Impossible to Ignore: Creating Memorable Content to Influence Decisions - Carmen Simon (2016)

Chapter 9. “I WRITE THIS SITTING IN THE KITCHEN SINK”

The Science of Retrieving Memories Through Stories

What were you wearing two days ago? Take two seconds to think about it before you continue reading.

If you tried to answer, your mind calculated quickly which day was “two days ago,” and from there it jumped to where you were (work, home, vacation), what you were doing (meeting with clients, spending time with family), and what other tangential thoughts, facts, and feelings were linked to that day. For instance, if you spent the day with someone you liked and you did something meaningful, some positive emotions came to mind, too. If the opposite happened, then negative emotions briefly became active. If these elements were easy to retrieve (visuals, actions, facts, meaning, and emotion), you found it easy to answer the question.

But maybe you found the question hard to answer, in which case there are several plausible reasons. One is interference, which means that too many memories in the same category are alike, and with enough repetition of similar stimuli, specifics turn into generics. For example, let’s say you work in a formal office most days, doing similar things each day, and your outfits consist of business casual clothes, which are not that easily distinguishable from one another. It is difficult to answer the question “What were you wearing two days ago?” with precision, but you could answer it with gist. A typical response I get is, “I was wearing pants and a shirt.”

We may also struggle with the question because there may be no deep or pragmatic meaning associated with what we were wearing two days ago. Someone may say, “Who cares?” The attitude changes if we had a job interview two days ago, or an important date, or an occasion where we wanted to impress someone. The meaning and, implicitly, the emotion attached to these visuals and actions serve as strong hooks to retrieve memories later.

Forgetting caused by interference or lack of meaning or emotion is not a problem when remembering attire. It becomes a problem when our audiences hear information from us that is not easily distinguishable from something they heard elsewhere. If someone were to ask our listeners “What content do you remember from two days ago?” they may not be able to remember because too many memories may compete with each other in the business content category. In the previous chapter, we learned how to be on people’s minds in a distinguishable way so they can retrieve memories easily and accurately. In this chapter, we expand on that topic further by answering the question “How do people retrieve memories?” If we share information at Point A and expect them to remember it at Point B, how will they search their memories and bring to mind something we consider important?

In many cases, to retrieve a memory, we mentally travel to a specific place and time and then search for images and actions that took place, much like we did with the outfit exercise earlier. While on this mental travel, we may also extract meaning and factual information about the world. See how these elements are reflected in actor Al Pacino’s interview in the book The Meaning of Life. Al Pacino remembers the first car he ever bought when he was in his early twenties, just as his movie career started blooming:

I went with my friend Charlie and got this white BMW right out of the dealership. We get in the car and drive to my apartment in Manhattan. As we’re driving, I’m thinking, “Y’know, this just isn’t me.” It just didn’t feel right. But I said to myself, “What the hell, you’ll get used to it.” I parked it in front of the apartment, and we went for a cup of coffee. When we came down to drive Charlie home, the car is gone. I remember looking at that space where the car used to be, looking at Charlie, and laughing.

Then Pacino has a flashback.

Years before, Charlie and I were riding bikes and we went into Katz’s Deli on Houston Street. Now, the relationship I had with my bike was much different from the one I had with the car. I’d had that bike for a couple of years and used it to get from the Bronx to Manhattan. I didn’t have money at the time, and it was not only my form of transportation but also a great source of fun and amusement. It was one of the few things I could do for free. Anyway, Charlie and I park our bikes on the street and go in the deli and get some hot dogs. Every other bite I would turn around to check on the bikes. I must have put mustard on the dog or something, because the next time I turn around, the bikes were gone. I remember running outside, and they were nowhere in sight. It wasn’t funny that time.

It is fairly easy for Al Pacino to retrieve these memories—and for us to retell his story to someone else—because the brain has encoded a lot of information in a way that comes naturally. Consider these narrative elements:

1. Sensory impressions in context. We “saw” things: car, bikes, deli—and not just any deli, Katz’s Deli—street, apartment, Bronx, Manhattan. We “tasted” coffee, hot dogs, and the mustard on those hot dogs.

2. Actions across a timeline. We visualized events happening in a sequence: getting into the car, driving, looking, parking bikes, laughing, and running.

3. Facts. We learned a few indisputable things, such as the existence of Katz’s Deli, a BMW dealership, and a route from the Bronx to Manhattan.

4. Abstract concepts. We learned ideas that can be dissociated from a time and place, such as ownership of a car or a bike, or a statement such as “It was one of the few things I could do for free.”

5. Meaning. We inferred conclusions we can use later on and in other circumstances: “Sometimes we feel more attachment to small things than big things” or “Things have relative value.”

6. Emotion. We felt excitement at driving a new car, confusion when the car is stolen, resignation afterward, anxiety parking the bikes, and a strong sense of loss when the bikes are gone.

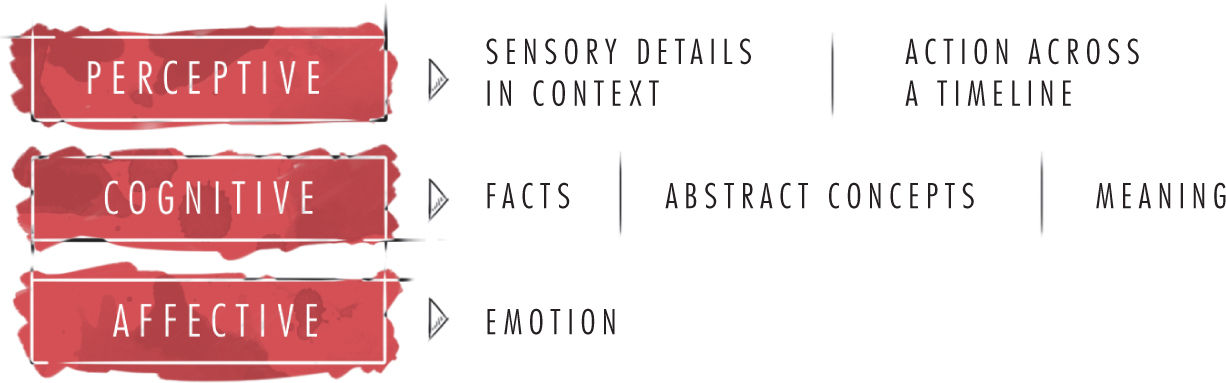

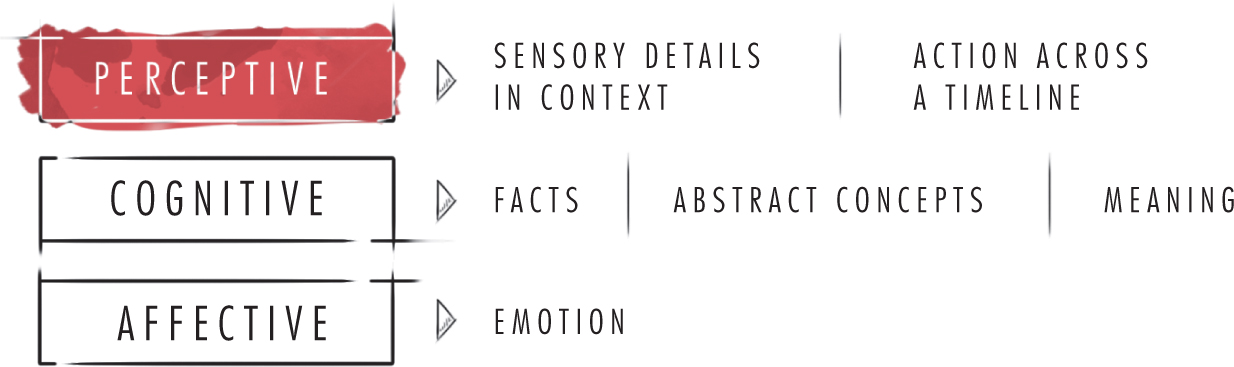

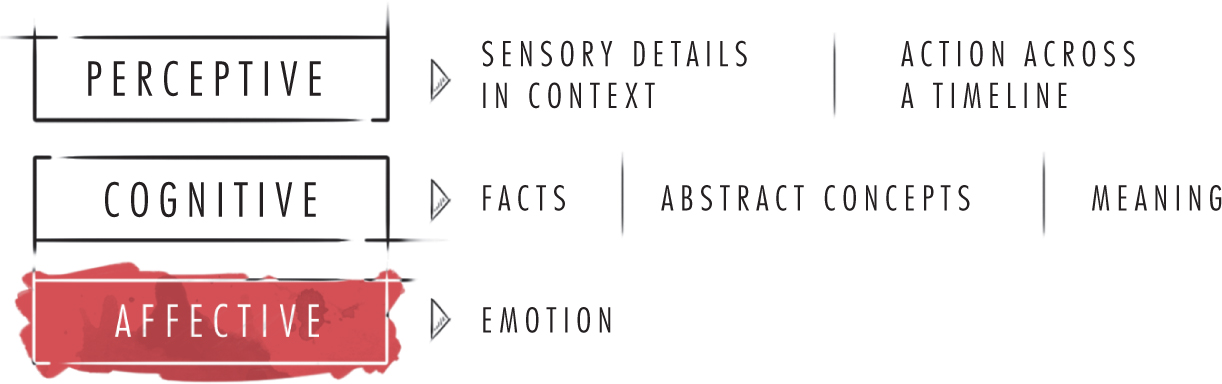

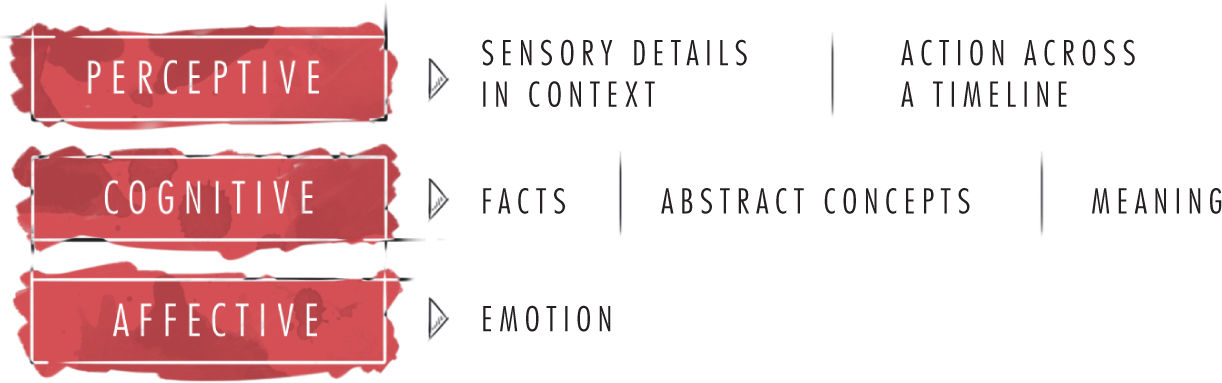

How many of these perceptive, cognitive, and affective elements are reflected in the content you share with others? It is an important question to answer because a combination of perceptive, cognitive, and affective elements is mandatory for encoding and retrieving memories. This combination is also important because it gives us a formula for storytelling.

MEMORABLE STORYTELLING

Considering this model, it is easy to see why well-crafted stories are remembered; a good story invokes more senses and activates more parts of the brain: visual cortex, motor cortex, frontal cortex, amygdala, to name a few. As a result, when we tell a story well—especially if we lived the event ourselves—we can help others encode more memory traces. From this angle, the adage “Less is more” in creating content is a myth. It is the combination of perceptive, cognitive, and affective elements and the elaboration on them that helps an audience build more memory traces and connections in their minds.

Even though by some standards the Al Pacino story may be considered long, the length pays off in extra encoding. In addition, with elaboration, we’re building more cues for retrieval. Seeing hot dogs, bikes, a deli, mustard—any of these later can trigger the memory of this story.

The absence or imbalance of perceptive, cognitive, and affective elements in a story is what makes it forgettable. Ineffective communicators tell stories that (1) stay too factual or too abstract (nothing wrong with facts or abstract ideas, but when the other components are missing, it leads to forgetting); (2) have no plot—nothing really happens across a timeline; and (3) lack emotional intensity.

Let’s identify practical ways in which we can combine perceptive, cognitive, and affective elements to create memorable stories and influence other people’s long-term memory.

BALANCE PERCEPTIVE AND COGNITIVE ELEMENTS

Learn the Difference Between “Abstract Versus Concrete” and “Generic Versus Specific”

When creating business content, we tend to stay more on the cognitive side (facts, abstract ideas, meaning—all of which are offered most frequently as words) than on the perceptive side (vivid visuals and actions). It is typical to hear statements such as “Our solutions drive the vital business process between the buyer’s interest in a purchase and the realization of revenue. With our software, companies increase sales effectiveness while maximizing visibility of …” What does a statement like this mean to you? Can you picture what the speaker said? Will you remember any of it in the next few days?

MEMORABLE STORYTELLING

It may be intuitive to believe that what is concrete and tangible, which appeals to our senses, is more memorable compared with abstract concepts, such as the ones in the statement above. The hot dogs and bikes we read about earlier may be more vivid in our minds than a “business process” or “maximizing visibility.” Vivid sensory details are definitely memorable, but abstract and factual concepts can be, too, provided they meet some conditions. Several guidelines about the importance of abstract concepts were included in the chapter on repeatable messages. Here we explore the topic in more depth and provide additional guidelines on how to make facts and abstracts memorable, since they are prevalent in business communication. First, let’s define two dichotomies: “abstract versus concrete” and “generic versus specific.”

Although these words are used interchangeably (concrete = specific; generic = abstract), there are differences between them. Something is concrete if we can perceive it with our senses. Swiveling chairs, lavender, misty air, cherry pie, and text message tones on a smartphone—all of these ignite various senses. If we can’t perceive something with our senses, we are talking about an idea or a concept that is abstract (it appeals to our cognition). Autonomy, courage, and cynicism are examples of abstract concepts.

While abstract and concrete are opposites, generic and specific are subsets of each other, with generic being a large group and specific representing an individual item of that group. In Al Pacino’s story, we did not read about a generic car (and possibly create only one memory trace); we read about a “white BMW right out of the dealership” (and could create multiple memory traces). Consider the difference between “he hit me” ↵ “he decked me” ↵ “he Steven Seagal’ed my butt.” The more specific we are, the more memories we encode in our audiences’ brains. Creative writing courses are a great way to learn how to produce deeper levels of specificity to impact our audience’s memory.

Notice the mixture of abstract-generic and specific-concrete in the article “What I Learned from the Worst Guy I Ever Dated” by Genevieve Field, who quotes from readers’ contributions. Lizzie, age 35, writes: “I met Bob when I was 22, and fell hard. He was a macho, messed-up guy: He ate raw eggs. He shot himself in the thigh with steroids. He drank Bud Light while lifting weights and wore his hat backward. But when two broken people get together, it’s not a resurrection of Jerry Maguire—no one completes anyone. You both just tear each other apart in new and awful ways.” The abstract ending is welcome after a series of concrete and specific sentences. If the specific examples went on, it would have felt like a dull list of facts. Lizzie’s submission was titled “We Seek the Love We Think We Deserve,” which is an abstract concept that represents an array of concrete thoughts.

There is a paradox regarding specific-generic and concrete-abstract and their impact on memory. We live every day in specific and concrete terms, but we tend to remember the generic and abstract, especially without reexposure or reflection.

Why is it sometimes easier to remember the generic and abstract? One interpretation is that these concepts are more interconnected, more networked, therefore increasing our chances for later retrieval. Another is that when we store items at a generic or abstract level, we can use them to interpret new events and plan for future action. We also tend to access these types of memories more frequently. And they take less mental effort to retrieve than the specific or concrete.

However, for our audiences to remember an abstract idea, we must still offer the specifics to help them encode information. The brain also needs to retain some of the original observational data to better adapt or reinforce generalizations or abstract concepts. Compare these two mission statements from organizations aiming to rebuild struggling communities in some urban areas. Which one may still be on your mind a few days from now?

“In the spirit of volunteerism and community partnership, we aim to improve homes and neighborhoods so that people can live in warmth, safety, and comfort. We approach our mission with the understanding that home ownership is an important factor in the stabilization and preservation of neighborhoods.”

“We will build 150 affordable, green, storm-resistant homes for families living in the Lower 9th Ward.”

The second message is the mission statement of the foundation established by Brad Pitt to help the displaced after Hurricane Katrina. To date, the foundation has completed 75 homes. A few days from now, we may not remember these exact numbers, but our initial exposure to them gives us a strong feeling of confidence, connection, and trust because of the specificity. If the second mission statement were merged with the first, we would have an even stronger package: specifics that draw us in and provoke an emotional reaction and abstract concepts we can retain for later use.

In business, too many content creators operate from one of two extremes. At one extreme, content is too abstract or generic, such as the statement earlier about “business process” and “maximizing visibility.” At the other extreme, content is too specific: “Data Protection Manager (DPM) is a backup and recovery solution. DPM provides out-of-the-box protection for Files and Folders, Exchange Server, SQL Server, Virtual Machine Manager, SharePoint, Hyper-V, and client computers. For large-scale deployments, DPM also allows you to monitor your backups through a central console or remotely.”

Why do we go to either extreme? The pull toward the abstract happens because we tend to speak in conclusions, rather than showing how we reached those conclusions. This is because we don’t want to think about the details, we don’t want to waste people’s time with details, or we don’t know the details. Here is an example.

Consider these statements: “Sometimes people drive as fast as they can, with the attitude that as taxpayers, they own the road.” “People often cut in line.” “Sometimes people feel underpaid and help themselves to a few ‘souvenirs’ from work to offset lower wages.” “Clerks at the post office get snappy when you don’t fill out the right forms.” You may think these specific statements, but you don’t say them. You simply say, “Everyone is so cranky these days,” which is your conclusion. Notice how many sensory details the conclusion is missing.

The pull toward the specific is often driven by ego and the desire to make an impression. People want to show off their brilliance. During a brain science workshop with executives, I remember one man who said, “If I did not include all those details in my presentation, my boss would think I am lazy.”

Neither extreme (content that is too perception-based or too cognitive-based) is favorable for memory. Too much of either is boring after a while because it becomes repetitive and predictable. Consider a balanced ratio of abstract-generic and specific-concrete. Here are two examples:

“She wasn’t doing a thing that I could see, except standing there, leaning on the balcony railing, holding the universe together.” (J. D. Salinger, A Girl I Knew)

“I met in the street a very poor young man who was in love. His hat was old, his coat worn, his cloak was out at the elbows, the water passed through his shoes, and the stars through his soul.” (Victor Hugo, Les Misérables)

To make sure we don’t err on either side of the spectrum, when our content becomes too abstract, we can ask, “Can I give an example of this?” “Can I include some facts?” Then, when the content is too concrete and specific, we can ask, “What is the bigger picture?” or “What is an idea that people can apply to other situations beyond this context?” The brain is constantly on fast-forward, and it will appreciate portable messages.

Here is a business example of the proper balance between the abstract and generic and the specific and concrete. This was the mission statement of the snowboard equipment company Burton at a time when snowboarding was a small niche and skiers considered it annoying. Jake Burton wanted to prove them wrong. The company’s poetic vision comes from the rhythm between the abstract and concrete and the generic and specific. No PowerPoint slides are necessary when you achieve this type of balance.

We stand sideways.

We sleep on floors in cramped hotel rooms.

We get up early and go to sleep late.

We’ve been mocked.

We’ve been turned away from resorts that won’t have us.

We are relentless.

We dream it, we make it, we break it, we fix it.

We create.

We destroy.

We wreck ourselves day in and day out and yet we stomp that one trick or find that one line that keeps us coming back.

We progress.

Burton’s statement contains concrete words that appeal to our perception: “stand,” “get up early,” “sleep late,” “floors,” “resorts,” “stomp.” It also contains abstracts: “relentless,” “create,” “destroy,” “mocked,” “trick,” “line,” “progress.” We also see generic words: “make it,” “break it,” “fix it,” “day in and day out.” And these are paired with some specifics. We don’t just see hotel rooms; we see people sleeping on “floors in cramped hotel rooms.”

When analyzing the content you’re creating, ask yourself: What is the ratio between perceptual and cognitive elements? Is your language concrete and specific enough to cause a reaction, but abstract and generic enough to allow the audience to derive meaning that is easy to remember and use later in many other contexts?

Zoom In on Details Based on Your Audience’s Expertise

Determining the ratio between perceptive and cognitive also depends on whether you’re addressing experts or neophytes. Beginners tend to prefer the more specific and concrete, so for this type of audience, amplify the perceptive elements. More sophisticated listeners tolerate a higher level of the abstract and generic because they have more developed schemas for the content you’re sharing. For this type of audience, amplify the cognitive side.

Here is an example of the ratio of details different people need as they listen to experts. The SR-71 was a famous U.S. spy plane, considered to be the world’s fastest jet. The plane could go from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in 64 minutes, averaging 2,100 mph. Fewer than 500 pilots had the chance to fly it. When I asked Bert Garrison, a former SR-71 pilot, what he remembered about flying that plane, he mentioned a comment he heard repeatedly from his peers: “If you ever look out of the window, she will bite you in the ass.”

This was an abstract conclusion. If you share just this conclusion with other pilots, regardless of what aircraft they fly, it’s likely they will understand what that abstract sentence means, and you can move on with the conversation. Novices would need specifics to appreciate and understand the conclusion. An SR-71 pilot was a very busy pilot. What kept him so busy? “You’re burning fuel at a high rate, 45,000 pounds per hour at Mach 3,” Garrison explained, “so you have to manage your fuel balance. You’re making sure the center of gravity of the airplane is staying in trim. You’re maintaining the inlets so they are running efficiently and you’re burning the least amount of gas. You’re constantly checking the altitude to see if the fuel flow was correct for that altitude, and if it wasn’t, you would have to climb.” It is these details that will keep neophytes interested in the conversation and enable them to understand the meaning of the abstract statement.

Regardless of the audience expertise level, it is practical to lead with the pattern your audience expects and deviate from that sequence to break the pattern: {perceptual, perceptual, perceptual, cognitive} or {cognitive, cognitive, cognitive, perceptual}. With this approach, we avoid boredom, and we feed the brain’s constant aim to mitigate two processes: generalization and specialization. This dual process is how the brain thinks.

Pictures Versus Text: Which Is More Memorable?

We’ve discussed the importance of balancing perceptive and cognitive details, focusing mainly on verbal information. Since many business communicators err on the side of cognitive details (facts, abstract ideas, and meanings), let’s find ways to include perceptive elements in our content, using visuals and actions. After all, sensory information is at the basis of our memory.

Do we remember pictures more than text? Intuitively, people believe that pictures are more memorable, but let’s investigate more deeply to see if this is always so. The analysis matters because it is not always easy to create sophisticated visuals to include in our communication materials; or if we do have the budget to create amazing visuals, under some conditions, they may still be forgettable. Words and numbers are often easier and cheaper to produce, but they have some conditions for recall.

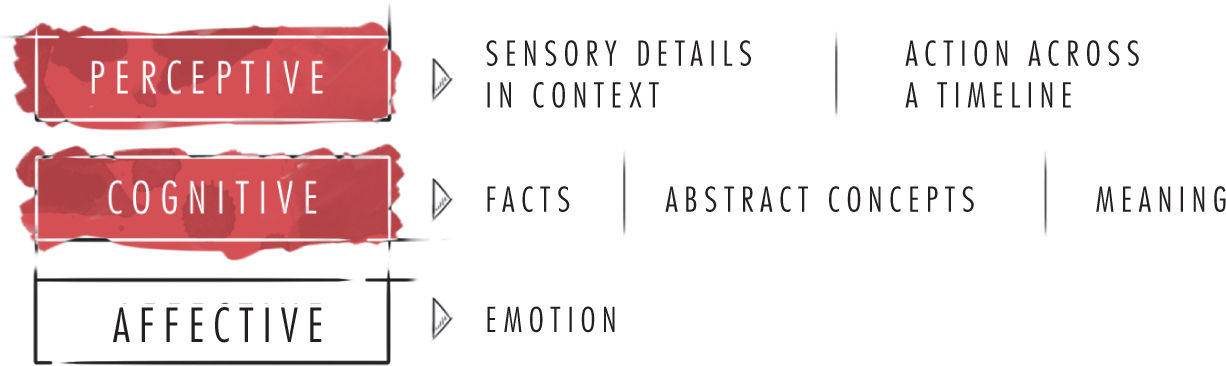

Visuals seem to win memory space because we have a reflexive preference for them. We are visual beings: we take the world in mainly through visual receptors. Pictures are often more enjoyable and help us arrive at meaning more quickly. They also tend to provoke stronger emotions and provide a context. Which one would you be more likely to remember in a few days: the text or the image?

PICTURES ARE OFTEN MORE MEMORABLE THAN TEXT BECAUSE THEY ARE GENERALLY MORE INTERESTING

Many businesses capitalize on the human propensity toward visuals, which is why the Facebook timeline is appealing and why Pinterest and Instagram are insanely popular. It is also why data visualization businesses have been booming: who wants to spend hours looking at Excel spreadsheets instead of pretty charts that indicate trends and may lead to insights?

Processing visuals is often more efficient than processing text, especially when text is in a number format. In Brain Bugs, author Dean Buonomano says, “We can find a face in a crowd faster than we can come up with the answer to 8 × 7.” He adds, “We have an inherent sense of the quantities 1 through 3, but beyond that things get hazy. We may be able to tell at a glance whether Homer Simpson has two or three strands of hair but you will probably have to count to find out whether he has four or five fingers.”

Image processing efficiency means that a picture enables us to absorb a large amount of information quickly, hence the adage “A picture is worth 1,000 words.” From a memory perspective, let’s place this maxim under scrutiny. Two scientists from the University of North Carolina recently noted, “A picture is worth 1.5 words to be exact.” They discovered that while simple line drawings resulted in superior recall compared with the printed word, this advantage disappeared when the words were spoken.

This suggests that there may be another way we can ask the question about memory for images versus memory for text: In what situations are pictures not superior? Surely there are circumstances for text supremacy. If someone asked us to picture the rainbow, we could do it effortlessly. If we were asked to name the colors in the right order, we would struggle … unless we remembered the mnemonic device we learned if we attended an English-speaking school: ROY G BIV.

When comparing the impact of words versus images on memory, cognitive scientists have offered a theory called dual coding: when we look at visuals or text, we have the opportunity to encode them twice, via a visual code and a verbal code. If we see a picture of a banana, it is easy to encode it twice: a code for the visual we see and a verbal code we generate quickly because the picture is easy to label. This is advantageous because generating two memory traces (dual coding) increases the likelihood of retrieval. The same holds if we see the text “banana.” We can still encode it twice: the verbal code we see and its visual correspondent, which is easy to create because the item is easy to picture.

In studies where people are asked to generate a mental picture when they read words, findings suggest that subjects remember those words as accurately as if they were shown pictures.

A picture is memorable when it is easy to label, and text is memorable when it is easy to picture.

Text and graphics have the potential to be equals in memory. What this means to our content creation is that we don’t have to create or buy a picture for everything we share. We can still impact others’ memory with text, as long as the text generates a mental picture and this picture is easy to form. For example, “I write this sitting in the kitchen sink” is the first line in Dodie Smith’s novel I Capture the Castle. She continues, “That is, my feet are in it; the rest of me is on the draining board, which I have padded with our dog’s blanket and the tea cosy. I can’t say that I am really comfortable, and there is a depressing smell of carbolic soap, but this is the only part of the kitchen where there is any daylight left.” The words are strong enough to generate dual memory traces. We don’t need actual photographs to see her context.

When we don’t have enough time to generate a label for a picture, visuals lose the dual coding advantage. In a study where participants viewed approximately five items per second (text and visuals), people did not remember pictures more than words. Scientists suspect it is more time consuming to come up with a label for a picture than to read words.

Based on the evidence so far, we can infer it is possible for some text to be memorable and for pictures to be forgotten. Ultimately, images and text are both graphical elements. Each comes with its own set of conditions for impacting memory. Artist Bert Dodson offers a strong metaphor to use words and pictures for maximum memory impact. He asks us to imagine two ladders, one labeled “Words” and one labeled “Pictures.” You start climbing one of them until at some point, he says, “the climbing gets difficult.” Dodson advises that instead of getting stuck, “You simply cross over to the other ladder. Suddenly the climbing gets easy again.” So it’s not one or the other; it’s moving from one to the other. In the case of Dodie Smith’s novel, after she builds a mental picture of writing from the kitchen sink, she switches to something more abstract: “… I have found that sitting in a place where you have never sat before can be inspiring…”

Pictures don’t always have a memory advantage. We often place text at a disadvantage, which is why it is easily forgotten. In the next few pages, let’s answer the questions “What makes text memorable?” and “How do we avoid forgettable pictures?” The answers will help us improve storytelling and enhance memory.

Link Abstract Words to Concrete Pictures

Business content tends to contain more abstract than concrete or specific words. We hear messages such as “Corporations realize that they must provide differentiation through higher-value experiences, cost efficiency, and agility. These ultimately lead to other higher goals, such as leveraging of core assets, revenue generation, and brand loyalty.” Notice all the abstract words: “differentiation,” “value,” “efficiency,” “agility,” and “loyalty.” Also notice the generic (and still abstract) words: “experiences,” “assets,” and “goals.” There is nothing wrong with this type of message as long as listeners extract the same meaning from the statement as intended by the speaker. When content is abstract, it is important to ask: Do the abstract concepts mean the same to you as they do to your audiences?

Different people have different images of abstract words, depending on various contexts, life experiences, beliefs, and current intentions. Take the word “value,” for instance. If you’re an accountant, you may understand it as the monetary worth of a specific good or service. If you’re an economist, you may see it as the benefits and rights of ownership, such as utility or the possibility to exchange those goods or services for something else. If you’re in marketing, you may consider the perceptive value of a good or service and whether people are willing to pay for it because it meets a need. If you’re a mathematician, value is simply a quantity represented by a number.

When we communicate in abstract concepts and leave it to an audience to come up with a mental picture for what we said, we run into a couple of problems:

1. People may find it hard to imagine some abstractions and give up. For instance, how do you visualize these words: “Our virtualization products deliver a complete and optimized solution for your entire computing environment”? Unless you work in cloud computing, it is difficult to picture much. Your audience is likely to zone you out and focus on other stimuli that take less cognitive effort.

2. When people don’t understand what we mean, we have to speak to them multiple times, which is ineffective. And what happens if we don’t have the opportunity to clarify our message multiple times?

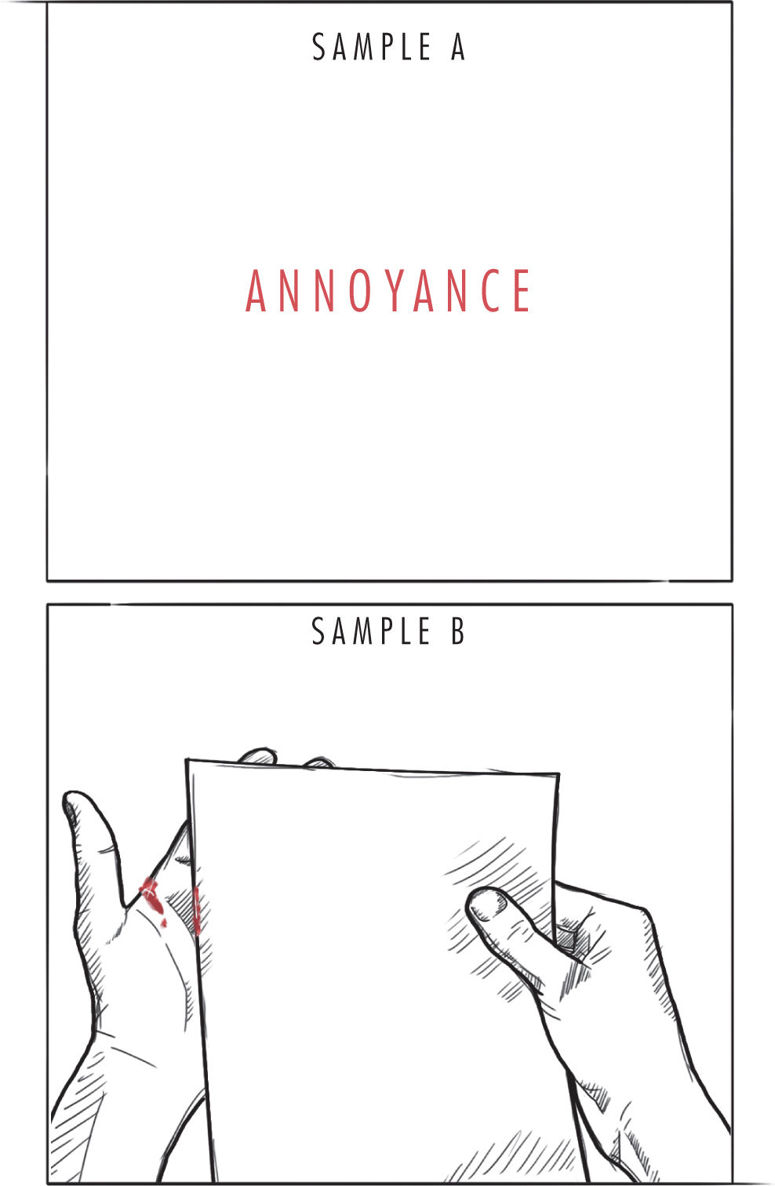

One way to ensure that others extract the same meaning we do about a concept is to pair abstract words with concrete pictures. Check out the pictures that follow related to the abstract concept of “socializing.” The mental picture someone has in mind may be different from someone else’s, which is fine, but if we picked one or the other, at least an audience knows what we mean by “socializing” in more specific and concrete terms.

The advantage of combining abstract words with concrete pictures to control for meaning is that our visual system is able to extract conceptual information from a visual stimulus three or four times a second. In an MIT study, researchers found that the minimum time needed for visual comprehension is 13 milliseconds. That’s fast. And it is possible because we have perfected our visual system throughout our lifetime to categorize pictures and scenes after one visual pass. Mary Potter, MIT researcher, concludes, “The fact that you can do that at these high speeds indicates to us that what vision does is find concepts … that’s what the brain is doing all day long … trying to understand what we’re looking at …” Pairing abstract words with concrete images gives us the advantage of controlling for meaning in a quick and efficient way.

SOCIALIZING

DO YOU AND YOUR AUDIENCE HAVE THE SAME PICTURE OF AN ABSTRACT CONCEPT?

Another advantage to linking abstract words with images is that when we process images, we store not only the meaning of the picture but also visual details, such as color, size, shape, and texture, which means we help others form multiple memory traces, increasing the likelihood of retrieval.

Often communicators use visual metaphors to link abstract concepts to something concrete or specific, especially in an effort to make complexity easier to understand. Imagine something complex, such as an aircraft. Remember Bert Garrison, the SR-71 pilot? He also flew the B-52, which is a long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. He remembers a metaphor he was taught, which changed his flying style forever. “I was flying kind of rough, and one of my first aircraft commanders said to ‘fly like you’re chauffeuring people holding champagne glasses.’” It is a metaphor that he’s retained for decades. The commander could have said, “Fly it in a steadier way,” or “Ease up a bit.” When we use visual language and place concrete images in people’s minds, we have better chances at creating stronger memories.

Why metaphors have such a strong effect is a matter of debate. Marketing scholar Martin Reimann of the University of Arizona maintains that metaphors are rooted in our subconscious: they help us interpret our surroundings as we age; in other words, metaphors help us convert abstract environments or situations into more relevant terms. “We, as humans, try to understand the world, in part, by metaphors,” Reimann says.

Use metaphors to explain complex and abstract ideas, not simple ones. I saw someone recently use an image of a lion and its pride to explain the concept of being a supervisor. We don’t need a metaphor to understand that. Supervising has a clear meaning, and that meaning is fairly consistent among listeners. With the increasing popularity of stock photography websites, too many content creators use metaphorical images too often, rendering communication unnecessarily trite. Pictures of business professionals on a racetrack, attractive people in staged group encounters, or a dart in the bull’s-eye of a target are not additive to memory, especially when they are paired with simple concepts that are easy to understand. Metaphors linked to football, golf, sports cars, and mountaineering are often overused and may be too clichéd to still have impact.

Let’s say you have a complex concept you want to explain using a metaphor. There are two ways to go about it. One technique is to use an old metaphor but add a fresh meaning. For example, imagine someone speaking about tennis player Serena Williams not in a sports-related way, but rather focusing on her entrepreneurial skills.

Or create new metaphors. Any book on creativity will steer our brains away from habitual metaphors. In SoulPancake, author Rainn Wilson offers a good list of sources of inspiration to move away from the cliché. “Go to a costume store,” he advocates. “Look inside a grand piano. Watch a pastry chef decorate a cake. Watch a bartender mix drinks. Watch a salsa lesson.” Any of these experiences—and many more you have the courage to explore based on your own interests and comfort level—can help you create new metaphors for abstract content. Make the first place you reach for metaphors your own experiences before going outside your world and borrowing from others’ stories.

The advantage of pairing abstract concepts with concrete pictures is that we are better able to control the meaning people take away from our communication. Burton, the company whose mission statement we read earlier, ends it with “Burton Snowboards is a rider-driven company, solely dedicated to creating the best snowboarding equipment on the planet.” The company wanted us to enjoy the original poetics but did not want us to lose sight of its meaning.

When referring to concrete elements (even when some are generic), their meaning stays fairly unchanged. For example, the meaning of a chair (a concrete and fairly generic object) is the same when we are 10, 20, 40, or 80 years old. Whether we talk about the generic category of chairs or we get specific, such as “a walnut and ebony rocking chair, handmade by renowned craftsman Sam Maloof, that sold for $80,500,” we can rely on the fact that most people will retrieve the same meaning. The way we value a chair may change: we may need it more when we are older, or we may not appreciate one selling for a high price. However, we understand the concept of a chair in a fairly consistent way. In contrast, the meaning of abstract concepts tends to change over time, from context to context, and from person to person. Hope at the age of 4 and hope at the age of 40 do not hold the same meaning.

When others extract a different meaning from what we intend, they may act in ways that do not serve us. When we control meaning, we are more likely to impact subsequent action. The easiest negotiations are the ones in which everyone in the room shares the same picture that means the same thing.

Wrap Abstract Words in a Concrete Context

Which will you remember better in this image: the picture of the Santa Ana winds or author Raymond Chandler’s text description?

DESERT WIND

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight.

Even numbers are memorable when they are presented in a concrete context. I am sure we can remember numbers that are linked to our cholesterol level, a new lover’s address, the completion time of a race, or a quota achieved at the last minute. It is possible for people to hate math but to love numbers.

The impact of context on memory has been demonstrated since the 1970s, when psychologists D. R. Godden and A. D. Baddeley designed a classic experiment in which divers learned a list of words under water and were later tested on dry land. The experiment showed reduced recall when the context changed and the initial environment was not reinstated. Scientists have extended the notion of context from environmental factors to the mood we’re in at the time we learn new information or to the time at which we learn it.

More recently, in an EEG study, participants were shown a series of pictures (e.g., dog, tree, car) and asked to identify whether the picture displayed an animate object, whether the object could be used indoors, and if it could fit in a shoebox. Half of the 42 pictures required a positive response. Some participants saw pictures only once and some three times. In the repetitive condition, researchers also varied whether people saw the pictures multiple times in the same context or in multiple contexts. When their memory was tested, participants were shown old pictures along with new pictures and asked to recognize the ones they had seen before. The obvious finding was that people showed more accurate and faster recognition for items that had been presented three times, not just once, and this recognition was based on recollection (memory for details). However, people also showed a greater degree of familiarity for items that had been seen in multiple contexts. The study also confirmed that deep encoding (e.g., asking participants to comment on animacy, size, and usage) also increased recollection.

Repeated exposure to the same information in the same context leads to item-context binding, which supports verbatim information (recollection). But in real life, things aren’t so simple. We encounter events in multiple contexts. In this situation, we must ask: Do we want people to recollect things precisely, or will simple familiarity be sufficient for their next move in your favor? If we want precision, it helps to present the same information in the same context repeatedly. If familiarity is sufficient, varying the context is better.

When creating content, it is also practical to ask: Will this context be replicated later to offer cues to retrieve memories? For example, have you visited your old high school as an adult? You may have thought that you had forgotten a lot, but being there brings a flood of memories that are activated by simply revisiting the context. What context will your audiences be in when you expect them to remember certain things? And do you want them to remember verbatim information (rely on recollection), or will gist memory do (rely on familiarity)?

Recently I was working on a presentation for Lyra, a company that helps enterprises manage their behavioral healthcare. The purpose of the presentation was to show how data-driven technology enables corporations to approach behavioral health in a way that improves productivity and reduces costs. In one segment, we were making the point that data-driven technology helps users find mental healthcare with precision. To visualize this, we showed a map of an area in San Francisco and simulated a search engine in which someone typed various terms: “psychological care in San Francisco, CA,” “medication management,” “experts in high-quality depression care,” “accepting new patients and in my network,” “near my office.” With each of these searches, icons disappeared on the map to represent the idea of eliminating unnecessary hits. When the presenter delivered the speech to an audience in Richmond, Washington, we switched the maps so that listeners could relate to the context better and seeing the map later would act as a cue for memory.

EMBRACE THE PERCEPTIVE

MEMORABLE STORYTELLING

Create a Symphony of the Senses

Earlier, we discussed the notion that a memorable story has the presence and proper proportions of perceptive, cognitive, and affective components. Most business communicators feel comfortable elaborating on the cognitive, presenting facts, abstract concepts, and meanings. It is a safe technique that makes them feel like they are bringing value with metrics, charts, and graphs.

There are two drawbacks to focusing mainly on facts, abstract concepts, and meanings. The first is that memories will be weaker. It is difficult for our audiences to remember many facts, unless we repeat them regularly, and repetition is often hard in business contexts. Sometimes we have only one chance to leave a mark. The second drawback is that when we present facts, abstract ideas, and meanings—essentially conclusions—it is difficult to control those conclusions. People are more inclined to act if they believe they reached a conclusion. And it’s harder to reach a conclusion when they don’t see what you saw. This is why we need sensory details in our content.

A good example with abundant sensory details placed in context comes from speaker and author John Vaillant’s TED talk about what humans and tigers have in common. He relates his studies of tiger attacks in the Russian Far East, which he describes as a “rough and remote place, bordering North Korea and China, where temperatures drop to -40F,” adding that “it rains a lot in the summer, the bugs are brutal …” In 2007, when he started his studies, he noted the story of one man who shot and wounded a full-grown male Siberian tiger. “These are big animals,” Vaillant observes. “They can weigh 500-600 pounds, they can jump across this stage … and have been known to eat the Russian equivalent of grizzly bears.” He continues, saying the tiger went to his enemy’s cabin, found the belongings that had his scent on them, and “chewed them to pieces.” The tiger waited by the cabin until his shooter came home and killed him by his front door.

After talking to the villagers, Vaillant found that this attack was an exception. Humans and tigers have many commonalities: both species are adaptable, apex predators with good memories, a capacity for vengeance, and the ability to problem-solve. The rest of his speech focuses on lessons that tigers can teach us about long-term success and mutual survival, including sustainability. His speech has influential power because we are better persuaded when we can reach a conclusion on our own, and we can do that more easily when given sensory details of an experience. Vaillant manages to sustain attention for his 20-minute TED talk with abundant details that appeal to all our senses. I saw his TED video years ago, and some of the visual details are still on my mind.

One of the best and easiest ways to include perceptive details and activate our audiences’ senses is to share personal experiences.

Kevin Kregel was a NASA astronaut from 1990 to 2003. I had the opportunity to speak with him, and no interview with an astronaut is complete without a story about seeing our planet from an exclusive vantage point. Here is what Kregel remembers from one of his missions, after being in space for eight days: “The flight deck on the space shuttle is not that much bigger than a 737. A bit wider, a bit deeper, but not by much. There are six windows and two overhead windows. We turned off all the displays on the flight deck and blocked off the access to the mid-deck because there are lights there that cannot be shut off. It was pitch black. Even though there was not much room, we all had good body control, and floated, and put our faces in front of a window so you could not see anybody else. You could see the Earth below, and the stars, and we floated that way for 45 minutes, listening to Pink Floyd, The Dark Side of the Moon. It felt like you were just flying and you weren’t really in the shuttle. Nobody said a word. Nobody moved. Nobody touched anything. We were all floating in our separate window and the sun finally came up, and it was gorgeous.” He concluded humbly, “I guess that’s what it must have been like to be on LSD in the’60s.”

Personal stories influence others’ memory not only because of the abundant sensory details and actions across a timeline, but also because (1) they are easier for you to remember, so you’re more likely to share those sensory details, and (2) you have the backstory, which may provide additional sensory details. If people have questions, you will find them easier to answer. If anyone asks you details about the Al Pacino story earlier, you won’t know unless you’re Al Pacino. If anyone asks you details about what it’s like to write from the kitchen sink, you won’t know unless you’re Dodie Smith. Or … unless you dare try it yourself. What if you created your next pitch with your feet in the kitchen sink?

AVOID FORGETTABLE PICTURES

Pictures have the ability to ignite the senses, but not all pictures impact memory equally. Here are some ways to avoid forgettable visuals.

Escape the Cliché

Despite their physical distinctiveness compared with text, it is still possible to forget images because they are dull. Check any stock photo site that offers pictures of business professionals in awkward contexts, such as doing yoga, holding megaphones, or using laptops on mountaintops and wheat fields. Sometimes communicators are in such a rush that they don’t bother to purchase the images, and we still see the copyright holder’s watermark in the corner of the photo or even right in the middle. Many media outlets such as BuzzFeed, Mental Floss, Reddit, The Hairpin, or the Huffington Post beautifully capture the ridiculousness of some stock photos. A 2011 article on The Hairpin website, titled “Women Laughing Alone with Salad,” went viral and captured attention for months.

Why do people use clichés? To answer, we look at variables that tend to block our creative thinking, which include stress, time constraints, worries, fears, unsolved problems, and other peoples’ opinions. Some content creators also tend to be lazy observers. Who has the time to look for an unusual reflection, the light hitting the floor just the right way, or an object seen from a different angle? We are too busy to notice the authentic around us because we focus on more pragmatic concerns, such as another meeting that day or the next e-mail. The more distracted we are, the more shallow our reflections, and the more trivial and clichéd our content. When we slow down and focus, we are able to improve our content.

It is hard to find memorable pictures on stock photography sites. It is easier to create memorable photos when we are in our neighborhoods, at work, or while traveling. We can find them looking at real people. Henri Cartier-Bresson, the master of candid photography, reminds us that we just “have to live and life will give you pictures.”

Use Vivid Images

Why does looking at vivid images help us remember? And what does “vivid” really mean? Neuroscientific studies confirm that the amygdala is more active when looking at images that are rated as vivid. Given that the amygdala plays a critical role in memory formation, it helps us to learn how to create vivid pictures.

One dimension of vividness is emotion. Rebecca Todd, a researcher in the cognitive science department at the University of British Columbia, has completed several studies on the concept of “emotionally enhanced vividness.” Using MRI scans, Todd and her colleagues have observed that how vividly we perceive something “predicts how vividly we will remember it later on.” When we look at images we consider vivid, we augment activity in the visual cortex and in the posterior insula, the part of the brain that integrates bodily sensations. Todd says, “The experience of more vivid perception of emotionally important images seems to come from a combination of enhanced seeing and gut feeling driven by amygdala calculations of how emotionally arousing an event is.”

In several experiments, Todd and her colleagues asked participants to look at pictures that were neutral or pictures that were emotionally arousing in positive and negative ways. The researchers then superimposed a level of noise on these pictures, much like the dots we used to see on old TV channels. Participants were asked to evaluate whether each picture had more, less, or the same amount of noise compared with the original. Participants considered the emotionally enhanced pictures—both negative and positive—to show less noise than the benchmark. When their memory was tested 45 minutes afterward and also one week later, participants showed improved memory for vivid pictures. The measure of vividness was based on how much detail participants used to describe the pictures they remembered. “Both studies found that pictures rated higher in emotionally enhanced vividness were remembered better,” Todd remarks.

Using brain imaging, she discovered that the amygdala, visual cortex, and interoceptive cortex activity increased the more vividness was perceived. “We know now why people perceive emotional events so vividly—and thus how vividly they will remember them—and what regions of the brain are involved,” Todd says.

Besides emotion, are there any other variables that make information more vivid? We can find a more detailed answer when we investigate how memory champions perform feats of memory, such as memorizing strings of more than 1,000 randomized digits or several decks of cards. When interviewed, these mental athletes confess they convert abstract information such as numbers or names and faces into vivid visuals with one or several of these attributes: funny, unreal, offensive, unusual, ridiculous, and definitely captured in motion. For example, the number 476 may be an image of Howard Stern bouncing on a barrel of grapes.

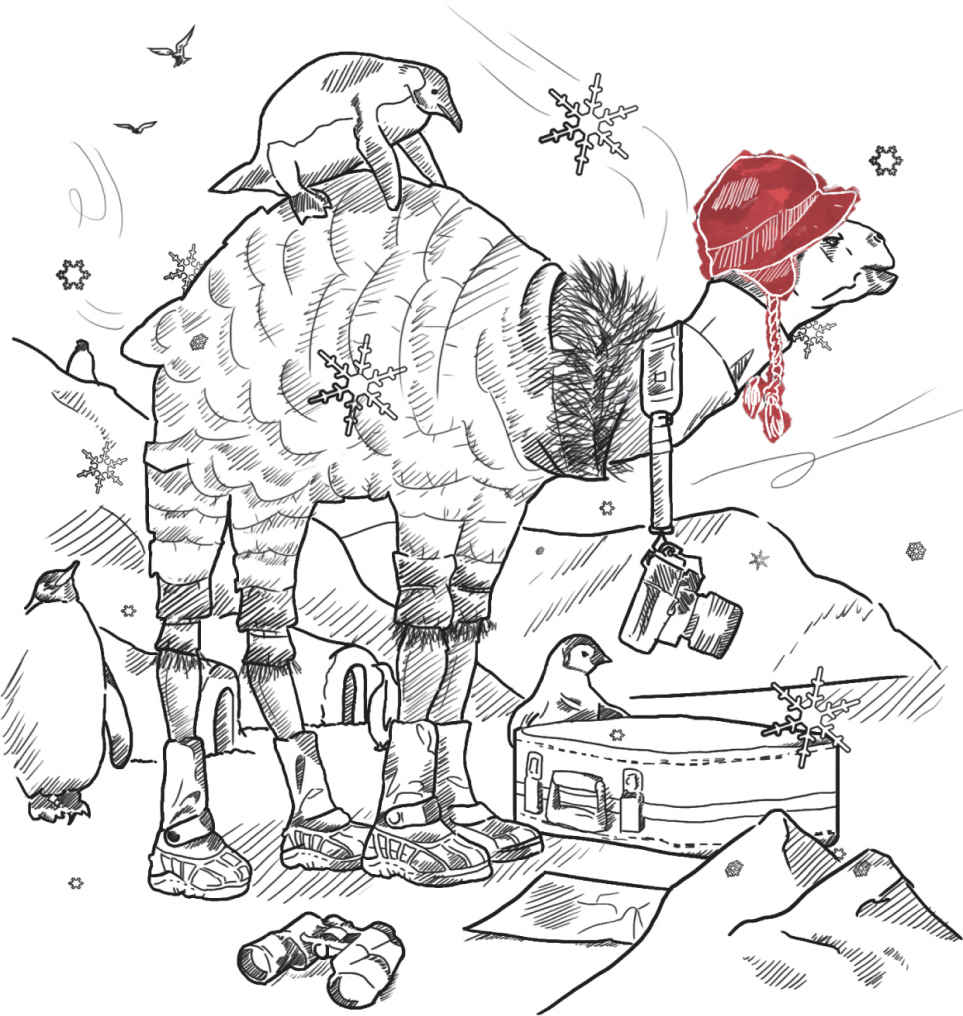

Vividness means adding an extra layer of tension, drama, or mystery that intensifies an emotion in our listeners. In earlier chapters, we defined emotion as a state elicited by obtaining a reward or avoiding a punishment. If we know what the reward is, we have more chances of intensifying a stimulus. For example, a few years ago, my friend and graphic artist Mark Damiano created a picture of a camel. If we were to see the camel in the desert, in its natural habitat, it might not make that much of an impression. A camel dressed up in an outfit is less expected. A camel in a winter outfit visiting the Antarctic is less expected yet. The more we perceive a familiar entity in dramatic, unreal, funny, or unusual contexts, the more vivid it is in our minds, and the more easily retrievable later on.

EXPLORE NEW HABITATS

HOW TO APPEAL TO THE FEELING BRAIN

MEMORABLE STORYTELLING

What Are You Making an Audience Feel?

In the finale of the show Mad Men, the main protagonist and advertising guru Don Draper, one of the most compelling lead characters in modern TV, ends up at a hippie commune on the California coast. During a morning therapy session, people are sitting in a circle and sharing their problems, and it looks as if Don is about to take the hot seat. However, another participant, Leonard, unexpectedly gets up, takes the hot seat instead, and tells his story: “I work in an office. People walk right by me. I know they don’t see me,” he laments. “And I go home and I watch my wife and my kids; they don’t look up when I sit down.” He continues his tear-filled confessional: “I had a dream I was on the shelf in the refrigerator. Someone closes the door and the light goes off, and I know everybody’s out there eating. And they open the door and you see everyone smiling and they are happy to see you, but maybe they don’t look right at you and maybe they don’t pick you. And then the door closes again, the light goes off.”

His words are so emotionally vivid, we can picture them and feel them, without the need for real images or PowerPoint slides. There were 3.3 million viewers who tuned in for this final episode of Mad Men, and after three days’ worth of DVR playback, that number jumped to 4.6 million, making it the show’s highest-rated episode. Twitter activity after the final episode reached an all-time high with nearly 50 million impressions. The episode was also considered “the most engaging program on Facebook that Sunday night.”

The refrigerator scene was one of many moments that triggered emotion during the show. There are many other scenes like these throughout the 94 episodes, which have found their way into casual conversations, even of those who did not watch the series. Emotions solidify memory. Think of your romantic partner. Do you remember your first kiss? Now compare the strength of that memory with remembering the first load of laundry you did when you moved into your current place.

Repetition aside, emotion is the most widely discussed variable in relation to memory. Emotional stimuli lead to neurochemical activity in the areas of the brain responsible for encoding, storing, and recalling memories. The amygdala modulates the visual cortex to ensure priority is given to the perception and attention of the event, which helps with encoding. At the storing stage, during sleep, emotion-based memories are given preferential consolidation treatment, and they lead to a relatively permanent trace compared with nonarousing items. Because emotion-based memories may be distinct from neutral ones experienced in the same context, they are easier to retrieve.

The stigma of emotion, especially in business, may come from the perception that emotion is the weak cousin of reason, or according to an old metaphor, emotion is the slave of reason. Emotion may also be seen as inferior and primitive, something that needs to be suppressed because it is dangerous and unreliable. This is far from true where memorable content is concerned.

Sensory perceptions are coded based on their cognitive properties (soft, delicious, strong) as well as their emotional properties (pleasant, unpleasant, exciting, calm). This dual coding of experience helps us understand why some items are forgotten: they may be encoded only once, without an emotional marker. Given that we are exposed to so much stimulation, we constantly have to decide which things to pay attention to. Stored emotional markers help us to discriminate, so that when we are confronted with a similar stimulus, we don’t have to think about how to react—we already know what to do. Just as our eyes perceive light and our ears hear sounds, our emotional system perceives the emotional significance of a stimulus.

How do we include emotion in our messages, especially when content is dry, technical, and complex, and audiences increasingly cynical? Here are a few guidelines.

Clarify What Emotion Means and What Kind You’re Using

Let’s consider this definition: emotions are states we feel when we obtain rewards or avoid punishments. When we look at various stimuli around us, we evaluate and decode their value in terms of predicting what happens next. For example, we see food (reward), and if we can get it, we feel elated. Or we see food, and we want it but can’t get it; therefore we feel frustrated. We feel positive emotions when we advance toward rewards and negative emotions when we deviate from them. We also feel positive emotions when we avoid punishments and negative emotions when we approach them. So to the extent that the nature of the content we create is linked to receiving rewards or avoiding punishments, it can elicit an emotional reaction.

Cognitive psychologist Edmund Rolls has identified and studied emotions that cover the spectrum of four dimensions, which we feel when we:

1. Move toward rewards: pleasure, happiness, elation, ecstasy, love, sexual arousal, trust, empathy, beauty

2. Move away from rewards: frustration, indignation, disbelief, sadness, anger, rage

3. Move away from punishments: relief, liberation

4. Move toward punishments: apprehension, disgust, aversion, fear, terror, unfairness, inequity, uncertainty, social exclusion

When speaking of emotion and its impact on memory, we can also distinguish between (1) the emotional content of the materials we create and (2) the emotional state of the people who receive those materials. Research findings confirm that emotions activate two networks: the “executive control” network (including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and parietal areas) and the emotional “salience” network (including the anterior insular cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, and hypothalamus). Our audiences may comprehend when we present emotional content, such as showing how someone got hurt. However, if the emotional state we provoke is not intense enough, they may be aware of the emotion but not feel it deeply or be moved by it.

Reflecting on your own content, ask this: Which of the four dimensions for emotion could you address without making an audience feel skeptical or cynical?

In general, people adopt a cynical attitude when there is an obligation for reciprocity and that obligation is broken (e.g., employees versus organization). Typically, in business settings, we become cynical in these circumstances:

✵ Expected outcomes created by an organization are unevenly distributed (e.g., high executive compensation and low raises for the staff).

✵ People with lesser skills are promoted.

✵ There are harsh layoffs.

✵ Expectations are unrealistically high.

✵ Communication is inadequate.

✵ Management is characterized by mediocrity.

✵ Role ambiguity and conflict are prevalent in the workplace.

✵ People are suffering from work overload.

If this is the context in which your listeners operate, the context must be addressed first before any other piece of communication has the chance to leave an impression. The most effective piece of content, soaked in the proper emotion (from your view) will fall flat if your listeners are experiencing any of these variables. On the other hand, it is not beneficial to meet audiences in an entirely negative space either. Each time you speak to such audiences, consider lessening the emotion they feel just by a few levels on the same scale, without adopting an entirely different emotion. For cynical audiences that feel anger, by including emotions related to frustration, you still meet them on the same emotional scale but in a way that is toned down. This technique will make them less suspicious of your content.

Of course, cynicism, much like boredom, is not always situational. There are dispositional traits that can lead to cynicism, such as self-esteem, the belief we can control outcomes, reactions to equity (how fair we believe some transactions are), a tendency to view life events as negative, heightened sensitivity, Machiavellianism (viewing others as self-serving), work ethic, or demographic characteristics.

Reflecting on your own content and the emotional state of your audiences, ask: Is the emotion in the content you include appropriate for the emotional state that your audiences are likely to be in when they listen to you?

Let’s see how taking into account the four emotion tracks and an audience’s emotional state plays out in real life. Shark Tank is a TV show in which five investors listen to pitches for various products and services. We can learn from this show when crafting content because it provides abundant examples of persuasive scenarios: people have something to sell, and investors need to be convinced to buy. Kevin O’Leary, one of the investors, is known for caustic criticism but also for metaphors and stories he links to business concepts. In one episode, O’Leary is talking to a couple pitching a kids’ clothing line. He is appalled that the entrepreneurs had 2,700 SKUs, which they felt were needed to keep the line fresh and modern. After several business-related questions, O’Leary tells a story from Greek mythology that expresses his fear of a dangerous business tactic.

O’Leary’s story is about the goddess Persephone, daughter of Zeus and Demeter. “One day she was picking flowers, and she was always tempted to go for more colors. The earth opened, and she fell into the bowels of hell. Here we are in hell.” Fellow investor Mark Cuban pretended to be asleep after the second sentence. Even investor Lori Greiner, who is typically sweet and polite, said to the entrepreneurs in reference to O’Leary, “Hell is his home.”

This is an example in which the speaker’s emotion (O’Leary’s) does not match the emotional state of the others around him. “Fear” means we are moving toward a punishment, and that’s not where the others were. If anything, the high number of SKUs may cause some apprehension, which is on the other emotional scale, moving away from a reward. To avoid the raised eyebrows, a story expressing apprehension would have been better received.

O’Leary knows when he is pushing buttons, so he cut the story short and made the point that too many choices have bad consequences. As we discussed earlier, there are memory trade-offs. You can take the chance and use a different emotional scale than where your audience may be and generate negative emotions. This still results in memory. A negative emotion may be a good place to start, but it is not a good place to end.

Gradually move your audiences to a place that feels optimal for them. Decades of positive psychology research remind us that positive emotions lead to growth and well-being and widen people’s thought-to-action capabilities.

Use Nostalgia

Nostalgia is an emotion that helps to abstract and extract meaning. It is especially effective with cynical audiences because it levels the knowledge in the room. Romancing the past has the potential to strengthen the bond with others. When everyone feels like an equal, people are more likely to trust each other and are more likely to allow themselves to be swayed in a certain direction by others. This is why messages that start with “Remember when …” are so effective. Remember when we only had a few channels on TV? Remember when there were no cell phones? Remember when there was no Facebook?

Nostalgia is associated with persuasion because it has the potential to impact our senses, our preferences, and our loyalty toward an object or a person. Advertisers take advantage of this. I remember a KFM radio station ad that showed a cassette tape with a callout box that said, “iPod, I am your father.” Marketers often invite us to re-create the past through nostalgic consumption. Can you do the same with your audiences? When they are disenchanted by something in the present, can you meet them in an idealized place in the past and build from there?

The formal definition of nostalgia is a “bittersweet longing for home.” During this emotional state, we yearn for an idealized or sanitized version of the past. I can immediately relate to the definition of nostalgia because I grew up in Romania, in the 1980s, under the Communist regime. I often long for our small apartment, eating polenta after a day of unsupervised play in the streets, and not being tempted into prolonged TV watching because we only had two channels. In reminiscing about the “good old days,” we ignore many negative traces.

If my own recollection of that tiny home in Romania were to include an accurate description, I would also mention how we had hot water only once a week, how the electricity would go out at random times for no apparent reason, and how you could hear all your neighbors’ arguments through the thin walls. The two hours of television a day were mostly filled with patriotic poems, sterile Communist propaganda, and censored films. These were times of scarcity and restrictions placed on almost everything, including heat, food, travel, and information. If we were to be accurate about nostalgia, we would define it as a utopian version of the past.

Nostalgia seems to work best when we are torn between the past and the future—whenever there is some anxiety between two worlds, one that used to be and one that is emerging without much direction. Some would call this “disruption.” We’ve heard that word too much in the past few years. If we understand such states of transition, we can appreciate that many of us tend to look back for emotional security. What’s less threatening and more comforting will feel good. The unknown (initially) provokes anxiety.

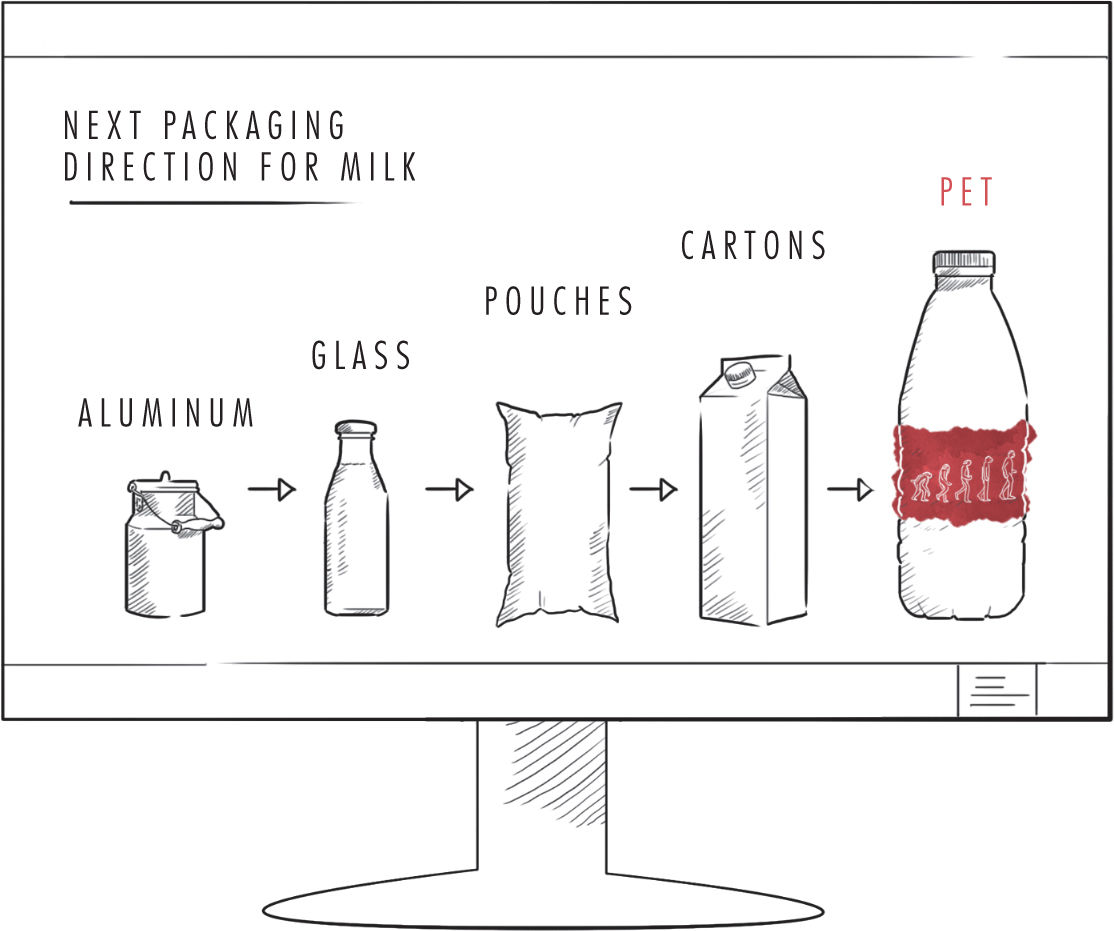

Rose Ballesteros works for Husky, a company that produces plastic injection molding systems (the preforms that give bottles and jars their shapes). Ballesteros is a business manager in the Mexico and Central America region and recently attended one of my workshops. I still remember one of her presentations, in which she used nostalgia to show the evolution of milk packaging. Depending on your age and where you’re from, you may have seen only some of the options in the slide below on TV or in magazines. Nostalgia works well because it evokes the familiarity and security of the past. (PET stands for polyethylene terephthalate, the breakthrough molding material Husky uses.)

NOSTALGIA FEEDS OUR NEED FOR EMOTIONAL SECURITY

Use Wabi-Sabi

One of the most touching exercises I conduct in brain science workshops is asking people to take pictures of their shoes and to type a brief story that their shoes might tell. Notice the authentic emotions attached to these entries:

✵ “These shoes have taken my son to college and allowed me to walk away with confidence!”

✵ “These shoes match every pair of pants I own. So they simplified my life every day by reclaiming 60 seconds of indecision. I get back seven minutes per week for the rest of my life.”

✵ “With these shoes, I finished the NYC Marathon and Camino de Santiago. They mean victory.”

✵ “My friend owed me money and gave me her shoes instead of payment.”

✵ “These shoes have gone from the start of a relationship to its unfortunate conclusion. From no laces to unbreakable laces. From pop music to black metal. They are a collection of my immediate life.”

✵ “These shoes have been through cancer treatment and survived.”

✵ “I really wanted to buy some cooler-looking shoes. Something a little more hip like some pointy suede ones. But I’m too indecisive. So here they are in all their uncoolness.”

The authenticity of these entries makes them impossible to ignore. One technique to help us stay authentic is wabi-sabi, which represents a Japanese view of the world, in which objects are seen as imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. Objects invite us to get close and to relate because they are not fully polished and predictable. Wabi-sabi is an invitation to simplicity but not boredom. A quick search online for wabi-sabi images will remind you that even though the objects they capture are stripped down to their essence, they are emotionally warm. They are simple but not sterile.

Reflect on your own content. Are you staying close to reality in a warm, approachable, modest, and humble way? Can you bring your content down to its essence, without stripping its poetry, even if that implies some imperfections?

In some of my workshops, I ask participants to create or find a picture that is understated and unassuming, yet explains a complex message they want to share with their audience. These are some of my favorites:

✵ A rusted bike stuck in an overgrown tree with the message “How you run your business should adjust to provide customer value and not morph around the legacy systems that are in place.”

✵ A dead flower with the message “Many platforms send alerts days after something happens, so we must use technology that enables real-time reporting.”

✵ A vintage picture of a corner store with the message “Even the most modern infrastructure will eventually be outdated.”

These unpretentious entries provoke emotions, even in the most cynical audiences.

Use Intense Emotions

I remember an old Nike ad with a lot of attitude: “If you’re serious about sports, buy Nike shoes. If you want to dance, buy Reebok.” This works for memory because it adds tension, which generates emotion. It is not a flat statement such as “Buy these shoes to enjoy running.” This would generate an emotion, too, but not a strong one. You don’t need to bash the competition, but it is important to ask, “How intense is the emotion I include in my content?”

Research on psychological arousal finds that high arousal (versus low arousal) leads to better memory. For example, highly intense positive emotions, such as awe, excitement, and amusement, and highly intense negative emotions, such as anger and anxiety, leave a stronger impression compared with their low-arousal counterparts, such as contentment on the positive side and sadness on the negative side.

The more emotionally intense and crisp your statements are, the more likely they are to be repeated. Lines such as “Come with me if you want to live” from Terminator 2, or “I just shot Marvin in the face” from Pulp Fiction, or the pun “I am having an old friend for dinner” from The Silence of the Lambs all express strong emotions.

Messages such as “Here is how to gain access to tools and resources for your job” or “Efficiency of value generation must be quantified and evaluated” are fated to be forgotten if they are not associated with emotional intensity. How do we add emotional intensity? Think of current events, and tie the stories behind them to business messages. David Purdie, PhD, head of Patient Access and Quality of Care at Genentech, told me about a presentation he had to give to some senior managers to convince them to form a new group of analysts. They were suspicious that analytics would really benefit their decision-making processes. Purdie said, “I knew that a traditional presentation with plans and timelines was not going to have the kind of impact I needed to move them to action.” Purdie saved the logistics for a later meeting. During the initial interaction, he shared how the Boston Red Sox used analytics to win the 2004 World Championship and the strong emotion behind a team winning its first World Championship in 85 years. Purdie was excited at the impact of his speech. This was before Moneyball was published or made into a movie, so his story included novelty and surprise for his business audience. Purdie remembers, “My presentation that day started a groundswell of support for the new group, and for the acceptance and adoption of using analytics to inform decision-making. Within a few short years, the group grew to 45 statisticians informing critical decisions all across the company.”

Any content that has a high-arousal characteristic, such as awe, anger, amusement, or anxiety, tends to be more viral, so if we create emotion-based messages, we have the opportunity not only to influence memory but to influence more people’s memory. For example, a study analyzed all New York Times articles published online over a period of three months and discovered that those articles that contained high-arousal emotions were more likely to be e-mailed compared with articles that evoked low-level emotions, such as sadness.

Emotion seems to influence not only whether a message will become repeatable but also how much and how quickly it will be repeated. A German study using SentiStrength—which analyzes emotions in tweets by looking at emotional terms, amplifications (haaaaapy), emoticons, and spelling corrections—examined 165,000 tweets and found that the more positive or negative emotions a tweet expressed, the more quickly and frequently it was retweeted.

LONG STORY SHORT

MEMORABLE STORYTELLING

In this chapter, we addressed the components mandatory for creating content in such a way that it becomes easy for people to search and retrieve it days, weeks, or even years later. When we look at the combination of these elements, they provide the formula for memorable storytelling. Ultimately, all memories include some combination of sensory elements, contextual details, cognitive processes involved when that memory was formed, abstract concepts, and meaning. To make the search for memories easier at Point B, appealing to emotion ensures retrieval because of an additional marker in memory.

I remember an ad from a company called Blanco Attika. It advertised a faucet. The text boldly asked, “Is there emotion in steel? We think so.” A picture showed a close-up of a beautiful faucet, and the description told us how the company “embraced an exclusive blend of artisan craftsmanship and German precision. From the dramatic architecture of the raised rim to the enchanting beauty of the lustrous finish, this unique work of art brilliantly captures light as it captures attention.” I never thought it was possible to have an emotional reaction to faucets. If this company can add emotion to steel, I am convinced you will be able to tap into the emotions of any audience in a way that leaves a lasting impression.

KEEP IN MIND

✵ Memorable stories contain the following components: perceptive (sensory impressions in context and action across a timeline), cognitive (facts, abstract concepts, and meaning), and affective (emotion).

✵ Something is concrete if we can perceive it with our senses. If we can’t perceive it with our senses, we are talking about an idea or a concept, which is abstract. Balance both in your communication and, to avoid habituation, break the pattern an audience learns to expect.

✵ While abstract and concrete are opposites, generic and specific are subsets of each other, with generic being a large group and specific representing an individual item within that group. Zoom in on specific details based on your audience’s level of expertise (advanced audiences can handle abstracts better).

✵ Text and graphics have the potential to be equals in memory. Make pictures easy to label and text easy to picture.

✵ Pair abstract words with concrete pictures to ensure that your audience extracts a uniform meaning from your message.

✵ Use visual metaphors to explain abstract concepts. Steer away from clichéd metaphors by either giving an old metaphor a fresh meaning or using unexpected metaphors.

✵ Wrap abstract words in concrete contexts. Repeat information in the same context for verbatim memory. Vary the context for gist memory.

✵ Appeal to the senses to activate multiple parts of the brain and create more memory traces. The more personal experiences you share, the more opportunities to include sensory details.

✵ Avoid clichéd images. Instead, use vivid images to evoke tension, mystery, wabi-sabi, or nostalgia.

✵ Use strong emotions by showing an audience how to:

![]() Move toward rewards: pleasure, happiness, elation, ecstasy, love, sexual arousal, trust, empathy, beauty.

Move toward rewards: pleasure, happiness, elation, ecstasy, love, sexual arousal, trust, empathy, beauty.

![]() Move away from rewards: frustration, indignation, disbelief, sadness, anger, rage.

Move away from rewards: frustration, indignation, disbelief, sadness, anger, rage.

![]() Move toward punishments: apprehension, disgust, aversion, fear, terror, unfairness, inequity, uncertainty, social exclusion.

Move toward punishments: apprehension, disgust, aversion, fear, terror, unfairness, inequity, uncertainty, social exclusion.

![]() Move away from punishments: relief, liberation.

Move away from punishments: relief, liberation.