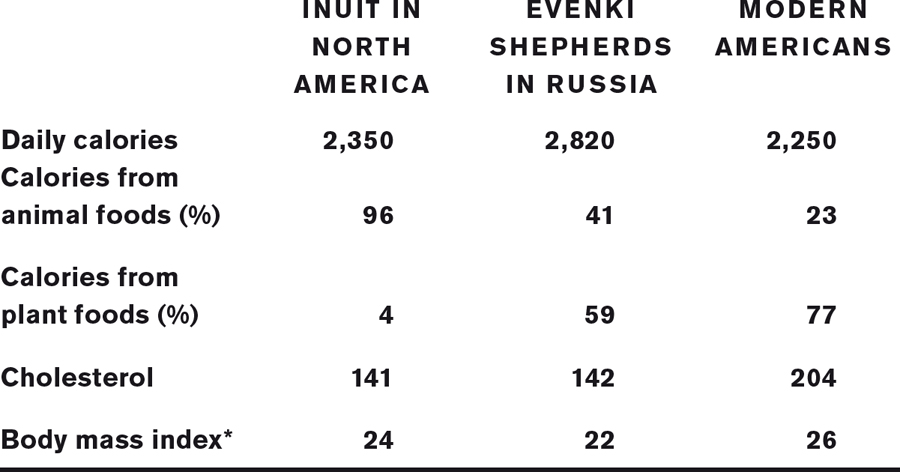

Look at the traditional diets in the accompanying table. They contain more calories, and many more calories from animal foods, than the modern American diet. Yet Americans are overweight with higher cholesterol levels. Evenki reindeer herders in Russia derive almost half their calories from meat, almost twice as much as the average American. Yet Evenki men are 20 percent leaner than American men, with cholesterol levels 30 percent lower.11

Clearly, the Americans are doing something wrong. Even though we eat fewer calories and more calories from plant foods than the Inuit and Evenki, we’re fat and have “high” cholesterol. The fault may well lie in our diets, but judging from these cases—and many similar studies of modern hunter-gatherers such as Australian aboriginals—it’s unlikely that saturated animal fat itself causes unhealthy cholesterol. These lean, healthy people eat a lot of saturated animal fat. Something else must be to blame for our own poor health.

What might that be? The culprit is industrial foods. Sugar and hydrogenated vegetable oils raise cholesterol and triglycerides. Eating oxidized—or damaged—cholesterol leads to unhealthy oxidized LDL in the body. The main, dietary source of oxidized cholesterol is powdered skim milk and powdered eggs, commonly found in processed foods. Finally, other factors are vitally important. Exercise, for example, keeps you thin and raises HDL. You can bet that Inuit seal hunters and Evenki shepherds get more exercise than most Americans.

MODERN AMERICAN DIET VERSUS TRADITIONAL DIETS

A healthy BMI is 18.5-24.9. Above 25 is overweight, and above 30 is obese.

SOURCE: William R. Leonard, “Food for Thought,” Scientific American, August 2003, Vol 13, No 2 (updated from the December 2002 issue).

The experts are right: our diet is killing us. But traditional beef, butter, and eggs are not to blame for obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. The so-called diseases of civilization are caused by the foods of civilization. More accurately, the diseases of industrialization are caused by the foods of industrialization.