Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty - Daron Acemoğlu, James A. Robinson (2012)

Chapter 9. REVERSING DEVELOPMENT

SPICE AND GENOCIDE

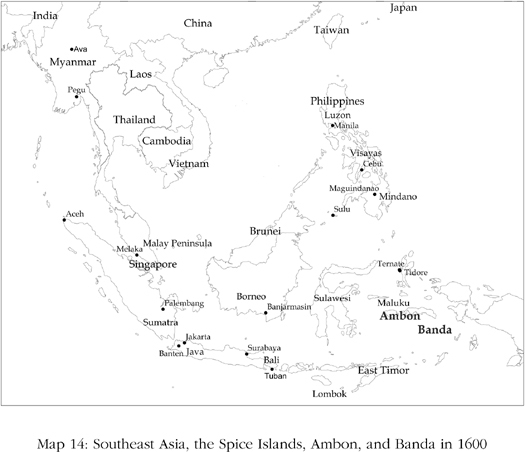

THE MOLUCCAN ARCHIPELAGO in modern Indonesia is made up of three groups of islands. In the early seventeenth century, the northern Moluccas housed the independent kingdoms of Tidore, Ternate, and Bacan. The middle Moluccas were home to the island kingdom of Ambon. In the south were the Banda Islands, a small archipelago that was not yet politically unified. Though they seem remote to us today, the Moluccas were then central to world trade as the only producers of the valuable spices cloves, mace, and nutmeg. Of these, nutmeg and mace grew only in the Banda Islands. Inhabitants of these islands produced and exported these rare spices in exchange for food and manufactured goods coming from the island of Java, from the entrepôt of Melaka on the Malaysian Peninsula, and from India, China, and Arabia.

The first contact the inhabitants had with Europeans was in the sixteenth century, with Portuguese mariners who came to buy spices. Before then spices had to be shipped through the Middle East, via trade routes controlled by the Ottoman Empire. Europeans searched for a passage around Africa or across the Atlantic to gain direct access to the Spice Islands and the spice trade. The Cape of Good Hope was rounded by the Portuguese mariner Bartolomeu Dias in 1488, and India was reached via the same route by Vasco da Gama in 1498. For the first time the Europeans now had their own independent route to the Spice Islands.

The Portuguese immediately set about the task of trying to control the trade in spices. They captured Melaka in 1511. Strategically situated on the western side of the Malaysian Peninsula, merchants from all over Southeast Asia came there to sell their spices to other merchants, Indian, Chinese, and Arabs, who then shipped them to the West. As the Portuguese traveler Tomé Pires put it in 1515: “The trade and commerce between the different nations for a thousand leagues on every hand must come to Melaka … Whoever is lord of Melaka has his hands at the throat of Venice.”

With Melaka in their hands, the Portuguese systematically tried to gain a monopoly of the valuable spice trade. They failed.

The opponents they faced were not negligible. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, there was a great deal of economic development in Southeast Asia based on trade in spices. City-states such as Aceh, Banten, Melaka, Makassar, Pegu, and Brunei expanded rapidly, producing and exporting spices along with other products such as hardwoods.

These states had absolutist forms of government similar to those in Europe in the same period. The development of political institutions was spurred by similar processes, including technological change in methods of warfare and international trade. State institutions became more centralized, with a king at the center claiming absolute power. Like absolutist rulers in Europe, Southeast Asian kings relied heavily on revenues from trade, both engaging in it themselves and granting monopolies to local and foreign elites. As in absolutist Europe, this generated some economic growth but was a far-from-ideal set of economic institutions for economic prosperity, with significant entry barriers and insecure property rights for most. But the process of commercialization was under way even as the Portuguese were trying to establish their dominance in the Indian Ocean.

The presence of Europeans swelled and had a much greater impact with the arrival of the Dutch. The Dutch quickly realized that monopolizing the supply of the valuable spices of the Moluccas would be much more profitable than competing against local or other European traders. In 1600 they persuaded the ruler of Ambon to sign an exclusive agreement that gave them the monopoly on the clove trade in Ambon. With the founding of the Dutch East India Company in 1602, the Dutch attempts to capture the entire spice trade and eliminate their competitors, by hook or by crook, took a turn for the better for the Dutch and for the worse for Southeast Asia. The Dutch East India Company was the second European joint stock company, following the English East India Company, major landmarks in the development of the modern corporation, which would subsequently play a major role in European industrial growth. It was also the second company that had its own army and the power to wage war and colonize foreign lands. With the military power of the company now brought to bear, the Dutch proceeded to eliminate all potential interlopers to enforce their treaty with the ruler of Ambon. They captured a key fort held by the Portuguese in 1605 and forcibly removed all other traders. They then expanded to the northern Moluccas, forcing the rulers of Tidore, Ternate, and Bacan to agree that no cloves could be grown or traded in their territories. The treaty they imposed on Ternate even allowed the Dutch to come and destroy any clove trees they found there.

Ambon was ruled in a manner similar to much of Europe and the Americas during that time. The citizens of Ambon owed tribute to the ruler and were subject to forced labor. The Dutch took over and intensified these systems to extract more labor and more cloves from the island. Prior to the arrival of the Dutch, extended families paid tribute in cloves to the Ambonese elite. The Dutch now stipulated that each household was tied to the soil and should cultivate a certain number of clove trees. Households were also obligated to deliver forced labor to the Dutch.

The Dutch also took control of the Banda Islands, intending this time to monopolize mace and nutmeg. But the Banda Islands were organized very differently from Ambon. They were made up of many small autonomous city-states, and there was no hierarchical social or political structure. These small states, in reality no more than small towns, were run by village meetings of citizens. There was no central authority whom the Dutch could coerce into signing a monopoly treaty and no system of tribute that they could take over to capture the entire supply of nutmeg and mace. At first this meant that the Dutch had to compete with English, Portuguese, Indian, and Chinese merchants, losing the spices to their competitors when they did not pay high prices. Their initial plans of setting up a monopoly of mace and nutmeg dashed, the Dutch governor of Batavia, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, came up with an alternative plan. Coen founded Batavia, on the island of Java, as the Dutch East India Company’s new capital in 1618. In 1621 he sailed to Banda with a fleet and proceeded to massacre almost the entire population of the islands, probably about fifteen thousand people. All their leaders were executed along with the rest, and only a few were left alive, enough to preserve the know-how necessary for mace and nutmeg production. After this genocide was complete, Coen then proceeded to create the political and economic structure necessary for his plan: a plantation society. The islands were divided into sixty-eight parcels, which were given to sixty-eight Dutchmen, mostly former and current employees of the Dutch East India Company. These new plantation owners were taught how to produce the spices by the few surviving Bandanese and could buy slaves from the East India Company to populate the now-empty islands and to produce spices, which would have to be sold at fixed prices back to the company.

The extractive institutions created by the Dutch in the Spice Islands had the desired effects, though, in Banda this was at the cost of fifteen thousand innocent lives and the establishment of a set of economic and political institutions that would condemn the islands to underdevelopment. By the end of the seventeenth century, the Dutch had reduced the world supply of these spices by about 60 percent and the price of nutmeg had doubled.

The Dutch spread the strategy they perfected in the Moluccas to the entire region, with profound implications for the economic and political institutions of the rest of Southeast Asia. The long commercial expansion of several states in the area that had started in the fourteenth century went into reverse. Even the polities which were not directly colonized and crushed by the Dutch East India Company turned inward and abandoned trade. The nascent economic and political change in Southeast Asia was halted in its tracks.

To avoid the threat of the Dutch East India Company, several states abandoned producing crops for export and ceased commercial activity. Autarky was safer than facing the Dutch. In 1620 the state of Banten, on the island of Java, cut down its pepper trees in the hope that this would induce the Dutch to leave it in peace. When a Dutch merchant visited Maguindanao, in the southern Philippines, in 1686, he was told, “Nutmeg and cloves can be grown here, just as in Malaku. They are not there now because the old Raja had all of them ruined before his death. He was afraid the Dutch Company would come to fight with them about it.” What a trader heard about the ruler of Maguindanao in 1699 was similar: “He had forbidden the continued planting of pepper so that he could not thereby get involved in war whether with the [Dutch] company or with other potentates.” There was de-urbanization and even population decline. In 1635 the Burmese moved their capital from Pegu, on the coast, to Ava, far inland up the Irrawaddy River.

We do not know what the path of economic and political development of Southeast Asian states would have been without Dutch aggression. They may have developed their own brand of absolutism, they may have remained in the same state they were in at the end of the sixteenth century, or they may have continued their commercialization by gradually adopting more and more inclusive institutions. But as in the Moluccas, Dutch colonialism fundamentally changed their economic and political development. The people in Southeast Asia stopped trading, turned inward, and became more absolutist. In the next two centuries, they would be in no position to take advantage of the innovations that would spring up in the Industrial Revolution. And ultimately their retreat from trade would not save them from Europeans; by the end of the eighteenth century, nearly all were part of European colonial empires.

WE SAW IN CHAPTER 7 how European expansion into the Atlantic fueled the rise of inclusive institutions in Britain. But as illustrated by the experience of the Moluccas under the Dutch, this expansion sowed the seeds of underdevelopment in many diverse corners of the world by imposing, or further strengthening existing, extractive institutions. These either directly or indirectly destroyed nascent commercial and industrial activity throughout the globe or they perpetuated institutions that stopped industrialization. As a result, as industrialization was spreading in some parts of the world, places that were part of European colonial empires stood no chance of benefiting from these new technologies.

THE ALL-TOO-USUAL INSTITUTION

In Southeast Asia the spread of European naval and commercial power in the early modern period curtailed a promising period of economic expansion and institutional change. In the same period as the Dutch East India Company was expanding, a very different sort of trade was intensifying in Africa: the slave trade.

In the United States, southern slavery was often referred to as the “peculiar institution.” But historically, as the great classical scholar Moses Finlay pointed out, slavery was anything but peculiar, it was present in almost every society. It was, as we saw earlier, endemic in Ancient Rome and in Africa, long a source of slaves for Europe, though not the only one.

In the Roman period slaves came from Slavic peoples around the Black Sea, from the Middle East, and also from Northern Europe. But by 1400, Europeans had stopped enslaving each other. Africa, however, as we saw in chapter 6, did not undergo the transition from slavery to serfdom as did medieval Europe. Before the early modern period, there was a vibrant slave trade in East Africa, and large numbers of slaves were transported across the Sahara to the Arabian Peninsula. Moreover, the large medieval West African states of Mali, Ghana, and Songhai made heavy use of slaves in the government, the army, and agriculture, adopting organizational models from the Muslim North African states with whom they traded.

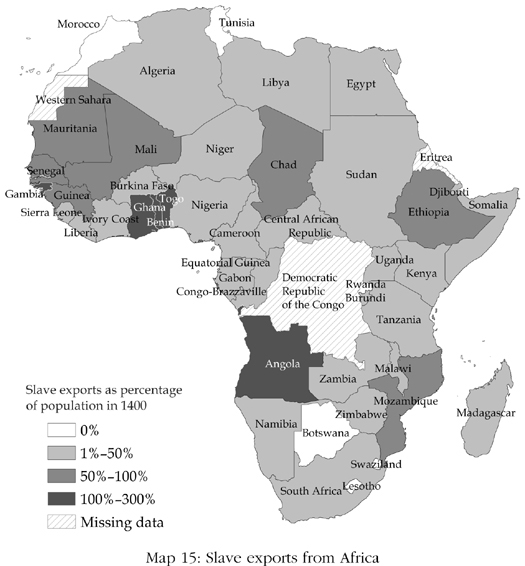

It was the development of the sugar plantation colonies of the Caribbean beginning in the early seventeenth century that led to a dramatic escalation of the international slave trade and to an unprecedented increase in the importance of slavery within Africa itself. In the sixteenth century, probably about 300,000 slaves were traded in the Atlantic. They came mostly from Central Africa, with heavy involvement of Kongo and the Portuguese based farther south in Luanda, now the capital of Angola. During this time, the trans-Saharan slave trade was still larger, with probably about 550,000 Africans moving north as slaves. In the seventeenth century, the situation reversed. About 1,350,000 Africans were sold as slaves in the Atlantic trade, the majority now being shipped to the Americas. The numbers involved in the Saharan trade were relatively unchanged. The eighteenth century saw another dramatic increase, with about 6,000,000 slaves being shipped across the Atlantic and maybe 700,000 across the Sahara. Adding the figures up over periods and parts of Africa, well over 10,000,000 Africans were shipped out of the continent as slaves.

Map 15 (this page) gives some sense of the scale of the slave trade. Using modern country boundaries, it depicts estimates of the cumulative extent of slavery between 1400 and 1900 as a percent of population in 1400. Darker colors show more intense slavery. For example, in Angola, Benin, Ghana, and Togo, total cumulative slave exports amounted to more than the entire population of the country in 1400.

The sudden appearance of Europeans all around the coast of Western and Central Africa eager to buy slaves could not but have a transformative impact on African societies. Most slaves who were shipped to the Americas were war captives subsequently transported to the coast. The increase in warfare was fueled by huge imports of guns and ammunition, which the Europeans exchanged for slaves. By 1730 about 180,000 guns were being imported every year just along the West African coast, and between 1750 and the early nineteenth century, the British alone sold between 283,000 and 394,000 guns a year. Between 1750 and 1807, the British sold an extraordinary 22,000 tons of gunpowder, making an average of about 384,000 kilograms annually, along with 91,000 kilograms of lead per year. Farther to the south, the trade was just as vigorous. On the Loango coast, north of the Kingdom of Kongo, Europeans sold about 50,000 guns a year.

All this warfare and conflict not only caused major loss of life and human suffering but also put in motion a particular path of institutional development in Africa. Before the early modern era, African societies were less centralized politically than those of Eurasia. Most polities were small scale, with tribal chiefs and perhaps kings controlling land and resources. Many, as we showed with Somalia, had no structure of hierarchical political authority at all. The slave trade initiated two adverse political processes. First, many polities initially became more absolutist, organized around a single objective: to enslave and sell others to European slavers. Second, as a consequence but, paradoxically, in opposition to the first process, warring and slaving ultimately destroyed whatever order and legitimate state authority existed in sub-Saharan Africa. Apart from warfare, slaves were also kidnapped and captured by small-scale raiding. The law also became a tool of enslavement. No matter what crime you committed, the penalty was slavery. The English merchant Francis Moore observed the consequences of this along the Senegambia coast of West Africa in the 1730s:

Since this slave trade has been us’d, all punishments are changed into slavery; there being an advantage on such condemnations, they strain for crimes very hard, in order to get the benefit of selling the criminal. Not only murder, theft and adultery, are punished by selling the criminal for slave, but every trifling case is punished in the same manner.

Institutions, even religious ones, became perverted by the desire to capture and sell slaves. One example is the famous oracle at Arochukwa, in eastern Nigeria. The oracle was widely believed to speak for a prominent deity in the region respected by the major local ethnic groups, the Ijaw, the Ibibio, and the Igbo. The oracle was approached to settle disputes and adjudicate on disagreements. Plaintiffs who traveled to Arochukwa to face the oracle had to descend from the town into a gorge of the Cross River, where the oracle was housed in a tall cave, the front of which was lined with human skulls. The priests of the oracle, in league with the Aro slavers and merchants, would dispense the decision of the oracle. Often this involved people being “swallowed” by the oracle, which actually meant that once they had passed through the cave, they were led away down the Cross River and to the waiting ships of the Europeans. This process in which all laws and customs were distorted and broken to capture slaves and more slaves had devastating effects on political centralization, though in some places it did lead to the rise of powerful states whose main raison d’être was raiding and slaving. The Kingdom of Kongo itself was probably the first African state to experience a metamorphosis into a slaving state, until it was destroyed by civil war. Other slaving states arose most prominently in West Africa and included Oyo in Nigeria, Dahomey in Benin, and subsequently Asante in Ghana.

The expansion of the state of Oyo in the middle of the seventeenth century, for example, is directly related to the increase of slave exports on the coast. The state’s power was the result of a military revolution that involved the import of horses from the north and the formation of a powerful cavalry that could decimate opposing armies. As Oyo expanded south toward the coast, it crushed the intervening polities and sold many of their inhabitants for slaves. In the period between 1690 and 1740, Oyo established its monopoly in the interior of what came to be known as the Slave Coast. It is estimated that 80 to 90 percent of the slaves sold on the coast were the result of these conquests. A similar dramatic connection between warfare and slave supply came farther west in the eighteenth century, on the Gold Coast, the area that is now Ghana. After 1700 the state of Asante expanded from the interior, in much the same way as Oyo had previously. During the first half of the eighteenth century, this expansion triggered the so-called Akan Wars, as Asante defeated one independent state after another. The last, Gyaman, was conquered in 1747. The preponderance of the 375,000 slaves exported from the Gold Coast between 1700 and 1750 were captives taken in these wars.

Probably the most obvious impact of this massive extraction of human beings was demographic. It is difficult to know with any certitude what the population of Africa was before the modern period, but scholars have made various plausible estimates of the impact of the slave trade on the population. The historian Patrick Manning estimates that the population of those areas of West and West-Central Africa that provided slaves for export was around twenty-two to twenty-five million in the early eighteenth century. On the conservative assumption that during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries these areas would have experienced a rate of population growth of about half a percent a year without the slave trade, Manning estimated that the population of this region in 1850 ought to have been at least forty-six to fifty-three million. In fact, it was about one-half of this.

This massive difference was not only due to about eight million people being exported as slaves from this region between 1700 and 1850, but the millions likely killed by continual internal warfare aimed at capturing slaves. Slavery and the slave trade in Africa further disrupted family and marriage structures and may also have reduced fertility.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, a strong movement to abolish the slave trade began to gain momentum in Britain, led by the charismatic figure of William Wilberforce. After repeated failures, in 1807 the abolitionists persuaded the British Parliament to pass a bill making the slave trade illegal. The United States followed with a similar measure the next year. The British government went further, though: it actively sought to implement this measure by stationing naval squadrons in the Atlantic to try to stamp out the slave trade. Though it took some time for these measures to be truly effective, and it was not until 1834 that slavery itself was abolished in the British Empire, the days of the Atlantic slave trade, by far the largest part of the trade, were numbered.

Though the end of the slave trade after 1807 did reduce the external demand for slaves from Africa, this did not mean that slavery’s impact on African societies and institutions would magically melt away. Many African states had become organized around slaving, and the British putting an end to the trade did not change this reality. Moreover, slavery had become much more prevalent within Africa itself. These factors would ultimately shape the path of development in Africa not only before but also after 1807.

In the place of slavery came “legitimate commerce,” a phrase coined for the export from Africa of new commodities not tied to the slave trade. These goods included palm oil and kernels, peanuts, ivory, rubber, and gum arabic. As European and North American incomes expanded with the spread of the Industrial Revolution, demand for many of these tropical products rose sharply. Just as African societies took aggressive advantage of the economic opportunities presented by the slave trade, they did the same with legitimate commerce. But they did so in a peculiar context, one in which slavery was a way of life but the external demand for slaves had suddenly dried up. What were all these slaves to do now that they could not be sold to Europeans? The answer was simple: they could be profitably put to work, under coercion, in Africa, producing the new items of legitimate commerce.

One of the best documented examples was in Asante, in modern Ghana. Prior to 1807, the Asante Empire had been heavily involved in the capturing and export of slaves, bringing them down to the coast to be sold at the great slaving castles of Cape Coast and Elmina. After 1807, with this option closed off, the Asante political elite reorganized their economy. However, slaving and slavery did not end. Rather, slaves were settled on large plantations, initially around the capital city of Kumase, but later spread throughout the empire (corresponding to most of the interior of Ghana). They were employed in the production of gold and kola nuts for export, but also grew large quantities of food and were intensively used as porters, since Asante did not use wheeled transportation. Farther east, similar adaptations took place. In Dahomey, for example, the king had large palm oil plantations near the coastal ports of Whydah and Porto Novo, all based on slave labor.

So the abolition of the slave trade, rather than making slavery in Africa wither away, simply led to a redeployment of the slaves, who were now used within Africa rather than in the Americas. Moreover, many of the political institutions the slave trade had wrought in the previous two centuries were unaltered and patterns of behavior persisted. For example, in Nigeria in the 1820s and ’30s the once-great Oyo Kingdom collapsed. It was undermined by civil wars and the rise of the Yoruba city-states, such as Illorin and Ibadan, that were directly involved in the slave trade, to its south. In the 1830s, the capital of Oyo was sacked, and after that the Yoruba cities contested power with Dahomey for regional dominance. They fought an almost continuous series of wars in the first half of the century, which generated a massive supply of slaves. Along with this went the normal rounds of kidnapping and condemnation by oracles and smaller-scale raiding. Kidnapping was such a problem in some parts of Nigeria that parents would not let their children play outside for fear they would be taken and sold into slavery.

As a result slavery, rather than contracting, appears to have expanded in Africa throughout the nineteenth century. Though accurate figures are hard to come by, a number of existing accounts written by travelers and merchants during this time suggest that in the West African kingdoms of Asante and Dahomey and in the Yoruba city-states well over half of the population were slaves. More accurate data exist from early French colonial records for the western Sudan, a large swath of western Africa, stretching from Senegal, via Mali and Burkina Faso, to Niger and Chad. In this region 30 percent of the population was enslaved in 1900.

Just as with the emergence of legitimate commerce, the advent of formal colonization after the Scramble for Africa failed to destroy slavery in Africa. Though much of European penetration into Africa was justified on the grounds that slavery had to be combated and abolished, the reality was different. In most parts of colonial Africa, slavery continued well into the twentieth century. In Sierra Leone, for example, it was only in 1928 that slavery was finally abolished, even though the capital city of Freetown was originally established in the late eighteenth century as a haven for slaves repatriated from the Americas. It then became an important base for the British antislavery squadron and a new home for freed slaves rescued from slave ships captured by the British navy. Even with this symbolism slavery lingered in Sierra Leone for 130 years. Liberia, just south of Sierra Leone, was likewise founded for freed American slaves in the 1840s. Yet there, too, slavery lingered into the twentieth century; as late as the 1960s, it was estimated that one-quarter of the labor force were coerced, living and working in conditions close to slavery. Given the extractive economic and political institutions based on the slave trade, industrialization did not spread to sub-Saharan Africa, which stagnated or even experienced economic retardation as other parts of the world were transforming their economies.

MAKING A DUAL ECONOMY

The “dual economy” paradigm, originally proposed in 1955 by Sir Arthur Lewis, still shapes the way that most social scientists think about the economic problems of less-developed countries. According to Lewis, many less-developed or underdeveloped economies have a dual structure and are divided into a modern sector and a traditional sector. The modern sector, which corresponds to the more developed part of the economy, is associated with urban life, modern industry, and the use of advanced technologies. The traditional sector is associated with rural life, agriculture, and “backward” institutions and technologies. Backward agricultural institutions include the communal ownership of land, which implies the absence of private property rights on land. Labor was used so inefficiently in the traditional sector, according to Lewis, that it could be reallocated to the modern sector without reducing the amount the rural sector could produce. For generations of development economists building on Lewis’s insights, the “problem of development” has come to mean moving people and resources out of the traditional sector, agriculture and the countryside, and into the modern sector, industry and cities. In 1979 Lewis received the Nobel Prize for his work on economic development.

Lewis and development economists building on his work were certainly right in identifying dual economies. South Africa was one of the clearest examples, split into a traditional sector that was backward and poor and a modern one that was vibrant and prosperous. Even today the dual economy Lewis identified is everywhere in South Africa. One of the most dramatic ways to see this is by driving across the border between the state of KwaZulu-Natal, formerly Natal, and the state of the Transkei. The border follows the Great Kei River. To the east of the river in Natal, along the coast, are wealthy beachfront properties on wide expanses of glorious sandy beaches. The interior is covered with lush green sugarcane plantations. The roads are beautiful; the whole area reeks of prosperity. Across the river, it is as if it were a different time and a different country. The area is largely devastated. The land is not green, but brown and heavily deforested. Instead of affluent modern houses with running water, toilets, and all the modern conveniences, people live in makeshift huts and cook on open fires. Life is certainly traditional, far from the modern existence to the east of the river. By now you will not be surprised that these differences are linked with major differences in economic institutions between the two sides of the river.

To the east, in Natal, we have private property rights, functioning legal systems, markets, commercial agriculture, and industry. To the west, the Transkei had communal property in land and all-powerful traditional chiefs until recently. Looked at through the lens of Lewis’s theory of dual economy, the contrast between the Transkei and Natal illustrates the problems of African development. In fact, we can go further, and note that, historically, all of Africa was like the Transkei, poor with premodern economic institutions, backward technology, and rule by chiefs. According to this perspective, then, economic development should simply be about ensuring that the Transkei eventually turns into Natal.

This perspective has much truth to it but misses the entire logic of how the dual economy came into existence and its relationship to the modern economy. The backwardness of the Transkei is not just a historic remnant of the natural backwardness of Africa. The dual economy between the Transkei and Natal is in fact quite recent, and is anything but natural. It was created by the South African white elites in order to produce a reservoir of cheap labor for their businesses and reduce competition from black Africans. The dual economy is another example of underdevelopment created, not of underdevelopment as it naturally emerged and persisted over centuries.

South Africa and Botswana, as we will see later, did avoid most of the adverse effects of the slave trade and the wars it wrought. South Africans’ first major interaction with Europeans came when the Dutch East India Company founded a base in Table Bay, now the harbor of Cape Town, in 1652. At this time the western part of South Africa was sparsely settled, mostly by hunter-gatherers called the Khoikhoi people. Farther east, in what is now the Ciskei and Transkei, there were densely populated African societies specializing in agriculture. They did not initially interact heavily with the new colony of the Dutch, nor did they become involved in slaving. The South African coast was far removed from slave markets, and the inhabitants of the Ciskei and Transkei, known as the Xhosa, were just far enough inland not to attract anyone’s attention. As a consequence, these societies did not feel the brunt of many of the adverse currents that hit West and Central Africa.

The isolation of these places changed in the nineteenth century. For the Europeans there was something very attractive about the climate and the disease environment of South Africa. Unlike West Africa, for example, South Africa had a temperate climate that was free of the tropical diseases such as malaria and yellow fever that had turned much of Africa into the “white man’s graveyard” and prevented Europeans from settling or even setting up permanent outposts. South Africa was a much better prospect for European settlement. European expansion into the interior began soon after the British took over Cape Town from the Dutch during the Napoleonic Wars. This precipitated a long series of Xhosa wars as the settlement frontier expanded further inland. The penetration into the South African interior was intensified in 1835, when the remaining Europeans of Dutch descent, who would become known as Afrikaners or Boers, started their famous mass migration known as the Great Trek away from the British control of the coast and the Cape Town area. The Afrikaners subsequently founded two independent states in the interior of Africa, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal.

The next stage in the development of South Africa came with the discovery of vast diamond reserves in Kimberly in 1867 and of rich gold mines in Johannesburg in 1886. This huge mineral wealth in the interior immediately convinced the British to extend their control over all of South Africa. The resistance of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal led to the famous Boer Wars in 1880-1881 and 1899-1902. After initial unexpected defeat, the British managed to merge the Afrikaner states with the Cape Province and Natal, to found the Union of South Africa in 1910. Beyond the fighting between Afrikaners and the British, the development of the mining economy and the expansion of European settlement had other implications for the development of the area. Most notably, they generated demand for food and other agricultural products and created new economic opportunities for native Africans both in agriculture and trade.

The Xhosa, in the Ciskei and Transkei, reacted quickly to these economic opportunities, as the historian Colin Bundy documented. As early as 1832, even before the mining boom, a Moravian missionary in the Transkei observed the new economic dynamism in these areas and noted the demand from the Africans for the new consumer goods that the spread of Europeans had begun to reveal to them. He wrote, “To obtain these objects, they look … to get money by the labour of their hands, and purchase clothes, spades, ploughs, wagons and other useful articles.”

The civil commissioner John Hemming’s description of his visit to Fingoland in the Ciskei in 1876 is equally revealing. He wrote that he was

struck with the very great advancement made by the Fingoes in a few years … Wherever I went I found substantial huts and brick or stone tenements. In many cases, substantial brick houses had been erected … and fruit trees had been planted; wherever a stream of water could be made available it had been led out and the soil cultivated as far as it could be irrigated; the slopes of the hills and even the summits of the mountains were cultivated wherever a plough could be introduced. The extent of the land turned over surprised me; I have not seen such a large area of cultivated land for years.

As in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the use of the plow was new in agriculture, but when given the opportunity, African farmers seemed to have been quite ready to adopt the technology. They were also prepared to invest in wagons and irrigation works.

As the agricultural economy developed, the rigid tribal institutions started to give way. There is a great deal of evidence that changes in property rights to land took place. In 1879 the magistrate in Umzimkulu of Griqualand East, in the Transkei, noted “the growing desire of the part of natives to become proprietors of land—they have purchased 38,000 acres.” Three years later he recorded that around eight thousand African farmers in the district had bought and started to work on ninety thousand acres of land.

Africa was certainly not on the verge of an Industrial Revolution, but real change was under way. Private property in land had weakened the chiefs and enabled new men to buy land and make their wealth, something that was unthinkable just decades earlier. This also illustrates how quickly the weakening of extractive institutions and absolutist control systems can lead to newfound economic dynamism. One of the success stories was Stephen Sonjica in the Ciskei, a self-made farmer from a poor background. In an address in 1911, Sonjica noted how when he first expressed to his father his desire to buy land, his father had responded: “Buy land? How can you want to buy land? Don’t you know that all land is God’s, and he gave it to the chiefs only?” Sonjica’s father’s reaction was understandable. But Sonjica was not deterred. He got a job in King William’s Town and noted:

I cunningly opened a private bank account into which I diverted a portion of my savings … This went only until I had saved eighty pounds … [I bought] a span of oxen with yokes, gear, plough and the rest of agricultural paraphernalia … I now purchased a small farm … I cannot too strongly recommend [farming] as a profession to my fellow man … They should however adopt modern methods of profit making.

An extraordinary piece of evidence supporting the economic dynamism and prosperity of African farmers in this period is revealed in a letter sent in 1869 by a Methodist missionary, W. J. Davis. Writing to England, he recorded with pleasure that he had collected forty-six pounds in cash “for the Lancashire Cotton Relief Fund.” In this period the prosperous African farmers were donating money for relief of the poor English textile workers!

This new economic dynamism, not surprisingly, did not please the traditional chiefs, who, in a pattern that is by now familiar to us, saw this as eroding their wealth and power. In 1879 Matthew Blyth, the chief magistrate of the Transkei, observed that there was opposition to surveying the land so that it could be divided into private property. He recorded that “some of the chiefs … objected, but most of the people were pleased … the chiefs see that the granting of individual titles will destroy their influence among the headmen.”

Chiefs also resisted improvements made on the lands, such as the digging of irrigation ditches or the building of fences. They recognized that these improvements were just a prelude to individual property rights to the land, the beginning of the end for them. European observers even noted that chiefs and other traditional authorities, such as witch doctors, attempted to prohibit all “European ways,” which included new crops, tools such as plows, and items of trade. But the integration of the Ciskei and the Transkei into the British colonial state weakened the power of the traditional chiefs and authorities, and their resistance would not be enough to stop the new economic dynamism in South Africa. In Fingoland in 1884, a European observer noted that the people had

transferred their allegiance to us. Their chiefs have been changed to a sort of titled landowner … without political power. No longer afraid of the jealousy of the chief or of the deadly weapon … the witchdoctor, which strikes down the wealthy cattle owner, the able counsellor, the introduction of novel customs, the skilful agriculturalist, reducing them all to the uniform level of mediocrity—no longer apprehensive of this, the Fingo clansman … is a progressive man. Still remaining a peasant farmer … he owns wagons and ploughs; he opens water furroughs for irrigation; he is the owner of a flock of sheep.

Even a modicum of inclusive institutions and the erosion of the powers of the chiefs and their restrictions were sufficient to start a vigorous African economic boom. Alas, it would be short lived. Between 1890 and 1913 it would come to an abrupt end and go into reverse. During this period two forces worked to destroy the rural prosperity and dynamism that Africans had created in the previous fifty years. The first was antagonism by European farmers who were competing with Africans. Successful African farmers drove down the price of crops that Europeans also produced. The response of Europeans was to drive the Africans out of business. The second force was even more sinister. The Europeans wanted a cheap labor force to employ in the burgeoning mining economy, and they could ensure this cheap supply only by impoverishing the Africans. This they went about methodically over the next several decades.

The 1897 testimony of George Albu, the chairman of the Association of Mines, given to a Commission of Inquiry pithily describes the logic of impoverishing Africans so as to obtain cheap labor. He explained how he proposed to cheapen labor by “simply telling the boys that their wages are reduced.” His testimony goes as follows:

Commission: Suppose the kaffirs [black Africans] retire back to their kraal [cattle pen]? Would you be in favor of asking the Government to enforce labour?

Albu: Certainly … I would make it compulsory … Why should a nigger be allowed to do nothing? I think a kaffir should be compelled to work in order to earn his living.

Commission: If a man can live without work, how can you force him to work?

Albu: Tax him, then …

Commission: Then you would not allow the kaffir to hold land in the country, but he must work for the white man to enrich him?

Albu: He must do his part of the work of helping his neighbours.

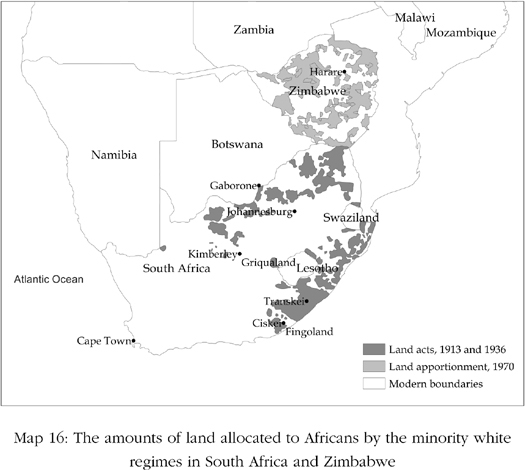

Both of the goals of removing competition with white farmers and developing a large low-wage labor force were simultaneously accomplished by the Natives Land Act of 1913. The act, anticipating Lewis’s notion of dual economy, divided South Africa into two parts, a modern prosperous part and a traditional poor part. Except that the prosperity and poverty were actually being created by the act itself. It stated that 87 percent of the land was to be given to the Europeans, who represented about 20 percent of the population. The remaining 13 percent was to go to the Africans. The Land Act had many predecessors, of course, because gradually Europeans had been confining Africans onto smaller and smaller reserves. But it was the act of 1913 that definitively institutionalized the situation and set the stage for the formation of the South African Apartheid regime, with the white minority having both the political and economic rights and the black majority being excluded from both. The act specified that several land reserves, including the Transkei and the Ciskei, were to become the African “Homelands.” Later these would become known as the Bantustans, another part of the rhetoric of the Apartheid regime in South Africa, since it claimed that the African peoples of Southern Africa were not natives of the area but were descended from the Bantu people who had migrated out of Eastern Nigeria about a thousand years before. They thus had no more—and of course, in practice, less—entitlement to the land than the European settlers.

Map 16 (this page) shows the derisory amount of land allocated to Africans by the 1913 Land Act and its successor in 1936. It also records information from 1970 on the extent of a similar land allocation that took place during the construction of another dual economy in Zimbabwe, which we discuss in chapter 13.

The 1913 legislation also included provisions intended to stop black sharecroppers and squatters from farming on white-owned land in any capacity other than as labor tenants. As the secretary for native affairs explained, “The effect of the act was to put a stop, for the future, to all transactions involving anything in the nature of partnership between Europeans and natives in respect of land or the fruits of land. All new contracts with natives must be contracts of service. Provided there is a bona fide contract of this nature there is nothing to prevent an employer from paying a native in kind, or by the privilege of cultivating a defined piece of ground … But the native cannot pay the master anything for his right to occupy the land.”

To the development economists who visited South Africa in the 1950s and ’60s, when the academic discipline was taking shape and the ideas of Arthur Lewis were spreading, the contrast between these Homelands and the prosperous modern white European economy seemed to be exactly what the dual economy theory was about. The European part of the economy was urban and educated, and used modern technology. The Homelands were poor, rural, and backward; labor there was very unproductive; people, uneducated. It seemed to be the essence of timeless, backward Africa.

Except that the dual economy was not natural or inevitable. It had been created by European colonialism. Yes, the Homelands were poor and technologically backward, and the people were uneducated. But all this was an outcome of government policy, which had forcibly stamped out African economic growth and created the reservoir of cheap, uneducated African labor to be employed in European-controlled mines and lands. After 1913 vast numbers of Africans were evicted from their lands, which were taken over by whites, and crowded into the Homelands, which were too small for them to earn an independent living from. As intended, therefore, they would be forced to look for a living in the white economy, supplying their labor cheaply. As their economic incentives collapsed, the advances that had taken place in the preceding fifty years were all reversed. People gave up their plows and reverted to farming with hoes—that is, if they farmed at all. More often they were just available as cheap labor, which the Homelands had been structured to ensure.

It was not only the economic incentives that were destroyed. The political changes that had started to take place also went into reverse. The power of chiefs and traditional rulers, which had previously been in decline, was strengthened, because part of the project of creating a cheap labor force was to remove private property in land. So the chiefs’ control over land was reaffirmed. These measures reached their apogee in 1951, when the government passed the Bantu Authorities Act. As early as 1940, G. Findlay put his finger right on the issue:

Tribal tenure is a guarantee that the land will never properly be worked and will never really belong to the natives. Cheap labour must have a cheap breeding place, and so it is furnished to the Africans at their own expense.

The dispossession of the African farmers led to their mass impoverishment. It created not only the institutional foundations of a backward economy, but the poor people to stock it.

The available evidence demonstrates the reversal in living standards in the Homelands after the Natives Land Act of 1913. The Transkei and the Ciskei went into a prolonged economic decline. The employment records from the gold mining companies collected by the historian Francis Wilson show that this decline was widespread in the South African economy as a whole. Following the Natives Land Act and other legislation, miners’ wages fell by 30 percent between 1911 and 1921. In 1961, despite relatively steady growth in the South African economy, these wages were still 12 percent lower than they had been in 1911. No wonder that over this period South Africa became the most unequal country in the world.

But even in these circumstances, couldn’t black Africans have made their way in the European, modern economy, started a business, or have become educated and begun a career? The government made sure these things could not happen. No African was allowed to own property or start a business in the European part of the economy—the 87 percent of the land. The Apartheid regime also realized that educated Africans competed with whites rather than supplying cheap labor to the mines and to white-owned agriculture. As early as 1904 a system of job reservation for Europeans was introduced in the mining economy. No African was allowed to be an amalgamator, an assayer, a banksman, a blacksmith, a boiler maker, a brass finisher, a brassmolder, a bricklayer … and the list went on and on, all the way to woodworking machinist. At a stroke, Africans were banned from occupying any skilled job in the mining sector. This was the first incarnation of the famous “colour bar,” one of the several racist inventions of South Africa’s regime. The colour bar was extended to the entire economy in 1926, and lasted until the 1980s. It is not surprising that black Africans were uneducated; the South African state not only removed the possibility of Africans benefiting economically from an education but also refused to invest in black schools and discouraged black education. This policy reached its peak in the 1950s, when, under the leadership of Hendrik Verwoerd, one of the architects of the Apartheid regime that would last until 1994, the government passed the Bantu Education Act. The philosophy behind this act was bluntly spelled out by Verwoerd himself in a speech in 1954:

The Bantu must be guided to serve his own community in all respects. There is no place for him in the European community above the level of certain forms of labour … For that reason it is to no avail to him to receive a training which has as its aim absorption in the European community while he cannot and will not be absorbed there.

Naturally, the type of dual economy articulated in Verwoerd’s speech is rather different from Lewis’s dual economy theory. In South Africa the dual economy was not an inevitable outcome of the process of development. It was created by the state. In South Africa there was to be no seamless movement of poor people from the backward to the modern sector as the economy developed. On the contrary, the success of the modern sector relied on the existence of the backward sector, which enabled white employers to make huge profits by paying very low wages to black unskilled workers. In South Africa there would not be a process of the unskilled workers from the traditional sector gradually becoming educated and skilled, as Lewis’s approach envisaged. In fact, the black workers were purposefully kept unskilled and were barred from high-skill occupations so that skilled white workers would not face competition and could enjoy high wages. In South Africa black Africans were indeed “trapped” in the traditional economy, in the Homelands. But this was not the problem of development that growth would make good. The Homelands were what enabled the development of the white economy.

It should also be no surprise that the type of economic development that white South Africa was achieving was ultimately limited, being based on extractive institutions the whites had built to exploit the blacks. South African whites had property rights, they invested in education, and they were able to extract gold and diamonds and sell them profitably in the world market. But over 80 percent of the South African population was marginalized and excluded from the great majority of desirable economic activities. Blacks could not use their talents; they could not become skilled workers, businessmen, entrepreneurs, engineers, or scientists. Economic institutions were extractive; whites became rich by extracting from blacks. Indeed, white South Africans shared the living standards of people of Western European countries, while black South Africans were scarcely richer than those in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. This economic growth without creative destruction, from which only the whites benefited, continued as long as revenues from gold and diamonds increased. By the 1970s, however, the economy had stopped growing.

And it will again be no surprise that this set of extractive economic institutions was built on foundations laid by a set of highly extractive political institutions. Before its overthrow in 1994, the South African political system vested all power in whites, who were the only ones allowed to vote and run for office. Whites dominated the police force, the military, and all political institutions. These institutions were structured under the military domination of white settlers. At the time of the foundation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the Afrikaner polities of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal had explicit racial franchises, barring blacks completely from political participation. Natal and the Cape Colony allowed blacks to vote if they had sufficient property, which typically they did not. The status quo of Natal and the Cape Colony was kept in 1910, but by the 1930s, blacks had been explicitly disenfranchised everywhere in South Africa.

The dual economy of South Africa did come to an end in 1994. But not because of the reasons that Sir Arthur Lewis theorized about. It was not the natural course of economic development that ended the color bar and the Homelands. Black South Africans protested and rose up against the regime that did not recognize their basic rights and did not share the gains of economic growth with them. After the Soweto uprising of 1976, the protests became more organized and stronger, ultimately bringing down the Apartheid state. It was the empowerment of blacks who managed to organize and rise up that ultimately ended South Africa’s dual economy in the same way that South African whites’ political force had created it in the first place.

DEVELOPMENT REVERSED

World inequality today exists because during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries some nations were able to take advantage of the Industrial Revolution and the technologies and methods of organization that it brought while others were unable to do so. Technological change is only one of the engines of prosperity, but it is perhaps the most critical one. The countries that did not take advantage of new technologies did not benefit from the other engines of prosperity, either. As we have shown in this and the previous chapter, this failure was due to their extractive institutions, either a consequence of the persistence of their absolutist regimes or because they lacked centralized states. But this chapter has also shown that in several instances the extractive institutions that underpinned the poverty of these nations were imposed, or at the very least further strengthened, by the very same process that fueled European growth: European commercial and colonial expansion. In fact, the profitability of European colonial empires was often built on the destruction of independent polities and indigenous economies around the world, or on the creation of extractive institutions essentially from the ground up, as in the Caribbean islands, where, following the almost total collapse of the native populations, Europeans imported African slaves and set up plantation systems.

We will never know what the trajectories of independent city-states such as those in the Banda Islands, in Aceh, or in Burma (Myanmar) would have been without the European intervention. They may have had their own indigenous Glorious Revolution or slowly moved toward more inclusive political and economic institutions based on growing trade in spices and other valuable commodities. But this possibility was removed by the expansion of the Dutch East India Company. The company stamped out any hope of indigenous development in the Banda Islands by carrying out its genocide. Its threat also made the city-states in many other parts of Southeast Asia pull back from commerce.

The story of one of the oldest civilizations in Asia, India, is similar, though the reversing of development was done not by the Dutch but by the British. India was the largest producer and exporter of textiles in the world in the eighteenth century. Indian calicoes and muslins flooded the European markets and were traded throughout Asia and even eastern Africa. The main agent that carried them to the British Isles was the English East India Company. Founded in 1600, two years before its Dutch version, the English East India Company spent the seventeenth century trying to establish a monopoly on the valuable exports from India. It had to compete with the Portuguese, who had bases in Goa, Chittagong, and Bombay, and the French with bases at Pondicherry, Chandernagore, Yanam, and Karaikal. Worse still for the East India Company was the Glorious Revolution, as we saw in chapter 7. The monopoly of the East India Company had been granted by the Stuart kings and was immediately challenged after 1688, and even abolished for over a decade. The loss of power was significant, as we saw earlier (this page-this page), because British textile producers were able to induce Parliament to ban the import of calicoes, the East India Company’s most profitable item of trade. In the eighteenth century, under the leadership of Robert Clive, the East India Company switched strategies and began to develop a continental empire. At the time, India was split into many competing polities, though many were still nominally under the control of the Mughal emperor in Delhi. The East India Company first expanded in Bengal in the east, vanquishing the local powers at the battles of Plassey in 1757 and Buxar in 1764. The East India Company looted local wealth and took over, and perhaps even intensified, the extractive taxation institutions of the Mughal rulers of India. This expansion coincided with the massive contraction of the Indian textile industry, since, after all, there was no longer a market for these goods in Britain. The contraction went along with de-urbanization and increased poverty. It initiated a long period of reversed development in India. Soon, instead of producing textiles, Indians were buying them from Britain and growing opium for the East India Company to sell in China.

The Atlantic slave trade repeated the same pattern in Africa, even if starting from less developed conditions than in Southeast Asia and India. Many African states were turned into war machines intent on capturing and selling slaves to Europeans. As conflict between different polities and states grew into continuous warfare, state institutions, which in many cases had not yet achieved much political centralization in any case, crumbled in large parts of Africa, paving the way for persistent extractive institutions and the failed states of today that we will study later. In a few parts of Africa that escaped the slave trade, such as South Africa, Europeans imposed a different set of institutions, this time designed to create a reservoir of cheap labor for their mines and farms. The South African state created a dual economy, preventing 80 percent of the population from taking part in skilled occupations, commercial farming, and entrepreneurship. All this not only explains why industrialization passed by large parts of the world but also encapsulates how economic development may sometimes feed on, and even create, the underdevelopment in some other part of the domestic or the world economy.