Four Ways to Click: Rewire Your Brain for Stronger, More Rewarding Relationships (2015)

Chapter 7

R IS FOR RESONANT

Strengthen Your Brain’s Mirroring System

Signs that a relationship is Resonant:

This person is able to sense how I feel.

I am able to sense how this person feels.

With this person I have more clarity about who I am.

I feel that we “get” each other.

I am able to see that my feelings impact this person.

In a classic scene from the movie Jaws, chief of police Martin Brody sits at the dinner table, polishing off a bottle of wine. He rubs his face and his shoulders droop. There is no voice-over to tell me explicitly how Brody feels, but none is necessary. My brain has a mirroring system that takes in the information on the screen; it creates activity in my prefrontal cortex and somatosensory cortex that helps the neurons there internally copy his body movements and messages. The neural input passes through my insula, the little strip of brain tissue that helps connect context with emotions. This system of circuits from across the brain tells me Brody is exhausted and troubled. More than that, he is haunted by his decision to keep the beaches of Amity Island open after the first couple of shark attacks.

I’m not the only one who is mirroring Brody. While Brody is lost in thought, his young son sits at the table next to him, watching. Brody’s son spontaneously imitates his father, rubbing his face as if he, too, were exhausted; he carefully raises his cup for a sip of juice the same way his father sips his wine. After a moment, Brody notices and plays along. He clasps his hands in front of him and then pops his fingers straight out, and his son follows along, pleased to have gotten his father’s attention. The scene ends with a mutual, playful sneer and a loving kiss. Throughout the scene, Brody’s son follows the actions of his pensive dad perfectly and mirrors his glum mood to a T. When they finally make eye contact, it’s clear that Brody has been rescued from the brink of despair, drawn out of isolation into the loving connection with his son. That is the power of relationship and the beauty of an active mirroring system: one healthy connection can stave off the despair of shark-infested waters.

We are built to imitate people. Not because we are unoriginal copycats, but because we are blessed with a neurological system that automatically uses imitation as a crucial component of reading other people’s behaviors, intentions, and feelings. The mirroring system can manifest itself in obvious ways, as when two people in conversation will start to copy each other’s posture. You’ve seen this: one person crosses his legs and then the other crosses his. One leans forward, his chin in hand; the other copies the gesture almost instantly. I once had the strange experience of unintentionally copying George W. Bush. Just after he became president, his face was everywhere—on the cover of magazines, on the TV news, when I opened my Web browser. In most of the photographs, he was wearing that expression in which he appears to be in on a practical joke, like he’s just put a whoopee cushion on his best friend’s chair. For weeks, possibly even months after his inauguration, I would catch myself making the same face. And whenever my face transformed into a likeness of President Bush, his image would pop into my consciousness. The more I mimicked him, the more empathy I felt with him. The mirroring system is what allows us to resonate with other people without having to focus deliberately on the task.

I opened this book by claiming that boundaries are overrated. Resonance is the ultimate anti-boundary; it happens when one person’s actions, intentions, and feelings are instantly, unconsciously replicated in a fainter way inside another person’s brain. This replication is a good thing, because resonance is an important relational skill that lets us feel a deep-in-the-bones connection with others. Unfortunately, the mirroring pathway is the one that’s most neglected when we’re in a culture that emphasizes boundaries and separation.

Like the other C.A.R.E. pathways, the mirroring system is shaped by your relationships. It’s well known that early, attuned relationships between mother and child lead to children who spend more time in social engagement, are able to better regulate their emotions, and are able to interpret and comment on their feelings and internal experiences.1 The discovery that neuroplasticity exists throughout the life span suggests that pathways for connection, including the mirroring system, continue to shift and change in response to relationships. Healthy relationships nurture our neural capacity for resonance. Damaging relationships, especially ones with people who don’t really understand you or see you for who you are, can weaken the neural circuits that are involved in the mirroring process. Those circuits may wither from disuse; they may not get the chance to build a rich neural network that allows for shared information; they may not receive the relational dopamine and other neurochemicals that solidify its pathways.

When that happens, it can be harder for the shared neural circuits that are involved in the mirroring process to imitate other people’s feelings. As a result, you may find other people puzzling. You may think that everyone is blithely content when they are actually trying to send up flares of distress. Or you may be so sensitized to “dangerous” emotions that you overread people as being angrier or more distressed than they really are.

This oversensitization is what happened to Pauline. When I first met Pauline, she was waiting on a bench in the hallway outside my office, looking around nervously. Actually, she was looking for me. I was a few minutes late, and I immediately felt sorry that my tardiness had apparently increased her anxiety.

Most clients feel at least a little normal anxiety when they first see a psychiatrist. Truth be told, first meetings often make me a little nervous, too. I never know what I’m going to hear and learn. But Pauline’s anxiety level was remarkable. When she saw I was ready for her, she turned her head down so that she was looking at the floor. I put out my hand and she extended hers limply, still without looking directly at me. As I said, her case is remarkable. I share her story here because it takes the garden-variety problems many of us have with resonance and magnifies them by a few factors, letting us see our own difficulties with greater accuracy.

As we went into my office and talked about the basics—where she lived, with whom, where she worked—Pauline relaxed a little. I tried not to look directly at her for very long, thinking that I didn’t want to exacerbate her discomfort. When Pauline did look up, I made a point to smile and nod in my most outwardly interested way. Despite my best efforts to be welcoming, when Pauline spoke she often apologized about something she had said. “I’m not giving you the right answers, am I?” she asked. “I think you want more detail than I just gave. I’m sorry.”

The interaction was confusing to me as we stuttered our way through the first thirty minutes. I’m an experienced psychiatrist who can usually get a lifetime’s worth of information from a new client in sixty short minutes, but at this point in the session I felt like an unskilled dancer who kept stepping on her partner’s toes. Pauline talked of feeling anxious much of the time, worried that others were angry or disappointed with her. Her fear with me and the way she described her disappointing and sometimes frightening interactions with other people made me wonder whether Pauline was unable to read friendliness on a face, or if people became frustrated by her inability to stay connected, make eye contact, and stop apologizing.

An answer arrived when we discussed her family history, and that answer loops back to the theme of early relationships that shape the brain. Pauline grew up with a father who’d gone to Vietnam when she was five and came home a brittle, angry man. I don’t intend to point a blaming finger at Pauline’s dad, because his behaviors as described by Pauline are in line with post-traumatic stress disorder—and this was a time when PTSD was barely understood, let alone treated. The mirroring system that helps you automatically connect with others does necessarily turn off in the heat of battle and produce an emotionally disconnected solider. In fact, I often wonder if one of the reasons so many soldiers develop PTSD is that, despite the adrenaline rush of combat, their mirroring circuitry reads the pain of everyone around them, friend and foe alike. That pain is stamped onto the soldier’s nervous system. When the solider goes home, the pain comes along, too.

Life with Pauline’s father was unpredictable. It was hard to know what would set him off—one night it was being served leftovers for dinner; another night it was the neighbor’s dogs barking, or his discovery that the garbage cans were still out on the curb a few hours after trash pickup was over. When her father’s anger began to build, Pauline’s mother advised her to lie low, to take herself out of the tornado path of his rage. Just as meteorologists learn to read cloud patterns, air pressure, and wind speed for signs that a storm is brewing, Pauline learned to read her father’s face for the earliest hint of anger. If his eyebrows drew together, or if his lips narrowed, Pauline turned and quietly fled to her room. I wondered if what had started out as a smart protective strategy—the ability to tune in to the physical minutiae of her father’s expressions—had grown over the years into a hyperawareness of everyone’s expressions, and the generalization that all of us were just a second or two away from exploding into anger at her.

I smiled at Pauline, and then asked her if she could see that I was smiling at her, and that I was happy that she was here, sharing her concerns with me. Pauline looked up and into my face. After about fifty minutes of talking about five feet away from me, I think this was the first time she felt comfortable enough to see me. She smiled back.

“I’m sorry,” she said. (Apologizing again!) “I don’t think I know how to do this right. The therapists I’ve seen before have always been so critical.”

Certainly, I know a number of psychiatrists who would fit that bill. But I also suspected that Pauline had not been able to see her therapists and read any kindness on their faces. I mean “see” both in the metaphorical sense of understanding another person and in the literal sense of being able to look into another person’s face. I paused two times before our session ended and playfully asked Pauline to look me in the eye for just a moment—which she did, followed by a deep red blush of shame. When I paused and asked her to look at me a third time, she giggled. This was a good sign and an important first step. This was not simply a woman with anxiety. This was a woman with a deep sense of relational fear programmed into her nervous system. Every uncomfortable interaction only made the fear stronger. Unfortunately for Pauline, every interaction was uncomfortable.

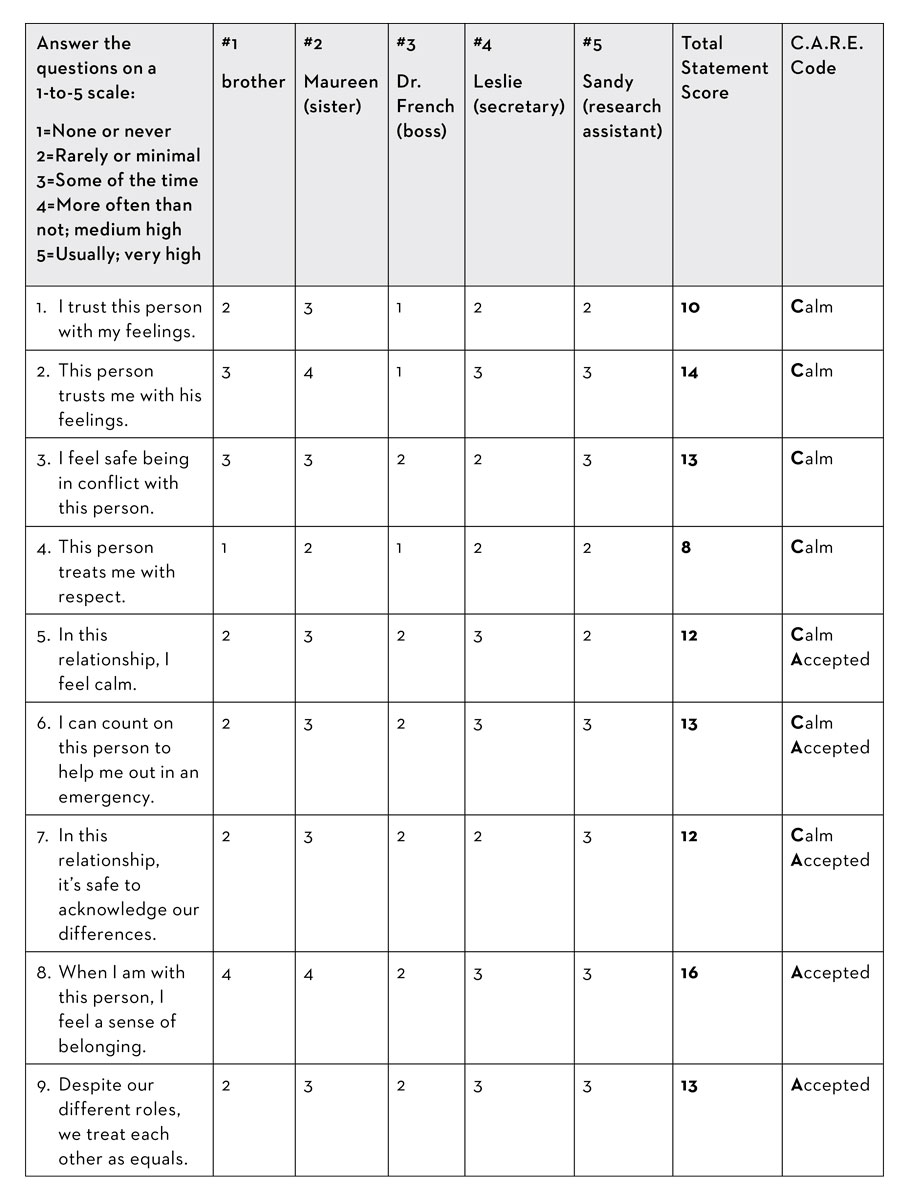

Let’s take a look at Pauline’s C.A.R.E. scores:

Calm (add up scores for statements 1 through 7; maximum total score is 175): 82 (low)

Accepted (add up scores for statements 5 through 11; maximum total score is 175): 94 (low)

Resonant (statements 12 through 16; maximum total score is 125): 71 (moderate)

Energetic (statements 17 through 20; maximum total score is 100): 54 (low)

Pauline’s C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart

Two things immediately struck me about Pauline’s relational assessment. First, only one of her relationships felt even moderately safe. This was her relationship with her outspoken and ambitious sister, Maureen. Pauline wasn’t 100 percent comfortable in Maureen’s company, but she did sense that her sister felt protective of her, and she mostly liked that feeling.

Not surprisingly, Pauline had been drawn to a quiet life, one without a partner or even any close, intimate friendships. She felt so uneasy in any interpersonal interaction that sustained relationships simply stressed her out. Pauline had chosen a career in science that suited her desire for quiet, focused attention, and for years, she’d worked as a research assistant in a lab. She loved plating bacteria on an agar plate and returning the next day to see what had blossomed. There was no reading between the lines; either the bacteria grew or they didn’t. She found this work refreshingly clear, and she was devoted to it—she was usually the person who volunteered to stay at the lab after hours to complete a timed experiment or to finish cleaning up from a long day of work. So it was in the lab where most of her relational time was spent.

Her steadiest work relationship was with Sandy, another research assistant who seemed appreciative of Pauline’s work ethic. Pauline also had regular contact with an older secretary, Leslie, who worked in the lab across the hall, but Pauline found her penchant for doling out grandmotherly advice “too much.” It felt like criticism. There was also her boss, Dr. French. Dr. French was pleasant enough, but Pauline had felt that someone with power must be dealt with cautiously. She paid very close attention to Dr. French and could anticipate things that she wanted or needed. Occasionally, Pauline would curiously watch how Dr. French and Sandy interacted. They were casual together; they even talked about their weekends.

The only other person Pauline spent time with was her brother, who could be a difficult guy. He was opinionated and bossy, and though Pauline felt loyal to her family, she also hated the feeling that he was always annoyed at something she’d done—even when she knew she’d done nothing.

The second thing I noticed about Pauline’s relational assessment was that all her C.A.R.E. pathways were on the low side. In fact, her Resonant score was actually higher than her others. This was a measure of just how anxious, left out, and drained she felt. But it also reflected a few other things. First, Pauline’s ability to read people wasn’t completely off; it was mixed. She could study someone like her boss and learn how to please her. But she also saw anger even when anger wasn’t there. In fact, her highest Resonant scores came from statements about being able to read other people. Pauline wasn’t aware that she was misreading them.

In order to unwind the relational knot Pauline was in, she needed to follow all the steps of the C.A.R.E. program in order. When the Calm and Accepted pathways are weak, people naturally become so preoccupied with their own internal fear systems, and by the relational alarm bells that are constantly sounding, that they are too distracted to see others accurately. After she felt calmer and more trusting (I thought compassion meditation would be particularly good for her—see here), we’d tackle the Resonant pathway. With luck, these steps would improve at least a few of her relationships and spark some good relational energy.

Not everyone with a weak Resonant pathway is convinced that land mines are buried inside every person she meets. Take my friend Dan, who’s got a short fuse. When someone is distant or distracted, he believes that they are intentionally trying to hurt him, so he jumps all over them. Or take Darcy, who imagined—with pleasure and pride—that her employees and family lived in awe of her. She had a rude shove out of that illusion when she was passed over for a promotion and her husband threatened to leave her, saying that she had no idea what he thought or felt.

Ways to Tune up Your Emotional Resonance

What about you? Do you find it hard to know what other people are thinking? Are you often convinced that other people at work hate your proposals, only to find out later that they’ve endorsed your ideas? Do you often feel blindsided by other people’s anger, which seems to come at you out of nowhere? Or have you noticed a subtler pattern of relational drift, of the warmth draining out of relationships that were once cozy and close?

Remember, if you have difficulty reading other people, it’s not because there is something inherently wrong with you. It’s a result of how your brain has been shaped in relationship with others. For example, if you live with a person like Darcy—the woman who liked to think of her husband as an admiring underling—you will eventually suffer the effects. When other people refuse to see your anger or your sadness, it becomes harder for you to see those emotions in yourself. In the vicious circle that by now should be all too familiar, you will then struggle to read anger or sadness in others.

Although your brain is inevitably affected by relationships, you’re not powerless. You can take your neural pathways and reshape them. The exercises below suggest that you begin by spending more time with people who are sensitive to your feelings, and that you reduce the proportion of time you spend with people who can’t see who you are.

From there, learn to label your own emotional landscape and then practice by trying to read the emotions of fictional characters you see on TV or in the movies. Other “safe distance” suggestions include limiting your exposure to violent images, which can overwhelm and confuse your mirroring system, and using the rules of brain change to starve the pathways that devalue particular emotions. When you’re ready, there are several one-on-one exercises you can try within the context of relationships that already feel comfortable.

Spend More Time in Resonant Relationships

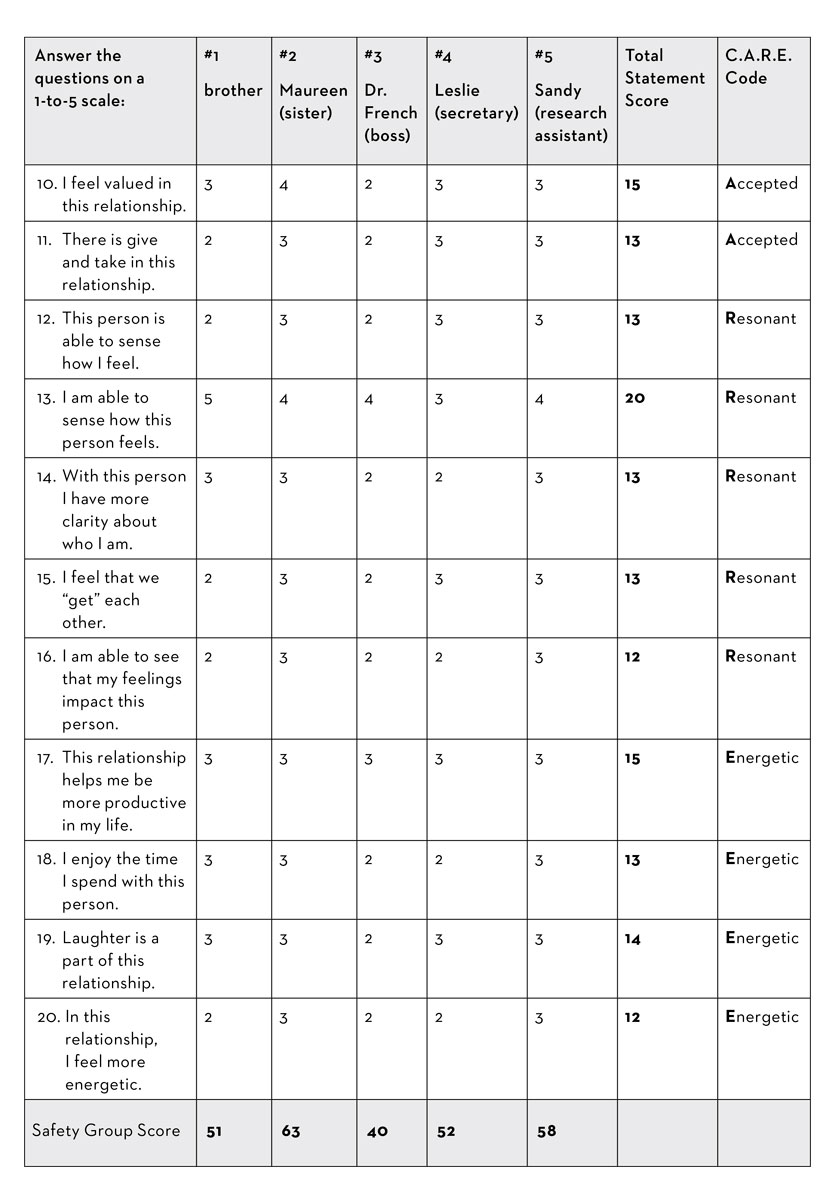

A while ago, I introduced the idea of relative relational time—that we have a certain amount of time we spend in contact with other people, and that it’s useful to know which relationships occupy the highest percentage of that time.

Pauline’s relational time was spent like this:

|

Person |

Percentage of Relational Time |

|

Brother |

25 |

|

Maureen (sister) |

20 |

|

Dr. French (boss) |

20 |

|

Leslie (secretary) |

20 |

|

Sandy (research assistant) |

15 |

If Pauline could spend more time with her sister, who felt fairly safe, and less time with her brother, who felt scary, she would leverage the power of good relationships to help her grow. We agreed that Sandy was another promising friendship, and that maybe she could try spending just a touch more time with her. Pauline started simply, by agreeing to make more eye contact when she and Sandy were talking. Locking eyes and holding the contact was too much, but Pauline could briefly look into Sandy’s eyes and then look away again. She also used her observational habits to notice the kind of coffee Sandy liked and left a cup on her desk with a short, friendly note. Even Pauline could see that Sandy was touched, not angered, by this gesture.

If you are in a relationship with someone who can’t or won’t see you, reduce the damage to your mirroring system by rethinking how much time you spend with this person. Darcy’s husband, for example, wasn’t sure he was strong enough to stand up to his wife until he consciously reapportioned his relational time. He started playing tennis with a friend a few nights a week, and he began taking their children for frequent weekend trips to his parents’ house. This was not done in the spirit of running from his difficulties. Instead, it helped him spend time with people who “got” his emotions, quirks, and personality tics. Eventually, he could remember what anger feels and looks like—and he realized that he was angry enough to have a healthy confrontation with Darcy about their problems.

Sometimes there’s another solution: you can take small steps to improve a relationship that lacks resonance. I once worked with a recently retired woman who had become depressed and numb. Why? This woman had been an office manager, the bright hub of a busy medical practice. Everyone looked to her—literally—for guidance. Her mirroring system received constant positive stimulation. When she retired, it was as if someone had pulled the plug on this part of her nervous system. Her husband, who’d retired a few months earlier, had happily begun several painting projects. He was so absorbed in his new work that he didn’t even look up when she entered the room. At night, he was tired and remote. My client began to ask her husband to say hello to her in the morning, to insist on conversational niceties that he thought were no longer necessary after so many years. After an awkward period in which their “Hello, how are you doing?” phrases sounded artificial, some of the neural pathways for their older, more affectionate habits reawakened. The person she spent most of her time with was now a person who could stimulate her mirroring system, not weaken it.

Identify the Physical Life of Emotions

Researchers have identified six basic human emotions that exist across all cultures:

Happiness

Sadness

Anger

Fear

Disgust

Surprise

These emotions don’t just live in our heads. They have a life in our bodies, too, and even when an emotion is too distasteful to think about consciously, the body expresses it. Anger often lives as a pounding heart and rising blood pressure; fear can surface as chilly hands and feet. People who attend to these body signals and learn to interpret their meaning are better able to read emotions in themselves and in others.

You can cultivate your awareness of emotions in your body. It’s best to do this in a safe and quiet place. Choose the emotion that you’re most comfortable with, and then, with your eyes gently closed, let your mind drift to a time you experienced this feeling.

When I practice this exercise, I can easily generate a list of happy images involving my children. My son and daughter seem to live deep within my bones! One image that particularly captures a sense of happiness for me occurred when I coached my daughter’s softball team. We made it to the championship, and my daughter pitched half the game. She struck out the last girl and the game was won. In the midst of a wild celebration with her teammates, we made eye contact. It was sheer pleasure. When I focus on this image with my eyes closed, I first notice that my chest feels full and that there is a direct connection between the full feeling in my chest and a smile that has formed on my face. I can’t help myself: the feeling of joy travels throughout my body. My hands tingle a bit and I can feel my whole body energized by the memory.

Try on a couple of memories that call up the emotion you’re thinking of. See if the feeling is experienced in the same location and in the same way—and if not, notice the differences. This simple exercise is one you can practice over and over again. The more you do it, the more easily identifiable your feelings will be to you.

Once you’ve practiced with an easy emotion, try a different one, something that feels less comfortable. For many of us, that emotion is anger. For some, it’s fear. A sign that you’re uncomfortable with an emotion is that you often read it in others. If people often seem angry with you or afraid of you, or if they seem so happy it strikes you as ridiculous … bingo. You have a valuable clue.

Jennifer, the young woman whose family gave her the silent treatment, had learned over the years to squish her anger far, far, out of reach. So I asked her to let her mind drift to a time when she could remember feeling mad, really mad. And it was a time she was angry on behalf of someone else—when she first heard about the sexual abuse of young boys at Penn State. She was driving in her car, listening to a sports radio channel, when the news broke in. “The anger exploded in my body like a volcano,” she said. “There was a bandlike feeling around the top of my head. My throat was so full that I wanted to scream.”

When you try this exercise, you might notice that sometimes feelings are more complex and overlapping. When Jennifer lingered on the anger she felt, she noticed a deep heaviness low in her chest, close to her abdomen. It was a profound sense of sadness for the children. Jennifer didn’t enjoy reliving this moment. But it was helpful for her to locate the feeling in her body and to know how to describe it. That way, she’ll be less likely to be angry, or angry/sad, without even realizing it.

As you work on this particular kind of emotional intelligence, be patient with yourself. It took Rufus, who was addicted to Internet porn, about six months before he could identify the basic emotions in his body—and to notice that when something made him angry or hurt, he immediately zoned out so that he was no longer connected to anyone around him. As he got pretty good at noticing feelings in himself, I invited him to notice what I might be feeling. This was difficult for Rufus: first he had to actually look at me and then he had to notice my body language and facial expressions. We passed a milestone one week when I came to work slightly distracted by something happening at my daughter’s school. Without being prompted, Rufus asked if I was angry with him. Instead of jumping to that therapy kickback, “Why do you think I’m angry with you?” I paused and said that I was more distant but that I was definitely not mad at him—just a little concerned about something at home. I appreciated that he pointed this out. It allowed me to refocus on the work he and I were doing together. In fact, we had a great session and I was so absorbed that I was able to put my troubles on the back burner.

Name the Emotional Spectrum

There are six basic emotions, but each of those six has almost infinite grades of intensity. Here are just a few of the words available to describe those grades, ranging from mildest to strongest:

Happiness

Contentment, gladness, happiness, serenity, joy, elation, bliss, euphoria

Sadness

Disappointment, hurt, melancholy, sadness, gloom, despair

Anger

Annoyance, irritation, frustration, anger, rage, fury

Fear

Worry, nervousness, anxiety, helplessness, fear, alarm, panic, terror

Disgust

Contempt, disgust, revulsion, loathing

Surprise

Surprise, shock, amazement, astonishment

People who live in an environment that dismisses the importance of emotions may have an intellectual grasp of each of these words, but it is hard for them to distinguish among these complex states in their own minds and bodies. Annoyance, irritation, frustration, anger, rage, and fury may all blur into one unnamable emotion. Overwhelmed, the person may express the feeling in an impulsive, out-of-control way—or stifle it.

Trying to interact with others when you don’t have the full repertoire of feelings at your fingertips is like trying to run a retail store with nothing but one-hundred-dollar bills. With no variability in the denominations, everything you sell must cost the same regardless of its actual value. A pair of boots and a candy bar would both cost one hundred dollars. The boots may actually be worth that amount, but spending one hundred dollars on a candy bar is never a good idea! (And you’re talking to a candy lover here.) If you have a narrow range of feelings, you may express an intense fury in an interaction when irritation would be more relationally useful. Juan, the computer programmer who raged at his coworkers when they commented on his ideas, comes to mind.

To sharpen your emotional vocabulary, try this exercise, which you can do in private. Identify one of your safest relationships, and then choose one of the six basic emotions and sit quietly while you imagine feeling the mildest version of that emotion toward the other person. Move up the scale of intensity. As you do, notice where you feel the variations of emotion in your body and how those physical feelings change. If you can’t notice a difference yet, that’s fine. As you pay more attention to where feelings arise in your body, and start to think about the words you use to label them, this important relational skill will come more naturally.

Next, recall what happened when you felt each of the emotional shades. Could you express them accurately? If you did, what happened next? In healthy relationships, the expression of emotions usually deepens the relationship—even if the emotion is anger with the other person. Jean Baker Miller said that one of the defining aspects of a growth-fostering relationship is that it produces a clearer sense of yourself, of others, and of the relationship. When your emotions are respected within the relationship, your capacity to form and express your experience grows stronger. So does your ability to hear the other person’s experience.

You might try the same exercise and imagine feeling emotional shades within a riskier relationship. What are the differences? For bonus points, track a character’s emotions in all their grades of intensity as you watch a movie or show.

As you repeat this exercise with other emotions, you connect your cognitive understanding of a feeling with a more differentiated sense of it in your body. Eventually, this will translate into clearer communication in your relationships.

Of course, the ultimate goal is to move this exercise into the real world. When you’re with one of your safest friends, try saying something like, “You seem irritated/joyful/worried today. Does that sound right?” Naming the emotion and then checking in are essential. So many problems come from our failure to confirm that we’re reading people accurately. Then we travel full-speed in the wrong direction, piling up misunderstanding after misunderstanding until the relationship crashes.

All relationships have a rhythm of connection and disconnection. It’s impossible to resonate with another person all the time. The point is not to be perfect in your reading of the relationship but to be more aware of how you’re reading them, and to check out what you’re sensing. This is the Use it or lose it rule of brain change working its magic. The more you stimulate the mirroring pathways, the stronger they become, so they can help you safely span the enormous differences we all encounter in daily life.

Starve Neural Pathways That Separate Feelings from Thoughts

Back in 1976, before anyone was thinking about relational pathways in the brain, Jean Baker Miller introduced the concept of feeling-thoughts—the integration of intellectual and emotional experience that’s necessary for participating in healthy relationships. But in a culture that promotes separation as the goal of healthy human development, we’re not taught to respect feelings. We learn that thoughts are the sign of a mature brain and that feelings are somewhat distasteful and immature. Unfortunately, splitting feelings from thoughts puts you at a relational disadvantage. Your experience of a relationship is largely based on how you feel about it. If you deny or misread those feelings, you can end up communicating in a way that is confusing.

For example, in my psychotherapy practice I often ask clients what they are feeling. Instead, they’ll share with me what they are thinking: “I feel like I do not want to be with my husband anymore” or “I feel like I am done with therapy.” The emotion that is paired with the thought is missing. One of the important tasks of therapy is to reunite emotions with thoughts so that the client can make statements that are more accurate. The statements become more understandable, too: “When I am with my husband I feel lonely and hurt; I do not want to be married to him anymore” or “When I am in therapy, I feel annoyed and angry at the focus on my drinking. I think I will stop therapy.”

Improving your emotional literacy is a way to get better at communicating feeling-thoughts. The exercises I’ve already described can help you do that. You may also need to starve the neural pathways that are telling you to associate maturity with thinking and immaturity with emotions. Watch for these messages in your day-to-day life:

· Do you live in a family that says feelings are for children only (and preferably just girls)?

· If you talk about the way something makes you feel, are you teased or ignored?

· Are you in a relationship with a partner who criticizes you when you mention feelings, rather than just “focusing on the facts”?

When you are expressing strong feelings with someone who has difficulty forming feeling-thoughts, he or she may experience an uncomfortable mirroring of your emotions. The other person may even be flooded with emotions that feel unmanageable—and that’s why the person may become rigidly fixed on keeping emotions out of your conversation.

Your resource against these messages of “thought superiority” is our old method of brain change, relabel and refocus (here). When you’re in a family interaction and are criticized for mentioning your emotions, relabel the criticism as “simply a family belief.” Refocus on a time when you brought feelings into a relationship and enjoyed the connection that followed. Or rely on one of your positive relational moments (here); I often refocus on my PRMs of rich conversations I’ve had with my children and when I do, I can almost feel the old pathways melting away.

Practice In-Person Contact

Are you in a relationship that’s based mostly on technological interfaces, not in-person interactions? Person-to-person contact is essential for exercising mirror neurons. Taking in the sensory input from another person’s expressions and actions will directly stimulate the mirroring system. The more interpersonal context you have, the stronger the neural firing along the mirroring system. If we’re Skyping, you can see my face, and maybe you can see my upper arm moving. But you won’t be able to see that I’m reaching for a cup of coffee on my desk. When we’re not interacting in person, your mirroring system doesn’t get as much information and won’t fire as well.

Please don’t give up on texting, Skyping, FaceTime, and the like—technology has become a basic tool for communication and keeping up friendships. But if you don’t practice in-person interactions, communicating via technology will actually become harder. Why? Because when you have well-connected, robust C.A.R.E. pathways, you are able to read a few words from another person or see just his or her face and be reminded, both mentally and physically, of everything you know about that person. You have a context for understanding the limited information you’re getting via the tech interface. But if you don’t have the body experience of the relationship, you have to rely on other body relationships to help you decode the words or sights. It’s like getting a message from your best friend but reading it as if it came from your mother—which leaves lots of room for misunderstanding.

Reduce Your Exposure to Violent Imagery

Violent imagery is ubiquitous—in games, the news, movies, and television shows. What’s damaging about this imagery is that it rarely shows the effects of the violence on the victims. When we have hurt someone, our brains and bodies need to see the impact of that pain on the other person. Seeing the impact of violence and aggression on the victims directly stimulates your mirror neurons, leading to empathy for the person who has been hurt. In fact, standing in another person’s shoes, or imagining what their experience is like, is an essential part of violence prevention and is the core part of most programs that treat male perpetrators of violence. But disembodied violence is unrealistic and does a disservice to us all. Marco Iacoboni says that

taken together, the findings from laboratory studies, correlation studies, and longitudinal studies all support the hypothesis that media violence induces imitative violence. In fact, the statistical “effect size”—a measure of the strength of the relationship between two variables—for media violence and aggression far exceeds the effect size of passive smoking and lung cancer, or calcium intake and bone mass or asbestos exposure and cancer.2

Being exposed to large-scale violence can alter the adult nervous system, but for children the effect is even worse. They are in the critical period of learning and neural shaping, and they absorb excessive violence without adult filters. The combination of the two factors means that violence becomes built into their mental constructs of relationships.

For these reasons, limit your exposure to violent images. Even I admit that some of the most violent films and movies are also some of the most entertaining—but for the sake of your mental and relational health, watch some comedies instead. If you’re a gamer who is drawn to simulations of war or crime, try some games that are a little more playful or that emphasize collaborative activity. If you find it challenging to make this switch, remember that each episode of violence that you see is mirrored in your body and brain as if you are being violent or being victimized. If you reduce or eliminate that exposure, you’ll feel better.

Know Your Relational Templates

Have you ever begun a romantic relationship with someone you thought was completely different from your parents—and felt relieved that, this time, you wouldn’t spend your time together replaying the most frustrating parts of your childhood? Things go blissfully for a week, a month, maybe even a year … until one day, you wake up and poof!—your perfect partner is telling you how to dress and wear your hair. Last week she taught you the correct way to load the dishwasher, and finally, this morning, as you were hurrying to work, she made a suggestion about how to roll the toothpaste tube. You lost it. You had a full-blown, eight-year-old tantrum, the kind you used to have whenever your controlling mother bossed you around. In that moment, standing at the bathroom sink, it finally happened: your sweet partner, chosen for her laid-back demeanor, had become your critical parent.

There is nothing more disheartening than traveling on these old relational loops over and over. But playing those loops is what almost always happens—because of the way we all learn to read each other’s behavior. If you want to stop repeating old relational patterns, and if you’re ready for some advanced work in reading other people, you need to become familiar with what are called relational templates.

At the place where your mirror system passes through your insula, there is a lifetime’s worth of relational images, which are also known in relational-cultural therapy as relational templates. These are the ideas about relationships that you’ve held for so long you don’t even recognize them. Relational templates are the molds for your ideas about how relationships are supposed to work, what you’re entitled to within a relationship, and what particular actions and expressions signify. When two people misinterpret each other, it’s often because their relational templates are drastically different.

Because early relationships and experiences sculpt our brains, and because our nervous system is drawn to the familiar for safety (even when it isn’t safe!), we all repeat relational templates constantly. These templates become the unconscious rules that dictate how you act in relationships and how you expect others to behave. If much of your experience as a child was positive, with rich, respectful, and responsive people around you, people who were able to listen to others and to speak their voice, who could negotiate and compromise, you are probably in pretty good shape relationally. The skills of healthy relating will be built into your brain and body: you are more likely to have a calm dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, a robust smart vagus nerve to help modulate stress, and plenty of dopamine from family and friends. And you are much more likely to have a well-oiled mirror neuron system, with the ability to see people clearly.

In a culture that values separation, however, it is common to form a relational template that undermines your ability to read others and to be in a healthy relationship. An example is the close friendship between my friends Rob and Mary. They met in college, and as they realized they shared similar interests, values, and life goals, they became inseparable. Everyone thought they should get married, but Rob and Mary agreed that having the other for a spouse would be like marrying a sibling. The friendship survived graduation, cross-country moves, first jobs, and Mary’s marriage. Even though they were on opposite coasts, they talked weekly and texted or e-mailed daily. Until Mary had a child. Rob flew east for the christening, and it was during that visit that a long-standing impasse began.

In Rob’s mind, Mary was over-the-top obsessed with her child. She couldn’t talk about anything else. You can put her down for just one minute! Rob would think as Mary tried to carry on conversations with Rob about her baby—all the while tending to her baby. Rob knew that babies are adorable and that they require hard work, but wasn’t this a little much? He was surprised to feel divorced from Mary’s world. Am I really jealous of a baby? he wondered.

Mary picked up on Rob’s distraction, but she assumed he was just consumed by a job he’d recently started. But over the months, Rob grew frustrated by how long it took Mary to respond to his messages and how often she had to end their phone calls because of some need of the baby’s. And talk about the baby was a colossal bore to Rob. He grew more and more distant. Their communication faded. Both felt an enormous loss but had no idea what to do about it.

Neither realized that deep-seated relational templates were playing out in the way they related to each other. Mary had grown up as an only child and had loved every minute of it. Her mother had doted on her and still did. Every month or so, she’d send Mary a care package filled with all her favorite treats—this made Mary feel seven years old again, in the best way possible—and they enjoyed long, chatty conversations. Mary always expected that she’d be the same kind of mother to her own child. Who wouldn’t make a baby the center of the family universe?

Rob also enjoyed attentive parents—until his brother was born with cerebral palsy. Rob’s mother and brother nearly died during the birth, and although both survived, little Jonathan was disabled for life. The house was transformed into a medical ward filled with wheelchairs, special beds, oxygen, and medications to keep Jonathan alive. Everything about their lives needed to fit around his schedule. Rob knew that his parents still loved him, but they were so overwhelmed and tired from taking care of his brother that he couldn’t help feeling left out.

In print, it’s not hard to see how Rob’s and Mary’s experiences have formed two very different relational templates. But the nature of relational templates is that they’re our only reference point for how relationships should work. They feel like an instinctive list of the things all people are just supposed to know about how we relate with others. So to Mary, it felt like “everyone knows” that a new baby is supposed to be the center of everyone’s attention. To Rob, it seemed that “everyone knows” that when you stop paying close attention to your best friend, you’re sending a clear message to that friend: bye-bye. Rob and Mary didn’t realize that they were reading from two different scripts, so they were both confused and hurt.

The tension broke one evening when Mary reached out to Rob in tears. Despite their distance, he was the only person she wanted to talk to about how isolating and tiring it can be to take care of a child full time. Rob was so relieved that Mary still saw him as a confidant that he was able to step out of his anger and feel compassion. They had a long talk that night, each explaining what they’d been thinking and feeling. Rob was finally able to make sense of his anger as he described the pain of being pushed out of his mother’s arms by a sick little brother. Mary realized that not everyone shared her mother/baby ideal. By identifying elements of their relational templates, they were able to see each other more clearly and compassionately. This is how a good relationship can shape your brain for the better. In this case, Rob’s and Mary’s mirror neuron systems were strengthened when they learned more about how to “read” each other.

Relational templates are a major reason we misread people. Rob’s relational template told him that a mother can love only one person at a time. Pauline’s template told her that everyone teeters on a knife’s-edge of anger. Jennifer’s template framed low expectations of how other people would act toward her; she hardly knew when she was being mistreated. If you build an awareness of these deeply grooved mental pathways, you can more easily find your way to clarity when things in the relationship become confusing or fuzzy. It’s like knowing to put on your prescription glasses to correct your out-of-focus vision. And we all need these “glasses” to help us see others, because we’ve all internalized different relational templates.

Use Your C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment to Spot Patterns

One way to spot some of your relational templates is to review the results of your C.A.R.E. Relational Assessment Chart. Look for patterns that carry over from one relationship to another. For example, Jennifer noticed that she had only one relationship in which she felt clear about herself most of the time. Eventually she decided that when she entered into most relationships she would feel confused—not just about how to express her needs but what those needs actually were. She hadn’t quite felt the pain of this confusion before, because her family life had taught her it was normal to not be seen, heard, or understood. One client, who’d just realized that she played the emotional caretaker for her group of friends, arched her eyebrows and said, “Well, that sounds familiar. And by familiar, I mean familial.” Of course, relationships are not simply replays of past relational experiences; each has its own tempo and color. So each relationship you evaluate will look a little different from the others. Nevertheless, you’ll probably spy some general patterns.

Let Friends Help You “See” Your Template

Minds can get caught in perpetual self-deceptive loops. (“It’s not that I imagine that other people are angry,” Pauline said to me, “it’s just that nobody else but me can see how angry they are.”) That’s why you’ll want to collect some information about your relational patterns that comes from outside yourself. Invite someone from your relational safety group to give you honest feedback about how he or she sees you in your relational world. (If you don’t have anyone in that group yet, wait until you do. If you ask someone who doesn’t see you clearly to perform this work, you could end up with a distorted view of yourself.) Most people are hesitant to offer criticism of their friends, so here’s a list of questions to get the conversation started:

1. Am I always the one doing the caretaking?

2. When other people have strong opinions, do I defer to them?

3. Do I have a hard time listening to others?

4. Do I get angry when other people challenge me?

5. When there is a conflict, do I get hurt easily and withdraw?

6. Am I aggressive when I don’t get my way?

7. Do I act differently with men than with women?

8. Am I controlling?

9. Am I often too scattered and distracted to engage with people?

10.Do I say things impulsively that hurt people’s feelings?

Unlock Implicit Memories

Explicit memories are the visual, often narrative memories that you can picture in your mind. You can’t start saving explicit memories until the hippocampus, the memory storage in your brain, forms sometime between the ages of three and six. When people ask you about your very first memory, they’re really asking about your first explicit memory. Your implicit memory, on the other hand, is formed in your first couple years of life, before the hippocampus is up and running. Memories that are stored implicitly are thought to be related to the action of the amygdala, which is associated with emotions and stress; these memories come up not on visual tracks but as feelings and bodily sensations.

You may not be able to “remember,” in the traditional sense, the times your mother pushed you away when you were scared, or the times in nursery school when other children made fun of your lisp, or even the moments of absolute peace and comfort when you nestled into your grandmother’s soft lap. Implicit memories are not visual; they’re more like subliminal background noise stored in the cells of your body, constantly feeding you information about what to expect in the world. They may emerge as feelings or bodily sensations, as when you find yourself flooded with a strong dislike for someone with no apparent cause, or when a stranger seems familiar to you. Because these implicit memories don’t feel like memories, they become the “truths” we fail to question, our biases, and source of any rigidity we feel in relationships. They also feel like the essence of your nature, so changing them or even identifying them as having the potential for change can feel downright scary.

I can’t give you a way to track your implicit memories to an external event in the world. But there’s a way to track some of the “truths” that are triggered by powerful implicit memories, and to help you realize how relative these truths can be. Begin by recalling a time when you were in a seemingly unresolvable conflict with someone. What was the truth you carried into the conflict—the idea that you knew, deep down, was correct and just? When you can identify this truth, you can be pretty sure you’re touching the tip of an implicit memory.

Now try to identify the truth you believe the other person brought into the conflict. And then—here’s the hard part—imagine a bridging truth that would allow both realities to exist. For example, Rob and Mary were each eventually able to identify the truths they brought into their conflict about how people should treat each other. A bridging truth was that a mother’s tight bond with her baby could be healthy, but that the time she devoted to creating that bond could cause the mother’s friend to feel lonely. Another bridging truth was that Rob and Mary missed each other and wanted the relationship to continue.

The point of this exercise is not to change all your core beliefs but to bring you an awareness of how relative and experiential they are. Sane people can and will differ on some pretty critical life issues, and having the brain flexibility to imagine the outlines of another person’s relational template is a key relational skill.

Starve Unwanted Relational Images

So far, I’ve described how to reduce the power of your relational template by becoming more aware of it. In this final step, you can use the rules of brain change to actually change some of the relational images within your template. Make a mental list of the relational ideas that form your individual template; note how you feel when a relationship bumps up against one of those ideas. Decide which memories, images, and ideas you want to hold on to and which ones you’d like to move further into the background. You can’t delete your memories, but you can move them further into the background of your mind. They will still be part of your life, but they can be a part that has little relevance to your relationships today.

And it’s back to the relabel and refocus technique to starve the unwanted relational images. When an unwanted implicit or explicit memory makes itself known, simply label it as an old relational image. By giving it a name, you’re separating the image from absolute reality. Then call on the third rule of brain change: Repetition, repetition, dopamine. Every time you relabel the image, refocus your mind on an especially pleasant PRM. With time (that’s the repetition part), the old relational images will fade. (For more about relabeling, refocusing, and PRMs, see here.)

Rob, who realized how close he’d come to drifting away from his friend Mary forever, tried this technique. His template had been formed by the feeling that people he loved would push him aside, that he’d get bumped out by someone who was needier and more important. His head told him that his little brother was sick and vulnerable—of course he needed most of his parents’ attention—but the memories stored in his body told a different story. When he imagined that time period, he could feel his heart beating faster, his chest growing tight, and his whole body coursing with a feeling of irritability. He could also feel, just below the anxiety, a profound sadness. When he paid attention to this feeling, forgotten images emerged: before his brother was born, he’d been excited. He was going to be a big brother! He was going to show this little guy his favorite toys; they were going to share a bedroom; and when they were supposed to go to sleep they would stay awake and have fun together. The grief of that loss was profound.

This loss—which was a controlling relational image for Rob—had influenced his adult interactions. Whenever he would become interested in a woman, he would immediately say to himself, Don’t get your hopes up. He didn’t like to let himself look forward to anything; he tried not to put himself in a position where he could be disappointed. In fact, that’s why his relationship with Mary worked so well. She was a friend, with no pressure for anything more to develop. He loved that. It felt safe. But this impulse toward safety above all else had almost ruined his friendship with Mary, and it had ended other relationships before they could get off the ground.

Slowly, Rob began to starve the neural pathway, the one that told him not to get his hopes up. When he met a new person at work or a woman he liked, warnings poured into his head—and Rob reminded himself, “These are the ghosts of old memories from when my brother was born; they do not apply today.” Then he focused on how he and Mary had reconnected. As his relational images became more explicit to him, they released their grip; and as he devoted more neural space to the memory of diving deeper into his friendship with Mary, he grew more confident. There is nothing more powerful than realizing you’ve rewired your brain for more hope and happiness.