Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 8. The Death Penalty Commission

THE CONCERN WITH SUFFERING that characterized the death penalty debates was a relatively new phenomenon. For most of human history violence and pain had been unremarkable aspects of everyday life. In premodern societies minor insults led easily to duels or fistfights, which regularly escalated into bloody feuds and vendettas. In medieval England homicide was as common among noblemen as among peasants, producing a murder rate twice as high as in the modern United States. Many of those who did not succumb to violence fell victim to accident and disease: Women died during childbirth; illness routinely felled infants and children; men were maimed and killed in warfare and farm accidents; plague and famine killed indiscriminately. Pain provided the texture of everyday life, and people accepted it as inevitable. Christians saw it as punishment for sin, or even as on opportunity to draw closer to the divine by sharing the suffering of Christ. Physical suffering was routine, and compassion was a precious resource, easily exhausted and grudgingly dispensed.1

By the end of the nineteenth century the situation had changed. William James, the great psychologist and brother to Henry, noted in 1901 that in the past century a "moral transformation" had "swept over our Western world. We no longer think that we are called on to face physical pain with equanimity." Compassion was now extended to all of humanity, and cruelty became the worst of sins. An 1891 advertisement for a laxative expressed the new mood in rhyme: "What higher aim can man attain than conquest over human pain?"2

The intellectual origins of this revolution in human feeling lay in the late seventeenth century, when Anglican clerics, rejecting both the angry God of the Puritans and Thomas Hobbes's dark view of human nature, redefined God as benevolent and human nature as intrinsically compassionate. Inspired by these attitudes, a generation of writers—the philosopher Francis Hutcheson, novelists Sarah Fielding and Samuel Richardson—gave birth to a "humanitarian sensibility" and spread the gospel that cruelty was repugnant and sympathy the highest human emotion. The word civilization arose alongside the humanitarian sensibility and was tightly bound with it. Those who inflicted pain were "barbarous"; those who did not were "civilized." People widened their circle of sympathy to embrace not only family members and fellow villagers but a broad swath of humanity. Practices that had been unquestioned for centuries—child labor, slavery, torture, bull-baiting—came to be criticized as heartlessly cruel. The U.S. Constitution's prohibition of "cruel and unusual punishments" was an expression of this compassionate sensibility, as was the decision by many states to limit the number of crimes punishable by death.3

This way of thinking was restricted to the upper classes of England and America in the years before the American Revolution. In the nineteenth century the middle classes embraced humanitarianism as a sign of respectability and applied it to a wide range of social reforms. Some of the first targets were the miserable conditions in the slums of industrializing cities. Massachusetts, the first American state to industrialize, enacted its first laws regulating child labor in 1842. Other humanitarian reforms included the education of the blind and deaf, treatment of the mentally ill, public health measures, and better housing for the poor. The most famous and most significant movement was abolition, undertaken in part out of sympathy with slaves. These were complex movements driven by many motivations, but the desire to decrease the measure of human suffering was prominent among them.4

Nothing better illustrates the revulsion at pain than the discovery and lightning-quick adoption of medical anesthesia. Surgery before anesthesia was an exercise in torture. Doctors, like orthodox Christians, traditionally viewed pain as inevitable, or even as a necessary part of the healing process. But as fear of suffering grew, fewer doctors found this attitude viable. In 1846, a Boston dentist demonstrated that ether gas could prevent the pain of surgery. Within a few years doctors discovered that chloroform and nitrous oxide produced similar effects. Some doctors resisted because of the health risks of anesthesia, or because they continued to believe that suffering was good for the patient. Most, though, were thrilled to have a way to ease their patients' suffering. No medical discovery had ever gained general acceptance so quickly. Anesthesia both reflected and reinforced the culture's aversion to pam—now that it could be relieved, it became even more repugnant.5

Not only humans benefited from the humanitarian sensibility. In 1866 Henry Bergh, the wayward and wealthy heir to a shipbuilding fortune, founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The names of the men who assisted Bergh with the project—John Jacob Astor Jr., Horace Greeley, Peter Cooper, Ezra Cornell-indicated the social constituency of the cause. Bergh's organization was modeled after the Royal SPCA in London, but the American humane movement soon outstripped its British counterpart. SPCAs were established in Philadelphia, Boston, Buffalo, and other cities. The societies had the power to bring legal action against animal abusers, but their primary mission was not prosecutory but pedagogic: teaching people, especially children, that it was wrong to make animals suffer.6

The SPCA drew its membership almost entirely from the upper and middle classes, and there was good reason for this. The poor—trapped in the lethal squalor of industrial America, working jobs with high fatality rates—lived lives of premodern brutality and therefore assigned a low priority to the suffering of animals. Faced with a daughter who had lost her arm in a textile factory, who cared about a cart driver beating his horse? Members of the SPCA considered this indifference to animal cruelty as unfortunate for animals and dangerous to society.

Humanitarians railed against a common game—known as "spinning the cockchafer"—in which children pinned a beetle to the end of a string and spun it in the air so they could enjoy the loud whirring noises it made. Reformers objected not out of sympathy with the animal's suffering but because they saw it as the first step down the slippery slope of cruelty. What started with beetles would then lead to dogs, and to people: "Cruelty to animals predisposes us to acts of cruelty towards our own species," ASPCA founder Henry Bergh explained. In 1870 the Pennsylvania SPCA noted two cases in which men arrested for cruelty to animals later committed murder. In an SPCA journal, an illustration titled "The Labor Problem" showed a factory in flames and the arsonist, a union man, shot dead by a militia. The caption read, "Shall it be this—or humane education of rich and poor?" The humane movement was as much about taming the lower orders as about protecting animals. In the peculiar vision of some anticruelty reformers, social problems sprang not from vicious exploitation of the poor but from torturing beetles or kicking dogs. SPCAs lobbied hardest against the cruelties that were most public—especially the beating of carriage horses—because such spectacles "tend to brutalise a thickly crowded population."7

This same fear—of the contagiousness of cruelty—motivated much of the opposition to hanging. Executions whipped spectators into such a frenzy that they committed violent crimes themselves. It was reported, for example, that a man who attended Jesse Strang's 1827 hanging in Albany committed murder eleven days later. Hanging produced a "demoralizing effect upon society," one writer said. "We would put an end to capital punishment, for the sake of the law-abiding classes; just as the abolition of Slavery was wisely urged for the benefit of the white man." The statement reveals the self-interest that often lay at the heart of humanitarian sentiment. Reformers were concerned less with the suffering of victims than with the social consequences of that suffering. Spectacles of cruelty—the whipped slave, the beaten horse, the man dangling at the end of a rope—were thought to produce yet more acts of cruelty.8

Although a few citizens cited the suffering of hanged men as an argument in favor of abolishing the death penalty, not many were willing to take this step. Supporters of capital punishment, however, were not untouched by the anticruelty movement; they wanted to achieve the goals of the death penalty without fraying the moral fabric of society. According to one capital punishment advocate, a painless execution method would "deprive those who have the bad manners to argue against the death penalty, of one suggestion by which they operate on the nerves of others."9

THE PIONEERS IN THE FIELD of scientific killing were individuals connected to anticruelty societies. In the 1850s Benjamin Ward Richardson, a distinguished British physician and expert in anesthesia, constructed a "lethal chamber" for killing unwanted animals with carbon monoxide, and for the next thirty years he advocated this method of "humane destruction." In 1874 t n e Pennsylvania SPCA built a special brick room for killing dogs with carbon monoxide, becoming the first American organization to move beyond shooting and drowning as methods of killing unwanted animals. Instructions for building a lethal chamber were published in Popular Science Monthly.10

Soon after the Pennsylvania SPCA built its lethal chamber, a Philadelphia physician suggested that the same method be used for condemned criminals, because it produced "the easiest and quickest death known to science." This was one of many proposals for making the death penalty more humane. In 1847 a Brooklyn murderer was knocked cold with ether before he was hanged, on the theory that he would then not suffer during the drop. In the 1870s the New York Medico-Legal Society formed the Committee on Substitutes for Hanging and considered carbon monoxide, poisons, the garrote (a brass collar fitted with a screw that was turned until it crushed the spine), and the guillotine, before finally deciding that hanging remained the best option, because it shed no blood and produced death with reasonable certainty. Another physician came to the same conclusion after conducting an experiment on himself He had a friend strangle him near the point of death with a towel and at the same time prick him with a knife so that he could judge his level of sensation. After reviving, the physician reported that he lost consciousness in eighty seconds and felt no discomfort at all—not even from the "knife thrusts he was inflicting upon my hand." He concluded that, even if the neck did not break, hanging was not cruel.11

Despite these reassurances, many argued that science could offer a method more palatable than hanging, and electricity soon became a favored candidate. Benjamin Franklin's killing experiments were well known, as were the 1869 tests on pigeons, rabbits, and frogs by lethal chamber inventor Benjamin Ward Richardson. Also in 1869, a writer in Putnam's Magazine predicted that "with new scientific knowledge, a painless mode of killing may be discovered,—as by an electric shock." Scientific American claimed in 1873 that killing with electricity would be "certain and painless." After interviewing prominent physicians and electricians in 1879, the New York Heraldconcluded that electricity offered a "humane, effective and impressive" method of executing condemned criminals.12

The discussion of electrical execution in the Herald, like the earlier one in Scientific American, mentioned batteries, Leyden jars, and induction coils as sources of electricity. By the early 1880s a more potent generator of electricity had become common: the dynamo.

ALTHOUGH ARC LIGHTING ACCIDENTS had claimed four lives in America by the end of 1882, the only one of those deaths to receive serious scientific attention was that of Lemuel Smith, the man who died after grasping the poles of a dynamo in the Buffalo Brush lighting plant in August 1881. The morning after the accident, Joseph Fowler, Buffalo's coroner, conducted an autopsy. Smith's lungs were congested with blood, and the blood appeared to be somewhat thinner than usual, but there was no obvious cause of death. If he had not known the circumstances of the case, Dr. Fowler said, he would not have known what killed the man. He was so intrigued by the case that he returned to the morgue for a second autopsy later in the day. After peeling back the skin from Smith's arms and chest, Dr. Fowler discovered the path of the current: a line stretching from shoulder to shoulder, about two or three inches in width, where the flesh was a little darker than the tissue on either side. A force potent enough to fell a man in seconds left only a delicate tracing upon the flesh.13

Alfred Porter Southwick

Reports of the autopsy caught the attention of Alfred Porter Southwick, a Buffalo dentist who had been following the debates on capital punishment and execution methods. After hearing about Smith's death, Southwick began to collect stray dogs and kill them with electric shocks. As a supporter of the death penalty, Southwick wanted to preserve capital punishment by removing the strongest objection to it: the pain it wrought on its victims, and the damage inflicted upon society by the spectacle of suffering. "Civilization, science, and humanity demand a change," he explained.14

Born in Ohio in 1826, Southwick had moved to Buffalo after finishing high school and found work on the steamboats, eventually becoming chief engineer of the Western Transit Company. Restless in that profession, he studied dentistry and opened a practice in 1862. Southwick helped found the state dental society, later becoming its president, and also helped organize the Dental Department at the University of Buffalo, where he taught dental surgery. His one published scientific article was titled "Anatomy and Physiology of Cleft Palate." Southwick's two professions—steamboat engineering, which familiarized him with power production, and dental surgery, which involved the use of anesthesia—provided a background of sorts for the new art of humane killing with electricity.15

Southwick proved to his own satisfaction that electricity provided the most humane method of capital punishment, but he kept the results private for a few years. Then, in a speech early in 1885, New York governor David B. Hill stated that the "present mode of executing criminals by hanging has come down to us from the dark ages" and proposed that science could furnish a "less barbarous" method of execution. In those words, Southwick sensed an opportunity, because he believed that electricity was precisely the method Governor Hill sought. Southwick also had good political connections: His friend Daniel McMillan was a state senator. At Southwick's urging, McMillan introduced a bill in the state legislature to create a commission to investigate "the most humane and approved method" of execution. The bill, which passed the state legislature and became law in 1886, named three men to the commission, and one of them was Alfred Southwick.16

Southwick's fellow commissioners were Matthew Hale and Elbridge T. Gerry. Hale was an obscure Albany lawyer, but Gerry-chairman of the commission—was a man of note. The grandson and namesake of a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Gerry moved in the highest circles of New York society. At the time of his appointment to the death penalty commission, he was commodore of the New York Yacht Club, and he was also a famous philanthropist. Gerry served as legal counsel to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and in 1874 he had founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, the first organization of its kind in the world. He made frequent appearances in the pages of New York newspapers, presiding over regattas in Newport and staging raids on theaters employing child actors. Gerry was widely recognized as a humanitarian, and his presence on the panel lent considerable weight to the inquiry.17

Elbridge T. Gerry

The commissioners began their work by sending a circular to attorneys, physicians, and public officials, requesting their opinions on capital punishment. Elbridge Gerry hired a staff of nine assistants and set them to work in his private law library, poring over historical and legal books for information about execution methods.18

Southwick, meanwhile, had an opportunity to conduct further experiments. In the summer of 1887 packs of dogs roamed the streets of Buffalo, and the city council fixed a bounty of twenty-five cents for each stray brought to the pound. Local boys, quick to spot a business opportunity, rounded up dogs by the dozen and deposited them at the pound, which became overwhelmed. Concerned about the animals' welfare, the local chapter of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals assumed operation of the pound, including the destruction of unwanted animals. The usual method, shooting, was rejected as cruel. The society instead tried asphyxiating the dogs in a carbon monoxide lethal chamber, but that proved unreliable.19

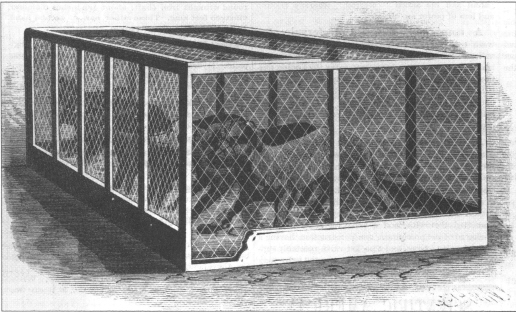

The SPCA then discovered that a citizen of Buffalo was already adept at dog killing and would be happy to share his expertise. On July 16 Alfred Southwick and a friend, the Buffalo physician George Fell, constructed a pine box, lined it with a zinc plate, and filled it with an inch of water. They ran an electrical line from the nearest arc light cable, connecting one pole to the zinc plate, the other to a muzzle with a metal bit. A small terrier was fitted with the muzzle and led into the box. The Morning Express reported what happened next: "A simple touch of a lever—a corpse." Twenty-seven more dogs followed. At its next meeting the SPCA reported that the dogs died "instantly and seemingly without pain" and urged that all unwanted dogs be destroyed with electricity.20

A Scientific American illustration of Southwick and Fell's dog-killing cage, used in Buffalo in the summer of 1887.

THE DEATH PENALTY commissioners completed their work in January 1888 and submitted a report to the New York legislature. Although the report did, at the end, propose a new method of capital punishment, the bulk of it was devoted to a catalog of death, in which the commissioners described—in alphabetical order and exquisite detail—every method of execution they had discovered.

Southwick and his colleagues began with auto da fe (literally "act of faith," the Spanish Inquisition's ceremonial execution of heretics, usually by burning), then proceeded to beating with clubs and beheading, duly noting national differences in decapitation practice among the English, Chinese, and Japanese. Next came blowing from a cannon, in which the victim was either lashed to the cannon's mouth or stuffed into the barrel: "Here is no interval for suffering," the report stated, because "no sooner has the peripheral sensation reached the central perceptive organ than that organ is dissipated on the four winds of heaven." Executions by boiling employed not only water but also melted sulfur, lead, and oil. Breaking on the wheel, in which the victim was lashed to a large wheel and beaten viciously with clubs, was common for a time in western Europe (a blow to the head that brought death and ended suffering was known as a coup de grace—"stroke of mercy"). Death by burning was familiar to students of European history, but the commissioners did not content themselves with such pedestrian examples. They discovered a Persian practice known as "illuminated body," in which the victim was bound to a slab and "innumerable little holes were bored all over his body. These were filled with oil, a little taper was set in each hole and they were all lighted together."

The death commission's report marched on, through burying alive, crucifixion, decimation, dichotomy (splitting the body in two), dismemberment, drowning, exposure to wild beasts (in some cases a victim was sewn "in a sack alive, venomous serpents with him, and sometimes a dog, a monkey or the like were added"), flaying alive, flogging, gar rote, guillotine, hanging, hara-kiri, impalement, iron maiden, poisoning, pounding in mortar, precipitation (throwing the victim off a cliff), pressing to death, the rack, running the gauntlet, shooting, stabbing, stoning, strangling, and suffocation.21

The commissioners were aware that there was something strange about their exhaustive inventory of death. They explained apologetically that "brief mention of these monstrosities" was included to "indicate the thoroughness of the research." But the descriptions were not brief, and they indicated more than the researchers' desire to display their industriousness. In part, the commissioners hoped that compared to such barbarism, their own mercy would shine all the brighter.22

The catalog of death also revealed the dark underbelly of the humanitarian sensibility. During the same years that pain became unacceptable, the public grew more fascinated with violence and death. Edgar Allan Poe was only the most famous of hundreds of nineteenth-century writers who dwelled with delight on blood, murder, dissection, and the putrefying corpse. At dime museums, catchall repositories of nineteenth-century popular culture, the public could see waxwork reproductions of famous murder scenes and jars containing body parts of executed murderers. The anticruelty movement may have curtailed public executions and blood sports, but it only fed the public's appetite for violent death. Horror writing had not existed in the premodern world, when physical torment was an accepted part of everyday life. But when suffering became obscene, the stage was set for a pornography of pain.23

The death commissioners made great efforts to present themselves as thoroughly rational, but they had ventured into territory not easily reducible to the cold logic of science. In their efforts to make executions more civilized, the commissioners found themselves pushed and tugged by the dark allure of violent death.

IN THE SURVEY they sent out as part of their research, the commissioners had asked judges, district attorneys, sheriffs, and a number of physicians to comment on three methods of execution currently in use in "civilized" nations—hanging, guillotine, and garrote—and two novel ones, electricity and poison. Of those who replied, eight supported poison, five the guillotine, four the garrote. Eighty wanted to retain hanging. According to the commissioners, "eighty-seven were either decidedly in favor of electricity, or in favor of it if any change was made." This vague phrase left it unclear how many of those eighty-seven actually preferred hanging to electricity.24

But Southwick and his colleagues were not holding a referendum; they were marshaling evidence to buttress their own recommendation. Although the survey revealed that hanging had many defenders, the commissioners did not seriously consider retaining the gallows. They noted that the public disapproved of hanging female prisoners, which led to obviously guilty women being acquitted by juries or pardoned by governors. The commissioners asserted (without evidence) that people objected "not so much to the execution of women as to the hanging of women," and therefore would embrace killing women by some other method. The commissioners also recounted many instances of bungled hangings, involving broken ropes, faulty trapdoors, slow strangulations, and decapitations. Considering these problems, the commissioners believed that support for the gallows was a product of blind conservatism and could therefore be discounted.25

The report revealed that there were issues at stake besides pain. Carbon monoxide, the method of choice for some SPCAs, was not considered because death from the gas, while painless, could take several minutes. Anxious to avoid a prolonged killing process, which they associated with torture, the commissioners insisted that the death be "instantaneous." They rejected the spine-crushing garrote because it was too slow and because it disfigured the body. The mutilation complaint disqualified the guillotine as well. The French—who as late as the 1780s occasionally burned criminals at the stake and broke them on the wheel—had adopted the guillotine as a humanitarian gesture. New York's death penalty commissioners conceded that the method was quick and painless, but they objected to the blood.* Considering "the fatal chop, the raw neck, the spouting blood," such executions "cannot fail to generate a love of bloodshed among those who witness them." Given that the awful details would be "presented to the public in the journals of the week," the harmful effects would spread throughout society.26

The problem was not so much the suffering of the condemned, the commissioners explained, but the bloody spectacle. Like the SPCA leaders who focused first on public cruelties, the death commissioners wanted to protect the public from the brutalizing spectacle of suffering. Their task, then, was double: to find a painless death, and an unspectacular one.

Rejecting hanging, guillotine, and garrote, the commissioners were left with two options: poison and electricity. Poison advocates recommended a hypodermic injection of prussic acid (a form of cyanide) or morphine. Critics claimed that poisons were an unreliable form of killing, because people differed in their reactions to them. Also, the hypodermic syringe was a relatively new tool in medical practice, and physicians feared that using it for executions would create a prejudice against it "among the ignorant."27

That left electricity. The commission report contained a lengthy description by Dr. George Fell of the electrical dog killings he and Southwick had conducted for the Buffalo SPCA in the summer of 1887. The commissioners quoted from electrical experts who were familiar with accidental deaths from electricity and printed excerpts from survey responses that were in favor of electrical executions. The commissioners concluded by recommending electrical executions, explaining that they would be "instantaneous and painless" and "devoid of all barbarism."28

The unanimous conclusion of the report masked a furious debate that took place behind the scenes. Alfred Southwick had favored electricity from the start, and fairly early on he convinced Matthew Hale to support it as well. But Elbridge Gerry—the most famous and well-respected man on the panel—believed that an injection of morphine would be the most humane method. Without Gerry's support, electricity did not stand a chance. At the last moment, however, he abandoned his preference for poison and came out in favor of electrical execution.29

It was not Alfred Southwick who changed Gerry's mind. On December 19, 1887, just a few weeks before the commission issued its report, Thomas Edison wrote a letter to the commission advocating electrical execution. Edison's opinion shifted Gerry's vote from morphine to electricity. The great inventor was an "oracle," Gerry later explained. "I certainly had no doubt after hearing his statement."30

*Southwick had changed his mind about the painlessness of the guillotine. A year before the report was issued, he told a newspaper reporter that "the guillotine is a barbarous mode of execution. Death does not ensue instantly, as it should in such cases. In fact, a condemned man and I can agree upon certain eye and mouth signals before his head is laid on the block, and I can communicate intelligently with the severed head for some time after the execution by means of such signals."