Manage Your Pain: Practical and Positive Ways of Adapting to Chronic Pain - Michael K. Nicholas, Allan Molloy, Lee Beeston, Lois Tonkin (2012)

Chapter 7. Using Pacing To Overcome The Effects Of Chronic Pain on Activities

Earlier, we described some of the ways in which chronic pain can affect your normal lifestyle. This section will have a closer look at some of these effects and how you can overcome them.

A key strategy is to use activity pacing.

Chronic pain usually leads to changes in people’s activities and the way they do things. These changes will vary from person to person, but a typical list would include the following:

· give up working or work on restricted duties

· do less housework or home-maintenance work

· overdo things (push yourself), then have to rest

· do fewer enjoyable activities

· do fewer social activities

· avoid trying new activities

· rest or lie down more often during the day

· take pain killers (or tranquillisers or sleeping tablets as well)

· develop sleep problems

· drink or smoke more

· avoid people or certain activities

· have more conflict with family members and friends

As time goes on, these changes can start to become habits - you can feel as if you are in a rut. By then it can seem almost impossible to do anything about it.

These changes come about in many ways, but a common story from people with chronic pain is that they push themselves until they feel the pain tells them to stop. Then they rest, possibly take one or two painkillers, and wait for the pain to ease.

After a period of rest the pain may ease a little and then they will get up and try again - only to find the same thing happening again (more pain, stop, rest, try again). After repeating this pattern over and over, they may also start to get frustrated at not being able to do many of the things they used to do quite easily. Eventually, this can lead to feelings of despair and to wondering if they will ever get on top of the pain.

You may also start to feel as if the pain is running your life. In fact, many of our patients with chronic pain say that the sense of loss of control over daily life is one of the worst things about chronic pain.

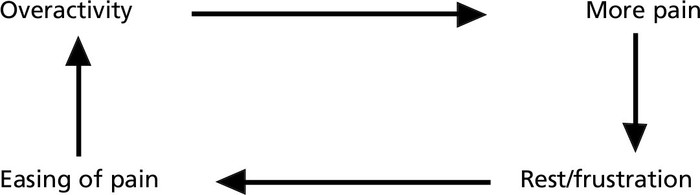

The diagram below summarizes a common picture that many people with chronic pain report.

A Common Pain—Activity Interaction

This pattern of ‘overactivity-more pain-rest/frustration’ can happen on both a daily basis and a weekly basis. For example, you may find you have “good days” and “bad days” (good days are when the pain is not so bad and bad days are when the pain is worse). What can happen in this case is that you will overdo things on the good days (perhaps trying to make up for lost time), but because of your lack of fitness you will strain your body, the pain will worsen and you will then spend the next day or two resting again (making yourself even more unfit).

Each episode of increased pain makes it more tempting to avoid doing activities which result in more pain. Over time, reduced activity (excessive rest) will cause the body to lose condition, with joints becoming stiffer and muscles becoming weaker. It might interest you to know that research by scientists working for the United States space programme has shown that even a week of rest can result in measurable loss of physical condition - even in healthy astronauts.

As your body loses condition it will gradually become less able to cope with a higher level of activity. Over time, less and less activity will be needed to overdo things. Rest or low activity periods tend to become longer, and total daily activity tends to get less and less - despite occasional bursts of high activity (which, of course, may end up causing more pain and then more rest).

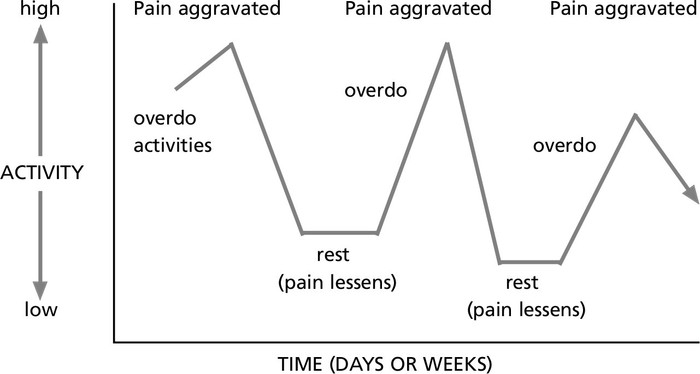

The diagram below describes this common pattern of behaviour amongst people with chronic pain. It might be described as a life of “mountains and valleys”.

Overactivity/underactivity cycle

A classic example of this was provided by Ray who was determined to keep going with his old lifestyle, but this had still led to a “mountains and valleys” existance. On the ‘good’ days when Ray’s pain was less, he got stuck into all the activities he couldn’t manage when his pain was more severe. However, by doing more than he was used to his pain was stirred-up later in the day. The following day his pain would still be worse, so he would spend the day resting and doing very little, much to his annoyance and frustration. After a day or so like this, his pain would start to settle again and the pattern would be repeated. When asked what he thought about his approach, Ray said that he wasn’t going to give in to the pain and he didn’t want anyone to think he wasn’t trying. But he also had to admit that his approach to beating the pain wasn’t working and he was willing to see if there could be another way of dealing with it.

What sorts of effects can inactivity have on our bodies?

Naturally, this will depend on how long we are inactive and how little we do. Our bodies have a tendency to respond to the demands placed on it. Most of us have heard the saying “Use it or lose it!” This could apply to the risks involved in disuse of the body.

In a surprising short time too much rest can have quite marked effects on our body. We all know how unfit we feel for regular work when we’ve had even a week off. Most of us also feel quite out of condition at the start of summer when we want to get into shape for wearing swimming costumes again.

Did you know that too much rest can have these effects?

✵ An increased risk of developing heart conditions

✵ Obesity

✵ Weakness of the bones and wasting of the muscles

✵ Depression

✵ Premature ageing

Let’s have a look at the effects of disuse on the main systems in our bodies.

Muscles and Tendons: A decrease in the thickness of the fibres occurs, and the tissue becomes more fibrous, causing it to become more painful when stretched. 8 gms of protein is lost per day with bed rest.

Joints: The cartilage in the joint, which normally acts as cushioning for the joint, becomes dried and breaks down. The capsule around the joint becomes tight and the joint loses stability due to weakness of the muscles around the joint.

Bone: With each week of bed rest, 1.54 gms of calcium is lost. After 6 months of complete bed rest, 40% of the body’s calcium is lost. The bones rely on calcium for their strength. Loss of calcium causes the bones to become brittle and at increased risk of breaking.

Cardiovascular: This refers to the heart, blood vessels and lungs. The heart is a muscle, and if it is not exercised, it becomes smaller and works less efficiently. When you exercise, your muscle need more oxygen to cope with the increased muscle activity. The way the oxygen gets to the muscle is in the blood, via the blood vessels. The heart acts as a pump, firstly to pump the blood to the lungs to pick up some fresh oxygen and get rid of the waste products, such as carbon dioxide. The heart then continues pumping the blood around the body to wherever the oxygen is needed. Naturally, all parts of the body need oxygen to keep alive. At rest, the heart can pump enough oxygen filled blood around the body to satisfy the body’s needs without too much effort. When you start exercising, you need to get more oxygen to the exercising parts. For this to happen, the heart has to work harder, the lungs have to expand more, and the blood vessels become more flexible.

Being inactive prevents all these cardiovascular mechanisms working properly.

|

As a result, |

✵ |

the heart muscle becomes smaller, |

|

|

✵ |

there are increased fatty deposits around the heart and vessels, |

||

|

✵ |

less volume of blood is pumped out of the heart, |

||

|

✵ |

the resistance in the blood vessels increases, causing high blood pressure, |

||

|

✵ |

and the size of the red blood cells decreases. This means less oxygen can be carried around the body and you are likely to feel more tired. |

||

|

Brain: |

✵ |

the circulation to the brain decreases causing reduced oxygen, |

|

|

✵ |

signs of tiredness and reduced alertness occur, |

||

|

✵ |

sleep becomes disturbed, |

||

|

✵ |

inability to cope with stressors increases, |

||

|

✵ |

and increased susceptibility to depression develops. |

Genitourinary System: the kidneys become smaller because they do not need to filter as much waste product, and the bladder becomes smaller because it does not need to store as much urine.

Sensory: Bed rest has been noted to result in reduced sharpness of sight, hearing and taste. Balance mechanisms can also be affected.

All these effects have been demonstrated in people who have developed what some have called “the disuse syndrome”.

Of course, no person with chronic pain will develop all these problems. But the list is a reminder of what can happen to all of us if we become too inactive. The list of effects should also remind you that not all your physical and emotional symptoms are due to whatever has caused your pain. They are not all a sign of underlying or undiagnosed injury. Rather, many may be result of the way in which pain has changed your normal lifestyle. The good news is that these effects are reversible - by your becoming more active again.

It is also true that not all people with chronic pain get into a pattern of overactivity and underactivity, but most will find they do less when the pain is worse and more when the pain is not so bad. If this is the case, you will still find that the pain disrupts your normal activities, even when the pain is not so bad. As time goes on the long-term effect on your body will still be a gradual loss of condition.

Why do people stay in this activity/pain cycle?

While most people will say they can see this pattern of activity is self-defeating, they find it hard to get out of it. After all, they can see how important it is to keep active and to lead as normal a life as possible - it’s just that each time they try, the pain stops them.

Some people say they can’t stop because they have no choice (eg. due to family or financial concerns). Others say things like: - “it feels better to finish the job” or “activity is often enjoyable, and it helps to distract me from the pain”. Perhaps you will recognise some of these views from your own experience?

Other draw backs to the activity/pain/rest cycle

Besides leading to a gradual loss of physical condition, overdoing things then resting too much, then overdoing things again can lead to a number of other problems. These include:

- flare-ups in pain severity (which can last from hours to days)

- pain decides how much you do, not you (you don’t feel in control of your daily life)

- it gets difficult to plan ahead because the pain might play-up

- working at a regular job is harder

- you can start to feel that you’re never getting anywhere (and end up with feelings of frustration, failure, and even depression)

- having the pleasure of achieving something reduced by the pain.

How can you break the activity/pain/rest cycle and still keep active?

If you think you get into these patterns of doing too much/getting more pain/having to rest what can you do about it? Clearly, the first step is to realise that you do it. Then you should try to work out why you do it - perhaps some of the reasons mentioned above will be familiar to you?

Whatever the case, there are ways to increase your activity level, without stirring up the pain too much. So that you can once again enjoy a wide range of activities. Naturally, some activities will take longer to achieve than others. Realistically, you may have to accept that some are impossible. In these cases, you will need to look for alternative options or decide on your order of priorities. For example, if you can’t do everything you’d like to do, then which activities can you drop for now? Remember, you may be able to get back to them at a later stage.

But if you stick at it, you can achieve a great deal. It is likely that even your doctors may not be able to accurately predict what you will achieve in the long run. For example, Jackie, one of the graduates of our programme had as one of her goals returning to work as an aerobics instructor. We felt this was unlikely and that she should set her sights a bit lower. However, she stuck at it and a little under a year later she wrote to us to say that she had achieved her goal. Her own words describe it best:

“I had been an ultra fit 21 year old jumping around, teaching aerobics, jogging 14 kms, weight and gymnastic training my days away, until one night I was injured while training. Having the mentality of a dancer, I pushed myself through am amazing amount of pain to keep going, so far in fact that I ended up bedridden for 2 whole years, experiencing constant pain down both legs to the ankles.

I was so desperate for a cure that I went everywhere, saw everybody, had 2 operations - both unsuccessful. The pain was enough to make me faint some days. I lost all muscle and went down to weighing just 36 Kg. Everyday was like living with the drip, drip of water torture. I was so depressed and in complete despair. I was in tears every day for 8 months. Things could not have been worse. I really believe no matter what lies ahead for me it will never compare to what I suffered.

After almost 2 years like that I attended the ADAPT program at RNSH Pain Management Centre. I was not confident that it would help and fought all the way about going. BOY WAS I WRONG !!! What a godsend the program has been. The commonsense approach to dealing with a chronic problem is now present in every moment of my day. It has become a way of life and the results speak for themselves. Not only has it helped me manage my spinal disc problem, but other setbacks along the way.

Now, just 12 months after the clinic, I am back living by myself, doing all my chores and would you believe, also working fulltime as a fitness instructor !!! I’m at university part-time too. Life has never been better.

The pain is still present to this day, but what I learnt through the program has taught me how to manage my life with the pain.”

The key words for changing your lifestyle are:

- plan it - make it gradual - be consistent.

Pacing - an essential technique for mastering chronic pain

The aim of pacing is to maintain a fairly even level of activity over the day (as compared to doing as much as possible in the morning, say, and then resting for much of the afternoon).

There are three main aspects to pacing:

(1) Take frequent, short breaks.

Do something for a set time - then take a short break - then do a bit more - then take another short break - and so on. For example, if you can manage 15 minutes in the garden, but then have to lie down for the rest of the day, try working in the garden for say, 10 minutes, take a 15-30 minute break, then do another 10 minutes in the garden. This way you will do less than you could do each time, but you won’t overdo things and ruin your whole day.

(2) Gradually increase the amount you do.

To begin with, it will seem as if you are going backwards, because you are doing less than before. But once you’ve got the idea of pacing, you can start to gradually do more. To “pace up” an activity you should plan to do a bit more each day or every second day. Each increase should be small and you should not do more than you planned, even if you feel like it. Before long, you will able to do more than before - and without the extra pain you used to get.

For example: To use the gardening example mentioned above, you would work out how much more you could do each day. You may decide to add on one minute more to each session. If so, on the first day you would do two 10-minute sessions. On the second day, two 11-minute sessions, and so on. In this step - by - step way you can slowly increase the time you spend in the garden, without overdoing things.

(3) Break-up tasks into smaller bits.

If the whole task is too much for you to try in one go, try breaking it up into amounts you can manage. For example, do three trips to the shops each week instead of one large buy. Or, divide your grocery shopping into two bags instead of one. As you get fitter and stronger you can gradually do more or carry more.

Guidelines for pacing

The three ways of pacing can be applied separately, but they will often overlap. Pacing should be applied to both exercises and daily activities, such as sitting, standing or walking. Whatever the task, however, you should follow the same basic steps to pacing.

(1) Work out what you can manage now

Once you have decided which activity or exercise you want to build up, work out what you can do comfortably now (without too much extra pain). This may take several attempts over a couple of days - until you are happy that your baseline is about right for you - even when the pain is bad. Try not to compare yourself with others (everyone is different). Most importantly, do not compare yourself with what you think you ought to be able to do (you are trying to work out what you can do now, not at some other time).

With some activities, such as exercises or standing, you can measure what you can manage by counting or timing. In this case, you should try the exercise or task two or three times and make the average your present level. You work out an average by adding the number of repetitions of an exercise and then dividing that total by the number of times you did the exercise. The result is your current average for that exercise. For example, if on the first try you can do 5 sit ups, on the second 7 and on the third 6, the total number of repetitions would be (5+7+6) = 18. You did the exercises on three occasions, so the average for the three occasions would be 18 divided by 3, which equals 6. Your current level for that exercise would therefore be 6 sit ups.

(2) Work out your starting point or baseline

To make success more likely, don’t start pacing up from your current level (that may reflect a good patch). Instead, start just below it - at a level you know you can manage. A starting point 20% below your current level is a general “rule of thumb” we have used successfully. If you are not sure how to work out 20%, just reduce your current level by enough to be sure that you will succeed the first time you try the exercise or task.

For example, using the sit ups example mentioned above, you would set your starting point at 20% below your current level of six. This means you would start at 5 sit ups - which is what you did on your lowest attempt.

Using the gardening example mentioned earlier, you would set your starting point at 20% below the 15 minutes you normally spent in the garden at one time. This means you would start at 12 minutes.

(3) Decide on a realistic build up rate

Most people want to run before they can walk, but you will already know that trying to do too much too soon will make you overdo things. Before long you would be back to “square one”.

You will be more successful if you try to build up your exercise or task slowly to begin with. Later, if you think you could go faster, you can give that a try. But first, build up slowly, then see how things are going.

You should try to build up your exercise or task at a steady rate, regardless of the pain. So, when you are working out your build up rate, ask yourself “will I be able to do that much when the pain is bad?” Of course, if you are too optimistic to begin with, and you set too high a build up rate, you can change it. But you will find it helps your confidence more if you set a rate you can keep up.

For example, using the gardening example used earlier, you might decide you could manage to spend an extra minute in the garden each day. If you started at 12 minutes on day one, on day two you would do 13 minutes, on day three 14 minutes, and so on.

(4) Write your plan down and record your progress

Trying to keep your pacing plan in your head will probably result in confusion and forgetfulness. You will find it helps to write your pacing plan down and to record your daily progress. In this way you will soon notice if you are making progress - or slipping back. Signs of progress will usually be gratifying and confidence building. You might even give yourself a special reward when you reach your goals each week. Signs that you are slipping or not progressing will give you a chance to work out why and what you can do about it.

Additional hints for using pacing

(1) Start on activities that are easier - Be prepared to leave those activities that are too hard for now. You can come back to them later as you get fitter and more capable. Start on activities that are easier. Once you have learnt how to manage them, you will find it easier to tackle the harder activities.

(2) For those activities that you cannot leave - It is most important that you still try to pace yourself as much as possible. Take short rest breaks as often as possible (stretch and relaxation exercises are helpful things to do when you have a rest break).

(3) Try to change your position regularly. For example, whilst preparing a meal, you could try to change between standing and sitting every few minutes, as well as take a short rest break every now and then.

(4) Remember, it is alright to ask for help with specific tasks now and then - everybody does it. People who feel unable to help you with your pain may be glad to be asked to do something they can do.

(5) Keep to your targets and plans as much as possible - This will mean that you (not your pain) decide how much you do. If you are having a bad day, try to keep going as you have planned but pace yourself more (ie. take more rest breaks). If you are having a good day, be careful not to do more than you have planned, to avoid overdoing things.

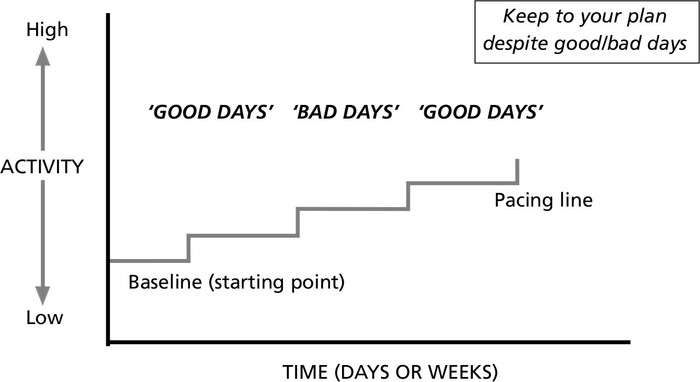

If you follow these guidelines you should have fewer flare-ups with your pain and you should gradually find yourself doing more and more. As the diagram below shows, this approach means doing more on the bad days but less on the good days (so that you avoid overdoing things). Naturally, this all takes quite a lot of discipline on your part. But it will be worth it in the end (which is why it helps to select goals which mean something to you).

Pacing up your activity level (step by step)

As you would expect, progress in this area is rarely “plain sailing”. Set backs or flare-ups will happen from time to time no matter how careful you are. This won’t mean you are back to square one, but how much trouble you have will depend on how you react. We recommend that you read the discussion on flare-ups (Chapter 17), but also discuss it with your doctor or clinical psychologist or physiotherapist.

How far should I go?

This is really up to you. In the end, it depends on what you are trying to achieve. For most people, simply achieving a reasonably balanced lifestyle, between exercise, leisure, work, and family or friends is enough. Others want to excel at something. But there is no point in simply getting fitter and fitter unless it is leading you somewhere. That is why working out your goals is critical.