Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

8

Windsor and Eton

‘Say, Father Thames, for thou hast seen

Full many a sprightly race

Disporting on thy margent green

The paths of pleasure trace’

Thomas Gray, ‘Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College’, 1747

Windsor and Eton have a unique place in the story of Thames swimming because, unlike other riverside towns, the tradition of bathing, among royalty and privileged Eton College boys, has been well documented here for hundreds of years. In 1303 the eighteen-year-old prince who would later become Edward II injured his Court fool, Robert Bussard, while playing ‘a trick’ on him in the Thames one winter’s day, and had to pay four shillings’ compensation. By the 1500s pupils at Eton, founded in 1440 by Henry VI, were bathing at numerous places along the river, while it was a group of Old Etonians who helped form an outdoor bathing group, said to be the first swimming society in England. Less well documented, however, is the swimming tradition among the townspeople, who were keen river users as well, with a public bathing place on the Thames as early as the 1850s, followed by local swimming clubs for both men and women.

The train from Waterloo to Windsor & Eton Riverside is busy with tourists; next to me a German woman and her daughter are consulting maps, while three Japanese visitors take snaps of the Thames from the window. They are presumably all on their way to the castle, the Queen’s official residence. The Thames is a short walk from the station and the water looks icy cold and grey; to my left is Windsor Bridge, to the right a large red DANGER sign in the middle of the river.

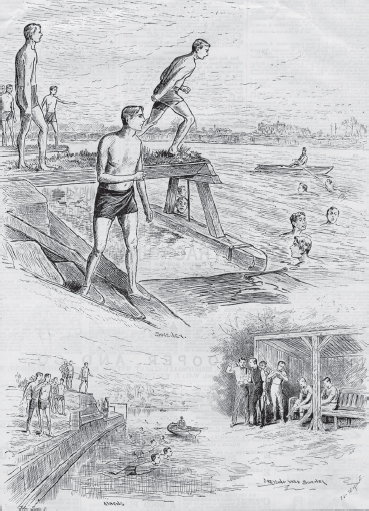

A newspaper illustration from the 1880s showing Eton boys at Athens and Boveney, two of the college’s swimming spots on the Thames. In theory bathing drawers were compulsory.

I reach the porter’s lodge at Eton College where I’m asked to sit in a chair to have my photograph taken. ‘Bit royal all of this,’ smiles the porter as he makes my ID card and I turn to stare at a picture of Princes William and Harry on the wall. I walk into the college grounds; the schoolyard is surrounded on all sides by ancient buildings, making it feel a bit like an exclusive barracks. There is, as Henry Skrine wrote in 1801, ‘an air of superior grandeur and propriety’ about the cobbled square, deserted today because it’s half-term. I head under an archway and through a small wooden door pitted with iron studs. My destination is the college archives, which has manuscripts dating back to 1091. I produce my passport and driving licence (getting into the archives is no easy matter) and the archivist, Penny Hatfield, lets me into a compact, book-lined room. I am the only person there but for an elderly man who appears to be studying cloth scrolls.

I sit down at the wooden table, carefully pulling my chair across the parquet floor. Tall windows let in the midday sun, providing a glimpse of blue sky, Gothic spires and a distant flagpole. All I can hear is the soft breathing of my companion who then tells me quietly that he’s researching fifteenth-century Fellows of Eton College. I open the first book Penny has laid out for me on the table, The Eton Book of the River, published in 1935. It’s a weighty tome with pages that have turned a pale yellow over the years, and while its focus is the evolution of boat racing there are two chapters on bathing. The first, ‘Bathing up to 1840’, is significantly subtitled ‘a chapter of accidents’.

Despite ‘the insanitary state of the river’, bathing took place at Eton ‘from a very early date’, with one boy drowning in 1549 after he’d gone to bathe from the playing fields. By the 1770s the college had hired ‘watermen’ with boats and one pupil, writing to his father in 1796, offered the following reassurance: ‘I hope you will not make yourself the least uneasy about my going into the water, as I do really assure you that I never go in without proper people attending.’ Another pupil remembered his swimming experiences a decade later: ‘Sooner or later all swam. Men were stationed at particular bathing places, to prevent accidents (to bathe elsewhere was a flogging), and they taught swimming at a guinea a head.’ But when he wrote to his father asking for the guinea, he ‘received an angry answer that in his time boys taught themselves to swim, and I might do the same’. It took him three days, ‘terrible work it was’, but this was followed by ‘great fun by land and water’. Some ‘little fellows’ had an unusual way of drying themselves, ‘catching a cow by the tail, using the towel for a whip, and making the animal gallop them about the meadow till they were dry’.

Within a few years the arrangements for bathing at Eton had been further improved. One pupil recollected, ‘those boys who are not able to swim are debarred from ablution except at particular places, where it is almost an utter impossibility from the shallowness of the water, that an accident can possibly occur’. Excellent swimmers appointed by the headmaster were ‘regularly paid by the boys’ to prevent mishap, and by now there were seven bathing places along the Thames: Sandy Hole, Cuckow Ware, Head Pile, Pope’s Hole, Cotton’s Hole, South Hope and Dickson’s Hole. ‘This use of the word Hole has died out in England,’ explains The Eton Book of the River, ‘but a bathing hole is still a common name for a bathing place in the United States; it has no derogatory sense such as it now suggests to us.’

Eton was also the centre for a number of swimming societies. In 1828 the Philolutic Society was formed, with members from Cambridge, Windsor and Eton. It was divided into two sections, the Philolutes and the Psychrolutes, ‘lovers of bathing and lovers of cold water’. The latter bathed outdoors daily between November and March, while members of both societies were called the Philopsychrolutes.

The Philolutic Society’s accounts book from 1829 to 1833 includes weekly fines for ‘non-bathing’ at a cost of two shillings and sixpence. The group’s treasurer and first president was the Right Honourable Sir Lancelot Shadwell; then nearly fifty, the former barrister and MP had been educated at Eton. In 1827 he’d become the last Vice-Chancellor of England and was knighted soon after. He was known to bathe every day, whatever the weather, in a creek of the Thames near Barn Elms where he once apparently granted an injunction during a swim. The society certainly had some prominent members; the list begins with Queen Victoria’s husband, HRH Prince Albert, HRH Prince George of Cambridge, the Earl of Denbigh and HRH the Duke of Cambridge. In total there are 183 members, some resident near Eton and others occasional visitors, but after a few pages it descends into pencil-scribbled surnames.

Next I pick up the 1828 Book of the Society of Psychrolutes, a large publication with pages set out like a ledger, and I turn them until I come to a chart listing ‘Rivers, Lakes and Streams bathed in by this Society’. The page is divided into columns, giving the name of the river or lake, which members bathed there and what, if any, were the remarks. First is the Thames, frequented by ‘most of the Club’ and ‘In all parts Superb!’ The Cam, ‘passable at Granchester but elsewhere, vile’, is also used by ‘all of the Society’. The Medway was ‘fair’, the Cherwell ‘Better than nothing’, the Wandle, ‘Cold. Insipid. Small’, and the Clyde ‘uncomfortable’. Members swam in rivers abroad as well, including the Seine and the Rhine. The book also features a full-page hand-drawn human skeleton with the caption, ‘This gentleman was Not a psychrolute’ and on the facing page, a rugged mountain of a man somewhat resembling a Roman soldier: ‘This gentleman was a psychrolute’.

In the following decades swimming for Eton pupils became even more organised, thanks to William Evans and George Selwyn who introduced classes under Evans’ tuition. Evans was drawing master, while Selwyn was a private tutor and a keen swimmer who would become Bishop of New Zealand. His feats included diving 10 feet over a thorn bush overhanging the river above Windsor, and while ‘going down in a sinking boat’ standing up on his seat and taking ‘a dexterous header before the boat disappeared’.

Until 1839 there had been ‘no systematic attempt to teach swimming’ at Eton, according to The Badminton Library, but that year a boy named Montagu drowned after being ‘dragged out of his boat by a barge rope’. As a result, Selwyn and Evans ‘prevailed’ upon the then headmaster, Dr Hawtrey, that all boys should pass an examination before they were allowed to go out in a boat. Just as would happen later at Oxford, the impetus for learning to swim at Eton came from the need to improve the safety of rowers.

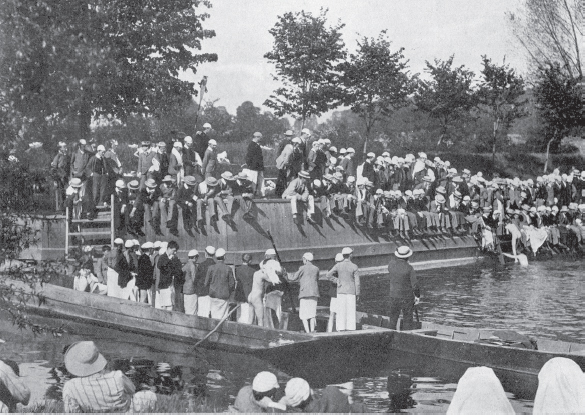

A ‘pass’ in progress at Eton, a regular summer event that included diving, swimming and treading water. In the 1890s around 200 boys passed each season.

The various tests, which became known as ‘passing’, or ‘the Eton pass’, included ‘a header’ (dive) from two or three feet above water, and a 100 yards swim, fifty with and fifty against a slow stream. Each boy also had to tread water and ‘while doing so, to keep his hands up to the level of his head or higher’, and to swim on his back. Only breaststroke was allowed, for the swimmer needed ‘a clear view all round him,’ explains The Eton Book of the River, ‘and this is in some circumstances essential for the avoidance of a blow on the head from the oar or scull of a passing coxswainless boat’.

Eton pupils became known as accomplished swimmers and the swimming school passing certificate from 1846 includes a quote from the eighteenth-century poet James Thomson, ‘This is the purest exercise of Health,/The kind refresher of the Summer heats’. The poet and novelist Algernon Charles Swinburne later wrote that his only ‘really and wholly delightful recollection’ of his time at Eton was ‘of the swimming lessons and play in the Thames’.

Over the years some of the old bathing places were abandoned, but Cuckow Ware - or Cuckoo Weir - and South Hope remained in use. In 1856 Evans was granted a land lease which stipulated he was to ‘permit and suffer the Masters and Schollars [sic] of Eton College to have free access through and over’ the land around Cuckoo Weir to the stream on the south side ‘for the purpose of bathing as heretofore accustomed’.

In 1860 Edmond Warre, an assistant master, took over from Evans and Selwyn, again improving Cuckoo Weir as well as two other swimming spots, Boveney and Athens. ‘Great credit is due to the authorities at Eton,’ wrote Henry Robertson in his 1875 book Life on the Upper Thames, where nearly every boy was a competent swimmer, ‘the result being that out of a school averaging eight hundred, not one case of drowning has occurred for many years; and this, at a place where everybody seeks the river as his natural out-of-doors home, makes Eton probably the first gymnasium for swimmers in the world.’

The next River Master was Walter Durnford, who reigned over the bathing places from 1885 to 1899, during which ‘trouble became rather acute with the Thames Conservancy owing to the objection of the innumerable Mrs. Grundies of those days to the sight of youth disporting itself naked and unashamed in the river and on the banks’. So bathing drawers were introduced and screens put up at Athens.

In the 1890s, ‘passing’ was held as soon as the water became warm enough, generally towards the end of May, at Cuckoo Weir. Much attention was paid to style, noted The Badminton Library, with the event repeated once or twice a week during the summer term, with 200 boys on average passing each season. The taking of ‘headers’ formed a characteristic feature of Eton swimming, with one ‘famous exponent of the art as a boy’ being the politician and cricketer Lord Harris, who was sent to Eton in 1864.

Once Edmond Warre left, a duumvirate was set up, the authors of The Eton Book of the River, L.S.R. Byrne and E.L. Churchill. Their first task was to try and restore ‘something approaching to the old proportion between the bathing accommodation and the number of boys in the school’. Cuckoo Weir had for years been used by Lower Boys and Non-nants (as non-swimmers were known), Athens by the 600-700 boys of the Fifth Form, while Boveney Weir stream was confined to a ‘select few’. It was then decided to widen Cuckoo Weir, which would later become known as Wards Mead Bathing Place.

The duumvirate ended shortly after the First World War, when Athens was bought for the college. Up to that point, the bathing spot had been rented from the Crown but in 1917 an Eton pupil, John Baker, was killed in a flying accident. The Commissioners for Crown Lands agreed to sell the land to his father, who gave it to the school in memory of his son, a ‘regular water baby’. Today there is still a stone tablet at Athens, opposite the Royal Windsor Race Course, in memory of young Baker, ‘a brilliant swimmer who spent here many of the happiest hours of his boyhood’. On one side of the stone is a sign outlining BATHING REGULATIONS AT ATHENS, as taken from the 1921 School Rules of the River. There was to be no bathing on Sundays after 8.30 a.m. and ‘boys who are undressed must either get at once into the water or get behind screens when boats containing ladies come in sight’. Boys were also not allowed to ‘land on the Windsor Bank or to swim out to launches and barges or to hang onto, or interfere with, boats of any kind’; anyone breaking the rule would be ‘severely punished’.

Swimming at Eton had certainly evolved over some 150 years, becoming safer, more skilled and far more regulated. Gone were the days of naked boys paying a guinea to learn how to swim; now pupils needed to obey rules restricting swimming to certain places at certain hours and to pass an exam, just as in other subjects.

By the 1920s Cuckoo Weir was used by other boys as well. A Pathé News clip shows ‘A Boys’ Camp at Cuckoo Weir’. It opens with camp leaders in pyjamas striding past a row of wigwam tents; they then burst into the tents, wake the boys, drag some of them out on their blankets, swing them by their hands and feet and toss them into the river. Later in the day there’s a swimming race, and after lunch the boys wash the dishes in the river.

By 1935 the Eton bathing spot at Boveney had been given up, although pupils still swam downstream from Boveney to Rafts, and the former ‘Masters’ Bathing Place’ at Romney Weir was used by both masters and the ‘more prominent boys in the school’. But the days of swimming in the Thames came to an end, at least officially, in the 1950s. Penny tells me this was partly because an outdoor pool was built, and also because of fears of pollution and polio. The highly infectious polio virus was a frequent cause of death and paralysis in the 1940s and 1950s, especially among children, who were warned to stay away from ponds and rivers.

I stack the old swimming society books into a neat pile and head back through Eton, stopping at an antique bookshop to ask the man behind the counter if he has any prints depicting bathing; he says someone came in the week before and bought them all. And would he ever swim in the Thames? He pulls a face: ‘I’ve seen the rats, and the current is really strong, especially around Windsor Bridge.’ He’s right; standing on the bridge a few minutes later I watch gulls floating speedily along like bath toys, the water rushing under the stone arches. Down on the Thames Path people are feeding the swans - throwing entire slices of bread - while others board a French Brothers’ boat. I walk along the path where the honking of geese is deafening, the landscape busy with bridges, a viaduct and various channels. There are plenty of signs: ‘river users’ are told to ‘take extreme care at all times’ particularly near the bridge, while danger signs warn of shallow water.

Under the viaduct bridge, and just before the modern Windsor Leisure Centre, is a sign to Baths Island & Pleasure Ground. A wooden bridge leads to the island, a wide stretch of grass deserted today but for a solitary man on a bike. It’s here that the town’s outdoor swimming baths were first built and on 1 May 1858 the press reported the opening of the Windsor Subscription Baths, ‘Season Tickets 8/-Gentlemen under 17 years of age 6/-. Great improvements have been made. An experienced Waterman with a punt will be in attendance and swimming taught. W.F. Taylor.’ Taylor had a shop opposite the parish church and was also known to run ‘peep shows’ of the Royal Apartments.

Then, in 1870, the baths were moved. ‘Queen Victoria was looking out of the castle windows one day and she saw all these half-naked men,’ explains long-time Windsor Swimming Club member Leslie Sturgess, ‘so it was moved to the other side of the railway bridge.’ The new site, between Jacobs Island and the riverbank, was known as Boddys Baths. It was home to the Windsor Swimming Club, founded in 1883, with a clubhouse on the island. There are earlier references to ‘the Windsor and Eton Swimming Club’, which had thirty-six members in 1881, but Leslie says this was a water polo club.

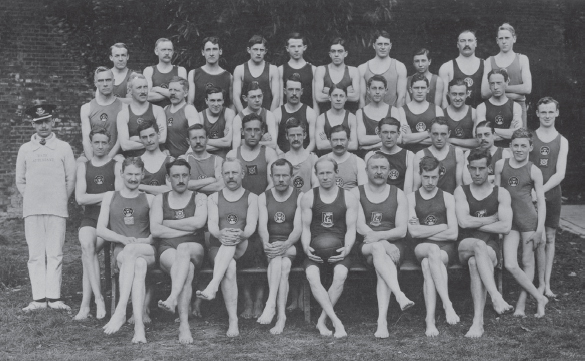

The Windsor Swimming Club, founded in 1883, held annual competitions which included Walking the Slippery Pole, with the winner receiving a butter dish.

The Windsor Club held annual competitions; with the winner of the 50 yards Novice Race being awarded a silver pencil case, and the winner of Walking the Slippery Pole receiving an ‘oak electro butter dish’. In July 1886 the press reported that the ‘first race for the championship of this rising Club came off in the river Thames early on Monday morning when, despite inclement weather a fair number of spectators assembled in the Eton Brocas to witness the event’. The course was from the Great Western Railway Bridge to the Swimming Baths, a distance of about 400 yards.

The club’s fourth annual competition included a 100 yards handicap final, a 50 yards handicap boys, running headers and Walking the Slippery Pole. This time there was a ‘numerous company of spectators present’ and Mayor Mr J. Lundy said he was ‘surprised and pleased to find ladies present’.

Sometime around 1896 the club was wound down, but was re-formed in 1909 at new baths built in 1904 and known as the Eastern Baths. This also appears to have been when a separate bath was created for women. In 1912 the Windsor Ladies Swimming Club was formed, one of many Thames-side clubs for women in the period. The press reported that within just a few months ‘its path has been paved with prosperity. The members have displayed the utmost enthusiasm, with the result the members have increased until at the present time it is a really healthy club doing an excellent work in the cultivation of the art of swimming.’ The year 1912 was a significant one for women: they were allowed for the first time to compete in Olympic swimming and diving events. Diving had become an Olympic sport for men in 1904, and swimming in 1908, but it was only at the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912 that women could take part and when Londoner Mary Belle White won bronze in the ten-metre platform event.

The object of the Windsor Club was ‘the encouragement of the art of swimming and life saving,’ explained its yearbook for 1923; fixtures included the mile, the half-mile and the 100 yards handicap, and any member found guilty of ‘regrettable behaviour’ would be expelled. While such behaviour isn’t defined, it may have had something to do with clothing, for the yearbook reminds members that at meetings of ‘both sexes’ and in all Amateur Swimming Association (ASA) championships competitors ‘must wear regulation bathing costumes and drawers’. By now there were numerous rules as to what women, and men, could wear while swimming at official events. The first ASA costume rule appeared in 1890, by which time costumes were being manufactured, but it applied only to men - the first ASA championships for women weren’t held until 1901. But already in 1899 rules on women’s costumes had been added; they were to have ‘a shaped arm, at least three inches long’ and the costume ‘shall be cut straight round the neck’. By the following year costumes could now only be black or dark blue, presumably because these were less transparent when wet. Men who didn’t wear the regulation costume when ‘ladies are present at Galas’ and who ‘swam without drawers’ were disqualified. Nine years later the rules were again revised, and now there was specific reference to ‘Ladies’ races in Public’. At competitions where ‘both sexes were admitted’ females over the age of fourteen had to wear ‘on leaving the dressing room, a long coat or bath gown before entering and immediately after leaving the water’, a rule that continued for decades. Women might now be competing publicly as amateurs and winning medals for Olympic diving, but social constraints meant they had to be appropriately dressed, the cut and length of their costume clearly defined, their bodies shielded from view until they got in the water and covered up again the moment they got out.

By 1930 things had changed somewhat and the Windsor Ladies’ life-saving competition now required competitors to swim 30 yards wearing clothes, ‘take off clothes in water. Dive for object 4ft, and bring same to bank on back.’ They also had to plunge in from the bank, save someone ‘by one release method and carry her 30 yards by one rescue method’. The women swam from Boveney Lock to Romney Lock, a distance of two miles and 572 yards, for which they received a lock-to-lock certificate.

Boys from Windsor Grammar School also took part in school swimming and diving sports at the public baths in the 1940s. By now mixed bathing had been introduced and diving boards installed, but the baths, like those at Reading, appear to have become derelict by the end of the war when they were full of rubbish. ‘Indoor pools were built around the area, at Slough and Maidenhead,’ explains Leslie Sturgess. ‘Our club had a hundred-year lease on the island but we were forced to close the clubhouse because of Health & Safety; the council said we had to do the place up and we couldn’t afford it.’

Windsor Swimming Club still exists, however, and its website explains that members have ‘achieved frequent success at County, Regional, National and International levels. Windsor has become one of the most admired clubs in the south of England, with a growing reputation.’ Their focus is ‘competitive development’, with training no longer held in the Thames but at various local indoor pools.

Human Race chose Windsor as the location for one of its annual swims, with the background of the iconic Windsor Castle.

But if swimming in the river at Eton and Windsor fell out of favour after the 1950s, today, as at Henley, Marlow and Maidenhead, it’s a popular place for mass-participation events. ‘Windsor is such an iconic centre,’ says John Lunt, founder of Human Race, ‘it has the castle and it’s great geographically and historically.’ When he launched the Windsor Triathlon in 1991, ‘we needed a place to swim; if there had been a lake in Windsor it would have been in a lake, but as the River Thames goes through the town it was perfect’. Places for the televised triathlon, named Event of the Year by the British Triathlon Foundation seven times, sell out in weeks.

Windsor has also been a memorable spot for those passing through the town after days submerged in the river. For Lewis Pugh arriving here in 2006, having swum from Lechlade, it was definitely a high point. ‘The Thames gradually descends; the source is only 110 metres above sea level and it has a long way to slowly descend across fields and meadows to the North Sea. It’s not like the Ganges, for example, which descends from high in the Himalayas and on either side there are valleys, glaciers and temples. I was struck by the sensory deprivation in the Thames, the water was mud-brown so I saw little underneath me and when I took a breath there was nothing except six foot of muddy banks on either side, that’s it … but then I hit Windsor and came round a bend in the river and saw the swans and there rising out of the mist was Windsor Castle! I told the Queen about that later, and her face lit up.’

Charlie Wittmack had a similar experience during his world triathlon in 2010: ‘when you swim your head is in the water, you can’t see anything all day, you can’t hear anything all day. All you’re left with is your thoughts and those thoughts can be really really tough, especially when the plan is to swim eighteen miles or more. There’s nothing to look at, listen to or smell all day long. One day I stopped and popped my head up out of the water and looked over and I was right outside of Windsor Castle! I hadn’t seen or heard anything all day and there it was, that was a fun surprise.’