Best of Italy - Rick Steves (2016)

Practicalities

TOURIST INFORMATION

The Italian national tourist offices in the US offer many brochures and a free, general Italy guide. Before your trip, scan their website (www.italia.it) or contact the nearest branch if you have specific questions (New York—tel. 212/245-5618, newyork@enit.it; Chicago—tel. 312/644-0996, chicago@enit.it; Los Angeles—tel. 310/820-1898, losangeles@enit.it).

In Italy, a good first stop in every town is the tourist information office (abbreviated TI in this book). Prepare a list of questions and a proposed plan to double-check. Pick up a city map, confirm opening hours of sights, and get information on public transit (including bus and train schedules), walking tours, special events, and nightlife.

TRAVEL TIPS

Time Zones: Italy, like most of continental Europe, is generally six/nine hours ahead of the East/West Coasts of the US. The exceptions are the beginning and end of Daylight Saving Time: Europe “springs forward” the last Sunday in March (two weeks after North America), and “falls back” the last Sunday in October (one week before North America). For an online converter, try www.timeanddate.com/worldclock.

Business Hours: Some businesses respect the afternoon siesta; when it’s 90 degrees in the shade, you’ll understand why. Shops are generally open from 9:00 to 13:00 and from 16:00 to 19:30, daily except Sunday, though in touristy places, many stores stay open throughout the day and on Sunday, too. Banking hours are generally Monday through Friday 8:30 to 13:30 and 15:30 to 16:30. Most museums stay open all day; smaller ones may close for a siesta. On Sundays, sights are generally open, while public transportation options are fewer (for example, less bus service between towns).

Discounts: This book lists only the full adult price for sights. However, many sights offer discounts for youths (up to age 18), students (with proper identification cards, www.isic.org), families, and seniors (loosely defined as retirees or those willing to call themselves seniors). Always ask. Italy’s national museums generally offer free admission to anyone under 18, though some discounts are only available for citizens of the European Union.

Tobacco Shops: Tobacco shops (tabacchi, often indicated with a big T sign) are ubiquitous across Italy as handy places to get stamps, pay for street parking, and buy tickets for city buses and subways.

Online Translation: The Google Translate app converts spoken English into most European languages (and vice versa) and can also translate text it “reads” with your mobile device’s camera. To translate websites, use Google’s free Chrome browser (www.google.com/chrome) or paste the URL of the site into the translation window at www.google.com/translate.

HELP!

Emergency and Medical Help

Dial 113 for English-speaking police help. To summon an ambulance, call 118. Or ask at your hotel for help—they’ll know the nearest medical and emergency services. If you get a minor ailment, do as the locals do and go to a pharmacist for advice.

Drivers: For road service, call 116.

Theft or Loss

To replace a passport, you’ll need to go in person to an embassy or consulate office (listed below). If your credit and debit cards disappear, cancel and replace them. If your things are lost or stolen, file a police report, either on the spot or within a day or two; you’ll need it to submit an insurance claim for rail passes and travel gear, and it can help with replacing your passport and credit and debit cards. For more information, see www.ricksteves.com/help.

Damage Control for Lost Cards

If you lose your credit, debit, or ATM card, you can stop people from using your card by reporting the loss immediately to your card company. Call these 24-hour US numbers collect: Visa (tel. 303/967-1096), MasterCard (tel. 636/722-7111), and American Express (tel. 336/393-1111). In Italy, to make a collect call to the US, dial 800-172-444; press zero or stay on the line for an English-speaking operator. Visa’s and MasterCard’s websites list European toll-free numbers by country.

Avoiding Theft and Scams

With sweet-talking con artists at the train station, pickpockets on buses, and thieving gangs of children roving ancient sites, tourists face a gauntlet of rip-offs. Fortunately, violent crime is rare. Pickpockets don’t want to hurt you; they just want your money and gadgets.

My recommendations: Stay alert and wear a money belt (tucked under your clothes) to keep your cash, debit card, credit card, and passport secure; carry only the money you need for the day in your front pocket.

Treat any disturbance (e.g., someone bumps into you or spills something on you) as a smoke screen for theft. Be on guard while boarding and leaving crowded buses and subways. Thieves target tourists overloaded with bags or distracted with smartphones.

The sneakiest thieves dress as well-dressed businessmen or even tourists. The scruffy beggars on the street are easy to spot: fast-fingered moms with babies, and gangs of scruffy children holding up newspapers or cardboard signs to confuse their victims. They’ll scram like stray cats if you’re on to them.

Scams abound. When paying for something, be aware of how much cash you’re handing over (even state the denomination of the bill when paying a cabbie), demand clear and itemized bills at restaurants, and count your change. If self-proclaimed “police” on the street warn you about counterfeit (or drug) money, and ask to see your cash, don’t give them your wallet. Just say no to locals who want to “help” you use self-service machines that require your credit card for payment (for train tickets, parking, and so on). For advice on using cash machines smartly, read “Security Tips” under “Cash,” later.

There’s no need to be scared; just be smart and prepared.

If you report your loss within two days, you typically won’t be responsible for any unauthorized transactions on your account, although many banks charge a liability fee of $50. You can generally receive a temporary replacement card within two or three business days in Europe.

Embassies and Consulates

US Embassy in Rome: Tel. 06-4674-2420, 24-hour emergency tel. 06-46741 (visit by appointment only, Via Vittorio Veneto 121, http://italy.usembassy.gov)

US Consulates: in Milan—tel. 02-290-351 (Via Principe Amedeo 2/10, http://milan.usconsulate.gov); in Florence—tel. 055-266-951 (Lungarno Vespucci 38, http://florence.usconsulate.gov); in Naples—tel. 081-583-8111 (Piazza della Repubblica, http://naples.usconsulate.gov)

Canadian Embassy in Rome: Tel. 06-854-442-911 (Via Zara 30, www.italy.gc.ca)

Canadian Consulate in Milan: Tel. 02-626-94238 (Piazza Cavour 3, www.italy.gc.ca)

MONEY

This section offers advice on how to pay for purchases on your trip (including getting cash from ATMs and paying with plastic), VAT (sales tax) refunds, and tipping.

Exchange Rate

1 euro (€) = about $1.10

To convert prices in euros to dollars, add about 10 percent: €20=about $22; €50=about $55. (Check www.oanda.com for the latest exchange rates.) Just like the dollar, one euro is broken down into 100 cents. Coins range from €0.01 to €2, and bills from €5 to €500 (though bills over €50 are rarely used).

What to Bring

Bring both a credit card and a debit card. You’ll use the debit card at cash machines (ATMs) to withdraw local cash for most purchases, and the credit card to pay for larger items. Some travelers carry a third card as a backup, in case one gets demagnetized or eaten by a rogue machine.

For an emergency stash, bring several hundred dollars in hard cash in $20 bills. If you have to exchange the bills, go to a bank; avoid using currency-exchange booths because of their lousy rates and/or outrageous (and often hard-to-spot) fees.

Cash

Cash is just as desirable in Europe as it is at home. Small businesses (mom-and-pop cafés, shops, etc.) prefer that you pay your bills with cash. Some vendors will charge you extra for using a credit card, some won’t accept foreign credit cards, and some won’t take any credit cards at all. Cash is the best—and sometimes only—way to pay for cheap food, bus fare, taxis, sights, and local guides.

Throughout Europe, ATMs are the standard way for travelers to get cash. They work just like they do at home. To withdraw money from an ATM (called a bancomat in Italy), you’ll need a debit card (ideally with a Visa or MasterCard logo for maximum usability), plus a PIN code (numeric and four digits). Although you can use a credit card to withdraw cash at an ATM, this comes with high bank fees and only makes sense in an emergency.

Security Tips: Shield the keypad when entering your PIN code. When possible, use ATMs located outside banks—a thief is less likely to target a cash machine near surveillance cameras, and if you have trouble with the transaction, you can go inside for help.

Don’t use an ATM if anything on the front of the machine looks loose or damaged (a sign that someone may have attached a “skimming” device to capture account information). If a cash machine eats your card, check for a thin plastic insert with a tongue hanging out (thieves use these devices to extract cards).

Stay away from “independent” ATMs, such as Travelex, Euronet, YourCash, Cardpoint, and Cashzone, which charge huge commissions and have terrible exchange rates, and may try to trick users with “dynamic currency conversion” (described at the end of “Credit and Debit Cards,” next).

If you want to monitor your accounts online during your trip to detect any unauthorized transactions, be sure to use a secure connection (see here).

Credit and Debit Cards

For purchases, Visa and MasterCard are more commonly accepted than American Express. Just like at home, credit or debit cards work easily at larger hotels, restaurants, and shops. I typically use my debit card to withdraw cash to pay for most purchases.

I use my credit card sparingly: to book hotel reservations, to buy advance tickets for events or sights, to cover major expenses (such as car rentals or plane tickets), and to pay for things online or near the end of my trip (to avoid another visit to the ATM). While you could instead use a debit card for these purchases, a credit card offers a greater degree of fraud protection.

Ask Your Credit- or Debit-Card Company: Before your trip, contact the company that issued your debit or credit cards.

✵ Confirm your card will work overseas, and alert them that you’ll be using it in Europe; otherwise, they may deny transactions if they perceive unusual spending patterns.

✵ Ask for the specifics on transaction fees. When you use your credit or debit card—either for purchases or ATM withdrawals—you’ll typically be charged additional “international transaction” fees of up to 3 percent (1 percent is normal) plus $5 per transaction. If your card’s fees seem high, consider getting a different card just for your trip: Capital One (www.capitalone.com) and most credit unions have low-to-no international fees.

✵ Verify your daily ATM withdrawal limit, and if necessary, ask your bank to adjust it. Some travelers prefer a high limit that allows them to take out more cash at each ATM stop (saving on bank fees), while others prefer to set a lower limit in case their card is stolen. Note that foreign banks also set maximum withdrawal amounts for their ATMs.

✵ Get your bank’s emergency phone number in the US (but not its 800 number, which isn’t accessible from overseas) to call collect if you have a problem.

✵ Ask for your credit card’s PIN in case you need to make an emergency cash withdrawal or encounter Europe’s chip-and-PIN system; the bank won’t tell you your PIN over the phone, so allow time for it to be mailed to you.

Magnetic-Stripe versus Chip-and-PIN Credit Cards: Europeans are increasingly using chip-and-PIN credit cards embedded with an electronic security chip and requiring a four-digit PIN. Your American-style card (with just the old-fashioned magnetic stripe) will work fine in most places. But there could be minor inconveniences; it might not work at unattended payment machines, such as those at train and subway stations, toll plazas, parking garages, bike-rental kiosks, and gas pumps. If you have problems, try entering your card’s PIN, look for a machine that takes cash, or find a clerk who can process the transaction manually.

No matter what kind of card you have, it pays to carry euros, and remember, you can always use an ATM to withdraw cash with your magnetic-stripe debit card.

Dynamic Currency Conversion: If merchants or hoteliers offer to convert your purchase price into dollars (called dynamic currency conversion, or DCC), refuse this “service.” You’ll pay even more in fees for the expensive convenience of seeing your transaction in dollars. If your receipt shows the total in dollars only, ask for the transaction to be processed in euros. If the clerk refuses, pay in cash. Similarly, if an ATM offers to “lock in” or “guarantee” your conversion rate, choose “proceed without conversion” and opt for euros over dollars.

Tipping

Tipping in Italy isn’t as automatic and generous as it is in the US. For special service, tips are appreciated, but not expected. As in the US, the right amount depends on your resources and the circumstances, but some general guidelines apply.

Restaurants: In Italy, a service charge (servizio) is usually built into your bill, so the total you pay already includes a basic tip. If you tip extra for good service, you could include €1-2 for each person in your party (generally that comes to about 5 percent of the bill); for details, see here.

Taxis: Round up your fare a bit (for instance, if the fare is €4.50, pay €5). If the cabbie hauls your bags and zips you to the airport to help you catch your flight, you might want to toss in a little more. But if you feel like you’re being driven in circles or otherwise ripped off, skip the tip.

Services: In general, if someone in the service industry does a super job for you, a small tip of a euro or two is appropriate...but not required. If you’re not sure whether (or how much) to tip for a service, ask a local for advice.

Getting a VAT Refund

Wrapped into the purchase price of your Italian souvenirs is a Value-Added Tax (VAT) of about 22 percent. You’re entitled to get most of that tax back if you purchase more than €155 (about $170) worth of goods at a store that participates in the VAT-refund scheme. Typically, you must ring up the minimum at a single retailer—you can’t add up your purchases from various shops to reach the required amount.

If the merchant ships the goods to your home, the tax will be subtracted from your purchase price. Otherwise, you’ll need to:

Get the paperwork. Have the merchant completely fill out the necessary refund document. You’ll have to present your passport. Get the paperwork done before you leave the store to ensure you’ll have everything you need (including your original sales receipt).

Get your stamp at the border or airport. Process your VAT document at your last stop in the European Union (the airport or border) with the customs agent who deals with VAT refunds. Arrive an additional hour before you need to check in for your flight to allow time to find the customs office and wait in line. It’s best to keep your purchases in your carry-on. But if they’re too large or dangerous to carry on (such as knives), pack them in your checked bags and alert the check-in agent. You’ll be sent (with your tagged bag) to a customs desk outside security; someone will examine your bag, stamp your paperwork, and put your bag on the belt. You’re not supposed to use your purchased goods before you leave. If you show up at customs wearing your new Italian leather shoes, officials might look the other way—or deny you a refund.

Collect your refund. You’ll need to return your stamped document to the retailer or its representative. Many merchants work with services—such as Global Blue or Premier Tax Free—that have offices at major airports, ports, or border crossings (either before or after security). These services, which extract a 4 percent fee, can refund your money immediately in cash or credit your card (within two billing cycles). If the retailer handles VAT refunds directly, it’s up to you to contact the merchant for your refund. You can mail the documents from home or from your point of departure. You’ll then have to wait—it can take months.

Customs for American Shoppers

You are allowed to take home $800 worth of items per person duty-free, once every 31 days. You can take home many processed and packaged foods: vacuum-packed cheeses, dried herbs, jams, baked goods, candy, chocolate, oil, vinegar, mustard, and honey. Fresh fruits and vegetables and most meats are not allowed, with exceptions for some canned items.

You can bring home one liter of alcohol duty-free. It can be packed securely in your checked luggage, along with any other liquid-containing items. But if you want to pack the alcohol (or any liquid-packed food) in your carry-on bag for your flight home, buy it at a duty-free shop at the airport.

For details on allowable goods, customs rules, and duty rates, visit http://help.cbp.gov.

SIGHTSEEING

Sightseeing can be hard work. Use these tips to make your visits to Italy’s finest sights meaningful, fun, efficient, and painless.

Plan Ahead

Set up an itinerary that allows you to fit in all your must-see sights. For a one-stop look at opening hours, see the “At a Glance” sidebars in this book for each major destination. Most places keep stable hours, but you can confirm the latest at the TI or by checking museum websites. Many museums are closed or have reduced hours at least a few days a year, especially on major holidays. In summer, some sights stay open late. Off-season, many museums have shorter hours. Whenever you go, don’t put off visiting a must-see sight—you never know if a place will close unexpectedly for a holiday, strike, or restoration.

Several cities, including Venice, Florence, and Rome, offer sightseeing passes that cover many (but not all) museums. Do the math: Add up the entry costs of the sights you want to see to figure out if a pass will save you money. An added bonus is that passes allow you to bypass the long ticket-buying lines at popular sights; that alone can make a pass worthwhile.

Sometimes you can avoid lines by making reservations for an entry time (for example, at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery or Rome’s Vatican Museums). At some popular places (such as Venice’s Doge’s Palace), you can get in more quickly by buying your ticket or pass at a less-crowded sight nearby (Venice’s Correr Museum). Several sights require reservations, such as Rome’s Borghese Gallery and Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan. If you haven’t reserved ahead, taking a guided tour can help you skip lines at some sights, such as the Last Supper or the Uffizi. Specifics appear in the chapters.

If you can’t reserve a popular sight, try visiting very early or very late. When available, evening visits are usually peaceful, with fewer crowds.

Study up. To get the most out of the sight descriptions in this book, read them before you visit. That said, every sight or museum offers more than what is covered in this book. Use the information in this book as an introduction—not the final word.

At Sights

Here’s what you can typically expect:

Entering: Be warned that you may not be allowed to enter if you arrive 30-60 minutes before closing time. And guards start ushering people out well before the actual closing time, so don’t save the best for last.

Some important sights have a security check, where you must open your bag or send it through a metal detector. Some sights require you to check daypacks and coats. (If you’d rather not check your daypack, try carrying it tucked under your arm like a purse as you enter.)

Photography: If the museum’s photo policy isn’t clearly posted, ask a guard. Generally, taking photos without a flash or tripod is allowed. Some sights ban photos altogether.

Temporary Exhibits: Museums may show special exhibits in addition to their permanent collection. Some exhibits are included in the entry price, while others cost extra (which you might have to pay even if you don’t visit the exhibit).

Expect Changes: Artwork can be on tour, on loan, out sick, or shifted at the whim of the curator. Pick up a floor plan as you enter, and ask the museum staff if you can’t find a particular item. Say the title or artist’s name, or point to the photograph in this book and ask, “Dov’è?” (doh-VEH, meaning “Where is?”).

Audioguides and Apps: Many sights rent audioguides, which generally offer excellent recorded descriptions of the art in English. If you bring your own earbuds, you can enjoy better sound. A growing number of sights offer apps (often free) that you can download to your mobile device—check their websites. I’ve produced free, downloadable audio tours for some of Italy’s major sights; these are indicated in this book with the symbol ![]() . For more on my audio tours, see here.

. For more on my audio tours, see here.

Dates for Artwork: It helps to know the terms. Art historians and Italians refer to the great Florentine centuries by dropping 1,000 years. The Trecento (300s), Quattrocento (400s), and Cinquecento (500s) are the 1300s, 1400s, and 1500s. The Novecento (900s) means modern art (the 1900s). In Italian museums, art is dated with sec for secolo (century, often indicated with Roman numerals), a.c. (avanti Cristo, or b.c.), and d.c. (dopo Cristo, or a.d.). OK?

Services: Major sights may have an on-site café or cafeteria, usually a good place to rejuvenate during a long visit. The WCs at sights are free and generally clean.

Before Leaving: At the gift shop, scan the postcard rack or thumb through a guidebook to be sure that you haven’t overlooked something that you’d like to see.

At Churches

Remember that a modest dress code (no bare shoulders or shorts for anyone, including children) is enforced at the famous churches, such as Vatican’s St. Peter’s and Venice’s St. Mark’s, but is often relaxed in other churches. If needed, you can improvise, using maps to cover your shoulders and a jacket for your knees. (I wear a super-lightweight pair of long pants rather than shorts for my hot and muggy big-city Italian sightseeing.)

Some churches have coin-operated audioboxes that describe the art and history; just set the dial on English, put in your coins, and listen. Coin boxes near a piece of art illuminate the art, presenting a better photo opportunity. I pop in a coin whenever I can. Let there be light.

SLEEPING

I favor hotels and restaurants that are handy to your sightseeing activities. Rather than list hotels scattered throughout a city, I choose hotels in my favorite neighborhoods.

Book your accommodations well in advance, particularly if you’ll be traveling during holidays or peak season (May-Oct in northern Italy, and May-June and Sept-Oct in southern Italy). See here for a list of major holidays and festivals in Italy; for tips on making reservations, see here.

Rates and Deals

I’ve described my recommended accommodations using a Sleep Code (see sidebar). The prices I list are for one-night stays in peak season, and assume you’re booking directly with the hotel (not through an online hotel-booking engine or TI). Booking services extract a commission from the hotel, which logically closes the door on special deals. Book direct.

My recommended hotels each have a website (often with a built-in booking form) and an email address; you can expect a response in English within a day and often sooner.

Sleep Code

Price Rankings

To help you easily sort through my listings, I’ve divided the accommodations into three categories based on the price for a basic double room with bath during peak season:

|

$$$ |

Higher Priced |

|

$$ |

Moderately Priced |

|

$ |

Lower Priced |

Prices can change without notice; verify the hotel’s current rates online or by email. For the best prices, always book directly with the hotel.

Abbreviations

I use the following code to describe accommodations in this book. Prices listed are per room, not per person. When a price range is given for a type of room (such as double rooms listing for €100-150), it means the price fluctuates with the season, size of room, or length of stay; expect to pay the upper end for peak-season stays.

|

S |

= |

Single room (or price for one person in a double). |

|

D |

= |

Double or twin room. “Double beds” can be two twins sheeted together and are usually big enough for nonromantic couples. |

|

T |

= |

Triple (generally a double bed with a single). |

|

Q |

= |

Quad (usually two double beds; adding an extra child’s bed to a T is usually cheaper). |

|

b |

= |

Private bathroom with toilet and shower or tub. |

According to this code, a couple staying at a “Db-€140” hotel would pay a total of €140 (about $155) for a double room with a private bathroom. Unless otherwise noted, breakfast is included, hotel staff speak basic English, credit cards are accepted, and hotels have a guest computer and/or Wi-Fi.

A variable city tax of €1.50-5/person per night (usually payable by cash only) is often added to hotel bills, and is not included in the prices in this book.

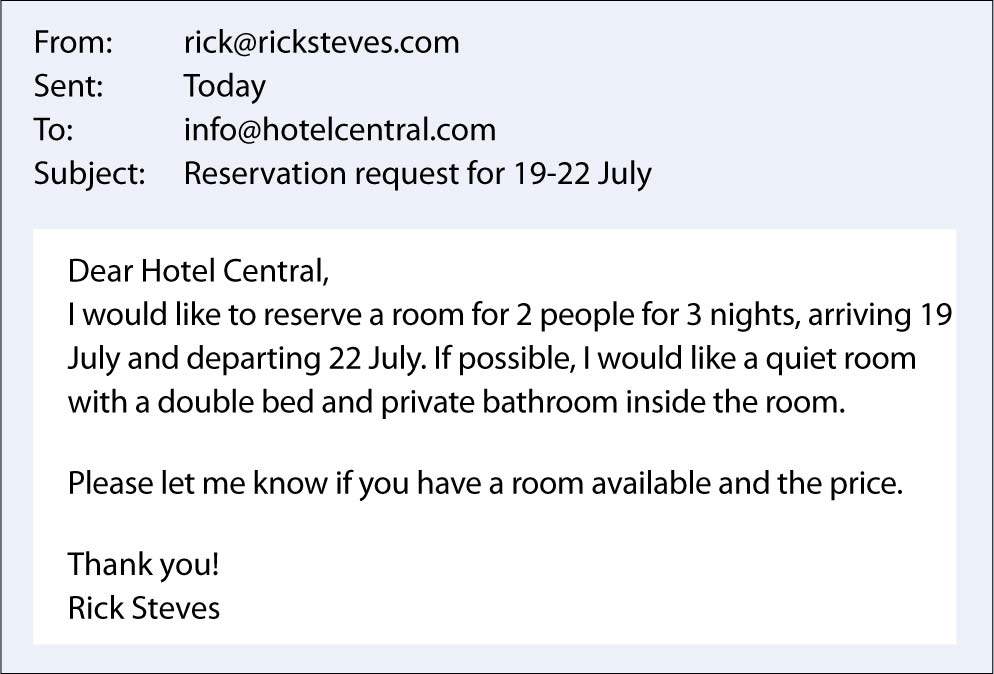

Making Hotel Reservations

Reserve your rooms several weeks in advance—or as soon as you’ve pinned down your travel dates. Note that some national holidays merit your making reservations far in advance (see here).

Requesting a Reservation: It’s easiest to book your room through the hotel’s website. (For the best rates, always use the hotel’s official site and not a booking agency’s site.) If there’s no reservation form, or for complicated requests, send an email (see opposite page for a sample request). Most recommended hotels take reservations in English.

The hotelier wants to know:

✵ the number and type of rooms you need

✵ the number of nights you’ll stay

✵ your date of arrival (use the European style for writing dates: day/month/year)

✵ your date of departure

✵ any special needs (such as bathroom in the room or down the hall, cheapest room, twin beds vs. double bed, and so on)

Mention any discounts—for Rick Steves readers or otherwise—when you make the reservation.

Confirming a Reservation: Most places will request a credit-card number to hold your room. If they don’t have a secure online reservation form—look for the https—you can email it (I do), but it’s safer to share that confidential info via a phone call or two emails (splitting your number between them).

Canceling a Reservation: If you must cancel, it’s courteous—and smart—to do so with as much notice as possible, especially for smaller family-run places. Be warned that cancellation policies can be strict; read the fine print or ask about these before you book. Internet deals may require prepayment, with no refunds for cancellations.

Reconfirming a Reservation: Always call or email to reconfirm your room reservation a few days in advance. For smaller hotels, I call again on my day of arrival to tell my host what time I expect to get there (especially important if arriving late—after 17:00).

Phoning: For tips on how to call hotels overseas, see here.

If you’re on a budget, it’s smart to email several hotels to ask for their best price. Comparison-shop and make your choice. In general, prices can soften if you do any of the following: offer to pay cash, stay at least three nights, or mention this book. You can also try asking for a cheaper room or offer to skip breakfast.

Types of Accommodations

Hotels

Italians usually use the word hotel, but you might also see albergo or pensione. English works in all but the cheapest places.

If you’re heading south in summer, opt for a place with air-conditioning. It’s not always available in spring and fall. To conserve energy, the government enforces limits on air-conditioning and heating: There’s a one-month period each spring and fall when neither is allowed.

Most listed hotels have rooms for one to five people. Solo travelers find that the cost of a single room is often only 25 percent less than a double room. Three or four people can save money by requesting one big room. If there’s room for an extra cot, they’ll cram it in for you (charging you around €25).

Assume that breakfast is included in the prices I’ve listed, unless otherwise noted. If breakfast is optional, you may want to skip it. While convenient, it’s usually expensive—€5-8 per person for a continental buffet with (at its most generous) bread, ham, cheese, yogurt, and unlimited caffè latte. A picnic in your room followed by a coffee at the corner café can be cheaper.

Hotel bathrooms often include a bidet (which Italians use for quick sponge baths). The cord that dangles over the tub or shower is not a clothesline. You pull it when you’ve fallen and can’t get up.

If you’re arriving in the morning, your room probably won’t be ready. Drop your bag safely at the hotel and dive right into sightseeing.

When you check in, the receptionist will normally ask for your passport and keep it for anywhere from a couple of minutes to a couple of hours. Hotels are legally required to register each guest with the police. Relax. Americans are notorious for making this chore more difficult than it needs to be.

If you suspect night noise will be a problem (for instance, if you discover your room is over a nightclub), ask for a quieter room in the back or on an upper floor.

Hoteliers can be a great help and source of advice. Most know their cities well, and can assist you with everything from public transit and airport connections to finding a good restaurant, the nearest launderette, or a Wi-Fi hotspot.

The Good and Bad of Online Reviews

User-generated travel review websites—such as TripAdvisor, Booking.com, and Yelp—give you access to actual reports—good and bad—from travelers who have experienced the hotel, restaurant, tour, or attraction.

While these sites try hard to weed out bogus users, I’ve seen hotels “bribe” guests (for example, offer a free breakfast) in exchange for a positive review. Nor can you always give credence to negative reviews: Different people have different expectations.

A user-generated review is based on the experience of one person, who likely stayed at one hotel and ate at a few restaurants, and doesn’t have much of a basis for comparison. A guidebook is the work of a trained researcher who visited many alternatives to assess their relative value. When I’ve checked out top-rated TripAdvisor listings in various towns, I’ve found that some are gems but just as many are duds.

Guidebooks and review websites both have their place, and in many ways, they’re complementary. If a hotel or restaurant is well-reviewed in a guidebook, and also gets good ratings on one of these sites, it’s likely a winner.

Even at the best places, mechanical breakdowns occur: Air-conditioning malfunctions, sinks leak, hot water turns cold, and toilets gurgle and smell. Report your concerns clearly and calmly at the front desk. For more complicated problems, don’t expect instant results.

To guard against theft in your room, keep valuables out of sight. Some rooms come with a safe, and other hotels have safes at the front desk. I’ve never bothered using one.

Checkout can pose problems if surprise charges pop up on your bill. If you settle your bill the afternoon before you leave, you’ll have time to discuss and address any points of contention (before 19:00, when the night shift usually arrives).

Above all, keep a positive attitude. Remember, you’re on vacation. If your hotel is a disappointment, spend more time out enjoying the city you came to see.

Hostels

A hostel (ostello) provides cheap dorm beds for about €20-30 per night. Family or double rooms may be available on request. Travelers of any age are welcome. Most hostels offer kitchen facilities, guest computers, Wi-Fi, and a self-service laundry. Most hostels provide all bedding, including sheets.

There are two kinds of hostels: Independent hostels tend to be easygoing, colorful, and informal (no membership required); try www.hostelworld.com, www.hostelz.com, or www.hostels.com. Official hostels are part of Hostelling International (HI), share an online booking site (www.hihostels.com), and typically require that you either have a membership card or pay extra per night.

Other Accommodation Options

Renting an apartment, house, or villa can be a fun and cost-effective way to go local. Websites such as Booking.com, Airbnb, VRBO, and FlipKey let you browse properties and correspond directly with European property owners or managers. Airbnb and Roomorama also list rooms in private homes. Beds range from air-mattress-in-living-room basic to plush-B&B-suite posh.

Another option is Cross-Pollinate.com, an online booking agency representing B&Bs and apartments in some European cities, including Rome, Venice, and Florence (US tel. 800-270-1190, Italy tel. 06-9936-9799, www.cross-pollinate.com, info@cross-pollinate.com).

If you want a place to sleep that’s free, try Couchsurfing.org.

EATING

The Italians are masters of the art of fine living. That means eating long and well. Lengthy, multicourse meals and many hours sitting in outdoor cafés are the norm. Americans eat on their way to an evening event and complain if the check is slow in coming. For Italians, the meal is an end in itself, and only rude waiters would rush you.

In general, Italians eat lunch and dinner later than we do. At 7:00 or 8:00 in the morning, they have a light breakfast (coffee—usually cappuccino or espresso—and a pastry). Lunch (between 13:00 and 15:00) is traditionally the largest meal of the day. Then they eat a late, light dinner (around 20:00-21:30, or maybe earlier in winter). To bridge the gap, people drop into a bar in the late afternoon for a snack.

Breakfast

The basic, traditional version is coffee and a roll with butter and marmalade. These days, many hotels also offer yogurt and juice, and possibly also cereal, ham, cheese, and hard-boiled eggs. Small budget hotels may leave a basic breakfast in a fridge in your room (croissant, roll, jam, yogurt, coffee). In general, the pricier the hotel, the bigger the breakfast.

If you want to skip your hotel breakfast, consider browsing for a morning picnic at a local open-air market. Or do as the Italians do: Stop into a bar or café to drink a cappuccino and munch a cornetto (croissant) while standing at the bar.

Restaurants

When restaurant-hunting, choose a spot filled with locals. Venturing even a block or two off the main drag leads to higher-quality food for less than half the price of the tourist-oriented places. Locals eat better at lower-rent locales.

Most restaurant kitchens close down between their lunch and dinner service. Good restaurants don’t reopen for dinner before 19:00. Small restaurants with a full slate of reservations for 20:30 or 21:00 often will accommodate walk-in diners willing to eat a quick, early meal, but you aren’t expected to linger.

For help in ordering, get a phrase book, such as the Rick Steves Italian Phrase Book & Dictionary, which has a menu decoder and plenty of useful phrases for navigating the culinary scene.

Cover and Tipping

Before you sit down, look at a menu to see what extra charges a restaurant tacks on. Two different items are routinely factored into your bill: the coperto and the servizio.

The coperto (cover charge), sometimes called pane e coperto (bread and cover), offsets the overhead expenses from the basket of bread on your table to the electricity running the dishwasher. It’s not negotiable, even if you don’t eat the bread. Think of it as the cost of using the table for as long as you like. Most restaurants add the coperto onto your bill as a flat fee (€1-3.50 per person; the amount should be clearly noted on the menu).

The servizio (service charge) of about 10 percent pays for the waitstaff. At most eateries, the words servizio incluso are written on the menu and/or the receipt, indicating that the listed prices already include the fee. You can add on a tip, if you choose, by including €1-2 for each person in your party. While Italians don’t think about tips in terms of percentages—and many don’t tip at all—this bonus amount usually comes out to about 5 percent (10 percent is excessive for all but the very best service).

A few restaurants tack on a 10 percent servizio charge to your bill. If a menu reads servizio 10%, the listed prices don’t include the fee; it will be added onto your bill for you (so you don’t need to calculate it yourself and pay it separately). Rarely, you’ll see the words servizio non incluso on the menu or bill; in this case, you’re expected to add a tip of about 10 percent.

When you want the bill, mime-scribble on your raised palm or request it: “Il conto, per favore.” You may have to ask for it more than once. If you’re in a hurry, request the check when you receive the last item you order.

Courses: Antipasto, Primo, and Secondo

A full Italian meal consists of several courses, though you’re not obliged to get it all:

Antipasto: An appetizer such as bruschetta, grilled veggies, deep-fried tasties, thin-sliced meat (such as prosciutto or carpaccio), or a plate of olives, cold cuts, and cheeses.

Primo piatto: A “first dish” generally consisting of pasta, rice, or soup. If you think of pasta when you think of Italy, you can dine well without ever going beyond the primo.

Secondo piatto: A “second dish,” equivalent to our main course, of meat or fish/seafood. A vegetable side dish (contorno) may come with the secondo but more often must be ordered separately.

Restaurant Strategy: For most travelers, a meal with all three courses (plus contorni, dessert, and wine) is simply too much food—and euros can add up in a hurry. To avoid overeating and to stretch your budget, share dishes. A good rule of thumb is for each person to order any two courses. For example, a couple can order and share one antipasto, one primo, one secondo, and one dessert; or two antipasti and two primi; or whatever combination appeals.

Another good option is sharing an array of antipasti—either by ordering several specific dishes or, at restaurants that offer self-serve buffets, by choosing a variety of cooked appetizers from an antipasti buffet spread out like a salad bar. At buffets, you pay per plate; a typical serving costs about €8. Generally Italians don’t treat buffets as all-you-can-eat, but take a one-time moderate serving; watch other customers and follow their lead.

Ordering Your Food

Seafood and steak may be sold by weight (priced by the kilo—1,000 grams, or just over two pounds; or by the etto—100 grams). The abbreviation s.q. (secondo quantità) means an item is priced “according to quantity.” Unless the menu indicates a fillet (filetto), fish is usually served whole, with the head and tail. However, you can always ask your waiter to select a small fish for you. Sometimes, especially for steak, restaurants require a minimum order of four or five etti (which diners can share). Make sure you’re clear on the price before ordering.

Some special dishes come in larger quantities meant to be shared by two people. The shorthand way of showing this on a menu is “X2” (for two), but the price listed generally indicates the cost per person.

In a traditional restaurant, if you order a pasta dish and a side salad—but no main course—the waiter will bring the salad after the pasta (Italians prefer it this way, believing that it enhances digestion). If you want the salad with your pasta, specify insieme (een-see-YEH-meh; together). At eateries accustomed to tourists, you may be asked when you want the salad.

At places with counter service—such as at a bar or a freeway rest-stop diner—you’ll order and pay at the cassa (cashier). Take your receipt over to the counter to claim your food.

Fixed-Price Meals

You can save by getting a fixed-priced meal, which is frequently exempt from cover and service charges. Avoid the cheapest ones (often called a menù turistico), which tend to be bland and heavy, pairing a basic pasta with reheated meat. Look instead for a genuine menù del giorno (menu of the day), which offers diners a choice of appetizer, main course, and dessert. It’s worth paying a little more for an inventive fixed-price meal that shows off the chef’s creativity. While fixed-price meals can be easy and convenient, galloping gourmets prefer to order à la carte.

Budget Eating

Italy offers many budget options for hungry travelers, but beware of cheap eateries that sport big color photos of pizza and piles of different pastas. They simply microwave prepackaged food.

Pizza Shops

Pizzerias are ubiquitous and affordable, though even cheaper is a hole-in-the-wall takeout pizza shop. Some shops sell takeout Naples-style pizza whole or by the slice (al taglio). Others offer pizza rustica (thick pizza baked in a big rectangular pan) by the weight, in which case you indicate how much you want: 100 grams, or un etto, is a hot and cheap snack; 200 grams, or due etti, makes a light meal. Or show the size with your hands—tanto così (TAHN-toh koh-ZEE; this much).

Bars / Cafés

Italian “bars” are not taverns, but inexpensive cafés. These neighborhood hangouts serve coffee, minipizzas, sandwiches, and drinks from the cooler. This budget choice is the Italian equivalent of English pub grub.

Many bars are small—if you can’t find a table, you’ll need to stand or find a ledge to sit on outside. Most charge extra for table service. To get food to go, say, “da portar via” (for the road). All bars have a WC (toilette, bagno) in the back, and customers—and the discreet public—can use it.

Food: For quick meals, bars usually have trays of cheap, premade sandwiches (panini or piadini on baguettes or flatbread; or tramezzini on crustless white bread). Some sandwiches are delightful grilled, but some have too much mayo. To save time for sightseeing and room for dinner, stop by a bar for a light lunch, such as a ham-and-cheese sandwich (called toast). For heartier fare, you can choose a premade meal (from the glass display case) that they’ll reheat for you.

Prices and Paying: Bars have a two- or three-tiered pricing system. Drinking a cup of coffee while standing at the bar is cheaper than drinking it at an indoor table; you’ll pay still more at an outdoor table. Many places have a lista dei prezzi (price list) with two columns—al bar and al tavolo (table)—posted somewhere by the bar or cash register. If you’re on a budget, don’t sit down without first checking out the financial consequences. You can ask, “Same price if I sit or stand?” by saying, “Costa uguale al tavolo o al banco?” (KOH-stah oo-GWAH-lay ahl TAH-voh-loh oh ahl BAHN-koh). Throughout Italy, you can get cheap coffee at the bar of any establishment, no matter how fancy, and pay the same low, government-regulated price (generally less than a euro if you stand).

If the bar isn’t busy, you can probably just order and pay when you leave. Otherwise: 1) Decide what you want; 2) find out the price by checking the prices posted near the food, the price list on the wall, or by asking the barista; 3) pay the cashier; and 4) give the receipt to the barista (whose clean fingers handle no dirty euros) and tell him or her what you want.

For more on drinking, see “Beverages,” later.

Ethnic Food

A good bet for a cheap, hot meal is a döner kebab (rotisserie meat wrapped in pita bread). Look for small kebab shops, where you can get a hearty, meaty takeaway dinner wrapped in pita bread for €3.50. Pay an extra euro to supersize it, and it’ll feed two. Asian restaurants, although not as common as in northern Europe, usually serve only Chinese dishes and can also be a good value.

Cafeterias, Rosticcerie, and Tavola Calda Bars

For a fast, cheap meal, these options offer the point-and-choose basics without add-on charges. Self-service cafeterias are as predictable in Italy as they are in your hometown.

Or try the Italian version of the corner deli: a rosticceria (specializing in roasted meats and accompanying antipasti) or a tavola calda bar (a “hot table” buffet spread of meat and vegetables). Belly up to the bar, and with a pointing finger, you can assemble a fine meal, such as lasagna, rotisserie chicken, and sides like roasted potatoes and spinach. If something’s a mystery, ask for un assaggio (oon ah-SAH-joh) to get a taste. To have your choices warmed up, ask for them to be heated (scaldare; skahl-DAH-ray). You can sometimes eat at tables or counters provided, or just get the food to go for a classy, filling picnic.

Wine Bars

Wine bars (enoteche) are popular, fast, and affordable for lunch. Surrounded by the office crowd, you can get a salad, a plate of meats (cold cuts) and cheeses, and a glass of good wine (see blackboards for the day’s selection and price per glass). A good enoteca aims to impress visitors with its wine, and will generally choose excellent-quality ingredients for the simple dishes it offers with the wine. Be warned: Prices add up—keep track of what you’re ordering to keep this a budget choice.

Aperitivo Buffets

The Italian term aperitivo means a pre-dinner drink, but it’s also used to describe their version of what we might call happy hour: a light buffet that many bars serve to customers during the pre-dinner hours (typically around 18:00 or 19:00 until 21:00). The drink itself may not be cheap (typically around €8-12), but bars lay out an array of meats, cheeses, grilled vegetables, and other antipasti-type dishes, and you’re welcome to nibble to your heart’s content while you nurse your drink. While it’s intended as an appetizer course before heading out for a full dinner, light eaters could discreetly turn this into a small meal. Drop by a few bars around this time to scope out their buffets before choosing.

Groceries and Markets

Picnicking saves lots of euros. Drop by a neighborhood grocery (alimentari), a supermercato (such as Conad, Despar, or Co-op), or an open-air market to pick up meats, cheeses, fresh rolls, and other picnic treats. Ordering 100 grams (un etto) of cheese or meat is about a quarter-pound, enough for two sandwiches. Yogurt is cheap and healthful.

Shopkeepers will sell small quantities of produce (like a couple of apples or some carrots), but it’s customary to let the merchant choose for you; watch locals and imitate. To get ripe fruit, say “per oggi” (pehr OH-jee; for today). Either say or indicate by gesturing how much you want. The word basta (BAH-stah; enough) works as a question or as a statement. Items can be sold by weight, or per slice (fetta), piece (pezzi), portion (porzione), or takeout container (contenitore). To avoid being overcharged, figure out the approximate cost, and do the arithmetic.

Even on a budget, picnics can be an adventure in high cuisine. Be daring. It’s fairly cheap to buy a bit of anything for the joy of sampling regional specialties.

Gelato

Most gelaterie clearly display prices and sizes. Even if you order the smallest size cup or cone, you can generally pick out two flavors. A key to gelato appreciation is sampling liberally. Ask, as Italians do, for a taste: “Un assaggio, per favore?”

In the textbook gelateria scam (which is fortunately rare), the tourist orders gelato and the clerk selects a fancy, expensive chocolate-coated waffle cone, piles it high with huge scoops, and cheerfully charges the tourist €10. To avoid rip-offs, point to the price or say what you want—for instance, a €3 cup: “Una coppetta da tre euro” (OO-nah koh-PEH-tah dah tray eh-OO-roh).

The best gelaterie display signs reading artiginale, nostra produzione, or produzione propia, indicating the gelato is made on the premises. Seasonal flavors are also a good sign, as are mellow hues (avoid colors that don’t appear in nature). Gelato stored in covered metal tins (rather than white plastic) is more likely to be homemade. Gourmet gelato shops (such as Grom) are popping up all over Italy, selling exotic flavors.

Gelato variations or alternatives include sorbetto (sorbet—made with fruit, but no milk or eggs); granita or grattachecca (a cup of slushy ice with flavored syrup); and cremolata (a gelato-granita float).

Beverages

Italian bars serve great drinks—hot, cold, sweet, caffeinated, or alcoholic.

Water, Juice, and Cold Drinks

Italians are notorious water snobs. At restaurants, your server just can’t understand why you wouldn’t want good water to go with your good food. It’s customary and never expensive to order a litro or mezzo litro (half-liter) of bottled water. Acqua leggermente effervescente (lightly carbonated water) is a meal-time favorite. Or simply ask for con gas if you want fizzy water and senza gas if you prefer still water. You can ask for acqua del rubinetto (tap water) in restaurants, but your server may give you a funny look.

Chilled bottled water—still (naturale) or carbonated (frizzante)—is sold cheap in stores. Half-liter mineral-water bottles are available everywhere for about €1 (I refill my water bottle with tap water).

Juice is succo, and spremuta means freshly squeezed. Order una spremuta (don’t confuse it with spumante, sparkling wine). In grocery stores, you can get a liter of O.J. for the price of a Coke or coffee. Look for 100% succo or senza zucchero (without sugar) on the label—or be surprised by something diluted and sugary sweet. To save money, buy juice in cheap liter boxes, drink some, and pour (and store) the excess in an empty water bottle.

Tè freddo (iced tea) is usually from a can—sweetened and flavored with lemon or peach. Lemonade is limonata.

Coffee and Other Hot Drinks

Espresso was born in Italy. If you ask for “un caffè,” you’ll get a shot of espresso in a little cup—the closest thing to American-style drip coffee is a caffè americano. Most Italian coffee drinks begin with espresso, to which they add varying amounts of hot water and/or steamed or foamed milk. Milky drinks, like cappuccino or caffè latte, are served to locals before noon and to tourists any time of day (to an Italian, cappuccino is a morning drink; they believe having milk after a big meal or anything with tomato sauce impairs digestion). If they add any milk after lunch, it’s just a tiny bit, in a caffè macchiato. Italians like their coffee only warm—to get it very hot, request “Molto caldo, per favore” (MOHL-toh KAHL-doh pehr fah-VOH-ray). Any coffee drink is available decaffeinated—ask for it decaffeinato (deh-kah-feh-NAH-toh). Cioccolato is hot chocolate. Tè is hot tea.

Ordering Wine

To order a glass of red or white wine, say, “Un bicchiere di vino rosso / bianco.” House wine comes in a carafe; choose from a quarter-liter pitcher (8.5 oz, un quarto), half-liter pitcher (17 oz, un mezzo), or one-liter pitcher (34 oz, un litro). Salute!

|

English |

Italian |

|

wine |

vino (VEE-noh) |

|

house wine |

vino della casa (VEE-noh DEH-lah KAH-zah) |

|

glass |

bicchiere (bee-kee-EH-ree) |

|

bottle |

bottiglia (boh-TEEL-yah) |

|

carafe |

caraffa (kah-RAH-fah) |

|

red |

rosso (ROH-soh) |

|

white |

bianco (bee-AHN-koh) |

|

rosé |

rosato (roh-ZAH-toh) |

|

sparkling |

spumante / frizzante (spoo-MAHN-tay / freed-ZAHN-tay) |

|

dry |

secco (SEH-koh) |

|

earthy |

terroso (teh-ROH-zoh) |

|

fruity |

fruttato (froo-TAH-toh) |

|

full-bodied |

corposo / pieno (kor-POH-zoh / pee-EH-noh) |

|

mature |

maturo (mah-TOO-roh) |

|

sweet |

dolce (DOHL-chay) |

Experiment with a few of the options:

Cappuccino: Espresso with foamed milk on top (cappuccino freddo is iced cappuccino).

Caffè latte: Espresso mixed with hot milk, no foam, in a tall glass (if you order just a “latte,” you’ll get only warm milk).

Caffè macchiato: Espresso “marked” with a splash of milk, in a small cup.

Latte macchiato: Layers of hot milk and foam, “marked” by an espresso shot, in a tall glass (if you order simply a “macchiato,” you’ll probably get a caffè macchiato).

Caffè lungo: Concentrated espresso diluted with a tiny bit of hot water, in a small cup.

Caffè americano: Espresso diluted with even more hot water, in a larger cup.

Caffè corretto: Espresso “corrected” with a shot of liqueur (normally grappa, amaro, or sambuca).

Marocchino: “Moroccan” coffee with espresso, foamed milk, and cocoa powder; the similar mocaccino has chocolate instead of cocoa.

Caffè freddo: Sweet and iced espresso.

Caffè hag: Instant decaf.

Alcoholic Beverages

Beer: While Italy is traditionally considered wine country, in recent years there’s been a huge and passionate growth in the production of craft beer (birra artigianale). Even in small towns, you’ll see microbreweries slinging their own brews. You’ll also find local brews (Peroni and Moretti), as well as imports such as Heineken. Beer on tap is alla spina. Get it piccola (33 cl, 11 oz), media (50 cl, about a pint), or grande (a liter). Italians drink mainly lager beers. A lattina (lah-TEE-nah) is a can and a bottiglia (boh-TEEL-yah) is a bottle.

Cocktails and Spirits: Italians appreciate both aperitivi (palate-stimulating cocktails) and digestivi (after-dinner drinks designed to aid digestion). Popular aperitivo options include Campari (dark-colored bitters with herbs and orange peel), Americano (vermouth with bitters, brandy, and lemon peel), and Punt e Mes (sweet red vermouth and red wine).

Digestivo choices are usually either a strong herbal bitters (such as amaro—popular commercial brands are Fernet Branca and Montenegro) or something sweet, like any of these liqueurs: amaretto (almond-flavored), Frangelico (hazelnut), limoncello (lemon), and nocino (walnut). Grappa is a strong brandy; stravecchio is an aged, mellower variation.

Wine: Wine (vino) is part of the Italian culinary trinity—grape, olive, and wheat. (I’d add gelato.) Ideal conditions for grapes (warm climate, well-draining soil, and an abundance of hillsides) make the Italian peninsula a paradise for grape growers, winemakers, and wine drinkers. Italy makes and consumes more wine per capita than any other country.

In general, Italy designates its wines by one of four official categories (check the label):

Vino da Tavola (VDT) is table wine, the lowest grade, made from grapes grown anywhere in Italy. It’s inexpensive and quite good. Restaurants are often proud of their vino della casa (house wine).

Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC), which meets national standards for high-quality wine, is made from grapes grown in a defined area; it’s usually affordable and surprisingly good.

Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Guarantita (DOCG) is the highest grade; it’s just like DOC, though its quality is guaranteed. Riserva indicates a DOC or DOCG wine matured for a longer time.

Indicazione Geographica Tipica (IGT) is a broad group of wines that range from basic to some of the best. They’re not limited to Italian grapes, but give vintners creative license. This category includes the Super Tuscans—wines made from a mix of international grapes.

STAYING CONNECTED

Staying connected in Europe gets easier and cheaper every year. The simplest solution is to bring your own device—mobile phone, tablet, or laptop—and use it just as you would at home (following the tips below, such as connecting to free Wi-Fi whenever possible). Another option is to buy a European SIM card for your mobile phone—either your US phone or one you buy in Europe. Or you can travel without a mobile device and use European landlines and computers to connect. Each of these options is described below, and you’ll find even more details at www.ricksteves.com/phoning.

Using Your Mobile Device in Europe

Roaming with your mobile device in Europe doesn’t have to be expensive. These budget tips and options will keep your costs in check.

Use free Wi-Fi whenever possible. You can access the Internet, send texts, and even make voice calls over Wi-Fi. It’s smart to save most of your online tasks for Wi-Fi unless you have an unlimited-data plan.

Most accommodations in Europe offer free Wi-Fi (pronounced wee-fee in Italian). Many cafés—including Starbucks and McDonald’s—have hotspots for customers; look for signs offering it and ask for their Wi-Fi password when you buy something. You’ll also often find Wi-Fi at TIs, city squares, major museums, public-transit hubs, airports, and aboard trains and buses.

Sign up for an international plan for your mobile phone. Most providers offer a global calling plan that cuts the per-minute cost of phone calls and texts, and a flat-fee data plan that includes a certain amount of megabytes. Your normal plan may already include international coverage (T-Mobile’s does).

Before your trip, call your provider or check online to confirm that your phone will work in Europe, and research your provider’s international rates. A day or two before you leave, activate the plan by calling your provider or logging on to your mobile phone account. Remember to cancel your plan (if necessary) when your trip’s over.

Minimize the use of your cellular network. When you can’t find Wi-Fi, you can use your cellular network—convenient but slower and potentially expensive—to connect to the Internet, text, or make voice calls. When you’re done, avoid further charges by manually switching off “data roaming” or “cellular data” (in your device’s Settings menu; if you don’t know how to switch it off, ask your service provider or Google it). Another way to make sure you’re not accidentally using data roaming is to put your device in “airplane” or “flight” mode (which also disables phone calls and texts, as well as data), and then turn on Wi-Fi as needed.

Don’t use your cellular network for bandwidth-gobbling tasks, such as Skyping, downloading apps, and watching YouTube—save these for when you’re on Wi-Fi. Using a navigation app such as Google Maps can take lots of data, so use this sparingly.

Limit automatic updates. By default, your device is constantly checking for a data connection and updating apps. It’s smart to disable these features (in your device’s Setting menu) so they’ll only update when you’re on Wi-Fi, and to change your device’s email settings from “auto-retrieve” to “manual” (or from “push” to “fetch”).

It’s also a good idea to keep track of your data usage. On your device’s menu, look for “cellular data usage” or “mobile data” and reset the counter at the start of your trip.

Tips on Internet Security

Using the Internet while traveling brings added security risks, whether you’re getting online with your own device or at a public terminal using a shared network.

First, make sure that your device is running the latest version of its operating system and security software. Next, ensure that your device is password- or passcode-protected so thieves can’t access your information if your device is stolen. For extra security, set passwords on apps that access key info (such as email or Facebook).

On the road, use only legitimate Wi-Fi hotspots. Ask the hotel or café staff for the specific name of their Wi-Fi network, and make sure you log on to that exact one. Hackers sometimes create a bogus hotspot with a similar or vague name (such as “Hotel Europa Free Wi-Fi”). The best Wi-Fi networks require entering a password.

Be especially cautious when checking your online banking, credit-card statements, or other personal-finance accounts. Internet security experts advise against accessing these sites while traveling. Even if you’re using your own mobile device at a password-protected hotspot, any hacker who’s logged on to the same network may be able see what you’re doing. If you do need to log on to a banking website, use a hard-wired connection (such as an Ethernet cable in your hotel room) or a cellular network, which is safer than Wi-Fi.

Never share your credit-card number (or any other sensitive information) online unless you know that the site is secure. A secure site displays a little padlock icon, and the URL begins with https (instead of the usual http).

Use Skype or other calling/messaging apps for cheaper calls and texts. Certain apps let you make voice or video calls or send texts over the Internet for free or cheap. If you’re bringing a tablet or laptop, you can also use them for voice calls and texts. All you have to do is log on to a Wi-Fi network, then contact any of your friends or family members who are also online and signed in to the same service. You can make voice and video calls using Skype, Viber, FaceTime, and Google+ Hangouts. If the connection is bad, try making an audio-only call.

You can also make voice calls from your device to telephones worldwide for just a few cents per minute using Skype, Viber, or Hangouts if you pre-buy credit.

To text for free over Wi-Fi, try apps like Google+ Hangouts, What’s App, Viber, and Facebook Messenger. Apple’s iMessage connects with other Apple users, but make sure you’re on Wi-Fi to avoid data charges.

Using a European SIM Card

This option works well for those who want to make a lot of voice calls at cheap local rates. Either buy a phone in Europe (as little as $40 from mobile-phone shops anywhere), or bring an “unlocked” US phone (check with your carrier about unlocking it). With an unlocked phone, you can replace the original SIM card (the microchip that stores info about the phone) with one that will work with a European provider.

Phoning Cheat Sheet

Here are instructions for dialing, along with examples of how to call one of my recommended hotels in Florence (tel. 055-289-592).

Calling from the US to Europe: Dial 011 (US access code), country code (39 for Italy), and phone number.* To call my recommended hotel in Florence, I dial 011-39-055-213-154.

Calling from Europe to the US: Dial 00 (Europe access code), country code (1 for US), area code, and phone number. To call my office in Edmonds, Washington, I dial 00-1-425-771-8303.

Calling country to country within Europe: Dial 00, country code, and phone number.* To call the Florence hotel from Germany, I dial 00-39-055-213-154.

Calling within Italy: Dial the entire phone number. To call the Florence hotel from Rome, I dial 055-213-154 (Italy doesn’t use area codes).

Calling with a mobile phone: The “+” sign on your mobile phone automatically selects the access code you need (for a “+” sign, press and hold “0”).* To call the Florence hotel from the US or Europe, I dial +39-055-213-154.

For more dialing help, see www.howtocallabroad.com.

*If the phone number starts with zero, keep it if calling Italy, but drop it when calling other countries.

|

Country |

Code |

|

Austria |

43 |

|

Belgium |

32 |

|

Czech Republic |

420 |

|

Denmark |

45 |

|

England |

44 |

|

France |

33 |

|

Germany |

49 |

|

Greece |

30 |

|

Hungary |

36 |

|

Ireland/N Ireland |

353/44 |

|

Italy |

39 |

|

Netherlands |

31 |

|

Norway |

47 |

|

Portugal |

351 |

|

Scotland |

44 |

|

Spain |

34 |

|

Switzerland |

41 |

In Europe, buy a European SIM card. Inserted into your phone, this card gives you a European phone number—and European rates. SIM cards are sold at mobile-phone shops, department-store electronics counters, some newsstands, and even vending machines. Costing about $5-10, they usually include about that much prepaid calling credit, with no contract and no commitment. You can still use your phone’s Wi-Fi function to get online. To get a SIM card that also includes data costs (including roaming), figure on paying $15-30 for one month of data within the country you bought it. This can be cheaper than data roaming through your home provider. To get the best rates, buy a new SIM card whenever you arrive in a new country.

I like to buy SIM cards at a mobile-phone shop where there’s a clerk to help explain the options and brands. In Italy, the major mobile phone providers are Wind, TIM, Vodafone, and 3 (“Tre”). Certain SIM-card brands—including Lebara and Lycamobile, both of which operate in multiple European countries—are reliable and economical. Ask the clerk to help you insert your SIM card and set it up, and to show you how to use it. In some countries—including Italy—you’ll be required to register the SIM card with your passport as an antiterrorism measure (which may mean you can’t use the phone for the first hour or two).

When you run out of credit, you can top it up at newsstands, tobacco shops, mobile-phone stores, or many other businesses (look for your SIM card’s logo in the window), or online.

Using Landlines and Computers in Europe

It’s easy to travel in Europe without a mobile device. You can check email or browse websites using public computers and Internet cafés, and make calls from your hotel room and/or public phones. For free directory assistance in English, call 170.

Phones in your hotel room can be inexpensive for local calls and calls made with cheap international phone cards (carta telefonica prepagata internazionale, KAR-tah teh-leh-FOHN-ee-kah pray-pah-GAH-tah in-ter-naht-zee-oh-NAH-lay—sold at many post offices, newsstands, street kiosks, tobacco shops, and train stations). You’ll either get a prepaid card with a toll-free number and a scratch-to-reveal PIN code, or a code printed on a receipt; to make a call, dial the toll-free number, follow the prompts, enter the code, then dial your number.

Most hotels charge a fee for placing local and “toll-free” calls, as well as long-distance or international calls—ask for the rates before you dial. Since you’re never charged for receiving calls, it’s better to have someone from the US call you in your room.

You’ll see public pay phones in post offices and train stations. The phones generally come with multilingual instructions, and most work with insertable Telecom Italia phone cards (sold at post offices, newsstands, etc.). To use the card, rip off the perforated corner to “activate” it, take the phone off the hook, insert the card, wait for a dial tone, and dial away. With the exception of Great Britain, each European country has its own insertable phone card—so your Italian card won’t work in a French phone.

It’s always possible to find public computers: at your hotel (many have one in their lobby for guests to use), or at an Internet café or library (ask your hotelier or the TI for the nearest location). If typing on a European keyboard, use the “Alt Gr” key to the right of the space bar to insert the extra symbol that appears on some keys. Italian keyboards are a little different from ours; to type an @ symbol, press the “Alt Gr” key and the key that shows the @ symbol. If you can’t locate a special character, simply copy it from a Web page and paste it into your email message.

You can mail one package per day to yourself worth up to $200 duty-free from Europe to the US (mark it “personal purchases”). If you’re sending a gift to someone, mark it “unsolicited gift.” For details, visit www.cbp.gov and search for “Know Before You Go.”

The Italian postal service works fine, but for quick transatlantic delivery (in either direction), consider services such as DHL (www.dhl.com).

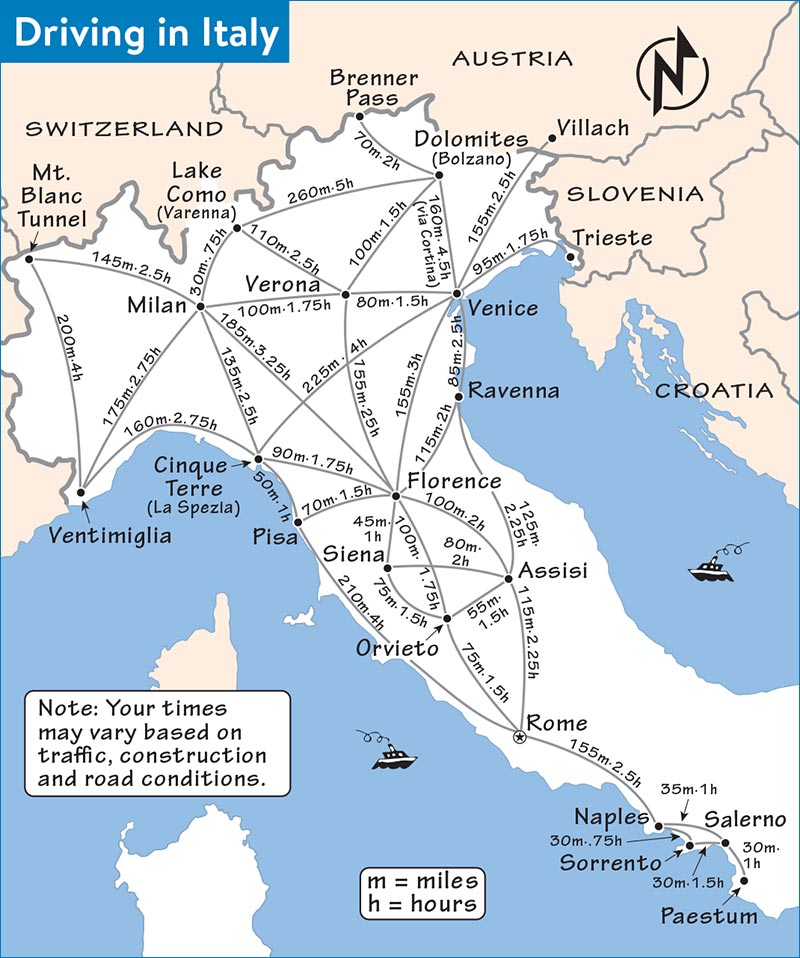

TRANSPORTATION

Considering the convenience and affordability of Italy’s trains and buses, I’d do most of Italy by public transportation. A car is a worthless, expensive headache in big cities and along the Cinque Terre. If you want to drive, consider taking the train between the big, intense cities (Rome, Naples area, Florence, and Venice), and renting a car for exploring the hill-town region. My recommended hill towns can be done by train and/or bus, but if you have time to putter through the countryside, stopping here and there for photo ops and wineries, a car is a good way to go.

For covering long distances in Europe, look into flying.

Trains

Train tickets are a good value in Italy. To travel economically, you can simply buy tickets as you go. Taking fast trains costs more than slow trains, but all are cheaper per mile than their northern European counterparts.

Fares are shown on the map on here, though fares can vary for the same journey, mainly depending on the time of day, the speed of the train, and advance discounts. First-class tickets cost up to 50 percent more than second-class.

In general, if you’re on a tight budget, compare the different options (see “Types of Trains” next) before buying. Assume you’ll need to make reservations for fast trains.

Types of Trains

Most trains in Italy are operated by the state-run Trenitalia company (a.k.a. Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane, abbreviated FS or FSI, www.trenitalia.com).

Since ticket prices depend on the speed of the train, it helps to know the different types of trains: The fastest trains are the Frecce trains: Frecciabianca, Frecciargento, and so on. Frecce trains may be marked on schedules as ES, AV, or EAV. Other fast trains (though not as fast as Frecce) are IC (InterCity) and EC (EuroCity). Medium-speed trains are RV (regionale veloce), IR (InterRegio), D (diretto), and E (espresso). Pokey trains are R or REG (regionali).

If you’re traveling with a rail pass, note that reservations are required for EC and international trains (€5) and Frecce trains (€10). Reservations are optional for rail-pass holders on IC trains, and you can’t make reservations for regional trains, such as most Pisa-Cinque Terre connections.

A private train company called Italo runs fast trains on these two major routes: Venice-Padua-Bologna-Florence-Rome and Turin-Milan-Bologna-Florence-Rome-Naples. They charge about the same rates as Trenitalia, and they also offer discounts for advance purchase. In some cities, such as Milan, their trains use secondary stations—if taking an Italo train, pay attention to which station you need. Italo does not accept rail passes, but they’re a worthy alternative for point-to-point tickets.

Schedules

At the station, large printed schedules are posted (departure—partenzi—posters are always yellow; the white posters show arrivals); these list both Trenitalia and Italo routes when applicable.

You can also check schedules at ticket machines (marked Trenitalia or Italo—each company maintains their own machines). Enter the desired date, time, and destination to see your options.

Online, you can visit www.trenitalia.it and www.italotreno.it (domestic journeys only); for international trips, use www.bahn.com (Germany’s excellent all-Europe schedule website). Trenitalia offers a single all-Italy telephone number for train information (24 hours daily, toll tel. 892-021, in Italian only, consider having your hotelier call for you); for Italo trains, call 06-0708.

Deciphering Italian Train Schedules

At the station, look for the big yellow posters labeled Partenze—Departures (ignore the white posters, which show arrivals). In stations with Italo service, the posted schedules also include the FS or Italo logos.

Schedules are listed chronologically, hour by hour, showing the trains leaving the station throughout the day. Each schedule has columns:

✵ The first column (Ora) lists the time of departure.

✵ The next column (Treno) shows the type of train.

✵ The third column (Classi Servizi) lists the services available (first- and second-class cars, dining car, cuccetta berths, etc.) and, more importantly, whether you need reservations (usually denoted by an R in a box). All Frecce trains, many EuroCity (EC) trains, and most international trains require reservations.

✵ The next column lists the destination of the train (Principali Fermate Destinazioni), often showing intermediate stops, followed by the final destination, with arrival times listed throughout in parentheses. Note that your final destination may be listed in fine print as an intermediate destination. For example, if you’re going from Milan to Florence, scan the schedule and you’ll notice that virtually all trains that terminate in Rome stop in Florence en route. Travelers who read the fine print end up with a far greater choice of trains.

✵ The next column (Servizi Diretti e Annotazioni) has pertinent notes about the train, such as “also stops in...” (ferma anche a...), “doesn’t stop in...” (non ferma a...), “stops in every station” (ferma in tutte le stazioni), “delayed...” (ritardo...), and so on.

✵ The last column lists the track (Binario) the train departs from. Confirm the binario with an additional source: a ticket seller, the electronic board that lists immediate departures, monitors on the platform, or the railway officials who are usually standing by the train unless you really need them.

For any odd symbols on the poster, look at the key at the end. Some of the phrasing can be deciphered easily, such as servizio periodico (periodic service—doesn’t always run). For the trickier ones, ask a local or railway official, or simply take a different train.

Remember that you can also check schedules—for trains anywhere in Italy, not just from the station you’re currently in—at the station’s ticket machines.

Be aware that Trenitalia and Italo don’t cooperate. If you buy a ticket for one train line, it’s not valid on the other. Even if you’re just looking for schedule information, the company you ask will most likely ignore the other’s options.

Newsstands sell up-to-date regional and all-Italy timetables (€5 for the orario ferroviaro).

Buying Train Tickets

You have several options for buying train tickets: at the station (easy at machines for domestic trips), a travel agency (a good choice for booking international trips), or online (ideal for getting advance-purchase discounts). Because most Italian trains run frequently, you can keep your travel plans flexible by purchasing tickets as you go. You can buy tickets for several trips at one station when you are ready to commit.

Train Costs in Italy

Map key: Approximate point-to-point one-way second-class rail fares in US dollars. First class costs 50 percent more.

Before deciding to get a rail pass, add up the approximate ticket costs for your itinerary. If you’ll be making short, inexpensive trips each day, you’ll probably find it’s cheaper to buy tickets as you go in Italy.

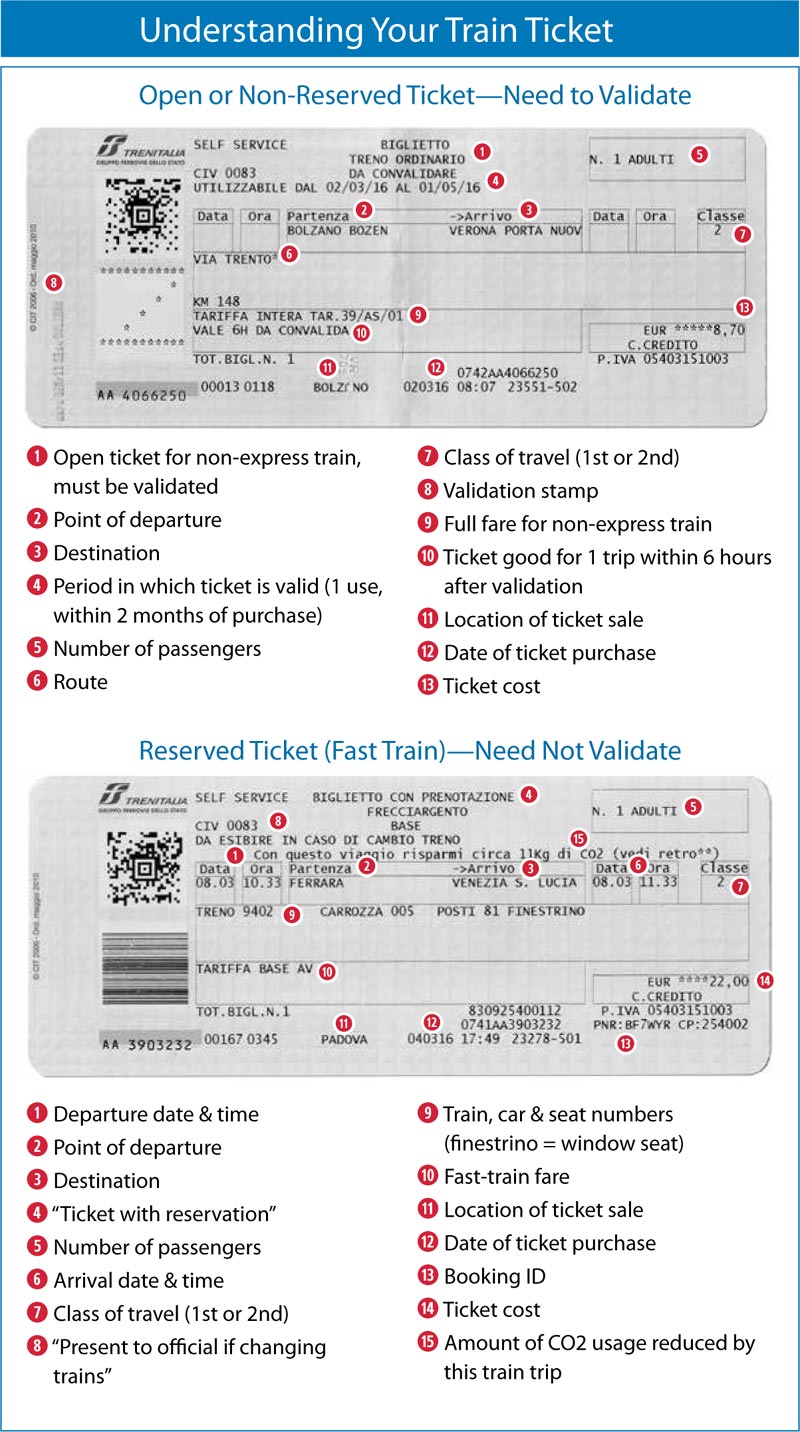

At the Station: Ticket machines in stations are user-friendly, so you can often avoid long lines at ticket windows. You’ll be able to purchase tickets for travel within Italy (not international trains), make seat reservations, and even book a cuccetta (koo-CHEH-tah; overnight berth). Pay all ticket costs in the station before you board, or you’ll pay a penalty on the train.

Trenitalia’s ticket machines (either green-and-white or red) are found in all but the tiniest stations in Italy. You can pay by cash (they give change) or by debit or credit card (even for small amounts, but you may need to enter your PIN). Select English, then your destination. If you don’t immediately see the city you’re traveling to, keep keying in the spelling until it’s listed. You can choose from first- and second-class seats, request tickets for more than one traveler, and (on the high-speed Frecce trains) choose an aisle or window seat. Don’t select a discount rate without being sure that you meet the criteria (for example, Americans are not eligible for certain EU or resident discounts). Rail-pass holders can use the machines to make seat reservations. If you need to validate your ticket, you can do it in the same machine if you’re boarding your train right away.

To buy tickets for Italo trains, look for a dedicated service counter (in most major rail stations), or a red ticket machine labeled Italo.

To buy international tickets, or anything else that requires a real person, you must go to a ticket window. Be sure you’re in the correct line. Key terms are: biglietti (general tickets), prenotazioni (reservations), nazionali (domestic), and internazionali.

Travel Agencies: Local travel agencies sell domestic and international tickets and make reservations. They charge a small fee, but the language barrier (and the lines) can be smaller than at the station’s ticket windows.

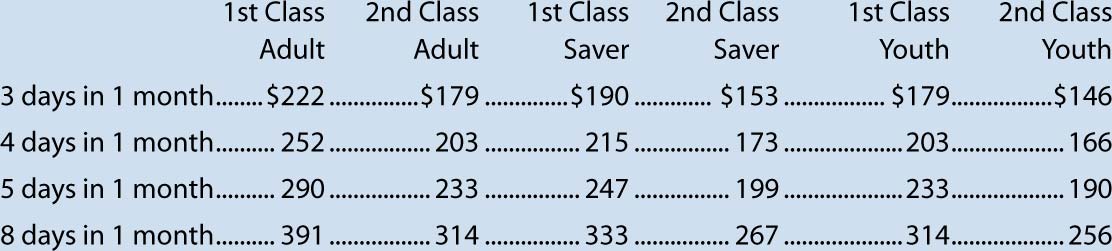

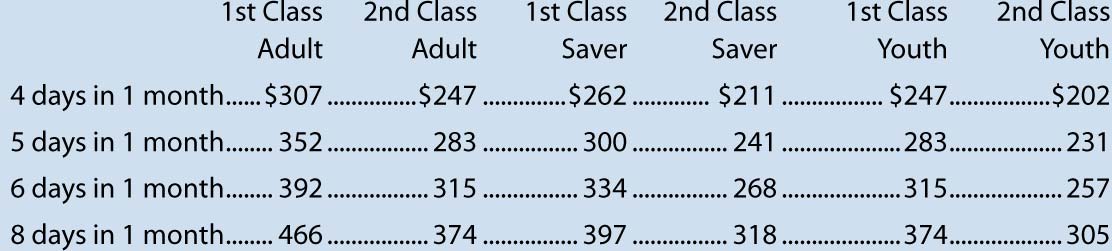

Rail Passes

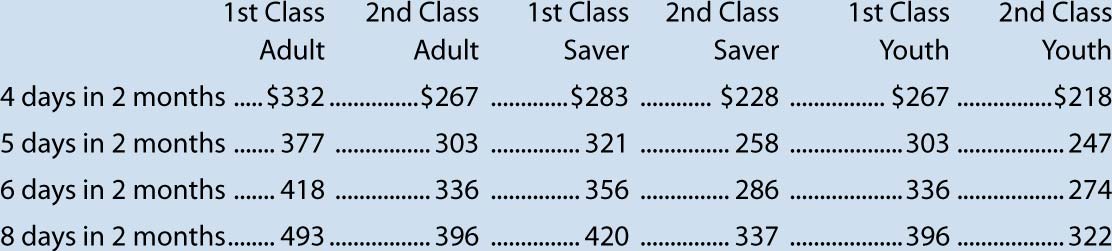

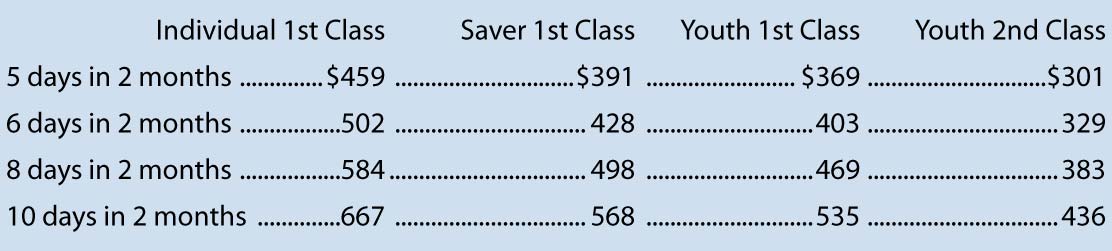

Prices listed are subject to change. For the latest prices, details, and train schedules (and easy online ordering), see www.ricksteves.com/rail.

“Saver” prices are per person for two or more people traveling together. “Youth” means under age 26. Up to two kids age 4-11 travel free with each adult on any Eurail-brand pass. Additional kids pay the youth rate. Kids under age 4 travel free.

ITALY PASS

GREECE-ITALY PASS

Covers deck passage on overnight Superfast Ferries between Patras, Greece and Bari or Ancona, Italy (starts use of one travel day). Does not cover travel to or on Greek islands. Very few trains run in Greece.

SPAIN-FRANCE PASS or SPAIN-ITALY PASS

Spain-Italy pass does not cover travel through France. Paris-Italy night trains do not accept rail passes.

SELECTPASS

This pass covers travel in four adjacent countries.

Online or Phone: For travelers ready to lock in dates and times weeks or months in advance, buying nonrefundable tickets online can cut costs in half, particularly for long-haul trips. It also makes sense to reserve ahead for busy weekend or holiday travel. For Trenitalia, see www.trenitalia.com. You can book Italo tickets online (www.italotreno.it) or by phone (tel. 06-0708). For travel starting in another country, buy the ticket from the starting country’s website.