Mastering Basic Cheesemaking: The Fun and Fundamentals of Making Cheese at Home - Gianaclis Caldwell (2015)

Part 1. THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MAKING CHEESE

Chapter 1. WHY MAKE CHEESE?

AT ITS MOST FUNDAMENTAL LEVEL, cheese - making is meant to preserve milk. It is a way to feed our families during times of the year when fresh, nourishing milk might not be available. For some of us, it is also a way to make a living. But for many of us, cheese is not made out of necessity, nor because we can make it better than anything commercially available — and certainly not because it is easy. Primarily, we make cheese because we can. We make cheese because it gives us satisfaction. We make cheese because we love cheese.

Cheesemaking and milk fermentation can involve very few steps for simple, fresh cheeses or many steps for long-aged cheeses with complex flavor and delicious nuances. Either way, the process is fun, challenging, and fulfilling, and provides a link not only to long cultural traditions and foodways, but also to the earliest of our ancestors.

THE FIRST CHEESEMAKERS

Many of the best foods in the world involve some stage of fermentation — the process by which bacteria are allowed to act upon and change the food — including chocolate, coffee, cognac, and, of course, cheese. It is believed that fermented milk and beer were the first “processed” foods made by humans. (By processed, I mean that steps other than simple gathering and cooking are involved, rather than what the term implies in today’s convoluted food system.) Fermented grains, barley in particular, preceded fermented milk in terms of discovery and popularity (which is not surprising, really, since beer is still more popular than buttermilk!) Milk fermentation was likely discovered in the same happenstance fashion as beer: by being ignored. The milk of goats, sheep, and cows left to sit in prehistoric Tupperware (earthenware or tightly woven vessels) would have fairly quickly soured, thanks to bacteria naturally collected during milking, on the container and utensils, and in the air, changing the sweet, thin milk into a pleasant, tangy, slightly thick beverage.

This transformation of milk also provided a surprise benefit for our primitive ancestors, who had a problem when it came to milk: past early childhood they couldn’t digest milk sugar (lactose) because they lacked lactase, the enzyme necessary to break it down. Many modern humans, too, lack this enzyme. For some, though, the enzyme that our stomachs produce when we are infants continues to be produced into adulthood and beyond. For those that do not make this handy enzyme, fermented dairy products, especially aged cheeses, are much more digestible because the bacteria in them breaks down the milk sugar before they are consumed.

The fermentation or souring process also makes milk much more tart than when it comes out of the animal. Where there is tang (not the orange-flavored powdered beverage famously promoted by astronauts in the 1960s), there is acid, and where there is acid, there is preservation. Foods that are high in acid don’t spoil as quickly as those that are low in acid. This also made fermented milk of high value to our forebears.

It is believed that the next evolutionary step in cheesemaking, the use of a coagulant to thicken the milk beyond what simple souring could do, also occurred somewhat by accident. Picture our early farmer friends and the vessels available in which milk could be stored: the tightly woven reed basket, the earthenware pot, and the repurposed digestive tract of a beast. It turns out that the stomach of many young mammals is the natural source for a very powerful milk coagulant — what we cheesemakers call rennet. When such an animal stomach was used as a vessel for fresh milk, the rennet would have curdled and thickened the milk while the milk naturally soured, resulting in solid cheese curds and liquid whey. Broken pieces of ancient pottery strainers indicate that cheese curds were being purposefully drained and separated from whey as long as 7,500 years ago. It isn’t too big of a leap to conclude that other means of straining curd also existed — maybe even long before someone figured out how to make a clay colander — but did not survive the ravages of time. No matter what means were used, once humans learned the secrets of making curd, cheesemaking became a part of almost every culture that herded, milked, and butchered animals.

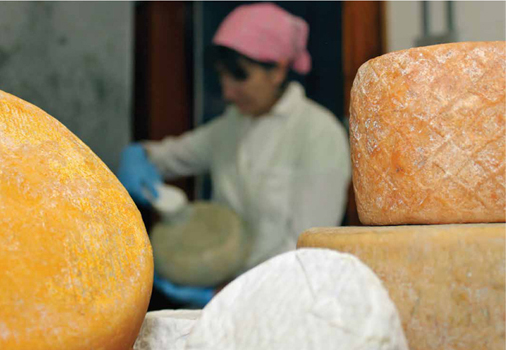

The author and a few of the aged cheeses she makes at Pholia Farm Creamery. CREDIT: BRENTON BURK

THE PEDIGREE OF A CHEESE

Today we have the luxury of buying, eating, and making pretty much any type of cheese we fancy, a privilege unique to our time. We have access to books, recipes, and, even more importantly, technology and supplies. But, it is vital to remember that classic cheese types and varieties evolved due to the innate characteristics and assets of a certain place and time. Cheeses that are heavily salted or stored in salted whey, such as feta, developed in places like Mediterranean Greece, where salt was readily available and other means of preservation, such as cold caves, were not. Delicate surface-ripened French goat’s milk cheeses were the most organic and lovely expression of the qualities inherent in the breeds of goats being milked and the circumstances of location. Enormous wheels of hard, nutty, sweet Swiss types gained their flavor from the grasses and herbs that grow during the high Alpine summer, and their size made it possible to maximize transportation of wheels (on the backs of donkeys) down the mountains when winter grew near.

As a cheesemaker, the pedigree of any cheese is something to honor and appreciate. It is also something to keep in mind when you are unable to exactly reproduce your favorite Spanish blue or English cheddar. The qualitiy that a location imparts on cheese (or wine, beer, or coffee beans) is called terroir (tare-WAH). From the breed of cow, goat, or sheep to what those animals ate and the traditions of the cheesemaker, terroir cannot be cloned. It is what we artisan producers count on when sharing our recipes. We know that no matter what, each finely crafted cheese — when made from the milk of animals nurtured on regionally specific foods — will be a unique expression.

As you learn to make cheese, it is natural and even helpful, to “copy” classic recipes and styles — or at least to attempt to duplicate them. It helps us learn the steps and gives us a frame of reference for our goal. But also it teaches an equally important lesson: the incredible variety of possible outcomes, even when precise steps are followed. Don’t let this unpredictability be discouraging. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that some of the best cheeses made today came about in good part due to a “mistake” or accidental deviation on the part of the cheesemaker. Maybe one day a century from now, an aspiring cheesemaker will be trying to copy a cheese that you created by happenstance.

WHAT IS CHEESEMAKING?

During most of our history as a species, we have not had refrigeration, so foods were either consumed immediately or preserved in some fashion, usually through salting, drying, or souring — or sometimes, as is the case with cheese, all three. Cheese begins with souring, or fermentation. Then it is “dried” through the removal of the whey, salted, and often dried further through pressing and aging. We’ll go over all of the detailed steps in making different categories of cheese later, but let’s take a quick look at the preservation techniques used in making cheese.

A few years ago, if you said the word “fermentation,” you might have gotten some pretty quizzical looks. Other than its usage by avid beer brewers or winemakers, the word was largely consigned to notions of unwanted spoilage. Happily for all of us that love to make and eat great food, fermentation is now quite the en vogue craft. From kombucha (fermented tea) to kimchi and kraut, fermented products are everywhere. Fermentation is simply the eating of sugars by such microscopic life forms as bacteria and yeasts. The by-products of this microbial feast are acid, alcohol, and gas. Fermentation will occur without any help by humans: a tub of beans left in the back of the fridge or a jar of raw milk left on the counter are all wonderful banquets for wild microbes and will ferment if given time, but not necessarily with tasty results (woe to he who opens that inflated tub of old beans and takes a whiff!). But, with a little guidance and intervention, fermentation can produce wonderful, healthy foods.

Clean, raw milk will coagulate naturally when the right native milk flora is present. Commercial cheesemaker, Rona Sullivan of Bonnyclabber Cheese on Sullivan’s Pond Farm in Eastern Virginia, makes her cheeses the old-fashioned way — with no cooking, starter cultures, or rennet. PHOTO BY AND COURTESY OF RONA SULLIVAN

In the case of cheese, fermentation takes place thanks to either naturally occurring (wild) bacteria or added (starter culture) bacteria that consume the milk sugar and create acid. Not all cheeses are fermented (the lessons in chapter 4 have acid added to the milk), but the vast majority are either partially or fully fermented, meaning that almost no milk sugar (food for the bacteria) remains in the cheese. The acid that results from fermentation protects the cheese for longer storage, helps transform the milk into curd, and adds flavor.

The drying step of cheesemaking is accomplished by naturally coaxing the water out of the curd through draining (as in the Neolithic sieve we mentioned earlier), in some cases by adding weight to press out the moisture, and then often by allowing the cheese to sit or hang for an extended period of time. Fortuitously, these steps in removing water also concentrate nutrients and flavor; allow for the further breakdown of milk sugar; give time for the proteins in the milk to break down into more easily digested parts; and create a portable, well preserved, and delicious food.

Salting is an essential step in cheesemaking. Without salt, cheese is bland. Without salt, cheeses do not lose enough moisture and are easily spoiled. Without salt, cheese is not complete.

Bear in mind that there are cheeses with salt, and there are salty cheeses. Those that are traditionally much higher in salt are so because of the traditions involved both in their crafting and in the way they are enjoyed.

To sum it up, cheesemaking is many things: It is natural fermentation and the preservation of food; it is science and art; it is a hobby and a profession; and it is a challenge and a pleasure. Whatever your original motivation was for learning to make cheese, a wonderful journey awaits, one that will teach you many things and provide endless hours of satisfaction — and, of course, delicious cheese!