The Business Blockchain: Promise, Practice, and Application of the Next Internet Technology - William Mougayar, Vitalik Buterin (2016)

Chapter 4. BLOCKCHAIN IN FINANCIAL SERVICES

“The worst place to develop a new business model is from within your existing business model.”

-CLAYTON CHRISTENSEN

FINANCIAL SERVICES INSTITUTIONS will be challenged by how much they are willing to bend their business models to accommodate the weight of the blockchain. Their default position will be to only slightly open the door, expecting to let as many benefits seep in, with the least amount of opening. The challengers (mostly startups) will try to kick that door open as much as possible, expecting to throw the incumbents off balance.

Much of the blockchain’s technological innovation in financial services is driven by startups. But financial institutions, like any other industry, can innovate by applying that technology. Startups are like a strange beast when it comes to how banks view them. They will first get examined and kept at close proximity, but benefits do not happen via symbiosis. In reality, large organizations are degrees removed from most startups. Their initial interest is like visiting animals in the zoo. The litmus test is to bring the technology home to see if it will survive domestication.

Any large organization will be challenged when facing large amounts of external innovation that surpasses their internal abilities to absorb it or usurp it.

Industry activities are coming from two different directions. On one hand, startups and technology products and services companies are entering the market. On the other hand, organizations will start to study the market and generate a long list of use cases and target areas. The challenge will be to match the right technical and business approaches to the chosen use cases, projects and initiatives.

Banks will be required to get their hands dirty and learn the new technologies directly. They will also need to get their minds dirty and try ideas even if they risk failing. The more basic experience they acquire early on, the faster they will be able to progress from their initial work to more ground-breaking undertakings.

This chapter does not prescribe specific solutions to specific organizations. Rather, it lays out how financial services organizations can think about the blockchain. How to think about the blockchain is useful, because it allows you to uncover your own strategies. After all, you know your business better than anyone else.

ATTACKED BY THE INTERNET AND FINTECH

To understand how the blockchain will affect financial services institutions, we must go back to their recent history with the Internet, and also look at the advent of FinTech companies that offered competing services by embracing a technology-forward product approach.

Banks have been relying on information technology (IT) since the early introduction of the mainframe computers in the late 1950s, but the term FinTech only became popular around 2013. It is ironic that technology has always played a key role in a bank’s operations, yet one could argue that banks did not innovate much with the Internet. Traditionally, the IT focus at banks was oriented towards running back-end operations (including clients’ accounts and transactions), supporting branch retail functions, linking automated teller machines, processing payments from point-of-sale retail gateways, being globally interconnected with their partners or inter-banking networks, and delivering a variety of financial products ranging from simple loans to sophisticated trading instruments.

In 1994, the Web arrived, and with it the potential to offer an alternative front-end entry point for any service. However, most banks pushed back on that innovation window, because they were entrenched in delivering services inside their retail branches, or via one-on-one business relationships. They did not see the Web as a catalyst for bigger change, so they adapted the Internet at their own pace, and according to their own limited assumptions. Fast forward to 2016, more than 20 years into the Web’s commercialization, and one could argue that banks only gave their customers Internet banking (with mobile access later), online brokerage, and online bill payments. The reality is that customers are not going to the branch as often (or at all), and they are not licking as many stamps to pay their bills. Meanwhile, FinTech growth is happening; it was a total response to banks’ lack of radical innovation.

PayPal was the quintessential payment disruptor. Thousands of FinTech companies followed their lead and started offering alternative financial services solutions. With 179 million active users and $282 billiion total payments volume by the end of 2015, PayPal was “a truly global platform that is available in more than 200 markets, allowing customers to get paid in more than 100 currencies, withdraw funds from their bank accounts in 57 currencies and hold balances in their PayPal accounts in 26 currencies.”1

PayPal has direct relationships with hundreds of local banks around the world, making them arguably the only global financial services provider that virtually knows no boundaries. PayPal’s success had fundamental implications: it demonstrated that alternative financial services companies could be viable, just by building bridges and ramps into incumbent banking institutions. As a side note, in 2014, ApplePay took a page from PayPal, and inserted itself once again between the banks and their customers by hijacking the point-of-sale moments via multipurpose smartphones. If you talk to any banker in the world, they will admit that ApplePay and PayPal are vexing examples of competition that simply eats into their margins, and they could not prevent their onslaught.

By 2015, more than $19 billion in venture funding had been poured into FinTech startups.2 Many of them were focused on just a few popular areas: loans, wealth management, and payments. Some startups have gone as far as offering full banking services via mobile-only, an approach that is appealing to millennials. This proves that a new form of bank can be created from scratch, without legacy baggage.

What is interesting is that FinTech startups didn’t initially attack incumbents head-on, knowing it is risky and costly. Rather, their entry points were in adjacent, uncontested, neglected, or underserved territories; they appear at first to be avoiding the incumbents. Startups begin small and look harmless. They are ignored, until they suddenly become significant and unstoppable.

This backdrop is important. Blockchain may follow the same trajectory as FinTech thus far, turning footholds into significant beachheads or fully-fledged businesses. Some blockchain-based startups are already slowly attacking pain points within the financial services market, offering solutions to existing players, while others are following a cooperative process to fertilize flavors of shared infrastructure or services solutions. Other startups are dreaming the impossible by ignoring incumbents, and offering new solutions to a virgin market.

Those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it. If banks do not adapt more radically than they did with the Internet, they will suffer the consequences. If FinTech was about challenging banks’ payments systems, blockchain promises to not only continue to unbundle the banks, but seems intent on disrupting a whole gamut of traditional inter-institutional processes, from cross border to clearinghouses.

For financial institutions, the future of blockchain technologies will begin via two parallel paths. It is a story of good and bad news. On the bad news side, some of the blockchain startups will be going after their business, FinTech style. But the good news is that blockchain technology is perfect for streamlining much of banking operations.

If you are an optimist, there is a third outcome. Banks and the entire financial services industry might decide to seriously reinvent themselves. In that difficult to achieve scenario, there will be winners and losers, and parts of the overall segment would shrink—but it might emerge stronger in the long term.

Blockchains will not signal the end of banks, but innovation must permeate faster than the Internet did in 1995-2000. The early blockchain years are formative and important because they are training grounds for this new technology, and whoever has trained well will win. The strong will not die. Banks should not only see the blockchain as a cost savings lever. It is very much about finding new opportunities that can grow their top line.

WHY CAN'T THERE BE A GLOBAL BANK?

To a skeptic, it sounds like a rhetorical question, given that Bitcoin was destined to become the underpinning nerve for a new type of global financial system that is borderless. Bitcoin’s vision is a globally decentralized money network with users at the edges of it.

We should ask the question—since Bitcoin is global and universal, why is not there a truly global Bitcoin bank?

This is a tricky question, because Bitcoin’s philosophy is about decentralization, whereas a bank is everything about centrally managed relationships. However, a global bank with no restrictions on borders or transactions would be interesting to users that want to conduct global transactions wherever they are in the world with the same ease as using a credit card.

But here’s the sad news: this fictitious global bank will never exist, because local regulatory hurdles are too high and too real. No existing startup or bank has the incentive or desire to become that “ultra” bank. The hurdles that Uber (the ride sharing service) has faced against the global taxi cartels would pale in comparison to the complexities and intricacies of the regulatory, compliance, and legal barriers that are intrinsic to each local financial services system around the world.

Do you know why HSBC is not really the world’s leading global bank, despite being in 72 countries? Do you know why Coinbase is not really the “world’s” leading Bitcoin exchange, despite being the largest and only exchange available in 27 countries?

There is a common answer to these two questions: regulatory restrictions. This means that your account’s capabilities are confined to the country you belong to, just like a traditional bank account. As a user, you do not really get the feeling of being global. HSBC and Coinbase may be global companies, but their customers do not have borderless services privileges.

Luckily, within a pure Bitcoin world, that potential global bank is you, if you are armed with a cryptocurrency wallet. A local cryptocurrency wallet skirts some of the legalities that existing banks and bank look-alikes (cryptocurrency exchanges) need to adhere to, but without breaking any laws. You take “your bank” with you wherever you travel, and as long as that wallet has local onramps and bridges into the non-cryptocurrency terrestrial world, then you have a version of a global bank in your pocket.

This backdrop about the evolution of consumer-based cryptocurrency trading is important, because it demonstrates that we can achieve another form of connectedness by virtue of the blockchain itself, achieving a SWIFT-like3 effect. The 50 or so cryptocurrency exchanges that exist in various parts of the world are not overtly linked together, yet they are seamlessly connected by the blockchain. This is a significant confirmation that a blockchain is a global network that knows no boundaries. As much as banks disdain Bitcoin and its blockchain, they should see these capabilities as a demonstration of what is possible if you let a blockchain become a global network.

One could argue that the cryptocurrency networks (enabled by blockchains) are going to be more important than the currency itself. New decentralized networks also allow the trading of any digital asset, financial instrument, or real world asset that is linked to a cryptocurrency-based token (a form of proxy attachment to a blockchain). Whether using a standalone wallet, or a brokerage type of account, users already have access to various familiar actions that we typically conduct with money: buy, sell, pay, get paid, transfer, save, or borrow. Incidentally, PayPal offers the same functions.

Maybe one day, we could each become our own virtual bank. Advanced cryptocurrency wallets could become to the world of crypto-finance networks what the browser was to the World Wide Web, and be these new entry points for monetary transactions. Hopefully, regulators can evolve with the technology without a heavy-handed approach, as long as users are not bad actors, pay their taxes, and do not conduct illegal activities.

Getting to a global bank status is not easy. There is a historical reminder that online banking is not enough to produce a global bank. Several attempts were made, from 1995-2000, to form Internet-only banks,4starting with Security First Network Bank (SFNB), the world’s first Internet bank, but each attempt was confined to the jurisdiction they were created in. SFNB, CompuBank, Net.B@nk, Netbank AG, Wingspan, E-LOAN, Bank One, VirtualBank and others are examples, but they did not survive the dot-com crash of 2000.

The new crop of online/mobile only banks and financial services startups such as Atom, Tandem, Mondo, ZenBanx, GoBank, Moven, and Number26, do offer a new generation of services that challenges traditional banks. But if any of these services aims to become global, they still need to knock down the local financial regulatory barriers.

If you were a millennial today, you would not think twice about not using a traditional bank because most of the services you are attracted to are offered by alternative financial services companies, primarily due to these innovative FinTech startups that sprung up in the past decade. A typical “millennial financial stack” includes an array of new FinTech services, and only the most innovative products from a traditional bank.5

Typically, we use traditional banking networks to transfer any type of money. I can see a future where we are using a blockchain infrastructure to transfer any money, including cryptocurrency and sovereign currency. This means that traditional money may be coming to cryptocurrency wallets and exchange brokerage accounts faster than cryptocurrency being accepted inside traditional online banking accounts.

BANKS AS BACKENDS

One likely future scenario is for banks to function as backends, or a lateral window, as we will be transacting and moving money externally via our smartphones, apps, cryptocurrency accounts, or Web services directly. Although a truly global bank or exchange may not happen any time soon, the feelings and behaviors of a global bank are needed.

In this scheme, banks become financial on-ramps and off-ramps, but they will not be centers of your wallet.

The more we link our bank accounts to external services and applications, the more we realize that we are living in a world of decentralized banking. The trend has started, and it is more than anecdotal because it is happening frequently and with increasing impact.

Here are some examples:

· If you run a ticketed event and collect fees from attendees, you can link that event’s payment process to your bank account and get paid quickly. For example, this is accomplished by linking Eventbrite via PayPal (as the payment processor) to your account.

· If your cryptocurrency exchange account is connected to your bank account, you could move money around the world in less than 10 minutes at the cost of pennies in fees, and then you (or the recipient) can transfer the money back and forth to a bank account. Most exchanges provide multiple ways to deposit or withdraw money, including wire transfers, drafts, money orders, Western Union, check, debit card, Visa, PayPal, or Virtual Visa, many of them for free. Some of these exchanges even offer foreign currency exchange services in real-time between a variety of cryptocurrencies and popular currencies, such the U.S. dollar, Canadian dollar, Euro, British pound, and Japanese yen. Already, these are more capabilities than what the average bank user can do without visiting a branch.

· If you are running a crowdfunding campaign (such as on Kickstarter), you are also required to link your bank account. At the completion of a successful campaign, your earnings are automatically deposited into that account.

· When you link your ApplePay account to checkout and pay for items in seconds, the money is actually coming directly from one of your bank or credit card accounts.

· When you take an Uber ride, Uber makes a pull request to charge your credit card, automatically.

· A Venmo account that lets you receive money instantly from a friend, also lets you push that balance back to your bank account (or vice-versa).

These examples are few but significant. The point and reality of all these situations is that we, as consumers, are doing more interesting things with these new ancillary services than we can directly from our bank accounts. More importantly, the banks alone would not allow us to accomplish what these linkages enable, which is why we have to go through these new intermediaries. These new services are liberating us from the restrictive features of a traditional bank account.

Retail merchants have had a taste of this two-tier separation for a while, via their point-of-sale terminals that take money from customers and see it automatically deposited in their bank accounts. That was their version of linked services, but now this is more widely expanded to consumers.

Concurrently, the pendulum is swinging between local and global linkages. Traditionally, banks have had strong local anchors because that’s how they were started. Later, they built global linkages between them at great expense and effort, through networks that are proprietary and relatively expensive to maintain. But with the advent of Bitcoin and blockchains as global rails, we already have powerful global networks that are seamless across boundaries, and we are now complementing the reach of those new networks by adding local anchors and local users, via your bank account. Suddenly, your traditional bank account will ressemble nothing more than a node on the global cloud of financial networks.

Strongly operating locally has killed the banks’ abilities to join the more open global Web of financial services—except through on-ramps and off-ramps—and no longer function as the main money highway. Banks risk being on the outside looking in, if they continue allowing more on-ramps and exits to the new world of cryptocurrencies. Otherwise, they will become islands themselves.

Although regulation has offered consumers some personal protection benefits, the natural regulatory reactions are to continue erecting higher barriers for local entry (for competitive reasons), resulting in pushing users to more global and seamless services because the game is now happening via the web’s interstitials.

The decentralization of banking is here. It just has not been evenly distributed yet.

BLOCKCHAIN INSIDE REGULATIONS VERSUS PERMISSIONLESS INNOVATION

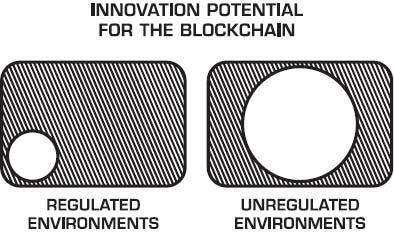

The distinction between permissionless blockchains (ones that are public and open for anyone’s participation), and permissioned blockchains (ones that operate in private settings, via an invitation-only model) is correlated to the degree of innovation that follows.

The default state and starting position for innovation is to be permissionless. Consequently, permissioned and private blockchain implementations will have a muted innovation potential. At least in the true sense of the word, not for technical reasons, but for regulatory ones, because these two aspects are tied together.

We are seeing the first such case unfold within the financial services sector, that seems to be embracing the blockchain fully; but they are embracing it according to their own interpretation of it, which is to make it live within the regulatory constraints they have to live with. What they are really talking about is “applying innovation,” and not creating it. So, the end-result will be a dialed-down version of innovation.

That is a fact, and I am calling this situation the “Being Regulated Dilemma,” a pun on the innovator’s dilemma. Like the innovator’s dilemma, regulated companies have a tough time extricating themselves from the current regulations they have to operate within. So, when they see technology, all they can do is to implement it within the satisfaction zones of regulators. Despite the blockchain’s revolutionary prognosis, the banks cannot outdo themselves, so they risk only guiding the blockchain to live within their constrained, regulated world.

It is a lot easier to start innovating outside the regulatory boxes, both figuratively and explicitly. Few banks will do this because it is more difficult.

Simon Taylor, head of the blockchain innovation group at Barclays, sums it up: “I do not disagree the best use cases will be outside regulated financial services. Much like the best users of cloud and big data are not the incumbent blue chip organizations. Still their curiosity is valuable for funding and driving forward the entire space.” I strongly agree; there is hope some banks will contribute to the innovation potential of the blockchain in significant ways as they mature their understanding and experiences with this new technology.

An ending note to banks is that radical innovation can be a competitive advantage, but only if it is seen that way. Otherwise, innovation will be dialed down to fit their own reality, which is typically painted in restrictive colors.

It would be useful to see banks succeed with the blockchain, but they need to push themselves further in terms of understanding what the blockchain can do. They need to figure out how they will serve their customers better, and not just how they will serve themselves better. Banks should innovate more by dreaming up use cases that we have not thought about yet, preferably in the non-obvious category.

LANDSCAPE OF BLOCKCHAIN COMPANIES IN FINANCIAL SERVICES

At the end of 2015, I published a detailed landscape of blockchain companies in financial services,6 and tallied 268 entries, across 27 categories. I followed it with an analysis of the sector by releasing another popular slide deck7 that gathered 175,000 views on Slideshare within a month of being published.

The landscape of blockchain companies that are targeting financial services can be divided across three sectors:

· Infrastructure and Base Protocols

· Middleware and Services

· Applications and Solutions

The following table details the various players, and the market forces at play.

|

APPLICATIONS AND SOLUTIONS |

|

|

|

|

MIDDLEWARE & SERVICES |

|

|

|

|

INFRASTRUCTURE & BASE PROTOCOLS |

|

|

|

BLOCKCHAIN APPLICATIONS IN FINANCIAL SERVICES

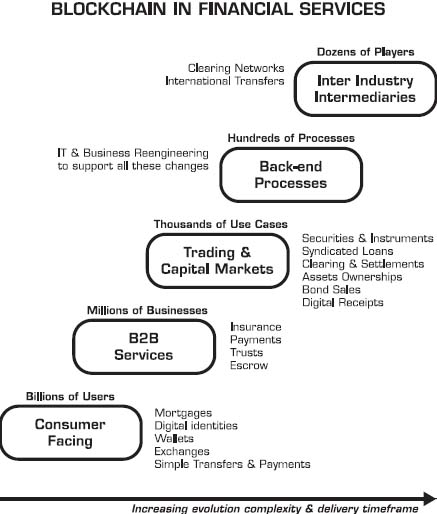

From an internal implementation point of view, the blockchain’s evolution in Financial Services will happen according to a progressive segmentation of major applications areas:

· Consumer facing products

· B2B services

· Trading and capital markets

· Back-end processes

· Inter-industry intermediary services

The following diagram illustrates how these categories might unfold along an increasingly complex timeframe of implementation.

It is worth highlighting some practical approaches that are beginning to emerge, and are pointing towards the future:

· In November 2015, ConsenSys demonstrated a two-party Total Return Swap financial contract that made use of underlying identity, reputation, and general ledger components, and ran on the Microsoft Azure cloud platform.

· In February 2016, Clearmatics announced it was developing a new clearing platform for over-the-counter derivatives that it calls a Decentralized Clearing Network (DCN). It allows a consortium of clearing members to automate contract valuation, margining, trade compression, and close-out without a central clearing counterparty (CCP), or third-party intermediation.8

· In March 2016, forty of the world’s largest banks demonstrated a test system for trading fixed income, using five different blockchain technologies (as part of the R3 CEV consortium).

· In March 2016, Cambridge Blockchain designed a catastrophe bond transaction process that included counterparty validation on the blockchain, and an automated workflow enabling users to maintain privacy while selectively revealing limited attributes of their identities required for pre-trade authentication and compliance.

What is common to each of the above cases, is that these transactions were done from start to finish on a peer-to-peer basis, without central intermediaries or clearinghouses in the middle. The counterparties did not need to know each other or require a third-party to intermediate the transaction. Decentralization and peer-to-peer transaction finality are key blockchain innovations that must be preserved in order to maximize the potential impact of blockchain implementations. Generically, the counterparties’ identities and reputations are automatically verified on the blockchain via wallet addresses or built-in AML/KYC (Anti-Money Laundering / Know Your Customer) attestations or collateral requirements. Then, the transaction terms are entered into a smart contract and published on the blockchain, while simultaneously storing the associated regulatory agreement (for example, an International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) Master Agreement) on a decentralized peer-to-peer file distribution protocol (for example on the InterPlanetary File System). The last reporting step could be entered into a standard database performing compliance requirements, although the degree of P2P purity would be diminished if centralized databases are used.

There are many applications where a blockchain or distributed consensus ledger solution will make sense. At the risk of not naming all of them, here are the largest segments that will affected:

· Bonds

· Swaps

· Derivatives

· Commodities

· Unregistered/Registered securities

· Over-the-counter markets

· Collateral management

· Syndicated loans

· Warehouse receipts

· Repurchase market

STRATEGIC QUESTIONS FOR FINANCIAL SERVICES

Theme 1: Blockchains Touch the Core of Banking, Can They React?

In Chapter 2, we introduced the word ATOMIC as a way to remember the programmability aspect of blockchains along six interrelated areas: Assets, Trust, Ownership, Money, Identity, Contracts. Add to these concepts the fact the blockchain is about decentralization, disintermediation, and distributed ledgers, and you quickly realize that these subjects are very much part of the core of banking. When a single technology touches almost every core part of your business model, you need to pay attention, as it will be a challenging encounter. Banks will be required to apply rigorous thinking to flush out their plans and positions vis-à-vis each one of these major blockchain parameters. They cannot ignore what happens when their core is being threatened.

Theme 2: Follow, Lead, or Leapfrog

Financial services institutions can follow three strategic directions. It is proposed they choose all three directions.

1. 1. Follow. By participating in consortia, standards groups, or open source projects, financial institutions can reap the benefits of a collaborative approach to figure out where the blockchain can contribute. Some of these efforts might lead to lubricating inter-banking relationships, while others will expose members to usable technology and best practices that can be imported inside the organization.

2. 2. Lead. This pertains to leading a number of initiatives internally where you discover and implement where the blockchain can streamline various parts of your business. This is where internal capabilities need to be proactively built, either internally or with the help of external services providers.

3. 3. Leapfrog. This might be the most difficult phase to initiate, because it will focus on thinking outside of your business model boundaries and inside new innovation territory. There is a key outcome-related distinction between this direction and the previous ones: leapfrogging should generate new revenues in new areas (top line growth), whereas the two will more likely be oriented towards saving costs or streamlining operations.

Theme 3: Regulations, Regulations, & Regulations

The variety of financial services regulatory authorities around the world rivals the number of ice cream flavor varieties. More than 200 regulatory bodies exist in 150 countries, and many of them have been eyeing the blockchain and pondering regulatory updates pertaining to it.

Imagine if each one of these bodies issued their own type of blockchain regulations, without coordination, or without due consideration for the full implications of such policies. Not only would a mess ensue, but potentially the blockchain technology industry might get killed as a result of the resulting massive confusion.

The Commissioner of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), J. Christopher Giancarlo, underscored that specific point during a speech he made in March 2016 at a conference organized by The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (tdCC). He said:

“Yet, this investment faces the danger that when regulation does come, it will come from a dozen different directions with different restrictions stifling crucial technological development before it reaches fruition.”

When the Internet arrived, governments and policy makers were smart enough to not regulate it too early, and that contributed to its growth. The reality facing financial services institutions is, once again, they will be at the mercy of the regulators when it comes to the blockchain.

Banks are between a rock and a hard place: the blockchain is global, but regulations have forced them to focus on serving local needs. Regulation has protected them but it could also hurt them at the same time (if it does not evolve).

Theme 4: Legalizing Blockchain Transactions

At the heart of reaching widespread adoption for blockchain-based business interactions, transactions that are processed by a blockchain will need to be recognized as legally binding and acceptable within compliance requirements. This might involve revisiting recordkeeping or compliance rules, or at least ensuring that new regulation does not specifically prevent institutions from using the blockchain to run these transactions, or at least to allowing them to experiment with that technology to continue showcasing new capabilities, and learn where it can lead.

A skeptical question might be: If trust is the key blockchain enabler, banks already trust one another, so why do we need a “trust network”? The answer lies in the fact that when we examine the cost of running the current trust system, we will find these costs have become excessive. This is in part due to regulations, and in part due to the required complex integrations between the proprietary systems of each financial services institution. Add to that the indirect losses resulting from delays in settlement closures, and you endup with a high cost margin that is ripe for the shaving.

Theme 5: Do Banks Want a Better Inter-Banking Network?

Each bank has their own proprietary systems, and they are required to use private networks they either own or control in order to move money that is in their possession. It is a known fact that regulations and multi-party intermediary steps are principal reasons why inter-banking settlements take days to clear.

By virtue of its powerful vision of a single ledger, the blockchain is questioning if banks can continue depending on proprietary systems that are silos to one another. The prospects of a more homogeneous, but also more openly traversable audit trail of global transactions could offer unique insights and lower risks. In a correspondence, Juan Llanos, a certified AML and risk expert in FinTech and cryptography told me:

“Today’s AML paradigm is based on heavy customer due diligence and light (intra-company) transaction monitoring. Blockchain tech enables enhanced transactional analyses that were not possible before. In the pre-blockchain era, regulated financial institutions could only do intra-company transactional analysis, and had to share information via analog or documentary methods. Network-wide analytics that are possible with blockchains transcend industries and jurisdictional borders. There is now an opportunity to trade-off reduced KYC requirements (thus fomenting financial inclusion) for the increased behavioral transparency afforded by the blockchain.”

The key question becomes whether law enforcement authorities and regulators are able to embrace this paradigm shift. In the long term, a large part of compliance could move towards intelligence, because blockchain networks offer more transparency and analytical oversight.

Theme 6: Can the Banks Redefine Themselves or Will They Just Improve a Little?

Here is a summary of the dilemma. Banks do not want to change banking. Startups want to change banking. Blockchain wants to change the world.

Banks will need to decide if they see the blockchain as a series of Band-Aids, or if they are willing to find the new patches of opportunity. That is why I have been advocating that they should embrace (or buy) the new cryptocurrency exchanges, not because these enable Bitcoin trades, but because they are a new generation of financial networks that has figured out how to transfer assets, financial instruments, or digital assets swiftly and reliably, in essence circumventing the network towers and expense bridges that the current financial services industry relies upon.

KEY IDEAS FROM CHAPTER FOUR

1. We would be asking a lot if we asked financial services institutions to fully embrace the blockchain. In reality, what they will do initially is to pick and choose what they like and disregard what they do not like about it.

2. Although a global bank or exchange is not happening any time soon, the feelings and behaviors of a global bank are needed. The blockchain can help.

3. The Financial Services sector will need to stall new regulation while simultaneously updating the existing regulation to accommodate the innovation introduced by the blockchain.

4. The litmus test is to run transactions without a central clearinghouse in the middle. Verifying identity and validating counterparties can be done in a peer-to-peer manner on the blockchain, and that is the preferred method that organizations should be trying to perfect.

5. Strategic decisions await financial institutions, and they must have the courage to leapfrog, and not just advance to the next level playing field and be content with it.

NOTES

1. PayPal “Who we are,” https://www.paypal.com/webapps/mpp/about.2. The Pulse of FinTech, 2015 in Review, KPMG and CB Insights, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/03/the-pulse-of-fintech.pdf.3. “The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) provides a network that enables financial institutions worldwide to send and receive information about financial transactions in a secure, standardized and reliable environment.” (Source: Wikipedia) http://swift.com/.4. “Virtual Rivals,” The Economist, 2000, http://www.economist.com/node/348364.5. “My Financial Stack as a Millennial,” Sachin Rekhi, http://www.sachinrekhi.com/my-financial-stack-as-a-millennial.6. Update to the Global Landscape of Blockchain Companies in Financial Services, William Mougayar, http://startupmanagement.org/2015/12/08/update-to-the-global-landscape-of-blockchain-companies-in-financial-services/.7. “Blockchain 2015: Strategic Analysis in Financial Services,” William Mougayar,http://www.slideshare.net/wmougayar/blockchain-2015-analyzing-the-blockchain-in-financial-services.8. “Ethereum-inspired Clearmatics to save OTC markets from eternal darkness,” Ian Allison, IB Times, http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/ethereum-inspired-clearmatics-save-otc-markets-eternal-darkness-1545180.