Football For Dummies (2015)

Part II

Go, Offense!

Visit www.dummies.com/extras/football for an article on one of the great teams of all time, the 1940-1943 Chicago Bears.

Visit www.dummies.com/extras/football for an article on one of the great teams of all time, the 1940-1943 Chicago Bears.

In this part …

· Find out what it takes to be a quarterback, physically and mentally

· Discover how teams throw and run the ball and compare passing patterns

· Examine offensive strategies and get to know the people who play the ground game

Chapter 4

The Quarterback, Football’s MVP

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding what a quarterback does

Understanding what a quarterback does

![]() Recognizing the qualities that make a good quarterback

Recognizing the qualities that make a good quarterback

![]() Deciphering quarterback language and fundamentals

Deciphering quarterback language and fundamentals

![]() Figuring out a quarterback’s rating

Figuring out a quarterback’s rating

Being a former defensive player, I hate to admit that the quarterback is the most important player on a football team. My only consolation is that although quarterbacks command the highest salaries in the NFL, my fellow defensive linemen are number two on the list. That’s because their job is to make the quarterback’s life miserable. Quarterbacks get all the press during the week, and defensive guys knock the stuffing out of them on weekends.

I like my quarterback to be the John Wayne of the football team. He should be a courageous leader, one who puts winning and his teammates ahead of his personal glory. Joe Montana, who won four Super Bowls with the San Francisco 49ers, and John Elway, who won two Super Bowls with the Denver Broncos, quickly come to mind. Both of them played with toughness, although they also had plenty of talent, skill, and flair to somehow escape the worst situations and throw the touchdown pass that won the game.

I like my quarterback to be the John Wayne of the football team. He should be a courageous leader, one who puts winning and his teammates ahead of his personal glory. Joe Montana, who won four Super Bowls with the San Francisco 49ers, and John Elway, who won two Super Bowls with the Denver Broncos, quickly come to mind. Both of them played with toughness, although they also had plenty of talent, skill, and flair to somehow escape the worst situations and throw the touchdown pass that won the game.

In this chapter, I reveal the fundamental skills necessary for a quarterback. I also discuss stance, vision, and arm strength and solve the puzzle of that mysterious quarterback rating system.

Taking a Look at the Quarterback’s Job

With the exception of kicking plays (described in Chapter 12), quarterbacks touch the ball on every offensive play. A quarterback’s job is to direct his team toward the end zone and score as many points as possible. The typical team scores on one-third of its offensive possessions, resulting in either a touchdown or a field goal. So you can see that the quarterback is under enormous pressure to generate points every time the offense takes the field.

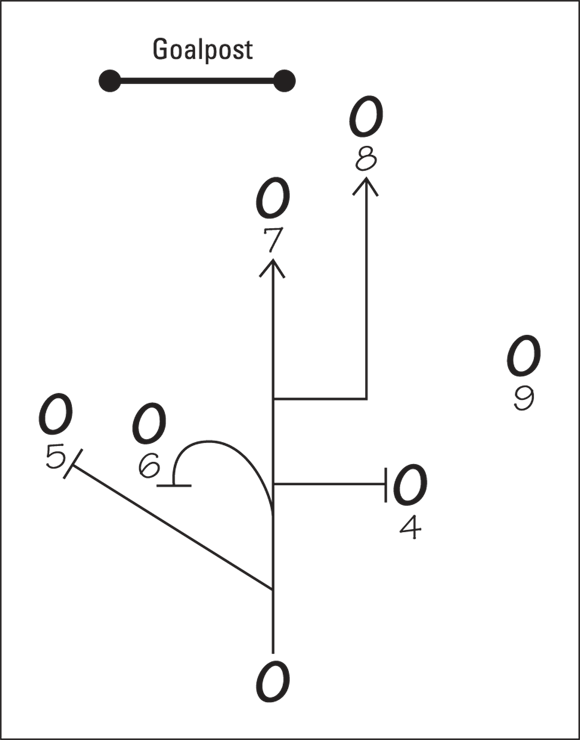

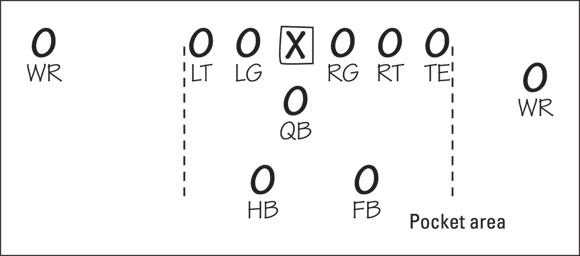

The quarterback (QB) is the player directly behind the center receiving the ball, as shown in Figure 4-1, where the center is the X. He’s the player who announces the plays in the huddle, but he doesn’t call them on his own. Coaches on all levels of football (peewee, high school, college, and the NFL) decide what plays the offense will use.

The QB lines up directly behind the center at the beginning of each play. In the NFL, a quarterback receives plays from a coach on the sidelines via an audio device placed in his helmet. In high school and college football, an assistant coach generally signals in the plays from the sidelines after conferring with the head coach or offensive coordinator. In critical situations, a player may bring in the play when being substituted for an offensive player already on the field.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 4-1:

When Terry Bradshaw, my partner at FOX, played in the NFL in the 1970s, many coaches allowed their veteran quarterbacks to call their own plays after practicing and studying all week. But eventually the coaches wrested control of the play calling away from the quarterbacks, believing that the responsibility was too much of a mental burden for them. When the game became more specialized (with multiple substitutions on both offense and defense) in the 1980s, coaches decided that they wanted the pressure of making the play calls. They didn’t think that a quarterback needed the additional responsibility of facing the media after a game and explaining why he called certain plays in a losing game. Head coaches wanted to be the ones to answer those tough questions.

Although NFL coaches don’t allow quarterbacks to call their own offensive plays (except in no-huddle situations when little time remains on the clock), a player must be prepared to change the play at the line of scrimmage if it doesn’t appear that the play will succeed. Changing the play at the line of scrimmage in this way is called audibilizing (see the later “Calling Plays and Audibilizing” section for more on this topic).

After the quarterback is in possession of the ball, he turns and, depending on which play was called, hands the ball to a running back, runs with the ball himself, or moves further back and sets up to attempt a pass. Depending on the design of the offense, the quarterback takes a three-step, five-step, or seven-step drop before throwing the ball.

The area in which the quarterback operates, most likely with a running back (RB) and the offensive line protecting him from the defense, is called the pocket. It’s as wide as the positioning of the quarterback’s offensive tackles (refer to Figure 4-1). The quarterback is instructed to stay within this so-called protective area; if he ventures out of the pocket, he’s likely to suffer a bone-crushing tackle. And the last thing a coach wants is for his quarterback, the leader of his team, to get injured.

The quarterback’s main job is to throw the football and encourage his teammates to play well. In college, especially if the team runs a spread formation, the quarterback may run the ball as often as he passes, but in the NFL, the quarterback doesn’t run the ball very often unless he’s being chased out of the pocket or instructed to run a quarterback sneak. Teams run this play when the offense needs a yard or less for a first down. In a quarterback sneak, the quarterback takes a direct snap from the center and either leaps behind his center or guard or dives between his guard and center, hoping to gain a first down.

In passing situations when the team has many yards to go for a first down or touchdown, quarterbacks sometimes take a shotgun snap. In this instance, the quarterback stands 6 to 8 yards behind the center and receives the ball through the air from the center much like a punter does. Starting from the shotgun position, the quarterback doesn’t have to drop back. He can survey the defense and target his receivers better. However, defending against a quarterback who lines up in the shotgun position is easier for the defensive players, because they know the play is very likely to be a pass instead of a run.

While the quarterback is setting up a play, he must also be aware of what the defense is attempting to do. Later in this chapter, I explain how quarterbacks “read” a defense.

Determining What a Quarterback Needs to Succeed

When scouts or coaches examine a quarterback’s potential to play in the NFL, they run down a checklist of physical, mental, and personality traits that affect a quarterback’s success on the field. These qualities are required for success at all levels of football. However, in this chapter, I discuss them in terms that relate to a professional athlete.

Note: Some scouts and coaches break down a quarterback’s talent and abilities further, but for this book’s purposes, the following are the main criteria necessary to excel. If a quarterback has five of these eight traits, he undoubtedly ranks among the top 15 players at his position.

Arm strength

Unlike baseball, football doesn’t use a radar gun to gauge the speed of the ball after the quarterback releases it. But velocity is important when throwing a football because it allows a quarterback to complete a pass before a single defensive player can recover (react to the pass) and possibly deflect or intercept the ball. The more arm strength a quarterback has, the better his ability to throw the ball at a high speed.

Many good quarterbacks, with practice, could throw a baseball between 75 and 90 miles per hour, comparable to a Major League Baseball pitcher. Because of its shape, a football is harder to throw than a baseball, but NFL quarterbacks like the Denver Broncos’ Peyton Manning and the New York Jets’ Michael Vick throw the fastest passes at over 45 miles per hour.

Accuracy

Defensive coverage has never been tighter than in today’s NFL. When a receiver goes out into a route, most of the time he’s open for only a tiny window of space and time. The best quarterbacks can put the ball in the ideal spot for the receiver to not only catch the ball but to catch it in stride to gain more yards down field. Elite quarterbacks make the perfect throw play after play. Plenty of quarterbacks have strong arms, but the ones who succeed at the highest levels make their living with accurate throws.

Competitiveness

A player’s competitiveness is made up of many subjective and intangible qualities. A quarterback should have the desire to be the team’s offensive leader and, ideally, overall leader. No one should work harder in practice than he does.

The quarterback’s performance affects the entire offensive team. If he doesn’t throw accurately, the receivers will never catch a pass. If he doesn’t move quickly, the offensive linemen won’t be able to protect him. He also should have the courage to take a hard hit from a defensive player. During games, quarterbacks must cope with constant harassment from the defense. They must stand in the pocket and hold onto the ball until the last split second, knowing that they’re going to be tackled the instant they release the ball.

The quarterback’s performance affects the entire offensive team. If he doesn’t throw accurately, the receivers will never catch a pass. If he doesn’t move quickly, the offensive linemen won’t be able to protect him. He also should have the courage to take a hard hit from a defensive player. During games, quarterbacks must cope with constant harassment from the defense. They must stand in the pocket and hold onto the ball until the last split second, knowing that they’re going to be tackled the instant they release the ball.

To be a competitive player, a quarterback must have an inner desire to win. The quarterback’s competitive fire often inspires his teammates to play harder. Competitiveness is a quality that every coach (and teammate) wants in his quarterback.

Intelligence

The quarterback doesn’t have to have the highest IQ on the team, but intelligence does come in handy. Many NFL teams have a 3-inch-thick playbook that includes at least 50 running plays and as many as 200 passing plays. The quarterback has to know them all. He has to know not only what he’s supposed to do in every one of those plays but also what the other skilled players (running backs, receivers, and tight ends) are required to do. Why? Because he may have to explain a specific play in the huddle or during a timeout. On some teams, the quarterback is also responsible for informing the offensive linemen of their blocking schemes.

Many quarterbacks are what coaches call football smart: They know the intricacies of the game, the formations, and the defenses. They play on instinct and play well. Former San Francisco quarterback Steve Young is both football smart and book smart. Young was a lot like former great quarterbacks Otto Graham of the Cleveland Browns and Roger Staubach of the Dallas Cowboys. Being book smart and football smart can be an unbeatable combination on game days.

Many quarterbacks are what coaches call football smart: They know the intricacies of the game, the formations, and the defenses. They play on instinct and play well. Former San Francisco quarterback Steve Young is both football smart and book smart. Young was a lot like former great quarterbacks Otto Graham of the Cleveland Browns and Roger Staubach of the Dallas Cowboys. Being book smart and football smart can be an unbeatable combination on game days.

Mobility

A quarterback’s mobility is as important as his intelligence and his arm. He must move quickly to avoid being tackled by defensive players. Therefore, he must move backward (called retreating) from the center as quickly as possible in order to set himself up to throw the ball. When a quarterback has excellent mobility, you hear him described as having quick feet. This term means that he moves quickly and effortlessly behind the line of scrimmage with the football. A quarterback doesn’t have to be speedy to do this. He simply must be able to maneuver quickly and gracefully. In one simple step away from the line of scrimmage, a good quarterback covers 4½ feet to almost 2 yards. While taking these huge steps, the quarterback’s upper body shouldn’t dip or lean to one side or the other. He must be balanced.

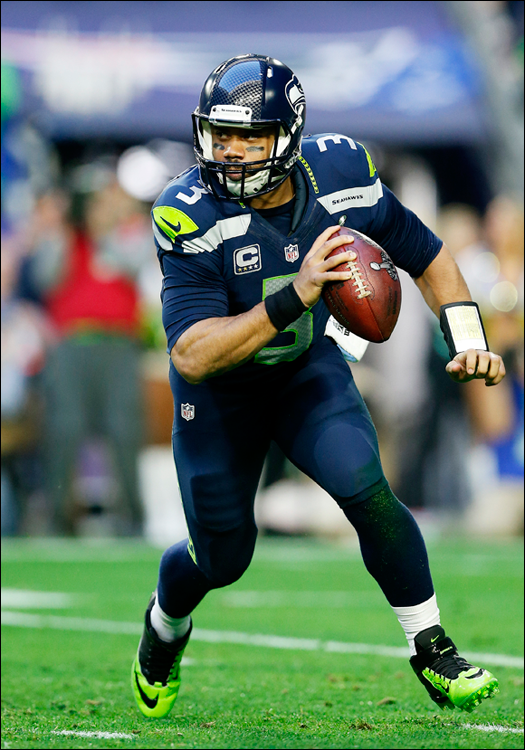

Mobility is also critical when a quarterback doesn’t have adequate pass protection and has to move out of the pocket and pass while under pressure and on the run. Coaches call this type of mobility escapability. Both Michael Vick and Russell Wilson, shown in Figure 4-2, are great at escaping defensive pressure. Maybe the best of the old-timers was Fran Tarkenton, who played with the New York Giants and the Minnesota Vikings. Roger Staubach of the Cowboys was nicknamed “Roger the Dodger” because he was tough to trap.

Photo credit: © Joe Robbins/Getty Images

Figure 4-2: Quarterback Russell Wilson of the Seattle Seahawks is one of the more mobile quarterbacks in the NFL.

Release

If a quarterback doesn’t have exceptional arm strength, he’d better have a quick release. After the quarterback raises the ball in his hand, usually near his head or slightly above and behind it, he releases, or rapidly brings his arm forward and lets the ball loose. Former Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino probably had the game’s quickest release. His arm and hand remained a blur when filmed and replayed in slow motion.

Quarterbacks with great releases generally are born with the ability. Average quarterbacks can improve and refine their releases, but their releases will never be great. A quarterback either has this coordinated motion between his arm, elbow, and wrist, or he doesn’t. Throwing a football isn’t a natural arm movement like slinging your arm to roll a bowling ball.

Size

Players of all different heights and weights have played the quarterback position, but NFL quarterbacks are preferably over 6'1" and 210 pounds. A quarterback who’s 6'5" and 225 pounds is considered ideal. A quarterback wants to be tall enough to see over his linemen — whose average height in the NFL is 6'5" to 6'7" — and look down the field, beyond the line of scrimmage, to find his receivers and see where the defensive backs are positioned.

Weight is imperative to injury prevention because of the physical wear and tear that the quarterback position requires. A quarterback can expect a lot of physical contact, especially when attempting to pass. Defenders relentlessly pursue the quarterback to hit him, tackling him for a sack (a loss of yards behind the line of scrimmage) before he can throw a pass or making contact after he releases a pass. These hits are sometimes legal and sometimes illegal. If the defensive player takes more than one step when hitting the quarterback after he releases the ball, the hit is considered late and therefore illegal. Regardless, defensive linemen and linebackers are taught to inflict as much punishment as possible on the quarterback. They want to either knock him out of the game or cause him enough pain that he’ll be less willing to hold on to the ball while waiting for his receivers to get open. When a quarterback releases a pass prematurely, it’s called bailing out of the play.

Vision

A quarterback doesn’t necessarily need keen peripheral vision, but it doesn’t hurt. A quarterback must quickly scan the field when he comes to the line of scrimmage prior to the snap of the ball. He must survey the defense, checking its alignments and in particular the depth of the defensive backs — how far they are off the receivers, off the line of scrimmage, and so on. After the ball is snapped, the quarterback must continue to scan the field as he moves backward. Granted, he may focus on a particular area because the play is designed in a certain direction, but vision is critical if he wants to discover whether a receiver other than his first choice is open on a particular play. Most pass plays have a variety of options, known as passing progressions. One pass play may have as many as five players running pass routes, so the quarterback needs to be able to check whether any of them is open so that he has an option if he’s unable to throw to his intended (first choice) receiver.

A quarterback needs to have a sense of where to look and how to scan and quickly react. Often, a quarterback has to make a decision in a split second or else the play may fail. Vision doesn’t necessarily mean that the quarterback has to jerk his head from side to side. Instead, his passing reads (how a quarterback deciphers what the defense is attempting to accomplish against the offense on a particular play) often follow an orderly progression as he looks across the field of play. A quarterback must have an understanding of what the defensive secondary’s tendencies are — how they like to defend a particular play or a certain style of receiver. Sometimes, after sneaking a quick glance at his intended target, the quarterback looks in another direction in order to fool the defense. (Many defensive players tend to follow a quarterback’s eyes, believing that they’ll tell where he intends to throw the pass.)

Quarterbacking Fundamentals

Playing quarterback requires a lot of technical skills. Although a coach can make a player better in many areas of the game, I don’t believe that any coach can teach a player how to throw the football. Otherwise, every quarterback would be a great passer. And if such a coach existed, every father would be taking his son to that coach, considering the millions of dollars NFL quarterbacks earn every season.

You can teach a quarterback how to deal with pressure, how to make good decisions, and how to make good connections with his receivers and predict where they’ll be. But quarterbacks either have the innate talent to throw the football — that natural arm motion and quick release — or they don’t. Think of how many good college quarterbacks fail to survive in the NFL. Plus, NFL scouts, coaches, general managers, and so on will tell you that the league has only 10 to 15 really good quarterbacks. If throwing could be taught, all quarterbacks would be great.

You can teach a quarterback how to deal with pressure, how to make good decisions, and how to make good connections with his receivers and predict where they’ll be. But quarterbacks either have the innate talent to throw the football — that natural arm motion and quick release — or they don’t. Think of how many good college quarterbacks fail to survive in the NFL. Plus, NFL scouts, coaches, general managers, and so on will tell you that the league has only 10 to 15 really good quarterbacks. If throwing could be taught, all quarterbacks would be great.

Quarterbacks can improve and refine their skills in the following areas with a lot of practice and hard work.

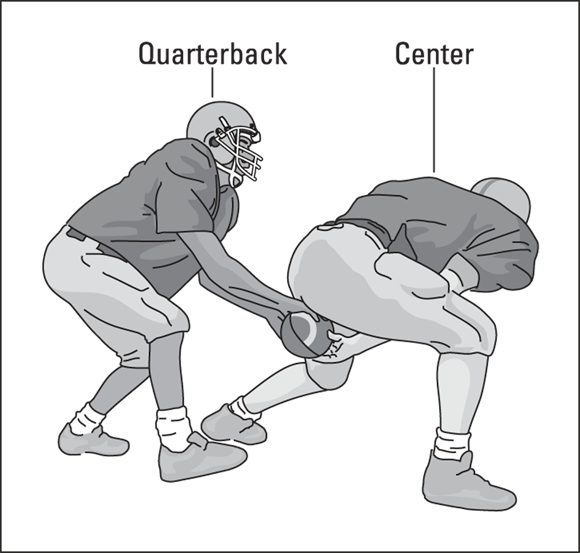

Settling into the stance

To play the most important position in football, a quarterback must begin with his stance under center. The quarterback takes his stance behind the center to receive the ball; the center snaps it back to him, as shown in Figure 4-3. The quarterback’s stance under center starts with both feet about shoulder width apart. He bends his knees, flexes down, and bends forward at the waist until he’s directly behind the center’s rear end. The quarterback then places his hands, with the thumbs touching each other and the fingers spread as far apart as possible, under the center’s rear end. Because some centers don’t bring the ball all the way to the quarterback’s hands, the quarterback will lower his hands below the center’s rear end in order to receive the ball cleanly. The quarterback needs to avoid pulling out early, a common mistake when the quarterback and the center haven’t played together very much.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 4-3: A quarterback usually lines up behind the center, who snaps the ball to him to start the play.

Dropping back

After he masters the stance, a quarterback learns how to drop back and set up to pass. Dropping back is what a quarterback does after he receives the ball from the center. Before he passes the ball, he must move away from the line of scrimmage (and the opposing defense) and put himself in a position to be able to throw the football.

You see quarterbacks backing up from center, or backpedaling, when the offensive formation is aligned to the left of a right-handed quarterback. Backpedaling is essential in those alignments so that the quarterback can see whether the linebacker on that side is blitzing (rushing across the line of scrimmage in an attempt to tackle the quarterback). The quarterback must be alert to a possible blitz; consequently, he can’t afford to half-turn his back to that side.

The depth to which a quarterback drops in the pocket generally is determined by how far from the line of scrimmage the receiver is running. If the receiver is running 5 to 6 yards down the field and then turning to catch the ball, for example, the quarterback takes a drop of no more than three steps. The quarterback generally moves further away from the line of scrimmage as the pass routes (the paths receivers take when going out for a pass) of his receivers get longer. For instance, if the receiver is running 10 to 12 yards down the field, the quarterback takes five steps to put himself about 7 yards back from the line of scrimmage.

On a post route (a deep pass in which the receiver angles in to the goalpost) or a streak route (a deep pass straight downfield), the quarterback takes a seven-step drop. Taking a longer drop when a shorter one is required enables the defense to recover and may lead to an interception or an incompletion.

All these drop-backs are critical to the timing of the receiver’s run, move, and turn and the quarterback’s delivery and release. In practice, the quarterback works on the depth of his steps according to the pass route.

Handing off

One of the most important things for a quarterback to master is the running game and how it affects his steps from center (head to Chapter 6 for the scoop on the running game). Some running plays call for the quarterback to open his right hip (if he’s right-handed) and step straight back. This technique is called the six o’clock step. The best way to imagine these steps is to picture a clock. The center is at twelve o’clock, and directly behind the quarterback is six o’clock. Three o’clock is to the quarterback’s right, and nine o’clock is to his left.

For example, a right-handed quarterback hands off the ball to a runner heading on a run around the left side of his offensive line (it’s called a sweep) at the five o’clock mark. When handing the ball to a runner heading on a sweep across the backfield to the right, the quarterback should hand off at the seven o’clock mark.

Getting a grip

Because different quarterbacks have different-sized hands, one passing grip doesn’t suit everyone. Some coaches say that a quarterback should hold the ball with his middle finger going across the ball’s white laces or trademark. Other coaches believe both the middle and ring finger should grip the laces.

Many great quarterbacks have huge hands, allowing them to place their index finger on the tip of the ball while wrapping their middle, ring, and small fingers around the middle of the ball. However, the ball slips from many quarterbacks’ hands when they attempt to grip the ball this way. So, basically, every quarterback needs to find the grip that works for him.

Reading a Defense

When a quarterback prepares for a game, he wants to be able to look at a specific defensive alignment and instantly know which offense will or won’t succeed against it.

Many quarterbacks are taught to read the free safety, or the safety positioned deepest in the secondary, the part of the field behind the linebackers that the safeties and cornerbacks are responsible for. (See Chapter 10 for more on the secondary and Chapter 11 for the full scoop on defensive schemes and strategies.) If the free safety lines up 5 to 7 yards deeper than the other defensive backs, the safeties are probably playing a zone defense. A quarterback also knows that the defense is playing zone if the cornerbacks are aligned 10 yards off the line of scrimmage. If the cornerbacks are on the line of scrimmage, eyeballing the receivers, they’re most likely playing man-to-man. Knowing whether the defense is playing zone or man-to-man is important to the quarterback because he wants to know whether he’s attacking a zone defense or man-to-man alignment with his pass play.

Although a defense may employ 20 to 30 different pass coverages in the secondary, four basic coverages exist. Because most defenses begin with four players in the secondary, the coverages are called cover one, cover two, cover three, and cover four. The following list gives a description of each:

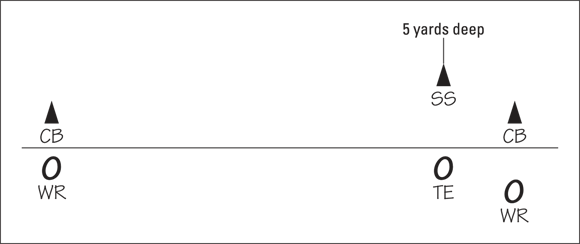

· Cover one: In this coverage, shown in Figure 4-4, one deep safety is about 12 to 14 yards deep in the middle of the field, the two cornerbacks (CB) are in press coverage (on the line of scrimmage opposite the two receivers), and the strong safety (SS) is about 5 yards deep over the tight end. Cover one is usually man-to-man coverage. A running play works best against this type of coverage.

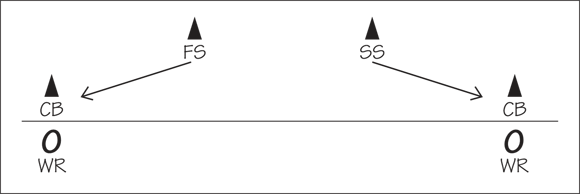

· Cover two: This time, both safeties are deep, 12 to 14 yards off the line of scrimmage, as shown in Figure 4-5. The two cornerbacks remain in press coverage, while the two safeties prepare to help the corners on passing plays and come forward on running plays. A deep comeback pass, a crossing route, or a swing pass works well against this type of coverage.

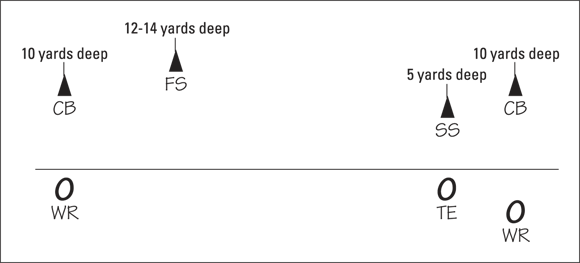

· Cover three: This coverage, shown in Figure 4-6, has three defensive backs deep. The free safety remains 12 to 14 yards off the line of scrimmage, and the two cornerbacks move 10 to 12 yards off the line of scrimmage. Cover three is obvious zone coverage. The strong safety is 5 yards off the line of scrimmage, over the tight end. This cover is a stout defense versus the run, but it’s soft against a good passing team. In this cover, a quarterback can throw underneath passes (short passes to beat the linebackers who are positioned underneath the defensive back’s coverage). Staying with faster receivers in this area is difficult for some linebackers to do.

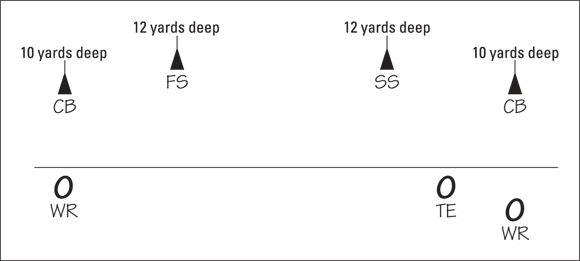

· Cover four: In cover four, what you see is what you get, as shown in Figure 4-7. All four defensive backs are off the line of scrimmage, aligned 10 to 12 yards deep. Some teams call this coverage “Four Across” because the defensive backs are aligned all across the field. The cover four is a good pass defense because the secondary players are told to never allow a receiver to get behind them. If offensive teams can block the front seven (a combination of defensive linemen and linebackers that amounts to seven players), a running play works against this coverage.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 4-4: Cover one puts one safety or secondary player close to the line while the free safety (not pictured) plays deep.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 4-5: Cover two puts both safeties deep.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 4-6: In cover three, three defensive backs line up deep.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 4-7: Cover four aligns all four secondary players off the line of scrimmage.

Calling Plays and Audibilizing

The quarterback relays to his teammates in the huddle what play the coach has called. The play is a mental blueprint or diagram for every player on the field. And everything the quarterback says refers specifically to the assignments of his receivers, running backs, offensive linemen, and center.

For example, the quarterback may say “686 Pump F-Stop on two.” The first three numbers (686) are the passing routes that the receivers — known as X, Y, and Z — should take. Every team numbers its pass routes and patterns (look for them in Chapter 5), giving receivers an immediate signal of what routes to run. On this play, the X receiver runs a 6 route, the Y receiver an 8 route, and the Z receiver another 6 route. “F-Stop” in this case refers to the fullback’s pass route. And “two” refers to the count on which the quarterback wants the ball snapped to him. In other words, the center will snap the ball on the second sound.

Most teams snap the ball on the first, second, or third count unless they’re purposely attempting to draw the opposition offside by using an extra-long count. For example, if the quarterback has been asking for the ball on the count of two throughout the game, he may ask for the ball on the count of three, hoping that someone on the defense will move prematurely.

After the quarterback reaches the line of scrimmage and puts his hands under the center, he says “Set” (at which point the linemen drop into their stances) and then something like “Green 80, Green 80, Hut-Hut.” The center snaps the ball on the second “Hut.” “Green 80” means absolutely nothing in this case. However, sometimes the quarterback’s remarks at the line of scrimmage prior to the snap count inform his offensive teammates of how the play will be changed. The offensive linemen also know that the play is a pass because of the numbering system mentioned at the beginning of the called play.

Teams give their plays all sorts of odd monikers, such as Quick Ace, Scat, Zoom, and Buzz. These names refer to specific actions within the play; they’re meant for the ears of the running backs and receivers. Each name (and every team has its own terms) means something, depending on the play called.

Quarterbacks are allowed to audibilize, or change the play at the line of scrimmage. A changed play is called an audible. Quarterbacks usually audibilize when they discover that the defense has guessed correctly and is properly aligned to stop the play. When he barks his signals, the quarterback simply has to say “Green 85,” and the play is altered to the 85 pass play. Usually, the quarterback informs his offensive teammates in the huddle what his audible change may be.

Quarterbacks are allowed to audibilize, or change the play at the line of scrimmage. A changed play is called an audible. Quarterbacks usually audibilize when they discover that the defense has guessed correctly and is properly aligned to stop the play. When he barks his signals, the quarterback simply has to say “Green 85,” and the play is altered to the 85 pass play. Usually, the quarterback informs his offensive teammates in the huddle what his audible change may be.

A quarterback may also use an offensive strategy known as check with me, in which he instructs his teammates to listen carefully at the line of scrimmage because he may call another play, or his call at the line of scrimmage will be the play. To help his teammates easily understand, the play may simply change colors — from Green to Red, for example.

Acing Quarterback Math

Quarterbacks are judged statistically on all levels of football by their passing accuracy (which is called completion percentage), the number of touchdowns they throw, the number of interceptions they throw, and the number of yards they gain by passing. This last statistic — passing yards — can be deceiving. For example, if a quarterback throws the ball 8 yards beyond the line of scrimmage and the receiver runs for another 42 yards after catching the ball, the quarterback is awarded 50 yards for the completion. (You may hear television commentators use the term yards after the catch to describe the yards that the receiver gains after catching the ball.) Quarterbacks also receive positive passing yards when they complete a pass behind the line of scrimmage — for example, a screen pass to a running back who goes on to run 15 yards. Those 15 yards are considered passing yards.

For a better understanding of what the quarterback’s numbers mean, take a look at Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning’s statistics for the 2013 season. He played in all 16 regular-season games.

For a better understanding of what the quarterback’s numbers mean, take a look at Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning’s statistics for the 2013 season. He played in all 16 regular-season games.

|

Att |

Comp |

Pct Comp |

Yds |

Yds/Att |

TD |

Int |

Rating |

|

659 |

450 |

68.3 |

5,477 |

8.3 |

55 |

10 |

115.1 |

Examining Manning’s statistics, you see that he attempted 659 passes (Att) and completed 450 of those passes (Comp) for a completion percentage of 68.3 (Pct Comp). In attempting those 659 passes, his receivers gained 5,477 yards (Yds), which equals an average gain per attempt of 8.3 yards (Yds/Att). Manning’s teammates scored 55 touchdowns (TD) via his passing while the defense intercepted (Int) 10 of his passing attempts.

When you see a newspaper article about a football game, the story may state that the quarterback was 22 of 36, passing for 310 yards. Translation: He completed 22 of 36 pass attempts and gained 310 yards on those 22 completions. Not a bad game.

Last but not least you have the NFL quarterback rating formula, also called the passer rating formula. It makes for an unusual math problem. Grab your calculator and follow these steps to figure it out:

1. Divide completed passes by pass attempts, subtract 0.3, and then divide by 0.2.

2. Divide passing yards by pass attempts, subtract 3, and then divide by 4.

3. Divide touchdown passes by pass attempts and then divide by 0.05.

4. Divide interceptions by pass attempts, subtract that number from 0.095, and divide the remainder by 0.04.

The sum of each step can’t be greater than 2.375 or less than zero. Add the sums of the four steps, multiply that number by 100, and divide by 6. The final number is the quarterback rating, which in Manning’s case is 115.1.

A rating of 100 or above is considered very good; an average rating is in the 80 to 100 range, and anything below 80 is considered a poor quarterback rating.

A rating of 100 or above is considered very good; an average rating is in the 80 to 100 range, and anything below 80 is considered a poor quarterback rating.