Gothic Cathedrals: A Guide to the History, Places, Art, and Symbolism (2015)

CHAPTER 8

SCULPTED MARVELS IN STONE AND WOOD:

From Gargoyles to Saints

It seems that carvings and symbolism are nearly everywhere in a Gothic cathedral, both inside and out—Gothic wonders all their own. Stone carvings abound on the walls, tombs, ceilings, and around images of the patron saints. Wood carvings are also prevalent, as are certain relics. Art historians call the interpretation of such visual symbolism “iconography.” Visitors today often refer to many of the carvings as “beyond description,” “stunning,” or “too awesome to even try to explain.”

What is “symbolism”—and can it ever be truly defined?

Each of us is unique, and our perceptions differ. We all have our own “take” on what we see and experience with medieval carvings. How does a modern-day person understand these medieval images? Can we, or should we, even try to fully grasp their meaning? Or, are they not meant to be intellectually analyzed, but instead, experienced at a deeper level? The latter would have been far more likely in medieval times. We discussed in chapter 7 that knowledge was visually communicated when fewer people could read. There are many views of what a particular painting or carving might mean. But which images tend to predominate in High Gothic cathedrals, and why? We will now take a look at this question.

In addition to the usual biblical themes one would expect, hermetic and alchemical symbolism are also present in some of the stone carvings. However, it is difficult to make any broad generalizations, as each cathedral is entirely unique regarding its symbolism. Many such choices were made on a regional or local basis, so there was never any neat uniformity regarding the specific images that would apply to all of the Gothic cathedrals. Likewise, no “one single definition” or explanation was intended, or, indeed, possible. Interpretation depends on perception. One art historian in London explains that “because of the traditional Italian bias in the study of thehistory of art, the sculptors of the late Gothic period in France, the Netherlands, and Germany have still to be recognized for their fundamental importance to the development of European sculpture.” (1)

Sundial angel, the “Angel of Chartres,” carved on the exterior of Chartres cathedral.

The idea that there are secrets concealed in art and architecture is not a new one. Certain types of carvings do tend to show up quite often in Gothic cathedrals—in fact, far more often than in other types of medieval buildings—as architectural historians have noted. Some of these Gothic carvings are quite unusual, featuring gargoyles, unicorns, or the Green Man, for example.

From the early twelfth century, a feeling that this was an age of change accompanied the new Gothic style. In sculpture, painting, book illumination, and the goldsmith's art, new styles emerged, contrastingly greatly with what had gone before. (2)

Cathedrals housed elaborately carved stone shrines for relics, tombs of saints, or general purposes. At times, the stampedes to see these works of art would become so great, that official shrine-keepers were employed, like security guards today. These security gatekeepers were officials called feretrars—such as those needed at Durham, Westminster Abbey, Ely, Chartres, and Christ Church Canterbury to protect visitors from injuring themselves or others. (3)

We discussed sacred spaces and energy vortices earlier. Currents of sacred force were highly regarded by some pilgrims in medieval times, but venerating a saints' relics was key. When a pilgrim would visit a shrine:

the belief was that the farther one stood from the object, the weaker was the effect. Thus, a person who hoped for a miracle cure needed to have direct or near-direct physical contact with the relic. Because of this tendency to radiate, if a sacred object is left unconfined and exposed, its powers will dissipate...[so]..for this reason, care must be taken to construct a strong container to house it that is made of materials that can “hold” the sacred force. (4)

In the Middle Ages, carvings of Night (Moon) and Day (Sun) are well-established, and commonly seen in various forms in many Gothic cathedrals. For instance, in one of the archivaults at Chartres, the carved figure of Night is illustrated as a blind person led by Day holding her hand. Other carved images of blindfolded females in medieval buildings include the Wheel of Fortune, Prudence, Sapientia (Wisdom), the ladder of Philosophy (as Lady Alchemy), Blind Cupid, and Blindfolded Death. (5)

During the Reformation, a taboo against the visual arts was adopted by some of the more austere forms of Protestantism. Their places of worship were devoid of art—a simple, stark environment. But the medieval cathedrals were the opposite. The late twelfth and thirteenth centuries reveled in sacred geometry, in architecture, structural adornment, and visual art—including sculptures, paintings, and ornately carved misericords andtombs.

The rise of the cathedral school of Chartres and its evolution into the University of Paris, caused an overall shift in emphasis to a deeper study of ancient philosophy. Some of the prominent scholars in Paris, such as William of Conches and Bernard Silvestris (later to become Pope Sylvester), helped spearhead this effort. Geometry, music, and certain themes from earlier classical Pagan literature and philosophy experienced a revival among scholars, who read and studied Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, and other Greek philosophers. One of the many ancient themes examined by the school was the symbolism of a sacred wedding, the union of soul and body, often depicted in medieval buildings as the story of Pluto and Proserpina. Their union was interpreted as “moon and the earth, and the wedding itself, a celebration by all that has been generated for the future of Nature.” (6)

Art of Memory and the importance of the Imagination via visual imagery

The term “art of memory” refers to the use of mnemonic principles and techniques to organize memory impressions, improve recall, and assist in the creative process of developing ideas. While long associated with training in rhetoric and logic, variants of these techniques have been employed in religious and magical practices since at least the first century BCE. The practitioner builds chains of emotionally striking images by visualizing them organized within schematic diagrams or placed inside the imaginal rooms of buildings.

The use of such memory techniques was revived during the Renaissance. As many cathedrals were built soon before the Renaissance, it is likely that clergy and key medieval philosophers in Paris and elsewhere in western Europe were already utilizing ideas. One scholar comments that “...it is fundamental to emphasize that the art of memory came out of the Middle Ages. Its profoundest roots were in a most venerable past. From those deep and mysterious origins it flowed on into later centuries.” (7) Indeed. By the late Middle Ages, there were those who revered this more ancient learning and revived its practice.

Professor Mary Carruthers, an acknowledged expert on medieval memory techniques and the history of the art of memory, agrees with the great British scholar, Frances Yates, adding that “... as the practical technique of reading and meditation, memoria, is fundamental” in medieval culture. (8) “In fact, intellectual history, as traditionally practiced, is not the best way to go about studying the role of memory in medieval culture.” (9)

In an age when knowledge was conveyed by visual means, the role of the Imagination was central. The often dramatic carvings and imagery on stained glass windows illustrated stories, allegories, myths, and folkloric themes.

In this late medieval climate, the use of visual imagery—and the imagination—was viewed as essential to help illustrate the relation of the temporal world to the world outside time. With carvings ranging from angels to daemons, the idea was to transport the viewer of these images—the pilgrim or traveler—“outside of time,” into another realm such as Heaven, Purgatory, Hell, et al, by stimulating the imagination to a fever pitch. (10)

Melchizedek figure carved in stone, portrayed with an empty chalice at Rosslyn Chapel. Compare this with a similar figure from Chartres on page 204, where a cubic stone is placed in the chalice. (Karen Ralls)

Many medieval carvings were brightly painted

One of the more surprising facts for modern readers to learn is that many of the stone sculptures we see in Gothic cathedrals today were originally very brightly painted, even garishly so. This was equally true for many other medieval buildings. (11) Just as an artist draws on past experience and on the tradition in which he or she works in order to create something new, so the makers of “a new civilization are the mediators of the great memory of history. Ideas, thoughts, images, symbols, that seem to have lost their power, are revived and suddenly seem apt and vivid in a new context...” (12)

Rosslyn crypt angel carving holding the shield depicting the engrailed cross of the St Clair family. (Karen Ralls)

Rosslyn crypt angel holding a scroll. (Karen Ralls)

Rosslyn crypt angel holding a heart. (Karen Ralls)

During Victorian times many of the colors of the earlier Gothic buildings and sculptures were whitewashed for conservation and preservation purposes. This method was thought, at the time, to be the best way to help preserve the stone. However, now that more advanced stone conservation techniques have been developed, it is unfortunately too late to restore the colors. We have some surviving examples of late medieval and early Renaissance brightly painted carvings, such as these angels in the crypt at Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland.

There are many symbols carved in stone, all around. Some types seem to occur more often than others, such as saints, angels, and various biblical and apocryphal themes. These we would expect in a cathedral. Other images may initially seem fascinating, strange, bizarre, out of place, or even delightfully eccentric.... like a donkey playing a lyre, the Fool, a centaur, a unicorn, dragons, acrobats, and so on. Some images only appear in a few cathedrals, others in many of them.

A carved figure of Melchizedek holding a Grail cup appears at Rosslyn Chapel, which was built in 1450, at the very end of the Middle Ages. Some Christian commentators believe that his appearance in these buildings in the medieval period may be a reference to Hebrews: 7 in the New Testament. It suggests that Jesus, the Davidic Messiah, had been given, or was born into, a priesthood of a more ancient sort than that of the Levite tribe.

An earlier example of Melchizedek appears at Chartres cathedral on the north portal. Here, Melchizedek is portrayed in the usual way. But he is holding a Grail-like chalice that contains a cubic stone protruding from the chalice. He is featured on the elaborately carved North Portal on the exterior of Chartres—which many consider some of the very best mid-twelfth century stone carvings that can be seen in Europe today. (13)

Melchizedek's cubic stone is thought by some to be the Philosopher's Stone. We recall that Wolfram von Eschenbach suggests in Parzival that the Grail is a “stone from Heaven.” The Grail was guarded by those he calls the Templeisen, a rather obvious reference to the Knights Templar, with whom his twelfth century storytelling audience would certainly be quite familiar. But this stone-within-the-cup carving of Melchizedek is also thought by some to be a metaphor for the symbolic “stone that the builders rejected,” symbolic of the long, often arduous inner spiritual alchemical process of personal transformation that was believed to take place within a serious seeker on the spiritual path. At Rosslyn, the Melchizedek angel-like figure is holding an empty chalice. He is portrayed as a silent, timeless observer through the centuries, an apt metaphor for the archetypal quality of eternity that Melchizedek represents. (14)

St. Piat stone carving in Chartres.

Melchizedek holding a Grail chalice with its cubic stone in the middle, indicating what may be representative of the allegorical cubic “celestial Jerusalem” (Dr. Gordan Strachan)

Close up of Grail chalice with stone, or as some allege, the bread of life. (Karen Ralls)

This is but one example of a stone carving in a Gothic cathedral, and how its deeper meaning or theme can be interpreted, and may open us to other perspectives, questions, and possibilities. Art historians continue to grapple with trying to find unified meanings for symbols, as do painters, artists, and photographers; but it is ultimately about how an individual experiences what he or she sees, rather than any intellectual definitions or ironclad answers as to exactly what a symbol means, and in what context. This is why I feel that it is often best not to thoroughly read the guide books prior to going to look at the carvings in any medieval building. Rather, simply absorb the atmosphere, look around, see and experience it all first—as a medieval traveler would have done—and, then, later, you can always read about it in more detail.

In England, it is fascinating to note the sheer diversity of types of stone that were quarried and used for medieval buildings. These include sandstone, limestone, granite, flint from East Anglia, and marble. Alabaster is found mainly in the North Midlands and the Trent Valley areas of England. (15) It was a favorite choice for tombs and effigies in the Middle Ages just after the Black Death (1348) and its use experienced a major revival during the Victorian period.

Worn stone carving of the image of a Phoenix on the exterior of Garway church, Herefordeshire, UK. In medieval times, Temple Garway was a preceptory of the Order of the Temple, the Knights Templar. (Karen Ralls)

Strangely enough, the image of a phoenix rising from the ashes—while, in the eyes of some, a rather obvious choice for Christian symbology as a symbol of the resurrection—is not nearly as often found in medieval church carvings. The myth of the phoenix is ancient, harking back to various spiritual and philosophical mystery schools. The phoenix is a beautiful mythic bird with an unusual fate: there is only one Phoenix alive at any given time. At the end of its allotted five hundred years, it builds a pyre of herbs, immolating itself from the heat of the sun's rays in the flames and dying in its current form. Yet from the ashes comes a worm that transforms into a new Phoenix, totally rejuvenated. It is described in many legends, tales and stories as a miraculous event. One of the few visual images of a Phoenix is carved in stone on the worn exterior of Garway church near Herefordshire, England, once the location of an earlier building—and an important English medieval Knights Templar preceptory. (16)

Vezelay—the marvels of the earlier Romanesque style

Intricate high quality stonework carvings were also created for Romanesque buildings, most notably those at the Basilica of St. Marie Madeleine at Vezelay in Burgundy in France. The Burgundy region had, as one commentator states, already proved “a mine for sculptures and capitals to inspire the sculptors and artists working under the influence of Cluny and later at Autun and Vezelay, Today, in Burgundy, passing from the museums to the churches we can see how the figure of the Celtic horse goddess Epona riding side-saddle reappears as the Virgin riding on the flight to Egypt.” (17)

Vezelay Romanesque

Themes for medieval stone carvings vary greatly, so it is impossible to generalize about them. At Vezelay, however, we see some rather unique imagery that builds on the theme of the number seven—and the allegorical seven deadly sins. “Envy” is symbolized here as a vicious slanderer of others. On one of the nearly two hundred ornate nave capital columns at Vezelay, there is a rather gruesome image of the slanderer's tongue being torn out. Other carvings nearby portray epic battles of mythical creatures symbolizing allegories of various types. Elaborate winged dragons, lusty musicians, even toads, are present—a great variety all around. (18)

Tympanum at Vezelay with its famed intricate stone carvings in the Romanesque style, some of the greatest of their time. (Jane May)

Vezelay, a dancing angel stone carving (Jane May)

Vezelay: carvings on capital pillar. (Jane May)

On other nave capitals at Vezelay, we see a lovely image of a couple toasting with two “Grail” cups, and on another, a beautifully carved dancing angel. (19) In the archivolt of the central tympanum the signs of the zodiac are featured—here, shown as an acrobat-like contortionist, whose spineless body makes a circle, connected with the month of January. (20)

Acrobats, tumblers, contortionists, jugglers, musicians and other public performers are frequently depicted in medieval cathedral carvings, their skills displayed for all to see. Ironically, although the austere St. Bernard of Clairvaux famously railed against spending money and time on what he called ornate “demons” in a house of God—i.e., the gargoyle and grotesque carvings—at one point he “commented favorably on the physical accomplishments of acrobats and jugglers, saying they were worthy of admiration and that even the spectators up in heaven were delighted by such games.” (21) Who knew! Sadly, such traveling entertainers were often scorned by many of the clergy and frowned on by medieval society. Physical distortions, as with acrobats, were thought to reveal human baseness, rather than athletic gifts and prowess.

Vezelay—intricate carvings on another pillar nearby. (Jane May)

People wonder about the philosophical underpinnings of the late medieval period, as relates to the body, sex, the flesh, and so on, and how carvings featuring such themes were justified for cathedrals. It was all part of how the medieval world view was changing, and how the Church was desperately struggling with various issues brought over from the ancient world. Church leaders attempted to integrate some concepts from Greek philosophy that they may not have agreed with, but simply could not ignore. They—like the early Church Fathers before them—were reading Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers and theologians when re-working their own system of medieval Christian theology. The huge dilemma of how to deal with the more bawdy, lusty, and earthy themes was a major problem for such men, given their vows of celibacy. Yet such themes were approved and included in carvings; they were viewed by the church as a teaching mechanism for the masses whose prurient curiosity with the forbidden could be used to attract them to sacred ground. Michael Camille, a leading art historian, sums up their dilemma rather well:

... Among the visions of Gothic art are thousands of inglorious human backsides that stare down at us from the roofs.and those startling bodily members carved in wood on misericords (supporting shelves on the backs of church chairs) that make their mockery right in the center of the great churches. This grotesquerie is an important aspect of Gothic art ... these inverted figures are also to be placed within the crucial aspect of image-magic in Gothic art. They look us directly in the face.in Gothic art the animal realm is usually clearly distinguished from the human. On every object, from the largest cathedral to the smallest brooch, man and beast, saint and serpent, are kept distinct. It is only in the monster, or babewyn, that their bodies connect. This was the very period in which “nature” was first used by the makers of canon law ... Many of the hybrid creatures, half-man and half-goat, that one sees in so many delightful setting in Gothic tapestries, Bibles, and psalters are visions of illicit couplings that could not be talked about, but could be pictured ... Gothic sculptors were always struggling to bring to life the very flesh which, according to the theologians, was already consigned to death. (22)

For the medieval clergy, devout pilgrim, or a visiting artisan or merchant the sheer variety of themes available to view in these teaching libraries in stone—from the angelic and sacred to the most secular and earthy—offered an opportunity to ponder all aspects of human existence. Such so-called “monsters” are there to provide a contrast—in addition to wit and humor—jolting the viewer into a new perspective. Irreverence and humor are considered to be quite important here. In the medieval Church's view, they were felt to ultimately serve a higher purpose, like the role of the Fool and his wisdom at a medieval king's court. While the Jester may seem merely humorous, even ridiculous, to some today, it was and is a profound theme to ponder from earlier time. The wisdom of the Fool was included in medieval courts to ensure that the king did not fall into arrogance during his reign, an important function. Perhaps much the same can be said for a number of these Gothic carvings.

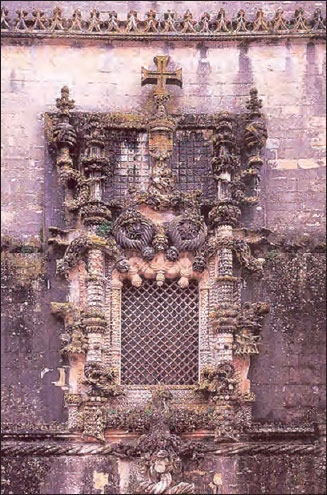

Tomar: the monastery of the Knights of Christ

Another example of interesting, if not somewhat unusual, stone carvings on the exterior of a medieval religious building, are those found at the monastery of the Knights of Christ (formerly the Knights Templar) at Tomar, Portugal. Here “the door and window openings are almost literally alive with carved sea creatures, plants, cables, and political emblems.” (23)

As we might expect, a major inspiration for stone carvings came from various descriptions of the apocalyptic visions of the heavenly, celestial city in both the Old and New Testaments, the greatest example being John's Revelation. But, even so, the emphasis is still on the realm of the imagination, of the overall flow of imagery. The more intriguing grotesque designs continue to delight—some of which came from the classical stories, Pagan myths, and ancient legends that the philosophers themselves became better acquainted with in the twelfth century. This is reminiscent of the cloistered monks in Umberto Eco's novel The Name of the Rose, who secretly enjoyed reading the “forbidden” texts hidden away in the monastery library, including books of philosophy and Greek comedy.

Tomar, west window of the chapter house, monastery of the Knights of Christ.

A scorpionic pew end Misericord located at Alford church, England. (Yuri Leitch)

Many wonder what the cathedral builders' contemporaries made of the ornate carvings in Gothic cathedrals. Well, actually, they were quite proud of them. There was a fair amount of heated rivalry between the rapidly growing towns, and between rival groups of stonemasons and wood carvers. There was competition as to which building exhibited the most exquisite and ornate carvings and which demanded the highest degree of skill. Master carvers were in great demand.

Lincoln cathedral, gargoyles

“Wooden Wonders”: Misericords carvings

As we walk around a cathedral today, we notice that some of the most fascinating and intricate designs are those carved in wood. It is hard to imagine the time-consuming, careful, tedious work of dedicated hands, hearts, and minds that were required to bring such wonders to life.

Misericords are a name for the elaborately carved tip-up seats that were provided to give some support to the congregation during the very long church services of medieval times. Each seat is often ornately carved from a single piece of wood, and are found in or near choir stalls. Many are elaborately carved bench ends, or as roundels, which may or may not have any connection with the religious subject matter of the main carving.

Wood panel carving of mermaid, Zennor, Cornwall. (Simon Brighton)

Artistic themes on misericords tend to be extremely varied, ranging from more obvious angelic themes to dragons, lions, foxes, and pelicans, which seem to have no relation at all to the main theme. (24) Known as “Bestiaries,” medieval archives displaying the many fascinating animal, plant, herbal, and imaginary beast symbolism prevalent in cathedral carvings are interesting to note. Francis Bond's groundbreaking early work, Wood Carvings in English Churches: Vol. I: Misericords (1910), helped to establish the earlier scholar John Romilly Allen's Bestiary discourse (1887) as, “the major key to the imagery of misericords. This book is organized largely according to the subject matter of the carvings ... subdivided into classifications suggested by Allen, that is, into Birds, Beasts and Fishes; Imaginary Birds, Beasts and Fishes; and Composite monsters.” (25)

Wood panel carving of mermaid at Ludlow. (Simon Brighton)

Others use natural imagery, beautiful carvings of a stunningly great variety of plants, animals, birds, and so on—both real and imaginary. So, for example, we also see unicorns, a Phoenix, or other mythical creatures, plants, or birds on misericords. Misericords tend to feature intricately designed carvings such as plants with entwining vines and leaves, and delightfully grotesque beasts, often straddling the boundaries between the plant and animal worlds. Some are purely mythical, stimulating the imagination of the viewer all the more.

More examples of Gothic misericord images include a lion and a dragon fighting, oak leaves springing from a satyr's mask, mermaids, male and female centaurs, a knight fighting a leopard, a locust of the Apocalypse, Pan playing his pipes, Green Man images, gargoyles, highly decorative swans, and so on. In some of the earlier French Romanesque buildings, we often witness wood sculptures of the Black Madonna, which modern visitors often ask to see. (26)

In England, two of the earliest misericords that have survived are at Christchurch Priory in Dorset, dating from the mid-thirteenth century. But most that have survived in cathedrals and churches are a century or two later. (27) In England, a long-time favorite theme for misericords are carvings of St. George slaying the dragon, such as this image at Boston, Lincolnshire.

There are also misericords of fascinating dragon-like creatures such as the wyvern—a kind of two-legged dragon, with “a serpent's tail, eagle's legs and the head and wings of a beast ... [it] differs from a griffin,” which was conceived of as a noble creature. According to John Mandleville's Travels, the griffin is stronger than eight lions and more powerful than a hundred eagles. (One is tempted to add: no mean feat!) Exotic, elaborately stone-carved dragons in many forms also feature prominently as gargoyles on the exteriors of cathedrals, but perhaps even more so carved in wood as misericords. As one elderly guide at a major cathedral put it, rather amusingly, it is “quite intriguing indeed” to see a myriad of exquisite varieties “right on the seats under and next to you in the choir stalls during the services.” (28)

Sea themes, too, often proliferate as elaborate wood carvings with mermaids, sirens with musical instruments, fishes, and various types of mythical water creatures. For example, the mermaid of many a cathedral wood carving is depicted carrying a comb and a mirror, or she is shown holding a fish in each hand. At Boston, Lincolnshire, she carries a musical instrument, an allegory in medieval times believed to be symbolic of the dangers of temptation; her musical recorder is shown as lulling the sailors to sleep. This is reminiscent of Homer's famous Greek epic, the Odyssey, where the hero Ulysses encounters the difficult challenge of having to pass the treacherous “island of the Sirens.” As a mortal man, he can only do so by taking extreme precautions against their temptations; as the story goes, he cleverly stopped the sailors' ears with wax and tied himself to the mast, thus enabling them all to pass through the area and survive the haunting melodies. Art historians note that in Ulysses' time, visual images of sirens were often depicted as bird-sirens; it is only later that we tend to see an evolution into fish-siren imagery; later still, they were shown as mermaids. (29) Other examples of wood panel carvings featuring mermaids are at Ludlow, England, and Zennor, Cornwall.

Objects in a cathedral sacristy or treasury

Gothic cathedrals also contained precious objects that served specific liturgical functions and were extraordinary works of art in their own right. At first sight, it might seem that displaying medieval works of art in a museum or church visitor center today is an act which separates the objects from their original contexts. Actually, this isn't the case, as small-scale, costly works of art were, in a great many cases meant to be openly displayed in the crypt (sacristy) or in a secure treasury area right next door to the cathedral. Such objects include liturgical items like candlesticks, censers, beautifully-illuminated book covers, vestments, crosses, small statues, and so on. They were often carved of ivory or metal. Such displays of medieval art can still be seen today in some of the Gothic cathedrals, or in art museums, like the V&A Museum in London.

But alongside these kinds of objects, the cathedrals and abbey churches also contained reliquaries for the sacred relics of saints. These, by their very nature, were intended to be venerated by the faithful. They are constructed of the most expensive materials. The reliquaries were often the aesthetic focus of the whole church, sometimes occupying a position of great importance behind the high altar—as may be seen today in the Shrine of the Three Kings in Cologne Cathedral. The relics of saints were the most important possessions of medieval churches and cathedrals and drew pilgrims from far and wide. The donations they brought when visiting were a critical financial resource.

Once important relics were acquired, their shrines would be built by the best craftsmen that could be found—the goldsmith, the ivory carver, the enameller, the blacksmith, for example. In the case of St. Denis at the time of Abbot Suger, the treasures of the cathedral were displayed openly within the church; but there is ample evidence that certain rooms were reserved, either inside the church or nearby, for the safekeeping and display of the most precious objects. St. Peter's in Rome had a separate treasury beginning in the fourth century—quite early. Perhaps not surprisingly, it was consistently plundered throughout the Middle Ages and later, so that now its contents reflect mostly post-Renaissance donations. The storage and safekeeping of such valuable objects were a major concern for every medieval cathedral—then and now.

One precious relic that has thankfully survived is Abbot Suger's Eagle Vase, a Late Antique period porphyry vase that has twelfth century additions. Suger made a greater effort than most to find ancient classical objects and then incorporate them into his medieval altar vessels. The porphyry vase, which he transformed into an ampulla with the gold head and wings of an eagle, is one example. (30) This extraordinary object can be seen today in the Louvre. We are especially fortunate to have the object intact, along with Abbot Suger's comments describing the circumstances of its manufacture. Renowned art historian Erwin Panofsky shares Suger's words in Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St. Denis and its Art Treasures:

we adapted for the service of the altar, with the aid of gold and silver material, a porphyry vase, made admirably by the hand of the sculptor and polisher, after it had lain idly in a chest for many years, converting it from a flagon into the shape of an eagle; and we had the following verses inscribed on this vase: “This stone deserves to be enclosed in gems and gold. It was marble, but in these [settings] it is more precious than marble.” (31)

Suger's re-use of this vase points to the key to the survival of large numbers of Late Antique and Early Christian treasures. Unless they had been incorporated into later medieval objects, it is doubtful that many would have survived at all. (32)

Many objects were carved in ivory, but classical gems were the most common adornments to the shrines, book covers, and reliquaries of the Middle Ages. These were embellished on works of medieval art from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries. Such stunning gems were not used merely because they were beautiful or alluring. By the ninth century, the ancient art of bespoke gem carving was basically dead in the West, but there still remained many supplies of Roman material. So gems represented a link with the world of the Caesars, which the secular rulers of the Middle Ages were more ready to embrace than the Church. At the same time, the Church recognized the power of the protective and magical sigils and designs on many of the classical gems and took suitable precautions before inserting them into their new Christian settings. The use of ancient gems and how the Church carefully utilized former Pagan-themed items in their own works of art is a fascinating subject in its own right.

Some of these shrines and works of art are still intact, but unfortunately many have not survived the ravages of time. In England, after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the sixteenth century, cathedrals and monasteries were sacked, and their medieval art and treasuries were melted down, stolen, destroyed, sold, or hidden. One of the most famous and tragic examples of the destruction of a cathedral treasury in England took place at Canterbury Cathedral. Twenty-four carts were needed to transport its contents to the London Mint, which were broken up and melted down between the years 1536 and 1540.

Earlier, it would have been impossible to imagine that such a tragedy could have taken place—but, as the vagaries of history and fate have often shown, they do occur, leaving centuries of consequences and new questions in their wake. In France, the similar break-up of many valuable medieval works of art and treasuries occurred at the time of the French Revolution (1789). Most were never to be seen again. Other countries experienced similar losses.

Whenever we are fortunate enough to see stone carvings, wood carvings, or ivory, metal, or enameled works of art in a Gothic cathedral today, we marvel at the quality of the craftsmanship and the overall effects they create. Like a book in stone, we visually “read” and experience a cathedral accordingly.

Symbolic imagination had precedence over literacy

While few in medieval times could read, many were more “literate” insofar as being able to understand symbols than we are today. (33) Can we correctly “interpret” these buildings? Would we be as able to know their stories, meanings, and allegories as a medieval pilgrim might? Probably not to the same degree, to be sure. For that matter, were we ever meant to fully understand such visual iconography at any period? It is often best to accept some of it as simply a mystery—a perspective actually closer to that of the High Middle Ages. Experiencing symbolism was, and is, far more important than mere analysis of it. Mystery is a central component of all religious and spiritual paths. It indicates the acceptance of a sense of awe, wonder and humility before the Divine, however one would define it.

Indeed, who are we today to automatically assume we are more intelligent, evolved, or capable of understanding these extraordinary edifices than the medieval masons who built them? The same holds true for ancient sites all over the world. In spite of our tremendous scientific, technological, and other modern progress, there are still unanswered questions. Perhaps certain images found in the Gothic cathedrals will, in time, be more clearly understood—or, hopefully, more deeply experienced. We seek an awakening of the hearts of those who see them, an increase of joy and awareness through the aesthetic beauty of these objects—something than anyone can connect with, be they spiritually inclined or not. Beauty is a universal concept.

An artistic sculpture of the ancient god Pan, here portrayed with his famed panpipes, by UK artist Rosa Davis, 2007

“In the case of the Gothic masters it is possible that it was the practice of their art—the devotion of their powers of attention in sculpting and carving and in the application of geometry to the service of a new vision of light and space—that enabled them to find the source of inspiration ...” (34)

And one of these sources of inspiration is, strangely enough, the more unusual grotesques, gargoyles, and Green Man images found in many of the great Gothic cathedrals, chapels and buildings all over western Europe.

Gargoyles, Grotesques and The Green Man

“Why are gargoyles and grotesques in a cathedral at all?” many today might ask. Others might ask, “and why not?” And, in particular, how were they approved by the committee as designs, especially by the chief cleric in charge? Such questions are quite normal considering the profusion of such images on and in the Gothic cathedrals.

From the twelfth century on, it became customary to decorate churches, cathedrals, and university colleges with carvings of an extraordinary diversity and creativity. Yet these figures often have what is called by art historians a “grotesque” character; i.e, they are images that portray humor, wit, horror, reverse imagery, or other unusual concepts. We can understand angels, of course, but why were demons and dragons and other images portrayed on churches of the very religion that had tried to subdue them? In the mindset of the medieval church, they served their own educational purpose for a higher end. And, they remained ever so popular with the masses.

A gargoyle on the Basilica of the Sacré Creur in Paris, clearly showing the water channel along the creature's back (Michael Reeve, WMC)

Gargoyle in Agia Napa Monastery in Cyprus (Julez A., WMC)

A fired and painted ceramic waterspout, 5th century BCE, in the Archaeological Museum of Delphi (Millevache, WMC)

Gargoyle in the Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Appoigny, France (Convivial94, WMC)

St. Bonifatius Church in Fulda, Germany (Markus, WMC)

Gargoyle at Rosslyn Cathedral (Karen Ralls)

What is a “gargoyle”? And how is it different from a “grotesque”?

A gargoyle is a spout usually carved in the shape of a demon-like dragon figure, often with wings. It is connected to a gutter for throwing rainwater from the roof of a building. Thus, most gargoyles are found on or near the roof. Linguists believe that the word “gargoyle” comes from the Middle English gargoyl, which came from the Middle French gargouille, akin to the Middle French gargouiller (13th century), and from the same root word from which we derived English words such as “gurgle,” “gullet,” “gully,” and “gulp.” Some gargoyles are rather simple in design; others are more elaborate, such as those seen on the exterior of Notre Dame de Paris.

A grotesque is a decorative carving taken from many themes relating to animals, birds, dragons, satyrs, mermaids, serpents, and so on. They can also feature fascinating hybrid creatures, i.e., half human/half animal figures, the Green Man, or entirely mythical creatures like unicorns. The clergy in certain areas did not necessarily appreciate including such wondrous visual diversity—often imagery that had roots in their own country or region's folklore traditions, or from the ancient world—yet they tolerated far more frightening and overtly demonic creatures from Hell in other carvings!

Some cathedrals have blatantly Pagan themes in a number of their carvings: for example, the Cathedral of Worms in Germany has displayed along one wall the illustrious heroes of the Nibelun-genlied, even though official theology claims they are merely “evil” or “demonic.” Technically speaking, according to architects, grotesques serve no practical purpose, as opposed to gargoyles and their rather mundane function as waterspouts. However, even here there are exceptions. For example, at the Washington National Cathedral, grotesques serve a similar function as gargoyles, but by a different means. These grotesques “deflect water away from a wall by diverting it over their heads,” according to Wendy Gasch, author of the Guide to Gargoyles and other Grotesques at the Washington National Cathedral. (35) Art historians maintain that the ornamental grotesques include all fantastic architectural creatures. Drainage gargoyles are considered a specialized category of grotesques. In other words, “not all grotesques are gargoyles, but all gargoyles are grotesques.”

According to one legend, the use of the term gargouille arose in the seventh century. A dragon with membranous wings, a long reptilian neck, prominent claws, and a slender snout was said to inhabit a cave near Rouen in France, called La Gargouille. But the actual historical origin of gargoyles is not known for certain. Gargoyles and grotesques are often found near the entrance to ancient temples. Art historians and archaeologists are still cataloguing them. But today, when we hear the word “gargoyle,” most of us tend to think of the Middle Ages—and the strange beasts and “monsters” adorning Gothic cathedrals. (36)

Misericord of Wyvern, Great Malvern Priory. (Simon Brighton)

Wild men and Wyverns at Beverly Minster, St. Mary's Church. (WMC)

Bearded man with toothache misericord, Lincoln cathedral. (WMC)

Images of gargoyles are quite popular today—appearing on T-shirts, coffee mugs, and computer mouse mats—perhaps yet another example of “medieval mania” in action. If so, why? In order to have such popularity and continuity through the centuries, grotesques and gargoyles must symbolize something far deeper that the intuitive mind can perceive, rather than the more usual left brain perception. The successes of medieval-themed books and films like Excalibur, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, The Lord of the Rings, and other related projects are interesting to note. Gargoyles and grotesques, it seems, are everywhere, and, as many cathedral guides note, visitors do take note of them and, at some locales, often ask to see certain ones specifically.

Gargoyles in ancient temples worldwide are often portrayed as having a protective function, as alleged “vicious guardians” to keep evil away from a sacred building or area. So, the theory went, the more “evil-looking” the grotesques and gargoyles were, especially near the entrance, the more protection the building was believed to have.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that all of the medieval clergy tolerated such supposedly “demonic” images. There were many complaints in some quarters about such ornate “evil” or “monster-like” carvings in the sacred houses of God. For example, in 1125, Bernard of Clairvaux famously railed against such figures in stone:

What are these fantastic monsters doing in the cloisters under the very eyes of the brothers as they read? What is the meaning of these unclean monkeys, strange savage lions and monsters? To what purpose are here placed these creatures, half beast, half man? ... Of what use to the brothers reading piously in the cloisters are these ridiculous monstrosities, these prodigies of deformed beauty, these beautiful deformities? ... There on one body grow several heads, and several heads have one body; here a quadruped wears the head of a serpent and the head of a quadruped appears on the body of a fish.... Almighty God! If we are not ashamed of these unclean things, we should at least regret what we have spent on them. (37)

Bernard was essentially saying: What on earth did so-called “monsters” have to do with the monks' daily worship? Why did stone carvers continue to insist on such bizarre-but-expensive decorations? He also asked, as do many architects and developers today: “What are such designs actually costing me?” Preferring a far more austere style himself, he certainly had little sense of humor in this regard. But other Churchmen argued that humor, being natural to man, did indeed have its rightful place in the scheme of things and the worship of God, especially. They also argued that since the church had a duty to minister to the illiterate as well as to the learned, humor was one way of more easily explaining or expressing complex ideas.

Certainly, to the medieval mind, all kinds of symbolic relationships were possible. A pair of lovers might represent the marriage of reason and revelations, and a harvester with a sickle could represent both Time and Jesus in some contexts, or the classic medieval figure of Death in others. So while the monks, philosophers and churchmen debated, the stone carvers kept on carving, often having a good deal of fun in the process. Some English medieval cathedrals, such as at Selby, for instance, feature even more unusual concepts, such as a gargoyle in the form of a boat, not widely seen elsewhere. (38)

Green Man, an artwork in papier maché, by UK artist Rosa Davis.

Not only cathedrals have grotesques. For example, Oxford University has its roots in medieval times; its oldest surviving colleges date from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and were founded to improve the learning of the clergy. (39) The quadrangle, that essential feature of college architecture, doubtless evolved from the monastic cloister, and indeed, several colleges have cloisters of their own. It was natural that these buildings would be decorated with gargoyles and grotesques in the medieval Gothic manner. Oxford has many hundreds of ornate grotesque carvings—in the Bodleian Library and the university's numerous colleges and other buildings.

Norwich cathedral Green Man, gold leaf, on its cloisters ceiling

Gargoyles largely went out of fashion after the late medieval period ended in the early fifteenth century and the Renaissance began. The relatively recent Neo-Gothic revival in nineteenth century England during the Victorian era saw gargoyles emerge again, especially on stone buildings.

The Green Man

Contrast the images of gargoyles and grotesques in the cathedrals with the carved images of the Green Man, also found in many medieval churches. The Green Man is a symbol of a face of a man sprouting much foliage and greenery from his mouth. Often assumed to be a Pagan Celtic symbol and an important representation of the Lord of the Forest, Green Man imagery is not unique to Celtic lore alone. Green Man carvings are found in ancient Eastern temples, such as in Borneo, where he is the “Lord God of the Forest,” and in temples high in the Himalayas such as in Tibet and India. It is a universal theme. While most are Green Man images, (40) there are also some Green Lady images. Green Cats are also found in medieval English churches, especially in Yorkshire and at Temple Bruer in Lincolnshire. (41) Norwich cathedral in Norfolk, England, has its famed carved gold leaf Green Man, high up on its cloister ceiling.

Misericord, triple-faced Green Man at Cartmel Priory, Cumbria. (Simon Brighton)

A Green Man carving in the Lady Chapel of Rosslyn Cathedral. (Simon Brighton)

Kilpeck Romanesque church in the United Kingdom. Green Man, created in 1140, at the south portal entrance. (Karen Ralls)

Garway, and horned god Cernunnos image. (Simon Brighton)

The Green Man theme has very early roots: “Heads from the Lebanon and Iraq can be dated to the 2nd century CE, and there are early Romanesque heads in 11th century Templar churches in Jerusalem. From the 12th to the 15th centuries, heads appeared in cathedrals and churches across Europe....” (42) British Folklore Society scholar Jeremy Harte comments that “for all their differences in mood, these carvings give a common impression of something—someone—alive among the green buds of summer or the brown leaves of autumn. Green Men can vary from the comic to the beautiful, although often the most beautiful ones are the most sinister.” (43)

The Green Man archetype reinforces an attitude of reverence and respect for the cycles of Nature and is a cluster of many strands—including ancient tree myths. The Tree of Life and related foliage folk customs are found all over Europe—folk tales relating to a man of the greenwood, such as those of Herne, (44) Robin Hood's Cave at Cresswell Crags in England, (45) Gawain and the Green Knight, and others. The human “face” of the Green Man (or Green Lady) is highly symbolic of Nature ever alive and vibrant, in and around us daily.

The stone chapel with the largest number of Green Man images in all of medieval Europe is Rosslyn Chapel, near Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Rosslyn Chapel was built in late medieval times, begun in 1446, and is known for its many exquisite carvings. It has 103 Green Man carvings inside the chapel alone, and more on the outside of the building.

Medieval Bestiaries: “monstrous beasts,” strange to behold

Bestiaries are books with illustrations depicting real and mythological animals and plants, based on the Latin Physiologus (Brussels Bibl. Roy. MS 10074). They are often considered to be a system of mystic zoology. Creatures real and imaginary appear in medieval bestiary manuscripts and in some cathedral carvings, ranging from birds, beasts, fishes, unicorns, dragons, serpents and other composite “monsters.” (46) More recently, the groundbreaking research on medieval Bestiaries by Courtauld Institute art historian Ron Baxter has determined that the Middle Ages had no category of zoology per se. The primary consumers of Bestiary manuscripts were not medieval monasteries, as might be expected, but more secular and scientific groups such as the lively court of Frederick II. (47)

Art of Memory and Grotesques:

The craft of what was called the meditative art of memory, memoria, “requires energizing devices to put it in gear and to keep it interested and on track, by arousing emotions of fear or delight, anger, wonder and awe.” (48) Many have felt that walking around a medieval cathedral or building is also a kind of quiet visual meditation, something that aids in concentration and connecting more deeply with spirituality. Perhaps, as some art historians maintain, a major function of the more dramatic grotesques in such buildings was to “jolt” the viewer visually, to startle his or her consciousness in some way and get him thinking:

Can memory be one possible explanation of the medieval love of the grotesque, the idiosyncratic? ... Is the proliferation of new imagery in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries related to the renewed emphasis on memory by the scholastics? I have tried to suggest that this is almost certainly the case. (49)

Grotesques do tend to be, “witty fun, it gets attention, it gets one started, perhaps off to heavenly things ... These ornaments delight the cellula deliciarum of inventive memoria, encouraging us to construct and ‘gather up’ increasingly complex things from our own knowledge stores.” (50) The grotesques “are fearful monsters, and self-generated anxiety and fear are a common beginning to meditation. Yet they are also often amusing ... the outrageous combinations that make up a medieval grotesque can shock (or humor) a reader into remembering that his own task is also actively fictive, and that passive receptivity will lead to mental wandering and getting ‘off the track.’” (51) Indeed, sometimes the more dramatic images, both positive or negative, in a film, book, or movie are those that “jolt” the viewer all the more, transporting him or her into another state of awareness; it was much the same with some of the images in a medieval cathedral.

Gargoyles and grotesques: the “beauty” of the macabre

Above all, as some historians and archaeologists have pointed out, gargoyles and grotesques gave a rather superb opportunity for unique expression to the stone carvers, “as their often fabulous work—terrifying, comic, bawdy, macabre, and rarely very ‘holy’—attests.” (52) Indeed, it might be said, “no stone was left unturned” by the guilds to create stunning, high quality carvings, and we witness the results of this superb craftsmanship today.

The medieval mind was preoccupied with the symbolic nature of the world of appearances; as everywhere “the visible seemed to reflect the invisible.” (53) Imagination was key, and Beauty, a universal concept, could also be seen in the eye of the macabre, the seemingly frightening, as much as in the beautiful or numinous, by the pilgrim or traveler, an odyssey all its own. (54)

Let us now pick up our staffs and begin our journey “on the road.” In the next chapter, we will explore more about medieval secular travel and sacred pilgrimage.