Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames (2015)

13

Putney

‘Swimming [is] the best sport in the world for women’

Annette Kellerman, 1918

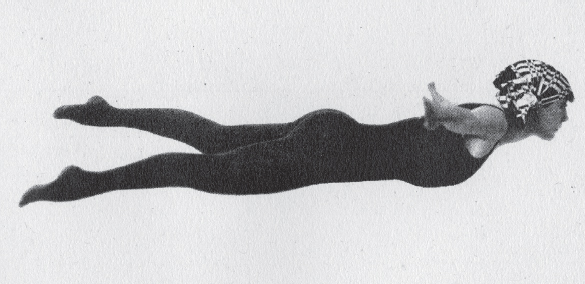

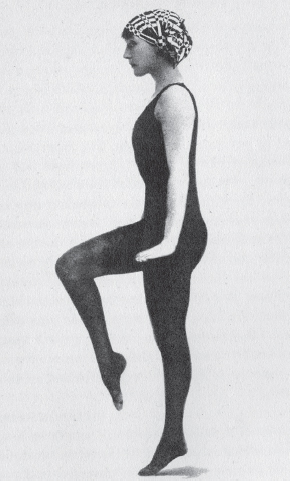

Annette Kellerman is one of the few women champions still internationally known today. Here she demonstrates the breaststroke.

Putney Bridge in west London is a significant spot in the history of Thames swimming for several reasons. It was here, for example, that in 1905 Australian Annette Kellerman began a swim that would launch her international career, while today people are no longer allowed to swim downstream from Putney to the Thames Barrier without a licence from the PLA. I approach from the Putney side of the bridge, down the high street from the station, where I can see the fifteenth-century tower of St Mary’s church just on the riverside. At the other end of the bridge is All Saints’ church, and according to local lore the two sisters who ‘founded’ the churches lived on opposite sides of the river. When they visited each other they gave instructions, either ‘Full home, waterman’ or ‘Put nigh’, and thus the two towns earned their names - Fulham and Putney.

But this is no quaint river crossing and, as with Kew Bridge, travelling across the Thames here is more like walking beside a motorway. Traffic thunders along the A219, and there are so many buses, vans and cars that it’s a relief to pause for a moment and rest my eyes on the water below. The Thames is wide, with patches of shore along the banks, but it also feels like a river in a city; I’ve long left the countryside behind.

At the Fulham end of the bridge I walk down steps to Bishop’s Park. The noise of the traffic is suddenly silenced and all I can hear are birds. The recently renovated park has its roots in Victorian times and its facilities now include an ‘urban beach’ for children to play on, although not on the river itself. I stop in the sculpture garden in front of a statue of two figures in stone. They seem to be embracing; perhaps it’s a love story. Then I bend down to read the plaque beneath it where I can just make out a single word: GRIEF. Suddenly the sky thickens with clouds and when I look behind me the water beneath Putney Bridge has been thrown into threatening dark shadow. I think of Mary Wollstonecraft, the feminist philosopher and writer best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, who in 1795 threw herself into the river here. In April of that year she had returned to England from a trip to Scandinavia to learn that her lover and the father of her child, Captain Gilbert Imlay, had moved in with another woman. One November night in heavy rain she jumped from Putney Bridge - some reports say she rented a boat and rowed over to Putney after finding Battersea Bridge too crowded. Incredibly, she was pulled out of the water alive and taken to a doctor. Wollstonecraft had left Imlay a letter, written ‘on my knees’, imploring him to send their daughter to Paris. ‘When you receive this, my burning head will be cold … I shall plunge into the Thames where there is the least chance of my being snatched from the death I seek.’ Wollstonecraft survived, returned to her writing career and two years later married William Godwin, dying as a result of childbirth in 1797. How desperate she must have been, and how ideal the Thames would have seemed as a place to end it all for someone who couldn’t swim.

But as is often the case in the story of the river, this was also the setting of joyful occasions and in the nineteenth century Putney was the starting point for several races between champion men. In August 1869 the first ever amateur mile race in the Thames, from Putney to Hammersmith, was won by Tom Morris in twenty-seven minutes eighteen seconds. The long-distance amateur championship also began (or ended) at Putney, before the course was changed to Kew. In July 1877 the inaugural winner was Horace Davenport from the Ilex Club who swam from Putney to Westminster in just over one hour thirteen minutes. Davenport was ‘the finest long distance amateur swimmer that England has ever seen’, according to The Badminton Library of 1893; he played an important role in the ASA and one of his later feats was swimming from Southsea in Portsmouth to Ryde in the Isle of Wight, and back.

Other races for men were held at Putney in Victorian times. In 1874 there was a two-mile swimming championship to Hammersmith, won by E.T. Jones from Leeds, ‘champion swimmer of the world’, who had recently won the mile championship in the Serpentine. Two years later Jones again raced the same Thames course and won, this time against another famed swimmer, J.B. Johnson, for a cup ‘instituted by the Serpentine Club, which represents the championship of England’ with a ‘hundred pound aside bet’. The press reported thousands assembled on the towpath and bridge, and the ‘scene on the river was quite unprecedented’. In 1895 Professor G. Peat, ‘well-known high diver’, decided to dive from Putney Bridge and swim to Hammersmith, where he also dived off the bridge, ‘for a wager and a medal’.

But for me it is Annette Kellerman’s swim from Putney that is most memorable, for she is one of the few women champions from the past still internationally known and honoured today. Born in 1886 in Sydney, New South Wales, her father was Australian and her mother ‘one of Paris’s greatest pianists’. As a child she had ‘a very distressing’ leg condition, probably rickets, and wore leg braces until she was seven. Once the braces were off, and following medical advice, she started swimming. By the age of sixteen she was the 100 metres world record holder. She then set a women’s world record for the mile in thirty-two minutes twenty-nine seconds, a time she later lowered to twenty-eight minutes, and her first long-distance swim was ten miles in Melbourne’s Yarra River. She also gave exhibitions of swimming and diving at the Melbourne baths, and swam with fish in a glass tank at the Exhibition Aquarium. Then, with her father, Frederick, she set sail for England to try and ‘swim back the family fortune’, lost in the Depression of the 1890s.

During the long voyage from Australia she paced the decks to keep fit, often walking as much as ten miles. But London, she later wrote, was the ‘bitterest disappointment’ of her life and the streets ‘as still as the dead’. Father and daughter rented rooms in Gower Street and approached local swimming clubs, but according to her biographer Emily Gibson ‘there was no chance of Annette performing as a professional in a country where an amateur was seen as superior’. However, the British press had already reported that Kellerman was here to swim the Channel and ‘she will probably do some record breaking while in England’. Soon she was giving an exhibition of fast swimming at an indoor bath, the press explaining she ‘hails from the land of the Cornstalk’ (‘cornstalks’ was a term sometimes used to describe ‘the first generation of non-indigenous inhabitants’ born in Australia), with a debut that included the ‘standing-sitting-standing honeypot’ or ‘cannonball’ dive. Kellerman demonstrated the then popular trudgeon style (similar to front crawl) at Westminster Baths, as well as swimming ‘a length on her side with her hands tied behind her back’ and some fancy diving, ‘giving the Australian “Cooee” just before disappearing’.

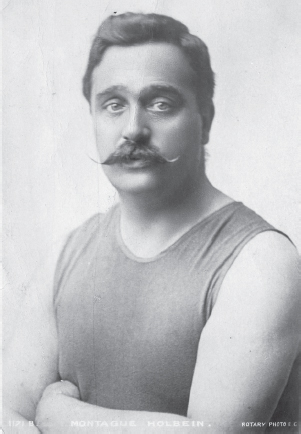

‘Try swimming, old chap.’ Montague Holbein, who in 1899 covered forty-three miles from Blackwall to Gravesend and back, the longest Thames swim ever recorded at the time.

But with their money running out, father and daughter moved to King’s Cross, where Kellerman stayed in a windowless attic room. Then Frederick came up with the idea for a publicity stunt: his daughter would swim the Thames. After all, what better place could there be for Annette to make a name for herself than England’s most famous river? The Auckland Star reported that she had taken up residence near Kew and ‘is in active training for her proposed attempt to break the records of Montague Holbein, Fred Bownes and Matthew Webb in the matter of long distance swims in the Thames’. No mention is made of any women’s records Kellerman may have wanted to beat, as if those who came before her never existed; or perhaps it was just seen as more dramatic and newsworthy for a woman to attempt to break a record set by a man.

On 25 July 1899, Montague Holbein had swum from Blackwall two miles past Gravesend and back, covering forty-three miles in the longest Thames swim ever recorded at the time. He began at Blackwall Pier, ‘went down river on a strong ebb’ and then turned with the tide after Gravesend and ‘came back on the flood to Blackwall’. Although he didn’t manage to reach the pier ‘owing to the tide failing him’, he left the water ‘quite fit and strong’ after swimming for just over twelve hours. He used a slow but powerful stroke, described as ‘half-side, half-back’.

Born around 1862 in the Thames-side town of Twickenham, Holbein was a cotton ‘warehouseman’ and had already achieved ‘practically world-wide fame’ for ‘some marvellous feats on a bicycle’. He was also a cross-country runner and distance walker. A man of ‘exceptional physique and power’ according to the press, ‘he made one of the finest distance riders English cycling ever produced’. He broke a number of records and in 1891 came second place in the first Bordeaux-Paris bike race.

But a cycling accident, which fractured his leg and left him lame, forced him to retire and, as with Annette Kellerman, doctors advised him to turn his attention to swimming. ‘When I recovered, my leg was very stiff,’ he later wrote. ‘My doctor said to me: “try swimming, old chap; it may benefit the limb.” I took his advice, and to my great surprise became so fond of the water that the idea struck me to break records in it as well as on land. I have never gone in for quick swimming, staying being more to my liking.’

Holbein definitely had staying power. In 1908 he would manage an incredible fifty miles in the Thames, without leaving the water. Again he began and ended at Blackwall, finishing the swim in just over thirteen hours, and ‘anybody seeing him climb the ladder lowered from the tug in attendance would never have dreamed that he was returning from a fifty mile swim in rough water’.

Holbein also became noted for his attempts to swim the Channel. In 1901 he was pulled out four miles from Dover, his eyes so damaged by the salt water that he couldn’t see for four days. The following year he wore a mask made of ‘sticker’s plaster’ with glass, but this attempt failed - ‘I was completely blind, and in considerable agony’ - as did the next. In 1914 he wrote a book entitled Swimming, whose opening words were: ‘Everyone ought to know how to swim. We are a nation of sailors … and yet swimming is an art, even to-day, which is strangely neglected.’ Unusually for a champion who made his name in the Victorian age, Holbein was still swimming in his later years. In August 1936, at the age of seventy-four, he covered eighteen miles from Richmond Lock to London Bridge. Images from the time show him preparing for the swim, being greased down ready to start his journey, his white handlebar moustache as bright as his swimming cap. He died in 1944.

Fred Bownes, meanwhile, the Australian press explained, had swum just over twenty miles from Blackwall to Gravesend (no date is given), while Webb had managed forty miles in the Thames in 1878. It was the records of these two men, as well as of Holbein, that Annette Kellerman apparently intended to beat, although exactly how isn’t clear considering her route was far shorter than either Holbein or Webb’s.

‘I shall never forget that swim through the flotsam and jetsam of London’: Annette Kellerman demonstrates how to tread water.

On 30 June 1905 her father hired a boat and a boatman and, on a diet of mainly bread and milk, she dived into the Thames at Putney. ‘It was an awful trip,’ she later wrote. ‘I shall never forget that swim through the flotsam and jetsam of London, dodging tugs and swallowing what seemed like pints of oil from the greasy surface of the river.’ As she got to Blackwall ‘three and a half hours later’, the press had arrived in time to see her getting out, covered in grease. ‘I was absolutely starving, and there was nothing to eat. Lunch had been forgotten. The wharf-keeper’s “tea” of bread and cheese had just been brought, and he generously gave it to me. Never before had food tasted like these hunks of bread and cheese which I devoured, sitting on the wharf in my bathing costume.’

While Kellerman is one of the few women from the early 1900s whose name hasn’t been erased from sporting history, details of her swims - their lengths and exact dates - are contradictory. According to the Annette Kellerman Aquatic Centre and her biographer, she swam twenty-six miles in five hours; the Sport Australia Hall of Fame puts it at sixteen miles. But British and Australian newspapers of the time reported it was thirteen and a quarter miles, which she completed in three hours, fifty-four minutes and sixteen seconds. If it was thirteen miles (and Kellerman’s own reference to the swim lasting under four hours suggests it was) then it was by no means a record for a woman in the Thames. Annie Luker, for example, had swum fifteen miles in 1892. But even then the Brisbane Courier found it hard to accept. ‘The record for the mile is 23min 16 4/5 sec, standing to the credit of B.B. Kieran, and the figures as cabled give Miss Kellerman an average much under record time. If the figures are correct, it is obvious that Miss Kellerman must have had the assistance of tide.’

In the UK, the Daily Mirror saw an ideal opportunity for publicity and decided to sponsor her Channel swim, inaccurately said never to have been attempted before by a woman. The only person to have successfully made it across unaided was Captain Matthew Webb and that had been thirty years earlier. The paper paid her expenses and a fee, and in return had exclusive coverage. It offered her eight guineas a week to swim along the coast in preparation and for the next two months she swam from Dover to Margate, averaging forty-five miles a week. She was also sponsored by Cadbury’s Bournville Cocoa, which she drank regularly during her trial swims although it made her sick.

In July 1905 she ‘beat all records for the swim from Dover to Ramsgate’, covering around eighteen miles in four hours twenty minutes, beating a time set by Jabez Wolffe byten minutes. The course had only ever been completed by three men, including Captain Webb. The Dover Express devoted some space to her successes so far, describing her as 5 foot 7 and weighing 12 stone. Another paper insisted that her training performances were ‘accompanied by weird Maori yells, which greatly heightened the excitement’. A few years later a group of ‘Maori Girls’ would swim fifteen miles in the Thames from Richmond, telling the press ‘we are almost an amphibious race’ and dismissing the distance as ‘child’s play’.

In August 1905 a group of seven swimmers began their Channel attempt - among them Kellerman, Holbein, Wolffe and Thomas Burgess (who in 1911 would become the second person to succeed after Webb) - starting from different spots. Kellerman set off from Dover, covered all over with porpoise oil and with her goggles ‘glued on’. The men were allowed to swim naked, ‘but I was compelled to put on a tiny bathing suit’ which left her armpits chafed raw. Did she really intend to swim the Channel naked? It seems an incredible thing to do, considering the amount of publicity surrounding the event and the fact that Edwardian ‘ladies’ were still expected to be covered from top to toe at all times, even on the beach.

Thomas Burgess was one of seven swimmers, including Annette Kellerman, who in August 1905 attempted to swim the Channel. In 1911 he became the second person to succeed after Captain Matthew Webb.

Kellerman lasted six hours, and although she had to give up on this attempt because of rough seas and seasickness, as well as two further attempts, it stood as a women’s record for many years. ‘I had the endurance but not the brute strength,’ she wrote in 1919. ‘I think no woman has this combination; that’s why I say that none of my sex will ever accomplish that particular stunt.’ But then, of course, in 1926 Gertrude Ederle became the first sportswoman to cross the Channel. She wore silk trunks and ‘a narrow brassiere’ (which she removed once she got going), making her possibly the first sportswoman to swim in what would eventually become the bikini. Kellerman later said she favoured women over men when it came to long distances ‘because we have more patience’, and challenged any man in the world to swim against her at any distance over ten miles.

One British paper praised Kellerman’s ‘powers of physical endurance of mean order, and for a mere girl in the first bloom of womanhood to battle with the waves for six hours is little short of marvellous’. She quickly became a celebrity, and was invited to swim for the Prince of Wales (later George V). But she wasn’t allowed to appear with bare limbs, so she sewed a long pair of stockings on to her suit, thus inventing a prototype of her one-piece costume that would revolutionise the world of swimming for women. Despite her failed Channel attempt, Kellerman then set off for France where in September the same year she competed against seventeen men racing down the Seine, finishing joint third with Burgess, and watched by half a million spectators. She also beat the Austrian swimmer ‘Baroness Isa Cescu’ in a twenty-two-mile Danube River Race from Tulln to Vienna. This was presumably Madame Walburga von Isacescu, whose record Eileen Lee would break in 1916.

Kellerman was as well known for her swims as for what she wore. Aside from wanting to swim the Channel naked, and being made to cover up before appearing in front of the Prince of Wales, in 1907, while about to do a three-mile swim, she was arrested on a Boston beach for wearing her one-piece costume - at a time when most women were still wearing corsets, sleeves and a hat. She was charged with public indecency in what may well have been a cleverly orchestrated publicity stunt. During her court appearance she said it was more criminal for women to have to wear so many clothes in the water; they would never learn to swim and they had a greater chance of drowning. The judge allowed her to wear her suit, if she kept it hidden under a robe until the moment she got into the water. She went on to design the famed ‘Annette Kellerman black one-piece suit’, the first modern swimming costume for women.

Kellerman’s legacy is incredibly important: she was a record holder, made impassioned arguments about clothing that restricted women’s movement, and her career illustrates how ‘the fairer sex’ could find physical freedom as well as international recognition through sport. The Thames was central to this story; it was where women displayed their stamina and endurance, both physical and mental. Kellerman wasn’t an outspoken champion of women’s rights in the same way as her successor, Lily Smith. ‘I am not in favour of women’s trying to ape men in athletic affairs. I am glad this sort of new woman is dying out,’ she wrote in 1918, but she did devote an entire chapter of her autobiography to an examination of the position of women in a male arena.

Swimming, she believed, was ‘a woman’s sport’ because men had so many other sports ‘where women make a poor showing’ or weren’t allowed to compete. ‘I am not trying to shut men out of swimming,’ she wrote. ‘There is enough water in the world for all of us.’ But women were more graceful than men, had almost as much strength, and could nearly equal them in terms of distance. Men swimmers, she noted, had ‘physiques more nearly resembling those of women’ and she found Jabez Wolffe ‘pretty fat for athletic work’. Swimming she concluded ‘will make the thin women fat and the fat women thin’.

Swimming was also the only sport in which women were ‘catching up’ with men; in long-distance swimming women’s world records came within 10 per cent of equalling men, while in running it was 73 per cent and in ‘strength’ events it was 60 per cent. In addition, women had more ‘fatty tissue’ which meant they stayed warmer, could more easily float and were less liable to get cramp.

But the topic Kellerman was most passionate about was clothing and her book includes numerous images of her wearing ‘suitable tights’ for exhibiting diving, an ‘ideal bathing suit’ for public beaches ‘where swimming tights are not permitted’, a jersey swimming cap for going to and from the water, and a fashionable silk bandanna worn over a rubber bathing cap. Women, she explained, needed to exercise their knees, which walking in skirts prevented, and attempting to drag loose-flowing cloth garments through water was ‘like having the Biblical mill-stone around one’s neck’. There was no more reason that a woman should wear heavy, awkward bathing suits than there ‘is that you should wear lead chains’.

After retiring from long-distance swimming, Kellerman toured theatres across Europe and the United States starring in aquatic acts as the Australian Mermaid and Diving Venus. She is said to have pioneered water ballet, today’s synchronised swimming, although she once wrote that ‘this trained seal stuff gets on one’s nerves’. In 1908 a Harvard academic, who had apparently examined the physiques of 10,000 women, declared she ‘embodies all the physical attributes that most of us demand in The Perfect Woman’. Kellerman told reporters, ‘I’m perfectly healthy, that’s all.’

She revisited England a number of times, giving free lectures for women in 1913 and appearing in shows in the late 1920s where she was billed as the ‘leading exponent of physical education and wonder woman of the water’. In 1912 the Cheltenham Looker-on, in a feature called ‘women’s chit-chat’, described her as ‘an authority of physical culture’ who ‘holds that swimming is the best of all exercise for girls’. Attitudes to women swimming were certainly changing; there were more swimming baths, some allowing mixed bathing, seaside resorts had dropped the Victorian regulations and ‘finally, the old, ugly cumbersome bathing dresses have been discarded’ and ‘any woman can now wear without inviting remark the tight fitting stockingette style dress, most convenient for swimming’.

Kellerman went on to become a Hollywood film star, one of the main reasons she’s still remembered today, with all the accompanying glamour, publicity shots and international audience. She starred in Neptune’s Daughter in 1914, where she set a ‘world high diving record’ of 28 metres, and performed her own stunts, including leaping into a pool of crocodiles. In A Daughter of the Gods she appeared in many scenes naked and although she later insisted she was wearing ‘very thin tights’, this was made much of in the film’s pre-publicity.

Kellerman’s athletic achievements, like those of Annie Luker, Lily Smith, Ivy Hawke and Eileen Lee, led to a shift in public attitudes towards women. If we could swim as fast and as long as men, and perform equally perilous dives, if we could easily rise to the challenge of the Thames or the Channel, then maybe we weren’t the ‘weaker sex’ after all. Perhaps we could even cope with having the vote. ‘Those who contend that woman is too weak physically to contend with a man at the voting booth and therefore should be denied the franchise should go to see Annette Kellerman in A Daughter of the Gods,’ declared the New York Times Journal. ‘If votes were obtained by physical or mental courage,’ echoed the Boston Post, ‘Miss Kellerman would demand a million of them.’

In 1918 she wrote a bestselling book, Physical Beauty and How to Keep It, and travelled the United States lecturing on health and fitness. In 1952 her life story was turned into a film, Million Dollar Mermaid, starring swimmer-turned-actress Esther Williams. In 1974 Kellerman was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame, the same year of her death at the age of eighty-nine.

Kellerman’s 1905 swim in the Thames from Putney wasn’t an isolated event in terms of women’s swimming, although it’s usually treated that way today. Although she doesn’t appear to have made any mention of those who came before her, and she must have known about them, she was building on a tradition that went back to Victorian times. Today the memorabilia that survives from her career is extensive - film posters, colour postcards, press shots, adverts for Black Jack liquorice, cigarette cards, along with her own books, a biography and a picture book for children. Yet when she is written about now it is as if what she did in the Thames and elsewhere was unique and had never been done before or afterwards. Kellerman, we are led to believe, was the exception.

Eighteen-year-old Agnes Nicks surveys the Thames opposite the Houses of Parliament in 1928. She became known as a cold water expert.

She wasn’t the only woman to choose Putney as a place to begin a swim. In March 1931 it was the turn of a cold-water expert, twenty-one-year-old Agnes Nicks, who attempted to swim the university boat race course from Putney to Mortlake in water that was 35 degrees and to ‘break the standing cold water record’ held by Dorothy Wiggin of California. But she was taken out ‘in a state of exhaustion’, put aboard a boat and ‘conveyed to a riverside house, and there put to bed, and surrounded by hot water bottles’. A few months later Nicks was back. In October she became the ‘amateur long distance record holder’ by completing a ten-mile swim from Putney to Tower Bridge in two hours to ‘inaugurate her “cold water season”’. She then dashed off in a taxi to Holborn Baths ‘to wash away the oil and petrol of the Thames’.

In November Pathé News filmed ‘Miss Nicks swimming in the Thames near the Houses of Parliament’. The caption reads: ‘October, November or December weather means nothing to Miss Nicks - she begins just when most other Eves leave off.’ Nicks does a rapid front crawl, alongside a male swimmer described as her trainer, and accompanied by a small boat. She appears to be arriving at Westminster Bridge and then at Tower Bridge where her trainer helps her staggering out of the water and looking near to collapse. Did Nicks know of Kellerman’s swim in the Thames twenty-six years earlier? She would certainly have been familiar with her through her films, and the press covered Nicks’ swim much as they had done her predecessor’s. ‘And still they speak about the weaker sex!’ reads a second Pathé caption, driving home the fact that women might now have the vote but that didn’t mean we were men’s equals. The clip ends with Nicks sitting on a pebbled shore, rubbing her hands and then clutching a towel to her face. Repeatedly described as ‘a London typist’, she appears to have been a member of the Excelsior Club of Highgate, which means she would have swum at the Kenwood Ladies’ Pond on Hampstead Heath, a favourite venue for year-round swimmers - as it still is today.

In the 1930s, meanwhile, swimmers had a new facility at Putney where a ‘beach’ was established at Putney Embankment, which continued into the 1940s. Photos show a sloping stone embankment busy with sunbathers, bikes, prams and dogs, while children paddle in the Thames. Perhaps like schoolchildren at Chiswick forty years later they were attracted to the river because there was no longer an indoor swimming pool at Putney; the baths which had opened in 1886 had closed, and there would be no indoor provision for swimmers until 1968.

Today, on the Putney Pier side of the Thames, is the stone that marks the place where the university boat race starts; it first began in 1829 from Henley, but there’s nothing to commemorate any of the swimming races held here. While the Wandsworth Heritage Service has archives about local swimming baths there is ‘very little if anything about swimming in the Thames,’ explains Heritage Officer Ruth MacLeod. Why is there nothing to commemorate Horace Davenport’s swim in 1877, Annette Kellerman’s in 1905 and Agnes Nicks’ in the 1930s? Where are the monuments, statues and plaques to our swimmers? Sometimes during this journey down the Thames it seems that all we have left are ‘No Swimming’ signs.

But in 2011 there was good news for Putney bathers when local newspapers declared commuter ‘swim lanes’ were ‘to be created in the River Thames for fit commuters following the success of the capital’s “Boris bikes”’. Dredging would begin soon, to ensure the lanes were open in time for the summer. Each lane would be roped off to prevent pleasure boats and debris floating in front of swimmers, while sprinkler systems would operate during peak hours to keep the water clean. The first lane to open would run from Putney Bridge to Westminster, and swimmers would be charged a non-refundable deposit of £1.50 for towel hire. The only problem was, the article appeared on April Fool’s Day.

In reality, as from July 2012 it is now illegal to swim downstream from Putney without a licence from the PLA. So it’s unlikely anyone will ever be able to officially replicate Annette Kellerman’s debut British river swim, as she made her way through the flotsam and jetsam of London swallowing pints of oil and emerging three and a half hours later to sit on the wharf at Blackwall to ravenously eat her lunch.