Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

23

Southend

‘The estuaries of rivers appeal strongly to an adventurous imagination’

Joseph Conrad, The Mirror of the Sea, 1907

It’s 9 a.m. in mid-July, the first week of the school holidays, and I seem to be the only person on the train from Barking to Southend Central. The longest heatwave for seven years has just come to an end with dramatic thunderstorms, but the air is still hot and humid. As the train stops at Benfleet and then Leigh-on-Sea I catch glimpses of foreshore and boats moored on land like metal crabs, while at Chalkwell the tide is so far out there are miles of mud. I get off at Southend where the paved pedestrian street is deserted and a lone seagull screams in the air. Southend is a seaside town not yet open for the day. Only it’s not really a seaside town, it’s an estuary town, where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea in one of the largest coastal inlets in Britain. A major shipping route for oil tankers, ships and ferries, it’s tricky pin-pointing where exactly the estuary ends or begins. The western boundary is said to be Sea Reach, near Canvey Island, while the eastern boundary is a ‘line’ drawn from North Foreland in Kent to Harwich in Essex. It’s that imaginary line (or variations thereof) that has posed a serious swimming challenge both in the 1920s and today.

For novelist Joseph Conrad the Thames Estuary was a perfect place for adventurers, a route both to and from the empire. He lived upstream in Stanford-le-Hope in the 1890s and Heart of Darkness opens on board the Nellie, a cruising yawl: ‘The sea-reach of the Thames stretched before us like the beginning of an interminable waterway … leading to the uttermost ends of the earth.’ Conrad’s later novel The Mirror of the Sea, published in 1907, has much the same theme, with the estuary promising ‘every possible fruition to adventurous hopes … Amongst the great commercial streams of these islands, the Thames is the only one, I think, open to romantic feeling.’ Unsurprisingly, considering its location, there is a long tradition of swimming in Southend, for both competition and pleasure, and it was the training ground for two noted Channel champions.

Its reputation as a resort began in Georgian times, and its beaches and good rail links with London led to an influx of summer visitors. In Victorian times Southend was mocked by comic writers for its ‘cockneyism and vulgarity’, but it was a clean, quiet town according to Dickens’s Dictionary of the Thames, the air fresh and invigorating, ‘a well-built, well-arranged, and old fashioned watering-place’. ‘’Arry occasionally descends upon the place in his thousands’, and was to be found on the pier where ‘arrayed in rainbow tweeds, he delights in fishing for dabs’. The bathing machines on the beach were well used ‘although the strict rules of decency are not observed as well as could be wished’.

The bathing machines are long gone, of course, but the famous pier and its railway line still stands. I get the first train of the day, ducking my head to get into a carriage with shiny brown bucket seats. It rattles off like a ghost train ride, and there must be plenty of ghosts around this pier, first built out of wood in 1830 and then replaced with iron in the 1870s. It has survived fires, collisions from barges and boats and two world wars. Yet here it still is, the longest pleasure pier in the world at 1.33 miles, and it’s had a tram (and then railway) running along it since 1890.

From the window I see patches of water, clean and clear, then mudflats, and then finally the estuary proper. It looks broody today; a low purple cloud hangs over the landscape like a bruise. I get off the train and walk to the edge of the pier and put 50p in a talking telescope. A recorded voice tells me I’m opposite the Kent coast and the River Medway. There doesn’t seem much to swim towards except for what look like factory chimneys. At the far end of the pier is the RNLI station, and before that a restaurant with a large decked terrace. No one seems to be around and there isn’t much traffic on the water either; a sailing boat passes by and I can see a dredger in the distance near Canvey Island. To my left is the North Sea, a shimmering horizon lit up in a sudden burst of sunshine interrupted only by a single silhouette of what looks like a huge building. To my right the river heads towards London, to distant chimneys and the crest of a low hill. There are, as Conrad wrote over a hundred years ago, ‘no features to the land … no conspicuous, far-famed landmarks for the eye’.

As I walk back along the pier the air is silent but for the water gently sloshing underneath, the flap of tape warning about wet paint, and the rattling clatter of the returning train. The mudflats near the shore look like a sheet of ice. Unlike other piers, such as in Brighton, there isn’t actually anything to do on the long walk back except enjoy the views. There are places to sit, and two drinks machines with a big sign saying ‘Thirsty?’ and then a smaller sign saying ‘Out of order’. There is little evidence of modern life, but for regular no smoking signs, until I come to the end and there is the carnival of Adventure Island, an amusement park opened in the 1970s. I turn back and look along the pier; the ‘building’ I thought I saw near the North Sea is now clearly a massive boat.

A council booklet on the history of the pier makes no mention of swimming, yet it has been associated with races since Victorian times when the town hosted summer regattas with rowing and other events. In 1873 the press reported that ‘the annual aquatic festival was conducted … with even more than the usual spirit, and passed off with the accustomed eclat … the swimming, considering the state of the water, was most excellent’ and ‘there was the usual laughter splitting walking the greasy bowspit for a pig in a box’.

In May 1894 the Southend Swimming Club was formed and it ran an annual long-distance swim from the pier head. In the summer of 1909, the course, presumably along the length of the pier, was completed in fifty-five minutes.

The most famous club member was Norman Leslie Derham and in 1926 he was chosen as their candidate for an attempt to swim the Channel. Lord Riddell, owner of the News of the World, then the largest circulation paper in the world, was offering £1,000 to any English person who could beat the time set by an American swimmer. In other words, Gertrude Ederle, who that year had swum from France to England in fourteen hours thirteen minutes. In 1923 another American, Henry Sullivan, had swum from England to France in twenty-six hours fifty minutes.

Southend Swimming Club’s most famous member was Norman Derham. The future Channel champion trained in the Thames.

Derham’s archives are housed in the Southend Museum where Ken Crowe, Curator of Human History, has left them out for me. I’m expecting a few press reports; instead I find a large cardboard box on a table in a top-floor office. The first item is a neatly folded letter, several typed pages written by Derham’s daughter, Penny, who describes her father as ‘perhaps the last of the great adventurers’. I can’t believe my luck, I’m actually going to read about him in the words of a family member. Born on the Isle of Wight in 1897, his family originated from Germany, and were ‘lower landed gentry’ with a long naval tradition. In his early teens he was a midshipman cadet and before he was twenty he had ‘travelled three times around the world’. Conrad unsurprisingly was one of his favourite writers. During the First World War Derham joined the Royal Flying Corps, while in the Depression he worked as a pig farmer, an iron and brass bed manufacturer and a distributor of Fyffe’s bananas.

He later travelled to Canada and spent a season exhibition swimming with Johnny Weissmuller, the swimmer and actor who became known for playing Tarzan, before he went to Germany to become a glider pilot.

I’m entranced by Derham’s story, until I turn the page and Penny suddenly declares that her father was an admirer of Adolf Hitler, because of what he ‘was doing for the material welfare and advancement of his then bankrupt country’, although he also warned that the German leader was a ‘mad dog bent on conquering Europe if not the world’. Then Penny feels the need to confess something; sounding hesitant and asking for her father’s spirit to forgive her, she writes that he had ‘a tendency to Anti Semitisms’. I stop reading, feeling shocked; what does she mean by a ‘tendency’? But then she adds that this ‘did not prevent him from volunteering to swim around the “St Louis” [in 1939] when it was off Plymouth to assist in picking up the Jewish Refugees who had planned to join hands and jump into the water rather than return to Nazi Germany when no port due to International Red Tape would allow them to land’. The way around this was if they were picked up out of the water. Her father’s view was that when you saw someone drowning ‘you don’t stop to ask his religion and look at the colour of his skin’ but get in the water and try to rescue them.

I refold Penny’s letter, still wondering about Derham’s character and prejudices, and put it back in the box, to find the next document is his very own thirty-one-page ‘my life story’. He could swim by the age of six and at seven had made up his mind ‘that I should swim the Channel and do the same as Captain Webb had done … I could stay in the water and swim for hours if they would only let me.’ As a twelve-year-old he swam a ‘few miles’ to East Cowes from Newport, and in 1911, when Thomas Burgess swam from England to France, this ‘again fired my imagination to conquer the Channel’. Taking advantage of his parents being away he swam for six hours from Osborne Bay to Calshot Point.

In 1921 Derham moved to Southend, still aiming to do the Channel, and a few years later he set ‘myself the task of swimming the Thames Estuary’. On 4 June 1925, he made his first attempt, giving up after four hours because of cramp, but earning the name Sinbad the Sailor as ‘several miles from the shore a large porpoise rose to the surface beneath me, lifting me completely out of the water’. A porpoise? I stop reading again, picturing Derham midway across the estuary riding for a moment on the back of a harbour porpoise.

Then, on 10 June, he managed the crossing of thirteen miles in five hours and modestly explains, ‘I may mention that this was the first and only time that the Thames Estuary had been conquered.’ He doesn’t describe his route; one press report says his five-hour swim was from Southend to Sheerness, another that on his third attempt he ‘successfully swam across the estuary from Sheerness to Westcliff … starting on the Kent side he had 500 yards’ expanse of mud to walk’ and ended at the Southend swimming bath. So perhaps Derham tried it in both directions.

Either way, his stated aim now was to beat Montague Holbein’s fifty-mile Thames swim of 1908. Derham was clearly aware of the swimmers who had come before him; first he wanted to emulate Webb, then he was inspired by Burgess, and so, unlike many women Thames swimmers, he saw himself as part of a glorious tradition. He knew what other men had done and he wanted to beat them; his motivation was to set a new record, to achieve fame like them, and, considering that he later took up the challenge from the News of the World, to make money as well.

On 2 August, in pouring rain, Derham started from Putney Bridge and swam to Woolwich, but was forced to give up after twenty miles, again because of cramp. ‘They fed me with tomatoes and anything they had,’ he explains, ‘and it is a wonder that I did not sink long before I reached Woolwich.’ He then swam twenty-one miles from Blackwall Pier to Gravesend but ‘the condition of the water [was] terrible’. The press explained that with just three miles to go he was ‘made to swallow more of the odoriferous and heavily chemical laden water of the lower Thames than was good for him’ when tugs and steamers went past just after the Woolwich Ferry. At Barking Creek an outward-bound Belgian steamer ‘saw fit to open her bilges just as she was level with the swimmer … it made [him] terribly sick and although bodily he was strong, he looked as though he had been poisoned’. Derham was ill for three weeks and decided he’d had enough long-distance swims for that year.

In July 1926 he began his first Channel attempt, but a heavy storm meant he stopped five miles from the end. His next attempt came on 2 September. ‘A London paper had offered a prize,’ he explains, ‘and I was advised by my wife to start from France … she said “why not go the easiest way and win the money?”’ He started from Cap Blanc Nez but only two miles from the end fog ‘robbed me of a certain victory’. On 16 September he tried again, covered in 10 pounds of grease, and this time he made it despite being so dazed and exhausted that just 15 yards from land he rolled on his back and lost direction. Then finally his feet touched bottom: ‘I shot up my arms and proclaimed to the World that I had conquered.’

Pathé News was there to see Derham arrive, filming him yards away from shore, where he was making no progress at all until a group of women swimmers enter the water, clapping and urging him on. Out he trudges, his limbs almost flopping as he emerges on to land. A few shots later he is fully dressed and combing his hair, beaming uncontrollably. And no wonder: he was the first Briton to swim from France to England, from Cap Gris Nez to St Margaret’s Bay, in ‘13 hours, 55 minutes’, and the third British man to cross the Channel after his heroes Webb and Burgess. And, of course, he had beaten the American Gertrude Ederle, knocking around forty minutes off her time. Naturally the British press was ecstatic and he was photographed leaving the News of the World offices both ‘chaired’ and cheered.

I leaf through the rest of the items in the box; someone has certainly put together a treasure trove of memorabilia, perhaps it was Derham himself. Postcards show him with slicked-back hair and a black swimming suit with the Southend Swimming Club badge; others depict his final moments as he reached shore. There is also an envelope of congratulatory telegrams sent to 5 Holly Gardens, Southchurch Road, Southend, just a few minutes’ walk from the museum. One is from the founder of the Webb memorial, Alfred Jonas, who congratulated him ‘on your regaining the glory for England’; another is from the president of the Otter Swimming Club. There is also a telegram sent from Derham himself, ‘DONE IT WHAT DO YOU THINK OF THE OLD MAN NOW HOME TONIGHT LESLIE +’. Presumably these brief but triumphant words were sent to his family. The ‘old man’ had finally proved himself.

Derham received an enthusiastic welcome in Southend: flags were hung out, there was a civic welcome by the Mayor, dinners in his honour and a parade around the local football pitch. But, like Webb before him, now he had to come up with something new. His daughter, Penny, recalls him setting off from Tower Bridge to try and break a world record for canoe paddling, having designed and built ‘a sort of canoe with broom handles for paddles’. He began on the tide ‘one very murky peasouper evening’ and was nearly run down three times in the estuary before giving up. The press headlined the attempt: ‘Reckless Adventurer or Bizarre Suicide Attempt?’ The date isn’t clear, but in April 1928 he set off from the sunken garden at Southend in a collapsible boat with a passport in his pocket intent on reaching France. But a mile from the pier head a large wave overturned him and two hours later he was rescued. The following month the Southend Pictorial Telegraph shows him in a small Gaskin Ships’ lifeboat leaving Westminster Bridge to ‘conquer the channel again’. Presumably this ended in disaster, too.

In 1929, after having ‘a complete rest from long distance events’, Derham again decided to return to the Channel. He was also training a ‘Mrs. Coleman’ of Kentish Town in London, who was preparing for her Channel swim ‘under his supervision’ at Southend. Coleman had already shown ‘that she possesses the requisite stamina in a number of long-distance trials from Tilbury down the Thames’. Another paper reported ‘BIG SWIMS BY MOTHER AND DAUGHTER’ with ‘Mrs. Coleman, the well-known swimmer and her wonderful eight-year-old daughter, Edna, who recently swam five miles in the Thames in remarkable time, are now in Southend training for two big swims’. Edna Coleman would tackle Southend to Sheerness; her mother would attempt Tilbury to Southend. By now another swimmer called ‘Mrs Inge’ had created ‘a record for a Thames Estuary Swim’ in 1928 between Gravesend and Southend. She swam ten miles in two hours forty-three minutes, in the face of a strong easterly wind.

By 1938, however, Derham was working as a swimming pool superintendent. ‘I thought I was made,’ he told the press, ‘but the world forgets quickly. For a year or two I have lived like a lord, but in the long run I lost money over it. And then I had to find a new career.’ Now he had another idea: he would be the first to glide across the Channel ‘from a straight take-off … And then I think that will be enough records for me.’ It doesn’t look like this was successful and, when Derham died at the age of forty-seven, the local paper described him as ‘Southend’s greatest ever swimmer’. His club, Southend-On-Sea Swimming Club, still exists today; members train in indoor pools not in the Thames, and it has fielded a number of Olympic swimmers, including Mark Foster and Sarah Hardcastle.

Norman Derham attempts to boat down the Thames and ‘conquer the channel again’ in 1928.

I leave the archives and head back to the pier, thinking of another champion Channel swimmer, East End insurance clerk Edward Temme, known as Tammy, who also chose the Thames Estuary as his training pool. He became the first person to cross the Channel in both directions; in 1927 he swam from France to England and in 1934 from England to France. Tammy, who trained at Leigh Creek, was 6 feet 2 inches and weighed 200 pounds and was said to ‘romp across the surface of the sea like a porpoise’. He was also a member of the British water polo team at two Olympic Games.

Other would-be Channel swimmers similarly came to Southend to train, such as Eva Coleman - it’s not clear if she was related to the ‘Mrs. Coleman’ whom Derham trained. In 1933 the press reported ‘Girl to Attempt Channel Swim Training Diet of Steak and Peaches’, describing Coleman as having ‘big brown eyes, black hair, an infectious laugh, and a swinging, supple-limbed stride’. Coleman worked as a cashier at a hotel in the Strand in London. Her mascot song was ‘This is My Lucky Day - l’m Going to Win Through’, and she was determined to have it playing on a gramophone on the accompanying boat, saying she could swim much better to music. Her motto was ‘No slimming for swimming’; just like Agnes Beckwith and Annette Kellerman before her the effect of swimming on women’s weight seemed to be of some interest, although perhaps she was just answering a question from the press. She was said to ‘hold a few records’, including a twenty-one-mile swim in the Thames, and a ‘seven hour test’ at Southend.

Some swimmers, meanwhile, attempted to swim upstream from Southend. Pathé News filmed a race to Gravesend, ‘up the mouth of the River Thames’ sometime between 1920 and 1929. Competitors, both women and men, can be seen swimming against the current, although the water looks eerily calm. In modern times there is only one person who has officially swum across the estuary and that is Peter Rae who, in 2003, swam from Southend to All Hallows in Kent and then back to Leigh. The idea started as a bet, just as many other Thames swims have done, whether Victorian races or the modern Chiswick swim. Peter was having a pint with friends one day on the Bembridge, the headquarters ship of the Essex Yacht Club, when someone proposed a challenge. Could he swim across the Thames Estuary and then return to the Essex shoreline within one tide? This meant he had about five hours before the water retreated and there would be a mile and a half of mudflats again.

Peter thought he could. An experienced open-water swimmer ‘with a fair few miles under my belt’, eighteen years earlier he’d crossed the Channel. While this swim would be much shorter, he could similarly expect cold water, jellyfish, strong currents and tide. The main hazard, however, would be crossing busy Sea Reach shipping lanes. While Peter swims competitively, and started Masters swimming in 1994, he says he prefers just doing it for enjoyment. ‘Open water I like the best, I just enjoy the freedom, it’s almost a form of meditation.’ However, he hadn’t swum much before in the estuary.

It took him five months to plan the trip, liaising with the PLA and raising around £3,000 in charitable pledges. ‘I assumed I would have to go to the PLA, and because of my sailing experience I knew the shipping channel. I produced a plan and explained how I would be accompanied, and what my abilities were. I had no problem at all with the PLA. I’d done a lot of homework.’

His correspondence bears this out. In July that year he wrote to the Harbour Master to seek ‘advice and support’ for a sponsored swim to raise funds to convert HMS Wilton, due to replace Bembridge as the headquarters of the Essex Yacht Club. Sponsorship would be based on the number of completed miles, with a further bonus for completing the swim within one tide. He was originally to start from Jocelyn’s Beach in Leigh ‘as soon as there is sufficient water’, and the swim would be abandoned ‘if wind strength exceeds Force 3 or visibility is below 4 miles’. Unlike Derham and Tammy before him, Peter would have a whole series of safety measures in place. He would be accompanied by a yacht, Uncle Ronnie, carrying a ladder, life belts, life jackets, flares, fixed and portable radios, and equipment for hauling a body both horizontally and vertically from the water. The skipper would be Stuart Silcock, a qualified Offshore Yachtmaster, and Peter would be supported on board by at least three crew, one of whom would be ‘dedicated to monitoring and supporting the swimmer’. Both the local Coast Guard (Shoebury) and RNLI (Southend Pier) would be fully informed before and during the swim and ‘while the traffic in the Sea Reach should be minimal on the planned date the Yacht/Swimmer will ensure that they do not present any hazard to shipping in the channel. If necessary the swimmer will exit the water well before a potentially hazardous situation arises.’

Peter Rae’s swim across the estuary in 2003 started as a bet; could he swim from Essex to Kent and back within one tide? Here he’s about to strike out from the beach in All Hallows for the return leg to Leigh on Sea.

Peter would wear a full-body neoprene Tri-suit and yellow swim cap for warmth and visibility, and be provided with isotonic drinks at regular intervals. Finally, he explained he was forty-nine years old, of excellent health and fitness, and had recently competed in the 2003 European Masters Swimming Championships where he took a bronze in the 400 metres freestyle and silver in the 5,200 metres open-water swim. Peter was then ranked first for his age group in Great Britain and, aside from his Channel swim in 1985 in just over eleven hours, he’d also made an eight-hour double crossing of Lake Geneva.

He got the go-ahead and at 12.20 p.m. on 14 September he started next to the Westcliff-on-Sea casino, the air temperature was 18 degrees, the sea a ‘positively balmy’ 16 degrees. He set off to cross the estuary ‘in two feet of water, but it was just enough to swim in’. After one hour and fifty minutes he was standing on the beach at All Hallows, having avoided a large tanker in the main shipping channel. ‘A dredger was coming down,’ he remembers, ‘ships had been warned there was a swim in progress, it was not a close shave but the dredger had to be contacted by phone. The PLA had given notice about my swim to shipping but maybe the dredger didn’t heed it. It wasn’t dangerous but there are a huge amount of ships and with the new container port there will be even more.’

Curious well-wishers came out to welcome him at All Hallows, where he had a chicken sandwich and a cup of tea, replaced his cap and goggles and struck out for the Essex coast. ‘No one was expecting me, people at the yacht club came out to say “hi”, but I was only there for five minutes.’ Things then turned tough and he had to fight increasing wind, waves and another hour of incoming tide, as he was pushed towards the Shell Haven oil refinery behind Canvey Island. But he recovered his energy and, using the strengthening outgoing tide, the Bembridge was now in sight. After four hours and twenty-five minutes, covering eleven miles and with 3 feet of tide still available, he landed on the east slipway of the Essex Yacht Club to a ‘rapturous champagne welcome’ from members supporting and sponsoring the swim.

His advice to others is that the Thames Estuary is ‘for someone who enjoys a challenge. It’s not a particularly tough swim, it was not too cold, and it’s not big seas, though it can get choppy, and I was going with the tide.’ But he says Derham’s crossing in the 1920s ‘would be a no-no now, you couldn’t take the course he took because of shipping’. Just as with Matthew Parris, who swam across the Thames in central London, Peter says, ‘Yes I would do the estuary again; living here and looking at it every day … I just need to pick a nice day.’

Another famed swimmer to arrive in Southend was Lewis Pugh, at the end of his swim along the length of the Thames in 2006. A crowd of ‘more than 250 people turned up to watch him finish,’ explained the press, and ‘as the polar explorer and endurance swimmer emerged from the water onto the slipway cheers and shouts of “well done” rang out’. Lewis’ main memory of his final leg of the Thames from the barrier to Southend, however, was ‘plenty of jellyfish’.

Charlie Wittmack, the American adventurer who swam the Thames in 2010 as part of his world triathlon, had a rather different experience near Southend where he discovered first hand just how dramatic tides in the Thames can be. First, like Lewis, he swam through lots of jelly fish: ‘it felt like I swam through them for an entire day, and got quite a few stings’, but then ‘across from Southend’ he got stuck in the mud. ‘It was unexpected; we calculated the tides wrong so the swim took a lot longer than we thought. The sun was setting, we were nowhere near where we needed to be, so we pulled up to the shore to make a phone call and take a look at the GPS. As we were standing there, over the course of just a few minutes, the tide really truly went out, and we realised we were essentially stuck in the mud. It was getting dark, we couldn’t see where we were, and the scariest thing was we really couldn’t work out where the water was going to end up being, it was just cutting back so dramatically from where we thought the shore was. So we got in touch with the rescue boat service and within an hour or so they had picked us up. They even gave us a place to stay, they were very encouraging, it was kind of a lot of fun.’

Meanwhile, although Peter Rae gained official permission for his estuary swim, at least one person has done it without. ‘I have always wanted to swim the Thames,’ says Wouter Van Staden. ‘I always had the idea that if you can see something then you can swim to it. I live in Basildon and, being in Essex, when you get to the coast you can see Kent, so I wanted to swim there.’ Wouter comes from Pretoria, South Africa, and knew ‘a bit about the Thames’ growing up, but it ‘wasn’t big on my radar’ until he came to England. In 2007 he settled in Reading, and ‘for around six months I tried to find information if I could swim in the Thames, but I only heard stories about sickness. Then I read about a pensioner swimming near Maidenhead and I was convinced the Thames was swimmable.’

On 23 May 2010 he swam from Canvey Island to All Hallowson-Sea, covering just over two miles. ‘I read about rights and permissions and figured I needed to speak to the PLA but in the end I thought there was a chance they would say no, so I thought I would just risk it. I moved my kayak to Canvey Island the day before. I just knocked on someone’s door and said, “can I please leave my kayak in your garden?”’ The next morning he went back to get it with his wife, Anecke; ‘she was to be in the kayak and she was not entirely willing but everyone else I had asked couldn’t do it. We did it in the early morning to avoid the pleasure craft, so there would just be big ferries and tankers. There is a short dredged section of around 400 metres wide with big craft and so it was sort of safe and sort of not, because if they come across you they have nowhere else to go. After the central channel a ferry did pass and I believe it notified the coastguard that there was a swimmer in the estuary, although I had already passed the channel by then. They sent out a boat and I saw it roughly as I got to Kent; it was too shallow for the boat to come any closer but I noticed them and as I headed back I went straight for them. They asked what was going on and “are you fine?” They said they were obliged to stay with us until we reached land. They offered to quicken the process and so we put the kayak on their boat and they gave us a lift back. I wasn’t going to swim both ways anyway. I had missed my train and started late so it took longer than I thought.’

It took him around two hours. ‘The tide had moved too much to swim back to Canvey so I was kayaking anyway. They interviewed us and asked what safety precautions we had and took our names and numbers and address, which my wife was not happy about, but I didn’t break any rules or regulations.’ But he says since then he has always been in contact with the PLA, and he still does long swims, but along the shore and sometimes to the Mulberry Harbour. Here there is a ‘Phoenix’ caisson, lying on a sandbank off Thorpe Bay, part of a temporary harbour intended to be used in the Normandy landings following D-Day. But it sprang a leak and was brought into the Thames Estuary and allowed to sink. ‘It’s visible from the shore and so I wanted to swim to it,’ says Wouter, who has now done the route twice, along with others. ‘We notify the coastguard, saying when we are going and where and how many of us there are and we tell them once we’ve arrived back. I’d definitely like to swim the estuary again and I probably would, but I don’t have a lot of time.’ He works for a car rental company and with the new Southend airport is very busy. But he has more plans to swim the Thames, this time through London. His aim is to travel the length in sections, and he’s already done a three-day swim from Cricklade to Radcot Lock. ‘I’d like to swim to Southend. If you time it with the tide you can do large distances in one go.’ He would swim through central London doing ‘a twenty-kilometre stint at night and I could do it in three or four nights’, and this time he says he will approach the PLA first.

While the Southend area is clearly home to some experienced and ambitious swimmers, others can be reckless, as Richard Sanders, pier and foreshore supervisor, knows only too well. He meets me where the pier train begins and I follow him down to offices below. We walk along a corridor and stop at a conference room where Richard opens the door a little cautiously, saying he’s looking for the two ‘ship’s cats’ as they have a habit of opening doors. That’s when I realise it feels as if we’re on a boat; even his white uniform gives him the air of a sea captain. A long, thin table runs the length of the narrow room, like a ship’s mess, while in the corner is a big display board ‘Visit Southend - town, shore and so much more’.

Richard is from Southend but doesn’t swim in the Thames; his swimming memories are of his dad taking him to the indoor baths on Sundays. ‘There were bad news stories when I grew up,’ he says, ‘about sewage and tall tales about people contracting things.’ But he stresses that maritime law has changed a lot, and now passing passenger ships and tugs can pull up at the end of the pier and their sewage is pumped to the shore, not dumped into the sea. The method is described as ‘ship to shore’ but is otherwise known as ‘shit to shore’.

As evidence of its cleanliness the estuary is well populated with flat fish like sole, there is a nearby colony of seals, and in 2008 the Zoological Society of London found a breeding population of endangered seahorses. ‘Our waters have improved massively,’ says Richard, ‘the Thames is not the dirty urban waterway it used to be.’ He compares the estuary to places like the Maldives, ‘which is seen as paradise, but while one side is, on the other they dump their sewage’. As for the tradition of swimming, he points out of a row of small, partly frosted windows in the direction of the Westcliff-on-Sea casino: ‘there used to be swimming baths there, there was an inlet that was tidal-fed, and people have told me about swimming in the 1950s.’ There was also a sea-fed dolphin pool and boating lake east of the pier with two dolphins.

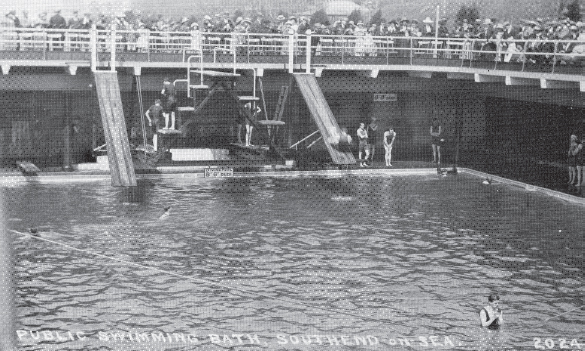

Southend has a long history of Thames bathing; in the 1920s people enjoyed open-air swimming baths complete with slides.

When it comes to swimming today, ‘there are incidents,’ he says carefully with what turns out to be great understatement; ‘people swim to the shore against the tide and they swear they are Olympic-standard swimmers and end up going backwards. The tide is six knots and most people can’t do that.’ The Hadleigh Ray, a body of water near the pier in the direction of the casino, can be particularly dangerous. ‘People walk to it, it has quite a gentle edge, but part of it falls into the estuary. At the shore there is soft mud, at the Ray it’s hard-packed sand, and one of its edges is a sheer eight-foot drop.’ In other words, someone could think they’re having a paddle, and drop straight in. It’s mainly ‘day trippers and people who don’t know about tidal estuaries,’ says Richard, who once rescued two ‘big lads in their twenties’ who fell in and the current took them out. You should, he says, always try and swim across the current, but ‘they tried to beat the tide’ - and nearly died.

There are other hazards, too: ‘a lot of time you’re standing on oyster shells’, then there’s boat wreckage, trawler wire which is used to hold the nets and ‘some just push it over the side, so we find coils of wire in the mud, as well as wartime debris, anti-aircraft shells, plane wrecks and once a pre-1900s cannonball. It’s not unknown for an angler to walk into the casino and say, “look! I found a mine”.’ Richard recently saw one ‘sitting on the mud the size of a smart car’ although a leak meant it was harmless. Those that still pose a threat are sometimes blown up on Ministry of Defence land at Shoebury.

Some people also attempt to jump off the pier and can be dragged under it by the current, where there are mussels, barnacles and shell-fish, in which case ‘you wouldn’t have much skin left,’ says Richard calmly, ‘and you will bleed because barnacles release an enzyme that stops blood from clotting’. Then there are sunbathers who ‘cook themselves’ all day in the sun, as well as having a few drinks, jump into cold water and suffer cardiac arrest. Traffic’s another danger; near the shore there is a speed limit for jet skis, but once they reach a quarter-mile out from the sea wall then it’s boat territory and ‘they go extremely fast’. There are also container ships, such as the one I saw earlier emerging from the North Sea, and boats doing thirty to forty knots ‘and no swimmer can outpace that’.

Richard is certainly putting me off having a swim around here, and recent reports from the Southend Lifeboat Station confirm the risks, with children found stranded on a sand dune with the flood tide coming in fast, and two people stuck in the mud underneath the pier head. Then there are the swimmers; a capsized catamaran had two people on board, ‘one of which had swum from Canvey Island to assist his buddy who he had just witnessed capsizing!’ There was ‘a possible person seen drifting west’ which turned out to be a white plastic container, a person suspected to be swimming from Canvey Island to Kent, although no one was found, and a swimmer thought to be in trouble offshore of Canvey Island who in fact was ‘a very good swimmer who takes to the water every day’.

The best time for a sensible swim, says Richard, is slack water and he goes into some detail about low and high tide, measurements and depth, and the role of the moon. I ask him if he feels the water outside these windows is a river or the sea. ‘I know it as a river, I can see the opposite banks, but a lot of people think it’s the sea,’ he laughs. ‘People think it’s Calais opposite. Actually it’s Snodland on the Isle of Grain, you can see the chimney.’ Then I ask him where the Thames ends. He points behind me, in the direction of the North Sea. ‘The Thames ends where it ends, when it becomes the sea, it ends.’ And when does it become the sea? He gets up a little wearily and traces a finger along a map on the wall. ‘I’ve been all round the coast and I feel you’re really at the end of the Thames there, once you’re around Wallasea. It feels like Clacton and Margate are still on the Thames, although they are not. Clacton to me is the absolute limit of the Thames.’

Richard is, of course, happy to negotiate with sensible swimmers, such as the organisers of the Great Pier Swim which began in 2008. But when he heard they wanted to swim from the pier head, his horrified reaction was, ‘ah no! You can’t swim the shipping channel, it’s one of the busiest in the world.’ Then when a local swimmer, Iain Keenan, got in touch, interested in setting up a swimming club in nearby Chalkwell, with a designated area and starting point for events, Richard thought, ‘right, OK, we’ve got a swim club, that’s better than a walking on the mud club’.

Having filled me with horror stories, Richard takes me to another room, as big as a warehouse, where the equipment is stored, including an amphibious boat which is used to rescue people from both mud and water. Finally, he bids me goodbye at the entrance to the pier, where I’m getting increasingly worried about the swim I’m doing this afternoon with the Chalkwell Redcaps Open Water Swimming Club. I fancied a pleasant dip; now all the way back to the railway station I have visions of stinging barnacles, lacerating oyster shells, zooming jet skis, lethal currents and buried wrecks.