Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty - Daron Acemoğlu, James A. Robinson (2012)

Chapter 10. THE DIFFUSION OF PROSPERITY

HONOR AMONG THIEVES

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND—or more appropriately, Great Britain after the 1707 union of England, Wales, and Scotland—had a simple solution for dealing with criminals: out of sight, out of mind, or at least out of trouble. They transported many to penal colonies in the empire. Before the War of Independence, the convicted criminals, convicts, were primarily sent to the American colonies. After 1783 the independent United States of America was no longer so welcoming to British convicts, and the authorities in Britain had to find another home for them. They first thought about West Africa. But the climate, with endemic diseases such as malaria and yellow fever, against which Europeans had no immunity, was so deadly that the authorities decided it was unacceptable to send even convicts to the “white man’s graveyard.” Their next option was Australia. Its eastern seaboard had been explored by the great seafarer Captain James Cook. On April 29, 1770, Cook landed in a wonderful inlet, which he called Botany Bay in honor of the rich species found there by the naturalists traveling with him. This seemed like an ideal location to British government officials. The climate was temperate, and the place was as far out of sight and mind as could be imagined.

A fleet of eleven ships packed with convicts was on its way to Botany Bay in January 1788 under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip. On January 26, now celebrated as Australia Day, they set up camp in Sydney Cove, the heart of the modern city of Sydney. They called the colony New South Wales. On board one of the ships, the Alexander, captained by Duncan Sinclair, were a married couple of convicts, Henry and Susannah Cable. Susannah had been found guilty of stealing and was initially sentenced to death. This sentence was later commuted to fourteen years and transportation to the American colonies. That plan fell through with the independence of the United States. In the meantime, in Norwich Castle Jail, Susannah met and fell in love with Henry, a fellow convict. In 1787 she was picked to be transported to the new convict colony in Australia with the first fleet heading there. But Henry was not. By this time Susannah and Henry had a young son, also called Henry. This decision meant the family was to be separated. Susannah was moved to a prison boat moored on the Thames, but the word got out about this wrenching event and reached the ears of a philanthropist, Lady Cadogan. Lady Cadogan organized a successful campaign to reunite the Cables. Now they were both to be transported with young Henry to Australia. Lady Cadogan also raised £20 to purchase goods for them, which they would receive in Australia. They sailed on the Alexander, but when they arrived in Botany Bay, the parcel of goods had vanished, or at least that is what Captain Sinclair claimed.

What could the Cables do? Not much, according to English or British law. Even though in 1787, Britain had inclusive political and economic institutions, this inclusiveness did not extend to convicts, who had practically no rights. They could not own property. They could certainly not sue anyone in court. In fact, they could not even give evidence in court. Sinclair knew this and probably stole the parcel. Though he would never admit it, he did boast that he could not be sued by the Cables. He was right according to British law. And in Britain the whole affair would have ended there. But not in Australia. A writ was issued to David Collins, the judge advocate there, as follows:

Whereas Henry Cable and his wife, new settlers of this place, had before they left England a certain parcel shipped on board the Alexander transport Duncan Sinclair Master, consisting of cloaths and several other articles suitable for their present situation, which were collected and bought at the expence of many charitable disposed persons for the use of the said Henry Cable, his wife and child. Several applications has been made for the express purpose of obtaining the said parcel from the Master of the Alexander now lying at this port, and that without effect (save and except) a small part of the said parcel containing a few books, the residue and remainder, which is of a more considerable value still remains on board the said ship Alexander, the Master of which, seems to be very neglectfull in not causing the same to be delivered, to its respective owners as aforesaid.

Henry and Susannah, since they were both illiterate, could not sign the writ and just put their “crosses” at the bottom. The words “new settlers of this place” were later crossed out, but were highly significant. Someone anticipated that if Henry Cable and his wife were described as convicts, the case would have no hope of proceeding. Someone had come up instead with the idea of calling them new settlers. This was probably a bit too much for Judge Collins to take, and most likely he was the one who had these words struck out. But the writ worked. Collins did not throw out the case, and convened the court, with a jury entirely made up of soldiers. Sinclair was called before the court. Though Collins was less than enthusiastic about the case, and the jury was composed of the people sent to Australia to guard convicts such as the Cables, the Cables won. Sinclair contested the whole affair on the grounds that the Cables were criminals. But the verdict stood, and he had to pay fifteen pounds.

To reach this verdict Judge Collins didn’t apply British law; he ignored it. This was the first civil case adjudicated in Australia. The first criminal case would have appeared equally bizarre to those in Britain. A convict was found guilty of stealing another convict’s bread, which was worth two pence. At the time, such a case would not have come to court, since convicts were not allowed to own anything. Australia was not Britain, and its law would not be just British. And Australia would soon diverge from Britain in criminal and civil law as well as in a host of economic and political institutions.

The penal colony of New South Wales initially consisted of the convicts and their guards, mostly soldiers. There were few “free settlers” in Australia until the 1820s, and the transportation of convicts, though it stopped in New South Wales in 1840, continued until 1868 in Western Australia. Convicts had to perform “compulsory work,” essentially just another name for forced labor, and the guards intended to make money out of it. Initially the convicts had no pay. They were given only food in return for the labor they performed. The guards kept what they produced. But this system, like the ones with which the Virginia Company experimented in Jamestown, did not work very well, because convicts did not have the incentives to work hard or do good work. They were lashed or banished to Norfolk Island, just thirteen square miles of territory situated more than one thousand miles east of Australia in the Pacific Ocean. But since neither banishing nor lashing worked, the alternative was to give them incentives. This was not a natural idea to the soldiers and guards. Convicts were convicts, and they were not supposed to sell their labor or own property. But in Australia there was nobody else to do the work. There were of course Aboriginals, possibly as many as one million at the time of the founding of New South Wales. But they were spread out over a vast continent, and their density in New South Wales was insufficient for the creation of an economy based on their exploitation. There was no Latin American option in Australia. The guards thus embarked on a path that would ultimately lead to institutions that were even more inclusive than those back in Britain. Convicts were given a set of tasks to do, and if they had extra time, they could work for themselves and sell what they produced.

The guards also benefited from the convicts’ new economic freedoms. Production increased, and the guards set up monopolies to sell goods to the convicts. The most lucrative of these was for rum. New South Wales at this time, just like other British colonies, was run by a governor, appointed by the British government. In 1806 Britain appointed William Bligh, the man who seventeen years previously, in 1789, had been captain of the H.M.S. Bounty, during the famous “Mutiny on the Bounty.” Bligh was a strict disciplinarian, a trait that was probably largely responsible for the mutiny. His ways had not changed, and he immediately challenged the rum monopolists. This would lead to another mutiny, this time by the monopolists, led by a former soldier, John Macarthur. The events, which came to be known as the Rum Rebellion, again led to Bligh’s being overpowered by rebels, this time on land rather than aboard the Bounty. Macarthur had Bligh locked up. The British authorities subsequently sent more soldiers to deal with the rebellion. Macarthur was arrested and shipped back to Britain. But he was soon released, and he returned to Australia to play a major role in both the politics and economics of the colony.

The roots of the Rum Rebellion were economic. The strategy of giving the convicts incentives was making a lot of money for men such as Macarthur, who arrived in Australia as a soldier in the second group of ships that landed in 1790. In 1796 he resigned from the army to concentrate on business. By that time he already had his first sheep, and realized that there was a lot of money to be made in sheep farming and wool export. Inland from Sydney were the Blue Mountains, which were finally crossed in 1813, revealing vast expanses of open grassland on the other side. It was sheep heaven. Macarthur was soon the richest man in Australia, and he and his fellow sheep magnates became known as the Squatters, since the land on which they grazed their sheep was not theirs. It was owned by the British government. But at first this was a small detail. The Squatters were the elite of Australia, or, more appropriately, the Squattocracy.

Even with a squattocracy, New South Wales did not look anything like the absolutist regimes of Eastern Europe or of the South American colonies. There were no serfs as in Austria-Hungary and Russia, and no large indigenous populations to exploit as in Mexico and Peru. Instead, New South Wales was like Jamestown, Virginia, in many ways: the elite ultimately found it in their interest to create economic institutions that were significantly more inclusive than those in Austria-Hungary, Russia, Mexico, and Peru. Convicts were the only labor force, and the only way to incentivize them was to pay them wages for the work they were doing.

Convicts were soon allowed to become entrepreneurs and hire other convicts. More notably, they were even given land after completing their sentences, and they had all their rights restored. Some of them started to get rich, even the illiterate Henry Cable. By 1798 he owned a hotel called the Ramping Horse, and he also had a shop. He bought a ship and went into the trade of sealskins. By 1809 he owned at least nine farms of about 470 acres and also a number of shops and houses in Sydney.

The next conflict in New South Wales would be between the elite and the rest of the society, made up of convicts, ex-convicts, and their families. The elite, led by former guards and soldiers such as Macarthur, included some of the free settlers who had been attracted to the colony because of the boom in the wool economy. Most of the property was still in the hands of the elite, and the ex-convicts and their descendants wanted an end to transportation, the opportunity of trial by a jury of their peers, and access to free land. The elite wanted none of these. Their main concern was to establish legal title to the lands they squatted on. The situation was again similar to the events that had transpired in North America more than two centuries earlier. As we saw in chapter 1, the victories of the indentured servants against the Virginia Company were followed by the struggles in Maryland and the Carolinas. In New South Wales, the roles of Lord Baltimore and Sir Anthony Ashley-Cooper were played by Macarthur and the Squatters. The British government was again on the side of the elite, though they also feared that one day Macarthur and the Squatters might be tempted to declare independence.

The British government dispatched John Bigge to the colony in 1819 to head a commission of inquiry into the developments there. Bigge was shocked by the rights that the convicts enjoyed and surprised by the fundamentally inclusive nature of the economic institutions of this penal colony. He recommended a radical overhaul: convicts could not own land, nobody should be allowed to pay convicts wages anymore, pardons were to be restricted, ex-convicts were not to be given land, and punishment was to be made much more draconian. Bigge saw the Squatters as the natural aristocracy of Australia and envisioned an autocratic society dominated by them. This wasn’t to be.

While Bigge was trying to turn back the clock, ex-convicts and their sons and daughters were demanding greater rights. Most important, they realized, again just as in the United States, that to consolidate their economic and political rights fully they needed political institutions that would include them in the process of decision making. They demanded elections in which they could participate as equals and representative institutions and assemblies in which they could hold office.

The ex-convicts and their sons and daughters were led by the colorful writer, explorer, and journalist William Wentworth. Wentworth was one of the leaders of the first expedition that crossed the Blue Mountains, which opened the vast grasslands to the Squatters; a town on these mountains is still named after him. His sympathies were with the convicts, perhaps because of his father, who was accused of highway robbery and had to accept transportation to Australia to avoid trial and possible conviction. At this time, Wentworth was a strong advocate of more inclusive political institutions, an elected assembly, trial by jury for ex-convicts and their families, and an end to transportation to New South Wales. He started a newspaper, the Australian, which would from then on lead the attack on the existing political institutions. Macarthur didn’t like Wentworth and certainly not what he was asking for. He went through a list of Wentworth’s supporters, characterizing them as follows:

sentenced to be hung since he came here

repeatedly flogged at the cart’s tail a

London Jew

Jew publican lately deprived of his license

auctioneer transported for trading in slaves

often flogged here

son of two convicts

a swindler—deeply in debt

an American adventurer

an attorney with a worthless character

a stranger lately failed here in a musick shop

married to the daughter to two convicts

married to a convict who was formerly a tambourine girl.

Macarthur and the Squatters’ vigorous opposition could not stop the tide in Australia, however. The demand for representative institutions was strong and could not be suppressed. Until 1823 the governor had ruled New South Wales more or less on his own. In that year his powers were limited by the creation of a council appointed by the British government. Initially the appointees were from the Squatters and nonconvict elite, Macarthur among them, but this couldn’t last. In 1831 the governor Richard Bourke bowed to pressure and for the first time allowed ex-convicts to sit on juries. Ex-convicts and in fact many new free settlers also wanted transportation of convicts from Britain to stop, because it created competition in the labor market and drove down wages. The Squatters liked low wages, but they lost. In 1840 transportation to New South Wales was stopped, and in 1842 a legislative council was created with two-thirds of its members being elected (the rest appointed). Ex-convicts could stand for office and vote if they held enough property, and many did.

By the 1850s, Australia had introduced adult white male suffrage. The demands of the citizens, ex-convicts and their families, were now far ahead of what William Wentworth had first imagined. In fact, by this time he was on the side of conservatives insisting on an unelected Legislative Council. But just like Macarthur before, Wentworth would not be able to halt the tide toward more inclusive political institutions. In 1856 the state of Victoria, which had been carved out of New South Wales in 1851, and the state of Tasmania would become the first places in the world to introduce an effective secret ballot in elections, which stopped vote buying and coercion. Today we still call the standard method of achieving secrecy in voting in elections the Australian ballot.

The initial circumstances in Sydney, New South Wales, were very similar to those in Jamestown, Virginia, 181 years earlier, though the settlers at Jamestown were mostly indentured laborers, rather than convicts. In both cases the initial circumstances did not allow for the creation of extractive colonial institutions. Neither colony had dense populations of indigenous peoples to exploit, ready access to precious metals such as gold or silver, or soil and crops that would make slave plantations economically viable. The slave trade was still vibrant in the 1780s, and New South Wales could have been filled up with slaves had it been profitable. It wasn’t. Both the Virginia Company and the soldiers and free settlers who ran New South Wales bowed to the pressures, gradually creating inclusive economic institutions that developed in tandem with inclusive political institutions. This happened with even less of a struggle in New South Wales than it had in Virginia, and subsequent attempts to put this trend into reverse failed.

AUSTRALIA, LIKE THE UNITED STATES, experienced a different path to inclusive institutions than the one taken by England. The same revolutions that shook England during the Civil War and then the Glorious Revolution were not needed in the United States or Australia because of the very different circumstances in which those countries were founded—though this of course does not mean that inclusive institutions were established without any conflict, and, in the process, the United States had to throw off British colonialism. In England there was a long history of absolutist rule that was deeply entrenched and required a revolution to remove it. In the United States and Australia, there was no such thing. Though Lord Baltimore in Maryland and John Macarthur in New South Wales might have aspired to such a role, they could not establish a strong enough grip on society for their plans to bear fruit. The inclusive institutions established in the United States and Australia meant that the Industrial Revolution spread quickly to these lands and they began to get rich. The path these countries took was followed by colonies such as Canada and New Zealand.

There were still other paths to inclusive institutions. Large parts of Western Europe took yet a third path to inclusive institutions under the impetus of the French Revolution, which overthrew absolutism in France and then generated a series of interstate conflicts that spread institutional reform across much of Western Europe. The economic consequence of these reforms was the emergence of inclusive economic institutions in most of Western Europe, the Industrial Revolution, and economic growth.

BREAKING THE BARRIERS: THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

For the three centuries prior to 1789, France was ruled by an absolutist monarchy. French society was divided into three segments, the so-called estates. The aristocrats (the nobility) made up the First Estate, the clergy the Second Estate, and everybody else the Third Estate. Different estates were subject to different laws, and the first two estates had rights that the rest of the population did not. The nobility and the clergy did not pay taxes, while the citizens had to pay several different taxes, as we would expect from a regime that was largely extractive. In fact, not only was the Church exempt from taxes, but it also owned large swaths of land and could impose its own taxes on peasants. The monarch, the nobility, and the clergy enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle, while much of the Third Estate lived in dire poverty. Different laws not only guaranteed a greatly advantageous economic position to the nobility and the clergy, but it also gave them political power.

Life in French cities of the eighteenth century was harsh and unhealthy. Manufacturing was regulated by powerful guilds, which generated good incomes for their members but prevented others from entering these occupations or starting new businesses. The so-called ancien régime prided itself on its continuity and stability. Entry by entrepreneurs and talented individuals into new occupations would create instability and was not tolerated. If life in the cities was harsh, life in the villages was probably worse. As we have seen, by this time the most extreme form of serfdom, which tied people to the land and forced them to work for and pay dues to the feudal lords, was long in decline in France. Nevertheless, there were restrictions on mobility and a plethora of feudal dues that the French peasants were required to pay to the monarch, the nobility, and the Church.

Against this background, the French Revolution was a radical affair. On August 4, 1789, the National Constituent Assembly entirely changed French laws by proposing a new constitution. The first article stated:

The National Assembly hereby completely abolishes the feudal system. It decrees that, among the existing rights and dues, both feudal and censuel, all those originating in or representing real or personal serfdom shall be abolished without indemnification.

Its ninth article then continued:

Pecuniary privileges, personal or real, in the payment of taxes are abolished forever. Taxes shall be collected from all the citizens, and from all property, in the same manner and in the same form. Plans shall be considered by which the taxes shall be paid proportionally by all, even for the last six months of the current year.

Thus, in one swoop, the French Revolution abolished the feudal system and all the obligations and dues that it entailed, and it entirely removed the tax exemptions of the nobility and the clergy. But perhaps what was most radical, even unthinkable at the time, was the eleventh article, which stated:

All citizens, without distinction of birth, are eligible to any office or dignity, whether ecclesiastical, civil, or military; and no profession shall imply any derogation.

So there was now equality before the law for all, not only in daily life and business, but also in politics. The reforms of the revolution continued after August 4. It subsequently abolished the Church’s authority to levy special taxes and turned the clergy into employees of the state. Together with the removal of the rigid political and social roles, critical barriers against economic activities were stamped out. The guilds and all occupational restrictions were abolished, creating a more level playing field in the cities.

These reforms were a first step toward ending the reign of the absolutist French monarchs. Several decades of instability and war followed the declarations of August 4. But an irreversible step was taken away from absolutism and extractive institutions and toward inclusive political and economic institutions. These changes would be followed by other reforms in the economy and in politics, ultimately culminating in the Third Republic in 1870, which would bring to France the type of parliamentary system that the Glorious Revolution put in motion in England. The French Revolution created much violence, suffering, instability, and war. Nevertheless, thanks to it, the French did not get trapped with extractive institutions blocking economic growth and prosperity, as did absolutist regimes of Eastern Europe such as Austria-Hungary and Russia.

How did the absolutist French monarchy come to the brink of the 1789 revolution? After all, we have seen that many absolutist regimes were able to survive for long periods of time, even in the midst of economic stagnation and social upheaval. As with most instances of revolutions and radical changes, it was a confluence of factors that opened the way to the French Revolution, and these were intimately related to the fact that Britain was industrializing rapidly. And of course the path was, as usual, contingent, as many attempts to stabilize the regime by the monarchy failed and the revolution turned out to be more successful in changing institutions in France and elsewhere in Europe than many could have imagined in 1789.

Many laws and privileges in France were remnants of medieval times. They not only favored the First and Second Estates relative to the majority of the population but also gave them privileges vis-à-vis the Crown. Louis XIV, the Sun King, ruled France for fifty-four years, between 1661 to his death in 1715, though he actually came to the throne in 1643, at the age of five. He consolidated the power of the monarchy, furthering the process toward greater absolutism that had started centuries earlier. Many monarchs often consulted the so-called Assembly of Notables, consisting of key aristocrats handpicked by the Crown. Though largely consultative, the Assembly still acted as a mild constraint on the monarch’s power. For this reason, Louis XIV ruled without convening the Assembly. Under his reign, France achieved some economic growth—for example, via participation in Atlantic and colonial trade. Louis’s able minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, also oversaw the development of government-sponsored and government-controlled industry, a type of extractive growth. This limited amount of growth benefited almost exclusively the First and Second Estates. Louis XIV also wanted to rationalize the French tax system, because the state often had problems financing its frequent wars, its large standing army, and the King’s own luxurious retinue, consumption, and palaces. Its inability to tax even the minor nobility put severe limits on its revenues.

Though there had been little economic growth, by the time Louis XVI came to power in 1774, there had nevertheless been large changes in society. Moreover, the earlier fiscal problems had turned into a fiscal crisis, and the Seven Years’ War with the British between 1756 and 1763, in which France lost Canada, had been particularly costly. A number of significant figures attempted to balance the royal budget by restructuring the debt and increasing taxes; among them were Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, one of the most famous economists of the time; Jacques Necker, who would also play an important role after the revolution; and Charles Alexandre de Calonne. But none succeeded. Calonne, as part of his strategy, persuaded Louis XVI to summon the Assembly of Notables. The king and his advisers expected the Assembly to endorse his reforms much in the same way as Charles I expected the English Parliament to simply agree to pay for an army to fight the Scottish when he called it in 1640. The Assembly took an unexpected step and decreed that only a representative body, the Estates-General, could endorse such reforms.

The Estates-General was a very different body from the Assembly of Notables. While the latter consisted of the nobility and was largely handpicked by the Crown from among major aristocrats, the former included representatives from all three estates. It had last been convened in 1614. When the Estates-General gathered in 1789 in Versailles, it became immediately clear that no agreement could be reached. There were irreconcilable differences, as the Third Estate saw this as its chance to increase its political power and wanted to have more votes in the Estates-General, which the nobility and the clergy steadfastly opposed. The meeting ended on May 5, 1789, without any resolution, except the decision to convene a more powerful body, the National Assembly, deepening the political crisis. The Third Estate, particularly the merchants, businessmen, professionals, and artisans, who all had demands for greater power, saw these developments as evidence of their increasing clout. In the National Assembly, they therefore demanded even more say in the proceedings and greater rights in general. Their support in the streets all over the country by citizens emboldened by these developments led to the reconstitution of the Assembly as the National Constituent Assembly on July 9.

Meanwhile, the mood in the country, and especially in Paris, was becoming more radical. In reaction, the conservative circles around Louis XVI persuaded him to sack Necker, the reformist finance minister. This led to further radicalization in the streets. The outcome was the famous storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789. From this point onward, the revolution started in earnest. Necker was reinstated, and the revolutionary Marquis de Lafayette was put in charge of the National Guard of Paris.

Even more remarkable than the storming of the Bastille were the dynamics of the National Constituent Assembly, which on August 4, 1789, with its newfound confidence, passed the new constitution, abolishing feudalism and the special privileges of the First and Second Estates. But this radicalization led to fractionalization within the Assembly, since there were many conflicting views about the shape that society should take. The first step was the formation of local clubs, most notably the radical Jacobin Club, which would later take control of the revolution. At the same time, the nobles were fleeing the country in great numbers—the so-called émigrés. Many were also encouraging the king to break with the Assembly and take action, either by himself or with the help of foreign powers, such as Austria, the native country of Queen Marie Antoinette and where most of the émigrés had fled. As many in the streets started to see an imminent threat against the achievements of the revolution over the past two years, radicalization gathered pace. The National Constituent Assembly passed the final version of the constitution on September 29, 1791, turning France into a constitutional monarchy, with equality of rights for all men, no feudal obligations or dues, and an end to all trading restrictions imposed by guilds. France was still a monarchy, but the king now had little role and, in fact, not even his freedom.

But the dynamics of the revolution were then irreversibly altered by the war that broke out in 1792 between France and the “first coalition,” led by Austria. The war increased the resolve and radicalism of the revolutionaries and of the masses (the so-called sans-culottes, which translates as “without knee breeches,” because they could not afford to wear the style of trousers then fashionable). The outcome of this process was the period known as the Terror, under the command of the Jacobin faction led by Robespierre and Saint-Just, unleashed after the executions of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. It led to the executions of not only scores of aristocrats and counterrevolutionaries but also several major figures of the revolution, including the former popular leaders Brissot, Danton, and Desmoulins.

But the Terror soon spun out of control and ultimately came to an end in July 1794 with the execution of its own leaders, including Robespierre and Saint-Just. There followed a phase of relative stability, first under the somewhat ineffective Directory, between 1795 and 1799, and then with more concentrated power in the form of a three-person Consulate, consisting of Ducos, Sieyès, and Napoleon Bonaparte. Already during the Directory, the young general Napoleon Bonaparte had become famous for his military successes, and his influence was only to grow after 1799. The Consulate soon became Napoleon’s personal rule.

The years between 1799 and the end of Napoleon’s reign, 1815, witnessed a series of great military victories for France, including those at Austerlitz, Jena-Auerstadt, and Wagram, bringing continental Europe to its knees. They also allowed Napoleon to impose his will, his reforms, and his legal code across a wide swath of territory. The fall of Napoleon after his final defeat in 1815 would also bring a period of retrenchment, more restricted political rights, and the restoration of the French monarchy under Louis XVII. But all these were simply slowing the ultimate emergence of inclusive political institutions.

The forces unleashed by the revolution of 1789 ended French absolutism and would inevitably, even if slowly, lead to the emergence of inclusive institutions. France, and those parts of Europe where the revolutionary reforms had been exported, would thus take part in the industrialization process already under way in the nineteenth century.

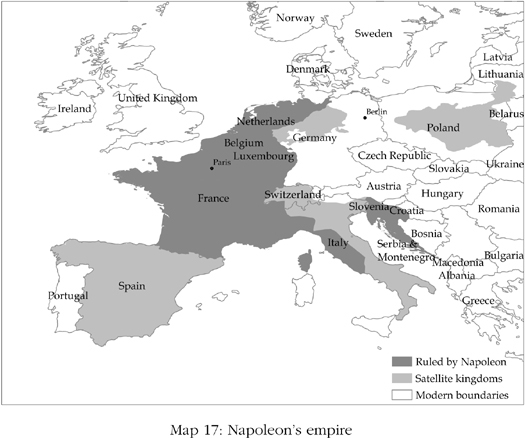

EXPORTING THE REVOLUTION

On the eve of the French Revolution in 1789, there were severe restrictions placed on Jews throughout Europe. In the German city of Frankfurt, for example, their lives were regulated by orders set out in a statute dating from the Middle Ages. There could be no more than five hundred Jewish families in Frankfurt, and they all had to live in a small, walled part of town, the Judengasse, the Jewish ghetto. They could not leave the ghetto at night, on Sundays, or during any Christian festival.

The Judengasse was incredibly cramped. It was a quarter of a mile long but no more than twelve feet wide and in some places less than ten feet wide. Jews lived under constant repression and regulation. Each year, at most two new families could be admitted to the ghetto, and at most twelve Jewish couples could get married, and only if they were both above the age of twenty-five. Jews could not farm; they could also not trade in weapons, spices, wine, or grain. Until 1726 they had to wear specific markers, two concentric yellow rings for men and a striped veil for women. All Jews had to pay a special poll tax.

As the French Revolution erupted, a successful young businessman, Mayer Amschel Rothschild, lived in the Frankfurt Judengasse. By the early 1780s, Rothschild had established himself as the leading dealer in coins, metals, and antiques in Frankfurt. But like all Jews in the city, he could not open a business outside the ghetto or even live outside it.

This was all to change soon. In 1791 the French National Assembly emancipated French Jewry. The French armies were now also occupying the Rhineland and emancipating the Jews of Western Germany. In Frankfurt their effect would be more abrupt and perhaps somewhat unintentional. In 1796 the French bombarded Frankfurt, demolishing half of the Judengasse in the process. Around two thousand Jews were left homeless and had to move outside the ghetto. The Rothschilds were among them. Once outside the ghetto, and now freed from the myriad regulations barring them from entrepreneurship, they could seize new business opportunities. This included a contract to supply grain to the Austrian army, something they would previously not have been allowed to do.

By the end of the decade, Rothschild was one of the richest Jews in Frankfurt and already a well-established businessman. Full emancipation had to wait until 1811; it was finally implemented by Karl von Dalberg, who had been made Grand Duke of Frankfurt in Napoleon’s 1806 reorganization of Germany. Mayer Amschel told his son, “[Y]ou are now a citizen.”

Such events did not end the struggle for Jewish emancipation, since there were subsequent reverses, particularly at the Congress of Vienna of 1815, which formed the post-Napoleonic political settlement. But there was no going back to the ghetto for the Rothschilds. Mayer Amschel and his sons would soon have the largest bank in nineteenth-century Europe, with branches in Frankfurt, London, Paris, Naples, and Vienna.

This was not an isolated event. First the French Revolutionary Armies and then Napoleon invaded large parts of continental Europe, and in almost all the areas they invaded, the existing institutions were remnants of medieval times, empowering kings, princes, and nobility and restricting trade both in cities and the countryside. Serfdom and feudalism were much more important in many of these areas than in France itself. In Eastern Europe, including Prussia and the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary, serfs were tied to the land. In the West this strict form of serfdom had already vanished, but peasants owed to feudal lords various seigneurial fees, taxes, and labor obligations. For example, in the polity of Nassau-Usingen, peasants were subject to 230 different payments, dues, and services. Dues included one that had to be paid after an animal had been slaughtered, called the blood tithe; there was also a bee tithe and a wax tithe. If a piece of property was bought or sold, the lord was owed fees. The guilds regulating all kinds of economic activity in the cities were also typically stronger in these places than in France. In the western German cities of Cologne and Aachen, the adoption of spinning and weaving textile machines was blocked by guilds. Many cities, from Berne in Switzerland to Florence in Italy, were controlled by a few families.

The leaders of the French Revolution and, subsequently, Napoleon exported the revolution to these lands, destroying absolutism, ending feudal land relations, abolishing guilds, and imposing equality before the law—the all-important notion of rule of law, which we will discuss in greater detail in the next chapter. The French Revolution thus prepared not only France but much of the rest of Europe for inclusive institutions and the economic growth that these would spur.

As we have seen, alarmed by the developments in France, several European powers organized around Austria in 1792 to attack France, ostensibly to free King Louis XVI, but in reality to crush the French Revolution. The expectation was that the makeshift armies fielded by the revolution would soon crumble. But after some early defeats, the armies of the new French Republic were victorious in an initially defensive war. There were serious organizational problems to overcome. But the French were ahead of other countries in a major innovation: mass conscription. Introduced in August 1793, mass conscription allowed the French to field large armies and develop a military advantage verging on supremacy even before Napoleon’s famous military skills came on the scene.

Initial military success encouraged the Republic’s leadership to expand France’s borders, with an eye toward creating an effective buffer between the new republic and the hostile monarchs of Prussia and Austria. The French quickly seized the Austrian Netherlands and the United Provinces, essentially today’s Belgium and the Netherlands. The French also took over much of modern-day Switzerland. In all three places, the French had strong control through the 1790s.

Germany was initially hotly contested. But by 1795, the French had firm control over the Rhineland, the western part of Germany lying on the left bank of the Rhine River. The Prussians were forced to recognize this fact under the Treaty of Basel. Between 1795 and 1802, the French held the Rhineland, but not any other part of Germany. In 1802 the Rhineland was officially incorporated into France.

Italy remained the main seat of war in the second half the 1790s, with the Austrians as the opponents. Savoy was annexed by France in 1792, and a stalemate was reached until Napoleon’s invasion in April 1796. In his first major continental campaign, by early 1797, Napoleon had conquered almost all Northern Italy, except for Venice, which was taken by the Austrians. The Treaty of Campo Formio, signed with the Austrians in October 1797, ended the War of the First Coalition and recognized a number of French-controlled republics in Northern Italy. However, the French continued to expand their control over Italy even after this treaty, invading the Papal States and establishing the Roman Republic in March 1798. In January 1799, Naples was conquered and the Parthenopean Republic created. With the exception of Venice, which remained Austrian, the French now controlled the entire Italian peninsula either directly, as in the case of Savoy, or through satellite states, such as the Cisalpine, Ligurian, Roman, and Parthenopean republics.

There was further back-and-forth in the War of the Second Coalition, between 1798 and 1801, but this ended with the French essentially remaining in control. The French revolutionary armies quickly started carrying out a radical process of reform in the lands they’d conquered, abolishing the remaining vestiges of serfdom and feudal land relations and imposing equality before the law. The clergy were stripped of their special status and power, and the guilds in urban areas were stamped out or at the very least much weakened. This happened in the Austrian Netherlands immediately after the French invasion in 1795 and in the United Provinces, where the French founded the Batavian Republic, with political institutions very similar to those in France. In Switzerland the situation was similar, and the guilds as well as feudal landlords and the Church were defeated, feudal privileges removed, and the guilds abolished and expropriated.

What was started by the French Revolutionary Armies was continued, in one form or another, by Napoleon. Napoleon was first and foremost interested in establishing firm control over the territories he conquered. This sometimes involved cutting deals with local elites or putting his family and associates in charge, as during his brief control of Spain and Poland. But Napoleon also had a genuine desire to continue and deepen the reforms of the revolution. Most important, he codified the Roman law and the ideas of equality before the law into a legal system that became known as the Code Napoleon. Napoleon saw this code as his greatest legacy and wished to impose it in every territory he controlled.

Of course, the reforms imposed by the French Revolution and Napoleon were not irreversible. In some places, such as in Hanover, Germany, the old elites were reinstated shortly after Napoleon’s fall and much of what the French achieved was lost for good. But in many other places, feudalism, the guilds, and the nobility were permanently destroyed or weakened. For instance, even after the French left, in many cases the Code Napoleon remained in effect.

All in all, French armies wrought much suffering in Europe, but they also radically changed the lay of the land. In much of Europe, gone were feudal relations; the power of the guilds; the absolutist control of monarchs and princes; the grip of the clergy on economic, social, and political power; and the foundation of ancien régime, which treated different people unequally based on their birth status. These changes created the type of inclusive economic institutions that would then allow industrialization to take root in these places. By the middle of the nineteenth century, industrialization was rapidly under way in almost all the places that the French controlled, whereas places such as Austria-Hungary and Russia, which the French did not conquer, or Poland and Spain, where French hold was temporary and limited, were still largely stagnant.

SEEKING MODERNITY

In the autumn of 1867, Ōkubo Toshimichi, a leading courtier of the feudal Japanese Satsuma domain, traveled from the capital of Edo, now Tokyo, to the regional city of Yamaguchi. On October 14 he met with leaders of the Chōshū domain. He had a simple proposal: they would join forces, march their armies to Edo, and overthrow the shogun, the ruler of Japan. By this time Ōkubo Toshimichi already had the leaders of the Tosa and Aki domains on board. Once the leaders of the powerful Chōshū agreed, a secret Satcho Alliance was formed.

In 1868 Japan was an economically underdeveloped country that had been controlled since 1600 by the Tokugawa family, whose ruler had taken the title shogun (commander) in 1603. The Japanese emperor was sidelined and assumed a purely ceremonial role. The Tokugawa shoguns were the dominant members of a class of feudal lords who ruled and taxed their own domains, among them those of Satsuma, ruled by the Shimazu family. These lords, along with their military retainers, the famous samurai, ran a society that was similar to that of medieval Europe, with strict occupational categories, restrictions on trade, and high rates of taxation on farmers. The shogun ruled from Edo, where he monopolized and controlled foreign trade and banned foreigners from the country. Political and economic institutions were extractive, and Japan was poor.

But the domination of the shogun was not complete. Even as the Tokugawa family took over the country in 1600, they could not control everyone. In the south of the country, the Satsuma domain remained quite autonomous and was even allowed to trade independently with the outside world through the Ryūkyū Islands. It was in the Satsuma capital of Kagoshima where Ōkubo Toshimichi was born in 1830. As the son of a samurai, he, too, became a samurai. His talent was spotted early on by Shimazu Nariakira, the lord of Satsuma, who quickly promoted him in the bureaucracy. At the time, Shimazu Nariakira had already formulated a plan to use Satsuma troops to overthrow the shogun. He wanted to expand trade with Asia and Europe, abolish the old feudal economic institutions, and construct a modern state in Japan. His nascent plan was cut short by his death in 1858. His successor, Shimazu Hisamitsu, was more circumspect, at least initially.

Ōkubo Toshimichi had by now become more and more convinced that Japan needed to overthrow the feudal shogunate, and he eventually convinced Shimazu Hisamitsu. To rally support for their cause, they wrapped it in outrage over the sidelining of the emperor. The treaty (Ōkubo Toshimichi had already signed with the Tosa domain asserted that “a country does not have two monarchs, a home does not have two masters; government devolves to one ruler.” But the real intention was not simply to restore the emperor to power but to change the political and economic institutions completely. On the Tosa side, one of the treaty’s signers was Sakamoto Ryūma. As Satsuma and Chōshū mobilized their armies, Sakamoto Ryūma presented the shogun with an eight-point plan, urging him to resign to avoid civil war. The plan was radical, and though clause 1 stated that “political power of the country should be returned to the Imperial Court, and all decrees issued by the Court,” it included far more than just the restoration of the emperor. Clauses 2, 3, 4, and 5 stated:

2. Two legislative bodies, an Upper and Lower house, should be established, and all government measures should be decided on the basis of general opinion.

3. Men of ability among the lords, nobles and people at large should be employed as councillors, and traditional offices of the past which have lost their purpose should be abolished.

4. Foreign affairs should be carried on according to appropriate regulations worked out on the basis of general opinion.

5. Legislation and regulations of earlier times should be set aside and a new and adequate code should be selected.

Shogun Yoshinobu agreed to resign, and on January 3, 1868, the Meiji Restoration was declared; Emperor Kōmei and, one month later after Kōmei died, his son Meiji were restored to power. Though Satsuma and Chōshū forces now occupied Edo and the imperial capital Kyōto, they feared that the Tokugawas would attempt to regain power and re-create the shogunate. (Ōkubo Toshimichi wanted the Tokugawas crushed forever. He persuaded the emperor to abolish the Tokugawa domain and confiscate their lands. On January 27 the former shogun Yoshinobu attacked Satsuma and Chōshū forces, and civil war broke out; it raged until the summer, when finally the Tokugawas were vanquished.

Following the Meiji Restoration there was a process of transformative institutional reforms in Japan. In 1869 feudalism was abolished, and the three hundred fiefs were surrendered to the government and turned into prefectures, under the control of an appointed governor. Taxation was centralized, and a modern bureaucratic state replaced the old feudal one. In 1869 the equality of all social classes before the law was introduced, and restrictions on internal migration and trade were abolished. The samurai class was abolished, though not without having to put down some rebellions. Individual property rights on land were introduced, and people were allowed freedom to enter and practice any trade. The state became heavily involved in the construction of infrastructure. In contrast to the attitudes of absolutist regimes to railways, in 1869 the Japanese regime formed a steamship line between Tokyo and Osaka and built the first railway between Tokyo and Yokohama. It also began to develop a manufacturing industry, and (Ōkubo Toshimichi, as minister of finance, oversaw the beginning of a concerted effort of industrialization. The lord of Satsuma domain had been a leader in this, building factories for pottery, cannon, and cotton yarn and importing English textile machinery to create the first modern cotton spinning mill in Japan in 1861. He also built two modern shipyards. By 1890 Japan was the first Asian country to adopt a written constitution, and it created a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament, the Diet, and an independent judiciary. These changes were decisive factors in enabling Japan to be the primary beneficiary from the Industrial Revolution in Asia.

IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY both China and Japan were poor nations, languishing under absolutist regimes. The absolutist regime in China had been suspicious of change for centuries. Though there were many similarities between China and Japan—the Tokugawa shogunate had also banned overseas trade in the seventeenth century, as Chinese emperors had done earlier, and were opposed to economic and political change—there were also notable political differences. China was a centralized bureaucratic empire ruled by an absolute emperor. The emperor certainly faced constraints on his power, the most important of which was the threat of rebellion. During the period 1850 to 1864, the whole of southern China was ravaged by the Taiping Rebellion, in which millions died either in conflict or through mass starvation. But opposition to the emperor was not institutionalized.

The structure of Japanese political institutions was different. The shogunate had sidelined the emperor, but as we have seen, the Tokugawa power was not absolute, and domains such as that of the Satsumas maintained independence, even the ability to conduct foreign trade on their own behalf.

As with France, an important consequence of the British Industrial Revolution for China and Japan was military vulnerability. China was humbled by British sea power during the First Opium War, between 1839 and 1842, and the same threat became all too real for the Japanese as U.S. warships, led by Commodore Matthew Perry, pulled into Edo Bay in 1853. The reality that economic backwardness created military backwardness was part of the impetus behind Shimazu Nariakira’s plan to overthrow the shogunate and put in motion the changes that eventually led to the Meiji Restoration. The leaders of the Satsuma domain realized that economic growth—perhaps even Japanese survival—could be achieved only by institutional reforms, but the shogun opposed this because his power was tied to the existing set of institutions. To exact reforms, the shogun had to be overthrown, and he was. The situation was similar in China, but the different initial political institutions made it much harder to overthrow the emperor, something that happened only in 1911. Instead of reforming institutions, the Chinese tried to match the British militarily by importing modern weapons. The Japanese built their own armaments industry.

As a consequence of these initial differences, each country responded differently to the challenges of the nineteenth century, and Japan and China diverged dramatically in the face of the critical juncture created by the Industrial Revolution. While Japanese institutions were being transformed and the economy was embarking on a path of rapid growth, in China forces pushing for institutional change were not strong enough, and extractive institutions persisted largely unabated until they would take a turn for the worse with Mao’s communist revolution in 1949.

ROOTS OF WORLD INEQUALITY

This and the previous three chapters have told the story of how inclusive economic and political institutions emerged in England to make the Industrial Revolution possible, and why certain countries benefited from the Industrial Revolution and embarked on the path to growth, while others did not or, in fact, steadfastly refused to allow even the beginning of industrialization. Whether a country did embark on industrialization was largely a function of its institutions. The United States, which underwent a transformation similar to the English Glorious Revolution, had already developed its own brand of inclusive political and economic institutions by the end of the eighteenth century. It would thus become the first nation to exploit the new technologies coming from the British Isles, and would soon surpass Britain and become the forerunner of industrialization and technological change. Australia followed a similar path to inclusive institutions, even if somewhat later and somewhat less noticed. Its citizens, just like those in England and the United States, had to fight to obtain inclusive institutions. Once these were in place, Australia would launch its own process of economic growth. Australia and the United States could industrialize and grow rapidly because their relatively inclusive institutions would not block new technologies, innovation, or creative destruction.

Not so in most of the other European colonies. Their dynamics would be quite the opposite of those in Australia and the United States. Lack of a native population or resources to be extracted made colonialism in Australia and the United States a very different sort of affair, even if their citizens had to fight hard for their political rights and for inclusive institutions. In the Moluccas as in the many other places Europeans colonized in Asia, in the Caribbean, and in South America, citizens had little chance of winning such a fight. In these places, European colonists imposed a new brand of extractive institutions, or took over whatever extractive institutions they found, in order to be able to extract valuable resources, ranging from spices and sugar to silver and gold. In many of these places, they put in motion a set of institutional changes that would make the emergence of inclusive institutions very unlikely. In some of them they explicitly stamped out whatever burgeoning industry or inclusive economic institutions existed. Most of these places would be in no situation to benefit from industrialization in the nineteenth century or even in the twentieth.

The dynamics in the rest of Europe were also quite different from those in Australia and the United States. As the Industrial Revolution in Britain was gathering speed at the end of the eighteenth century, most European countries were ruled by absolutist regimes, controlled by monarchs and by aristocracies whose major source of income was from their landholdings or from trading privileges they enjoyed thanks to prohibitive entry barriers. The creative destruction that would be wrought by the process of industrialization would erode the leaders’ trading profits and take resources and labor away from their lands. The aristocracies would be economic losers from industrialization. More important, they would also be political losers, as the process of industrialization would undoubtedly create instability and political challenges to their monopoly of political power.

But the institutional transitions in Britain and the Industrial Revolution created new opportunities and challenges for European states. Though there was absolutism in Western Europe, the region had also shared much of the institutional drift that had impacted Britain in the previous millennium. But the situation was very different in Eastern Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and China. These differences mattered for the dissemination of industrialization. Just like the Black Death or the rise of Atlantic trade, the critical juncture created by industrialization intensified the ever-present conflict over institutions in many European nations. A major factor was the French Revolution of 1789. The end of absolutism in France opened the way for inclusive institutions, and the French ultimately embarked on industrialization and rapid economic growth. The French Revolution in fact did more than that. It exported its institutions by invading and forcibly reforming the extractive institutions of several neighboring countries. It thus opened the way to industrialization not only in France, but in Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and parts of Germany and Italy. Farther east the reaction was similar to that after the Black Death, when, instead of crumbling, feudalism intensified. Austria-Hungary, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire fell even further behind economically, but their absolutist monarchies managed to stay in place until the First World War.

Elsewhere in the world, absolutism was as resilient as in Eastern Europe. This was particularly true in China, where the Ming-Qing transition led to a state committed to building a stable agrarian society and hostile to international trade. But there were also institutional differences that mattered in Asia. If China reacted to the Industrial Revolution as Eastern Europe did, Japan reacted in the same way as Western Europe. Just as in France, it took a revolution to change the system, this time one led by the renegade lords of the Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Aki domains. These lords overthrew the shogun, created the Meiji Restoration, and moved Japan onto the path of institutional reforms and economic growth.

We also saw that absolutism was resilient in isolated Ethiopia. Elsewhere on the continent the very same force of international trade that helped to transform English institutions in the seventeenth century locked large parts of western and central Africa into highly extractive institutions via the slave trade. This destroyed societies in some places and led to the creation of extractive slaving states in others.

The institutional dynamics we have described ultimately determined which countries took advantage of the major opportunities present in the nineteenth century onward and which ones failed to do so. The roots of the world inequality we observe today can be found in this divergence. With a few exceptions, the rich countries of today are those that embarked on the process of industrialization and technological change starting in the nineteenth century, and the poor ones are those that did not.