Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

24

Crowstone Swim

‘If you love something you don’t want to keep it to yourself’

Iain Keenan, founder of the Chalkwell Redcaps

When I get off at Chalkwell Station the transformation since I first glimpsed the foreshore from the train window this morning is breathtaking. Gone is the mud, now there is an ocean of water. The beach, however, looks dull and overcast; family groups are having a day out, but no one is actually swimming, just a handful of children splash and paddle, some clutching big inflatable toys. Perhaps they’re put off by reports of strong tides and dramatic rescues, as well as the recent advice from the ambulance service that deep water is cold enough, even on a hot summer’s day, ‘to take your breath away, possibly leading to panic and drowning’. On the other hand, unlike other spots on both the upper Thames and in central London I can’t see any warning signs about swimming, and there’s no information about lifeguards either.

I walk along the shore; the sand is as dark as Demerara sugar and I’m so intent on following directions to the Chalkwell Redcaps hut that when I spot, ahead of me, an obelisk in the water I almost don’t pay it any attention. But this is the Crowstone that marks the end of the PLA’s jurisdiction over the River Thames. The marker on the Kent side is the London Stone on the Isle of Grain, while the western marker is the London Stone just above Staines. There still remain questions as to where the Thames ends, though not nearly as many as where the river begins, but it’s the Crowstone that I’m swimming to this afternoon.

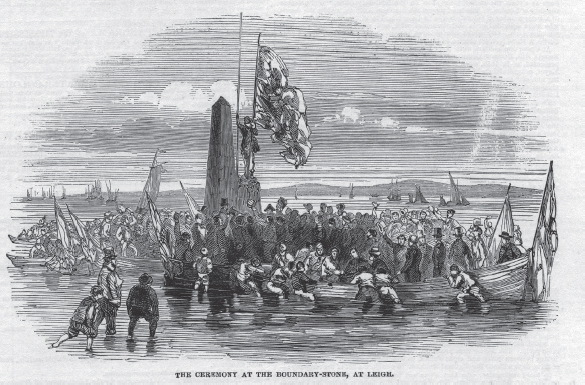

A ceremony held at the Crowstone in July 1849 when a pledge was given to preserve the City of London.

In Victorian times the stone was the limit of the powers of the Thames Conservancy Board. In 1858, the year after it took control of the river, Board members paid a visit to the estuary and found the Crowstone ‘having been comparatively recently placed there, is a prominent object, and is discernible at great distance’. Over a hundred years later, in the mid-1960s, Essex Countryside Magazine described it as, ‘standing tall and solitary on the foreshore at Westcliff-on-Sea’. It was, according to J. Blundell, an ‘obelisk with a difference’ and ‘uncommonly situated, its very presence demands explanation’. Erected in 1836 (although some reports say 1837), it joined a much earlier stone of 1755 (which itself replaced an earlier limit mark). Both stones stood together until 1950 when the PLA presented the older one to Southend Corporation for preservation in Priory Park, where it still stands today. The derivation of the Crowstone’s name isn’t clear. It may come from Crowes, a nearby settlement existing in 1536, or it could be because the stone was a favourite lookout post for beachcombing crows, which may explain how Crowes got its name in the first place. Starting in 1842, Blundell writes, there were ceremonial visits paid to the Crowstone and Sir John Pirie, then Lord Mayor, ‘first held the City sword and colours’ against the stone, which was then circled three times by boat or on foot. Wine was served, a pledge given to ‘God preserve the City of London’, and these festive occasions took place every seven years but ended when the Thames Conservancy Board took control of the river. An 1849 edition of the Illustrated London News includes an image showing ‘the ceremony at the boundarystone’ where a man stands, a massive flag held high, next to the Crowstone. He’s surrounded by people celebrating, some wading in the water, others pushing a boat, while he perches on top of the smaller, older stone that now stands in Priory Park. Other events were held here, too. In the summer of 1900 a local Baptist pastor baptised ‘four candidates by immersion in the sea near Crowstone, in the presence of the regular congregation and of witnesses’. So it’s a stone that has inspired a fair bit of ritual over the years.

I reach the Redcaps’ hut, marked by a red and black flag, open a side gate and walk in. Iain Keenan is waiting for me, as are his wife, Rachel, Ben Jaques, Jane Riddle and Jane Bell. ‘Do you want to swim now or later?’ asks Iain. ‘Now,’ I say, because I’m hot and sticky and desperate to cool off. They all look well kitted out, with endurance-style costumes, hats and goggles, and I feel a bit underprepared, especially as I’ve forgotten to bring a towel. But Iain lends me one and I get ready in the club’s wooden hut.

We walk a few steps to the beach and he explains the plan is to swim out to the Crowstone from in front of the hut, and then back. Suddenly I’m a little unsure; it looks a bit far away. But then again I can’t wait to get in, because although the water looks grey, back in February this year I was standing in my wellington boots at the official source of the River Thames in the meadow of Trewsbury Mead and here I am over 200 miles later. I’ve followed the course of the river at Oxford, Henley, Windsor and Eton. I’ve been on a boat to Hampton Court, strolled through Richmond and Kew, crossed the bridges through London and paddled at Greenwich. I’ve visited Victorian bathing spots and the sites of twentieth-century seaside city beaches, and at last I’ve arrived where the massive waterway ends. And now that I am about to end my journey I’d rather it went on. I want to go back upstream and visit the places I’ve missed in this story of the river. I’m a Londoner born and bred, so the Thames has never been far away from me, yet I’ve not really thought about it as a place to swim, even though I’m standing here in my swimming costume about to jump into the estuary.

I step over a small stone wall, walk down the beach and launch myself into the water. It’s refreshing, but at 22 degrees only just, and the taste of salt takes me by surprise because it’s been a while since I was in the sea. There are a series of poles in the water with green hats on top that mark the end of the groynes and serve as a warning to swimmers that there’s an underwater hazard between here and the foreshore. I’m told we will swim out to the last pole, go round it, and then turn left towards the Crowstone. The route on the way there will be easier than the return trip, as to begin with we will have the tide in our favour. As we set off the water is choppy and there is a strong swell and I realise I’m swimming across the incoming tide. It doesn’t seem to be helping me much; instead I’m being buffeted from the right, waves constantly slapping against my face. It’s not a difficult swim, but I am swallowing a lot of water and I think of Norman Derham in the 1920s and then more recently Peter Rae and Wouter Van Staden and how they set off to cross the entire estuary.

We’re being accompanied by a man in a kayak now, Jason Curtis, the founder of the Great Pier Swim. I think he’s just having fun, but it’s only later that I realise he’s my safety escort. It’s strange swimming with other people in the sea; it’s not something I usually do, except for when playing with family and friends. I have the urge to head off, but I’m already aware that the Redcaps know these waters and I don’t. Iain tells me to watch out for two windsurfers who suddenly appear in the distance and seem to be heading our way. If I was alone and not wearing a brightly coloured cap I don’t know if they would even notice me. Later he tells me we have right of way - but do the windsurfers know this and would it make any difference?

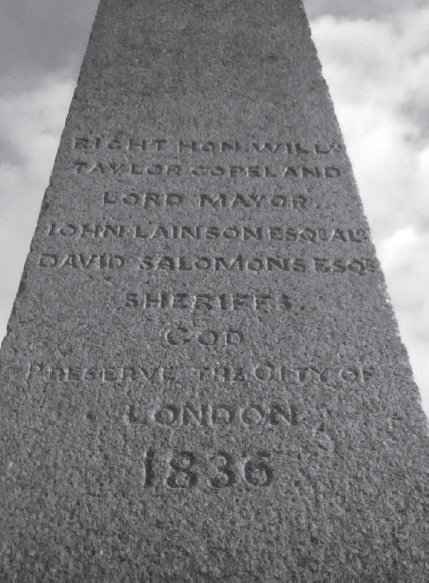

It takes some effort to swim, although the further out we go the water feels colder and that’s a relief. Now I’m reassured by the presence of the others: Iain is on my right, in his bright cap and goggles, the two Janes are ahead. One of them races off and I follow, but still it’s a bit of a battle. Then at last we get to the Crowstone and at once I’m thrust up against it: there is nowhere to cling, it’s so wide I can’t grasp it. So I touch its gritty edge, tread water and look up to its pyramid-shaped top. My first impression is that it’s so old, this grey monument that rises majestically out of the water. Letters are carved deep into the west side of the stone: ‘Right Honourable William Taylor Copeland Lord Mayor, John Lanson Esq, David Salomons Esq. Sheriffs, God preserve the City of London 1836’. On the east side is a list of names including Aldermen, Sheriffs elect, a solicitor, water bailiff and common cryer, presumably those who took part in the 1842 ceremony held by Lord Mayor Pirie whose names were then engraved on the stone. The writing on the south side, however, which faces the oncoming tide, is too worn to read.

Swimming back is meant to be harder but it isn’t, may be because I made it and it wasn’t far at all, only a 500-metre round trip. When I get out of the estuary I feel something sticky against my leg; for a second I think it’s a barnacle, but it’s only a sweet wrapper.

Inside the Redcaps’ hut a curtain divides women from men. ‘You’re really lucky having this on your doorstep,’ I say to Iain’s eldest daughter, Olivia, who joined us on a surfboard at the end of our swim. She’s thirteen and is concentrating on brushing her hair before a small sink, ‘I know,’ she says in absolute appreciation. We sit outside to have tea and biscuits, while the children of the various Redcaps play. To my far right two women are bowling; we’re at the end of their green. This Chalkwell open-water swimming club is just four years old and already the largest of its kind in the country. Just how did it start?

A view of the west side of the Crowstone, with the words ‘God preserve the City of London’ carved deep into the stone.

‘I began open-water swimming with friends and my daughters, Olivia and Maria,’ explains Iain, who lives a short walk away from Chalkwell Beach, ‘Olivia was nine then and she said put it on Facebook. I just thought it would be fun to start a club. I wanted a family activity; people don’t often swim in the sea as a family. She came up with the club name, in the sea you need something visual, so we called it the Redcaps.’

Swimming to the Crowstone with members of the Chalkwell Redcaps Ben Jaques and Jane Riddle, the stone is so wide it’s impossible to grasp. The club used the stone as a marker to swim round during their first estuary dip in 2010.

Ben Jaques, one of the first members, joined because ‘I’d thought about doing a similar thing, it’s nice to see people in the water. Triathlons have become more popular but people are still a bit scared to go in the sea, it’s a cultural thing, we’re told to swim in pools with lifeguards. The club gives you a way in.’ The group first met up on a bank holiday in May 2010, with twelve people, all of whom were locals, and decided to use the Crowstone as a marker to swim around. Iain contacted Richard Sanders at Southend Pier; ‘he said we could use a temporary buoy, so we would swim up to the Crowstone, across to the buoy and then back, making a loop. But we hadn’t quite anchored the buoy that first year and it drifted out and someone had to swim after it, he swam towards it, and there it was, still floating out … because he hadn’t realised it wasn’t tethered.’

The club then approached the council about the disused hut at the end of the bowling green, and were given a five-year lease, with an annual rent of £1,000. Club membership is £10 a year, and as well as paying rent and meeting other expenses they make an annual donation to the local lifeguard team. At the end of the first season they had forty people and it was then, just as with the new swims in Henley, Maidenhead and Chiswick, that they decided to make it ‘more legitimate’, rather than just a social event, and approached the lifeguards for support.

The Chalkwell lifeguards are a volunteer beach search and rescue unit, formed to help prevent incidents on the mudbanks along Leigh Creek and Hadleigh Ray. They are affiliated to the Royal Life Saving Society and have a kayak and foot patrol, but the volunteers only work on Sundays and bank holidays between May and September. The lifeguards were in existence by at least 1938, but were disbanded during the Second World War, and in 1978 they re-formed.

Nick Luff, club captain, later tells me there is a sign on the beach that refers to the presence of lifeguards, and more information is put up when they provide cover for the Redcaps’ events. ‘We’re trying to develop,’ he explains; ‘the other day someone asked, “are you new?” “No,” I said, “we’ve been going thirty-five years.”’

There are normally plenty of swimmers on the beach: ‘a couple of old boys have a ten-minute swim every single day and we see regulars every Sunday. Most are locals. The people from London, the day visitors, are more of an issue, they don’t know the area and they don’t know how to swim sometimes.’ But they have only had one serious incident in the last few years: ‘two girls were walking on the wooden groyne and one stepped off, her sister went in to save her, they were both in trouble. The coastguard rang us and when we got there, there were helicopters, air ambulances, fire engines, the lot.’ The girls had already been pulled out and saved, and just as in Victorian times neither knew how to swim. Nick is a police officer by day, but says there is no life-saving training for police any more: this stopped twelve years ago ‘to save costs’.

Meanwhile, Iain knew that as the club got bigger he would have to tackle the issue of public liability. He went to the Amateur Swimming Association, ‘but they couldn’t work out what we were doing, they gave me regulations for an indoor swimming pool club!’ So then he approached the British Triathlon Federation, the club became a member and by the end of year they were officially affiliated. The Redcaps bought a kayak and more buoys, and set out a schedule from April to October. They now have ten Crowstone Crawls a year, a 200-metre loop that is a social swim, attracting up to seventy people. Other events include a Christmas Day and New Year’s Day swim, a club relay, aquathlon and a championship race. The Christmas Day swim started in 2010, and raises money for charity. ‘A woman in a bikini, elves, a snowman and Santa were just some of the colourful characters who plunged into the chilly Thames Estuary,’ reported the local press on the swim’s second anniversary. ‘The Chalkwell Redcaps open-water swimming club proved they were made of tough stuff by braving the icy waters.’ Sixteen members met opposite the Arches café on Westcliff-on-Sea seafront for the charity challenge, ‘hardy members managed to stay in the water for several minutes while others, after being fully submerged in the water, didn’t stay quite as long’. They now have 240 members aged between seven and eighty-two. Women make up the majority of the club; the overall average age is between thirty-five and forty-five, and there are twenty junior members.

‘The club gives you a network,’ says Iain; ‘to do something like what we’ve done today, inviting members to come to the hut at 2 p.m. for a swim.’ But it is hard work, especially as he’s a full-time nursing lecturer at Essex University. ‘My reasons are personal, there are very few things we can do as a family and the Thames is on our doorstep.’ It was also personal reasons that led him to come up with forty open-water swims to mark his fortieth birthday, with at least two every month, all without a wetsuit. Again, he started it for pleasure and fun, then people learned of his swims and offered sponsorship, so he swam on behalf of the cleft palate charity Smile Train. His penultimate swim meant packing his work clothes in a dry bag and swimming 1.4 miles to Southend Pier. He then put on his work clothes and set off on a five-minute walk to the University of Essex’s Southend campus.

The Redcaps now work with the organisers of the Great Pier Swim, launched by Jason Curtis at Havens Hospice. Initially this was three kilometres from Jubilee Beach near the pier to Thorpe Bay, then they linked up with the Redcaps and came up with a new route. The challenge now goes from Chalkwell Beach to Jubilee Beach, and means swimming under the longest pleasure pier in the world, just as in Victorian times the Southend Swimming Club held its annual long-distance swim from the pier head.

Jane Bell has done the Great Pier Swim four times in a row, and before she joined the Redcaps she ‘had little knowledge of how the tides work in Southend, as I didn’t grow up here. I was perhaps a little reckless, swimming alone straight out from the beach rather than in a group along the shore as we generally do now.’ Jane Riddle, on the other hand, has lived in Leigh all her life: ‘I remember the tide coming in around me when I was only about five years old and a man having to rescue me from the mudflats. That memory has stuck in my mind all these years and I’m now forty-six!’

I ask if they ever come across jellyfish. They all nod; everyone here this afternoon has been stung. Jane Bell’s turn came at 1.30 a.m. when she was stung on her face by a jellyfish the size of a hand, but while she wouldn’t want to experience that again, swimming in the estuary is a passion and it hasn’t put her off.

The sun is going in again, I’ve dried off and it’s time to go. I ask Iain if he feels the Redcaps are bringing back an old tradition of swimming at Southend. ‘That tradition has been wiped out,’ he says. ‘The big issues today are Health & Safety and safeguarding kids. You didn’t have that in Victorian times. What we’re doing is writing a whole new chapter.’

If this is where my downstream trip ends then, like Iain, it’s time to look to the future, and every time I think I might have gathered enough stories about swimming the Thames, I come across new ones just about to happen.