Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

20

London Docklands

‘We loved everything about the river … it was our playground, our life’

John Daniel, Thames lighterman, 1950s

Downriver from Tower Bridge the River Thames now begins to enter London Docklands, once part of the Port of London and the world’s largest port, and an area where people have been swimming and bathing for at least a century, including in the docks themselves. In Roman and medieval times ships docked at small quays in the Pool of London, between London Bridge and Tower Bridge. Then, in 1696, the Howland Great Dock in Rotherhithe was built, providing a more secure place for large vessels. The Georgian era saw the opening of the West India Dock in 1802, followed by several others, while more docks were built in Victorian times, mainly further east, such as Royal Victoria and Millwall. Some were for ships to anchor and be loaded or unloaded; others were for ships to be repaired. ‘Lightermen’ on small barges carried the cargo between ships and quays, while quayside workers dealt with the goods onshore. In 1909 the PLA took over management of the docks, replacing a number of private companies, and built the last of the docks, the King George V, in 1921.

The docks suffered heavy bomb damage during the Second World War and while trade recovered in the 1950s they weren’t big enough to cope with larger vessels transporting cargo in containers, so they began to close. In 1981 the London Docklands Development Corporation was formed to redevelop the area, today a centre for business and luxury apartments. It’s also home to the Museum of London Docklands, on the side of West India Docks on the Isle of Dogs.

I arrive to find a grand old Georgian sugar warehouse, with spiked bars at the windows giving it a Bastille-like air, flanked by restaurants and bars, while down at the waterside an old boat is dwarfed by a huge glass building housing a bank. The Museum opened in 2003 and tells the history of the Thames and Docklands with twelve galleries spread over four floors. I walk around looking at artefacts, models and pictures, an atmospheric recreation of nineteenth-century riverside Wapping and a gallery explaining the city’s involvement in transatlantic slavery. But I can find little reference to swimming, except for a poster from 1870 announcing a fête at West India Dock.

‘The Thames, from London Bridge onwards, is a difficult and dangerous place to swim,’ says Tom Wareham, currently Curator of Community and Maritime History, ‘but people did. You weren’t supposed to bathe in the docks or the entrances to docks, but there is evidence that people drowned while bathing. Most drowned in winter when conditions were icy or smoggy, but there was also a peak in the summer. There was usually a beach, a stretch of silt, at the entrance to most docks, and kids were drawn to it.’

I follow him to a small meeting room where he’s arranged a number of documents on the table, including photocopies of Victorian ledgers written in beautiful cursive script and modern colour-coded bar charts. Such was the concern at the number of fatalities in the late nineteenth century that the docks committee ordered an investigation. An unnamed clerk looked at fatality reports from four sample periods between November 1873 and December 1891. The results were alarming: nearly three people drowned every month - 176 deaths over a seventy-one-month period. This was despite the fact that the various private dock companies encouraged their employees to learn to swim, and even offered lessons in an outdoor tank at the West India Docks.

Of the known causes of death, five boys drowned while bathing. But far more fell from barges and ships; one boy was knocked into the water by a rope, a stevedore missed his footing coming ashore, a ship keeper slipped off a gangway ladder. Records from the winters of 1873-4 and 1879-80 show that most drownings happened at West India Dock, which was one of the biggest areas of water with a large number of people living close by.

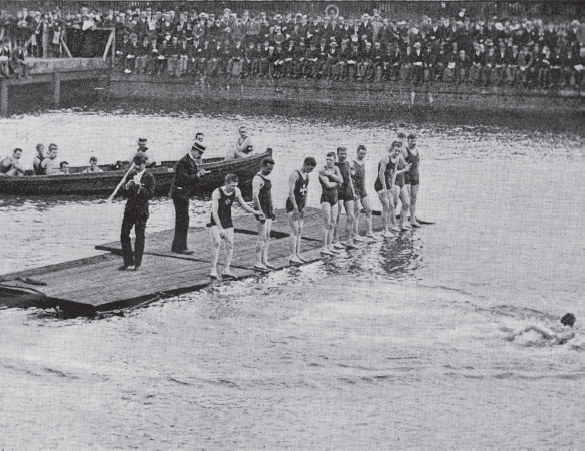

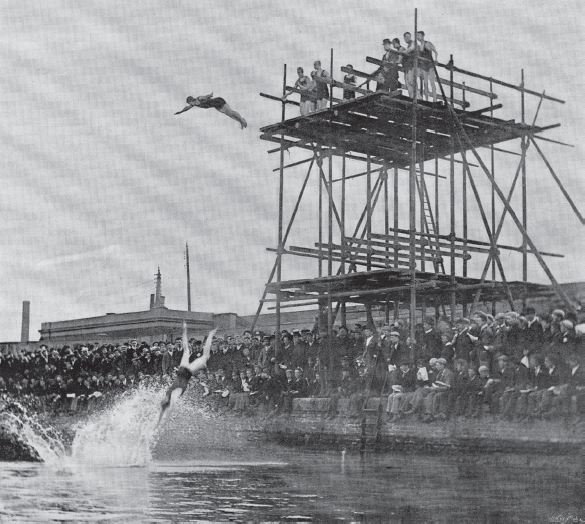

In the early 1900s police paid young boys half a crown for every body they retrieved from the Pool of London, with many deaths the result of swimming under a boat and getting trapped. But soon amateur swimmers were racing in the docks and newspaper photographs from 1895 illustrating ‘A Swimming Fete at the Docks’ show nine bathers, all apparently men, about to leap off a floating wooden board on which stand two suited officials. One swimmer is already in the water; behind the raft is a rowing boat full of people, while the sides of the dock are dense with spectators. Another image catches two divers in midair, having just thrown themselves off a temporary diving stage.

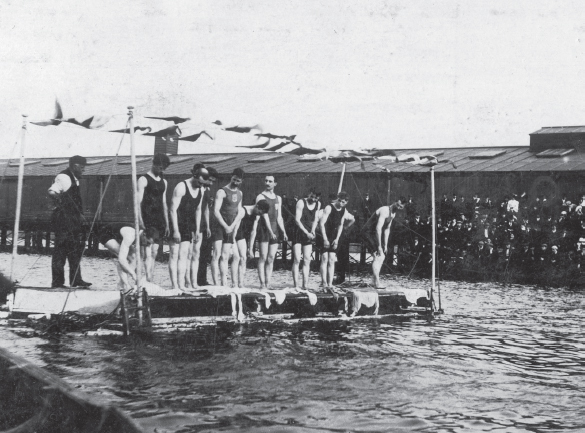

In 1906 the London and India Docks Swimming Club held their gala at Millwall Cutting, and again pictures show a row of men about to dive off a raft, although this time it seems to be covered in clothing as part of the ‘50 yards wet shirt handicap’, with corner poles holding up bunting. By the early 1930s the docks had become the setting for swimming events run under ASA rules. The Port of London Authority Swimming Club had an annual open-air gala at the Millwall Cutting, starting at 3.15 in the afternoon, complete with printed programmes costing threepence. The Daily Mirror featured a front-page photo of ‘Dock as Swimming Bath’ showing the fifty yards championships at the PLA’s swimming gala at the Millwall Cutting. The dock looks vast, like a lido, with concrete sides and a group of officials at one end, all set against a grey background of warehouses, bridges and ships’ funnels.

‘A Swimming Fete at the Docks’. It’s not clear which dock this is, but the date is July 1895.

I’m surprised the Docklands Museum hasn’t anything much to commemorate these old events, until Tom tells me they have three silver cups (not on display), won by Kathleen Ralphs (née Elgar) in the PLA Swimming Club Ladies Championships between 1932 and 1934. They also have a transcript of an oral recording of her memories.

Ralphs was born in 1913; her father was in the navy and his father worked as a granary foreman in the old Surrey Docks. When she was seventeen she joined the PLA as a typist. ‘The social life was wonderful,’ she recalled, ‘the main thing I can remember is the swimming club they used to have [and] swimming galas there in the West India Dock.’ She belonged to the Lewisham Ladies Swimming Club, separate from the PLA but which was invited to take part in the galas. The day before an event a section of the dock was ‘skimmed off’ and a boom put across the entrance so ‘nothing else could float in’. The dock was decorated with bunting, there were tugs to undress in and 40 feet of water to swim in. ‘I used to love swimming in the dock,’ she remembered, ‘because although it had been skimmed it was still very oily and it made you feel tremendous. You just shot through the water at twice your normal speed.’ The river had a distinct odour: ‘it wasn’t a dirty smell but it was a certain smell when the wind blew in our direction’ and her mother was ‘always waiting with a dose of sennapods’ (the seed of the senna plant used as a purgative) when she got home from a swim, because ‘she said, “you don’t know what you might have swallowed”’.

As a child Ralphs’ father also used to swim in the docks, where one swimmer was ‘a very good swallow diver’ and later ran a club for local boys. Ralphs’ father had a silver medallion for life saving and she had bronze. ‘I always used to think now I’ve got this medallion and I must make use of it. So I was just dying for someone to fall in the dock so that I could rescue them.’ Everyone working for the PLA had to swim. ‘In those days swimming was a pastime that everyone indulged in … everybody swam as a matter of course.’

People continued to swim in this area of the Thames after the war, and Tom has someone he wants me to meet. Downstairs at the entrance to the Mudlarks Children’s Gallery is Museum guide Brian Gover, wearing the distinctive bright pink shirt required of employees, which he’s not overly fond of. He opens the gallery door and children rush in to the interactive play area, some heading for the sand bowl, others for the water area or the model ship.

Brian makes sure they’re settled, before telling me of his swimming experiences. He was born on the Isle of Dogs in 1941 and remembers two areas where you could swim officially, Tower Bridge and Greenwich. ‘It was strange really, we were allowed to swim but if a worker on the river fell in he spent three days in hospital under observation. But we grew up in post-war London and our playground was the Thames. You could find so many things on the river. If you needed a new rabbit hutch then you could pick up timber, and we used to raid the barges for peanuts.’

Dives in progress during a dock swimming fête in 1895.

Some children dived from barges or from the steps off the causeway; others just waded into the water. ‘No one had swimming costumes,’ says Brian, ‘or if you did then you were lucky. Mums knitted them and once they were wet they hung by your knees, so people didn’t bother wearing them.’ He remembers only boys playing in the Thames and ‘we would wave at American tourists on the pleasure boats and they would throw us money’. But everyone knew it was potentially dangerous. ‘We were warned not to swim, the police would come around the schools and tell us not to. But the river was the only place to play. The barges moved up and down, bobbing in the water, and a lot of children died from jumping off them or getting stuck underneath.’

As for the water, ‘it was absolutely filthy and full of oil, we all had boils. It was polluted, no doubt about it. There was a lot of glass and you cut your feet. The older lads went to the Thames with air guns to shoot the rats. You’d see a cow going up and then the tide changed and you saw it come back again … twice the size! You also saw dogs, cats, trees, horses … and boats chucked everything, all the waste, overboard.’ As he got older, ‘we just grew out of it, and they shut up the stairs and built up behind them. The stairs were for ships mooring, there were jetties for the seamen to walk up and we used them, there were no barriers then.’

John Daniel, who worked as a Thames lighterman in the 1950s, also experienced the dangers of the river, as recorded by his son, Peter, who is educational officer at the City of Westminster Archives. Daniel’s family worked on the Thames in one form or another for many generations. ‘We loved everything about the river … it was our playground, our life.’ In 1953, at the age of fifteen, Daniel left school and got a job on a Thames sludge boat; he was then apprenticed as a Thames lighterman with Humphrey and Grey Ltd, based at Hays Wharf and at one point employing more than 200 men, with seven tugs and 400 barges. As the weeks progressed Daniel learned the skills of a waterman, using the natural currents of the Thames. The river then was ‘completely different. There were so many craft afloat, so many barges that you could almost walk across some of the docks by stepping from one to another.’

The river shaped Daniel’s life and he met his future wife thanks to the Thames. One day he was with a friend who’d invited ‘a lovely redhead named Pat… to join us for a day’s sailing at Greenwich’. But as Pat was about to ‘step into the dinghy to take her ashore she slipped and found herself waist-deep in the water. I gallantly fished her out … Forty-six years, four children and five grandchildren later I think that was the best day’s work I ever did on the grand old river.’

This stretch of the Thames still draws swimmers, like journalist and former Conservative politician Matthew Parris who in 2010 decided to cross the river a little way upstream from the Museum of London Docklands - and got into quite a bit of trouble. Matthew had never swum in the Thames before, although he did once rescue a dog, ‘but that doesn’t count as a swim’. The rescue took place on a late February night in 1978 when he was walking home after work from Westminster. ‘I saw a little boy and girl near the river and they were crying. They said they’d taken their dog out for a walk and it had climbed over the parapet and fallen in. It was dark, the tide was high and it was windy. I was brought up in Africa; I didn’t know how cold it really was.’ But he plunged in and saved the dog, and a few months later was awarded an RSPCA certificate for bravery, presented by then leader of the opposition, Margaret Thatcher, on Westminster Bridge.

In July 1906 the London and India Docks Swimming Club held their gala at Millwall Cutting, including the 50 yards wet-shirt handicap.

Some thirty years later Matthew took his first planned swim in the Thames, although it was something he’d been mulling over for fifteen years. His decision was inspired by the part of London in which he lives, on Narrow Street in the East End. ‘I look across to the Globe Stairs,’ he explains, ‘and I wanted to swim across the river. People didn’t believe me, I was always boasting about doing it. They said, “take a life jacket, have someone in a boat, tow a life belt”, but to take the means to save you, well, that’s cheating. I didn’t think it was risky, and I don’t think so now. There was no traffic, only the occasional barge. You can see up both arms of the river for around half a mile, and I wasn’t doing it alone.’

Matthew, who describes himself as no great swimmer, decided to make his crossing in high summer when the water was warmest, and at high tide as it turned. He would start from the stairs at Globe Wharf and swim straight across to the Ratcliffe Cross Stairs at Narrow Street. His lodger, Tom Mitchelson, would flash a light from the balcony to show the coast was clear, and when Jonathan Weir, a twenty-year-old student, heard Matthew wouldn’t be taking a life jacket he said he would come, too. One night they finally put their plan into action. Matthew had checked online tide tables; he would go at slack tide (the period before the tide changes direction), at 03.35 on Thursday morning. So he had a few hours’ sleep, put on trunks and an old singlet and some discardable flip-flops and then just after 3 a.m. called a minicab to get to the other side of the Thames under the Rotherhithe Tunnel. Along with Jonathan he crept down the Globe Stairs and undressed. A barge slid past, a light from the balcony light flashed and in they jumped. The water was choppy but Matthew, swimming breaststroke, couldn’t feel any current. ‘It wasn’t cold, it was very different from 1978, but the waves seem higher when you’re in it, you feel them slap against your face.’ Then, when he turned to look for the Globe Stairs behind him, he saw they were far over to his right; the two men were being carried speedily upstream.

They decided to stay close together and keep swimming towards the opposite bank but without fighting the current. Soon they were almost past the King Edward VII Park, and approaching some moored sailing boats at Wapping, when Jonathan managed to grab a rope and Matthew a rudder. They then reached the stilts of a riverside boardwalk, pulled round to a little creek, and climbed a ladder on to a road. ‘I would have carried on if I hadn’t managed to get out at Wapping,’ says Matthew, ‘there are big warehouses so the next place I would have been able to get out would have been another mile or so.’

They’d been in the Thames for around half an hour, and they were about three-quarters of a mile upriver from Limehouse. Barefoot, wet and freezing, the two men ‘ran down the highway’ for home, with Matthew’s underpants full of mud. Tom, still waiting at the flat, told them, ‘I reckoned you’d either drowned or you hadn’t, there was no point calling the police. Anyway, I had the strongest of hunches you’d be OK.’ It was then that Matthew realised navigational tables are in GMT. He’d got the time wrong; high tide was an hour later than he’d thought. Yet he was overjoyed that he’d done what he’d set out to do and, as for any effect on his health, ‘I did swallow a lot of water and it tasted slightly salty which was a surprise, but both of us were fine.’

Matthew got plenty of press coverage, mainly because he wrote about his swim in The Times, and also because of people’s response. He began his article with, ‘First, don’t try this at home. It could have ended in disaster. It was ignorant and it was dangerous. But it was not impetuous.’ Today he says, ‘I knew people would condemn me, I was not surprised by people saying it was dangerous, but I didn’t think it would get so much reaction, I just thought it would raise a few eyebrows.’

And what does he think of the new by-law that would now make his swim illegal? ‘Stupid. There are millions of places in Britain where it would be dangerous and they can’t prohibit swimming in them all, it’s your own decision.’ As for the PLA’s argument that a swimmer poses a danger to boats, he says, ‘mostly it is dangerous in the Thames, but any object could pose a potential hazard to boats, there are all sorts of things in the river like huge logs. It could be a hazard if a boat swerves to avoid you, but that’s far-fetched.’

The reaction to his article was mixed. Explorer Bear Grylls said he’d once swum in the Thames towing a canoe on a long line; he’d ended up one mile downstream and wouldn’t do it again. Photographer Brian Griffin said it was ‘an absolutely crazy thing to do … I’ve seen the stuff that is dumped in it, and what is washed up on the beach. I’ve seen bodies, I’ve seen the whole lot.’ But as with Victorian swimmers, Matthew was also applauded for his daring. Playwright Steven Berkoff, who swam at the Tower Bridge beach as a child, called it an ‘audacious, dazzling, daring piece of derring-do’. Kate Rew, founder of the Outdoor Swimming Club, praised Parris’ sense of adventure, while politician Vince Cable admired Parris’ ‘pluck’. However, he added that considering the Thames ‘takes sewage from overflowing storage tanks and acts as home to various microbiological nasties, I shall stick to boats’. At the time Matthew said he would never do it again, but would he? ‘I think I may,’ he says, ‘especially as it’s illegal now. But I won’t write about it. And I’ll get the tide right this time.’