Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

3

Oxford

‘The best time to bathe in the open air is early morning, for then the robust and healthy body has been strengthened by the night’s repose’

Charles Steedman, Manual of Swimming, 1867

Members of Oxford University’s 1936 water polo team dive in at Parson’s Pleasure on the River Cherwell, one of Oxford’s most famous swimming spots.

If ever there was a city famous for its enjoyment of river swimming it’s Oxford, from skinny dipping dons on the River Cherwell (a major tributary of the Thames), Victorian endurance swimmers on the Isis (as the Thames is locally known above Iffley Lock), to riverside family picnics and bathing in the 1960s. Yet while there were once several official swimming areas along the city’s waterways, most have been closed down since the 1990s, leaving only remnants behind.

The most famous, Parson’s Pleasure in the University Parks, was a male-only nude bathing spot on the Cherwell dating back to the seventeenth century. Women in passing punts were expected to get out at Parson’s Pleasure and walk, a tradition that continued into the 1970s. ‘I remember having to sink low in a punt, hat over face,’ recalls Heather Armitage, Tourism Officer at Visit Oxfordshire. ‘The men used to stand up at the riverside, gazing out, bits a-dangle. Ladies were supposed to get out of the punt and walk round the other side but no one did. You can still see the concrete blocks that formed the bases for diving boards.’ In 1934 women and children were given their own area on the Cherwell, with the opening of Dames’ Delight. But bathers had to wear costumes and pay an entrance fee, and after it was swept away in gales and floods in 1970 it was never repaired.

On the Thames there was Port Meadow, an area of ancient grazing land still used by swimmers, and Long Bridges, near Donnington Bridge, once the university bathing place. ‘A lady told me the elderly lifeguard was a friend at Long Bridges and he used to pour a kettle of hot water into the river to warm it up for her!’ says Heather. ‘It was a large bathing area, with walled banks, changing rooms and toilets. You can still see the shape of a pool in concrete.’ Tumbling Bay was another favoured spot, a pool between two weirs on a backwater of the Thames, which traces its history back to the nineteenth century.

It’s no wonder then that many adults in Oxford spent their childhoods immersed in local rivers. ‘Our mum used to take us for picnics by the Thames, and we swam from what seemed to us to be miniature beaches. As far as I was concerned, that was what rivers were there for!’ says Jenny Rogers, who was born in Oxford in 1952. ‘I mourn the passing of the River Bathing Places that gave us such simple pleasures for so many years, and helped us to grow up strong and fit.’

Oxford also has a long tradition of competitive river racing. The earliest recorded race appears to have been in the summer of 1840 when the National Swimming Society, formed three years earlier, offered silver medals as prizes for ‘swimming matches at Oxford’. The races were divided into five heats of four competitors, and the banks and towpath were thronged with up to 3,000 people. At 4 p.m. the starting gun was fired and the first men plunged in from a houseboat stationed at a bridge just beyond Iffley. The distance was 400 yards.

While the inhabitants of Oxford appear to have been far earlier participants in organised river racing than those at Lechlade, the impetus for learning to swim, at least among university students, was rowing, and early rowing almanacs suggest bathing was part of their training. The poet Robert Southey was said to have ‘learned two things only at Oxford, to row and to swim’. But as was the case upstream, many people died in the much-loved rivers; some drowned while bathing, others were carried over a sluice in a boat and some perished after recklessly leaping from a skiff at a weir. In 1859, after four undergraduates had died ‘in rapid succession’, Dr Acland, Regius Professor of Medicine, called a meeting of ‘boating men and others’. ‘Of course a great deal of nonsense was talked,’ reported one attendee, but it was agreed Oxford needed ‘a tepid swimming-bath’ and a rule that no one who ‘did not possess a swimming certificate should row in any University race’.

In 1870 the press reported on the ‘first’ Oxford swimming races, which took place on the ‘Isis between Harvey’s Barge and Iffley’, but spectators were ‘scanty’ and the race ‘seemed little known to the Undergraduate world’.

However, the following year the Penny Illustrated Paper was ‘glad to note that the Oxford University Boat Club has at last followed the example of Cambridge, and started some swimming races’. They took place between ‘the Gut’ (a bend or narrow passage in the river) and Iffley and included a half-mile race open to all university members, a distance diving race, a hurdle race and a 50-yard race open only to the ‘pupils of Harvey, the University water bailiff, an old and valued servant of the University’. In 1890 the Oxford University Boat Club agreed members had to have a certificate from the Merton Street Baths proving that they had swum ‘twice the length fully dressed’, the Oxford University Swimming Club was formed, and by the early 1920s there would be a women’s club as well.

An Oxford Regatta held during the First World War also included swimming. A Pathé News clip of the period opens with a row of boys diving off a long floating raft, then using an impressively fluid front crawl. Yet despite this tradition of river swimming there is very little in the way of documentation in any of the city’s museums or archives. Why is the history of Thames swimming so hard to find and why are documents so scarce? Why aren’t local museums full of evidence of how bathers once used the river? Perhaps, as local historian Mark Davies believes, ‘it was too commonplace to mention’.

But there is a rare Victorian book at the Old Bodleian Library, a manual of swimming written by Charles Steedman in 1867. A Londoner by birth, Steedman learned to swim at thirteen and six years later became a champion swimmer. He then emigrated to Australia in 1854, during the gold rush, where he continued his swimming career as champion of the state of Victoria. Steedman’s book is not the first of its kind; back in 1587 Everard Digby had written a treatise on swimming for Tudor gentlemen in Latin, De arte natandi, with woodcut illustrations. He argued that ‘man swimmeth by nature’ and set out when, where and how to swim, even including tips on cutting toenails while in the river. This was then translated into English by Christopher Middleton and a shortened version published in 1595, which now resides in the British Library. But Steedman’s manual is said to be the first text on competitive swimming and its emphasis is on what would today be called wild swimming. It was initially published in Melbourne but a later London edition gave it international renown and it’s often described as marking the beginning of swimming’s modern era.

It’s a dull spring day when I reach Oxford and I can barely move for people offering tours - walking tours, bus tours, ghost tours - the pavements before the grand sandstone buildings of the university packed with tourists. I head for the Bodleian Library on Broad Street, where I’m directed to the admissions building, closed today for a degree ceremony. Suddenly down the street comes a pack of graduates, black gowns and white scarves flapping in the breeze. I’m told to ask ‘one of the men in bowler hats’ to let me in, which he duly does, opening a pair of heavy black gates. Inside the office I watch a Canadian submit his forms, have his photograph taken and read out the Bodleian promise. He vows that he will not remove, mark, deface or injure any of the documents, he won’t ‘bring into the Library, or kindle therein, any fire or flame’ and neither will he smoke. The words are a translation of a traditional Latin oath, from the days when libraries weren’t heated because fires were so hazardous.

‘It’s bonkers today,’ says Sara Langdon, assistant admissions officer, as I’m finally shown to her desk. She goes through my forms, her face serious as she reads the section where I have to justify why I need to use the Bodleian and where I’ve explained I’m writing a book about Thames swimming. ‘How wonderful!’ she says, looking up from my form. ‘Swimming the Thames. It takes me back to my childhood.’ River swimming was something Sara took for granted while growing up in Oxford, and she has fond memories of swinging from trees and ropes and launching herself into the Isis. Why, she asks, hasn’t anyone written about this before?

‘I live in Wolvercote and last year I was crossing Port Meadow when I saw some young people, in their early teens, jumping off the bridge by the marina. It was a jolly hot day and I didn’t tell them off but I was quite concerned. I asked what they’d do if something went wrong and they said, “we do it all the time”. You can’t stop children, can you? But when I think of our mothers and how they let us swim in the Thames!’

I get my ID card and head back to the Bodleian, crossing the flagged courtyard as if about to enter a castle, heading for the lower reading room reserve on the first floor. There, at last, I get my hands on Steedman’s Manual of Swimming. After all this, it’s a disappointingly small book, just 270 pages. I was expecting a huge manual. I sit down at one of the reading desks; above the bookcases the white stone walls are hung with ancient portraits. The silence is broken only by the squeaking of shoes as someone walks past and the sound of my neighbour tapping away on her laptop.

I start leafing through the manual, looking at sections on bathing, plunging, diving, floating, scientific swimming, training, drowning and rescuing. Bathing has several subheadings including ‘Necessity of Cleansing the Skin, Pores, Perspiration, Virtue of cleanliness, Gouty persons’. The English, it seems, weren’t known for their cleanliness in Steedman’s day: ‘without exaggeration it may be safely asserted that the bodies of thousands have never been thoroughly washed.’

Swimming, he explains in capital letters, is THAT SPECIAL MODE OF PROGRESSION WHICH ENABLES A PERSON TO DERIVE ENTIRE SUPPORT FROM THE LIQUID IN WHICH HE IS IMMERSED. How complex this seems today, evidence that in Victorian times swimming was a new science, and a new art. It needed to be properly defined and would-be swimmers required plenty of advice. The best time to bathe in the open air was the early morning, for then the ‘robust and healthy body’ had been ‘strengthened by the night’s repose’ and benefited most from the shock of immersion. But it was ‘injurious’ to bathe on an empty stomach and Steedman advised, ‘take a cup of warm milk or coffee with a biscuit or a slice of stale bread before going into the water’. However, it also wasn’t a good idea to bathe on a full stomach.

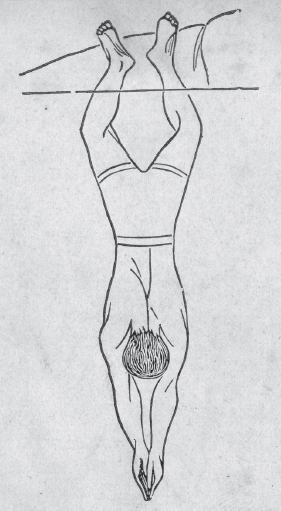

An illustration of the ‘vertical header’, part of a pack of swimming cards produced by a Professor H. Bocock in 1888. In Victorian times, swimming was a new science and a new art.

Steedman devotes much of his book to the subjects of drowning and rescuing, at a time when ‘more people have lost their lives’ because they couldn’t swim than from ‘any other one cause of accidental death’. In England and Wales ‘more than six persons’ drowned on a daily basis. While swimming was not as popular with the English as it was with the Prussians and French, Steedman assures his readers that this was not due to any physical inferiority, but because there were few good teachers and too many ‘amateur and defective ones’. This is presumably why he goes into great detail concerning proper leg and arm strokes, with accompanying diagrams. Cramp was a common affliction, but generally a minor one, and as far as Steedman is concerned made into more of a drama than necessary and unfairly blamed for several deaths.

Digestion and sweating are major concerns, however, and he gives plenty more tips on diet. Beef is most nutritious, but mutton is best thoroughly digested; underdone meat is better than overdone, and some swimmers, he notes, are partial to raw meat when training. It is all right to drink water, but no more than three pints a day; home-brewed ale is also acceptable as long as it is draught rather than bottled, and no more than a pint should be drunk. When training for a swim the ideal meal was an underdone steak or chop without fat, stale bread, a couple of mealy potatoes and greens.

Feeling hungry myself now, I leave the Bodleian in search of food as I make my way to the scene of a once famous endurance swim - undertaken by a man who may well have read Steedman’s manual. Fifteen minutes later I’m standing in the middle of Folly Bridge, looking down over the river. The water is green, spotted with silver glimmers of sunlight. Salter’s Steamers Boatyard, established in 1858, juts out into the river; a boat full of rowers appears in the distance. It was here that Lewis Carroll set out for Godstow (a hamlet on the Thames) with Alice Liddell and her sisters and, while journeying upriver, first came up with the story that would become Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. His 1865 book includes Alice’s swim with Mouse in the Pool of Tears, and illustrations variously show her doing a basic breaststroke or front crawl; but it’s unlikely the real Alice knew how to swim.

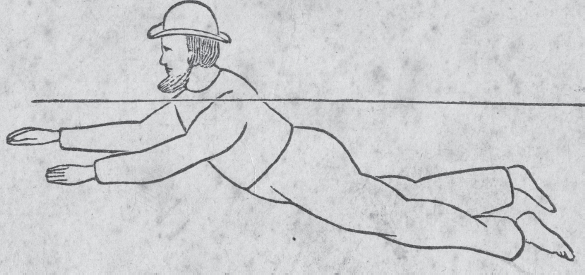

Professor Bocock explains how to swim fully clothed. Only ‘really advanced swimmers (could) swim in women’s garments on account of them wrapping around the feet’.

It was also here at Folly Bridge that in 1890 the honorary secretary of the ‘Professional Swimming Association’ (otherwise known as the National Swimming Association), Mr. T.C. Easton, attempted a six-day swim to Teddington. On 22 September he ‘commenced one of the most genuinely sportsmanlike performances ever attempted,’ reported the Morning Post admiringly. He would swim ninety-one miles to Teddington, covering eight hours a day, ‘and though the journey is a very favourite one for boating parties, the idea of accomplishing it by swimming does not seem to have previously occurred to any one’.

The American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne joined one such boating party near Oxford when he toured England in the 1860s, finding the river narrow, shallow and bordered with bulrushes and water-weeds, the shores flat and meadow-like and the water ‘clean and pure’. Boat trips from Folly Bridge to London were ‘very much the thing to do,’ explains Oxford historian Simon Wenham, ‘it was known as “the Thames trip”. Today the Boat House Tavern houses the drags for recovering bodies and the resuscitation apparatus. I’ve always wondered what the latter would have been in Victorian times.’

By then, Easton was already a well-known swimmer (in 1898 he came up with the idea of launching a professional long-distance championship from Kew to Putney) and he’d already made several attempts to swim from Richmond Bridge to London Bridge. In 1888, ‘owing to a very sluggish tide’, he’d only managed to get to Putney, but the following year he got as far as Westminster Bridge where he ‘seemed to become weak’ and left the water after completing fourteen miles in just over four hours. But he was back in the river again a few weeks later, this time covering twenty miles from London Bridge to Purfleet, and in 1890 he’d swum twenty miles from Blackwall to Gravesend. Now he’d turned his sights on Oxford and the press expected he would be ‘fully qualified to wrestle with his arduous task’, noting that he was thirty-seven, stood 5 feet 11 inches and weighed 16 stone.

At eight in the morning Easton entered the water at Folly Bridge and an hour later had reached Iffley Lock, a mile and a quarter downriver. ‘The weather was beautifully fine, although there was a strong adverse wind’ as, seven hours later, he reached Abingdon Lock and then stopped at Culham Lock after nine miles and five furlongs. Press coverage was substantial, with headlines such as EASTON’S LONG SWIM IN THE THAMES, though reports of the distances he covered each day varied. The Star reported a large assembly witnessed the start, and that Easton left the water ‘in a good condition’. Oxford already had a basic sewage system in place by the early nineteenth century, with the drains emptying into the Thames or its tributaries, but there were several serious cholera epidemics in the first half of the 1800s. A more efficient sewage system was put in place in the 1870s, though how clean the water was during Easton’s swim isn’t mentioned in the newspapers.

The following day he resumed swimming and ‘by means of a steady breaststroke’ continued until 10 a.m. ‘when a severe storm passed over’. However, he ‘persevered gallantly with his task’, according to the Daily News, and again stayed in the water for about eight hours. When he reached Shillingford Bridge, ‘Easton was in capital condition … and intends resuming his swim at eight o’clock this morning’. But at some point things went wrong, and after several attacks of cramp, and ‘a strained leg’, he was compelled to abandon the attempt on the fourth day having managed twenty-seven miles. ‘Folly Bridge may to some sound like an appropriate starting point for such an enterprise,’ remarked one journalist, but Easton had ‘plenty of pluck … He is, I believe, a milkman by trade - this perhaps explains his partiality for water!’

Although today no one seems to have heard of Easton’s four-day feat, it’s a clear precursor of modern-day endurance swims, and proof that since Victorian times we’ve seen the Thames as the ultimate challenge. Easton tried out different courses on the river and when he attempted a six-day swim no one, apparently, had ever thought of doing it before. It would be more than a hundred years before anyone did manage to swim between Oxford and Teddington, and that was Andy Nation as part of his non-tidal Thames swim in 2005. He had the same motivation as Easton - no one had done it before - although on this occasion he was also aiming to raise money for charity.

I find it strange that an event so widely reported at the time has now been forgotten; it’s as if each time someone in the twenty-first century attempts to set a record in the Thames they’re unaware that it has been tried before. I’m beginning to think that the history of Thames swimming has so many stops and starts that it will never be a straightforward, linear story; rather, we repeatedly need to flash back to the past in order to make sense of the way we use and view the river today.

I leave Folly Bridge and head to a very different river spot, a place for enjoyment rather than ‘sportsmanlike’ challenge. Tumbling Bay lies behind Oxford’s railway station, through Botley Park. It’s not clear when it first opened but in 1893 the town clerk put a notice in a local paper announcing that as from 5 May ‘this Bathing Place will be OPEN, Free of Charge, for FEMALE BATHERS ONLY, on each FRIDAY during the Season, between the hours of 6am and 8.30pm. Bathing Dresses will be supplied, Free of Charge, and must be used.’ In addition, a bathing attendant was engaged who would supply towels for a penny.

I walk past a community centre and across a field and I can hear the place before I see it, with a loud rushing sound coming from behind the trees. It’s not as big as I’d expected, a rectangle of water between two weirs rather like a concrete-lined lido. Two teenage boys emerge from bushes on the opposite side and as they cross the bridge towards me I ask if they ever swim here. ‘Yes,’ one says, ‘if it’s a sunny day. My eighty-six-year-old grandma swam here. It’s really packed in the summer. Some people say we shouldn’t because of that rat thing, but I don’t know anyone who ever got it.’ And is the current fast? ‘You can stand under the bridge if you need to,’ he says, then he points to the far end. ‘That part is weedy, but you can dive near the steps.’ There is gravel on the ground, and quite a few pike and perch, which he’s fished for in the past.

As the boys leave I walk around the pool; the bottom looks shallow and sandy and there are plenty of weeds and mud. On a hot day it must be a perfect place to cool off, and in the 1940s it was here that schoolchildren were taught to swim. ‘We didn’t have a bathroom at home, so the nearest I usually got to water was a quick rub round with a wet flannel,’ Bob Hounslow told the Oxford Mail. ‘The thought of immersing my whole body in cold water wasn’t one I relished.’ But at Tumbling Bay the instructor would order the scrawny boys to stand in a line in the water, then dive forwards, arms outstretched, ‘and glide along until we bumped into the weir’. The process was then repeated, using the swimming strokes they had learned lying on straw mats in the school playground. Eventually they managed the width and then the length of the pool and gained swimming certificates. Today the old changing rooms have gone except for their concrete bases, but the ladders remain - apparently to ensure the council can’t be sued if someone gets into trouble.

By far the most lethal place in the Oxford area is further downstream at Sandford Lock. ‘The pools of Sandford Lasher, in the backwater by the lock, are dangerous for bathing in, and have acquired an ill name from the many fatal accidents which have happened there,’ explained the 1893 Oarsman’s and Angler’s Map of the River Thames from Its Source to London Bridge. ‘The pool under Sandford Lasher … is a very good place to drown yourself in,’ comments the narrator of Three Men in a Boat, while Dickens’s Dictionary of the Thames notes, ‘It is notorious to all rowing men and habitués of the river.’ The Pool of Tears in Alice in Wonderland was a result of Carroll’s visit to Sandford, while Michael Llewelyn Davies, one of the inspirations for Peter Pan, drowned here in 1921. The lasher is described on modern maps as a treacherous weir pool with a very strong undercurrent, while the lock has the deepest drop on the non-tidal Thames.

While people still swim at Tumbling Bay and Port Meadow today, bathing in the Thames around Oxford is the subject of repeated warnings in the local press. It may once have been normal for schoolchildren to be taken to the river to learn to swim, a basic skill that everyone needed to know, but according to the media today it’s a dangerous pursuit. ‘The deadly lure of deep water during sunny spells has once again proved fatal,’ reported the Oxford Times in 2000, following ‘a long list of tragedies’. Youngsters are told ‘not to indulge in the dangerous “sport” of jumping into the water from river bridges’, and the Environment Agency (EA) estimates that ‘between 50 and 100 children a day can be found playing unaccompanied along the Thames’ as a whole. Swimming, it cautions, should always take place under adult supervision and ‘preferably in a swimming pool’.

The EA, established in 1996, is the navigational authority on the Thames, operating under legislation that goes back to Magna Carta, and owns the forty-one locks on the upper Thames, where swimming is banned, as it is in weirs. It is responsible for registering craft and generally managing any river activity. But Russell Robson, Waterways Team Leader, stresses that there is a free right to use the Thames: ‘we are not the owner of the river or of the water. The riparian landowners have rights to the banks and bed where their land adjoins the river, so if a house has a garden leading down to the riverbank then they own that bank. If you want to dive in we have no powers to stop anyone, but a landowner can restrict access and if there is damage then it’s trespass.’

While he says that in general people have become ‘softer’ with the introduction of indoor pools, there has also been a growth in mass-participation events on the Thames. ‘People see it as a fantastic backdrop for their event. You get the choice between an idyllic, tree-lined, sun-warmed river, or a twenty-five-metre-long municipal pool with hair floating in it. People have always paddled from the banks, fished, bathed, cleansed and played in it. The perception is it’s getting cleaner, which it is. I grew up in southeast London in the 1970s and the Thames was a floating rubbish dump. Today it’s an ever-improving environment for wildlife, but it’s not bathing water.’ The three main risks are the cold, flooding and possible infection, but ‘if people take precautions there is no reason why they shouldn’t swim’.

Yet while the EA monitors ecological and biological quality, there are no official bathing waters on the Thames, so it doesn’t test for E. coli or strep. ‘To be brutally honest, it wouldn’t pass bathing water standards,’ says Russell; ‘there is land drainage, water for agriculture and drinking water, power industries and wastewater discharge. Climate change means we have warmer summers and people are attracted to riverbanks. It’s a free activity and it’s more popular now, but that doesn’t mean it’s safe. People still go and swim at Tumbling Bay, although it’s not open any more, and there is a drowning there every few years.’

Perhaps the most dangerous activity on the Thames is jumping from bridges, which Russell says goes on all over the place with at least one incident every year. The annual May Day tradition of jumping off Magdalen Bridge into the Cherwell has led to numerous injuries. Recently the coroner at Oxford ruled on a case where a fourteen-year-old boy jumped into the Thames with his girlfriend, and hadn’t told her he couldn’t swim. ‘I’ve jumped from bridges myself and it’s great fun,’ says Russell, ‘but it’s also hazardous and I never considered that people just chuck stuff in.’ He cites stolen laptops and builders dumping debris: ‘we had twenty bags of rubble at Godstow and the diver was standing on it and the water only came to his knees.’ In the summer of 2012, the EA invited the public to Pangbourne, about twenty miles from Oxford, to watch Thames Valley Police Search and Recover divers remove hazardous materials by Whitchurch Bridge. In previous years divers had pulled out shopping trolleys, motorbikes, fridges, TVs, scooters, scaffolding and traffic cones, some firmly stuck in the riverbed. One year only a small sample of objects was recovered, partly because the diver was becoming entangled in a discarded fishing line.

The EA cites numerous possible risks associated with swimming and diving in the Thames, including falling on metal spikes, being struck by a boat or caught in a propeller, being swept along in a strong current, encountering cold water which can lead to cramp and breathing difficulties, and unstable slippery banks which can collapse suddenly. With warnings like these, no wonder people are put off and some Oxford residents, like Christopher Gray, think the idea of river swimming is crazy. ‘Though a tributary of the Thames flows at the bottom of my garden, I would never dream of swimming in it,’ he wrote in the Oxford Times, annoyed that the Daily Telegraph had just run a three-page feature on river swimming, recommending the Thames at Port Meadow and Clifton Hampden. To him this was ‘Barking mad … River swimming is a new faddish activity. Like motorcycling and Morris dancing, it numbers many zealots among its supporters.’

Several well-known endurance swimmers have fallen sick around Oxford, including Lewis Pugh during his 2006 trip. ‘The upper Thames was beautiful, clean and gorgeous,’ he remembers. ‘Oxford was really grotty. I ended up in hospital there, although we didn’t mention it to the press at the time. I had started vomiting late one night; I was rushed in and given antibiotics. The next morning I was totally exhausted, I only managed 400 metres that day.’

David Walliams fell sick at the end of day two as he passed Oxford and reached Abingdon. ‘I had Giardia, which people in the third world get from dirty water, and it makes you very ill with diarrhoea. It lays eggs in the lower intestine. I had antibiotics before I started, and during, and I can’t say for certain how I got it.’ Long-distance swimmer Frank Chalmers also got sick with ‘the dreaded Thames lurgy’ as he approached Oxford on his four-day swim, but despite being taken to hospital he says ‘people swim here all the time and they are fine’.

Indeed they are, and despite warnings from the EA and in the press, swimming in the Thames at Oxford is seeing something of a revival. ‘As the pound sinks and more of us stay at home instead of going abroad, such simple pleasures are being rediscovered,’ says Chris Koenig from the Oxford Times. ‘After all, the weather is getting hotter and the rivers cleaner.’ Swimming teacher Dee Keane has lived in Oxford for thirty years yet didn’t swim in the Thames until she took part in a full-moon swim with the Outdoor Swimming Society (OSS) downstream near South Stoke. ‘There was thunder and lightning and we were all a bit hyped up. We assembled in a field and changed and then walked through the village and a mile up the towpath, just wearing costumes and goggles, and then swam back. It was dusk, around 7 or 8 p.m., and people were coming out of the pub to look at us. You could see them thinking, “Dear God, I’ve got to stop drinking.”’

The dozen or so people swam with the current and, Dee continues, ‘I remember thinking, well, I’m quite glad it’s dark and I can’t see what’s in the water, what’s down there in the murky depths. But it was quite silky, with an occasional leaf brushing past.’ As for health risks, she says statistically you’re as likely to pick up a bug or a verruca from a pool. However, she swam the Thames with her face out of the water, ‘although I spend my professional life telling people not to do that because it places more stress on the back and neck. But in the Thames I was really careful not to swallow water.’

Esther Browning is another long-time Oxford resident, having arrived as an eighteen-year-old to study Human Sciences. One of the attractions was the river; she rowed for her college and was a member of the Wallingford Rowing Club, racing on the Thames as far as Putney. But then she had three children and rowing is ‘a massive time commitment’. However, she managed to complete some triathlons that included swimming in an indoor pool, and then one day she saw an advertisement for a triathlon that involved an open-water swim. ‘My big block was open water, but I felt like a bit of a fraud doing it in a pool.’ Esther lives near Newbridge, southwest of Oxford, and that’s where she first went into the Thames to swim, along with a friend - ‘I squealed in barefoot from a little mud beach, swam upstream and then back. It was a perfect summer’s day, and the water was gentle.’ She then took part in an OSS swim at Dorchester-on-Thames followed by swims at Port Meadow, Abingdon, Buckland and Wallingford. ‘All the stretches are different. North of Wolvercote is Amazonian with long branches hanging down, whereas at Newbridge it’s flat farmers’ fields.’ Then in the summer of 2012 she ‘hooked up with faster, more serious swimmers’ and now she and two other women - Kate and Katia - swim all year round. ‘Men say, “ah, it’s too cold to swim in the Thames”, but women are hardier, or women are every bit as hardy as men.’

‘People are put off by the cold of the Thames, but it’s so beautiful’: Katia Vastiau who regularly swims near Oxford with companions Esther Browning and Kate Bradley.

The three women try to swim every week, usually a 750-metre course through Abingdon. ‘As the days get darker we go there because the light from the town means you can see where you are. I’m terrified of cold water, it’s almost like I have to prove myself, but afterwards I’m always pleased. I get a kick out of making myself do it, there’s a real rush of endorphins. Before a rowing race I would feel nervous, my heart would be racing, and that’s what it’s like before swimming in the Thames. And it’s fun, we have a laugh, we wetsuit up and scamper through town. And we really laugh when we get out of the water and try to get out of our wetsuits, it’s very difficult when you’re cold. I’m surprised we haven’t been arrested for indecent exposure; you’re always baring more flesh than you intend. Kate and Katia really encouraged me, they’re really fast, and you need a group, you need companions.’

Esther says it can be quite scary in the dark with a strong current and sometimes it’s touch and go whether they will do it. The women can’t see each other, so they call out as they swim along, and while they tried wearing head torches these didn’t work well while doing front crawl. The Oxford trio post their swims on the OSS site and others join in. ‘A lot of people swim in the Thames. It’s going on all the time but the last couple of years Facebook has made it easier to hook up.’

Esther’s companion Kate Bradley first swam in the Thames in 2010 downstream at Clifton Hampden. ‘It was November, but it was incredibly warm for the time of year, about fifteen degrees. The second time there was frost on the ground and mist in the air and there were some shocked looks from the locals as we headed down to the river. There are still people who won’t go in the Thames and think it’s dirty; you could say David Walliams’ swim was bad publicity. But personally, after three years of swimming every week in the Thames, I’ve never been ill. There have been recent sewage leaks, but mainly it’s scare-mongering.’ As for other river users, ‘most rowers are friendly and fine but there’s the odd one … Once I nearly bumped into some and they thought we should be swimming under the trees and that we didn’t have the right to be in the river. But mostly people just say “you’re mad”. I try to be pleasant to everyone.’

Katia Vastiau, the third member of the group, first swam in the Thames two years ago. Originally from Brussels, she was a competitive indoor pool swimmer until the age of nineteen; she semi-retired from swimming, studied and had children and found there was no time for it. Then she met someone from a triathlon club who told her she should just do the swimming part. ‘People are put off by the cold of the Thames, but it’s so beautiful, we see herons and ducks and you see the edge of the river and the villages from a different angle. If you’re in a camper van you see one perspective, in the river there’s another. It’s pretty and mellow. By now we know where to get in and we know the currents, we’re not mad, we don’t just jump in, we know what we’re doing. We go on the left where there are no boats, but change if there’s a weir on the left.

‘Rowers are a problem; they don’t look where they’re going because they’re going backwards. We have bright hats and flashlights, but when we reach a corner we shout, “swimmers in the water!” There are lots of boats around Oxford. Rowers and their coaches usually say, “oh my God, you’re really brave” and are very nice. Sometimes someone might be a bit grumpy, having to reduce their stroke for five seconds. You have to keep sighting and to look at the rest of the group. We’ve never had a near miss. We have lots of chats with fishermen and people walking their kids, it’s very social.’ The women also pick up discarded packaging and plastic bottles and put them in their wetsuits because ‘we use the river; we want to help clear it up. We want to show people the Thames is there, but respect it.’

Swimming around Abingdon isn’t a new idea, and although they may not know it, the three women’s regular swims are building on a long tradition. In 1881 an official bathing place opened ‘at the back of the Island near Abingdon Lock Pool’ with floating screens moored across the back stream. Four days a week were ‘set apart for the ladies to have the exclusive right of bathing there,’ explained one newspaper. ‘We hear that a club has been formed by some ladies of the town for the purpose of learning the art of swimming.’

Abingdon was still a place for family dips in the 1960s and 1970s - as was Wallingford where, at the turn of the century, children had been taught to swim wearing safety devices attached to a rope and a stick. Tami Bowers, who was born and brought up in Abingdon, remembers swimming in the Thames when she was three or four. ‘My mum took us; she enjoyed swimming, though she wasn’t competitive. There was not a massive amount of people doing it, there was an open-air pool nearby that people went to and originally it had Thames water. There was a slight current, depending on the time of year, it seems stronger now but maybe I’m more aware. The Thames was always on my doorstep; it was a luxury I had, and a natural thing for me to swim there. At Abingdon you’re spoilt for choice.’ Tami has brought up her children, now fourteen and seventeen, to swim in the Thames, and the only experience of any illness was when her eleven-year-old Border Collie, Rebel, got Weil’s disease: ‘he spent nearly nine weeks at the vets and we didn’t think he would come out the other side. But as soon as he was well again he went back to swimming and he swam in the Thames until the day he died aged seventeen. He would run and jump in anywhere he could. He swam twice a day around Abingdon.’

Tami has taken part in mass events such as the Great London Swim, ‘but I prefer to paddle on my own, it’s me time’. However, she says anglers often don’t like open-water swimmers. ‘I’ve been catapulted with pellets and they’ve screamed at me to get out of the way. Boats don’t mind, the rowers aren’t a problem, and the fish like me, I know because I have pike nibble marks on my wetsuit which I wear in the winter.’

As I leave Oxford and take the train back to London I wonder what Charles Steedman, the Victorian author, would have made of modern-day swimmers around here. I think he would have loved it all; to know how far we’ve come, that while children may now be urged to swim indoors and many of the old bathing places have gone, the art of river swimming continues in the form of three women who swim every week in the darkness through Abingdon. We have tried out different ways to swim the Thames at Oxford, from one-off races in 1840 to four-day endurance swims fifty years later. In Victorian times ‘ladies’ were keen to learn the new art; now we plunge into cold water in wetsuits. Here we are again, returning to the Thames, and as the river winds its way south into Berkshire I’m keen to know what stories the town of Reading has to tell.