Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

15

Battersea-Lambeth

‘I seek not to wander by Tyber or Arno,

Or castle-crown’d rivers in far Germanie;

To me, Oh, far dearer,

And brighter, and clearer,

The Thames as it rimples at fair Battersea’

Excerpt from a song published in

Bentley’s Miscellany, 1839

Some three miles downstream from Putney, on the south side of the river and heading towards central London, is the inner city district of Battersea. While the recent by-law means people can’t in theory swim around here, it was a popular place for bathers and racers from at least the 1600s. Back then, when the river was generally considered clean, Charles II and his brother James enjoyed many an evening dip ‘to bathe themselves’ around Battersea, Putney and Nine Elms. King Charles was certainly a river lover, with ‘a propensity for swimming in the Thames at 5.00am at all seasons,’ writes his biographer Antonia Fraser, plunging into its freezing waters while ‘his courtiers shivered on the bank’. He was also said to have established contests on the Thames, when it was common for members of the aristocracy to sponsor working men to swim for a wager.

Swimming and ‘foot races’ became fashionable in England during his reign, explains The Badminton Library, and when Colonel Blood was arrested in 1672 for stealing the Crown Jewels at the Tower he confessed he ‘had engaged’ to shoot His Majesty as he went to swim in the Thames above Battersea. However, as Colonel Blood was about to take aim, ‘the awe of majesty paralyzed his hand’ and he changed his mind.

One of the earliest Thames races reported by the press took place at Battersea, some 150 years later, when in August 1826 ‘a party of printers took an aquatic excursion up the river’ in order to decide a wager ‘between them and a gentleman of some sporting celebrity’. The course was from Battersea Bridge to Blackfriars, four and a half miles with the tide without stopping, which another swimmer had successfully managed a few weeks earlier for a twenty-guinea bet. In this case a Mr Jolley, ‘champion of the Typos’, managed the swim in one hour thirty-five minutes, accompanied by pleasure boats and a band that played ‘See, the Conquering Hero Comes!’ as he got to Blackfriars - a tune that it would become standard practice to play for future long-distance Thames swimmers. The tide must have added to Jolley’s speed considerably, as he appears to have been doing a mile in twenty-three minutes, while he ‘only turned himself on his back for 40 yards’ twice during the whole time.

It’s a bleak morning in early May and everything looks dull when I get off a bus at Battersea Bridge. I’m intending to walk a little way upstream from here to try and find the site of a swimming match held in 1838. The road, the pavements and even the sky are grey, while ahead of me the row of Victorian street lamps that line the bridge look suitably gloomy.

The original bridge was a wooden construction, completed in 1771, and by Victorian times it was the scene of many boating accidents. In one incident in the 1870s three young men were rowing upriver and when one stood up under the bridge to haul in his oar the boat capsized. The bridge was crowded with pedestrians and the cries for help soon reached the Thames Police. All three men survived; as usual, none of them could swim.

The job of the Thames Police, formed in 1798 and described as England’s oldest police force, was to protect property in the ships, barges and wharves within London, to ‘keep the river clear of reputed thieves and suspected persons’ and to rescue those in trouble. The Victorian press often reported on ‘terrible discoveries in the Thames’, such as the day the police found a ‘set of lungs’ floating under Battersea Bridge, and twelve hours later another set at the railway pier. In 1873 the Thames Police saved 32 people from drowning, and ‘prevented’ six suicides. In total there were 150 deaths in the Thames that year, four times the number there are today: 25 were suicides, 79 were accidentally drowned, 4 were from accidents. In the remaining forty-two cases it wasn’t clear how the person came to be in the river and they were therefore classed as ‘found drowned’.

As I leave Battersea Bridge and walk right along the river I pass a series of moored houseboats and a sign warning ‘Private Property’. Between the boats and the road there is a beach of sorts, its surface a slimy green; a group of ducks huddle on a pile of twigs, bottles and plastic bags. I’m heading to Cremorne Gardens where one of the first recorded swimming races on the Thames was held, between pupils of the recently formed National Swimming Society ‘and others’ for silver cups and snuff boxes during an exhibition match from Cremorne House Stadium to Battersea and back to Chelsea.

In 1831 Cremorne House, the former residence of Lord and Lady Cremorne, had been bought by Charles Random, also known as Baron De Berenger. He turned part of it into a sports club and his plans for ‘The Stadium’ or ‘British National Arena’ included a six-day Olympic Games, with one day devoted to ‘feats in swimming and other aquatic exertions’. The twenty-four-acre site would be a place for ‘manly and defensive exercises, equestrian, chivalric and aquatic games and skilful and amusing pastimes’. The art of swimming, wrote Random, was ‘so much neglected, although so truly an important acquirement to persons in all spheres of life’. Lessons would be offered, ‘aided by novel contrivances’, but only early in the morning in order not to offend ‘decency’, as presumably the pupils were naked. There was a 4-foot-deep ornamental lake, which would serve as a School of Natation for young beginners, and ‘The Honourable the Thames Navigation Committee’ had recently granted ‘the extraordinary privilege to the Proprietor of the Stadium, of constructing a floating swimming school of large dimensions, with permission to moor the same in the river’.

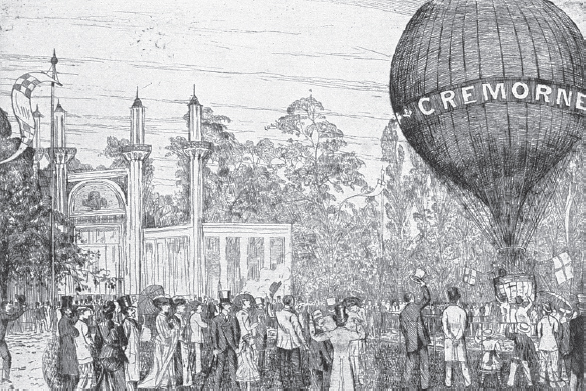

A balloon ascent at Cremorne Gardens depicted by Walter Greaves in 1872. The twelve-acre pleasure gardens opened in the 1840s, before this it was the site of a sports stadium, which boasted a school of natation and where races were held across the Thames.

This certainly sounds an organised way of promoting the art of swimming. As with the opening event of the first National Olympian Games at Teddington Lock in 1866, the Thames was seen as the ideal spot for some ‘manly exercise’ in a city that was now home to numerous sporting clubs, societies and associations. During the 1838 race, the two heats ‘started with the discharge of artillery’, then at half past three swimmers wearing different coloured jockey caps and flannel drawers ran out of tents on the riverbank and ‘plunged into the bosom of father Thames’. It appears to have become a regular event. In 1840 the Morning Herald announced, ‘SPORTING NOVELTIES. A SWIMMING RACE twice across the Thames by AQUATIC JOCKEYS will take place at Cremorne house, King’s Road, THIS DAY’. The Town ran a colourful description of the scene: ‘Upon entering the grounds, we observed a number of faces familiar to us, amongst which were the Duke of Dorset, the most noble the Marquis of Waterford, Lord Waldegrave, Count D’Orsay … “Here come the jocks!” saluted our ears … We turned round and beheld a file of stark naked adults, marching round the grounds, in order to show themselves’ before diving into the Thames. A moment later and ‘a multitude were unrobed. The Duke of Dorset was the first to fall into the line. His Grace’s skin had a shrivelled, yet very glossy appearance.’

Despite aristocratic enthusiasts eager to prove themselves in the Thames, Random’s grand plans were not to be and a few years later the Stadium closed. Cremorne then became one of several pleasure gardens along this stretch of the river, offering concerts, fireworks, balloon ascents and galas. The Thames was now a place for entertainment and carnival, as it would be a little later on the upper river. The artist James Whistler moved to Lindsey Row in Chelsea in 1863 and his windows faced the Thames which he painted over forty years, whether the exposed piers of Battersea Bridge at low tide or fireworks at Cremorne Gardens. But for bathers in this area the river could be dangerous. In the summer of 1857 a sixteen-year-old boy died while bathing near Cremorne Gardens when he fell into ‘one of the mud-holes’ with which ‘the river is intersected’.

A bright blue sign announces I’ve arrived at the Gardens, a tiny park with cobbled stones and benches. On the right is a set of big black gates, ornately decorated with flashes of gold, which open on to a small patch of grass. I walk towards the river, to a pier and iron railings. In front of me is a large red ‘No Swimming’ sign. The shore below is covered in pebbles and rocks; water has collected in a big dirty puddle. I knock on the door of the park keeper’s office and ask if this used to be the Victorian pleasure gardens. ‘Pleasure gardens?’ replies the park keeper. ‘I’ve no idea.’ He comes outside and looks around. ‘Although someone once told me their great-great-grandfather used to come here and there was a wire across the river and they used to walk across it.’ And does he ever see anyone swimming here now? ‘No,’ he says, ‘though we did see David Walliams go past. We were saying, “is it him or is it a seal?”’ Aside from naked races in Victorian times and the swimming school outlined by Random, Battersea was also the location for a proposed floating bath, a precursor to various pontoons along the Thames such as the one at Kingston in 1882. ‘The want of proper accommodation for bathers and swimmers in the Thames has long been felt,’ explained the press. But now a limited company had been formed, with a capital of £60,000, ‘for the purpose of constructing floating baths on rivers and lakes, with filtered water of uniform depth and temperature’. This would begin with ‘a covered and well-ventilated iron bath, to be placed in the Thames off Battersea Park’. Lloyd’s Weekly reported in 1870 that there would be a 60×40 feet bath, but it’s not clear if this ever happened because it wasn’t until 1875 that the ‘first floating bath’ on the Thames was announced and that was at Charing Cross, off the Embankment, while the following year another was proposed near Albert Bridge.

There is little in the way of any modern swims or races recorded at Battersea, although in the early 1950s local children often enjoyed jumping from the bridge. One remembers ‘street urchins, myself included, jumping from the first arch’ into the river. They then ‘swam to the adjoining steps, ran along the warm pavements back on to the bridge, and jumped off again’. Bridge jumping appears to have been quite common in the 1950s. Londoner Alan Smith told his children he had been the youngest person ever to dive off Hammersmith Bridge, upstream from here, in 1952. ‘He was fifteen years old and he was in a diving squad of some kind,’ says his daughter Stephanie, and when he died the family scattered his ashes on the river he loved so much that he always called it ‘Old Father Thames’.

Bridge jumping was once quite common in central London; as late as the 1950s local children enjoyed jumping from Battersea Bridge. Here two divers leap off the Embankment near Westminster Bridge in May 1934.

More recently, Battersea was where politician John Prescott set off for a swim in 1983 to protest against the government policy of dumping nuclear waste at sea. He’d agreed to take part in a National Union of Seamen and Greenpeace demonstration to attract attention to the issue. His mission was to swim two miles from Battersea Bridge to the House of Commons in ‘frogman’s gear’ with a mask, oxygen and wetsuit. John liked the notion of a long swim - ‘it reminded me of Chairman Mao swimming down the Yangtze’ - but didn’t fancy the water: ‘one gulp of the Thames and you’d be a goner’. Appearing on TV-am shortly before his swim, he said he hoped it would be ‘over quick’. His plan was to wait until the tide had gone out ‘with the rest of the crap’ and then set off. A congratulatory telegram from comedian Spike Milligan advised him to have a typhoid shot.

Originally, John wanted to climb out of the water at the Palace of Westminster, go up the steps on to the House of Commons terrace and deliver a petition to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at No. 10. But he wasn’t allowed to land at the House and was told the steps couldn’t be used ‘for a political purpose’. He argued that if he was refused landing rights he might be in danger, quite apart from the danger he might already be in from the polluted river. It was finally agreed he could arrive at the steps, but couldn’t walk up them to Parliament. Instead he’d step into a boat and then move off again.

John completed the swim in ‘about an hour’ on a freezing cold December day, accompanied by demonstrators in boats. He climbed out at the steps of Parliament, got in a boat and went to a landing stage at Westminster Bridge where he walked to Downing Street, still in his swimming gear. Greenpeace demonstrators ‘had been planning to use me as a Trojan horse,’ he later wrote, ‘to get into the Palace of Westminster’, by following him up the steps. A few weeks later, they took another route by climbing the clock tower of Big Ben.

The only other swim at Battersea to have received any coverage in recent years was that of a five-metre-long Northern bottlenose whale. It was spotted on 19 January 2006, having swum through the Thames Barrier, the first time the species had been seen in the Thames since records began in 1913. The following day it was seen at Battersea and then, near Albert Bridge, it was captured and lifted into a barge, but died before it could be returned to the sea.

The tradition of swimming around Battersea seems to have been lost in recent decades and while it was once a place of manly exercise and amusing pastimes with a school of natation for beginners, there are no plans to introduce swimming events as has happened further upstream. Perhaps the river here is perceived as just too dirty and crowded, quite apart from the ‘No Swimming’ sign and the 2012 ‘ban’.

I leave Cremorne Gardens and walk back along the Thames on my way to Chelsea and then Lambeth bridges. The sun is coming out and Battersea Bridge looks more inviting now; a cherry tree is heavy with blossom, golden inlays on the side of the bridge glisten and soon I come to Albert Bridge with its silver towers and pink-panelled sides, its unusual colour scheme chosen in order to make it more visible to ships during heavy fog. There are plenty of boats moored in the middle of the river, while on the roadside are regular danger signs warning of strong currents. On the opposite side is Battersea Park, once the proposed site of a floating bath.

When I get to Chelsea Bridge, nearly a mile downstream, the entrance is blocked by builders and a small forklift truck; on the southern side loom the chimneys of Battersea Power Station. The original bridge opened in 1858, with four cast-iron towers topped with lamps that were to be lit only when Queen Victoria was staying in London. Long before the bridge was built, in the mid-1600s, Sir Dudley North, civil servant and economist, was known for his swims around here. He was an intrepid swimmer and a ‘master of the Thames’ who could ‘live in the water an afternoon with such ease as others walk upon land’. He would leave his clothes on the shore, run naked ‘almost as high as Chelsea’ for the ‘pleasure of swimming down to his clothes before tide of flood’, gliding along with the current like an arrow, dodging anchors, ‘broken piles and great stones’.

Chelsea was also where two well-known eighteenth-century figures chose to swim. ‘I am cruel thirsty this hot weather,’ wrote Jonathan Swift to his friend Esther Johnson in June 1711, ‘I am just this minute going to swim.’ He presumably went naked, as he had someone ‘hold my night gown, shirt, and slippers’ and borrowed a napkin from his landlady ‘for a cap’. He assured Johnson, ‘There’s no danger, don’t be frighted. I have been swimming this half hour and more; and when I was coming out I dived, to make my head and all through wet, like a cold bath; but as I dived, the napkin fell off and is lost, and I have that to pay for.’ He also had trouble with ‘the great stones’ which were so sharp that as he came out of the Thames he could hardly set his feet on them. The next night it was back for a dip again, but with ‘much vexation … for I was every moment disturbed by boats, rot them … the only comfort I proposed here in hot weather is gone; for this is no jesting with these boats after ’tis dark … I dived to dip my head, and held my cap with both my hands, for fear of losing it. - Pox take the boats! Amen.’

Benjamin Franklin, who would become one of the ‘founding fathers’ of the United States of America, also swam at Chelsea. During a stay in England in 1726 he showed off his swimming skills on a Thames excursion with friends: ‘At the request of the company, I stripped and leaped in the river, and swam from near Chelsea to Blackfriars (3½ miles) performing on the way many feats of activity, both upon and under water, that surprised and pleased those to whom they were novelties.’ One report has him demonstrating overarm, breaststroke, backstroke and then overarm again as people, clearly surprised and impressed in a city where few could swim, stopped to watch.

Franklin, who grew up near the sea in Boston, had been swimming since a child and had ‘been ever delighted with this exercise’. While in England he taught two friends to swim in the Thames and, before returning to America, he considered opening a swimming school, much like Random a hundred years later. In 1968 Franklin was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame, which describes him as ‘one of our first marathon and ornamental “synchronized” swimmers’.

So, well before Eton College had its seven bathing places along the river, Sir Dudley North was running naked along the Thames near Chelsea in order to swim back to his clothes, Jonathan Swift was taking a dip to escape the heat and Benjamin Franklin was showing off and inspiring others with his skills. The tradition of Thames swimming appears to be even older within the city than it is in the clear reaches of the upper river.

By Victorian times Franklin’s skills would have seemed a little less remarkable, although life saving was still in its infancy and the Royal Humane Society frequently handed out medals for those brave enough to try and save another’s life. In 1882 Bram Stoker of subsequent Dracula fame, then in his mid-thirties, was awarded a bronze medal for attempting to save a man in the Thames. On 14 September, at about six in the evening near Chelsea, a man aged between sixty and seventy and presumed to be a soldier, jumped into the river from the steamboat Twilight. Stoker, who was on the same boat, travelling to London Bridge and perhaps on his way to the Lyceum Theatre where he was acting manager, threw off his coat and jumped overboard. After ‘grappling’ with the man for five minutes, both were hauled back on to the boat and Stoker carried the man to 27 Cheyne Walk where his brother, Dr George Stoker, was unable to revive him. Bram was rewarded for his ‘gallant attempt’ and went on to create several fictional characters who would successfully rescue people from drowning.

By now there was an opportunity for more people to swim in the Thames, around a mile downstream from Chelsea Bridge, near Vauxhall Bridge. These were Pimlico floating baths, established by the Floating Swimming Bath Company, with plans showing a glorious front elevation like a huge conservatory. The Board of Trade approved the idea towards the end of 1873 and the bath would be moored off Grosvenor Road, at the end of Ranelagh Road. However, press reports say the 260×47-foot pool was erected opposite Pimlico Pier.

It’s not easy, walking parallel with the Thames along Grosvenor Road today, to find where the baths might have been. At the end of St George’s Square Garden there is still a pier, then comes Pimlico Gardens and the Westminster Boating Base. But past this there is no access to the river - which is blocked by a petrol station, flats and office buildings. I stand on tiptoe at the end of Claverton Road and peer over the stone wall at the choppy waters of the Thames. The sound of traffic behind me on Grosvenor Road is never-ending, while on the river there is nothing moving at all. Where would the floating bath have been, was it ever built and, if so, did people use it?

I walk on to Vauxhall Bridge, the first cast-iron bridge over the Thames, where the air is noisy with the clanging of builders’ cranes. Below street level the bridge is colourful, a riot of orange, red and blue, with large bronze figures gazing out over the water. It was here in the mid-1800s that there were charges of ‘indecent’ bathing upsetting steamboat passengers and where a clown called Mr Barry set sail in a washtub pulled by geese all the way to Westminster Bridge.

I head next to Lambeth Bridge, around three-quarters of a mile downstream and the ‘ugliest ever built’ according to Dickens’s Dictionary of the Thames, where Lord Byron enjoyed a lengthy swim in 1807. On 11 August, the nineteen-year-old wrote to Elizabeth Pigot that he was about to set off for the Highlands. He would hire a boat and visit the Hebrides and then, if the weather were good, set sail to Iceland. ‘Last week I swam in the Thames from Lambeth through the 2 Bridges Westminster & Blackfriars, a distance including the different turns & tacks made on the way, of 3 miles!! You see I am in excellent training in case of a squall at Sea.’ Byron must have swum more than once in the Thames, for the poet James Leigh Hunt remembered first seeing him in the river sometime around 1809: ‘There used to be a bathing-machine stationed on the eastern side of Westminster Bridge; and I had been bathing, and was standing on this machine adjusting my clothes, when I noticed a respectable-looking manly person, who was eyeing something at a distance.’ This was Mr Jackson, a prize fighter, waiting for his pupil, Byron, who was swimming against somebody ‘for a wager’.

If Byron sounded boastful in his letter to Pigot, he would soon have reason to be and today his epic swims are almost as enduring as his poetry. Three years after his swim from Lambeth he crossed the Hellespont, on his second attempt, inspired by the Greek myth of Hero and Leander, covering four miles in one hour ten minutes. Leander drowned one evening while swimming across the Hellespont to visit his lover, Hero, a journey he made every night. He ‘swum for love, as I for glory,’ wrote Byron in ‘Written After Swimming from Sestos to Abydos’.

Later he swam from the Lido in Venice ‘right to the end of the Grand Canal, including its whole length’. Byron was inducted as an Honour Swimmer by the International Marathon Swimming Hall of Fame in 1982 and is considered one of the earliest pioneers of open-water swimming. The 1828 Book of the Society of Psychrolutes at Eton contains a calendar with notable dates in the history of swimming, including the birth of Lord Byron, ‘the first poet and first swimmer of his age’. Born with a contracted Achilles tendon, ‘Swimming gave him some of the most exhilarating moments of his life,’ writes Charles Sprawson, ‘though he always wore trousers to conceal his disfigurement. Only in swimming could he experience complete freedom of movement, the principal to which he devoted his life.’

I stand on Lambeth Bridge, no longer the ‘ugliest ever built’ but today painted bright red in parts, the same colour as the seats in the House of Lords. Downstream the view is impressive, with the towers of Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament, and I think about the waterway below me and the stories it carries with it. This really is, as former MP John Burns declared in 1929, ‘liquid history’; where naked aquatic jockeys, poets and politicians all stripped off to immerse themselves. When Benjamin Franklin took to the river in 1726 he would hardly have had the option of an indoor pool, and nor did Byron in the early 1800s, aside from a couple of London ‘Pleasure Baths’. But even if warm indoor baths had been readily available, both would still no doubt have preferred the glorious wild openness of the River Thames.