Football For Dummies (2015)

Part I

Getting Started with Football

Chapter 3

Them’s the Rules (And Regulations)

In This Chapter

![]() Keeping time in a game, starting with the kickoff

Keeping time in a game, starting with the kickoff

![]() Understanding the down system

Understanding the down system

![]() Scoring via touchdowns, field goals, and other methods

Scoring via touchdowns, field goals, and other methods

![]() Defining the officials’ roles and interpreting their signals

Defining the officials’ roles and interpreting their signals

![]() Calling penalties, from offside to personal fouls

Calling penalties, from offside to personal fouls

Football is a pretty complicated game. Twenty-two players are on the field at all times, plus a host of officials, not to mention all those people running around on the sidelines. But after you figure out who’s supposed to be where, and what they’re supposed to do there, following a football game is pretty easy.

This chapter walks you through all the phases of a game, from the coin toss to the opening kickoff to halftime to the time when the fat lady sings. It also explains how the clock works, how you score points, what the officials do, what every penalty means, and much more.

The Ins and Outs of the Game Clock

To keep things in small, easily digestible chunks, every football game is divided into quarters. In college and pro football, each quarter lasts 15 minutes; high school teams play 12-minute quarters. After the second quarter comes halftime, which lasts 12 minutes in the NFL, 15 minutes in college, and 15 to 20 minutes in high school. Halftime gives players time to rest and bands and cheerleaders time to perform (it also gives fans time to go get a hot dog). Coaches, players, or alumni are sometimes honored at halftime.

The game clock, which is operated by a timekeeper in the press box, doesn’t run continuously throughout those 15- or 12-minute quarters. (If it did, when would they show the television commercials?) The clock stops for the following reasons:

The game clock, which is operated by a timekeeper in the press box, doesn’t run continuously throughout those 15- or 12-minute quarters. (If it did, when would they show the television commercials?) The clock stops for the following reasons:

· Either team calls a timeout. Teams are allowed three timeouts per half.

· A quarter ends. The stoppage in time enables teams to change which goal they will defend (they change sides at the end of the first and third quarters).

· The quarterback throws an incomplete pass.

· The ball carrier goes out of bounds.

· A player from either team is injured during a play.

· An official signals a penalty by throwing a flag. (I tell you all about penalties in the later “Penalties and Other Violations” section.)

· The officials need to measure whether the offense has gained a first down, or they need to take time to spot (or place) the ball correctly on the field.

· Either team scores a touchdown, field goal, or safety. (I explain what these achievements are and how much they’re worth in the later “Scoring Points” section.)

· The ball changes possession via a kickoff, a punt, a turnover, or a team failing to advance the ball 10 yards in four downs.

· The offense gains a first down (college and high school only).

· Two minutes remain in the half or in overtime (NFL only).

· A coach has challenged a referee’s call, and the referees are reviewing the call (college and NFL only).

· A wet ball needs to be replaced with a dry one.

Unlike college and professional basketball, where a shot clock determines how long the offense can keep possession of the ball, in football the offense can keep the ball as long as it keeps making first downs (which I explain a little later in this chapter). However, the offense has 40 seconds from the end of a given play, or a 25-second interval after official stoppages, to get in proper position after an extremely long gain. If the offense doesn’t snap the ball in that allotted time, it’s penalized 5 yards and must repeat the down.

Unlike college and professional basketball, where a shot clock determines how long the offense can keep possession of the ball, in football the offense can keep the ball as long as it keeps making first downs (which I explain a little later in this chapter). However, the offense has 40 seconds from the end of a given play, or a 25-second interval after official stoppages, to get in proper position after an extremely long gain. If the offense doesn’t snap the ball in that allotted time, it’s penalized 5 yards and must repeat the down.

With the exception of the last two minutes of the first half and the last five minutes of the second half of an NFL game, the officials restart the game clock after a kickoff return, after a player goes out of bounds on a play, or after a declined penalty.

Overtime and sudden death

If a game is tied at the end of regulation play, the game goes into overtime. To decide who gets the ball in overtime, team captains meet at the center of the field for a coin toss. The team that wins the toss gets the ball and the first crack at scoring.

· In the NFL, this method of handling tie games is sometimes called sudden death because, in regular season play, the game is over immediately after the first team scores. The sudden-death method of deciding a tie game has been criticized as unfair to the team that loses the coin toss. After all, if your team loses the toss, it may not get a chance to get the ball or score. Critics of the overtime system claim that both teams should get the ball and a chance to score in overtime. To calm the critics, the NFL instituted a new overtime policy in 2010. Now if the team that wins the coin toss scores only a field goal during its first possession, the opposing teams gets a crack at scoring too, and if this team scores a touchdown, it wins the game. If the game is still tied after both teams have had a chance to score, the game goes into sudden death, and the first team to score wins.

· Under college rules, each team gets the ball for alternate possessions starting at the 25-yard line. If the team that wins the coin toss scores, its opponent still gets a chance to score and tie the game again. If a college football game goes past two overtimes, teams must try for two-point conversions after touchdowns (instead of kicking for an extra point — a PAT) until one prevails. (See the later section “Extra points and two-point conversions” for additional information on PAT kicks versus going for two.)

The Coin Toss and Kickoff

Every football contest starts with a coin toss. Selected members of each team (called captains) come to the center of the field, where the referee holds a coin. In the NFL, the coin toss is restricted to three captains from each team. In college football, four players may participate. However, only one player from the visiting team calls heads or tails, and that player must do so before the official tosses the coin into the air (hence the name coin toss). If that player calls the toss correctly, his team gets to choose one of three privileges:

· Which team receives the kickoff: Generally, teams want to start the game on offense and have the opportunity to score as early as possible, so the team who wins the toss usually opts to receive. They’re known as the receiving team. The referee, swinging his leg in a kicking motion, then points to the other team’s captains as the kicking team.

· Which goal his team will defend: Instead of receiving the kickoff, the captain may elect to kick off and choose a goal to defend. Captains sometimes take this option if they believe that weather will be a factor in the outcome of the game. For example, in choosing which goal to defend, the player believes that his team will have the wind at its back for the second quarter and the crucial final quarter of the game.

· When to decide: The team that wins the coin flip can defer, giving it the right to choose between kicking and receiving the second-half kickoff.

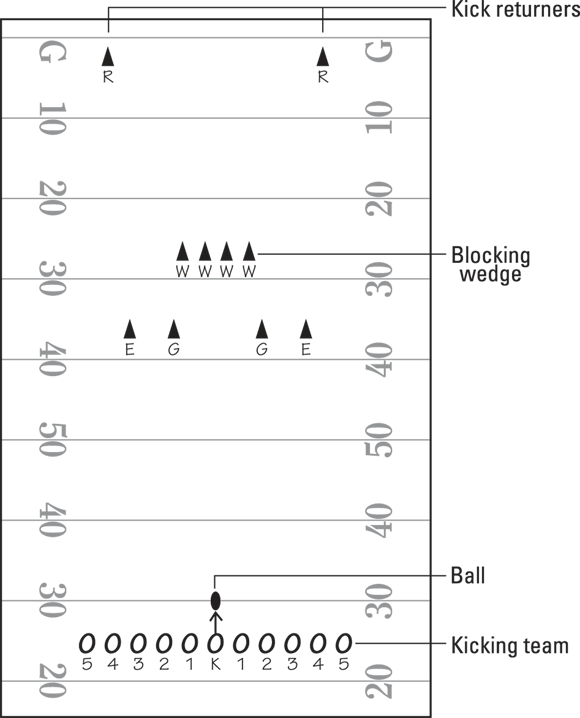

The team that earns the right to receive the ball gets the ball via a kickoff. To perform this kickoff, the kicking team’s placekicker places the ball in a holder (called a tee, which is 1 inch tall in the NFL and 2 inches tall in high school and college) on his team’s 35-yard line (NFL and college), or 40-yard line (high school). The kicker then runs toward the ball and kicks it toward the other team. Figure 3-1 shows how teams typically line up for a kickoff in the NFL.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-1: Players line up in this formation for a kickoff in the NFL.

At the far end of the field from the kicker, one or more returners from the other team await the kickoff. The returner’s goal is to catch the ball and score a touchdown or run the ball as far back toward the opponent’s goal line as he can. After the return is complete, the first set of downs begins.

Downs Plus Yardage Equals Excitement

Watching a game in which the offense keeps running plays but never goes anywhere would be really boring. To prevent that, the fathers of football created the down system. The offense has four downs (essentially four plays) to go 10 yards. If the offensive team advances the ball at least 10 yards in four tries or fewer, it receives another set of four downs. If the offense fails to advance 10 yards after three tries, it can either punt the ball on the fourth down (a punt is a kick to the opponent without the use of a tee) or, if it needs less than a yard to get a first down, try to get the first down by running or passing.

You may hear television commentators use the phrase “three and out.” What they mean is that a team failed to advance the ball 10 yards and has to punt the ball. You don’t want your team to go three and out very often. But you do want to earn lots of first downs, which you get after your team advances the ball 10 yards or more in the allotted four downs. Getting lots of first downs usually translates to more scoring opportunities.

Football has its own lingo to explain the offense’s progress toward a first down. A first down situation is also known as a “first and 10,” because the offense has 10 yards to go to gain a first down. If your offense ran a play on first down in which you advanced the ball 3 yards, your status would be “second and 7”; you’re ready to play the second down, and you now have 7 yards to go to gain a first down. Unless something really bad happens, the numbers stay under 10, so the math is pretty simple.

As a viewer, you aren’t expected to remember what down it is and how many yards the offense needs to advance to gain a first down. Football makes it easy by providing people and signs to help you keep track. On the sideline opposite the press box is a group of three people, known as the chain gang or chain crew, who hold three 8-foot-high poles. Here’s an explanation of that crew:

As a viewer, you aren’t expected to remember what down it is and how many yards the offense needs to advance to gain a first down. Football makes it easy by providing people and signs to help you keep track. On the sideline opposite the press box is a group of three people, known as the chain gang or chain crew, who hold three 8-foot-high poles. Here’s an explanation of that crew:

· Two people called rodmen hold metal rods with Xs at the top connected by a thin metal chain that stretches exactly 10 yards when the two rods are thoroughly extended. One rod marks where the possession begins, and the other extends to where the offensive team must go in order to make another first down.

· The third person, known as the boxman, holds a marker that signifies where the ball is and what down it is. Atop this rod is the number 1, 2, 3, or 4, designating whether it is the first, second, third, or fourth down.

· In all NFL stadiums, a person also marks where the drive began (that is, where the offensive team assumed possession of the ball). Many high school and college fields don’t have these markers.

Whenever the officials need to make a critical measurement for a first down, the chain crew comes to the hash marks nearest where the ball is positioned, and the officials use the rods to measure whether the offense has obtained a first down. The home team supplies the chain crew and also the ball boys, who are responsible for keeping the balls clean and free of excessive moisture.

Thanks to the miracle of technology, determining where a team has to advance the ball to get a first down is easier than ever — but only if you’re watching television. On the television screen during a game, you see an electronic line across the field that marks where a team must go to get a first down.

Scoring Points

Teams can score points in several ways — and scoring more points than the other team is the object of the game. The following sections explain each method of scoring.

Touchdowns

A touchdown is worth six points — the ultimate goal. A team scores a touchdown, plus the loudest cheers from fans, when an offensive player carrying the ball, or a defensive player who has obtained the ball from the other team after recovering a fumble or intercepting a pass, advances from anywhere on the field and breaks the plane of his opponent’s goal line with the ball. (Breaking the plane means that a ball carrier can soar over the goal line in midair and have his efforts count for a touchdown — even if he’s hit in midair and lands back on the 1-yard line — as long as the ball crosses the plane.) Figure 3-2 shows New Orleans Saints’ running back Pierre Thomas scoring a touchdown in the Super Bowl.

Photo credit: © Elsa/Getty Images

Figure 3-2: Pierre Thomas of the New Orleans Saints scores a touchdown against the Indianapolis Colts in Super Bowl XLIV.

A team is also awarded a touchdown when any player who’s inbounds catches or recovers a loose ball behind his opponent’s goal line. This sort of touchdown can occur on a kickoff, a punt, or a fumble (when a player drops the ball).

Extra points and two-point conversions

A try for an extra point, also known as a point after touchdown (PAT), is attempted during the scrimmage down that’s awarded after a touchdown. The extra point is successful when the kicker kicks the ball between the uprights of the goalpost and above the crossbar, provided that the ball was snapped 2 yards away from the opponent’s goal line (or 3 yards away in high school and college). Teams almost always make their extra point attempts — especially beyond the high school level — because the kick is a fairly easy one. (See Chapter 2 for more information about the goalposts.)

When a team is feeling particularly confident — or desperate — it might attempt a two-point conversion after scoring a touchdown. (Chapter 8 talks about situations in which a coach might decide to have his team “go for two.”) Two-point conversions, which were added to the NFL for the 1994 season, have always been a part of high school and college football. The offense gets the ball on the 2-yard line (the 3-yard line in high school and college) and must advance the ball across the goal line, or break the plane, as if scoring a touchdown. In the NFL, the try (called a conversion attempt) is over when the officials rule the ball dead or if a change of possession occurs (meaning the defense intercepts a pass or recovers a fumble). In college, the defensive team can return a fumble or interception to its opponent’s end zone and score two points.

An extra point experiment

In the preseason games of the 2014 season, the NFL moved the spot where extra points are kicked from the 2-yard line to the 15-yard line, making the kick 33 yards. (Two-point conversion attempts remained at the 2-yard line.) The reason for this experiment was to see if the game would be impacted at all if extra points were made more difficult. As the game currently stands, 99.6 percent of extra point attempts are good. Well, in the 2014 preseason, the success rate dropped slightly to 94.3 percent. So increasing the distance of the extra point attempt didn’t really make a difference.

The league will likely continue to experiment with rule changes involving extra points and two-point conversions. Many fans of the game think that extra points are too easy and that two-point conversions should be attempted more often.

Field goals

A field goal, often the consolation prize for an offense that tries to score a touchdown but stalls within its opponent’s 30-yard line, is worth three points. A team scores a field goal when a kicker boots the ball entirely through the uprights of the goalpost without the ball touching either the ground or any of the offensive players. The kicked ball must travel between the uprights and above the crossbar of the goalpost.

You get the distance of a field goal by adding 10 yards (the distance from the goal line to the end line where the goalposts are placed) to the yard line from which the ball is kicked. Or simply add 17 to the number of yards that the offense would have to advance to cross the goal line (the extra 7 yards represents the typical distance of a snap for a field goal attempt). For example, if the offense is on its opponent’s 23-yard line, they’re attempting a 40-yard field goal.

Safeties

A safety occurs when a player on the offensive team is tackled in his own end zone or goes out of bounds in his own end zone. A safety scores two points for the defensive team. After a safety, the team that was scored on must punt the ball to the other team from its own 20-yard line. For the offensive team, a safety is bad thing. The other team gets not only two points but also the ball in good field position. Normally, teams kick off from the 35-yard line. Having to punt from the 20-yard line allows the other team to advance the ball further up the field after the punt.

Frankly, a safety is embarrassing to the offense, and offensive players will do just about anything to prevent a safety. Besides being tackled in the end zone, here are other instances when a safety is awarded:

· A quarterback knows he’s about to be tackled in his end zone, and to prevent the other team from scoring a safety, he chucks the ball out of bounds. If a referee thinks the quarterback threw the pass solely to prevent a safety, the referee awards the safety to the defensive team.

· The offensive team commits a penalty (say, holding a defensive player who’s preparing to tackle the ball carrier in the end zone) that would otherwise require it to have the ball marked in its own end zone.

· A blocked punt goes out of the kicking team’s end zone.

· The receiver of a punt muffs the ball and then, when trying to retrieve the ball, forces or illegally kicks it into the end zone and it goes out of the end zone.

· A muffed ball is kicked or forced into the end zone and then recovered there by a member of the receiving team.

The Role of the Officials

Officials play many important roles in a football game. In fact, they basically have control of every game. For example:

· They’re responsible for any decision involving the application of a rule, its interpretation, or its enforcement.

· They keep players from really hurting each other and making other illegal actions.

· They enforce and record all fouls and monitor the clock and all timeouts that are charged.

All officials carry a whistle and a weighted, bright yellow flag, which they throw to signal that a penalty has been called on a particular play. In the event that an official throws his yellow flag during a play and then sees yet another penalty, he throws his hat.

Officials are part-time workers for NFL, college, and high school football. They’re paid for working the game and are given travel expenses. In the NFL and in college football, the work can be financially rewarding. For instance, depending on seniority and experience, these officials may earn between $25,000 and $80,000 a season. High school officials, on the other hand, aren’t paid nearly as well; they generally do it for the love of the game.

If you want, you can just call them “the officials,” or — if you’re in a particularly belligerent mood — you can call them “the idiots who aren’t even qualified to officiate a peewee football game.” Either way, true diehards know that each of the seven officials (five or six at some levels) has a different title and task. The sections that follow explain who they are and what they do.

Referee

The referee has general oversight and control of the game. He’s the final authority for the score, the number of a down in case of a disagreement, and all rule interpretations when a debate arises among the other officials. He’s the only official who wears a white hat; all the other officials wear black hats.

The referee announces all penalties and confers with the offending team’s captain, explaining the penalty. Before the snap of the ball, he positions himself in the offensive backfield, 10 to 12 yards behind the line of scrimmage, and favors the right side if the quarterback is right-handed or the left side if the quarterback is left-handed. The referee also monitors any illegal hits on the quarterback, such as roughing the passer (you can read more about this penalty in Chapter 5). He follows the quarterback throughout the game and watches for the legality of blocks made near him.

At the end of any down, the referee can request the head linesman (see the later related section for details on this official’s role) and his assistants to bring the yardage chains onto the field to determine whether the ball has reached the necessary line for a new first down. The referee also notifies the head coach when any player is ejected for unnecessary roughness or unsportsmanlike conduct.

Umpire

The umpire is responsible for the legality of the players’ equipment and for watching all play along the line of scrimmage, the division line between the offensive and defensive players. He makes sure that the offensive team has no more than 11 players on the field prior to the snap of the ball. At the start of a play in college football, he positions himself 4 to 5 yards off the line of scrimmage on the defensive side of the ball. In the NFL, he’s positioned in the offensive backfield until the final five minutes of each half, when he takes his traditional position on the defensive side.

Because he’s responsible for monitoring the legality of all contact between the offensive and defensive linemen, this official calls most of the holding penalties. He also assists the referee on decisions involving possession of the ball in close proximity to the line of scrimmage. He records all timeouts, the winner of the coin toss, and all scores, and he makes sure the offensive linemen don’t move downfield illegally on pass plays. Finally, when it’s raining, the umpire dries the wet ball prior to the snap.

Head linesman

The head linesman sets up on the side of the field designated by the referee. He straddles the line of scrimmage and watches for encroachment, offside, illegal men downfield, and all the other line-of-scrimmage violations (which you can read more about in the later “Penalties and Other Violations” section). He’s also responsible for ruling on all out-of-bounds plays to his side of the field.

The chain crew (described earlier in this chapter) is the responsibility of the head linesman. He grabs the chain when measuring for a first down. He’s usually the official who runs in after a play is whistled dead and places his foot to show where forward progress was made by the ball carrier at the end of the play. He assists the line judge (who stands opposite the head linesman) with illegal motion calls and any illegal shifts or movement by running backs and receivers to his side. Also, during kicks or passes, he checks for illegal use of hands, and he must know who the eligible receivers are prior to every play.

Line judge

The line judge lines up on the opposite side of the field from the head linesman and serves as an overall helper while being responsible for illegal motion and illegal shifts. He has a number of chores. He assists the head linesman with offside and encroachment calls. He helps the umpire with holding calls and watching for illegal use of hands on the end of the line, especially during kicks and pass plays. The line judge assists the referee with calls regarding false starts and forward laterals behind the line of scrimmage. He makes sure that the quarterback hasn’t crossed the line of scrimmage prior to throwing a forward pass. And if all that isn’t enough, he also supervises substitutions made by the team seated on his side of the field. On punts, he remains on the line of scrimmage to ensure none of the ends move downfield prior to the ball being kicked.

One of the line judge’s most important jobs is supervising the timing of the game. If the game clock becomes inoperative, he assumes the official timing on the field. He advises the referee when time has expired at the end of each quarter. In the NFL, the line judge signals the referee when two minutes remain in a half, stopping the clock for the two-minute warning. This stopping of the clock was devised to essentially give the team in possession of the ball another timeout. During halftime, the line judge notifies the home team’s head coach when five minutes remain before the start of the second half.

One of the line judge’s most important jobs is supervising the timing of the game. If the game clock becomes inoperative, he assumes the official timing on the field. He advises the referee when time has expired at the end of each quarter. In the NFL, the line judge signals the referee when two minutes remain in a half, stopping the clock for the two-minute warning. This stopping of the clock was devised to essentially give the team in possession of the ball another timeout. During halftime, the line judge notifies the home team’s head coach when five minutes remain before the start of the second half.

Back judge

The back judge has similar duties to the field judge (see the following section) and sets up 20 yards deep on the defensive side, usually to the tight end’s side of the field. He makes sure that the defensive team has no more than 11 players on the field and is responsible for all eligible receivers to his side.

After the receivers have cleared the line of scrimmage, the back judge concentrates on action in the area between the umpire and the field judge: It’s vital that he’s aware of any passes that are trapped by receivers. He makes decisions involving catching, recovery, or illegal touching of loose balls beyond the line of scrimmage. He rules on the legality of catches or pass interference, whether a receiver is interfered with, and whether a receiver has possession of the ball before going out of bounds.

After the receivers have cleared the line of scrimmage, the back judge concentrates on action in the area between the umpire and the field judge: It’s vital that he’s aware of any passes that are trapped by receivers. He makes decisions involving catching, recovery, or illegal touching of loose balls beyond the line of scrimmage. He rules on the legality of catches or pass interference, whether a receiver is interfered with, and whether a receiver has possession of the ball before going out of bounds.

The back judge calls clipping when it occurs on punt returns. (The upcoming “Recognizing 15-yard penalties” explains clipping and similar penalties.) During field goal and extra point attempts, the back judge and field judge stand under the goalpost and rule whether the kicks are good.

Field judge

The field judge lines up 20 yards downfield on the same side as the line judge. In the NFL, he’s responsible for the 40/25-second clock. (When a play ends, the team with the ball has 40 seconds in which to begin another play before it’s penalized for delay of game. If stoppage occurs due to a change of possession, a timeout, an injury, a measurement, or any unusual delay that interferes with the normal flow of play, a 25-second interval exists between plays.)

The field judge also counts the number of defensive players. He’s responsible for forward passes that cross the defensive goal line and any fumbled ball in his area. He also watches for pass interference, monitoring the tight end’s pass patterns, calling interference, and making decisions involving catching, recovery, out-of-bounds spots, or illegal touching of a fumbled ball after it crosses the line of scrimmage. He also watches for illegal use of hands by the offensive players, especially the ends and wide receivers, on defensive players to his side of the field.

Side judge

With teams passing the ball more often, the side judge was added in 1978 as the seventh official for NFL games. Some high school games are played without a side judge, but, like the NFL, college teams have adopted the use of the seventh judge. The side judge is essentially another back judge who positions himself 20 yards down field from the line of scrimmage and opposite the field judge. He’s another set of eyes monitoring the legalities downfield, especially during long pass attempts. On field goal and extra point attempts, he lines up next to the umpire under the goalpost and decides whether the kicks are good.

Familiarizing Yourself with Referee Signals

Because it’s awfully hard to yell loud enough for a stadium full of people to hear you, and because someone has to communicate with the timekeepers way up in the press box, the referee uses signals to inform everyone of penalties, play stoppages, touchdowns, and everything else that transpires on the field. Table 3-1 shows you what these signals look like and explains what they mean.

Table 3-1 Signaling Scoring Plays, Penalties, and Other Stoppages

|

Signal |

What It Means |

|

|

Clock doesn’t stop. The referee moves an arm clockwise in a full circle in front of himself to inform the offensive team that it has no timeouts, or that the ball is in play and that the timekeeper should keep the clock moving. |

|

|

Delay of game. The referee signals a delay of game by folding his arms in front of his chest. This signal also means that a team called a timeout when it had already used all its allocated timeouts. |

|

|

Encroachment. The referee places his hands on his hips to signal that an offside, encroachment, or neutral zone infraction occurred. |

|

|

Face mask. The referee gestures with his hand in front of his face and makes a downward pulling motion to signal that a player illegally grabbed the face mask of another player. |

|

|

False start/illegal formation. The referee rotates both forearms over and over in front of his body to signify a false start, an illegal formation, or that the kickoff or the kick following a safety is ruled out of bounds. |

|

|

First down. The referee points with his right arm at shoulder height toward the defensive team’s goal to indicate that the offensive team has gained enough yardage for a first down. |

|

|

Fourth down. The referee raises one arm above his head with his hand in a closed fist to show that the offense is facing fourth down. |

|

|

Holding. The referee signals a holding penalty by clenching his fist, grabbing the wrist of that hand with his other hand and pulling his arm down in front of his chest. |

|

|

Illegal contact. The referee extends his arm and an open hand forward to signal that illegal contact was made. |

|

|

Illegal crackback block. The referee strikes with an open right hand around the middle of his right thigh, preceded by a personal foul signal, to signal an illegal crackback block. |

|

|

Illegal cut block. From the side, the referee uses both hands to strike the front of his thighs to signal that a player made an illegal cut block. When he uses one hand to strike the front of his thigh, preceded by a personal foul signal, he means that an illegal block below the waist occurred. When he uses both hands to strike the sides of his thighs, preceded by a personal foul signal, he means that an illegal chop block occurred. When he uses one hand to strike the back of his calf, preceded by a personal foul signal, he means that an illegal clipping penalty occurred. |

|

|

Illegal forward pass. The referee puts one hand waist-high behind his back to signal an illegal forward pass. The referee then makes the loss of down signal. |

|

|

Illegal motion. The referee flattens out his hand and moves his arm to the side to show that the offensive team made an illegal motion at the snap or prior to the snap of the ball. |

|

|

Illegal push. The referee uses his hands in a pushing movement with his arms below his waist to show that someone on the offensive team pushed or illegally helped a ball carrier. |

|

|

Illegal shift. The referee uses both arms and hands in a horizontal arc in front of his body to signal that the offense used an illegal shift prior to the snap of the ball. |

|

|

Illegal substitution. The referee places both hands on top of his head to signal that a team made an illegal substitution or had too many men on the field on the preceding play. |

|

|

Illegal use of hands. The referee grabs one wrist and extends the open hand of that arm forward in front of his chest to signal illegal use of the hands, arms, or body. |

|

|

Illegally touched ball. The referee uses the fingertips of both hands and touches his shoulders to signal that the ball was illegally touched, kicked, or batted. |

|

|

Illegally touched pass. The referee is sideways and uses a diagonal motion of one hand across another to signal an illegal touch of a forward pass or a kicked ball from scrimmage. |

|

|

Incomplete pass. The referee shifts his arms in a horizontal fashion in front of his body to signal that the pass is incomplete, a penalty is declined, a play is over, or a field goal or extra point attempt is no good. |

|

|

Ineligible player downfield. The referee places his right hand on top of his head or cap to show that an ineligible receiver on a pass play was downfield early or that an ineligible member of the kicking team was downfield too early. |

|

|

Intentional grounding. The referee waves both his arms in a diagonal plane across his body to signal intentional grounding of a forward pass. This signal is followed by the loss of down signal. |

|

|

Interference. The referee, with open hands vertical to the ground, extends his arms forward from his shoulders to signify pass interference or interference of a fair catch of a punted ball. |

|

|

Invalid fair catch. The referee waves one hand above his head to signal an invalid fair catch of a kicked ball. |

|

|

Juggled pass. The referee gestures with his open hands in an up-and-down fashion in front of his body to show that the pass was juggled inbounds and caught out of bounds. This signal follows the incomplete pass signal. |

|

|

Loss of down. The referee places both hands behind his head to signal a loss of down. |

|

|

Player ejected. The referee clenches his fist with the thumb extended, a gesture also used in hitchhiking, to signal that a player has been ejected from the game. |

|

|

Personal foul. The referee raises his arms above his head and strikes one wrist with the edge of his other hand to signify a personal foul. If the personal foul signal is followed by the referee swinging one of his legs in a kicking motion, it means roughing the kicker. If the signal is followed by the referee simulating a throwing motion, it means roughing the passer. If the signal is followed by the referee pretending to grab an imaginary face mask, it’s a major face mask penalty, which is worth 15 yards. |

|

|

Reset 25-second clock. The referee makes an open palm with his right hand and pumps that arm vertically into the air to instruct the timekeeper to reset the 25-second play clock. |

|

|

Reset 40-second clock. With the palms of both hands open, the referee pumps both arms vertically into the air to instruct the timekeeper to reset the 40-second play clock. |

|

|

Safety. The referee puts his palms together above his head to show that the defensive team scored a safety. |

|

|

Stop the clock. The referee raises one arm above his head with an open palm to signify that excessive crowd noise in the stadium has made it necessary for the timekeeper to stop the clock. This signal also means that the ball is dead (the play is over) and that the neutral zone has been established along the line of scrimmage. |

|

|

Timeout. The referee signals a timeout by waving his arms and hands above his head. The same signal, followed by the referee placing one hand on top his head, means that it’s an official timeout, or a referee-called timeout. |

|

|

Touchback. The referee signals a touchback by waving his arms and hands above his head and then swinging one arm out from his side. |

|

|

Touchdown. The referee extends his arms straight above his head to signify that a touchdown was scored. He also uses this signal to tell the offensive team that it successfully converted a field goal, extra point, or two-point conversion. |

|

|

Tripping. The referee repeats the action of placing the right foot behind the heel of his left foot to signal a tripping penalty. |

|

|

Uncatchable pass. The referee holds the palm of his right hand parallel to the ground and moves it back and forth above his head to signal that a forward pass was uncatchable and that no penalty should be called. |

|

|

Unsportsmanlike conduct. The referee extends both arms to his sides with his palms down to signal an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty. |

Penalties and Other Violations

A penalty is an infraction of the rules. Without rules, a football game would devolve into total chaos because the game is so physically demanding and the collisions are so intense. A dirty deed or a simple mistake (like a player moving across the line of scrimmage prior to the ball being snapped) is a penalty. Football has more than 100 kinds of penalties or rule violations. Don’t worry, though. The next sections get you acquainted with several of them.

The specific penalties and their ramifications can get pretty complicated. You may want to read through Parts II and III to get a handle on the offense and defense first if you’re a beginner and really want to understand this stuff. If you have trouble with a particular term, turn to the Appendix. By the way, I describe how these penalties are called and enforced in the NFL. Some of these penalties are slightly different in the college ranks.

The specific penalties and their ramifications can get pretty complicated. You may want to read through Parts II and III to get a handle on the offense and defense first if you’re a beginner and really want to understand this stuff. If you have trouble with a particular term, turn to the Appendix. By the way, I describe how these penalties are called and enforced in the NFL. Some of these penalties are slightly different in the college ranks.

Looking at 5-yard penalties

The following common penalties give the offended team an additional 5 yards. Some of these penalties, when noted, are accompanied by an automatic first down.

· Defensive holding or illegal use of the hands: When a defensive player tackles or holds an offensive player other than the ball carrier. Otherwise, the defensive player may use his hands, arms, or body only to protect himself from an opponent trying to block him in an attempt to reach a ball carrier. This penalty also includes an automatic first down.

· Delay of game: When the offense fails to snap the ball within the required 40 or 25 seconds, depending on the clock. The referee can call a delay of game penalty against the defense if it repeatedly charges into the neutral zone prior to the snap; when called on the defense, a delay of game penalty gives the offense an automatic first down. The ref can also call this penalty when a team fails to play when ordered (because, for example, the players are unsure of the play called in the huddle), a runner repeatedly attempts to advance the ball after his forward progress is stopped, or a team takes too much time assembling after a timeout.

· Delay of kickoff: Failure of the kicking team to kick the ball after being ordered to do so by the referee.

· Encroachment: When a player enters the neutral zone and makes contact with an opponent before the ball is snapped.

· Excessive crowd noise: When the quarterback informs the referee that the offense can’t hear his signals because of crowd noise. If the referee deems it reasonable to conclude that the quarterback is right, he signals a referee’s timeout and asks the defensive captain to use his best influence to quiet the crowd. If the noise persists, the referee uses his wireless microphone to inform the crowd that continued noise will result in either the loss of an existing timeout or, if the defensive team has no timeouts remaining, a 5-yard penalty.

· Excessive timeouts: When a team calls for a timeout after it has already used its three timeouts allotted for the half.

· Failure to pause for one second after the shift or huddle: When any offensive player doesn’t pause for at least one second after going into a set position. The offensive team also is penalized when it’s operating from a no-huddle offense and immediately snaps the ball without waiting a full second after assuming an offensive set.

· Failure to report change of eligibility: When a player fails to inform an official that he has entered the game and will be aligned at a position he normally doesn’t play, like an offensive tackle lined up as a tight end. In the NFL, all players’ jersey numbers relate to the offensive positions they play; consequently, the officials and opposing team know when it’s illegal for a player wearing number 60 through 79 (offensive linemen generally wear these numbers) to catch a pass.

· False start: When an interior lineman of the offensive team takes or simulates a three-point stance and then moves prior to the snap of the ball. The official must blow his whistle immediately. A false start is also whistled when any offensive player makes a quick, abrupt movement prior to the snap of the ball.

· Forward pass is first touched by an eligible receiver who has gone out of bounds and returned: When an offensive player leaves the field of play (even if he’s shoved out), returns inbounds, and is therefore an ineligible receiver.

· Forward pass is thrown from behind the line of scrimmage after the ball crosses the line of scrimmage: When a player catches a pass, runs past the line of scrimmage, and then retreats behind the line of scrimmage and attempts another pass. However, a player is permitted to throw the ball to another player, provided that the ball isn’t thrown forward. A ball thrown this way is called a lateral.

· Forward pass touches or is caught by an ineligible receiver on or behind the line of scrimmage: When an offensive lineman catches a pass that isn’t first tipped by a defensive player.

· Grasping the face mask of the ball carrier or quarterback: When the face mask is grabbed unintentionally and the player immediately lets go of his hold, not twisting the ball carrier’s neck at all.

· Illegal formation: When the offense doesn’t have seven players on the line of scrimmage. Also, running backs and receivers who aren’t on the line of scrimmage must line up at least 1 yard off the line of scrimmage and no closer, or the formation is considered illegal.

· Illegal motion: When an offensive player, such as a quarterback, running back, or receiver, moves forward toward the line of scrimmage moments prior to the snap of the ball. Illegal motion is also called when a running back is on the line of scrimmage and then goes in motion prior to the snap. It’s a penalty because the running back wasn’t aligned in a backfield position.

· Illegal return: When a player returns to the field after he has been ejected. He must leave the bench area and go to the locker room within a reasonable time.

· Illegal substitution: When a player enters the field during a play. Players must enter only when the ball is dead. If a substituted player remains on the field at the snap of the ball, his team is slapped with an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty (see the later section “Recognizing 15-yard penalties” for more on this penalty). If the substituted player runs to the opposing team’s bench area in order to clear the field prior to the snap of the ball, his team incurs a delay of game penalty.

· Ineligible member(s) of kicking team going beyond the line of scrimmage before the ball is kicked: When a player other than the two players aligned at least 1 yard outside the end men go downfield when the ball is snapped to the kicker. All the other players must remain at the line of scrimmage until the ball is kicked.

· Ineligible player downfield during a pass down: When any offensive linemen are more than 2 yards beyond the line of scrimmage when a pass is thrown downfield.

· Invalid fair catch signal: When the receiver simply extends his arm straight up. To be a valid fair catch signal, the receiver must fully extend his arm and wave it from side to side.

· Kickoff goes out of bounds between the goal lines and isn’t touched: When the kicking team fails to keep its kick inbounds, the ball belongs to the receivers 30 yards from the spot of the kick or at the out-of-bounds spot unless the ball went out-of-bounds the first time an onside kick was attempted. In this case, the kicking team is penalized five yards and the ball must be kicked again.

· More than 11 players on the field at the snap: When a team has more than 11 players on the field at any time when the ball is live. The offense receives an automatic first down if the penalty is committed by the defensive team.

· More than one man in motion at the snap of the ball: When two offensive players are in motion simultaneously. Having two men in motion at the same time is illegal on all levels of football in the United States. Two players can go in motion prior to the snap of the ball, but before the second player moves, the first player must be set for a full second.

· Neutral zone infraction: When a defensive player moves beyond the neutral zone prior to the snap and continues unabated toward the quarterback or kicker even though no contact is made by a blocker. If a defensive player enters the neutral zone prior to the snap and causes an offensive player to react immediately and prior to the snap, the defensive player has committed a neutral zone infraction.

· Offside: When any part of a player’s body is beyond the line of scrimmage or free kick line when the ball is put into play.

· Player out of bounds at the snap: When one of the 11 players expected to be on the field runs onto the field of play after the ball is snapped.

· Running into the kicker or punter: When a defensive player makes contact with a kicker or punter. Note that a defender isn’t penalized for running into the kicker if the contact is incidental and occurs after he has touched the ball in flight. Nor is it a penalty if the kicker’s own motion causes the contact, or if the defender is blocked into the kicker, or if the kicker muffs the ball, retrieves it, and then kicks it.

· Shift: When an offensive player moves from one position on the field to another. After a team huddles, the offensive players must come to a stop and remain stationary for at least one second before going in motion. If an offensive player who didn’t huddle is in motion behind the line of scrimmage at the snap of the ball, it’s an illegal shift.

Surveying 10-yard penalties

These penalties cost the offending team 10 yards:

· Deliberately batting or punching a loose ball: When a player bats or punches a loose ball toward an opponent’s goal line, or in any direction if the loose ball is in either end zone. An offensive player can’t bat forward a ball in a player’s possession or a backward pass in flight. (The nearby sidebar titled “The Holy Roller” explains the genesis of this rule.)

· Deliberately kicking a loose ball: When a player kicks a loose ball in the field of play or tries to kick a ball from a player’s possession. The ball isn’t dead when an illegal kick is recovered, however.

· Helping the runner: When a member of the offensive team pushes or pulls a runner forward when the defense has already stopped his momentum.

· Holding, illegal use of the hands, arms, or body by the offense: When an offensive player uses his hands, arms, or other parts of his body to hold a defensive player from tackling the ball carrier. The penalty is most common when linemen are attempting to protect the quarterback from being sacked (tackled behind the line of scrimmage). The defense is also guilty of holding when it tackles or prevents an offensive player, other than the ball carrier, from moving downfield after the ball is snapped. On a punt, field goal attempt, or extra point try, the defense can’t grab or pull an offensive blocker in order to clear a path for a teammate to block the kick or punt attempt.

· Offensive pass interference: When a forward pass is thrown and an offensive player physically restricts or impedes a defender in a manner that’s visually evident and materially affects the opponent’s opportunity to gain position to catch the ball. This penalty usually occurs when a pass is badly underthrown and the intended receiver must come back to the ball and interfere rather than allow the defender to intercept the pass.

· Tripping a member of either team: When a player, usually close to the line of scrimmage, sees someone running past him and sticks out his leg or foot, tripping the player.

The Holy Roller

The rule that forbids offensive players from batting the ball forward came about after a controversial play that took place in a 1978 game between the Oakland Raiders and San Diego Chargers. Trailing the Chargers 20-14 with 10 seconds left in the game and desperately needing a touchdown to win, Raider quarterback Ken “The Snake” Stabler deliberately fumbled the ball forward at the Charger 14 yard line. The ball bounced to the 8-yard line, where Raider Pete Banaszak swatted the ball across the goal line. There, Raiders’ Hall of Fame tight end Dave Casper fell on the ball for a touchdown.

The controversial play became known as the “Holy Roller.” Said Oakland guard Gene Upshaw about the episode, “The play is in our playbook. It’s called ‘Win at Any Cost.’” Whatever you want to call the play, the NFL made it illegal to advance the ball by kicking or swatting it the following season.

Recognizing 15-yard penalties

These are the penalties that make coaches yell at their players because they cost the team 15 yards — the stiffest penalties (other than ejection or pass interference) in football:

· A tackler using his helmet to butt, spear, or ram an opponent: When a player uses the top and forehead of the helmet, plus the face mask, to unnecessarily butt, spear, or ram an opponent. The officials monitor particular situations, such as when a

· Passer is in the act of throwing or has just released a pass

· Receiver is catching or attempting to catch a pass

· Runner is already in the grasp of a tackler

· Kick returner or punt returner is attempting to field a kick in the air

· Player is on the ground at the end of a play

· A punter, placekicker, or holder simulates being roughed by a defensive player: When these players pretend to be hurt or injured or act like a defensive player caused them actual harm when the contact is considered incidental.

· Chop block: When an offensive player blocks a defensive player at the thigh or lower while another offensive player occupies that same defensive player by attempting to block him or even simulating a blocking attempt.

· Clipping below the waist: When a player throws his body across the back of the leg(s) of an opponent or charges, falls, or rolls into the back of an opponent below the waist after approaching him from behind, provided that the opponent isn’t a ball carrier or positioned close to the line of scrimmage. However, within 3 yards on either side of the line of scrimmage and within an area extended laterally to the original position of the offensive tackle, offensive linemen can block defensive linemen from behind.

· Delay of game at the start of either half: When the captains for either team fail to show up (or fail to show up in uniform) in the center of the field for the coin toss three minutes prior to the start of the game. A team whose captains fail to show loses the coin toss option and is penalized from the spot of the kickoff. The other team automatically gets the coin-toss choice.

· Face mask: When a tackler twists, turns, or pulls an opponent by the face mask. Because this move is particularly dangerous, the penalty is 15-yards and an automatic first down. If the referee considers his action flagrant, the player may be ejected from the game.

· Fair catch interference: When a player from the kicking team prevents the punt or kick returner from making a path to the ball or touching the ball prior to the ball hitting the ground. This penalty isn’t called when a kick fails to cross the line of scrimmage or a player making a fair catch makes no effort to actually catch the ball.

· Illegal crackback block by the offense: When an offensive player who lines up more than 2 yards laterally outside an offensive tackle, or a player who’s in a backfield position at the snap and then moves to a position more than 2 yards laterally outside the tackle, clips an opponent anywhere. Moreover, the offensive player may not contact an opponent below the waist if the blocker is moving toward the position from which the ball was snapped and the contact occurs within a 5-yard area on either side of the line of scrimmage.

· Illegal low block: When a player on the receiving team during a kickoff, safety kick, punt, field goal attempt, or extra point try blocks an opponent below the waist.

· Piling on: When a ball carrier is helpless or prostrate, defenders jump onto his body with excessive force with the possible intention of causing injury. Piling on also results in an automatic first down.

· Roughing the kicker: When a defensive player makes any contact with the kicker, provided the defensive player hasn’t touched the kicked ball before contact. Sometimes this penalty, which also results in an automatic first down, is committed by more than one defensive player as they attempt to block a kick or punt.

· Roughing the passer: When, after the quarterback has released the ball, a defensive player makes direct contact with the quarterback subsequent to the pass rusher’s first step after the quarterback releases the ball. The NFL wants to protect its star players, so this penalty is watched closely. Pass rushers are called for this penalty if they fail to avoid contact with the passer and continue to drive through or forcibly make contact with the passer. The defensive player is called for roughing if he commits intimidating acts such as picking up the passer and stuffing him into the ground, wrestling with him, or driving him down after he has released the ball. Also, the defender must not use his helmet or face mask to hit the passer. Finally, the defender must not strike the quarterback in the head or neck area or dive at his knees. Roughing the passer results in an automatic first down.

· Taking a running start to attempt to block a kick: When a defender takes a running start from beyond the line of scrimmage in an attempt to block a field goal or extra point and lands on players at the line of scrimmage. This penalty prevents defensive players from hurting unprotected players who are attempting to block for their kicker.

· Unnecessary roughness: This penalty has different variations:

· Striking an opponent above the knee with the foot, or striking any part of the leg below the knee with a whipping motion

· Tackling the ball carrier when he’s clearly out of bounds

· A member of the receiving team going out of bounds and contacting a player on the kicking team

· Diving or throwing one’s body on the ball carrier when he’s defenseless on the ground and is making no attempt to get up

· Throwing the ball carrier to the ground after the play is ruled dead (when an official has blown the whistle)

· Hitting a defenseless receiver in one of the following ways: leaving one’s feet and launching into the receiver or using any part of the helmet to initiate forceful contact

· Unsportsmanlike conduct: When a player commits any act contrary to the generally understood principles of sportsmanship, including the use of abusive, threatening, or insulting language or gestures to opponents, officials, or representatives of the league; the use of baiting or taunting acts or words that engender ill will between teams; and unnecessary contact with any game official.

Identifying specific pass-play penalties

These penalties occur only when the offensive team has attempted a forward pass. Here are three of the most common penalties you see on pass plays:

· Illegal contact: When a defensive player makes significant contact with a receiver who’s 5 yards beyond the line of scrimmage. Illegal contact is a 5-yard penalty and an automatic first down. This penalty has become much more prevalent in the NFL as the league no longer wants to see receivers impeded as they go out into their pass patterns.

· Intentional grounding: When a passer, facing an imminent loss of yardage due to pressure from the defense, throws a forward pass without a realistic chance of completing it. If he throws such a pass in his own end zone, a safety (two points) is awarded to the defense. It is not intentional grounding when a passer, while out of the pocket (the protected area within the area of two offensive tackles), throws a pass that lands at or beyond the line of scrimmage with an offensive player having a realistic chance of catching the ball. When out of the pocket, the passer is allowed to throw the ball out of bounds. The penalty is loss of down and 10 yards from the previous line of scrimmage if the passer is in the field of play, or loss of down at the spot of the foul if it occurs more than 10 yards behind the line.

· Pass interference: When a defensive player physically restricts or impedes a receiver in a visually evident manner and materially affects the receiver’s opportunity to gain position or retain his position to catch the ball. This penalty is an automatic first down, and the ball is placed at the spot of the foul. If interference occurs in the end zone, the offense gets a first down on the 1-yard line. However, when both players are competing for position to make a play on the ball, the defensive player has a right to attempt to intercept the ball.

Disputing a Call: The Instant Replay Challenge System

Under the instant replay challenge system, a coach who disagrees with a call can ask the referees to review it with instant replay. (The NFL resurrected this system in 1999 after trying and abandoning it in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and the NCAA has been using it since 2004.) Coaches can challenge up to two calls per game. However, if they challenge a call and the referees decide after reviewing it that the call stands, the team that issued the challenge loses a timeout. In the rare instance of a coach making two successful challenges within a game, he is allowed a third challenge.

To challenge a call, the coach must make the challenge before the ball is snapped and the next play begins. To signal a challenge, the coach throws a red flag onto the field of play. Usually, coaches wait for the replay to be reviewed in the coaches’ booth upstairs, or they view the play on the stadium’s big screen before issuing a challenge.

In the NFL, in the final two minutes of each half, neither coach may challenge a call. A replay official monitors all plays and signals down to the field to the referee if any play or call needs to be reviewed. In addition, in the NFL, all scoring plays and turnovers (fumbles and interceptions) are automatically reviewed by the replay official.

Supporters of instant replay challenges say that challenges make the game fairer. The speed of the modern game puts a real strain on a referee’s ability to make accurate calls. Instant replay challenges offer teams an opportunity to reverse the occasional bad call. Detractors say that instant replay challenges slow down the game and aren’t “instant” at all. As well as the usual interruptions for timeouts, clock stoppages, and penalties, instant replay challenges take away the very thing that fans love most about football — its speed and excitement.