Football For Dummies (2015)

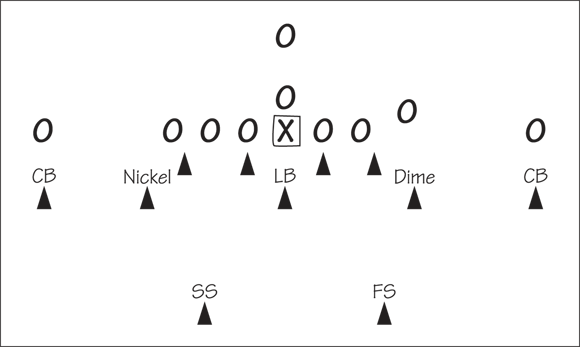

Part III

The Big D

Visit www.dummies.com/extras/football for an article on one of the great teams of all time, the 1946-1955 Cleveland Browns.

Visit www.dummies.com/extras/football for an article on one of the great teams of all time, the 1946-1955 Cleveland Browns.

In this part …

· Take a look at the defensive line and understand sacks and tackles

· Look at how the secondary — the last line of defense — operates

· Brush up on defensive tactics and how to handle difficult situations on the field

Chapter 9

These Guys Are Huge: The Defensive Line

In This Chapter

![]() Looking at the different types of defensive linemen, from noses to ends

Looking at the different types of defensive linemen, from noses to ends

![]() Getting the lowdown on linebackers

Getting the lowdown on linebackers

![]() Understanding how the defense lines up

Understanding how the defense lines up

![]() Finding out about sacks, tackles, and more

Finding out about sacks, tackles, and more

The game of football has changed a lot since I entered the NFL in 1981. Today’s defensive linemen are bigger, and maybe faster, than those who played 30 years ago. Of course, they’ve had to keep pace with their main opposition, the offensive linemen. When I played in the NFL, you could count the number of 300-pound offensive linemen on one hand. Now, you need more than two hands to count a single team’s 300-pounders!

Defensive linemen have to battle these huge offensive linemen. Then they have to deal with running backs and quarterbacks, whose main function in life is to make the defensive line look silly. Few linemen can run and move, stop and go, like running back LeSean McCoy of the Buffalo Bills and quarterback Russell Wilson of the Seattle Seahawks. These guys are two of the best offensive players in the NFL, and they’re also superb all-around athletes. Linemen, who generally weigh 100 pounds more than McCoy or Wilson, have a difficult time catching and tackling players like them. The few who can are the great linemen. However, many linemen have the ability to put themselves in position to stop a great offensive player. The key is: Can they make the tackle?

In this chapter, I address the responsibilities of every defensive lineman and talk about all the linebacker positions, explaining how those two segments of the defense interact.

Those Big Guys Called Linemen

Defensive linemen are big players who position themselves on the line of scrimmage, across from the offensive linemen, prior to the snap of the ball. Their job is to stop the run, or in the case of a pass play, sack the quarterback, as shown in Figure 9-1 .

Photo credit: © Bernie Nunez/Getty Images

Figure 9-1: Nose tackle Vince Wilfork sacks the quarterback — again.

The play of the defensive linemen (as a group) can decide the outcome of many games. If they can stop the run without much help from the linebackers and defensive backs, they allow those seven defensive players to concentrate on pass defense (and their coverage responsibilities). Ditto if they can sustain a constant pass-rush on the quarterback without help from a blitzing defensive back or linebacker.

For the defense to do its job effectively, linemen and linebackers (the players who back up the defensive linemen) must work together. This collaboration is called scheming — devising plans and strategies to unmask and foil the offense and its plays. To succeed as a group, a defense needs linemen who are selfless — willing to go into the trenches and play the run while taking on two offensive linemen. These players must do so without worrying about not getting enough pass-rush and sack opportunities.

The following sections take an in-depth look at the defensive line, which is also known as the D line.

Looking closely at the D line

Defensive linemen usually start in a three-point stance (one hand and two feet on the ground). In rare situations, they align themselves in a four-point stance (both hands and both feet on the ground) to stop short-yardage runs. The latter stance is better because the lineman wants to gain leverage and get both of his shoulders under the offensive lineman and drive him up and backward. He needs to do anything he can to stop the offensive lineman’s forward charge.

Defensive linemen are typically a rare combination of size, speed, and athleticism, and, in terms of weight, they’re the largest players on the defense. A defensive lineman’s primary job is to stop the run at the line of scrimmage and to rush (chase down) the quarterback when a pass play develops.

Defensive linemen are typically a rare combination of size, speed, and athleticism, and, in terms of weight, they’re the largest players on the defense. A defensive lineman’s primary job is to stop the run at the line of scrimmage and to rush (chase down) the quarterback when a pass play develops.

Defensive linemen seldom receive enough credit for a job well done. In fact, at times, a defensive lineman can play a great game but go unnoticed by the fans and the media, who focus more on offensive players, like quarterbacks and wide receivers, and defensive playmakers, such as defensive backs and linebackers. Defensive linemen are noticed in some situations, though, like when they

· Record a sack (tackle a quarterback for a loss while he’s attempting to pass)

· Make a tackle for a loss or for no gain

Often, defensive linemen contain an opponent (neutralize him, forcing a stalemate) or deal with a double-team block (two offensive linemen against one defensive lineman) in order to free up one of their teammates to make a tackle or sack. The defensive lineman position can be a thankless one because few players succeed against double-team blocks. The only place where one guy beats two on a regular basis is in the movies.

Identifying types of defensive linemen

The term defensive lineman doesn’t refer to a specific position, as you might think. A player who plays any of the following positions is considered a defensive lineman:

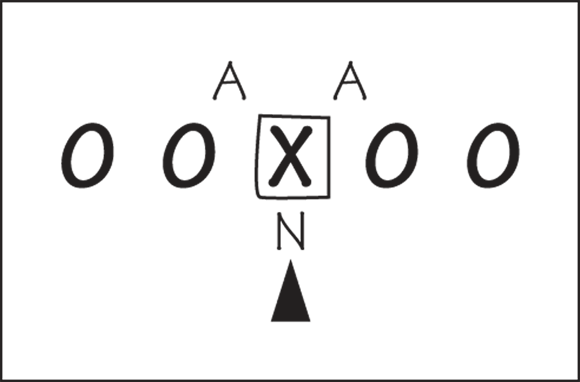

· Nose tackle: The defensive lineman who lines up directly across from the center, “nose to nose,” as shown in Figure 9-2 . Like in baseball, you build the strength of your team up the middle, and without a good nose tackle, your defense can’t function. This player needs to be prepared for a long day because his job is all grunt work, with little or no chance of making sacks or tackles for minus yardage.

The nose tackle knows he’ll be double-blocked much of the game. He’s responsible for gaps on each side of the center (known as the A gaps). Prior to the snap, the nose tackle looks at the ball. When the center snaps the ball, the nose tackle attacks the center with his hands. Because the nose tackle is watching the ball, the center can sucker him into moving early by suddenly flinching his arms and simulating a snap.

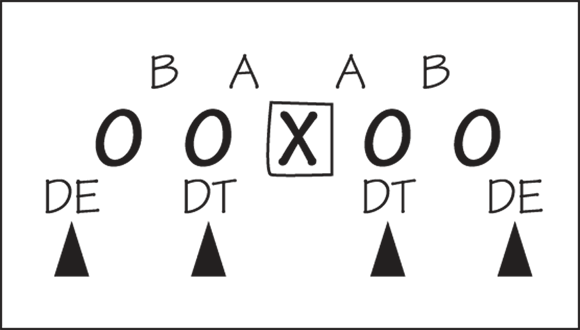

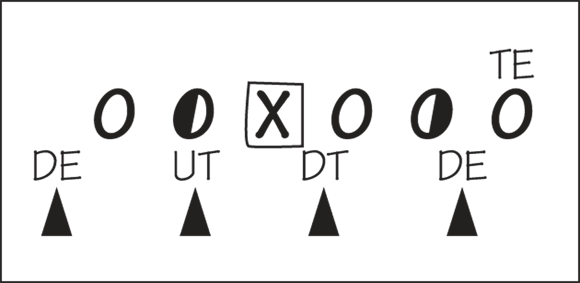

· Defensive tackles: The two players who line up inside the defensive ends and usually opposite the offensive guards. The defensive tackles’ responsibilities vary according to the defensive call or scheme; they can be responsible for the A gaps (the space between the center and guards) or the B gaps (the space between the guards and tackles), as shown in Figure 9-3 .

Defensive tackles do a great deal of stunting, or executing specific maneuvers that disrupt offensive blocking schemes. They also adjust their alignments to the inside or outside shoulders of the offensive guards based on where they anticipate the play is headed. Often, they shift to a particular position across from the offensive linemen when the game unfolds and they discover a particular weakness to an offensive lineman’s left or right side.

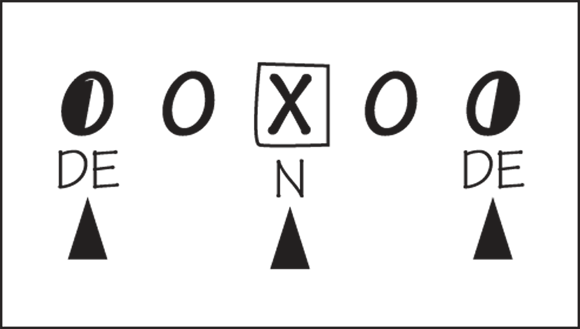

· Defensive ends: The two defensive linemen who line up opposite the offensive tackles or on those players’ outside shoulders. Where the defensive ends line up varies according to the defensive call or scheme. For example, in a 4-3 defense, the defensive ends align wide because they have two defensive tackles to the inside of them (refer to Figure 9-3). In a 3-4 defense, the defensive ends align tighter, or closer to the center of the line, because they have only a nose tackle between them, as shown in Figure 9-4 . To find out more about 3-4 or 4-3 defenses, turn to Chapter 11.

The defensive ends are responsible for chasing the quarterback out of the pocket and trying to sack him. These players are usually smaller than nose tackles and defensive tackles in weight (that is, if you consider 270 pounds small), and they’re generally the fastest of the defensive linemen. The left defensive end is usually a little stronger against the run, a better tackler, and maybe not as quick to rush the quarterback. He’s generally tougher for an offensive lineman to move off the line of scrimmage. The right defensive end (who’s usually on the blind side of the quarterback) is the better pass-rusher. On a few teams, these ends flip sides when facing a left-handed quarterback, making the left defensive end the better pass-rusher.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-2: The nose tackle (N) lines up opposite the center.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-3: The defensive tackles (DT) line up inside the defensive ends (DE).

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-4: The defensive ends (DE) in a 3-4 defense.

Understanding what makes a good defensive lineman

Great defensive linemen, like J. J. Watt of the Houston Texans, are very rare players. Their combination of size, speed, strength, and durability isn’t found in many players. A good defensive lineman has the majority of these qualities:

· Size: A defensive lineman needs to be 260 pounds or bigger.

· Durability: Defensive linemen must be able to withstand the punishment of being hit or blocked on every play. Because they play 16 or more games a season, with about 70 plays per game, defensive linemen are hit or blocked about 1,000 times a season.

· Quickness: Speed is relative, but quickness is vital. A lineman’s first two steps after the ball is snapped should be like those of a sprinter breaking from the starting blocks. Quickness enables a defensive lineman to react and get in the proper position before being blocked. I call this “quickness in a phone booth.” A defensive lineman may not be fast over 40 yards, but in that phone booth (5 yards in any direction), he’s a cat!

· Arm and hand strength: Linemen win most of their battles when they ward off and shed blockers. Brute strength helps, but the true skill comes from a player’s hands and arms. Keeping separation between yourself and those big offensive linemen is the key not only to survival but also to success. Using your hands and arms to maintain separation cuts down on neck injuries and enables you to throw an offensive lineman out of your way to make a tackle.

· Vision: Defensive linemen need to be able to see above and around the offensive linemen. They also need to use their heads as tools to ward off offensive linemen attempting to block them. A defensive lineman initially uses his head to absorb the impact and stop the momentum of his opponent. Then, using his hands, he forces separation. But before the ball is snapped and before impact, the opponents’ backfield formation usually tells him what direction the upcoming play is going in. Anticipating the direction of the play may lessen the impact that his head takes after the ball is snapped.

· Instincts: Defensive linemen need to know the situation, down, and distance to a first down or a score. And they must be able to know and read the stances of all the offensive linemen they may be playing against. In an effort to move those big bodies where they need to go a little more quickly, offensive linemen often cheat in their stances more than any position in all of football. By doing so, they telegraph their intentions. Defensive linemen must assess these signs prior to the snap in order to give themselves an edge.

For example, if an offensive lineman is leaning forward in his stance, the play is probably going to be a run. The offensive lineman’s weight is forward so that he can quickly shove his weight advantage into his opponent and clear the way for the ball carrier. If the offensive lineman is leaning backward in his stance (weight on his heels, buttocks lower to the ground, head up a bit more), the play is usually going to be a pass; or he may be preparing to pull (run to either side rather than straight forward).

Delving into D-line lingo

Every football team has its own vocabulary for referring to different positions. For example, some teams give male names to all the defenders who line up to the offense’s tight end side — they call these defenders Sam, Bart, Otto, and so on. The defenders who align on the open end side (away from the tight end) are occasionally — but not always — given female names like Liz, Terri, and Wanda.

Here are some of the most common terms that teams use to refer to defensive linemen and their alignments:

· Under tackle: A defensive tackle who lines up outside the offensive guard to the split end side, as shown in Figure 9-5 . The entire defensive line aligns under (or inside) the tight end to the split end side. Some of the NFL’s best players are positioned as the under tackle. They possess strength and exceptional quickness off the ball, but they aren’t powerful players.

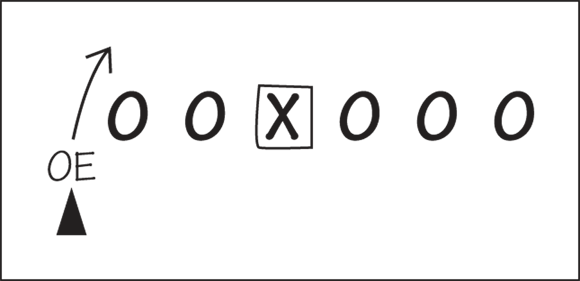

· Open end: A defensive end who lines up to the split end or open end side of the formation — away from the tight end side, as shown in Figure 9-6 . (If the offensive formation has two tight ends, there’s no open side and therefore no open end.) Coaches generally put their best pass-rusher at the open end position for two reasons: He has the athletic ability to match up with the offensive tackle, and if he’s positioned wide enough, a running back may be forced to attempt to block him, which would be a mismatch. Philadelphia Eagles end Trent Cole, who had 8 sacks in 2013, typifies the all-around open end.

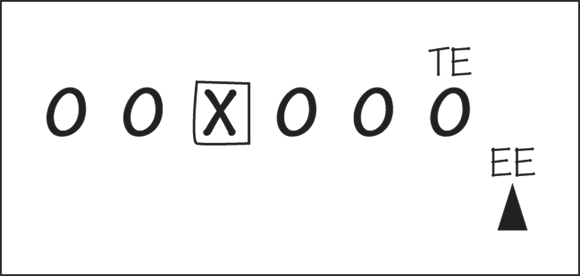

· Elephant end: The elephant end lines up on the tight end side of the offense, as shown in Figure 9-7 , and then attempts to disrupt the tight end’s release (his desire to escape the line of scrimmage and run down the field) on each play. This position was made famous by the San Francisco 49ers and was suited to the specific skills of Charles Haley, the only player to have earned five Super Bowl rings. Haley was ideal for the position because he was a great pass-rusher as well as strong, like an elephant, which enabled him to hold his position against the run. This position gives the defense an advantage because the tight end generally has trouble blocking this talented defensive end.

· Pass-rushing end: A player on the defense who has superior skills at combating offensive linemen and pressuring the quarterback. These ends can line up on either side of the defensive line. A pass-rushing end, like the Buffalo Bills’ Mario Williams, has the job of getting the best possible pass-rush, although he reacts to the run if a pass play doesn’t develop. If the quarterback is in a shotgun formation (see Chapter 5), the pass-rushing end must focus on where he expects the quarterback to be when he attempts to throw his pass.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-5: The under tackle (UT) lines up outside an offensive guard.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-6: The open end (OE) goes head-to-head with an offensive tackle or a running back.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-7: The elephant end (EE) is the tight end’s greatest foe.

Unlocking the keys to a defensive lineman

A key is what a defensive player looks at prior to the snap of the ball. For example, if it’s first-and-5, odds are that the offense will attempt to run the ball. The defensive lineman must key (watch) the offensive lineman and be prepared to react to his movements.

Here’s a quick rundown of a defensive lineman’s thought process prior to any play:

· Alignment: The defensive lineman has to make sure he’s aligned correctly.

· Stance: The stance he’s using should be to his advantage.

· Assignment: Does he know exactly what to do?

· Key: The lineman considers what/whom he should be looking at.

· Get off: He has to be quick off the football.

· Attack: The lineman thinks about attacking and controlling the offensive lineman with his hands, and then escaping by using his arms and shoulder to push by him.

· Execute: The lineman wants to execute his stunt to a specific area or gap and then react to where the ball is.

· Pursue: He always follows the football.

· Tackle: Finally, he can make the tackle.

And you thought tackling was the only chore of a defensive lineman! Now you know that they have many responsibilities (some of them thankless tasks), and they really have to be thinking to put themselves in a position to make a tackle.

Linebackers: The Leaders of the Defense

By the design of the defense, linebackers are the leaders of that 11-man squad. They’re the defensive quarterbacks and coaches on the field, beginning every play by giving the defensive call. They set the standard for every defense by being able to get to the ball before anyone else. They’re usually emotional leaders who excel in leading by example. If they play hard, their winning attitude carries over to the rest of the defense.

Although a linebacker’s main intention is to tackle the offensive player with the ball, the term linebacker has become one of the most complicated terms in football. Linebackers have become football hybrids due to their wide variety of responsibilities and enormous talent.

Football is in an age of specialization, and linebackers are used a great deal because they’re superior athletes who can learn a variety of skills and techniques. Some of them are suited to combat specific pass or run plays that the coaches believe the opposing offense plans to use. For that reason, coaches make defensive adjustments mainly by putting their linebackers in unusual alignments, making it difficult for the opposing quarterback and offensive players to keep track of the linebackers. Sometimes in a game, three linebackers leave the field and are replaced by two defensive backs and one linebacker who excels in pass defense. The roles are constantly changing as defenses attempt to cope with the varied abilities of a team’s offense.

Because linebackers play so many different roles, they come in all sizes, from 215 pounds to 270 pounds. Some are extremely fast and capable of sticking with a running back. Others are very stout and strong and are known for clogging the middle of a team’s offensive plans. Still others are tall and quick and extremely good pass-rushers. Regardless of skill or size differences, all linebackers have a few key characteristics in common: They have good instincts, are smart on their feet, can react immediately when the offense snaps the ball, and dominate each individual opponent they face.

The following sections offer insight into just what it is linebackers do, how they get those jobs done, and what kinds of linebackers you may see.

Figuring out what linebackers do

The job description of all linebackers is pretty lengthy: They must defend the run and also pressure the quarterback. (Vacating their assigned areas to go after the quarterback is called blitzing.) They must execute stunts and defend against the pass in a zone or in what are paradoxically known as short-deep areas on their side of the line of scrimmage. Also, the middle linebacker generally makes the defensive calls (he informs his teammates of what coverages and alignments they should be in) when the offense breaks its huddle.

Linebackers also are often responsible on pass defense to watch and stay with the tight end and backs. In other pass defense coverages, a linebacker may be responsible for staying with a speedy wide receiver in what’s known as man-to-man coverage (more on this in Chapter 10).

To fully understand linebacker play, you need to be aware that every linebacker wants to coordinate his responsibilities with those of the defensive line. A linebacker is responsible for at least one of the gaps — the lettered open spaces or areas between the offensive linemen — in addition to being asked to ultimately make the tackle.

Every team wants its linebackers to be the leading tacklers on the team. It doesn’t want its players in the secondary, the last line of the defense (see Chapter 10), to end up as the top tacklers, because that means the other team’s running backs have consistently broken through the line.

To keep your sanity when watching a game, just try to remember which players are the linebackers and that the bulk of their job is to do what Patrick Willis of the San Francisco 49ers (shown in Figure 9-8 ) does: make tackles from sideline to sideline and constantly pursue the ball carrier.

To keep your sanity when watching a game, just try to remember which players are the linebackers and that the bulk of their job is to do what Patrick Willis of the San Francisco 49ers (shown in Figure 9-8 ) does: make tackles from sideline to sideline and constantly pursue the ball carrier.

Photo credit: © Michael Zagaris/Getty Images

Figure 9-8: Linebackers like all-pro Patrick Willis of the San Francisco 49ers guard against the run and the pass.

Dealing with the senses

Linebackers must take full advantage of what they can see, feel, and do. Every drill they do in practice, which carries over to the game, is based on these things:

· Eyes: Linebackers must train their eyes to see as much as possible. They must always focus on their target prior to the snap of the ball and then mentally visualize what may occur after the snap.

· Feet: Everything linebackers do involves their ability to move their feet. Making initial reads of what the offense is going to do, attempting to block offensive linemen and defeat them, and tackling the ball carrier are all directly related to proper foot movement.

· Hands: A linebacker’s hands are his most valuable weapons. They also protect him by enabling him to ward off blockers and control the offensive linemen. A linebacker uses his hands to make tackles, recover fumbles, and knock down and intercept passes.

Naming all the linebackers

The following definitions can help you dissect the complex world of the linebacker:

· True linebacker: Linebackers who line up in the conventional linebacker position — behind the defensive linemen — are true linebackers. They align themselves according to the defensive call. Their depth (or distance) from the line of scrimmage varies, but it’s usually 4 yards.

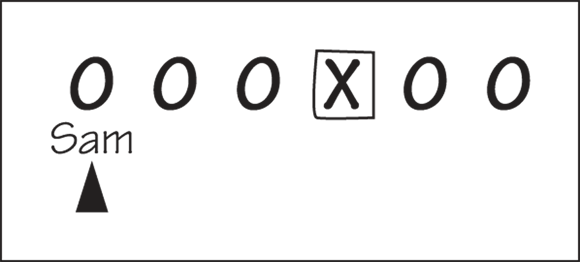

· Sam linebacker: A linebacker who lines up directly across from the tight end (the strong side of the formation) and keys the tight end’s movements, as shown in Figure 9-9 . His responsibility is to disrupt the tight end’s release off the line of scrimmage when he’s attempting to run out for a pass. The linebacker must then react accordingly. Depending on the defensive call, he either rushes the passer or moves away from the line of scrimmage and settles (called a pass drop) into a specified area to defend potential passes thrown his way. The ideal Sam linebacker is tall, preferably 6 feet 4 inches or taller, which enables him to see over the tight end. (Tight ends also tend to be tall.)

When he played with the New York Giants in the 1980s, Carl Banks was a perfect fit for the Sam linebacker position. He had long arms and viselike hands, giving him the ability to control the tight end or shed him (push him away) if he needed to run to a specific side. The Sam linebacker needs to immobilize the tight end as well as have the athletic ability to pursue any ball carrier.

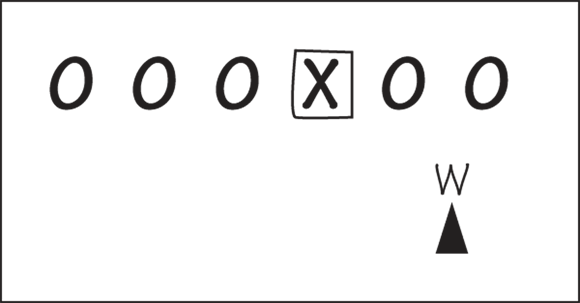

· Willy linebacker: The macho term for a weak-side linebacker (see Figure 9-10 ), the Willy linebacker has the most varied assignments of any linebacker: He rushes the passer or drops into coverage, depending on the defensive call. He tends to be smaller, nimbler, and faster than most other linebackers.

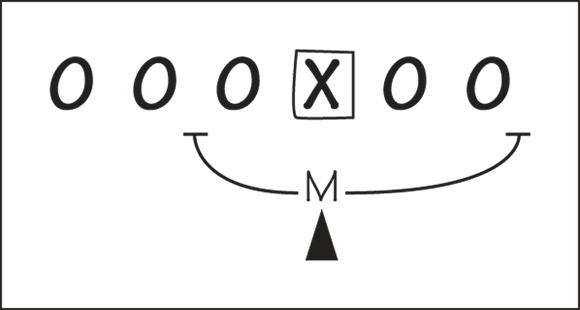

· Mike linebacker: This is the glory position of the linebacker corps. Every defensive player — from boys playing pickup games on the sandlot to men playing in the NFL — wants to play this position. The Mike linebacker is also known as the middle linebacker in 4-3 defenses (which I explain in Chapter 11). He lines up in the middle, generally directly opposite the offense’s center and off him 3 to 4 yards, as shown in Figure 9-11 . His job is to make tackles and control the defense with his calls and directions. He keys the running backs and the quarterback because he’s in the middle of the defense and wants to go where the ball goes.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-9: The Sam linebacker disrupts the tight end during the play.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-10: The Willy linebacker (W) covers the weak side.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 9-11: The Mike linebacker (M) lines up across and back from the center.

Defensive Alignments

To better understand the inner workings of defensive football, you need to know how a defense lines up. Most defenses line up according to where the tight end on offense lines up. A defensive player, generally a linebacker, yells “left” or “right,” and the remaining players react and align themselves. Alignments are critical to a defense’s success. If the defense isn’t in the proper alignment, the players put themselves at a great disadvantage prior to the snap of the ball.

Here are some helpful explanations of terms used to describe defensive players and their alignments:

Here are some helpful explanations of terms used to describe defensive players and their alignments:

· On or over a player: The defensive player is directly across from the offensive player and no more than a yard apart — virtually helmet to helmet.

· Inside a player: The defensive player lines up with his right shoulder across from the offensive player’s right shoulder. The defensive player’s right shoulder can be directly across from the offensive player’s helmet.

· Wide of a player: The defensive player is facing forward, and his entire upper body is outside the nearest shoulder of an offensive player. When the center snaps the ball, the defensive player wants a clear path forward so he can use his quickness to beat the offensive blocker off the line of scrimmage.

· Over defense: In this defensive alignment, four members of the defensive team shift position in order to put themselves directly opposite each player aligned on the strong side (tight end side) of the offensive formation.

· Under defense: This is exactly the opposite of the over shift. This time, three defensive players line up directly across from the center, guard, and tackle on the weak side (non-tight end side) of the offensive formation, leaving only a defensive end opposite the offensive tackle on the strong side of the formation.

The open end side, or weak side, is opposite the tight end, where the split end lines up on offense. Most defenses design their schemes either to the tight end or to the open end side of the field. When linebackers and defensive linemen line up, they do so as a group. For example, they align over to the tight end or maybe under to the open end.

Sacks, Tackles, and Other Defensive Gems

Defensive players work all game hoping to collect a tangible reward: a sack. Former Los Angeles Rams defensive end Deacon Jones coined the term sack in the 1960s when referring to tackling the quarterback for a loss behind the line of scrimmage. (The name comes from hunting: When hunters go into the field planning to shoot a quail or pheasant, they place their trophies in a gunnysack.) Unfortunately for Jones, who had as many as 30 sacks in some of his 14 seasons, the NFL didn’t begin to officially record this defensive statistic until the 1982 season. Consequently, Jones doesn’t appear on the all-time sack leader list, which is headed by Bruce Smith with 200.

When two defensive players tackle the quarterback behind the line of scrimmage, they must share the sack. Each player is credited with half a sack; that’s how valuable the statistic has become. In fact, many NFL players have performance clauses in their contracts regarding the number of sacks they collect, and they receive bonuses for achieving a certain number of sacks.

Unfortunately, in the quest to rack up sacks, defensive players can get penalized for roughing the passer if they’re not careful. The NFL has placed special emphasis on protecting quarterbacks from late hits and unnecessary roughness. Defensive players can no longer strike the quarterback in the head or neck area, even with an incidental, glancing blow. Nor can they tackle quarterbacks at the knee or lower. They must also avoid driving the quarterback into the ground when tackling. The bottom line is you can’t hit 'em high, you can’t hit 'em low, and you can’t hit 'em hard. That makes a pass rusher’s job pretty tough.

Alan Page, Hall of Famer and defensive end of the Minnesota Vikings, was so quick that opposing quarterbacks often rushed their throws in anticipation of being tackled. Some quarterbacks would rather risk throwing an incompletion — or an interception — than be sacked. Page’s coach, Bud Grant, called this action a hurry. The term remains popular in football, and pressuring the quarterback remains the number-one motive of defensive linemen on pass plays.

Alan Page, Hall of Famer and defensive end of the Minnesota Vikings, was so quick that opposing quarterbacks often rushed their throws in anticipation of being tackled. Some quarterbacks would rather risk throwing an incompletion — or an interception — than be sacked. Page’s coach, Bud Grant, called this action a hurry. The term remains popular in football, and pressuring the quarterback remains the number-one motive of defensive linemen on pass plays.

The term tackling has been around for more than 100 years. A player is credited with a tackle when he single-handedly brings down an offensive player who has possession of the ball. Tackles, like sacks, can be shared. A shared tackle is called an assist. Many teams award an assist whenever a defensive player effectively joins in on a tackle. For example, some offensive players have the strength to drag the first player who tries to tackle them. When that occurs, the second defensive player who joins the play, helping to bring down the ball carrier, is credited with an assist.

You may have heard the term stringing out a play. Defenders are coached to force the ball carrier toward the sideline after they cut off the ball carrier’s upfield momentum. Consequently, the sideline may be the best “tackler” in the game.

A lineman who preferred keyboards to QBs

A lineman who preferred keyboards to QBs

Mike Reid was raised in Altoona, Pennsylvania — about the craziest high school football town in the country. Reid became an all-state defensive lineman and a punishing fullback. Before football, his mother made him take piano lessons. So when Penn State offered him a football scholarship, he accepted and majored in classical music.

Reid was a demon on the football field. In 1969, he won the Outland Trophy, emblematic of the best lineman in college football. The next April, he was the first-round draft choice of the Cincinnati Bengals. He enjoyed football, but music remained his passion. He taped his fingers before every game, hoping to prevent them from being broken so that he could play the piano on Monday afternoons. After playing five pro seasons and twice being named to all-pro teams, Reid quit the Bengals in 1975 to join a little-known rock band. Five years later, he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, and began writing country western songs.

Reid has since written such hits as “There You Are” for Willie Nelson and “I Can’t Make You Love Me” for Bonnie Raitt. He has won three Grammys and even wrote an opera about football, titled Different Fields.