It Runs in the Family: On Being Raised by Radicals and Growing into Rebellious Motherhood (2015)

WHO YOU CALLING MAMA?

When Seamus was born, I took a leave of absence from writing my regular column for Waging Nonviolence. What was I doing? Getting to know my kid. I struggled with many questions during this time. Who am I when I am not an activist, an organizer, an energetic and creative homemaker, and all of the other roles I have carved out for myself? Who am I, when all it seems I am doing is taking care of this infant?

Eventually, I learned to approach this time with Seamus—and with my family—as a gift, a foundation upon which I could build and grow comfortable with a big new facet of my identity—being a mother.

When Seamus was a happily napping infant, I might get an hour and twenty minutes of grown-up time here and there. The challenge was to use it wisely. I watched a lot of TV on Netflix. While he nursed, I consumed all of Better Off Ted and most of IT Crowd and caught up with those zany kids on That ’70s Show. I figured out what all the fuss was about with Mad Men and watched all six seasons of Lost. Occasionally, it would occur to me that I should be watching A Force More Powerful or a Ken Burns documentary—something edifying—but I was equally happy queuing up another sitcom.

When I was not nursing (which, depending on the day, might be for hours-long stretches or mere twenty-minute snippets), I washed his poopy diapers, frantically ate everything in sight (mostly cold), and tried to stay on top of a few select responsibilities.

My “to do” list used to be a page and a half long: War Resisters League conference calls, Witness Against Torture meetings, my responsibilities at the local food co-op, tending my community garden plot, volunteering at church, writing assignments, speaking gigs, and family responsibilities. I am a list maker, a planner, a do-er. And for weeks, maybe months, I made no lists, I set no plans, and I did very little. Yet, I was active and so was Seamus. We came to know one another, to understand one another, to settle into a relationship as mother and son. I had to learn to be okay with measuring my accomplishments in ounces and pounds gained on a happy baby instead of measuring my accomplishments as items checked off on a to-do list.

It meant learning to fully embrace, enjoy, and celebrate my new role as mother, and to integrate the new responsibilities, graces, and challenges into the person I already am.

Many women have to go back to work after six weeks, and most daycare centers take kids that young. But my husband and I made a choice to live on one salary. This choice means that we don’t go out to eat or to the movies that much, we don’t buy new clothes or expensive computer devices. We don’t have a lot of extra money, but we do have more time for family, for each other, and for the world.

![]()

One Good Friday, I trudged down the side of the road carrying a small sign: “I am waiting for YOU to shut down Guantánamo.” We were marching towards the submarine base in Groton, CT. I was grateful for the orange jumpsuit that added a layer of warmth and the black hood that blurred my sight. It was nice to not be seen. Usually at demonstrations, I like to be out and about. In New York City, where I was an activist with the War Resisters League and Witness Against Torture for twelve years, I often opted to pass out leaflets or hold a lead sign in a demonstration. I even honed an outgoing, chatty, aw-shucks persona that helped me greet everyone with enthusiasm and openness.

But New York City is not Southeastern Connecticut. Even when the response was hostile and barbed in New York, it was brief. Even the biggest haters are in a big rush in the Big Apple. In a city of eight million people, the person who tells you to “Get a job!” or “Move to Russia!” or who wants to “Behead all the Muslims!” is probably not going to be pulling you over for speeding on Route 32 or taking your gas money at the local Pump ‘N Munch.

What I was really worried about was the people I already knew and liked who worked at the base or at General Electric—the big military contractor in the area. I was not quite ready to “come out” as a peace activist.

Until moving to New London in 2010, I had never been friends or even acquaintances with people in the military or people who worked as military contractors. For years I have casually and professionally referred to them as Merchants of Death. I am a second-generation activist whose last name is synonymous with prophetic witness, long prison sentences, and military-related property destruction. We weren’t hanging out with army brats outside the local VFW. My dad was a veteran of a foreign war, but a repentant one. I knew lots of those—men haunted by their time in war, who were strengthened and healed by their resistance. But I didn’t know people who saw the military as a smart career move or a chance for adventure or the only way out of poverty. I wasn’t likely to meet them as a pudgy eleven-year-old wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the message “Join the Army: travel to exotic, distant lands; meet exciting, unusual people—and kill them.”

Now I live in a town that sees its economic vitality as dependent on General Electric, the Coast Guard Academy, and the submarine base. My massage therapist is a subcontractor at Electric Boat, the company that makes submarines. My best friend’s new next-door neighbor makes great beer and also works for EB. Our old downstairs neighbors were in the Navy. When my car battery died, he helped me get my car started again despite my assertion that I knew what I was doing (which I did not). Half the moms in the local La Leche League and the play groups we love live on the sub base.

Joanne Sheehan, my mother-in-law, the nonviolence training guru and long-time War Resisters League staff person, often says that it is easier to “speak truth to power” than to “speak truth to family and community.” She has lived in this area for more than thirty years. I am starting to understand what she means.

It is a new thing for me to relate to people in the military across dinner tables, church pews, and street corners instead of across picket lines. It is harder, in some sense. It is easy to judge and condemn and decry. It is hard to relate and communicate and respectfully agree to disagree.

My husband grew up here. Many of his friends at school were dependent on the military industrial complex. They moved around a lot. They would be in his class for a year while their dad was deployed to the Navy base and then they would be gone. From an early age, Patrick developed the ability to relate to people from different backgrounds and different political perspectives, finding common ground.

He said: “Even though most of the other kids at school had some direct relationship with the military through their parents’ enlistment or employment, and I was the peace activists’ kid, I never had any conflict with those kids. I never hid who I was or what I thought and believed. I worked really hard to find ways of communicating respectfully and nonjudgmentally. I learned to focus on systems, not personalities. I would tell the other kids: ‘I am not against your dad the soldier; I am against the system that bombs cities and kills kids. I think your dad joined the military for the same reasons I am against war.’ I think that I helped kids think more about the world and their role in it.”

After twelve years of being “Peace Pat” in the Submarine Capital of the World, he anticipated going to Earlham—a Quaker college in Indiana where he would major in Peace and Global Studies—as a kind of long-awaited homecoming. “I thought I would find my people! But I found myself less comfortable than I was in high school. It was kind of like: Everyone is progressive, everyone agrees that war is bad, so what do we talk about now? What do we do? How do we use this critical mass of like-minded people to create change? It made me realize that being a peace minority made me sharp and deliberate about who I was and what I thought and how I communicated with other people. It motivated me. At a place like Earlham I could be sort of lazy about it, which made me glad that I had not always been able to do that.”

Patrick is a good sounding board and a great inspiration. How do I get the conversation started with my new peers?

“Hey, I notice you are a really great father. Why do you work on submarines that could annihilate fathers and daughters?”

“How do you sleep at night?”

“Don’t you see the contradictions between your life and your work?”

Or my favorite when I was a kid protesting at the Pentagon: “You can’t run from a nuclear war.”

Patrick and most other small-town activists would tell me that these conversation “starters” actually kill dialogue. They tell me that empathy, compassion, and mutual aid are more effective. So I am letting go of judgment and conversion and starting with real conversation.

![]()

Of course Patrick makes mistakes too. Like the time he left a dirty diaper sitting on the back of the sofa. It was neatly wrapped. I walked by it two or three times before it registered in my tired mind: “Patrick! Gross!” My husband had changed the baby’s diaper and then left it right there.

But then I started to piece together our night. The baby was up at midnight to nurse, then up again at 2, and again at 4, and then again at 5:30—at which point Patrick took the voracious little eater away and I got to sleep deeply until 7:30. Bliss.

Patrick, on the other hand, walked around with a gassy, restless, grumpy baby for the better part of two hours. When Seamus would drift off, nuzzled on his dad’s shoulder, Patrick would try to get comfy on the couch. But then Seamus would wake up again, and there would more walking as the cycle repeated three, four, five times. I picked up the diaper and brought it upstairs to the pail with all the rest of them. I did not give him a hard time about it. Dads get a bad rap these days. They are accused of not doing housework. When they take care of the kids, it’s called babysitting by the Census Bureau. And their earning potential is down. Also, they get Father’s Day, which is kind of a second-rate holiday promoted mostly by the Father’s Day Council, an association of menswear retailers who declared in the 1980s that Father’s Day “has become a ‘Second Christmas’ for all the men’s gift-oriented industries.” Of course, Mother’s Day is similarly commercial. But the holiday will always have that illustrious peace origin story, with Julia Ward Howe’s Peace Proclamation, where she calls for a “general congress of women” to peacefully settle international disputes.

Growing up, we always asked our dad what he wanted for Father’s Day. We’d get a raised eyebrow and a look that read something like: “What I want more than anything for Father’s Day are children who know better than to ask me what I want for Father’s Day.” What do you buy a man so ascetic that he reuses dental floss? One year, we got Phil Berrigan—priest, peace activist, hardcore nonviolent resister—a tie.

Patrick is not quite as ascetic as my dad, but he definitely doesn’t want a new tie. Patrick is that one person who can take the baby when he is red in the face with tears streaming down his cheeks, catching his breath for a new round of screaming. Patrick walks out of the house and down the block, returning ten, twenty, even forty minutes later with a sleeping angel on his shoulder.

He was once a social worker who helped dads resolve disputes with their children’s mothers; he aided these dads in developing life skills, becoming responsible parents, and navigating the court and social services bureaucracies. Now he is a home visitor, working with expectant and new dads, teaching them how to nurture. He teaches “Dr. Dad” and “Daddy Bootcamp” classes at a local hospital for expectant fathers; he coaches them on basics like how to hold a newborn, how to change a diaper, how to soothe a crying child, how to take a baby’s temperature, and how to support mom through the early weeks. Patrick loves these classes. He helps turn apprehension and jitters into excitement and confidence.

He brings all this knowledge, excitement, and confidence home too. He is lightning-fast at changing Seamus’s diaper, even though the little bruiser thrashes and screams and grabs at your hands the whole time. Sometimes it takes me fifteen minutes to change the boy’s diaper. But with Patrick, Seamus starts out belligerent and then he gets distracted by his dad’s elastic face and amazing noises. Pretty soon they are both giggling and Seamus is clean and dry. Patrick plays and soothes and cooks and instructs and tidies and sweeps and tickles.

At eighteen years old, Patrick refused to register for Selective Service, foregoing federal grants and loans for college. Luckily, Earlham, a Quaker College in Indiana, offered special grant and loan programs to conscientious non-registrants, so he was able to get a bachelor’s degree and travel to Northern Ireland to work in conflict resolution. I think it was there, on the old sod, that Patrick developed his gift for gab. The man can literally talk to anyone about anything without compromising his values or letting anyone slide. I have seen him call people out—even his closest friends—for being racist, sexist, homophobic, or just jerks. And he somehow manages to do it without malice or contempt. The people around him respond by becoming more compassionate, considerate, and open-minded.

Whether it is describing radio waves or the life cycle of the cicada, recounting the story of where honey comes from or how clouds are formed, or explaining why some dogs aren’t nice or how princesses benefit from slavery and exploitation, Patrick is constantly in dialogue with our kids about how the world works, how it should work, and how it will soon work better when they apply their energy, enthusiasm, and good ideas to it.

Patrick is a great father and a great partner. Together, we are always learning from one another, always giving the other the benefit of the doubt, always asking questions, always listening, always encouraging and allowing for growth. We are constantly changing as a couple, and our kids are constantly growing.

Before I was a mom, I was a stepmom. Not a role I ever imagined for myself, but one I have embraced with zeal, taking (pacifist) aim at every wicked stepmother story on the library shelf. I met Rosena at a War Resisters League meeting when she was just two months old. Patrick had come to show off his dark-haired, blue-eyed wonder child. She cozied up in my arms and promptly fell asleep. When Patrick took her away, joking that I was bogarting his baby, I laughed as I handed her over. But I felt a strange sense of loss that I did not understand until all of a sudden I was living with her in an apartment in New London four years later.

She accepted me right away, making room for me in her already busy, bustling family. Rosena’s “big loving family” includes her mom, Patrick’s parents “Nana and Papa,” and Patrick’s sister and brother-in-law, Annie and Chris. And now my mom and the rest of my family swells its ranks even further. At school, to her friends and teachers, she refers to me as “My Frida.” I was not really surprised to be so lovingly embraced by this four-year-old child when Patrick and I fell in love. In a way, it seemed like cosmic payback for embracing all sorts of random grown-ups and their roles in my life when I was a kid. But I was surprised by how comfortable I was with the family arrangement of three days with Rosena, four without, then four days with and three days without. I always looked forward to her coming to our house and I also appreciated the slower, quieter pace that emerged when she was with her mom.

And, I was surprised by how readily Rosena’s mom made room for me. I never felt like I had to compete with her for Rosena’s affection, respect, or attention. I never felt judged for my slipups and failings, which I tried to candidly share in long, detailed reports about Rosena’s time with us. From the beginning, Rosena’s mom welcomed me onto Team Raise Rosena. Am I ever proud to wear that jersey!

Her mom celebrates holidays and birthdays with us and Rosena appreciates seeing us all interact with compassion, respect, and warmth. We do not always agree, and there have been some tough episodes, but all Rosena sees is her family working together to figure it all out. I love this girl with a boundless and joyful heart. I see so much of my husband in her. I never questioned who I was to her and I never worried that she did not love me. I was, from the beginning, Rosena’s “My Frida,” and that moniker means the world to me. It was totally new and foreign, and yet it felt like home. I can be impatient, she can be heedless. I can be sharp, she can be stubborn. But we are always both learning how to be together.

When I gave birth to Seamus, I took on a new role with Rosena, as the mother of her little brother. Now I am the mother of her little sister too. I have three children half of every week and two children all the time.

And it is a challenge. I struggle with how to be present to the needs of three very different ages and personalities. When Rosena is at our house, Seamus wants to be wherever she is and be doing whatever she is doing. She relishes his attention and adoration, but tires quickly of his grabby-ness and wrecking-ball energy. I welcome the breathing room that comes when he transfers his affection from me to her, and I try to get as much done as I can while he is shadowing her every move. Although Rosena is a conscientious big sister, she is only seven and I need to remind myself sometimes that she is not capable of taking care of Seamus for long stretches of time. She can play with him while I wash dishes or get dinner started, and she loves it, but I can’t put her in charge of him.

Rosena and I have been practicing “ask for what you need.” She has gotten good at telling me and her dad when she needs some time away from Seamus. We respect and honor that, and we know that this skill will help our whole family for years to come.

Sometimes I worry that I parent Seamus and Rosena differently. Am I more indulgent of Seamus? Am I too strict with Rosena? And then I remind myself that Seamus is a toddler; his needs are very different than those of a second grader. I cannot reason with Seamus, I cannot lecture him, I cannot even discipline him. This is the time for teaching, not punishing. Rosena is working to understand that you can’t put a toddler in time-out. I tell Rosena that Seamus learns as much (or more) from her as he learns from me, even though I am with him more than she is. He watches her so closely, loves and admires her so keenly. That is a gift, I tell her, but also a responsibility. It means she shouldn’t tease him or use her bigness against him. I could probably do a better job of setting this example for my kids, of not using my own bigness against them. For the most part I think I do a good job as a parent. But sometimes I fail. Sometimes I really blow it. Sometimes, the only thing I can say is, “I am so sorry. You did not deserve that, and grown-ups are not supposed to do that.”

One day when he was about fourteen months old, Seamus was following me around on the second floor of our house. I was focused on completing some household chore, but he kept crying and whining for my undivided attention. He wanted me to sit cross-legged with him in my lap and read My Family Loves Me eight or nine times in a row. I had already explained to him in my calm, rational mommy voice that I would read to him as soon as I finished folding the clothes. He did not understand. He never understands. I took a sip of water. He whined for the water. I offered it to him. He pushed it away. I poured it on his head.

For a second, I felt awesome and in charge. His eyes got big, he sputtered, and then he started to cry. To cry for real. Not a “Mommy, read to me” kind of cry, but a “Why am I all wet and soggy and cold?” kind of cry. I felt so stupid and weak. Not only was he really mad now, but the floor was soaked, he needed a whole new set of clothes, and I was the bad mommy who reacted to being provoked by pouring water all over her one-year-old’s head. I got Seamus into dry clothes, wiped up the mess, apologized to my little son, and spent the next hour reading to him surrounded by half-folded clothes and other incomplete household projects. He had my chastened, loving, and undivided attention. I made sure that I told Patrick and Rosena that story. But when I told her, I made it sort of funny, trying to embed a lesson in it about how big people should not do mean things to little people just because they can.

This leads me to my second confession. One Saturday morning, the whole household was getting ready for soccer practice. Rosena was dressed in her soccer outfit, and so I told her to spend the next few minutes putting her clean clothes away. I typically do all the laundry and deliver a basket of folded, sorted clothes to her room. One of her chores is to put all her clothes away. Not too much to ask, but she often needs many reminders.

Patrick was getting ready, and I was busy putting warm clothes on Seamus.

“Hey Frida,” she said from the doorway. “Want to see something cool?” I did not even look up. “Are your clothes all put away?” I asked with an edge.

“No, I haven’t started yet.” I saw red. Too much red for the situation.

“Get going with it, Rosena,” I said as I finished getting Seamus ready. Then I went into her room, where she was going through the motions of her chore without any enthusiasm. I thought about how much of my work goes into the little work she has to do: bringing the laundry down two flights to the basement, hauling it in and out of the washer and dryer, and then carrying it back up two flights of stairs—folded and sorted—to her room. All the while, keeping Seamus relatively happy and alive. I thought of all this and I got mad.

“I should not have to remind you to do this over and over, Rosena. I should not have to beg you to put your clothes away. I do so much work and you only have to do this one thing. You know what? Next time I am not going to fold it. You will have to fold it all yourself. How would you like that?” My voice was too loud. I was angrier than the situation warranted. I was feeling unappreciated.

That could have been it. All parents raise their voices and get a little shrill on occasion, right? But no, I went one step farther. I pulled half a dozen articles of clothing out of her laundry basket, shook them free of their folds, and threw them on the ground. “In fact, you fold it now. You do it.” And I walked out of the room as Rosena started to cry. I wasn’t halfway down the hall before I knew I was wrong. I knew I needed to go back into her room and apologize. But I also knew I needed a few more minutes of distance and the calm perspective of my husband. I knew that if I went back immediately, I might get even madder at her for crying.

“I got mad, Patrick,” I told my husband. “I got mad and I crossed the line.” He did not tell me I was a terrible mother, which was really nice of him. He said he thought that Rosena wasn’t really trying to get out of doing the chore; she was just distracted by her excitement at showing me the cool thing. He asked how I felt as I was throwing the clothes. I told him I felt like I had all of her attention, which felt good, but that I didn’t know how to uncross the line I had crossed.

My husband isn’t just a good father and an amazing partner, he is also a younger brother, and that gives him a certain perspective that I—as the eldest of three—do not have. “Did throwing the clothes feel like a big sister power play?” he asked.

Oh man. I was busted. “Yes, I have been right there before. I have done things like that to my brother and sister. Oh jeez. I am such an idiot.”

“You are not an idiot,” he said. “You are great. You are trying. Go and tell her you are sorry.”

It was a long way back upstairs. Rosena had put all the clothes away and was sitting in her room—glum and small. I asked her why she had cried.

“Because I felt like you were being mean,” she replied.

“You are right. I was mean and I am really sorry. I was mad and I should not have been mad. I felt like you didn’t appreciate my work and that is not fair. You were excited about the Lincoln log thing and I want you to share your excitement with me all the time—even when it is chore time. I am really sorry. I should have acted more like a grown-up and less like a mean, big kid.” I kept talking. I told her that I acted like an evil big sister drunk on power instead of acting like a parent who takes advantage of every opportunity to model good behavior and impart valuable moral lessons. Then I launched into a long soliloquy about how being an adult means that you should be able to pay attention to more than one set of emotions at a time, yours and other people’s. You must keep all of that in perspective, and understand where your own anger and frustration come from in order to take responsibility for them. I talked for a long time. I couldn’t help it. “Do you understand all that?” I asked.

“No,” she said, her lovely little face wrinkled with concentration and confusion.

“Don’t worry about it. Sometimes I just need to talk. I am sorry. Do you forgive me?”

“Yes,” she said simply and emphatically. I am a lucky stepmom. Then she told me that during sharing circle at school she said that her chore was putting her clothes away, but that one boy said his chore was watching TV. We laughed together at that.

Once they were off to soccer, I tried to reflect on how to become a better parent. I needed to have patience with my kids and myself, and learn not to take things personally. Rosena was not being disobedient, she was being distracted. I need to work on creating a household culture of gratitude and appreciation through modeling that with Patrick. I also need to understand that my maternal habits come from my own upbringing, my role as a daughter and as an eldest sibling. I also know that I am going to have to say I am sorry again and again and again—to Seamus, to Rosena, to Patrick, and to myself.

The biggest lesson I took from this, however, is that you don’t have to call your kids names, or hit them, to be violent. Blame, retribution, shock tactics, yelling, disproportionate consequences, diffused anger, misplaced anger, and scary, out-of-control anger are all just as bad. In both of these cases, I felt like I did violence to my kids. I used my power against them instead of using my size to protect and educate them.

It comforts me a little to realize that not everything happens all at once, that life is long, that we are all growing and changing every day and that I can’t do it all on my own. I also realize that Patrick’s help is essential, as is asking each other for help. I could do a much better job of realizing that I can’t do this all on my own.

Since Seamus was born, I have hurt my back three times. Three times Patrick stayed home from work for as long as he could and then arranged for his parents and sister and brother-in-law to come and hang out with Seamus. They did things like lift him into his high chair or changing table and carry him up the stairs. I could not do any of that on my own.

It was hard—hard to admit that I needed help, hard to allow myself to be helped, hard to see other people, even family, doing what I thought I should be doing. But it was also an important lesson every mother needs to learn at some point: I am not the only one who can take care of Seamus. He needs and loves other people, and that is a good thing.

Seamus and I traveled to Baltimore once on the train before Christmas. While I was in the bathroom at the train station in Connecticut, Patrick asked a young preppy guy to help me with my bags because he couldn’t stay with us until the train got there. When the train was announced, this guy came over to me, picked up my suitcase, and followed me to the train. Turns out he went to Connecticut College, was a business major, and was hoping to get a job at Lockheed Martin upon graduation. His dad worked there. I had lots to say about that, but it is hard to lecture someone about the merchants of Death when they are carrying all your bags.

At every juncture of that trip (and the many others I have been on), people asked if I needed help. I mostly said no, even when their help would have made getting from point A to point B easier. Do I want to sit down? No thanks. Why? Why say no? What am I trying to prove?

On an airplane a year ago, I carried Seamus to the back when I could no longer ignore nature’s call. I did not have a plan. “Do you want me hold him while you go?” the flight attendant asked. “Yes please! Thank you!” I do need help. I can’t get everything done that I want to get done.

It would be different if I had a job to return to—finding childcare would have been automatic, a necessity, a non-issue. It would have happened months ago—most women are lucky to get three months maternity leave before they have to go back to work—and it would have cost a lot. A 2013 Census Bureau report found that childcare costs have more than doubled since 1985. The average family with a working mother and a child under fifteen pays $143 a week for childcare, a whopping $7,400 a year. Despite these sharp increases in costs, the wages for most childcare workers have not gone up. The report also found that because childcare costs are so high, kids are spending more time unsupervised. Not just teenagers, but even five- to eleven-year-olds. I don’t have a job, but I do have commitments. So far, I have mostly done my work during Seamus’s naps, or on walks, or while Seamus has been engrossed in the serious work of being a baby—moving blocks from one place to another, pulling books off the shelves, pulling all of his pants out of the drawer, playing with the Velcro on his diaper until it fails and he is diaper-free.

But there are times when that doesn’t work and I can’t just say that the baby ate my homework. Nevertheless, we can’t pay $143 a week for daycare so that I can be a good board member at the War Resisters League.

There are lots of options out there that don’t require $143 a week. Patrick and I both played in babysitting cooperatives when we were little, where parents took turns watching each other’s kids. We are doing a date night kid pile with two other couples. One family hosts and the two other couples drop off kids and have a few hours of grown-up time. The kids love the critical-mass playtime and the hosting parents just roll with the chaos for a few hours, dreaming about the two dates they are earning in the process. It is the beginning of creating something new, free, and community-building.

![]()

Back when I lived in Brooklyn, I commuted to work on my bike. Once I passed my mid-twenties, I spent a lot of that time imagining how little my life would change when I had a baby. I was living in Red Hook, a neighborhood that was rapidly gentrifying but still quite poor. I imagined myself riding the same route, the same bike, with a baby somehow safely stacked on top. I was already carrying a lot of stuff with me—work clothes, gym clothes, books, lunch. I could cram diapers, fresh outfits, toys, and all the other things that a baby needs into my overflowing panniers. As I cycled and imagined, I saw toddlers and little kids riding with their parents, mostly European-style in front, mostly with their dads.

Sitting in my office, typing away, answering calls, I would imagine where I would put the baby bassinet and bouncy chair. I worked in SoHo for the Arms and Security Initiative at the time, a progressive think tank where I did research, writing, and resource development about military issues. My office was just my boss and me. In my imagination, my future infant would sleep in the bassinet, and then I would nurse him or her, and then they would play in the bouncy chair while I came up with new ways to argue for a common-sense foreign policy in which the use of force was a last resort. “Perfect,” I thought. “Totally doable.”

At the time I was living in a series of dingy, neglected, periodically rat-infested apartments with a partner who worked incredibly long hours during the week and large portions of every weekend, and who was constitutionally unsuited for—and adamantly uninterested in—fatherhood. We struggled financially despite having good incomes. Despite all of this, I saw a baby fitting seamlessly into our lives. It wasn’t that I wanted to “have it all” in an ambitious, striving kind of way. It was that I assumed that I could have a child—children even—without my life changing at all.

At some level, it is not so strange that I should think kids could seamlessly integrate with my life. That is how my parents dealt with the surprise of children. Pack the bottle and keep on going to meetings, demonstrations, and to the courthouse. All our family photos from our early years are pictures snapped at demonstrations. There are no portraits taken against fall foliage backdrops at Sears, there are no photographs where we all cozy up near the Christmas tree with mugs of steaming cocoa in ironically awful seasonal sweaters. We did not go to Disney World or water parks or the zoo or baseball games or on vacation. The Berrigans didn’t do stuff like that. We resisted.

Here is how my birth was announced in my parents’ book The Time’s Discipline:

Throughout Lent of that year, [we] mounted a series of direct actions connecting the war in Indochina with North America’s support of tyrants abroad and with the war against the poor at home. [Chilean president Salvador] Allende had been assassinated with CIA and NSA support. This we exposed in the only demonstration held at NSA headquarters. Holy Week brought the first action in which actors faced serious consequences (longer jail terms) at the Vietnamese Overseas Procurement Office. Holy Week also brought the birth of Frida Berrigan, our first daughter.

Here is what they say about Jerry: “The ouster of American troops from Indochina in April 1975 coincided with the birth of our son, Jerome, and with the initiation of our community’s anti-nuclear work.”

It is not that our parents were not overjoyed that we burst onto the scene. But as they celebrated, they bundled us up in the back of the old Volvo sedan and kept on going. As Dad wrote, it is

for the love of children that community gathers its witness again to speak publically of truth, sanity, and compassion against a public scarred by a militarist spirit, and a state mad with corruption and blood lust. Liz and I have pain, inconvenience [when in jail and away from the kids]. But what is it next to the pain of those in the Ukraine or Armenia or Indonesia or El Salvador or wherever the superpowers grind their iron heels?

The fact that I was raised on the picket lines is not the only reason I felt compelled to shoehorn kids into my frenetic and ungrounded New York City life. Like most women, I believed that the older I got, the harder it would be to have children. No wonder I fantasized about baby-bike commuting and a new life that did not upend my old one. I was afraid to wait.

An article written by Jean Twenge in the July/August 2013 issue of The Atlantic Monthly challenges the prevailing wisdom on declining fertility:

The widely cited statistic that one in three women ages 35 to 39 will not be pregnant after a year of trying, for instance, is based on an article published in 2004 in the journal Human Reproduction. Rarely mentioned is the source of the data: French birth records from 1670 to 1830. The chance of remaining childless—30 percent—was also calculated based on historical populations.

In the article she talks about how “baby panic” leads women to have babies with the wrong guy, to turn down career opportunities, and to have kids before they are emotionally ready. And all this worry is “based on a few statistics about women who resided in thatched-roof huts and never saw a light bulb.”

In a recent study of modern women, Twenge goes onto note, “the difference in pregnancy rates at age 28 versus 37 is only about 4 percentage points. Fertility does decrease with age, but the decline is not steep enough to keep the vast majority of women in their late-thirties from having a child.”

Sure enough, when the time and the man were right, I got pregnant right on schedule—four months after our wedding. And a month and a half before I turned forty, we had another one!

Commuting five miles by bike with an infant in New York City? I am sure someone does it. My hat is off to them, but I was barely brave enough to bike solo around the city, and I had my fair share of scrapes and scary moments and two relatively serious accidents. Seamus was six months old before I got used to driving with him in the car. And I still don’t like it. I would rather walk: no matter how hot the weather and how heavy the kid—nothing about getting a baby in and out of a car (or a bike seat) is easy.

When Seamus was an infant, I could—if I planned everything just right—type for twenty or thirty minutes at a stretch while he nursed and slept. Through diligent time management and with lots of support and flexible deadlines, I managed to write my column for Waging Nonviolence more often than not. But I did it in the comfort of my own home, spread out over three rooms, wearing sweatpants and completely on my own schedule. I never stopped to consider what would have happened when my imaginary New York baby developed a mind of his own, an appetite for power cords, and a very loud voice. When Seamus was a year old he barely napped and didn’t spend all that much time alone. Writing involved a lot of wrestling the pen, the mouse, the paper, the keyboard out of his hands, being a skillful distractor, and making use of the early-morning and late-night hours.

Babies do not fit neatly into our lives; they turn our lives upside down and insist that we do everything differently. The challenge is to see that as a gift, an opportunity, and a new beginning.

![]()

And then another new beginning. Madeline Vida Berrigan Sheehan-Gaumer.

Before we were married, Patrick and I used to talk about having five kids—at least five. That makes us laugh now. We have a big house. It was a foreclosure that was empty for at least two years. The former owners installed a Jacuzzi bathtub but neglected to repair the roof. We bought it for less than some people pay their nannies. It has four bedrooms, a little study, a full attic, a full basement, a nice yard, and a back and front staircase. We thought we would never fill it—not even with five kids. But now it is full, and Madeline and Seamus will have to share a room if we want to keep a guest room.

Still, this is not the worst problem in the world. There are more than seven billion people on Earth today, with another 375,000 born every day. The United States is the third most populated country in the world and although China and India have more people by several orders of magnitude, each U.S. citizen out-buys, out-eats, and out-drives each Indian and Chinese person by several orders of magnitude.

Overpopulation keeps a lot of scientists and policy makers up late worrying about the global food and water supply, deforestation, and global warming. Today, hundreds of millions of people are hungry and tens of millions do not have regular access to an adequate supply of clean drinking water.

Like Western Europe and other developed countries, we have a relatively low birth rate in the United States. Until recently, immigration kept us from noticing that fact, but a December 2012 report from the Pew Research Center found that “immigrant births fell from 102 per 1,000 women in 2007 to 87.8 per 1,000 in 2012, bringing the overall U.S. birthrate to a mere 64 per 1,000 women—not enough to sustain the current U.S. population.”

The pressing issue in this country is not too many births, but too many unintended births. Nearly half of the births in this country are unplanned and unwanted. In 2006, the last year for which I could find full data, at least half of these pregnancies ended in births at a cost of more than $11 billion a year to taxpayers.

As a mother who loves her kids, I worry over their future. What will the world look like when they come into their own? What issues and problems will they face? What can their dad and I do to prepare them? And, the most fundamental question of all: is it right to bring more children onto a planet that cannot provide for all the people who already live here?

We are trying to raise our kids to be people who will consume fewer raw materials, not agitate for war, and help foster resilient and sustainable communities of people. Hopefully, they will play a part in resolving, rather than exacerbating, the problems of the world. But all of that can wait for now. When I found out I was pregnant again at thirty-nine, despite sustaining a voracious nursing toddler, I just cheered. Hurray, I am pregnant! Pregnant and strong!

Five months pregnant, I walked to the grocery store, a two-mile round trip, pushing Seamus in the stroller and moving rather fast. On the way home we were weighed down by a gallon of milk and other groceries. It was a lovely fall day, and he slept the whole way, his hand stuck in a cup of Cheerios. In the afternoon, I transplanted hostas, pruned bushes, and got the yard ready for the winter while Seamus and his dad and big sister visited their grandparents and watched baseball. At the end of the day, I felt a little tired, but also like a lot had been accomplished.

Examples of strong, pregnant woman are everywhere I look. A friend from high school ran a marathon six months pregnant. My sister-in-law, Molly, did a major relay race four months pregnant. I loved running with her when she was seven and eight months along because I could sort of keep up. Amber Millar and her husband ran and walked the Chicago Marathon in 2011 and then headed straight to the hospital afterward, where she gave birth seven hours later. She told the Chicago Sun Times that “the race was definitely easier than the labor.”

Nur Suryani Mohd Taibi competed in the Olympics eight months pregnant. But she wasn’t going “coast to coast” on the court, pulling a triple lux on the ice, or sprinting to the finish on the track. She was a sharpshooter for Malaysia. She didn’t advance beyond the first round, but she was the most pregnant Olympian in history. She told her unborn daughter not to kick too much while she was competing: “I told her, ‘OK, don’t move so much, behave yourself, Mommy’s ready to shoot, help Mommy to shoot.’”

Athletes, politicians, performers, normal Janes: women get pregnant. Model Alessandra Ambrosio hid her pregnancy so she could walk the catwalk for Victoria Secret in 2011. She looked great (in a Victoria’s Secret sort of way). She was two months pregnant and hit the gym hard for the few weeks beforehand.

Raquel Batista isn’t hiding. The lawyer and community organizer from the Bronx ran for New York City Council and gave birth to a baby girl in August. Sally Kohn of The Daily Beast asked if there is a “broken-water” ceiling where women are penalized by voters for being pregnant. Kohn wrote that throughout her campaign, “Batista’s pregnancy was never seen as a positive—a sign that if she would fight this hard to get into office while pregnant, imagine how hard she would fight for her constituents while in office.”

The strangest thing about being pregnant is how conspicuous you are—how often strangers talk to you and ask you questions. It is like wearing a big sign all the time, in a good way. My experience is that pregnant women make people happy. We are visible, so we might as well make the most of the nine months. The fact that pregnant women are running, rapping, dancing, giving speeches, and wielding paint brushes on top of step ladders helps to put to rest the enduring sexist notion that pregnancy is a malady, weakness, or condition.

We resist—with our brawn, bulk, and hormones—patriarchy’s compulsion to shut us away to worry over the nursery and do kegels. We are here and we are growing the next generation: get used to it and get to work making the world worthy of our children.

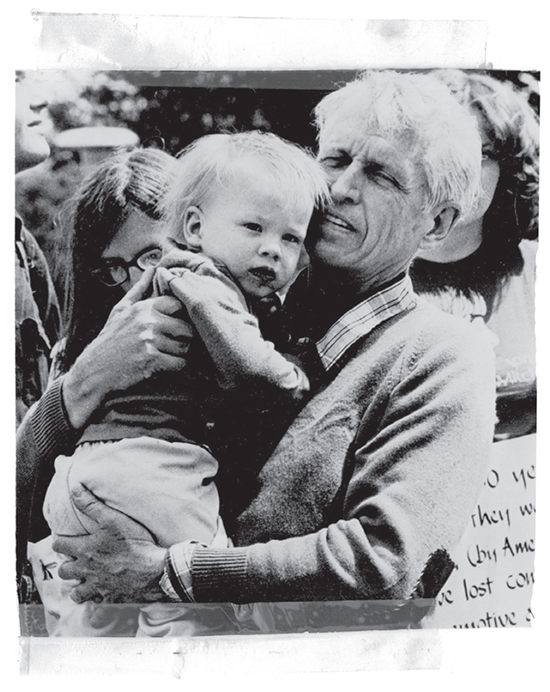

Frida and Phil Berrigan at the Pentagon, 1976.

Frida and Phil Berrigan at the Pentagon, 1976.

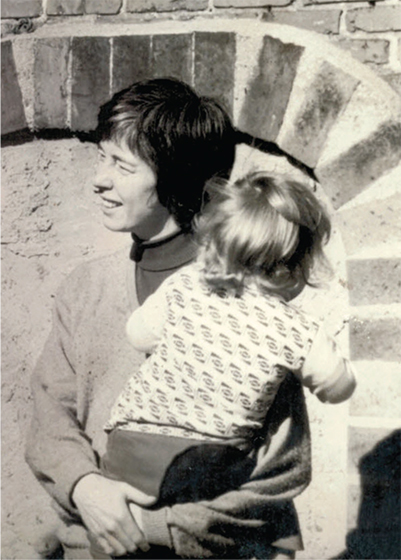

Frida and her mother in the backyard at Jonah House.

Frida and her mother in the backyard at Jonah House.

Young Frida protesting, possibly at the Department of Energy.

Young Frida protesting, possibly at the Department of Energy.

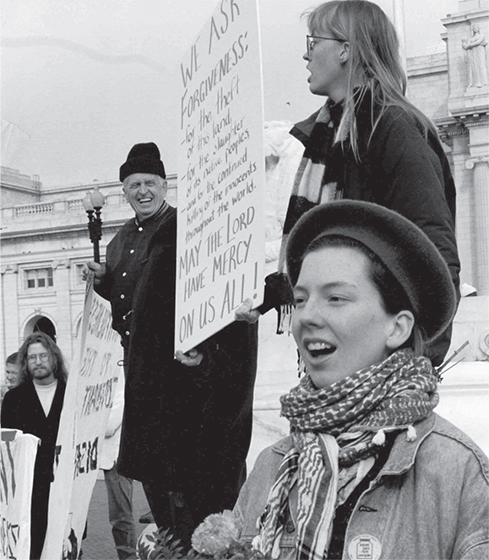

Singing at a Columbus Memorial, October 1992. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: Bruce Friedrich; Phil Berrigan; unidentified woman; Frida Berrigan (in the hat).

Singing at a Columbus Memorial, October 1992. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: Bruce Friedrich; Phil Berrigan; unidentified woman; Frida Berrigan (in the hat).

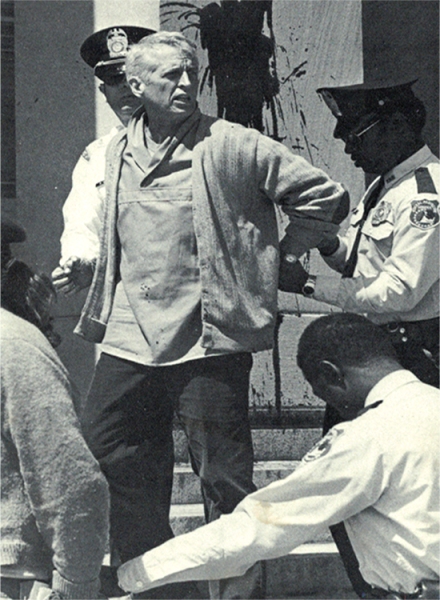

Phil Berrigan being arrested at the Pentagon, Riverside entrance, blood on the pillar behind him.

Phil Berrigan being arrested at the Pentagon, Riverside entrance, blood on the pillar behind him.

In front of 1933 Park Avenue, Jonah House, with some of our community, taken while our mother was in Alderson prison in West Virginia. The whole width of the house is shown—14 feet. The sign on the window reads “Nuclear Free Zone.”FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP ROW: Jerry Berrigan; neighborhood friend; Greg Boertje, now Boertje-Obed, serving a 5 year prison sentence for the Transform Now Plowshares action, Tennessee, July 2012; Mary Loehr, holding Gandhi poster, now part of the Ithaca Catholic Worker.MIDDLE ROW: Ellen Grady, wearing black, now part of the Ithaca Catholic Worker, with her arm around me. BOTTOM ROW: Brian Barrett, lives in Baltimore and remains part of the Jonah House extended community; Ellen’s husband Peter DeMott, now deceased; Kate Berrigan.

In front of 1933 Park Avenue, Jonah House, with some of our community, taken while our mother was in Alderson prison in West Virginia. The whole width of the house is shown—14 feet. The sign on the window reads “Nuclear Free Zone.”FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP ROW: Jerry Berrigan; neighborhood friend; Greg Boertje, now Boertje-Obed, serving a 5 year prison sentence for the Transform Now Plowshares action, Tennessee, July 2012; Mary Loehr, holding Gandhi poster, now part of the Ithaca Catholic Worker.MIDDLE ROW: Ellen Grady, wearing black, now part of the Ithaca Catholic Worker, with her arm around me. BOTTOM ROW: Brian Barrett, lives in Baltimore and remains part of the Jonah House extended community; Ellen’s husband Peter DeMott, now deceased; Kate Berrigan.