Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

14

The Port of London Authority

‘A person must not without the prior permission of the PLA, given in writing, and in accordance with such conditions as the PLA may attach to any such permission: swim (with or without a flotation device) in the Thames anywhere between Crossness and Putney Bridge’

2012 by-law

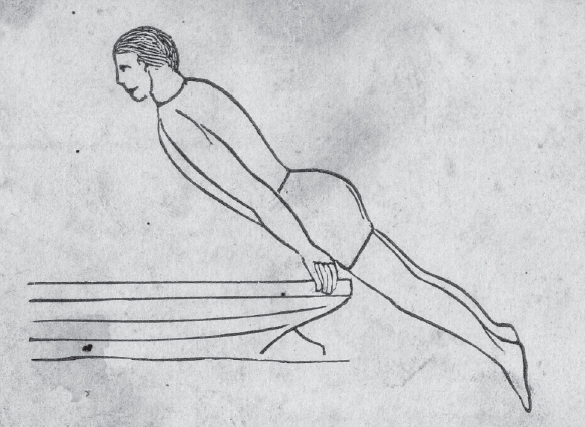

Instructions from Professor Bocockon the best way for a swimmer to leave and enter a boat.

The by-law that governs swimming from Putney down to the Thames Barrier was introduced in 2012, but well before this there had been heated discussions between the PLA and those intent on swimming through central London. In 2005, for example, Andy Nation originally planned to swim from the source to Southend but was told to stop at Teddington. ‘Out of courtesy I had told the PLA about my swim and they said, no, I couldn’t swim through London,’ he explains. ‘I got out the book of Thames by-laws and said, “can you tell me where it says I can’t swim through London?” They said, “we can’t but we can make it very difficult for you”, and they did.’ Andy says the charity he was raising money for asked him just to do the non-tidal Thames, after being approached by the PLA.

The following year, when Lewis Pugh similarly intended to swim from source to sea, ‘he rang me up about his swim and asked what I’d done about the PLA. I said I’d wanted to give them the finger but because of the pressure they put on the charity I’d had to get out at Teddington. The PLA are scared of their own shadow. They control the water and they think they can stop any activity. It’s not in the spirit of what adventure and pushing the boundaries of human endeavour is about. As long as you do it responsibly and safely then they should do everything they can do to assist you.’

Lewis Pugh, meanwhile, says he was told that under no circumstances could he swim beyond Teddington during his 2006 journey along the length of the Thames, as it was too dangerous. ‘When I met with the PLA I explained that I’d safely swum in significantly more dangerous parts of the world including the Arctic and Antarctica. The PLA said if I attempted it a number of things were going to happen. One, a ship could try to avoid me and run aground, two, it could hit me, three, there were strong currents which would pull me under. They said, even if I made it, it would encourage people less able than me to do it and they would drown. I explained I wouldn’t be swimming anywhere near any shipping, I’d be swimming along the edge of the river and I would have a safety boat next to me. They would not budge. To me they were being silly and not even considering the merits of the case.’

Lewis then walked out of the PLA’s office, ‘determined to go to the source and start to swim. There was an important principle, which I felt strongly about. To me this was a human rights issue. Surely rivers are natural resources. They are part of our common heritage; it’s not right to say to people you can only use the river if you own a boat, but not if you don’t. Every Briton should be entitled to swim down our rivers to our heart’s content - providing we do so safely. Throughout the swim I received calls and emails from the PLA saying they would arrest me if I swam past Teddington. I ignored them. There was no specific law preventing me from swimming down the tidal section of the Thames. However, I began to worry about the issue as I neared London. They would surely have a residual Common Law right to pull me out, if I was deemed a danger, and being a maritime lawyer if I got arrested it wouldn’t look good for either side.’ Lewis says he then had a phone call from Downing Street: ‘the Prime Minister said “please get out at Westminster and come and chat with me. I want to discuss climate change with you.”’ But he dismisses the idea of currents that can suck a swimmer under: ‘it’s nonsense. I didn’t experience that at all. It was fast, though, down to Chelsea it was super-fast, I was flying. I doubt the PLA will grant permission to anyone to swim the tidal section of the Thames now they have legislated on the issue. Sadly, I was the first, and, it would seem, the last person to swim the full length of the Thames.’

Other long-distance swimmers, however, have more sympathy with the PLA. In 2010 American adventurer Charlie Wittmack also wanted to swim through the capital as part of his world’s longest triathlon. But he had to get out at Lambeth Bridge and run through the capital before re-entering the water downriver of the Thames Barrier. ‘I met with the PLA and had a really interesting conversation,’ he remembers. ‘I had friends attuned to the legal issues and when I went to meet the PLA I knew there was no law that was prohibiting me from swimming through central London and down to the east barrier. So I met with them essentially to get their blessing, and then I learnt just what a dangerous place it was to swim.

‘As an adventurer and extreme athlete I’m always careful that people need to do the proper training and preparation. Most things I do like Everest, others aren’t going to do; it’s not on their doorstep. But the Thames runs through the heart of one of the most populated cities in the world. In the legal world we refer to those type of things as an “attractive nuisance”; people might see me and might want to take on the same challenge. The decision was mine, I got out at Lambeth, the BBC was there and we tried to use the coverage to discourage people from the central London section because it’s too dangerous, so there were media stories that even the most experienced adventurers wouldn’t do it.

‘It’s a complicated issue and I would defer to the experts at the port authority. We discussed that the new regulation was coming and wasn’t yet in effect, and in a sense it created an opportunity for me to be the last person to swim the entire length, and I was excited about that, to do a challenge that would thereafter become impossible. The PLA were frustrated; they knew it was dangerous and they didn’t have the legal authority to prevent it. That’s an unusual situation to be in! The new regulations are probably good; any regulations that protect life and health are good and important. And, after all, there are other challenges to do in the world.’

The next year, when David Walliams set off on his Thames journey the original idea was once again to swim through London, but he agreed to leave the water at Westminster Bridge. ‘The PLA didn’t want us to do it at all,’ he recalls, ‘they said people would emulate me. Every year there are fatalities, people drown. It’s a hard one to deal with. People might do that and they might not, it could even put people off because they saw me on TV.’ David says the new by-law is ‘sensible; to get in the Thames in central London is crazy, it’s dangerous and there’s lots of traffic. I had a team and everyone knew I was doing it but, even then, I was hit by rowers. People are not expecting to see you there. The PLA’s job is to protect people, they are answerable to the government and the Mayor and no one wants fatalities. But we were raising two and a half million pounds and hopefully saving people’s lives. I’d have liked to continue to the Thames Barrier and ultimately to the sea but at the barrier there’s nowhere to stop, the charity was concerned about having a media event, and at the Houses of Parliament you had a crowd and good shots. The PLA said I had to get out and to get back in would have killed the momentum. In Sport Relief challenges there’s always a risk, people have died swimming the Channel, or climbing Kilimanjaro. It was hard to walk away because someone might copy me, and actually I haven’t met anyone who’s said, “that looked nice”. They’re more likely to say, “I can’t imagine how you did that.”’

The 2012 by-law was ‘confirmed’ by the Department for Transport, after ‘extensive consultation’ and advice from the RNLI, the Maritime Coastguard Agency and the police, that ‘attempting to swim in the River is dangerous and should not be undertaken’. The PLA argued that not only had swimming in central London not been allowed for years, but the by-law was in the interests of other river users, ‘as a boat having to stop suddenly or swerve to avoid a swimmer could put the boat and/or its passengers at risk of injury … passenger services are a growing part of the commuter and tourist travel network in London and freight services keep thousands of lorries off London’s roads’. It was at pains to point out that the by-law would not prevent ‘a David Walliams-type charity swim’, but was designed to ‘balance the interests of all river users in the use of our great river. To be clear: we have not “banned” swimming over the 95 miles of river that we cover. From Teddington Lock to Putney and from Crossness to the North Sea there are no explicit requirements, bar people using their common sense.’

‘Swimming in the Thames is akin to rambling on the M25. A hazardous undertaking.’ A 2012 by-law prevents people from swimming between Putney and the Thames Barrier without a licence from the PLA.

But many people reacted furiously to the by-law. On internet forums some said it was a result of Trenton Oldfield’s disruption of the boat race a few months earlier, others that the PLA was ‘another nanny among the thousands blighting the daily life of Britain’. One commentator said if you had to apply for a licence before swimming it ‘removed any spontaneity’ and was therefore a de facto ban; another wondered whether the licence issued was waterproof so that it could be produced when asked for.

The by-law still remains controversial and so, when Martin Garside, corporate affairs manager at the PLA, offers to take me out on a patrol boat to illustrate why it’s not a good idea to swim through central London, I leap at the chance. It’s a cool November afternoon when we meet at a coffee shop near Tower Pier, along with Steve Rushbrook, PLA deputy harbour master for the tidal Thames in the London area. He’s been with the PLA for twenty years, while his father used to work on a Thames salvage boat. Martin has a printout he wants me to see, a list of incidents from January to October this year. So far there have been 153 ‘confirmed persons’ in the river - either dead or rescued - and 34 ‘possible persons’. There have been 23 swimmers in difficulties, 19 people cut off by the tide and 18 people in the mud. There have also been 230 incidents of people threatening to jump into the Thames. Police helicopters have been called out 71 times, the RNLI lifeboats 747 times. In total, 2,330 people have been saved or assisted, and 35 have died.

I’m shocked by the figures, as Martin intends me to be, especially the fact that an average of thirty-five to forty-five people die in the Thames in central London every year, and the latest statistics only go up to October. ‘Christmas is coming; people will have drunk too much,’ says Martin. ‘These figures show the range of all human behaviour, from a man trying to impress his girlfriend, to drunken acts of bravado, to endurance swimmers. People inadvertently fall in while walking a dog, there are attempted suicides. A classic is to try and swim across when drunk. It’s a dangerous place. The Thames is not a theme park or adventure playground.’

A few months ago Martin went to the funeral for a young man who died at Gravesend; ‘one second he was there and then the other second he was gone. He was strong and fit and he had gone to help people in trouble. There are some frustrations with us; people think we’re faceless bureaucrats, but Steve lives and breathes the river, as his father did. We love the river, too, but a body is found once a week. We help recover them, we meet the families, we are in a different place from those who want to swim.’

‘Every day we get the coastguard report,’ adds Steve, ‘overall we’ve seen a steady rise in the figures. Swimmers are a summer phenomenon; you don’t see them in the first part of the year, and then it increases.’ Martin says half a dozen people now contact them every year, saying they want to swim the Thames and are doing it for charity. ‘They are very vague. We ask, “what charity are you doing it for?” They say, “I don’t know.”’

Martin has brought me a book commemorating the PLA’s century of service from 1909 to 2009, its jurisdiction now running ninety-five miles from Teddington to the outer Thames Estuary. It helped rebuild the Port of London after the Second World War, made the river safer and cleaner, and ‘reconciled the diverse ways in which the tidal Thames is used’. Out of habit I turn to the index and look up ‘Swimming’. There is a single reference in the 230-page book: the PLA’s swimming club’s annual open-air gala at the Millwall Cutting at the West India Dock in the early 1930s, watched by 4,000 people. A page on sport on the river doesn’t mention any swimming, but explains the PLA has overseen the annual university boat race since the Authority was created, and is now involved with coordinating fifty major events.

Martin says that while the Teddington to Putney stretch is OK for swimmers, below Putney, where the channel is narrower, there are issues of tide, transport and bridges. ‘If a swimmer meets with a boat, the swimmer will come off worse. They say it’s about their freedom to do this, but what would a skipper with a vessel of two hundred people on board do? Mow them down? But he’s human; he would swerve to avoid them. So does he crash into a bridge, or into another vessel? This is what we asked David Walliams: “what would a boat do?”’ The PLA would have preferred David to leave the water at Vauxhall, which they say would have been a safer option, and when he wanted to swim to the barrier there were ‘tense negotiations’. The PLA presented him with the hazards and there was a debate between ending at Vauxhall and Westminster. As for potentially falling ill from swimming in the Thames, ‘he said he’d be inoculated, but against what? I’m not a doctor but I can’t see how you can be inoculated against an intestinal parasite.’

Random wild swimmers are reckless, says Martin, and while the circumstances are different, the river overwhelms them very quickly. ‘It’s not about us stifling individuality; it’s a busy highway. If someone swam from Putney or Hammersmith, we’d want to be advised. If it’s in central London, then no.’ Swimming across the river, he explains, is more difficult than swimming along it. ‘We have given a licence to swim beyond Putney; people can do Putney to Vauxhall if it’s risk-assessed. A swim involves a lot of management, and some cost. The burden is on them to do the risk assessment, but then the by-law is there to protect them. The “b” word I would use is balance, not ban.’

The Port of London Authority’s control centre overseeing the river at Woolwich. An average of thirty-five to forty-five people die in the river in central London every year.

When I comment that some experienced Thames swimmers dispute the dangers of eddies and underflows, he laughs in disbelief. ‘Those who don’t believe they exist, we would gladly take them out and show them.’ And with that we pay for our coffee and head back to Tower Pier for a boat ride.

Before I get on board the PLA patrol boat I’m given a life jacket, which has a canister inside. ‘It will inflate if you fall in,’ says Martin, ‘if you do, don’t try to swim, just wait to be rescued.’ I step a little gingerly on to the boat and walk to the front where there is a man at the wheel. ‘Bob,’ says Martin introducing us, ‘this is Caitlin. She’s doing a book about swimming the Thames.’ Bob Bradley, PLA marine river inspector, doesn’t look round. He just gives a heavy sigh. ‘Stick to swimming pools,’ he mutters.

We set off upstream towards London Bridge, while Martin gestures repeatedly out of the window: ‘the tide is going out now, so we’re going against it. Look at the current around those buoys.’ He wants me to understand what would happen to a swimmer in these waters: ‘if you come up against a barge or something you go straight under. You could hold on to a tyre, but not for long. You could get hold of a grab chain’, a series of chains looped across the walls and put up after the Marchioness disaster, ‘and hang on the side, but you won’t last long and you will be being dragged through the water.’

The sinking of the Marchioness was one of the worst river disasters in modern times. In the early hours of 20 August 1989, the 90-ton pleasure cruiser was run down by the 2,000-ton dredger Bowbelle, near Cannon Street Railway Bridge. The Marchioness sank in less than a minute and fifty-one of the 131 people on board, most of them attending a birthday party, drowned. The causes were said to be poor visibility, both vessels using the centre of the river and lookouts not being given clear instructions. As a result of the tragedy, safety on the Thames was tightened up, new regulations came into place and in 2002 the first lifeboat service was established, a dedicated Search and Rescue service for the tidal River Thames, with four lifeboat stations, at Gravesend, Tower Pier, Chiswick Pier and Teddington.

‘Look at the waves there,’ says Martin, pointing to the shore on the left. He explains that the Thames carries 70 per cent of British inland waterways traffic and this is ‘category C water’, which means there can be waves at least a metre high. He gestures to a young man standing at the back of our boat; ‘if we threw him in now, with a life jacket on, he would drift down the river’. He then points out more evidence of the tidal flow beneath London Bridge, where water swirls around the pillars; ‘anyone who tells you there aren’t eddies and whirlpools … you would be sucked under,’ he assures me. ‘If we dropped an orange in here and came back for it in five minutes, it would be gone and carried under.’ I look again at the force of the water between the pillars; anyone actually in that spot would be blasted around, and Martin says when someone disappears here, their body isn’t found for four days.

Bob, who has worked for the PLA since the 1960s, has been onsite within five minutes of a report of a person or body in the water and couldn’t find anyone. He was off duty during the Marchioness disaster, but was at the scene within forty minutes and found no one there either. Many survived the impact, he says, but died in the river. The PLA now have rafts that can be inflated quickly to hold up to sixty people. So far the only time they’ve used them was to try and save a whale.

Bob turns the boat around and we head downstream. I ask Steve what this scene would have looked like in Victorian times. ‘They had wharves and lighter boats twenty-four/seven, they had all sorts of boats, but they wouldn’t have had the piers. The Thames is narrower here now, so the tidal stream is faster, and it’s more enclosed. It was more common to be on the river then. But they wouldn’t have had as many passenger boats.’

Bob stops the engine; we’re going with the tide now and we’re moving fast as we reach Wapping police station. ‘I don’t want to be macabre,’ says Martin, ‘but this is where the bodies go.’ He points at a pier with a little shuttered boathouse. ‘If we got a report of a body right now,’ he says as we turn and head back to the Tower, ‘we’d go and find it.’ I think of Andy Nation and Lewis Pugh, both of whom argue that as long as we do it safely we should be allowed to swim in what is a free public resource. But, on the other hand, I wouldn’t want to have Martin’s job and to have to explain to inexperienced swimmers why this stretch of the Thames can be treacherous, or to be the one on call when a swimmer dies.

Steve would prefer no swimming all the way from Putney to the Thames Barrier: ‘it’s dangerous, however strong a swimmer you are.’ Yet what about all the old Thames swimmers, those like Horace Davenport, who won the first long-distance amateur championships in 1877 from Putney to Westminster; Annie Luker, who in 1892 swam from Kew to Greenwich; and Montague Holbein, who managed forty-three miles from Blackwall to Gravesend in 1899? There they were racing in the filthy waterway, surrounded by hundreds of boats and watched by thousands of spectators, and there was no law to stop them. I haven’t even got started on all those who came after them - Annette Kellerman, John Arthur Jarvis, Lily Smith and Eileen Lee - when Martin turns away from surveying the river out of the patrol boat’s window and asks: ‘The Victorian era? Wasn’t human life cheaper then?’