Football For Dummies (2015)

Part IV

Meet the Rest of the Team

Visit www.dummies.com/extras/football for an article on one of the great teams of all time, the 1965-1967 Green Bay Packers.

Visit www.dummies.com/extras/football for an article on one of the great teams of all time, the 1965-1967 Green Bay Packers.

In this part …

· Examine the ins and outs of special teams play

· Understand what coaches and other team members do on a football team

Chapter 12

Special Teams, Masters of the Kicking Game

In This Chapter

![]() Taking a look at special teams and who’s on them

Taking a look at special teams and who’s on them

![]() Beginning each game with a kickoff and kickoff return

Beginning each game with a kickoff and kickoff return

![]() Making (and blocking) field goal and extra point attempts

Making (and blocking) field goal and extra point attempts

![]() Recognizing the importance of punting

Recognizing the importance of punting

As you probably know, every football game begins with a kickoff. More than 97 percent of the time, a team kicks an extra point after scoring a touchdown. And every time a team scores, the team must kick off again. These are just a few examples of what’s known as the kicking game. The proper name for the group of players who take care of these tasks is special teams.

Overall, this group of players is remarkable. A lot of effort, skill, and courage are involved in manning these positions. But you can play ten years in the NFL, be a tremendous special teams performer, and play in virtual anonymity. Kickers and some return men garner attention, but for the other players — the guys who cover kicks and punts and block for kickers — the job is often pretty thankless in the eyes of the public and the media (and even within the team). Special teams players generally are noticed only for doing a poor job — when a punt or field goal attempt is blocked or when the opposition returns a kickoff for a touchdown. After you read this chapter, however, you should have a much greater appreciation for these fine athletes and the important tasks they do.

Finding Out Who’s Who on Special Teams

The players who put their foot to the ball are the placekickers, punters, and field goal kickers. They’re all also known as specialists. On some teams, the punter handles kickoff duties, and the placekicker is responsible for field goal and extra point attempts. Other teams have players for all three positions. But there’s a lot more to the kicking game than these two or three players.

When a punter attempts a punt, for example, 21 other players are on the field. The ten remaining men on the punting team have two tough responsibilities: to protect the punter’s kick from being blocked and then to run down the field and cover the punt. They face ten players who are trying to slow them down, as well as the player who’s catching the punt (the punt returner). The returner is generally one of the fastest runners on a team and a specialist in his own right. The punting team wants to prevent the return man from gaining a single yard, whereas the punt returner obviously wants to go the distance and score a touchdown. At the very least, he wants to place his team’s offense in good field position, shortening the distance that the offense must travel to score.

Specialists have their own coach, known as a special teams coach, who serves in a capacity similar to that of an offensive or defensive coordinator in that he coaches a large group of players and not merely a specific position (flip to Chapter 13 for full insight into the coaching lineup). Some teams also have a kicking coach who coaches basically two players, the punter and the kicker.

Special teams are so specialized that a single group of players can’t cover every situation. Four special teams units exist:

· The group of players that handles punts, kickoffs, and punt returns

· The unit that handles field goal and extra point attempts

· The group that takes care of kickoff returns

· The unit that attempts to block field-goal and extra-point attempts

Generally, great special teams players are unusual. Travis Jervey, who played for the Atlanta Falcons, Green Bay Packers, and San Francisco 49ers, and was selected for the Pro Bowl, had a pet lion. Special teams players are often the wild and crazy guys on a team, too. When coverage men stop a returner in his tracks, for example, they’re usually as excited as offensive players scoring touchdowns.

My own special teams experiences

My own special teams experiences

I was a special teams player during my first two years in the NFL. Being a small-college player from Villanova, playing on special teams gave me the opportunity to work my way up through the ranks on the Raiders. The NFL is kind of like the Army in that you have to prove you belong.

I was on most of the special teams units. I covered punts and kickoffs, plus I was part of the unit that tried to block field goal and extra point attempts. Matt Millen and I were the two bulldozers on the kick-blocking team. We used to get down in a four-point stance (both hands and feet on the ground) and line up on either side of the center, who snaps the ball. Ted Hendricks, who was over 6 feet 7 inches tall and had the longest arms I’d ever seen, would stand right behind us. Millen and I would basically function as a snowplow and clear a path for Hendricks. Ted was in charge; he’d tell us where to line up and what to do, and I remember him blocking a number of kicks.

When I became an All-Pro player in my third year in the NFL, my defensive line coach wouldn’t allow me to play on special teams anymore because he didn’t want me getting hurt. That’s pretty much the philosophy in the NFL today. For example, quarterbacks used to be the holders for field goals and extra points, but it’s pretty rare to see any of them holding these days. They don’t want to hurt those pretty fingers!

Understanding What’s So Special about Special Teams

A key thing to know about special teams is that these 11-man units are typically on the field for about 20 percent of the plays in a football game. But coaches often say that special teams play amounts to one-third of a football game — by that, they mean its total impact on the game.

Take scoring, for example — how games were won and lost in the 2014 NFL regular season:

· Offenses scored 1,187 touchdowns and 28 two-point conversions for a total of 7,178 points. Remember, teams earn six points for a touchdown and two points for a two-point conversion.

· Special teams accounted for 829 field goals made and 1,222 extra points for a total of 3,709 points just from kicking. Plus teams scored 13 touchdowns on punt returns and 6 touchdowns on kickoff returns for an additional 114 points.

· Defenses scored 73 touchdowns on interception returns and fumble recoveries, which totals 438 points.

So while the offense does most of the scoring, as you would expect, special teams contribute a pretty big chunk of the total points. Another important function of the special teams unit is to maintain good field position and to keep the opposition in bad field position. The main objective of the kickoff, for example, is to pin the opponent as far away from its end zone, and thus a score, as possible. Kickoff coverage teams strive, though, to put the opponent 80 yards or more away from scoring.

Field position terminology

The main line of demarcation on a football field is the 50-yard line. The area on both sides of the 50 is known as midfield territory. A lot of football terms are defense-oriented. Consequently, when a commentator says, “The Chicago Bears are starting from their own 18,” it means that the ball is on the 18-yard line and that the opposition, should it recover the ball, is only 18 yards away from scoring a touchdown. The Bears may be on offense, but they should be mindful of the precarious offensive position they’re in. They want to move the ball away from their goal line, and probably in a conservative fashion (say, by running the ball rather than throwing risky passes that could be intercepted).

Placekicking

Placekicking, which is one half of the special teams’ duties, involves kickoffs, field goal attempts, and extra point attempts (an extra point is also known as a point after touchdown, or PAT). Unlike punting, which I describe later in this chapter, a kicker boots the ball from a particular spot on the field. You can read about the three types of kicks and the rules and objectives behind them in the next sections.

Kicking off

For fans, the opening kickoff is an exhilarating start to any game. They see the two-sided thrill of one team attempting to block the other, helping its returner run through, over, and past 11 fast-charging players of the kicking team. (Well, make that ten players. The kicker usually stands around the 50-yard line after kicking the ball, hoping he doesn’t have to make a tackle.) And the kicking team wants to make a statement by stopping the returner inside his own 20-yard line. This is the object on every level of football, from peewee to college to the NFL.

The following sections help you understand what happens during a kickoff, from the decision made at the coin toss to the rules regulating kickoffs in the NFL.

Deciding whether to kick or to receive

At the coin toss, when captains from both teams meet the referee in the center of the field, the captain who correctly calls the flip of the referee’s coin decides whether his team is to receive or to defend a particular goal. For example, if the captain says he wants to defend a certain end zone, the opponent automatically receives the ball. If the winning captain wants the ball, the opponent chooses which end of the field his team will kick from (and the goal it will defend). Except in bizarre weather conditions — when it’s snowing, raining, or extremely windy — most teams elect to receive the kickoff because they want the ball for their offense.

On some occasions, a team may allow its opponent to receive after winning the coin toss, meaning it defers its right to kick off because the head coach probably believes that his defensive unit is stronger than the opposition’s offense and wants to pin the offense deep in its own territory, force a turnover, or make it punt after three downs. Adverse weather conditions are also a factor because they may jeopardize the players’ ability to field the kick cleanly, and some kickers have difficulty achieving adequate distances against a strong wind. In these conditions, a team may opt to receive the ball at the end of the field where the weather has less of an effect.

Setting up for the kickoff

For kickoffs, NFL and college kickers are allowed to use a 1-inch tee to support the ball. High school kickers may use a 2-inch tee. The kicker can angle the ball in any way that he prefers while using the tee, but most kickers prefer to have the ball sit in the tee at a 75-degree angle rather than have it perpendicular to the ground. During some games, strong winds prevent the ball from remaining in the tee. In those instances, a teammate holds the ball steady for the kicker by placing his index finger on top of the ball and applying the necessary downward pressure to keep it steady.

The kickoff team generally lines up five players on either side of the kicker. These ten players line up in a straight line about 8 yards from where the ball is placed on the kicking tee. If the kicker is a soccer-style kicker (I describe this type of kicker in the later related sidebar), he lines up 7 yards back and off to one side (to the left if he’s a right-footed kicker, or vice versa). As the kicker strides forward to kick the ball, the ten players move forward in unison, hoping to be in full stride when the kicker makes contact with the ball.

The kickoff team generally lines up five players on either side of the kicker. These ten players line up in a straight line about 8 yards from where the ball is placed on the kicking tee. If the kicker is a soccer-style kicker (I describe this type of kicker in the later related sidebar), he lines up 7 yards back and off to one side (to the left if he’s a right-footed kicker, or vice versa). As the kicker strides forward to kick the ball, the ten players move forward in unison, hoping to be in full stride when the kicker makes contact with the ball.

In both the NFL and college football, teams kick off from the 35-yard line. But that wasn’t always the rule. In the NFL from 1994 to 2010, the kick off was moved back five yards to the 30-yard line. In college, kickoffs came from the 30 from 2007 to 2011.

So why was the kickoff moved up to the 35? The rules committees in both the NFL and college want to improve player safety. When the kickoff comes from the 35 yard line, most kickers place the ball deep in the opposite end zone. These deep kicks mean that the receiving team is less likely to attempt a return and instead accept a touchback. A touchback occurs when a receiving player possesses the ball in the end zone and takes a knee (known as downing the ball) or when the kicked ball is allowed to bounce past the end line. Touchbacks automatically give the offense the ball on its own 20-yard line.

When a kickoff isn’t deep in the end zone, the receiving team is more likely to attempt a return. If the ball carrier has great blocking and can avoid a few tackles, he might return the ball past the 20-yard line, and that makes for exciting football. Unfortunately, kickoffs feature 22 players running full speed at each other, resulting in dangerous collisions. To reduce injuries, the NFL and the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) now require kick off from the 35-yard line.

The move to the 35-yard line has definitely increased the number of touchbacks in the NFL. From 1994 to 2010, the touchback percentage from all kickoffs was around 11 percent. From 2011 to 2013, touchbacks increased to 45 percent.

Kicking the ball

When the referee blows his whistle, the kicker approaches the ball. His objective is to hit the ball squarely in the lower quarter in order to get the proper loft and distance. As soon as the kicker’s foot makes contact with the ball, his ten teammates are allowed to cross the line of scrimmage and run downfield to cover the kick — basically, to tackle the player who catches the ball and attempts to return it back toward the kicking team. The ideal kickoff travels about 70 yards and hangs in the air for over 4.5 seconds. Maximizing hang time (the length of time the football is in the air) is important because it enables players on the kicking team to run down the field and cover the kick, thus tackling the return man closer to his own end zone.

Again, the kicking team’s objective in a kickoff is to place the ball as close to its opponent’s end zone as possible. After all, it’s better for your opponent to have to travel 99 yards to score a touchdown than it is for them to have to move the ball only, say, 60 yards. Plus, if you can keep the ball close to your opponent’s end zone, your defense has a better chance of scoring a touchdown if it recovers a fumble or intercepts an errant pass. And by pinning the opposition deep in its own territory and possibly forcing a punt, a team can expect to put its offense in better field position when it receives a punt.

To keep the kick returner from making many return yards, kickers may attempt to kick the ball to a specific side of the field (known as directional kicking) to force the return man to field the kick. The basis of this strategy is the belief that your kick coverage team is stronger than your opponent’s kick return unit and that the return man isn’t very effective. In this situation, the returner is often restricted, and the defense can pin him against the sidelines and force him out of bounds.

Many teams now opt to force the receivers into a touchback by either kicking the ball to deep into the end zone or out of the end zone completely. This tactic minimizes the risk of a long return. The offense then takes the ball at the 20-yard line.

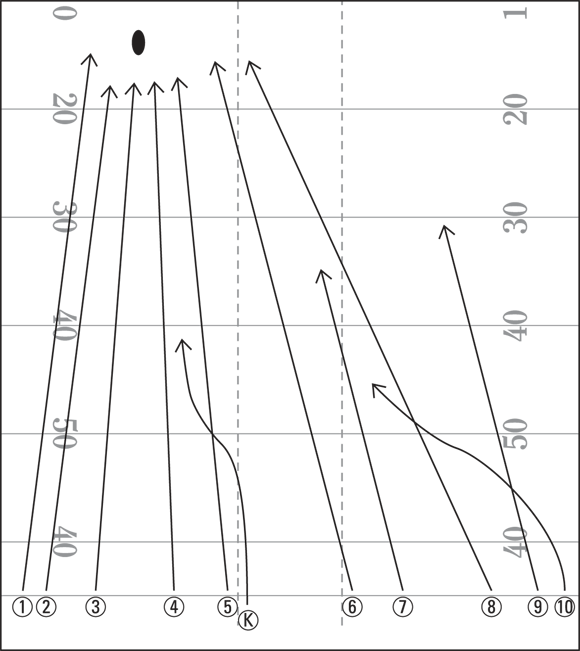

The kickoff formation shown in Figure 12-1 typifies directional kicking. Instead of simply kicking the ball straight down the middle of the field, the kicker angles the ball to the left side. This style is ideal against a team that lines up with only one kick returner. The directional kick forces the returner to move laterally and take his eyes off the ball. The kicking team’s purpose is to focus its coverage to one side of the field, where it hopes to have more tacklers than the return team has blockers.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 12-1: Kicking the ball to a specific side of the field forces the returner to field it and allows the kicking team to focus its coverage on that side of the field.

Following the rules of the kickoff

Like virtually everything else in football, kickoffs are strictly governed by a set of rules:

· The receiving team must line up a minimum of 10 yards from where the ball is kicked.

· Members of the kicking team can recover the ball after the kick travels 10 yards or the ball touches an opponent. If the kicked ball goes out of bounds before traveling 10 yards, the kicking team is penalized 5 yards and must kick again. If a member of the kicking team touches the ball before it travels 10 yards, the kicking team must kick again and is again penalized 5 yards.

· A member of the kicking team can recover the ball in the end zone and be awarded a touchdown.

· Members of the kicking team must give the receiving team’s returner the opportunity for a fair catch. If he signals for a fair catch, the players can’t touch him and can’t come within 3 feet of him until he touches the ball.

· The receiving team gets the ball on its own 40-yard line (25 yards from the spot where the ball was kicked) if the kickoff goes out of bounds before reaching the end zone. If it bounces out before the 40-yard line, the receiving team receives the ball where it went out of bounds.

The wackiest kickoff ever

The wackiest kickoff ever

Alumni and fans of the Stanford/University of California at Berkeley rivalry know it simply as “The Play.” It’s also the only known touchdown scored while running through the opposition’s band — as in marching band.

Stanford and UC Berkeley have faced each other in more than 110 games, and The Play occurred in the 85th meeting, on November 20, 1982. Stanford was ahead 20-19 with four seconds remaining, and most of the 75,662 fans were heading for the exits in Cal’s Memorial Stadium when Stanford’s Mark Harmon kicked off from his own 25-yard line because his team had been assessed a 15-yard penalty for excessive celebration following its go-ahead field goal. Given the field position and in an attempt to prevent a runback, Harmon made a percentage kick — a low-bouncing squibber. Such kicks are usually difficult to field and, because the ball isn’t kicked a great distance, allow the coverage team a shorter distance in which to tackle the opposition. At the time of the kick, the Stanford band, a legendary group known for its zany attire and performances, poured onto the south end of the field (Cal’s end zone), believing the game was over.

What happened next goes into football history under the “pretty unbelievable” category. Cal’s Kevin Moen caught the bouncing ball on his own 46-yard line and ran forward 10 yards, where he was surrounded by Stanford tacklers. But before he was downed, Moen lateralled to Richard Rodgers. (A lateral is a legal play in which the ball is passed or tossed backward; it’s illegal to pass forward on any type of running play.) Rodgers kept the ball briefly before tossing it back to running back Dwight Garner, who carried the ball to the Stanford 48-yard line. Garner was being tackled when he flipped the ball back to Rodgers, who started running forward again and, before he was tackled, lateralled to Mariet Ford, who sidestepped two tacklers and rushed to the Stanford 25-yard line.

As Ford was being tackled and falling to the ground, he tossed the ball up in the air, and backward, to Moen, the player who had originally fielded Harmon’s kickoff. By this time, Moen and the players who remained were running through the Stanford band. Moen sidestepped some band members and then smashed through the Stanford trombone player to score the winning touchdown.

Final score: Cal 25, Stanford 20.

Returning the kickoff

The ultimate purpose of a kickoff return is to score or advance the ball as close to midfield (or beyond it) as possible. A team’s ability to start out on offense in better-than-average field position greatly increases its chances for success.

Kickoff returners don’t usually figure greatly in a team’s success, but during the 1996 season, Desmond Howard was a major reason that the Green Bay Packers were Super Bowl champions. Howard returned only one kickoff for a touchdown that season, but his long returns always supplied tremendous positive momentum swings for his team. When he didn’t go all the way, Howard was adept at giving his team excellent field position. Anytime he advanced the ball to his own 30-yard line or beyond, he put his offensive teammates in better field position and, obviously, closer to the opponent’s end zone and a score.

Great kickoff returners possess the innate ability to sense where the tackling pursuit is coming from, and they can move quickly away from it. A great returner follows his initial blocks and, after that, relies on his open-field running ability or simply runs as fast as he can through the first opening. Both Gayle Sayers of the Chicago Bears and Terry Metcalf of the former St. Louis Cardinals were excellent at changing directions, stopping and going, and giving tacklers a small target by twisting their bodies sideways.

Teams want their kick returners to be able to run a 4.3-second 40-yard dash, but they also want them to have enough body control to be able to use that speed properly. Being the fastest man doesn’t always work because there’s rarely a free lane in which to run. Usually, somebody is in position to tackle the kickoff returner. Great returners cause a few of these potential tacklers to miss them in the open field.

The sections that follow offer insight into what happens when the ball lands in the returner’s hands, both from the offensive and defensive perspective, and present the kickoff return rules to know.

Understanding the kickoff return rules

The following rules govern the kickoff return:

· No member of the receiving team can cross the 45-yard line until the ball is kicked.

· Blockers can’t block opponents below the waist or in the back.

· If the momentum of the kick takes the receiver into the end zone, he doesn’t have to run the ball out. Instead, he can down the ball in the end zone for a touchback, in which case his team takes it at the 20-yard line.

· If the receiver catches the ball in the field of play and retreats into the end zone, he must bring the ball out of the end zone. If he’s tackled in the end zone, the kicking team records a safety and scores two points.

Before 2009, good return teams set up a blocking wedge with three or more huge players aligned together to clear a path for the ball carrier behind them. But in 2009, in the interest of player safety, the NFL prohibited teams from using more than two players to form a wedge on kickoff returns. Why the rule change? When you create a wall of three huge blockers in front of the ball carrier, the kicking team naturally wants to break through that wall to make the tackle. So defenders on the kicking team would get a 50-yard head of steam and crash into the wedge. Players who did this were known as wedge busters, and they were celebrated for their toughness and courage. Unfortunately, wedge busters were constantly risking injury to themselves and the blockers they collided into. The NFL decided that using wedges and busting wedges were just too dangerous.

Covering the kickoff return

Coverage men (the guys whose job it is to tackle the kick returner) must be aggressive, fast, and reckless in their pursuit. They must avoid the blocks of the return team. Special teams coaches believe that a solid tackle on the opening kickoff can set the tone for a game, especially if the return man is stopped inside his own 20-yard line. But the job of the kickoff coverage man isn’t an easy one. Players get knocked down once, twice, and sometimes three times during their pursuit of the kickoff returner. Not for nothing is the coverage team sometimes called the “suicide squad.”

Hidden yardage

Jimmy Johnson, who coached the Dallas Cowboys and the Miami Dolphins, called positive return yards hidden yardage. For example, Johnson equated a 50-yard advantage in punt/kick return yards to five first downs. In some games, it may be extremely difficult for an offense to produce a lot of first downs, so return yardage is key.

Johnson reported that his teams won games while making only 12 first downs because they played great both defensively and on special teams. He believed that the team with the best field position throughout the game, attained by excellent punt and kick coverage, generally wins. Also, he believed that if you have a great punt and kick returner, opponents may elect to kick the ball out of bounds, thus giving your offense fine field position.

Kicking field goals and PATs

Most special teams scoring involves the placekicker or field goal kicker. During the 2009 NFL season, the 32 pro teams attempted 930 field goals and converted 756 of them, which is an 81 percent success rate. For the last 35 years, field goal kicking has played a pivotal, often decisive, role in the outcomes of NFL games. Kickers can become instant heroes by converting a last-second field goal to win a game.After an NFL offense has driven to within 30 yards of scoring a touchdown, the coaches know the team is definitely within easy field goal range. In the 2009 NFL season, field goal kickers converted 265 of 274 attempts inside 30 yards for an impressive 97 percent conversion rate. Between 30 and 39 yards, NFL kickers made 85 percent of their attempts. However, teams saw a significant drop-off beyond 39 yards. Kickers made only 216 of 363 attempts from 40 yards or longer for a completion rate of 60 percent. Despite the decline in accuracy, you can see that coaches were still willing to at least attempt to score three points, knowing that a missed field goal gives the defensive team the ball at the spot of the kick.

Reliable kickers can often claim a job for a decade or more because their ability to convert in the clutch is so essential. For example, Morton Andersen played 25 seasons in the NFL with six teams. He holds the record for most career field goals with 565.

The following sections explain the roles of the folks involved in field goal and extra point attempts, what makes a kick count, and the rules regarding both types of kicks.

Who does what

On field goal and extra point (PAT, which stands for point after touchdown) attempts, the kicker has a holder and a snapper. He also has a wall of nine blockers in front of him, including the snapper, who’s sometimes the offensive center. On many teams, the player who snaps the ball for punts also snaps for these kicks. The snap takes approximately 1.3 seconds to reach the holder, who kneels on his right knee about 7 yards behind the line of scrimmage. He catches the ball with his right hand and places the ball directly on the playing surface. (Placekicking tees are allowed in high school football but not in college and the NFL.) The holder then uses his left index finger to hold the ball in place.

The kicker’s leg action, the striking motion, takes about 1.5 milliseconds, and the ball is usually airborne about 2 seconds after being snapped.

It’s good!

For an extra point or a field goal try to be ruled good, the kicked ball must clear the crossbar (by going over it) and pass between (or directly above one of) the uprights of the goalpost (see Chapter 2 for the specs of the goalpost). Two officials, one on each side of the goalpost, stand by to visually judge whether points have been scored on the kick.

Most college and NFL teams expect to convert every extra point, considering that the ball is snapped from the 2- or 3-yard line. A field goal is a different matter, though, due to the distance involved.

The rules

A few rules pertain strictly to the kicking game. Most of them decide what happens when a kick is blocked or touched by the defensive team. Because three points are so valuable, special teams place a great emphasis on making a strong effort to block these kicks. The team kicking the ball works just as diligently to protect its kicker, making sure he has a chance to score.

The byproduct of these attempts often leads to the defensive team running into or roughing the kicker. This infraction occurs when a player hits the kicker’s body or leg while he’s in the act of kicking. A penalty is also enforced when a player knocks down the kicker immediately after he makes the kick. The rules are fairly strict because the kicker can’t defend himself while he’s concentrating on striking the ball. (Check out Chapter 3 for more on these and other penalties.)

Some of the other rules regarding field goals and extra points:

Some of the other rules regarding field goals and extra points:

· Either team can advance a blocked field goal recovered behind the line of scrimmage.

· A blocked field goal that crosses the line of scrimmage may be advanced only by the defense. If the ball is muffed or fumbled, however, it’s a free ball and either team can recover it.

· On a blocked PAT in an NFL game, the ball is immediately dead. Neither team is allowed to advance it. In college football, the defense can pick up the ball and return it to the kicking team’s end zone for a two-point score (if they’re lucky).

· The guards may lock legs with the snapper only. The right guard places his left foot inside the snapper’s right foot after both players assume a stance so that their legs cross, or lock. The left guard places his right foot on the opposite side of the center. By locking legs, the guards help stabilize the snapper from an all-out rush on his head and shoulders while he leans down over the ball. All other players on the line of scrimmage must have their feet outside the feet of the players next to them.

· The holder or kicker may not be roughed or run into during or after a kick. The penalty for running into the kicker is 5 yards; the penalty for roughing the kicker is 15 yards and an automatic first down.

However, roughing the holder or kicker is legal if the kick is blocked, the ball touches the ground during the snap, or the holder fumbles the ball before it’s kicked.

· On a missed field goal, the ball returns to the line of scrimmage if it rolls dead in the field of play, is touched by the receiving team, goes into the end zone, or hits the goalpost. The defensive team assumes possession at that time.

Drop-kicking: The lost art

Before the ball was made thinner and distinctly more oblong to assist passers, the plumped version was easily drop-kicked. Yes, players would simply drop the ball and kick it after it touched the ground. The action was perfectly timed.

The current rules still allow drop-kicking, but the ball’s tapered design stops most players from trying it. The last successful drop kick in the NFL occurred on January 1, 2006, when Doug Flutie of the New England Patriots drop-kicked an extra point in the final game of his career. Prior to Flutie’s drop-kick, no one in the NFL had succeeded in making a drop-kick since the 1941 championship game, when the Chicago Bears’ Ray “Scooter” McLean successfully drop-kicked a PAT.

In a 2010 Thanksgiving Day game, Dallas Cowboys’ punter Mat McBriar fumbled the snap from the center, and after the ball bounced a couple times on the grass, kicked the ball in what might be described as a drop kick. The referees, however, ruled that McBriar’s kick wasn’t a drop kick at all, but a fumble followed by an illegal kick. Nice try, Mat!

Blocking field goals and PATs

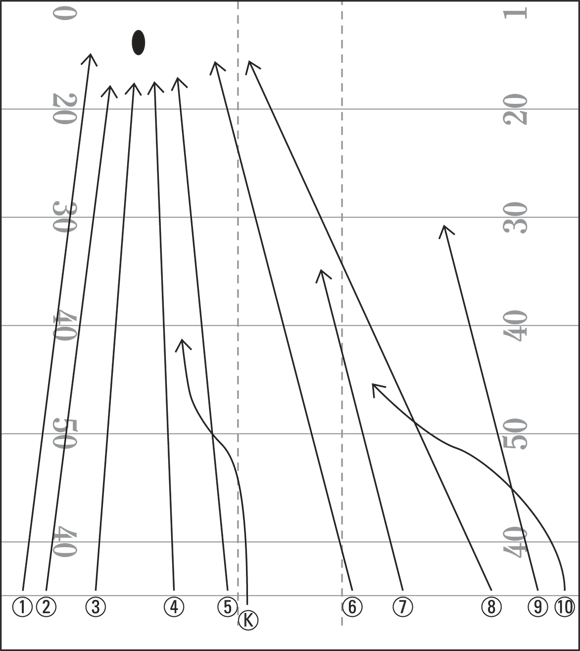

Blocking either a PAT or a field goal attempt can change the momentum of a game and eventually decide its outcome. To block kicks, players must be dedicated, athletic, and willing to physically sacrifice themselves for the good of the team, as the players in Figure 12-2 are doing. To have a successful block, each man must do his job.

Photo credit: © U.S. Navy/Getty Images

Figure 12-2: Navy defenders try to block a field goal attempt by Notre Dame’s D.J. Fitzpatrick in 2003.

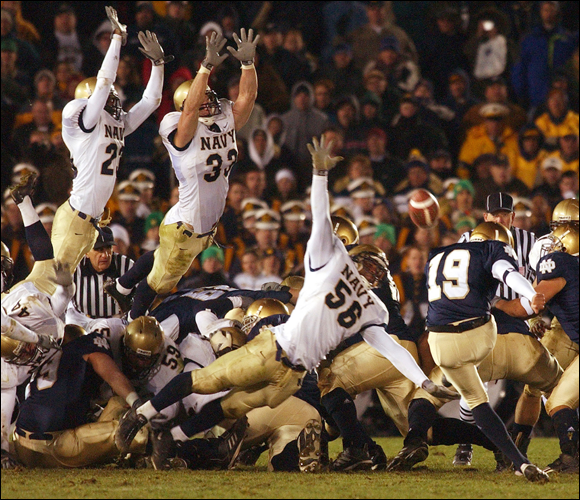

Blocked kicks may appear easy, but, as shown in Figure 12-3, a play such as the middle field goal block requires talented defensive linemen who can win the battle up front. These defensive linemen position themselves near the center snapping the ball because the quickest way to any field goal or extra point attempt is up the middle. With the ball 7 yards off the line of scrimmage, teams place their best pass-rushers in the middle, believing that one of them can penetrate the blocking line a couple of yards and then raise his arms, hoping to tip the booted ball with his hands. If the kicker doesn’t get the proper trajectory, the kick can be blocked.

Blocked kicks may appear easy, but, as shown in Figure 12-3, a play such as the middle field goal block requires talented defensive linemen who can win the battle up front. These defensive linemen position themselves near the center snapping the ball because the quickest way to any field goal or extra point attempt is up the middle. With the ball 7 yards off the line of scrimmage, teams place their best pass-rushers in the middle, believing that one of them can penetrate the blocking line a couple of yards and then raise his arms, hoping to tip the booted ball with his hands. If the kicker doesn’t get the proper trajectory, the kick can be blocked.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 12-3: The defensive linemen try to penetrate up the middle and block the kick.

In Figure 12-3, the three interior defensive linemen (LT, N, and RT) are over the two guards and the snapper. RT must align on the inside shoulder of the guard opposite him. N lines up directly across from the center. LT aligns on the inside shoulder of the guard opposite him. These linemen want to be able to gain an edge, an angle, on those blockers. Their attempts to block the kick won’t work if the two tackles align squarely on top of the guards. They must pick a particular shoulder of the guard and attack to that side.

Both LG and RG (left and right guard) drive through the tackles’ outside shoulders. Their objective is to apply enough individual pressure so as not to allow the tackle to slide down the line and help his buddies inside. Both players should attempt to block the kick if they break free. If not, they contain the opponent’s linemen in case of a fake field goal attempt. Containing means to hold their ground and simply jostle with the players who are blocking them — all while keeping their eyes on the kicker and holder.

The only chance the middle block has of succeeding is if the pass-rush moves that the three interior defensive linemen make on the offensive linemen work. It’s critical that all three players are isolated on one blocker. The defenders can decide to double-team a blocker, hoping one of them breaks free and penetrates the line.

The only chance the middle block has of succeeding is if the pass-rush moves that the three interior defensive linemen make on the offensive linemen work. It’s critical that all three players are isolated on one blocker. The defenders can decide to double-team a blocker, hoping one of them breaks free and penetrates the line.

On other kick-block plays, teams attempt to break through from the outside, using two men on one blocker and hoping the single blocker makes the wrong choice and allows the inside rusher to get free.

Soccer-style kicking

One of the biggest developments in kicking came in the late 1950s, when soccer-style kickers began surfacing at U.S. colleges. Before the soccer style came into vogue, the straight-on method was the only way to kick a football. This American style of kicking is totally different from the soccer style. Straight-on kickers approached the ball from straight on, using their toes to strike the ball and lift it off the ground. A soccer-style kicker, on the other hand, approaches the ball from an angle, and the instep of the kicker’s foot makes contact with the ball.

In 2010, not one NFL kicker used the straight-on method. For starters, the soccer style creates quicker lift off the ground. But basically, this method has simply stuck and become the pervasive kicking style. Mark Moseley, who retired from the Cleveland Browns in 1986, was the last straight-on kicker.

Punting

Punting occurs when a team’s offense is struggling, which means the offense is failing to generate positive yardage and is stuck on fourth down. Teams punt on fourth down when they’re in their own territory or are barely across midfield. By punting, the team relinquishes possession of the ball.

One of the most difficult aspects of football to understand initially is why teams punt the ball. A team has four downs to gain 10 yards, and after accomplishing that, it receives a new set of downs. Why not gamble on fourth down to gain the necessary yardage to maintain possession of the football? Field position is the answer. Unless it’s beyond the opponent’s 40-yard line, a team would rather punt the ball on fourth down, hoping to keep the opponent as far from its end zone as possible (which, of course, stops the other team from scoring).

One of the most difficult aspects of football to understand initially is why teams punt the ball. A team has four downs to gain 10 yards, and after accomplishing that, it receives a new set of downs. Why not gamble on fourth down to gain the necessary yardage to maintain possession of the football? Field position is the answer. Unless it’s beyond the opponent’s 40-yard line, a team would rather punt the ball on fourth down, hoping to keep the opponent as far from its end zone as possible (which, of course, stops the other team from scoring).

Teams punt routinely at the beginning of the game, especially when there’s no score or the score is close. They rely on their defenses in such situations, believing that the benefits of field position outweigh any offensive risk-taking. Punting in these situations isn’t a conservative tactic, but a smart one.

Punting is a critical part of football because some coaches believe it can change the course of a game. And no facet of the game alters field position more than punting. In the NFL, each punt is worth an average of 45 yards per exchange. However, some punters are capable of punting even farther than that, thus pinning opponents deep in their own end of the field and far, far away from a score.

Punting is a critical part of football because some coaches believe it can change the course of a game. And no facet of the game alters field position more than punting. In the NFL, each punt is worth an average of 45 yards per exchange. However, some punters are capable of punting even farther than that, thus pinning opponents deep in their own end of the field and far, far away from a score.

The sections that follow get you acquainted with the punting process, the members of the punting team, the rules regarding punting, and more.

Setting up and kicking the ball

The punter stands about 15 yards behind the line of scrimmage and catches the ball after the snapper hikes it. The center’s snap of the ball must reach the punter within 0.8 seconds. Every extra tenth of a second increases the risk that the punt may be blocked.

After receiving the ball, the punter takes two steps, drops the ball toward his kicking foot, and makes contact. This act requires a lot of practice and coordination because the velocity of the punter’s leg prior to striking the ball, as well as the impact of his foot on the ball, is critical. The punter needs to strike the ball in the center to achieve maximum distance. When the punter strikes the ball off the side of his foot, the ball flies sideways (such a mistake is called a shank).

A punt, from the snap of the ball to the action of the punter, requires no more than 2 seconds. Most teams want the punter to catch, drop, and punt the ball in under 1.3 seconds.

Today’s punters must be adept at kicking in all weather conditions and must strive for a hang time of 4.5 seconds. They must also boot the ball at least 45 yards away from the line of scrimmage. By the way, most punters also serve in a dual role as holder for the field goal kicker.

Meeting the key performers on the punt team

The punter isn’t the only important player during a punt play — although it may seem like it sometimes, especially on a bad punt. Following are some of the other key performers:

· Center or snapper: This player must be accurate with his snap and deliver the ball to where the punter wants it. On most teams, he makes the blocking calls for the interior linemen, making sure no one breaks through to block the punt.

· Wings: The wings are the players on both ends of the line of scrimmage, and they’re generally 1-yard deep behind the outside leg of the end or tackle. These players must block the outside rushers, but they worry more about any player breaking free inside of them.

· Ends: One end stands on each side of the line of scrimmage, and they’re isolated outside the wings at least 10 to 12 yards. On some teams, these players are called gunners. Their job is to run downfield and tackle the punt returner. Often, two players block each end at the line of scrimmage in hopes of giving the punt returner more time to advance the ball.

· Personal protector: The personal protector is the last line of protection for the punter. This player usually lines up 5 yards behind the line of scrimmage. If five or more defensive players line up to one side of the snapper, the personal protector shifts his attention to that side and makes sure no one breaks through to block the punt.

Most coaches prefer that a fullback or safety play this position because they want someone who’s mobile enough to quickly move into a blocking position. Regardless, the personal protector must be a player who can react quickly to impending trouble and make adjustment calls for the ends and wings.

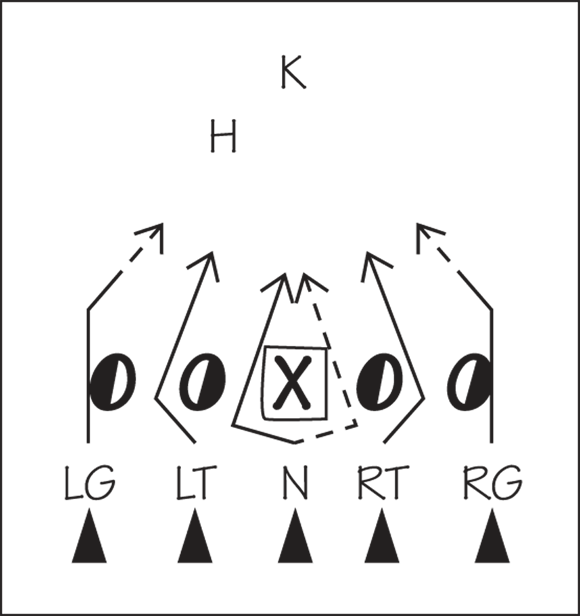

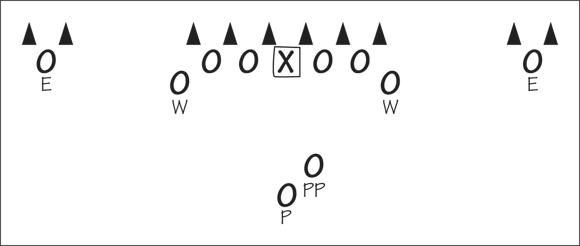

Figure 12-4 shows a basic punt formation involving these players against what coaches call man coverage. X is the center (or snapper); he stands over the ball. PP is the punter’s personal protector, and P is the punter. The wings are labeled with Ws, and the Es (ends) are on the line of scrimmage about 10 to 12 yards away from the wings.

© John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Figure 12-4: A basic punt formation.

Reviewing punt rules

As with everything else in football, punting has rules. Consider the following:

· In the pros, only the players lined up on the ends are permitted to cross the line of scrimmage after the ball is snapped to the punter and before the ball is punted. In college and high school, all players on the punting team may cross the line of scrimmage after the snap.

After the ball is punted, everyone on the punting team is allowed to cross the line of scrimmage with the intent of tackling the player fielding the punt (who’s also known as the punt returner).

· Players aren’t allowed to block below the waist on punt returns. Such an illegal block is a 15-yard penalty and is marked off from where the team returning the punt gained possession of the ball.

· If a punt doesn’t cross the line of scrimmage, either team may pick up the ball and run toward its own end zone.

· A touchback occurs when a punt touches the end zone before the ball touches a player on either team, or when the punt returner catches the ball in the end zone and drops to one knee. The ball is then spotted on the receiving team’s 20-yard line.

· Either team can down a punt after it hits the ground or after one of its players touches the ball past the line of scrimmage. To down the ball, a player must be in possession of the ball, stop his forward movement, and drop to one knee. Such action leads to an official blowing his whistle, signaling the end of action.

· A partially blocked punt that crosses the line of scrimmage is treated like a typical punt.

Several times during a game, you see the punt returner stand and simply catch the ball. He doesn’t run. In this case, he’s probably calling for a fair catch. To signal for a fair catch, the player who’s preparing to receive the punt must clearly extend his arm over his head and then wave it from side to side to let the officials and the defensive players know that he doesn’t plan to run with the ball after catching it. After signaling for a fair catch, the punt returner can’t advance the ball. If the defenders tackle him after he signals a fair catch, the kicking team incurs a 15-yard penalty.

Several times during a game, you see the punt returner stand and simply catch the ball. He doesn’t run. In this case, he’s probably calling for a fair catch. To signal for a fair catch, the player who’s preparing to receive the punt must clearly extend his arm over his head and then wave it from side to side to let the officials and the defensive players know that he doesn’t plan to run with the ball after catching it. After signaling for a fair catch, the punt returner can’t advance the ball. If the defenders tackle him after he signals a fair catch, the kicking team incurs a 15-yard penalty.

However, the player signaling for a fair catch isn’t obligated to catch the ball. His only worry is not to touch the ball because if he does so without catching it, the loose ball is treated like a fumble, and the other team can recover it. After he touches it or loses control and the ball hits the ground, either team is allowed to recover the ball.

If the returner muffs a kick, or fails to gain possession, the punting team may not advance the ball if they recover it. If the returner gains possession and then fumbles, however, the punting team may advance the ball.

Punting out of trouble

A punter must remain calm and cool when punting out of trouble — that is, anywhere deep in his own territory. Any poor punt — a shank or a flat-out miss — can result in the opponent scoring an easy touchdown, especially if the other team gets the ball 40 yards away from its end zone. Poor punts inevitably mean an automatic three points via a field goal. A dropped snap can mean a defensive score; ditto for a blocked punt — and you’ll see little sympathy when that punter returns to the sideline. In 2013, NFL teams averaged 4.9 punts per game, so coaches and players fully expect punts to happen without a hitch.

When I played with the Raiders in Super Bowl XVIII, our punter, Ray Guy, won the game for us. You may be thinking, “What role can a punter have when you beat the Washington Redskins 38-9?” Well, after a bad snap early in the game, Guy jumped as high as he could and grabbed the ball one-handed. When he landed, he boomed his punt way downfield. We were deep in our own territory, and if the ball had gone over Guy’s head, the Redskins might have recovered it in our end zone for a touchdown. Who knows?

When I played with the Raiders in Super Bowl XVIII, our punter, Ray Guy, won the game for us. You may be thinking, “What role can a punter have when you beat the Washington Redskins 38-9?” Well, after a bad snap early in the game, Guy jumped as high as he could and grabbed the ball one-handed. When he landed, he boomed his punt way downfield. We were deep in our own territory, and if the ball had gone over Guy’s head, the Redskins might have recovered it in our end zone for a touchdown. Who knows?

Guy was a fabulous athlete. He was a first-round draft choice (who ever heard of a punter being taken in the first round?) and a tremendous secondary performer at Southern Mississippi. All I remember about him was that he was like Cool Hand Luke, the role Paul Newman played in the 1967 movie of the same name. No matter the situation, even if he was punting from our own end zone, Guy never got frazzled. In all my years in the NFL, he was head and shoulders above every punter I saw. He was such an exceptional athlete that he served as the quarterback on the scout team in practices, but all he ever did for us in games was punt. Guy led the NFL in punting during three seasons and retired after 14 years with a 42.4-yard average.

The quick kick

One of the most underutilized trick plays in football is the quick kick. The quick kick is when the offensive team surprises the defense by punting the ball on third or even second down, usually from the shotgun formation (described in Chapter 5), although sometimes the ball is pitched to a halfback who does the punting. Teams try the quick kick when they’re deep in their own territory and want to get the heck out of there. A quick kick is a risky play because the kicker is closer to the line of scrimmage, which increases the chances of his kick being blocked, and most quarterbacks and halfbacks aren’t capable of punting the ball well. Still, if the play works, the ball can travel many yards because no defender is lined up deep in the defensive backfield to catch the punted ball.

Examining the dangerous art of punt returning

Punt returning isn’t always as exciting as returning a kickoff because the distance between the team punting and the punt returner isn’t as great. A punt returner needs either a line-drive punt or a long punt (45 yards or more from the line of scrimmage) with less than four seconds of hang time — or spectacular blocking by his teammates — to achieve significant positive return yards.

To produce positive return yards, the receiving team must concentrate on effectively blocking the outside pursuit men and the center — the players who have the most direct access to the punt returner. The rest of the unit must peel back and attempt to set up a wall or some interference for the returner. Whenever the return unit can hold up four or five players from the punting team, the returner has a chance.

To produce positive return yards, the receiving team must concentrate on effectively blocking the outside pursuit men and the center — the players who have the most direct access to the punt returner. The rest of the unit must peel back and attempt to set up a wall or some interference for the returner. Whenever the return unit can hold up four or five players from the punting team, the returner has a chance.

A returner needs to be a fearless competitor and must be willing to catch a punt at or near full speed and continue his run forward. If the defense isn’t blocked, the collisions between a returner and a tackler can be extremely violent, leading to injuries and concussions.

A returner’s other necessary qualities are superior hands and tremendous concentration. Because of the closeness of the coverage and the bodies flying around, the returner usually catches the ball in traffic. Several players are generally within a yard of him, so the sounds of players blocking and running tend to surround him. He must close out these sounds in order to catch the ball and maintain his composure. To catch the ball and then run with it, under such conditions, takes guts. A returner’s final fear is losing the ball via a fumble, thus putting his opponent in favorable field position.

Punt returns typically average around 8 or 9 yards. Great punt returners including Devin Hester and DeSean Jackson have seasons where they average more than 15 yards per return.

A special teams player who’s truly special

In 1986, the NFL and its players began awarding Pro Bowl invitations to each conference’s best special teams player. Mainly, the award winner is the player who’s best at covering punts and kickoffs — the one who’s a fearless open-field tackler. Steve Tasker of the Buffalo Bills was even named the MVP of the 1993 Pro Bowl for forcing a fumble and blocking a field goal attempt, thereby preserving a three-point victory for his AFC teammates.