Gothic Cathedrals: A Guide to the History, Places, Art, and Symbolism (2015)

CHAPTER 9

“ON THE ROAD”

Medieval Journeys—Sacred Pilgrimage and Secular Travel

“All of us are pilgrims on this earth. I have even heard it said that the earth itself is a pilgrim in the heavens”

—Maxim Gorky, The Lower Depths (1)

What was “pilgrimage” really all about in medieval times? People traveled far more than we may realize today, and for many different reasons. “On the road” one might encounter groups of devout pilgrims, penitents on a forced pilgrimage, merchants with their latest products to trade, friars, a lone hermit, troubadours, peasants with highly valued produce or crafts, a king or queen with an entourage, jugglers, messengers, bishops, clergy, knights, monks, craftsmen on their way to a fair or town center, lay preachers, bandits, con artists, and more. The variety was endless.

Far from merely booking a short break away or a longer tourist-related journey, as many tend to perceive of travel today, medieval pilgrimage was meant to be another kind of travel altogether. For pilgrims, it was a special journey in one sense and an adventurous odyssey on the other. This was definitely understood at the time. While pilgrims were required by the Church to make the pilgrimage—in spite of many hardships endured on the road—there were often moments of joy along the way, as Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and other travel accounts reveal. Others were not so lucky; they may have died or been attacked or murdered by bandits. Not all travel had an exclusively sacred focus, obviously, as many in medieval times also journeyed for secular purposes.

Taking a pilgrimage to Compostela, Constantinople, Rome, Jerusalem and other medieval cathedral shrines was a real commitment and expense, and called for much sacrifice—from whatever level of society one came. As it was very costly to go on one of these great long distance pilgrimages, people often chose to visit shrines closer to home. Some of the more popular medieval choices were the tomb of Thomas Becket at Canterbury, the shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham, the shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne, shrines and relics relating to Mary Magdalene in France, and others. Nearly every region had a major shrine of one type of another.

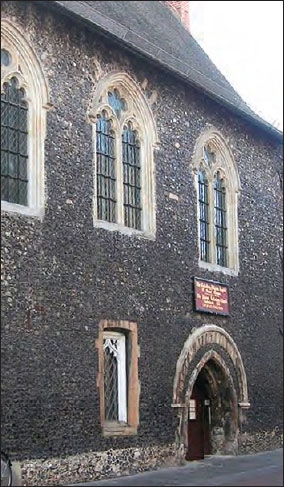

St Thomas Hospice, Canterbury England. The circular arch over the door suggests that the origins of the building are Norman, but much of the structure including the present doorway and upper windows are from 1290-1320. The small lower window has somewhat later tracery. The building still functions as a hospice for the elderly. The upper windows give light into the chapel. The glass appears to be all restoration. (T. Taylor, WMC)

No one was immune from the treacheries of the road—king or peasant—yet, no one was excluded from the often long hoped-for divine blessing, dream, healing, or miracle that might be bestowed upon them at a shrine. Many destinations were in major Gothic cathedrals. At the same time, a number of abbeys, churches, and monasteries had shrines or relics that were closed to the public.

What was a “pilgrimage”

Pilgrimage was a major part of medieval life and was actively encouraged by the Church. Such “journeys of faith” could take men and women thousands of miles from home, friends, and family, and last for months at a time. Short distance pilgrimage could be a spontaneous activity and it was popular at all levels of society. From Chaucer's Canterbury Tales to the later seventeenth century tale Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan, various images of medieval pilgrimage have become known to us. But what do the records indicate? And what was it truly like?

Pilgrimage in Spain via the Via Podiensis trail

Pilgrimage is still a key part of our image of life in the Middle Ages. But it certainly did not start in medieval times. As we know, over the centuries, a number of faiths and spiritual organizations and communities have long had pilgrimage customs and traditions. There is evidence showing that Christian pilgrims were traveling to the Holy Land as early as the third century—long before the High Middle Ages. Various scriptural references were cited about pilgrimage, such as Hebrews 11:13-16, where Paul referred to man's status on earth as that of “a stranger” and “a pilgrim.” In accordance with Christian theological belief in general, importance was placed on the idea of enduring this life in order to secure a better life in the hereafter.

To a devout medieval pilgrim, Man's existence here on earth was seen as temporary anyway, so many pilgrims saw themselves as a “pious guest”—here only for the time being—before he was “called away” by God to a final resting place, Heaven. Even Christ himself has been envisaged as a pilgrim or traveler by painters and other visual artists. One example is in the Church of Santo Domingo de Silos, on the famous road to Compostela. Various ancient, biblical and apocryphal stories were used to support the idea of going on a pilgrimage, such as the account of the arduous trek endured for many years by the Israelites in the Exodus from Egypt to the Promised Land, and other tales.

The whole idea of taking a pilgrimage to a holy place or shrine was natural enough to the medieval mind, and expanded exponentially during the Middle Ages. The official view of a pilgrim by the Church was as the peregrinus (or pauper) Christi, the exile, an allegorical “poor man of Christ.” While many pious, devout pilgrims viewed themselves that way, we will see that certainly not all did!

“Who” went on pilgrimage?

Other world religions and spiritual traditions, have pilgrimage traditions of various types and focus. But in the case of Christianity, by the latter Middle Ages, there were many different reasons why one could be on pilgrimage. Most people, as required by canon law, took a sacred legal vow in front of others to go on and return from a pilgrimage. This was the common practice. But others were legally ordered to go on penitential pilgrimages as punishment for such crimes as heresy.

Nearly all classes made pilgrimages: including kings and queens, nobles, merchants, troubadours, peasants, jesters, precious cloth, oil, or incense dealers, shipbuilders, money changers, skilled craftsmen and women, wine dealers, and so on. The variety was endless, and when the huge throngs of devout, tired, or raucous pilgrims would finally reach their destination, they descended on any number of sacred sites and shrines.

Motives and purpose

The reasons why someone went on a pilgrimage were many and varied. Some were genuinely sincere and went to obtain sacred healings or spiritual benefits for others as well as themselves; others had pilgrimage imposed on them as mentioned. (2) For many of the voluntary pilgrims, the journey served to satisfy their restlessness, and would have been the only chance to ever be able to travel abroad. While the devout and sincere went for purely religious reasons, others went to drink and carouse, and were often accused of singing “wanton songs,” of desiring little else other than to find new sexual partners and indulge in various vices. Musicians and dancers on pilgrimage were often blamed for creating a “too-jovial” atmosphere, to the chagrin of the Church.

The more relaxed attitude to pilgrimage is revealed in the rather amusing memoirs of Arnold von Harff, a well-traveled, fifteenth century pilgrim. He advises of many joys and trials on the road, but also informs his readers of his rather candid list of useful phrases, such as, “Madam, shall I marry you?” and so on. Some women had an equally cavalier attitude towards pilgrimage, as depicted by Chaucer's witty Wife of Bath. (3) However, these later fifteenth century accounts exist mainly after the “great age of pilgrimage” during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Non-religious factors affected pilgrimage numbers as well, such as during the tragic period of the Black Death, or when major changes in the economy were taking place, which affected nearly everyone. Medieval pilgrimage meant different things to different people.

There was some debate, even at its peak, when taking a sacred pilgrimage was at its height, about the overall value of taking a pilgrimage—even within the Church itself. For instance, the thirteenth century Franciscan preacher, Berthold of Regensberg, pointed out that perhaps the funds many pilgrims used for traveling could, in fact, be put to better use closer to home. Later, Erasmus also took a similar view in his fifteenth century work, Rash Vows, where the following rather cynical exchange is reported between a returning pilgrim named Arnold and his friend Cornelius who had never been on pilgrimage:

Cornelius: “You don't return holier?” [from Jerusalem]

Arnold: “Oh, no: worse in every respect.”

Cornelius: “Richer, then?”

Arnold: “No - purse emptier than an old snakeskin.” (4)

The famous medieval diary of the pilgrimage experiences of Margery Kempe shows the rather great divide that existed between those pilgrims who were genuinely sincere about going on a religious pilgrimage—as she was—and those who were merely along “for the ride”—for adventure and to carouse. She vividly describes life on a medieval pilgrimage, offering her first-hand fifteenth century account on what “life on the road” was like. She describes being taunted for her orthodox piety and for praying; she was stolen from on a number of occasions; she risked disease and violence in some inns and hostels. At one point, she was abandoned by her exasperated colleagues, who had apparently gotten tired of her fervent sobbing at certain shrines and left her alongside the road without a guide. This was a very dangerous situation for anyone, let alone an older lady, the mother of fourteen children, traveling by herself. We learn that in spite of it all, she was discovered by another band of pilgrims coming along the way. They were horrified to learn she had been ruthlessly abandoned and accepted her into their company.

For obvious reasons, most pilgrims (male or female) chose to travel in larger groups as the highways and byways were dangerous for anyone. But a fair number also traveled alone. Sometimes a solitary traveler would get from one “leg” of the journey to another, or one hospice to another, and join up with other pilgrims there. As might be expected, it was more complicated for a female pilgrim, who would encounter difficult and disrespectful behavior along the way and, especially, in certain inns or hostels.

The main purpose of a medieval religious pilgrimage reflected medieval religious society at the time—its purpose was for the seeking of union between one's soul and God. Another was paying respect at the shrine of a saint or other venerated religious figure, to whom one would pray for a miraculous cure for oneself or a loved one. (5) A touching love letter in 1484 by devoted wife Margaret Paston to her husband who was away, tenderly reveals that: “When I heard you were ill, I decided to go on pilgrimage to Walsingham ... for you.” (6) Pilgrims also sought to be granted indulgences for visiting certain shrines. Because it was a legal requirement by canon law to make a sacred pilgrimage at some point in one's life, if one was able, pilgrims had to visit certain shrines before returning home and get the documentation to prove they had been there—or else they might risk getting into trouble with Church authorities later. Some well-traveled pilgrims had a number of indulgences they collected along the way, as well as the famed pilgrim's badges for their hats, to show they had truly been there—all symbolic “credits” or evident that they had made the journey. It wasn't long before the lead pilgrimage badges for the major shrines became akin to the more official status of a passport “stamp” today.

Especially by the late medieval period, travel had increased much in general; some pilgrims and travelers who had fulfilled their obligatory pilgrimage requirement, would also opt go on other voluntary trips of their own. By the time of the Renaissance—the mid-fifteenth century onwards—travel, trade, and opportunity increased all the more, resulting in an even greater exchange of knowledge, techniques, teachings, and so on. The famed journeys across Europe of the physician, alchemist, and esoteric philosopher Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, better known as Paracelsus (1493-1541) is a case in point of one well-traveled 15th-16th century researcher. (7)

Saint Peters Basilica, Rome (Peter J St B Green, WMC)

Who could not—or would not—go?

The medieval Church had policies and laws about the requirement to go on a pilgrimage, and most people opted to go at least once in their lives. Those choosing to not go on pilgrimage—with very good reasons—could still benefit from pilgrimages' virtues by offering hospitality and charity to other pilgrims if they happened to be passing through one's region. Examples of those who could not go on a pilgrimage included the elderly, the infirm, or the extremely ill. By offering hospitality or food to pilgrims, one would participate in the ancient idea that you may never know for sure exactly “who” a stranger might truly be. The belief was that a beggar or pilgrim could be an angel, Christ, or a saint in disguise to test your faith and motives. Acts of charity were to be rewarded by the laws of God.

If one were wealthy, one could opt to pay someone else to go on pilgrimage as a “stand in”—a real luxury. There is an example of a 1352 London merchant who is on record as paying a man £20 to go on a pilgrimage to Mount Sinai on his behalf—a large sum at the time.

Pilgrimage as “penance”

Some people were sentenced to make a compulsory pilgrimage. He or she was required to first take an oath before the authorities, swearing to “purge himself” of his sins or heresies, and was then given a document called a safe-conduct. This listed the specific details of his crime. It had to be shown—and stamped—by the religious authorities at the various shrines to which he was ordered to present himself along the route and at his final destination. (8) There he had to again report to the authorities and show them this document before making way to the shrine to make his offering and beg for pardon.

Essentially, this was a type of grueling, demeaning, medieval probation system where one was required to report at certain times and places, yet was not actually in prison. People could be required to do a pilgrimage as a result of criminal activities, such as theft, murder, et al, or, in a number of cases, for “heresy.” Some shrines were known to be the preferred destination to send certain types of penitential pilgrims: for example, Rocamadour was often the choice for the Inquisition to send Cathar heretics. Contrary to what we might expect, the overall distance required by the Church for a penitent pilgrim to travel was not according to the severity of his particular crime or sin. On the whole, the entire length of the route was calculated by the expense of the journey and the time required to be spent in expiation for one's sins or crime—which could be lengthy for some infractions. Like all pilgrims, penitents had to pay for their own lodgings at inns or hospices, buy their own food, and bring their own clothing or equipment. (9)

Any pilgrimage was a difficult journey to make. Those for penance were even harder. Yet, in the eyes of the medieval Inquisition or the Church, the penitent pilgrim was considered to have been quite fortunate not to have been burned. Penitential pilgrims faced an unspoken, underlying future threat of burning that was always present. Naturally, one did not want to be caught again, let alone falsely accused of heresy, or any crime. People had to take great care with whom they chose to associate from that point on, and what their activities were.

Such a “marked man” (or woman) would have been required to wear a distinguishing article while on pilgrimage so everyone around them would automatically be able to identify his crime. For instance, religious heretics were often required to wear a black garment with a white cross on the front and the back; those who had committed a crime like murder, bodily injury, or theft might have to wear chains around their necks, arms, or waist. The idea was to attempt to stigmatize and ostracize the penitent vis-à-vis other pilgrims. However, in some cases, it is known that friendships were forged with other pilgrims who were willing to risk talking or associating with the penitent. Once at the shrine, and having shown his safe-conduct document to the authorities, the penitent pilgrim often had to approach a holy site barefoot, or on his knees. Some would be prepared to fast or undertake a vow of silence, or, at times, they carried heavy stones around their necks. (10)

Pilgrims could offer expiation for their sins in a number of ways. Some accounts describe dramatic healings and cleansings at certain shrines. One example from the early twelfth century describes a woman who visited the shrine at the great Basilica of Mary Magdalene at Vezeley. She touchingly made a list of the various sins for which she sought forgiveness, carefully laid it on the altar, and prayed to the Magdalene. It was said her sins were immediately erased.

A similar dramatic situation is recorded for an Italian man. His sins were said to have been “so vile” that even his own bishop refused to absolve him! Instead, he choose to send him on pilgrimage to Santiago, with a long written list of his errors. The author of the Miracles of St. James carefully assures his readers, “it is plain that whoever goes truly penitent to St. James and asks for his help with all his heart, will certainly have all his sins expunged.” (11) In some accounts, rather dramatic miracles are occasionally recorded. One exceptionally pious Aquitanian knight, whom St. Mary Magdalene was said to have raised from the dead in the mid-twelfth century, is described as going on annual pilgrimage in gratitude, to her shrine at Vezelay. (12)

Some penitent pilgrims may have had friends in prison, or were very concerned they might be returned there again. They might therefore also try to visit the shrines of certain Black Madonnas that were especially known for the freeing of prisoners, or, to try to visit the shrines of such patron saints of prisoners as St. Leonard and St. Roch to pray for help, healing, or release from limiting circumstances.

One poignant account of a penitent pilgrim that has survived is of a female Cathar weaver who was sentenced to go on a very long, difficult pilgrimage in the mid-thirteenth century. She was being punished simply for giving two other female Cathar colleagues thread, from which they made head-bands—one of the activities that was expressly forbidden by the Inquisition in the Languedoc. Weavers (in particular) were believed to be heavily infiltrated with Cathar heretics and many female Cathars were described as experts at spinning, weaving, and other skilled crafts. (13)

Pilgrimage might be considered a suitable penance for women, such as those handed out by the Inquisition at Gourdon in Quercy in 1241. Here, as records show, over 90 percent of female penitents were sentenced to go on a penitential pilgrimage, as opposed to 54 percent of men. The men were instead sent away on crusades for their penance. (14)

The table of sentences handed down to various heretics in the region of Dossat by the Languedoc Inquisitor Bernard de Caux covered a four-month period in 1246. It lists 207 sentences in total. Although the guilty were not burned or imprisoned, quite a number were sent on what are described as “compulsory pilgrimages.” The modus operandi of the Inquisitors was insidious. If one were forcibly sent on pilgrimage, the penalty for future infractions was death. The committees of the Inquisition would operate in a community over many decades and so had a long institutional memory. The constant pressure and threat of execution for one's beliefs was ever-persistent, i.e., whether for associating with, providing food or hospitality to, or having anything to do with heretical groups. (15) One woman who had given shelter and hospitality to a Waldensian heretic and provided bread, wine, and nuts to the Cathars was punished by being forced to support a poor person for one year, as well as being sent on a number of pilgrimages. (16)

Catedral de Santiago de Compostella (Mmacbeth, WMC)

“When” did they go?

Pilgrimage was quite expensive. The wealthy pilgrim—royalty, nobles, or the clergy—had many choices. Other pilgrims would choose to make a once-in-a-lifetime journey. Or they might visit shrines on the major feast days closer to home. In their own country, they would have much more leeway, less expense, and less distance to travel.

The major feast days of a particular saint were key times when people were very much hoping to be able to spend a nighttime vigil on the eve of that day at the shrine itself. However, in order to do this, one would have to arrive at least a day or two earlier, show the authorities your “passport,” get it stamped upon entry to that country or region, and then proceed through the huge throngs of other pilgrims making their way to the same shrine. The feast days were the most crowded times of year.

As far as “when” to travel, all pilgrims, rich or poor, had to take into account transport arrangements. These could be quite complicated in medieval times for anyone. If the distant Holy Land or Jerusalem was your final destination, ships left from Venice carrying pilgrims on that particular route only twice a year. So that would determine when you would go.

If Rome was your final call, then there were more options to consider. If leaving from the Continent, like France, it could be rather simple. But there might be long distances to travel by foot. If you were coming from further north, or from England, for instance, and connecting with a ship, advance planning was even more essential. Figuring out which legs of the journey connected where, how much it would cost, and the time involved, all had to be carefully considered. Not all that different from today!

If you were heading for the shrine of St. James at Compostela in northern Spain, for example, then depending on where you were departing from, you might wish to get to one of the major pilgrimage points in France. Pilgrims preferred to gather together there and depart in the safety of large groups. These towns (and their famed cathedrals and shrines) were at Paris/Orleans, Vezeley, Toulouse, and Le Puy. (17)

The main “heyday” of medieval pilgrimage began in the latter part of the twelfth century and continued through the thirteenth. The now-famous images of thousands of pilgrims descending on a cathedral or a shrine occurred during this period. Pilgrimages to major shrines in western Europe were so popular in the thirteenth century, that at one point, the French council took solemn measures to completely forbid pilgrimages to Rome for a time—due to fears of temporary depopulation! (18)

MEDIEVAL TRAVEL IN GENERAL: METHODS

Importance of Venice: seven major shipping routes

Sea travel was often long and unpredictable, with many dangers, bad weather, and delays. Huge double or triple-decked galleys were the usual type of ship, and the captains and owners had to have a license to operate them. Certain ports were the most common departure points. In England, pilgrims would leave by ship from London, Dover, or Plymouth. Depending on where they were ultimately heading—the Holy Land or Constantinople for example—they would likely have to go to another port along the way. (19)

One of the most common continental departure ports was Venice. The savvy Venetian merchants and their powerful fleets controlled much of the sea trade, which included transporting pilgrims. As mentioned earlier, ships generally left twice a year in the direction of the Holy Land. Before the middle of the fifteenth century, Venice was famed for its extensive maritime expertise. Huge ships for transporting all types of goods, exotic spices, and pilgrims were called the “great galleys,” a very important part of the Venetian merchant fleet. Smaller, lighter galleys were used for war and crusades. For centuries, Venice ran seven major “great galley” routes to major ports like Constantinople, Cyprus, Rhodes, Sicily, Valencia, Flanders, Majorca, Andalusia, Portugal, England, Granada, Alexandria, and Greece. (20)

Secular merchant travel: Incense and the spice trade

On many occasions, pilgrims would interact and travel with merchants and others on the way to their final destinations. This was particularly true in the thirteenth century when trade vastly increased due to rapidly growing population. An influx of goods came into western Europe including expensive goods which made up the major part of long distance trade. Products included exotic teas, costly incenses, luxurious silks, spices, precious stones, pearls, medicinal remedies, wines, oils, and so on. Pepper was very highly prized and had high customs duty fees and taxes imposed, as did certain varieties of teas. (21) The medieval money supply was at a peak not to be reached again for several centuries. This naturally increased the demand among royalty and the wealthy for more luxurious items.

There were many facets of medieval trade, money, and the exchange of goods. Among others were the various products of the spice trade, already mentioned—perfumes, ointments, oils, and incenses—as well as fabrics, especially silks, dyes, and other items from the “exotic East.” This resulted in the rather fervent build-up of a kind of folklore of its own, an aura of exclusivity. Unbroken trading contacts were maintained for centuries between the Christian and Islamic worlds; Syrians and Jews in the Eastern territories were held in high regard as doctors, merchants and moneylenders to the medieval trade. (22)

Thousands of Christian communities needed wine for Mass, oil for consecration and unctions, and incense for services and at shrines, so they, too, had contacts and dealings with these networks at various times. The trade between East and West extended over great distances, often more than 4000 miles. Occasionally trading disputes would erupt and monopolies over certain goods or territories would be in conflict. And, of course, smuggling and piracy developed its own underworld.

Monks ... and other smugglers of valued goods

Some rather amusing and historically documented dramas feature members of the Church in their cast of characters. The silk trade was particularly lucrative.

Monks reputedly succeeded in smuggling silk-moth eggs hidden in their staves into Byzantium, where a thriving silk industry soon arose. Willibald, later Bishop of Eichstatt, was endowed with a high degree of native cunning; in 720 he got round an export ban by putting balsam into a vessel and masking its characteristic smell with the stronger smell of petroleum ... (23)

Venice played a key role in medieval trade and grew and became very wealthy from its commerce with the East, particularly Byzantium, the “gateway to the East.” Venetians brought precious oils, perfumes and spices into western Europe as early as the ninth century. Special perfumes, especially musk, were brought to Europe in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries from Arabia. Trade with the Islamic world included merchandise brought back to Europe by returning Crusaders. Romantic stories of exotic spices and exciting adventures from the great medieval travelers such as Marco Polo (1254-1324) continue to fascinate readers. By the thirteenth century, East India, in particular had developed an especially powerful trade network for all sorts of spices, including cloves, nutmeg, as well as its famed teas. (24)

Preparations for a pilgrimage

The first consideration for undertaking a pilgrimage, especially one involving long distances, was setting one's affairs in order. Given the great difficulties on the road or by sea, one knew that he or she might never come back. While this was especially true for traveling merchants and crusaders, records show that many devout pilgrims died during travel. Different measures were undertaken before leaving: paying off one's debts, making a will, giving money or possessions to the poor in one's own community, and so on. Some decided to sell some of their goods to help fund their journey, while others with more resources might choose to put their most valued land deeds, family heirlooms, jewels, et al, in a safe Templar commandery. At any level of society, a pilgrim would set his or her own affairs in order the best he could. Valuable produce, animals, craftsmen's equipment, tools, clothing, and so on could be donated to others, or given to the Church. And, like travelers everywhere, pilgrims were concerned about relevant issues like their overall itinerary, costs of the journey, and accommodations along the way.

One hugely important expectation was for everyone to make amends to those they had wronged before leaving on a pilgrimage. That was viewed as being as important as making one's religious confession—the whole idea was to “set things right” altogether, to clear the decks from one's past before going on a pilgrimage, and to attempt to begin anew. The pilgrimage was ultimately seen as a journey of spiritual transformation.

Dangers from rogues and bandits:

Ever heard the expression “highway robbery”? While we all certainly know of the deeds of pirates by sea, in medieval times, there were also “pirates” on land. Those infamously dubbed “highway robbers” preyed along the roads, highways, and byways within Europe and at the major pilgrimage sites. They were a huge problem for travelers and pilgrims.

Safety in medieval times was never certain for anyone, rich or poor. In the month of September in France, for instance, the precious cloth merchants in Troyes needed at least one strong escort to go over to Chalon. The opening of the fair was often delayed for two weeks or more simply due to security issues. Armed groups lurked along the highways to and from the famous fairs, like those held annually at Troyes or Champagne. Here, we have a candid firsthand account from a real highway robber who was executed for his numerous deeds. He commented about he and his band's adventures, their crafty plans to ambush travelers—the wealthier, the better. As we can see, absolutely anyone along the road was fair game:

There is no time, diversion, gold, silver, or glory in the world that can compare to men at arms battling as we have done in the past. How delighted we were when we rode off on adventures, and we might find In the fields a rich abbot or a rich prior or a rich merchant or a string of mules from Montpellier, Narbonne, Limoux, Fanjeaux, Beziers, Carcasonne, or Toulouse, loaded with cloth of gold or silk, from Brussels or Montivilliers ... or spices coming from Damascus or Alexandria! Everything was ours, or ransomed at our will. Every day we had new money ... And when we rode, the whole country trembled before us; everything was ours, going and coming. (25)

Today, it may be hard for us to imagine the courage required for people to embark on a pilgrimage, whether as the “journey of a lifetime” or for penance. No wonder so many were described as “raucous” or “excitable” upon arriving at their destination—at least they got there safely! Many did not survive. At times the road would be so dangerous that even people traveling in large groups might be attacked. Sometimes, travelers were so desperate they would leave the sick and wounded behind to die so they could keep moving. No one, day or night, even wanted to take the time to bury the dead—as he or she could be next—a sitting duck target for the ever-present bandits lurking in the shadows.

Risk of illness, infestation, and disease:

Among the dangers of travel were catching diseases in strange areas or distant regions; dealing with vermin, fleas, and rats in inns, hospices, or tavern accommodations; and encountering contaminated or rotten food. Especially from the year 1400 on, the very real risk of contracting the bubonic plague grew considerably when on pilgrimage, as one was traveling to unknown places with masses of different people. Numerous accounts indicate that following the 1400 Jubilee year—when even larger numbers of pilgrims were traveling—many began to get ill with the plague. Those traveling through Italy were taken to the famous medieval Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala at Siena on the way to Rome. Here people left their belongings and money with the clergy. Many of course never survived, and their belongings and money remained with the Church.

Stella Maris imagery of Our Lady, depicted here as “the Star of the Sea,” from a hostel sign. (Simon Brighton)

Money / Costs:

If you have ever used TripAdvisor to read accounts of travelers' experiences at bed and breakfasts, hotels, restaurants, or worried about how much a journey might cost, or how high the exchange rate would likely be for changing your currency at your next destination, you can appreciate the concerns of travelers in all times. Medieval pilgrims had exactly the same needs. Consider this: “A late fifteenth-century guide for south German pilgrims to Compostela gave details of both hospices and inns along the way, with comments on the innkeepers and whether their prices were reasonable, as well as the costs of using bridges and when to change currency.” (26)

A case in point: even Gerald of Wales ran out of money on pilgrimage!

Have you ever been traveling abroad and experienced distress when either your bank card didn't work in an ATM in a foreign country, or the insurance or exchange rates were too high at certain times.? Perhaps, you, or someone you know, may have been robbed on a trip, or, simply run out of funds for any number of reasons. Well, you are not alone. Medieval travelers, even prominent ones, encountered similar issues.

One revealing-and-true medieval anecdote about the perils of running out of money on a pilgrimage features the now-famous medieval Arthurian manuscript author Giraldus (Gerald of Wales):

Gerald of Wales ran out of money in Rome in 1203, leaving all his bills unpaid. He attempted to flee, but his creditors pursued him to Bologna, where they demanded payment. No one in Bologna would lend him money unless he could find a local inhabitant to guarantee that he would repay the lender's agent in England. But guarantors were reluctant to step forward. Only a few weeks earlier a number of Spanish students and priests in Bologna had been imprisoned after they had kindly offered security for a compatriot, who had then defaulted. Still followed by his creditors, Gerald continued north until they were finally induced to accept a promissory note drawn on merchants at the Troyes fair. The following year, when Gerald returned to Rome, he called at Troyes and bought bills of exchange worth twenty gold marks of Modena from merchants of Bologna. Even then, he had difficulty in changing them at Faenza. (27)

The trials and tribulations of Gerald's case are not all that unusual for a medieval traveler. Pilgrims constantly encountered wildly changing exchange rates and nasty currency dealers. After the 1312 suppression of the Order of the Temple, other institutions began to get more involved in financial and banking practices. With the development of a more sophisticated banking system in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the life of wealthier travelers became much easier. Hoteliers often acted as bankers. At Toulouse, for instance, hoteliers would lend money, transfer it to the traveler's next destination, guarantee debts, or accept bills of exchange. There was such a great variety of currencies and rates of exchange, that pilgrims and secular, commercial travelers had to be constantly wary. Some today might laugh and say, “well, not much has changed!” Perhaps Gerald was lucky—at least he did get to finally change his money and pay off his creditors in Italy.

Another key medieval pilgrimage writer, William Wey, advised travelers in the 15th century to bring along an ample supply of coins from Tours, Candi, and Modena, as well as Venice—the nearest thing to the internationalcurrency of the Mediterranean at the time. (28)

Safe deposit

Some pilgrims chose to leave their most precious goods in what we would now call a kind of safety deposit box system. Back in the twelfth century, loans to Crusaders were one of the Templar Orders' most common financial transactions. But by the thirteenth century, the Templar empire had grown so extensive and powerful that their loans became a key part of the entire western European financial system. In a dangerous world, Templar commanderies and preceptories throughout Europe were regarded as the safest places for pilgrims, crusaders, or merchant travelers, to securely store valuables like wills, treaties and charters, money, gems, jewels, coins and family heirlooms, before traveling.

This applied to nobles and kings as much as peasants. Everyone at all levels of society preferred to leave their valuables with the Templars. Here they were assured that their goods would be kept safe and in good condition for as long as necessary. Crusaders and pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land in particular, tended to make sure that their earthly affairs were in order before they left, in case they would die or be seriously injured and never return home again. The Templar storerooms were unquestionably the most secure safe deposit areas of the High Middle Ages. (29)

The pilgrim's “confession”

No matter what his or her station in life, every pilgrim was required to make a preliminary confession prior to leaving on pilgrimage. This could involve a long list of sins over one's lifetime, or a focus on one particular vice or problem for which one sought help. This was especially true of compulsory pilgrims, the penitents and heretics who simply did not have a choice as to the focus of their confession.

Over time, especially by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, many travelers had started to disregard this policy and went on pilgrimages, regardless. Such rebelliousness greatly irritated the local priests and bishops. Officially, by strict canon law policy, the whole journey would be “wasted” by not making a confession beforehand. Yet many went anyway. Some of those who refused confession were excommunicated, but others were not. The situation varied greatly depending on where one was located. But the idea of making a confession—even privately—was most common, even if not so formally as in earlier medieval years.

The “pilgrim's vow”

In the eyes of the Church, one of the most important things prior to leaving on a pilgrimage was for pilgrims to take the “pilgrim's vow.” They would promise God that they would fulfil their pilgrimage and not quit beforehand—regardless of the difficulties encountered along the way. After making such a vow in public, with a group of other pilgrims, there was no turning back. The idea of “taking up the Cross” was part of this concept.

Medieval Church canon law decreed that no one could break a vow of pilgrimage and be saved. Given the medieval belief in permanent damnation and the eternal fires of Hell, this absolutely rigid policy contributed to an environment of fear. Countless rumors would make the rounds in the High Middle Ages about how various people had broken their vows to a saint when on pilgrimage and then horrific consequences resulted. One person was claimed to have been struck blind, another got leprosy, a third was paralyzed, and so on.

Hospice Saint Vincent de Paul in Jerusalem. (Mamilla, WMC)

Pilgrims were initially keen to travel and go on a pilgrimage. But, as many accounts show, halfway into it, having encountered bad weather, rotten food, infestation of vermin, bites from rats, bandits, thieves, ridiculously high prices and exchange rates, and other travails, some would be tempted to go “AWOL” and leave. But they feared that doing so would permanently damn their souls and forever ostracize them from society, their family, and their community. There was also the uncomfortable realization that their fellow pilgrims could report them—and their whereabouts—to Church authorities if they abandoned their vows. Thus, most pilgrims chose to endure the situation a bit longer. Others finally did leave—becoming pirates, merchants, living under cover. Many pilgrims felt trapped at various junctures, especially on the longer journeys.

Others had more positive experience overall and never felt a great need to leave a pilgrimage—although they often heartily complained the entire time! So the accusations of trivial “frolics,” “ribald songs,” and “wanton activities” often levelled at the entire concept of pilgrimage (especially those made closer to the time of the Reformation) may be seen in another light. Perhaps, such behavior was a coping mechanism, a bit of a respite from having to deal with all sorts of difficult and unpredictable circumstances that, quite frankly, few would choose to tolerate today.

What did pilgrims take with them? Staff, flask, mantle, hat and equipment

The standard items nearly every pilgrim traveling to various shrines would take included his famous staff, scrip (a leather satchel to carry goods), a good cape, a flask, a hat, sturdy shoes, money, foodstuffs, and, if possible, as one traveler's account advises—herbal remedies and ointment for very sore feet!

Whether journeying by land or sea, pilgrims would have as many as five symbols on parts of their clothing and gear. These might include a cross on their cape or cloak to designate themselves as being on a pilgrimage (these were often red, but rarely white—as white was the color for the penitent). A pilgrim's gray hat was often marked with a cross (and, as they went along, would also include the addition of various lead pilgrim's badges collected from their attendance at shrines along the way, such as the famed scallop shell from Compostela), a flask, and a donkey. Those who could would pack additional foodstuffs, blankets, and bedding—as they had heard that the usual dingy straw mats on the floors of the typical hospice or inn were often filthy or infested with vermin. Others would also try to pack healing ointments, herbs, and other medicines. Of course, wine was always desirable.

Where did they stay? Hospices, inns, taverns, and hostels

Hostels (also called ‘hospices’ in some medieval sources) provided accommodation on the major pilgrimage routes. Like medieval inns everywhere, they had to be able to cater to religious pilgrims—no matter what their station in life. As pilgrimage was required by canon law, it naturally became a major industry for innkeepers and hostels along the routes to the major shrines. Some hostels were run by monastic orders and tended to be spartan, but in somewhat better condition. Many commercial lodgings, on the other hand, did very little, or nothing, to make travelers' experience pleasant. Inns, taverns, and a fair number of hostels were dirty, noisy, and expensive, adding yet another series of problems for those on the road.

Few, if any, pilgrims ever slept well through the entire night. People often had to share a single room or bed, as robberies and violent crime were rife. Personal safety was a priority for everyone. One member of a group would sometimes rob others during the night. But just as often, the innkeepers themselves would overcharge and steal possessions during the night, or “shop” them to owner-friends at the next hospice down the road! Treachery was nearly everywhere so it was not unusual for pilgrims to say an extra prayer or two.

Almshouses

Almshouses were not the same as a hostel, hospice or an inn. They were originally part of a monastery—where alms and hospitality would be bestowed by the monks or nuns upon exhausted pilgrims, the ill, and the hungry. Understandably, they were quite popular during the heyday of pilgrimage.

The term alms means money given to the poor for charitable purposes. Religious organizations throughout Europe and in the East, including the various monastic and military orders, collected alms for the poor in the Holy Land. In certain areas, alms collection played a major role in assisting not only those on pilgrimage, but all Christians in need—in both the Holy Land and western Europe. Later, many of the larger almshouses developed into medical hospitals for the elderly, the poor, and the infirm.

View of the sea from Malta, looking towards the beautiful island of Gozo. (Karen Ralls)

“How” did medieval pilgrims travel?—by land and sea

While many pilgrimages were by land only—whether by walking or at times via a cart—many others were a combination of land and sea, depending on where you were going. Personal security and safety and freedom from disease—in addition to the expense and other concerns of the journey—were uppermost in the minds of pilgrims. Medieval legends and songs still survive about treacherous sea journeys and their pitfalls.

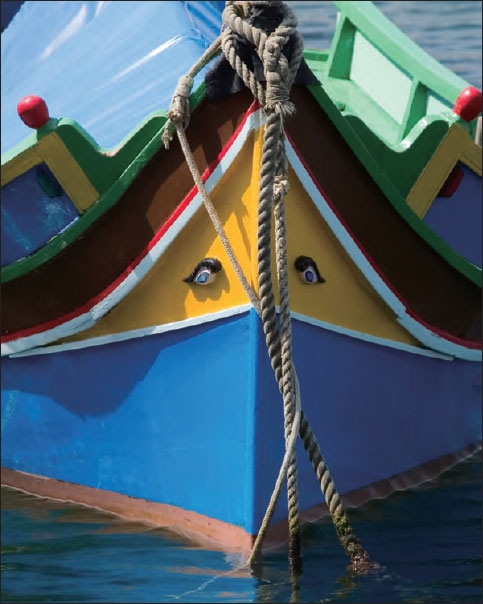

Traveling by ship was usually in great demand as this was the best route to the Holy Land. However, the ships were very crowded, and the journey, often under trying circumstances, could take many weeks or months depending on destination.. Passing the long hours could be challenging without room to move around much, so some pilgrims would keep diaries, sing, or play games such as cards, dice, or chess. Ship's captains made use of protective symbols and visual reminders to invoke the special protection of Mary as Stella Maris—the “Star of the Sea. The Christian worship of Mary is reminiscent of the Egyptian reverence for the great goddess Isis, protecting the heavenly sea of the night sky and the earthly ocean. Again, “Like Isis, Mary became the patron of ships and sailors, life-saving in an age of nightly navigation by stars. In Sicily, for instance, where once the eye of Horus, son of Isis, was painted on the prow of the local fishing boats, now the sign of the Virgin takes its place.” (30) Mary was sometimes known as “the net” and her son as the divine fisherman—just as in Sumeria, Dumuzi, the son-lover of Inanna, was called “Lord of the Net.” A similar theme is echoed in the image of Christ as “fisher of men.” (31) Even today, fishermen, yachtsmen, and sea captains all over the world paint an eye on the prow of their ships, as the photos on page 259 from a port in Malta illustrate.

Eye imagery, an occulus image painted on the front of this colorful, modern-day Maltese ship hull, as protection for sailors from possible dangers at sea. (Simon Brighton)

Close-up view of an eye imagery occulus carving, added on this ship's hull as a protection for sailors at sea. (Simon Brighton)

Maritime trade and pilgrims: the role of the knightly Orders

The vast theater of operations of the Knights Templar not only involved activity on land, but also sea. For two centuries, the Templars needed ships to carry money, animals, military equipment, men, and supplies from Europe to the Holy Land, where they were desperately needed for the Crusades. Certain Templar ships were also used to provide safe transport for Christian pilgrims. This was a reliable means of transport for pilgrims and a revenue source for the Order. Templar ships were generally not warships, but more often, simple galleys that were constantly on the seas, on the move, not staying in any one location for any period of time. In a climate where great danger, including piracy, was rampant, one can easily understand why a medieval pilgrim would choose to travel securely with the Templars. (32)

The concept of the secure protection of pilgrims was given by the Church as one key reason for the founding of the Templars. Following the First Crusade in the late eleventh century, increasing numbers of Christian pilgrims risked their lives from attack by the Saracens and flocked to Jerusalem from all over Europe to see the holy sites. An eyewitness account by one traumatized pilgrim in the first decade of the twelfth century reported that Saracens lurked day and night in the mountains and caves between Jaffa and Jerusalem, ready to ambush Christians journeying to and from the coast. Similar frightening accounts kept arriving in Europe on a consistent basis, creating great concern for the welfare and security of travelers.

In the early twelfth century, extra men and equipment were rarely available to patrol the pilgrim routes en route to Jerusalem, or to escort new arrivals from the ports. Saracen robbers were regularly attacking, robbing, and killing Christian pilgrims. Accounts describe conditions on the roads that were so horrific no one wanted to even stop to bury the dead for fear of being attacked or murdered. Corpses, partially eaten by wild animals, were often seen piled up along the route. There was no organized system in place to provide food, drink, or shelter for pilgrims on the road, so by the time people arrived at Jerusalem, they were often exhausted, hungry, distressed, and sometimes quite ill.

What is seldom acknowledged today is the fact that, especially after the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, a time of increasing disorder on many fronts, various renegade brigands from nearly every Western nation (Englishmen, Frenchmen, and Germans), common criminals, and a few alleged “former Knights Templar” and other ex-crusaders were said to have preyed on some pilgrims as well. Such criminals ended up living in the hills of Palestine, side by side with Arabs “for whom brigandage had been a way of life for centuries.” (33) Sadly, the scarcity of surviving historical records in certain regions makes tracking these cases quite difficult. Over time, archaeologists and historians hope that more medieval records will surface.

Role of the Knights Hospitallers and medical services for medieval pilgrims:

Who were the medieval Knights Hospitaller? That is the shortened name of the military religious order now properly called “The Sovereign Military and Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, called of Rhodes, called of Malta.” Still an official religious order in the Catholic Church today, the medieval Hospitallers were originally established to medically treat pilgrims traveling to (and in) Jerusalem. Their hospital in Jerusalem was a major beacon of hope to many hungry and exhausted Christians, provided they made it that far. As many more increasingly weary or badly ill pilgrims began to arrive in the Holy Land, a much greater demand for medical services became apparent.

Image of medieval Knight Hospitallers

Although it is not known for certain how long the Hospitallers' earliest hospital or hospice had been in Jerusalem—due to the general lack of surviving records about it from the medieval period—they were one of the earliest charitable orders and were well-established by the early twelfth century. About the year 1080, a Benedictine abbey called St. Mary of the Latins started a hospital just to the south of the Holy Sepulcher, staffed by monks from the abbey next door. A women's hospice dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene was founded nearby. Today, it is believed that this early hospital was financially assisted by wealthy merchants of the Italian port city of Amalfi, and that it was actually established as early as 1020 CE. Evidence also exists of a European hospital established in Jerusalem as early as the ninth century.

The dedicated and energetic supervisor of the Benedictine hospital was named Gerard. On February 15, 1113, Pope Paschal II sanctioned the establishment of the Order of the Hospital (the “Hospitallers”) by papal bull. The Order was dedicated to St. John the Baptist and placed under the protection and authority of the Holy See. The Benedictine hospital became independent of its monastic “parent” and was now run by the Hospitallers. It was said to have held up to 2000 patients. Gerard became the first Grand Master of the Hospitaller Order. He died in 1120. His skull is now a highly revered relic preserved in the Convent of St. Ursula in Valletta, the capital of Malta. (34)

Krak de Chevaliers Castle in northwest Syria (James Gordon, WMC)

Castle Pilgrim, Athlit. (![]() WMC)

WMC)

All Hallows by the Tower Church, London. The altar stones from “Castle Pilgrim” in the Holy Land, brought back to London by the medieval Knights Templar, in its undercroft museum today. (Simon Brighton)

The Krak des Chevaliers

A brief mention should be made here of the Krak des Chevaliers, a well-known Knights Hospitaller fortress in Syria during the years of the Crusades. It would have also been quite familiar to pilgrims traveling in the area. It has sometimes been confused with one of the major castles of the medieval Knights Templar, especially their highly popular Atlit, “Castle Pilgrim,” another favorite stop along the pilgrimage routes.

Krak des Chevaliers was built by the Knights Hospitaller in approximately 1131-1136. In 1187, its powerful, dramatic lord, Reginald of Chatillon, attacked Saladin's forces. In the following year, Saladin attacked and took Krak des Chevaliers. The fortress was later recaptured by the Crusaders again. It finally fell to Baybars, a Muslim leader, in the late thirteenth century. (35) Due to conflicts in the region in more modern times, the building has suffered further damage.

Templar Castle Pilgrim (Atlit) and its connection to All Hallows by the Tower Church in London

The important English church—All Hallows by the Tower—is located near the Tower of London on Tower Hill. It was one of the sites in medieval England identified with the arrests of the Knights Templar. As explained in The Knights Templar Encyclopedia, although this church has tangential connections to the Templar order, it was not built by the Knights Templar. However, the altar stones of All Hallows Church—that even today hold up its undercroft chapel High Altar (and once dubbed the “Vicars Vault”)—were in fact brought back to London from Castle Pilgrim at Atlit by returning English medieval Knights Templar. The Templars built Castle Pilgrim during the Fifth Crusade, and named it in honor of the many pilgrims who helped them build this powerful stronghold.

The history of the Tower Hill area in London goes back long before the arrival of the Romans in early Britain. The All Hallows-by-the-Tower church location, itself, also has a long and varied history. For over thirteen hundred years, a church has stood on this site. Founded four hundred years before the Tower of London, the earliest All Hallows church was originally built in 675 CE by the monks of Barking Abbey—making it one of the oldest churches in London.

But its early Saxon roots are also in evidence. Sometime before 675, the historical record shows that Erkenwald, the Bishop of London, founded a Saxon Christian community at Berkynge (Barking), seven miles down river, and made his sister Ethelburga the first Abbess. Barking Abbey had a large estate near All Hallows and the church there was most likely used by its representatives.

In the early fourteenth century, after the arrests of the English Templars began in 1308, the knights were imprisoned and interrogated in the Tower and in the church. Centuries later, the 1940 German bombing of London revealed a large Saxon arch with Roman bricks in the church. Still later, in 1951, half of a circular wheel-head of a Christian cross with Anglo-Saxon inscriptions was found under the floor.

The Norman church on the site of the early Saxon building was built ten years after the Tower of London, adjacent to the church. The only remains of this Norman place of worship is one isolated pillar embedded in the wall of the vestry and a few fragments in the undercroft. There is a museum in the crypt which is of interest to many.

In the middle of the thirteenth century, a chapel dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary was built on the other side of the road to the north. This (now destroyed) chapel was known to have had a connection with the medieval Templars as well. The chapel's foundation unfortunately disappeared in the sixteenth century, the time of the Reformation. Attached to this chapel of St. Mary was a guild, which was later raised to the status of a Royal Chantry by Edward IV in 1465.

The present All Hallows church has a number of early associations with other major guilds. These include the Worshipful Company of Bakers, Gardeners, and the Watermen and Lightermen. On a more “gothic” note, so to speak, history records that headless bodies were often given Christian sanctuary here in the All Hallows' churchyard after their gruesome dismemberment on Tower Hill.

All Hallows by the Tower Church (London): its American historical connections

All Hallows by the Tower church is often a special site of interest on the itinerary of Americans visiting London. This church very narrowly escaped the tragic Great Fire of London in 1666, and was only saved by the extraordinary courage and quick thinking of one man, Admiral Penn—the father of William Penn. William was baptized in All Hallows by the Tower Church on October 23, 1644 and educated in its schoolroom. William went on to America in 1682 to found what would later become the U.S. state of Pennsylvania as well as the city of Philadelphia, especially valuing the principles of religious liberty and freedom of thought.

The sixth President of the United States, John Quincy Adams, was married at All Hallows by the Tower Church in 1797. It is also the official London church of the St. James branch of the highly regarded American historical and genealogical charity, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Visitors continue to visit the Tower and the church today. (36)

The famed medieval Alpine hospice of Great St. Bernard pass

After the suppression of the Templars by papal decree in 1312, the majority of the Templar lands and estates in Europe were given over to their previous rivals, the Hospitallers. The work of the Order of St. John, therefore increased significantly from this time.

In the region of the Swiss and Italian Alps, for example, by the second half of the fifteenth century, there were no less than twenty-nine associated hospices close to hand to the pass of Great St. Bernard. This famed medieval hospice network, mainly in the dioceses of Sion, Lausanne and Geneva, was a huge enterprise. Founded in 1050 by a charismatic, itinerant preacher in north Italy named Bernard, Archdeacon of Aosta, he became known after his death as St. Bernard of Mont Joux, the mountain above the facility. The famed hospice was built on the site of an earlier medical facility that had been run for many years from the old monastery at Bourg-St-Pierre. In part, the new building was constructed with stone from a Roman temple to Jupiter. A key site on the medieval pilgrimage trail, it was visited by people of all ranks, including the occasional visit by emperors or a pope. Napoleon, himself, stayed there many centuries later.

Where did they visit on a pilgrimage? Major sites and shrines

Among the most popular destinations for medieval pilgrims were the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and other sites in Jerusalem; major churches and religious sites in Rome; and the shrine of St. James the Great at Santiago de Compostela in Spain. If one had the time and resources, other eastern destinations could include St. Catherine's monastery in the Sinai; the famed Castle Pilgrim of the Knights Templar at Atlit; Mount Athos in Greece; Constantinople; the Hospitallers' fortress of Krak de Chevaliers in Syria; and sites in Turkey, Cyprus and Rhodes. St. Thomas Becket's shrine at Canterbury; Durham and its shrine of St. Cuthbert; Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset; and the hugely popular shrine of Our Lady in Walsingham in Norfolk are examples of some of the major English pilgrimages sites.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (James Wasserman)

Mount Sinai, near the fourth-century Saint Catherine's Monastery in the south of the Sinai Peninsula, has been a pilgrimage site for at least two thousand years. (James Wasserman)

But no matter where a pilgrim was originally from, he or she would try to take in as many acts of worship, absolutions and good deeds as one possibly could on pilgrimage.

Other popular major stops along the way to Rome, for example, included a visit to the shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne; another was to St. Theobald in Thann; and certainly no one would want to miss the beautiful Black Madonna shrine of the Virgin Mary at Einsiedeln when passing through Switzerland. As mentioned, on the way to Compostela, if one were traveling through France, many pilgrims would ensure they visited the four important shrines along the way at Chartres, Vezelay, le Puy, and Rocamadour.

While traveling was dangerous, suffering could be meritorious:

Enduring hardships along the way was to be expected; pilgrims long understood their journey would be a perilous one. As mentioned earlier, sometimes the hardships were so great that pilgrims would die along on the way. An English pilgrim, who had aimed to reach the shrine of St. James at Santigo de Compostela but died along the way, was given a major, touching tribute by those back home with a carved effigy in the church of Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicester. This (unnamed) man is portrayed with the classic medieval pilgrim's clothing and dress; his hat and scrip are adorned with scallop shells, the emblem of St. James the Great. (37)

Such suffering was seen as a meritorious act, serving to expiate the heavy weight of sin. The idea of enduring some degree of pain and suffering to ultimately reach the final pilgrimage destination was expected—if one did not endure some pain, there would be no gain towards getting to Heaven.

Some pilgrims deliberately added to their own burden: walking barefoot, or wearing a hair shirt; some would voluntarily flagellate themselves. Eventually the persistent problem of so many self-flagellating pilgrims in the town squares and centers of certain Italian cities had to be dealt with legally! The situation became untenable for local businesses and individuals, to say the least, all of whom became increasing tired of the shrieks, sobs, and bloody antics every pilgrimage season, which occurred at least twice a year.

There were debates about whether women should go on long pilgrimages at all, due to the dangers for their safety and “losing their virtue.” Virtuous wives were, strangely enough, often rather keen to go on pilgrimage in spite of such dire warnings, as a number of historians and authors, including Chaucer, wryly note.

So ... let's now take a look at what a real pilgrimage journey was like—from a contemporary report on the road to Compostela ...

What was it really like?

The role of the “pilgrim's guide” should not be underestimated. Like modern-day travel guide books, many returning medieval pilgrims recorded their thoughts, candid advice, and experiences—good and bad—about their journey for others. What happened to them; what shrines were the best; which hospices or inns were good and which were notorious; where to get the best exchange rates; what and who they encountered along the way. In short, they would report “the good, the bad and the ugly” for the benefit of future travelers—often revealing their own biases, prejudices, and tastes in the process.

One of the most famous of these guide books, The Santigo Pilgrim's Guide, is a classic in its field. It was written by a Frenchman in the mid-twelfth century, the heyday of the great age of pilgrimage. (38)

But first we need to know: who was St. James and where is Compostela (the “field of stars”)?

St. James the Great

The “road to Compostela” grew around many legends and controversial theories about one of Christendom's most famous saints—James the Great (d. 44)—and his connection to Santiago. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints comments that St. James was an:

apostle and martyr, described in the gospels as the son of Zebedee and the brother of John, James was one of the three witnesses of the Transfiguration of Christ and his agony in the garden of Gethsemane. He was also the first apostle to die for the Christian faith, being put to the sword at Jerusalem by King Herod Agrippa ... No early documents claim either that James preached the Gospel in Spain or that he was buried there. Of the two claims, the former is the earlier (7th century), the latter (9th century) the less likely; neither nowadays commands much credence outside Spain. The heyday of Santiago de Compostela was from the 12th to the 15th century ... Cluniac and Augustinian monasteries were built along the roads especially in northern Spain, to provide hospitality for the pilgrims . the shrine of Compostela is on the site of an early Christian cemetery ... his identity, however, is unknown. A conjectural claim has been made to identify him with Priscillian ... (39)

Although the multifaceted St. James legend has not been verified by historians, the mythic site of his tomb was largely unknown until the ninth century (813 CE). A hermit named Pelayo was said to have been led by a spiritual vision to the burial place itself, which, at that time, was in the forest of Librédon:

A report of this discovery was sent to the local bishop at Iria Flavia, then the seat of the bishopric in Galicia, where the story of St. James' mission in Galicia and of his burial in a necropolis located somewhere in the forest of Librédon, had been kept alive. The bishop, Theodomir, hastened to visit the site and was able to accurately locate the tomb and authenticate the relics as those of St. James. Since Spain at this period sorely needed a new champion to inspire Christians against the invading Moors, the discovery came therefore at a most propitious moment. As soon as he heard the news, King Alphonse II declared Saint James the patron of his empire and had a chapel built on the site of the tomb. (40)

After this, pilgrims in ever-increasing numbers began to follow the Camino de Santiago (“Way of Saint James”) to visit the tomb. The city of Santiago de Compostela started to grow up around the chapel. A powerful “legend was born,” sustained ever since. Compostela was arguably one of the greatest pilgrimage routes in all of medieval Christendom, still popular with many today, who wish to tread its “field of stars.”

But what was traveling this famed road really like in the Middle Ages? Thankfully, we have some twelfth century “travel guides” written by eye-witnesses who traveled the road and came to know it well.

The Santiago Pilgrim's Guide

The Santiago Pilgrims Guide dates to 1145. It is an especially candid travel guide and gives a potential pilgrim the real “lowdown” on traveling to Santiago—its joys, healings, sorrows, troubles, dangers, and more.

It illustrates how popular pilgrimages were to the northwest of Spain—ranging from the larger, spontaneous mass pilgrimages to the carefully planned individual journeys. It gives much advice to pilgrims who would like to make the journey, and in doing so, is quite opinionated at times—nothing like an “objective” news report today! The guide is invaluable to medieval historians, as are others like it, as it provides a glimpse of one pilgrim's experience directly from the traveler himself.

The book is equivalent to about fifty typewritten pages, and deals with nearly everything that might concern a pilgrim—or, for that matter, many travelers today. The author gives frank advice on roads and rivers; bridges and hospices; food and drink; weather; the natives in each region through which one would pass; saints who must be honored on the way; and finally, specific advice on what to do once one finally arrives at St. James' Cathedral in Compostela. Legends and anecdotes abound. One of the most famous being the “flowering staff' motif—where, at a particular place, a pilgrim's staff stuck in the ground is said to have grown green shoots. This is reminiscent of the wonderful folktale of Tannhauser, whose staff, upon returning from a pilgrimage, sprouted green shoots.

The author describes the four main routes through France to Compostela to Santiago: Saint-Gilles in the Bouches du Rhone; Le Puy in the Massif Central; Vezelay in Burgundy; and Tours on the Loire. Beyond the Pyrenees, these four routes joined at Puente la Reina to form the single pilgrim's way to Santiago—along which perhaps millions in the Middle Ages went, and parts of which are still in use today. So many traveled along this legendary path—the rich and poor, the young and old, male and female, educated and uneducated, the healthy and the sick, those who wanted to give thanks for help received in a desperate situation, those who wanted to escape boredom and mind-numbingly menial work, nobles and kings, pardoned criminals, adulterers, greedy merchants, those who wanted to ask for a special blessing or fulfill a vow, and, of course, those who were adventurers or rogues of various sorts. (41) The variety was endless.

As we learn from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, pilgrims on the road—although ostensibly on a sacred journey—weren't necessarily always as “pious” as we might expect. The author of our travel guide also warns all pilgrims about dangers from nature and from their fellow man. Death or terrible illness could threaten the traveler if he drank water from the wrong river or stream, or if he ate meat or fish that were not fresh. Robbers lurkedalong the way, with certain areas much riskier than others. In describing the virtual “no man's land” through the Landes in southwestern France, he candidly says,

... these will be days when you will be utterly exhausted! For it is a god-forsaken, flat region with very few stopping-places, as if bereft of all the good things of the earth, without bread, wine, meat, fish, with no running water or springs. There is only sand in abundance. (42)

However, he goes on to reassure the pilgrim that there is plenty of honey in the area and various kind of millet. And he gives this gem about traveling there in the summer months: “If you chance to travel through this region in summer, protect your face carefully from the giant flies: they are called wasps or gadflies here, and there are great swarms of them.” (43)

The author reveals his own prejudices and viewpoints. He does not travel to Santiago as a poor penitent, but describes the pleasures of the table along the way—not unlike today's Michelin and other guides. There are many references to good wine, meat, and white bread—which only the rich could afford at the time. He describes a region, its food and its people in often brutally candid terms. In one of his passages on Castile, he informs his readers that the area is rich in gold, silver, costly materials, and unusually strong horses, and that it is, “fertile and produces a great quantity of bread, wine, meat, fish, milk and honey; the only lack is of wood. Just one word about the people here: they are ill-tempered and profligate.” (44)

Sometimes he speaks very well of a region and its people. At other times, he will entirely condemn the whole populace, as he doesn't seem to accept that people in other countries may have an entirely different way of life. He praises the people of Poitou:

Leaving Tours one approached Poitou, an exceptionally pleasant and blessed region. The people of this countryside are able-bodied and warlike heroes ... It would be hard to find men who are more generous and hospitable than they are. (45)

However, the farther south the author travels, the more critical his remarks: with descriptions of the “peasant speech” of the people in the countryside around Saintes; the “even coarser” people around Bordeaux; and the (unfortunate) Gascons, whom he feels have completely fallen prey to drink, gluttony and other excesses. Further south, we learn that the speech of the Navarrese reminds him of the “yelping of hounds” (!) (46) But a thoughtful postscript, possibly penned later by another author, says that the Navarrese are brave fighters and that they give generous offerings to the Church.

He curses the unscrupulous ferrymen at the foot of the Pyrenees. There were two Styx-like small rivers there that could only be crossed by pilgrims with their help. So the ferrymen took crass advantage of the pilgrims, and demanded from rich and poor alike one gold coin for taking a man across the rivers and four for a horse. They had a dugout boat that was made from a tree-trunk, he tells us, that was very small and especially unsuitable for transporting horses. He warns about the ferrymen:

I wish with all my heart these devils would go to Hell!...If you get in this boat, take care: you will soon be in the water! ... After they've taken the money, the ferrymen often let so many pilgrims get in that the boat sinks and they all drown in the water. The worthless boatmen then let out a howl of joy and take all the drowned men's belongings.”.. (47)

He naturally warns pilgrims to only get in a few at a time, and advises that they should let their horses swim across themselves, if possible, by leading them by the reins.

Then, he curses the “wicked highway robbers,” adding that if one were lucky enough to have survived the ferrymen, he would next encounter a treacherous new hazard in the “inhospitable and densely wooded” Basque country, “If the pilgrim sees the local inhabitants, his blood will freeze.” Next are complaints about the so-called highway toll men—of whom there were apparently many. Guarded by two or three men with lances, they approach the pilgrim and forcibly demand an unwarranted toll. He warns

If the traveler should think of refusing them the money they demand, they kill him with their cudgels and appropriate the sum. Then with vituperations they strip their victim naked ... (48)

If that isn't enough, consider this: the author also practically begs for heavy punishments for those directly and indirectly responsible for this sorry states of affairs—the king of Aragon, tax collectors, and other officials—all of whom are in charge of the highways and waterways. He says they let these crimes happen. But most damning are his words for the clergymen he encountered:

The priests are also responsible, who know about these crimes: they give absolution to the wrongdoers, welcome them into their churches, celebrate the mass with them and give them communion. (49)

He suggests that all directly and indirectly involved—clergymen or laymen—should be excommunicated; and believes they should remain excommunicated until “they can be pardoned after a long, public penance—andshow proper restraint in their demands for money.” So, it would appear, there was plenty of “fraud” in the pilgrimage business, too, and not just the more well-known abuses involving relics (as will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter).

The guide is full of much helpful, practical advice for pilgrims, especially about dangerous areas or situations they might encounter. Since we know, it was one of the more popular travel accounts, it gives us a good idea of what a medieval pilgrim could encounter along the way. Every pilgrim's journey was different, of course, but we know it was long and grueling for many, often with unexpected events. We also know that others were more fortunate. Some of the more popular shrines would attribute a special word or pun for its pilgrims: for instance, a male pilgrim “on the milky way to Santiago de Compostela is also known as a ‘jack,’” an English word play on [St] Jacques. (50)

The Spanish pilgrimage hub of Santiago has spawned other orders and organizations through the centuries. Let us now examine some of these.

The Knights of Santiago

One such order is the twelfth century Knights of Santiago. It was an influential knightly military order that played a key role in the Christian Reconquest of Spain and received the greatly coveted papal recognition. It was initially formed to protect pilgrims going to the tomb of Saint James at Compostella from Moorish bandits. Thirteen knights began the order by dedicating themselves to the monastery of Sant Eloa at Luho in Galicia and adopting the Augustinian rules. Their monastic allies also provided hospital and medical services to pilgrims going to and from Compostella. (51)

The modern-day Confraternity of St. James

The Confraternity of St. James is a modern charity, founded in 1983 to bring together those interested in the pilgrimage to Compostella. It has continued to fan the enthusiasm for traveling the famous road to Compostella—affectionately known as El Camino. As Philip Carr-Gomm states in Sacred Places, its former chairperson Laurie Dennett describes the rich tapestry of travelers, varying beliefs, and cultural traditions that often influenced each other on the way to and from Compostella during the High Middle Ages:

With the pilgrims to Santiago, and often as pilgrims themselves, there came French stonemasons, German artisans, Tuscan merchants, Flemish noblemen, English and Burgundian crusaders. The more educated among them brought, as part of their intellectual baggage, Provencal lyric poetry, Slav legends, Carolingian and Scholastic Philosophy, new building techniques, and endless music. On the Camino Frances all these influences intermingled and returned to their lands of origin, along with Arab aesthetics and science, medicine and culinary arts. (52)

Caravan of the last chance: a modern-day trek from Belgium to Santiago

A modern day account of El Camino poignantly reveals how this pilgrimage continues to significantly heal and transform lives. In this case, in 1982 a juvenile justice judge in Belgium assigned two delinquent boys to go on a pilgrimage to Santiago, with a trained guide, to see if the grueling four-month journey would help them. The boys had been living in institutional care for a long time and were starting to get involved in more serious criminal behavior. The judge's aim was for the boys to complete the four-month walk in good understanding and good order, showing respect for the many cultures and people they would meet during their walk. If they successfully completed the journey, the judge said he would let them go to start a new future and an adult life.

The travel that “never stops, never comes to an end”: a travel guide's report

Walter Lombaert was their guide. He lived and worked in Belgium at the Oikoten community, a charitable organization which aims to provide alternatives for young people in special care. He explains his story: