The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition (2016)

Z

Zaamiel: (![]() ). “Rebuke of God.” The angel of whirlwinds (III Enoch).

). “Rebuke of God.” The angel of whirlwinds (III Enoch).

Zaapiel: (![]() ). “Wrath of God.” A destructive angel in charge of the utterly wicked souls in Gehenna. He torments them with rods of burning coal that turn their flesh black. He is also identified as the angel of storms (III Enoch; BhM 5:186).

). “Wrath of God.” A destructive angel in charge of the utterly wicked souls in Gehenna. He torments them with rods of burning coal that turn their flesh black. He is also identified as the angel of storms (III Enoch; BhM 5:186).

Zacuto, Abraham: Astrologer (Spanish, ca. 15th-16th century) who served in the court of Manuel I of Portugal from 1494 until the expulsion of Jews from the country in 1497. He is the author of Sefer Yuhasin (“The Book of Descent”), a history of the Sages of Israel, an account that includes many of the miracles associated with them.

Zacuto, Moses: Kabbalist and poet (Italian, ca. 17th century). His interest in ghostly possession and his accounts of performing exorcisms helped popularize these ideas in the Italian Jewish community. He was actually a sophisticated diagnostician and attempted to distinguish between genuine possession and mere mental illness. He is the author of Shoresh ha-Shemot. SEE EXORCISM; POSSESSION, GHOSTLY

Zagzagel: (![]() ). Another name for the angelic Sar ha-Torahs (Gedulat Moshe).

). Another name for the angelic Sar ha-Torahs (Gedulat Moshe).

Zakiel: (![]() ). “Comet of God.” A fallen angel who teaches mankind the art of divining through the study of clouds (I Enoch).

). “Comet of God.” A fallen angel who teaches mankind the art of divining through the study of clouds (I Enoch).

Zambri: A mythical medieval Jewish sorcerer appearing in Christian tradition. He fought (and lost) a magical duel with Pope Sylvester (Jacobus de Voragine).

Zar: A possessing evil spirit or djinn mentioned in Ethiopian Jewish traditions.

Zayin: (![]() ). The seventh letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It has the vocalic value of “z” and the numeric value of seven. It signifies the Sabbath, the World to Come, and the wholeness of reality: the six cardinal points of the physical world (north, south, east, west, up, down) plus the dimension of spirit. The word itself also means “penis.” 1

). The seventh letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It has the vocalic value of “z” and the numeric value of seven. It signifies the Sabbath, the World to Come, and the wholeness of reality: the six cardinal points of the physical world (north, south, east, west, up, down) plus the dimension of spirit. The word itself also means “penis.” 1

1. Munk, The Wisdom of the Hebrew Alphabet, 104-11.

Zebulon: One of several mythical Jewish magicians of extraordinary prowess who feature prominently in Christian medieval legends.

Zechariah: The name of several people in the Hebrew Scriptures, most notably the post-exilic prophet and author of the biblical book that bears his name. The prophet Zechariah was a seer-like figure who experienced numerous vivid, highly encoded apocalyptic-style night visions. It is impossible to say specifically whether these were dreams or waking visions. It is also possible the prophet is experiencing angelic possession during the oracles in which he describes the malach doveir bi, “The angel that spoke with/within me.”

There is a conflated tradition of a righteous figure named Zechariah who was murdered on the Temple grounds by killers unknown (II Chron. 28). In some versions, this was the prophet Zechariah, in others it was a noble pre-exilic person also named Zechariah. Whoever this particular Zechariah was historically, after his murder in the Temple his blood continued to bubble out of the Earth as a reproach to his murderers. After he captured the Temple grounds, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar tried to stop the eruption by spilling the blood of thousands of Jews over the spot, but this blood atonement proved fruitless, since the descendants of the killers were not among the victims (Zech. 1; J. Tan. 69a).

Zechut Avot: (![]() ). “Merits of the Ancestors.” In gauging the moral worth of any generation of the people Israel, God adds the merit of the Patriarchs and Matriarchsto their descendants. The worth of the ancestor makes it easier for God to more readily forgive any failings of the children. Being directly descended from a particular person, such as Joseph, brings even more benefit (Siddur, Avot Prayer; Lam. R. proem; Ber. 20a). This belief arose from the long-standing Jewish confidence in the continuing presence of the dead and their and influence on the living has been, in different forms, a feature of Jewish belief from earliest times.

). “Merits of the Ancestors.” In gauging the moral worth of any generation of the people Israel, God adds the merit of the Patriarchs and Matriarchsto their descendants. The worth of the ancestor makes it easier for God to more readily forgive any failings of the children. Being directly descended from a particular person, such as Joseph, brings even more benefit (Siddur, Avot Prayer; Lam. R. proem; Ber. 20a). This belief arose from the long-standing Jewish confidence in the continuing presence of the dead and their and influence on the living has been, in different forms, a feature of Jewish belief from earliest times.

With the prophetic verse Jeremiah 31:15-16 serving as locus classicus, “A cry is heard in Ramah, wailing, bitter weeping, Rachel weeps for her children, she refuses to be comforted …” the Sages of Talmudic times believed that their ancestors were aware of what transpired on Earth and would plead before God on behalf of their descendants (Tan. 16a; Men. 53; Lam. R. 24). Mirroring the rise in Christian and Muslim saint veneration, zechut avot practices such as praying to them for their intercession during pilgrimages and prayers for divine intervention. The custom of graveside veneration endures and thrives to this day in some sects of Judaism, and is extended, in some cases, even to modern heroes.

Zeira, Rabbi: Talmudic Sage (ca. 4th century). Working with Raba bar Joseph, he created a golem. In another incident mentioned in Talmud, Raba sent a golem to Zeira, who immediately turned the creature back to dust. On another occasion, an ominous dream caused him to make a pilgrimage from Iraq to Israel (Ber. 57a).

Zeira, Rabbi: Talmudic Sage (ca. 2nd century). This Sage was a talented diagnostician of witchcraft. He restored to human form a person who had been shape-changed into an ass (Sanh. 67a).

Zer Anpin: ( ![]() ). In Sefer Zohar, this is the aspect of God’s generativity, God as Creator. It is understood to be the androgynous divine source of life that is mirrored in the human genital forms (Bahir 30:168-74).Later sources, perhaps euphemistically, identify the Zer Anpin as God’s “beard.” It eventually forms one element in the Lurianic concept of the Partzufim. SEE PHALLUS.

). In Sefer Zohar, this is the aspect of God’s generativity, God as Creator. It is understood to be the androgynous divine source of life that is mirrored in the human genital forms (Bahir 30:168-74).Later sources, perhaps euphemistically, identify the Zer Anpin as God’s “beard.” It eventually forms one element in the Lurianic concept of the Partzufim. SEE PHALLUS.

Zera Kodesh: “Seed of Holiness.” A 17th-century handbook that explains the procedures for exorcizing spirits of the dead. SEE DYBBUK; EXORCISM.

Zerubbabel, Sefer: An apocalyptic text of Late Antiquity ascribed to the authorship of the post-Exilic Jewish leader Zerubbabel, which describes the end of the world. Many of the traditions concerning Armilus, an “Antichrist” like figure, appear here, as do tales of Hephzibah, the mother of the Messiah.

Zebul: (![]() ). “Dwelling.” One of the seven heavens(Chag. 12b-13a), it is the plane on which the Heavenly Temple exists and the angelic priests continue their sacrifices in God’s honor. The name is derived from Habakkuk 3:11.

). “Dwelling.” One of the seven heavens(Chag. 12b-13a), it is the plane on which the Heavenly Temple exists and the angelic priests continue their sacrifices in God’s honor. The name is derived from Habakkuk 3:11.

Zion, Mount: (![]() /Har Tzion, also Har ha-Bayit). Also known as Mount Moriah and the Temple Mount, it is historically the eastern hill of Jerusalem situated between the Valley of Hinnom and the Valley Kidron, which is the site of the First and Second Temples. It is the point where God first created light and began the creation of the universe (Ps. 50:2; Eccl. R. 1:1) and the Even ha-Shetiyah, the Foundation Stone that holds back the waters of the abyss, first emerged from primordial chaos. It is the center of the universe (Tanchuma, Kedoshim 10). Adam was created from the dust of the mountain, from the spot where the altar would eventually rest (Mid. Konen 2:27). Noah made his offerings to God there after the Flood. When the Children of Israel needed to cross the Reed Sea to escape Pharaoh, God transported Mount Moriah to the bottom of the sea, and the Israelites walked across on it (MdRI BeShallach).

/Har Tzion, also Har ha-Bayit). Also known as Mount Moriah and the Temple Mount, it is historically the eastern hill of Jerusalem situated between the Valley of Hinnom and the Valley Kidron, which is the site of the First and Second Temples. It is the point where God first created light and began the creation of the universe (Ps. 50:2; Eccl. R. 1:1) and the Even ha-Shetiyah, the Foundation Stone that holds back the waters of the abyss, first emerged from primordial chaos. It is the center of the universe (Tanchuma, Kedoshim 10). Adam was created from the dust of the mountain, from the spot where the altar would eventually rest (Mid. Konen 2:27). Noah made his offerings to God there after the Flood. When the Children of Israel needed to cross the Reed Sea to escape Pharaoh, God transported Mount Moriah to the bottom of the sea, and the Israelites walked across on it (MdRI BeShallach).

The mount is a place of revelation. According to Pirke de-Rabbi Eliezer, it was miraculously formed from several hills to be the place where the Akedah, the trial of Isaac would take place (15). There Abraham almost sacrificed his son Isaac, when an angel appeared, telling him not to kill his son (Gen. 22). Jacob also had his dream/vision of angels while sleeping on the mount (Gen. 28:11).

In recent centuries, the term “Mount Zion” has been transferred from the eastern ridge above the biblical City of David to a spur of the western ridge of Jerusalem, across from the original Mount Zion. This is a modern misnomer.

Zipporah: The Midianite wife of Moses. When her father Jethro first encountered Moses, he threw Moses into a pit. She kept him alive ten years by secretly feeding him until her father relented (Sefer Zichronot 46:9). She protected her husband from supernatural attack by circumcising their son Gershom and then throwing the detached foreskin in front of Moses while reciting verses of power. Some sources regard the assailant to be Satan, others, destructive angels (Ex. 4; Ned. 32a; Ex. R. 5:8). SEE CIRCUMCISION; SATAN; SERPENT.; WOMEN.

Ziviel: “Affliction of God.” An angel mentioned in the Book of the Great Name.

Zivvuga Kaddisha: (![]() ). “Holy Union.” The concept of a hieros gamos, of divine union, between the masculine and feminine aspects of God (Zohar I:207b; Zohar III:7a). This is a major theme in Zoharic Kabbalah . Isaac Luria taught that there are five types of Zivvuga that occur within different levels of the Godhead (Sefer ha-Hezyonot 212-17). He believed that humans engaging in sex at different times, with different intentions (such as procreation versus companionship) mirrored and influenced these higher unions.1 SEE SEFIROT; SEX; SHEKHINAH.

). “Holy Union.” The concept of a hieros gamos, of divine union, between the masculine and feminine aspects of God (Zohar I:207b; Zohar III:7a). This is a major theme in Zoharic Kabbalah . Isaac Luria taught that there are five types of Zivvuga that occur within different levels of the Godhead (Sefer ha-Hezyonot 212-17). He believed that humans engaging in sex at different times, with different intentions (such as procreation versus companionship) mirrored and influenced these higher unions.1 SEE SEFIROT; SEX; SHEKHINAH.

1. Fine, Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos, 196-205.

Ziz: (![]() ). A giant mythological bird, sometimes called the Queen of Birds (Ps. 50:11). It may be the Hebrew version of Anzu, the mythological primeval bird of Mesopotamian myth. It’s biblical roots are found in psalms 50 and 80:14. In Psalm 50 it parallels Behemoth, suggesting both are the sovereigns of their animal type. It is cosmic in its dimensions:

). A giant mythological bird, sometimes called the Queen of Birds (Ps. 50:11). It may be the Hebrew version of Anzu, the mythological primeval bird of Mesopotamian myth. It’s biblical roots are found in psalms 50 and 80:14. In Psalm 50 it parallels Behemoth, suggesting both are the sovereigns of their animal type. It is cosmic in its dimensions:

Rabbah b. Bar Hanna further related: Once we traveled on board a ship and we saw a bird standing up to its ankles in water while its head reached the sky. We thought the water was not deep and wished to go down and cool ourselves, but a Bat Kol called out: “Do not go down there, for a carpenter’s axe was dropped [in the water] seven years ago and it has not [yet] reached the bottom.” R. Ashi said: That [bird] was Ziz Sadeh “for it is written: And Ziz Sadeh is with me.” (B.B. 73b)

Its wings when spread eclipse the sun (Gen. R. 19:4; Lev. R. 22.10; Mid. Teh. 18.23). It can stand in the sea and the water only covers its ankles, while its head reaches heaven. When Ziz rides on the back of Leviathan, the bird can see the Throne of Glory and sing to God. The beating of its wings can change the direction of the winds. Like Leviathan and Behemoth, Ziz is destined to be served at the messianic banquet (B.B. 73a-74a). SEE ANIMALS.

Zodiac: (![]() ). The system of dividing the night sky into zones for the purpose of astrological reading and interpretation. Zodiacs are quite ancient and may be alluded to in the Bible as early as the 7th century BCE, where a reference to mazzalot (stars, or perhaps, constellations) is understood by some scholars as a term for a zodiac (2 Kings 23:5). Others speculate an earlier reference to the zodiac appears as graffiti on a tomb site at Khibet el Qom in Israel (8th century BCE). Based on their order the four initials written there, alef, bet, mem, and alef, suggest they may be referring to four signs of the zodiac.

). The system of dividing the night sky into zones for the purpose of astrological reading and interpretation. Zodiacs are quite ancient and may be alluded to in the Bible as early as the 7th century BCE, where a reference to mazzalot (stars, or perhaps, constellations) is understood by some scholars as a term for a zodiac (2 Kings 23:5). Others speculate an earlier reference to the zodiac appears as graffiti on a tomb site at Khibet el Qom in Israel (8th century BCE). Based on their order the four initials written there, alef, bet, mem, and alef, suggest they may be referring to four signs of the zodiac.

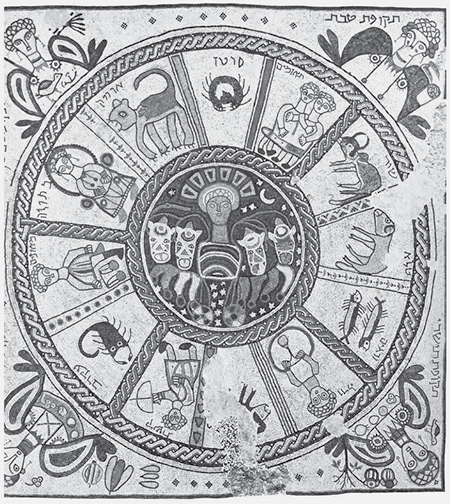

Jewish zodiac systems derived from, or at least influenced by, the Western traditions of astrology are evident by Late Antiquity, when the mystical manual Sefer Yetzirah makes repeated references to Greco-Roman zodiac houses such as the Gedi (Capricorn), the Shor (Taurus), and the Dagim (Pieces) (SY 4:6-5:10, Short Recension). More surprising, a magnificent mosaic zodiac featuring all the familiar houses is the decorative centerpiece of the floor of the 5th-century Beit Alfa synagogue that was unearthed in northern Israel. By this time the names of the twelve zodiac signs (mazzalot) are established: Taleh (Aries), Shor (Taurus), Teomim (Gemini), Sartan (Cancer), Aryeh (Leo), Betulah (Virgo), Moznayim (Libra), Akrav (Scorpio), Keshet (Sagittarius), Gedi (Capricorn), D’li (Aquarius), and Dagim (Pisces) (Yalkut 418).

By the early Middle Ages, the zodiac was an accepted part of Jewish astrology and had been fused with traditional Jewish angelology, with each house having its own principal angel and heavenly host (Ber. 32b). One Midrash uses the zodiac signs as an allegory to chart the progress of a man’s life (Tanh. Ha’azinu 1). For each of the houses of the zodiac, God created thirty hosts of angels; one host for each of the 360 degrees of the heavenly circumference (Ber. 32b).

Sections of Hebrew magical manuals such as Sefer ha-Razim (“The Book of Mysteries”) and Sefer Raziel ha-Malach (“The Book of [the Angel] Raziel”) are devoted to the influence of the zodiac over the universe.

Mainstream figures in medieval Jewry were more divided on the issue of astral influences than the Jewish populous, who generally accepted the power of the stars. The rationalist philosopher Maimonides, for example, utterly dismissed the value of astrology, while others, like the Bible exegete Abraham ibn Ezra, gave it great credence. The physician Abraham Yagel (Italian, ca. 16th century) even used the zodiac in his diagnosis and treatment of his patients. Interest in the supernatural influence of the zodiac has faded among Jews, but has never entirely gone away.

Zodiac mosaic in 6th century Beit Alpha synagogue

Zohar, Sefer ha-: “The Book of Radiance.” This massive masterwork of Spanish Kabbalah is the single most influential work of esotericism in Judaism. Part esoteric commentary, part medieval romance, and part mystical gospel, the Zohar is ostensibly the work of the 2nd-century Galilean Sage Simon bar Yochai. In fact, most of the collection is the work of Moses (shem tov) de Leon of Guadalajara (ca. 13th century), with other sections added by anonymous contributors. Rabbi Moses composed the Zohar, partly through automatic writing, in a series of booklets he sold and distributed over his lifetime. As a result, the Zohar text we have today is actually an anthology of the surviving manuscript booklets brought together at the advent of the printing press.

The core of the published book (18th century) consists of three sections: commentaries on Genesis, Exodus, and the last three books of the Torah. In addition, these are usually published with several related compositions: partial commentaries on Song of Songs, Ruth, and Lamentations, the early Zohar Chadash, the later Ra’aya Meheimna, and the much later Tikkunei Zohar.

Written in an eccentric, poetically charged Aramaic, the Zohar is at turns lyrical, fantastic, and downright cryptic. At times the text revels in paradox, riddles, and obscure and elliptical pronouncements. It is also charged with erotic themes throughout.

The single most outstanding idea in it is its elaborate and complex concept of the sefirot (the Pleroma of divine powers). These ten divine forces, unfolding at different levels, revealing rungs of divine purpose and function, are the centerpiece of the Zohar’s theosophy. The workings of these sefirot are then applied to the Bible, simultaneously revealing the inner workings of the Pleroma and illustrating the divine energies at play in all aspects of the biblical narratives. Every figure and event in the Bible is correlated to the sefirot, highlighting the analogous movement of forces both divine and earthly.

The Zohar also gives a highly mythological view of the cosmos, with the forces of the sefirot also expressed through demons , heavenly beings, and mythic locales. Most startling of all is the frankly sexual interpretation the Zohar applies to the Godhead. God has both masculine and feminine aspects that are engaged in a dynamic divine drama of ongoing hieros gamos in order to achieve perfect unity. The people Israel is a crucial element of the lowest of the sefirot, Malach, and has a central role in sustaining this divine process of unification. Mortals effect this ongoing divine unification through diligent observance of the mitzvot, bringing the right intention to their performance, and by other specific acts of imitato dei.

Another outstanding aspect of Zoharic theosophy is its interpretation of evil. Drawing on the teachings of Treatise on the Left Emanation, the Zohar teaches that evil is really an emanation of the sefirah Gevurah, of divine justice, that becomes sustained and distorted by human wickedness.

The work devotes surprisingly little attention to the personal mystical experience or how to achieve it. The one distinctive mystical pursuit mentioned in the Zohar is devekut, “cleaving,” or erotic-passionate attachment to God.1Mostly this is achieved through the mystical revelations that unfold in sacred study, though other mystical customs—intensive prayer and meditation, self-denial, and ecstasy-inducing practices, like sleep deprivation—also play a role. Most importantly, Zohar consistently sees humanity (specifically Jews) and the lower sefirot on a kind of continuum, blurring the distinction between Israel and its God. This is why Jews both facilitate and participate in the ongoing Tikkun of zivvuga kaddisha, “Holy Union.”

The impact of the Zohar on subsequent Jewish mysticism is unparalleled. Its importance soared in the aftermath of the catastrophic expulsion of Spanish Jewry, as those exiles found meaning for their plight in the complex interplay of the sefirot. In some segments of the Jewish community, the Zohar eventually stood on par with the Bible and Talmud as an authoritative text. It also had a profound impact on Christian Qabbalists of the Renaissance and later, who combed the murky language of the Zohar for secreted references to the Trinity and other Christian doctrines.

1. Matt, The Zohar: Pritzker Edition, vol. 1, lxix-lxxi.

Zohar Chadash: “New Radiance.” Paradoxically, this “new” section of the Zohar is one of the oldest parts of the collection, a section including many esoteric Midrashim.

Zombies: (![]() ). While there is not a large tradition of stories about people reanimating dead bodies (as opposed to fully resurrecting a person), there are a few medieval and early modern European stories of how one may make a zombie by writing the secret Name of God on a parchment and inserting it under the tongue of a corpse or into an incision in the skin. Removing the parchment reverses the effect (Sefer Yuhasin). This description closely parallels traditions on the construction of a golem. In one account, the dead, driven by a need unfulfilled during life, can spontaneously start to walk the Earth again (Shivhei ha-Ari). Virtually all other traditions assume that zombies must be animated by an adept (Ma’aseh Buch 171). SEE RESURRECTION.

). While there is not a large tradition of stories about people reanimating dead bodies (as opposed to fully resurrecting a person), there are a few medieval and early modern European stories of how one may make a zombie by writing the secret Name of God on a parchment and inserting it under the tongue of a corpse or into an incision in the skin. Removing the parchment reverses the effect (Sefer Yuhasin). This description closely parallels traditions on the construction of a golem. In one account, the dead, driven by a need unfulfilled during life, can spontaneously start to walk the Earth again (Shivhei ha-Ari). Virtually all other traditions assume that zombies must be animated by an adept (Ma’aseh Buch 171). SEE RESURRECTION.

ABBREVIATIONS OF CITATIONS

FROM TRADITIONAL TEXTS

|

Abbreviation of Biblical Books |

|||||

|

Genesis |

Ezra |

Joel |

|||

|

Exodus |

Nehemiah |

Amos |

|||

|

Leviticus |

Esther |

Jonah |

|||

|

Numbers |

Job |

Micah |

|||

|

Deuteronomy |

Proverbs |

Nahum |

|||

|

Joshua |

Ecclesiastes |

Habakkuk |

|||

|

Judges |

Song of Songs |

Zephaniah |

|||

|

Ruth |

Isaiah |

Haggai |

|||

|

1 Samuel |

Lamentations |

Zechariah |

|||

|

2 Samuel |

Jeremiah |

Malachi |

|||

|

1 Kings |

Ezekiel |

1 Corinthians |

|||

|

2 Kings |

Daniel |

2 Corinthians |

|||

|

1 Chronicles |

Hosea |

Revelation |

|||

|

2 Chronicles |

Psalms |

||||

|

Abbreviation of Talmud Tractates |

|||||

|

Arakin |

Keriot |

Pesachim |

|||

|

Avot |

Ketubot |

Rosh Hashanah |

|||

|

Avodah Zarah |

Kiddushin |

Sanhedrin |

|||

|

Baba Batra |

Kinnim |

Semahot |

|||

|

Bechorot |

Kutim |

Shabbat |

|||

|

Berachot |

Makkot |

Shekalim |

|||

|

Betzah |

Makhshirin |

Shevuot |

|||

|

Bikkurim |

Meilah |

Sofrim |

|||

|

Baba Kama |

Megillah |

Sotah |

|||

|

Baba Metzia |

Menahot |

Sukkah |

|||

|

Chagigah |

Mezuzah |

Tamid |

|||

|

Challah |

Middot |

Ta’anit |

|||

|

Chullin |

Mikvaot |

Terumah |

|||

|

Demai |

Moed Katan |

Toharot |

|||

|

Ediyyot |

Nedarim |

Yadayim |

|||

|

Eruvin |

Nega’im |

Yevamot |

|||

|

Gittin |

Niddah |

Yoma |

|||

|

Horayot |

Ohalot |

Zevahim |

|||

|

Kallah |

Orlah |

||||

|

Kelim |

Peah |

||||

|

Midrash, Kabbalah, and Other Traditional Sources |

|||

|

Alef-Bet ben Sira |

Midrash Tehillim (Psalms) |

||

|

Avot de-Rabbi Natan |

Mishneh Torah |

||

|

Antiquities of the Jews (Josephus) |

Numbers Rabbah |

||

|

Babylonian Talmud |

De Opifico Mundi |

||

|

Sefer ha-Bahir |

Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer |

||

|

Beit ha-Midrash |

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana |

||

|

Charba de Moshe |

Papyri Graecae Magicae |

||

|

Deuteronomy Rabbah |

Pesikta Rabbati |

||

|

Dialogues |

Ruth Rabbah |

||

|

Ecclesiastes Rabbah |

Shulchan Aruch |

||

|

Enoch (I, II, III) |

Sefer Chasidim |

||

|

Esther Rabbah |

Seder Gan Eden |

||

|

Exodus Rabbah |

Shivhei ha-BeSHT |

||

|

Ein Yaakov |

Sefer ha-Razim |

||

|

Genesis Rabbah |

Sifra |

||

|

Jerusalem Talmud |

Sifre Deuteronomy |

||

|

Lamentations Rabbah |

Song of Songs Rabbah |

||

|

Leviticus Rabbah |

Sefer Yetzirah |

||

|

Legends of the Jews |

Midrash Tanhuma |

||

|

Mishnah |

Midrash Tanhuma (Buber) |

||

|

Mekhilta de Rabbi Ishmael |

Tanna de Eliyahu |

||

|

Masekhet Gehinnom |

Tosefta |

||

|

Midrash ha-Gadol |

Tikkunei Zohar |

||

|

Midrash Avkir |

The Jewish War (Josephus) |

||

|

Midrash Konen |

Yalkut Shimoni |

||

|

Midrash Mishlei (Proverbs) |

Zohar Chadash |

||

|

Midrash Samuel |

Sefer ha-Zohar |

||

Systems for citations vary from one Jewish document to the next. Citations such as “8a” and “8b” refer to the front and flip side of a folio page. Hebrew citations following the title of a Midrashic work, such as “Yitro,” refer to the parshiyot, or traditional divisions of Torah, which run many pages and will require further browsing. Short documents will often not include more page-specific citations.

Quick Reference Glossary

Of Frequently Used Terms

Aggadah: Stories, narratives, and legends; all the nonlegal materials in rabbinic literature.

Apotropaic: Protective.

BCE/CE: “Before the Common Era/Common Era.” These dating designations coincide with the Christocentric dating system of “BC/AD.” Thus, 1497 CE is the same as 1497 AD.

Bible: For the purposes of this encyclopedia, “Bible” refers to the Hebrew canonical Bible, also called TaNaKH, consisting of thirty-nine books and being effectively identical to the Christian “Old Testament.”

Classical Antiquity: For the purposes of this encyclopedia, the period from about 500 BCE to 200 CE.

Early Judaism: The spiritual expressions of the Jewish people from the end of the Babylonian exile (516 BCE) until the rise of the Sages (200 CE).

Gloss: An interpretation, clarification, or comment inserted into an earlier text by a later copyist. This phenomenon occurs throughout classical Jewish literature, making every document, including the Bible, a work of composite authorship.

Greco-Roman Period: For the purposes of this encyclopedia, from 300 BCE to 500 CE.

Hermetic: Refers to the teachings and disciplines of Western non-Jewish magic most closely associated with alchemy and the Islamic-Renaissance fusion of astronomy and magic.

Kabbalah: A Jewish mystical movement of the 12th to 16th centuries, but also used as a catchall term for Jewish mysticism.

Medieval Period: For the purposes of this encyclopedia, the period from the Muslim conquests (8th century) until the Reformation (16th century).

Midrash: Homiletic and legal interpretations of the Bible, usually collected into books.

Mishna, Or Mishnah: The core document of the Talmud and the first great text of rabbinic Judaism, compiled around 200 CE.

Modern: For the purposes of this encyclopedia, the 17th to 20th centuries.

Numinous: Spiritual forces and entities of an awesome and/or terrifying aspect.

Parsha, Parshiyot: The traditional/medieval system of dividing the Torah into fifty-four sections.

Persian Period: A period lasting from 500 BCE to 300 BCE.

Prophylactic: Preventative protection.

Rabbinic Literature: All literary writings of the Sages and their immediate successors (100 BCE-1100 CE), such as Mishnah, Talmud, and the Midrashim.

Rabbinic Period: The period when the Sages came to define Jewish spiritual practice. Though the first of the Sages emerged around 200 BCE, their influence really peaked from about 200 CE to the Islamic conquests of the 8th century. This roughly coincides with the period dubbed “Late Antiquity.”

Renaissance: For the purposes of this encyclopedia, the 15th through early 17th centuries.

Sages: The Rabbis of the Talmudic and immediate post-Talmudic eras who defined rabbinic Judaism.

Talmud: The Mishnah combined with its vast commentaries (Gemara). There are two versions of the Talmud, the Babylonian and the Palestinian (or Jerusalem) versions, compiled over the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

Targum: An early translation of the Bible from Hebrew, usually into Aramaic. The translations are often packed with interpretative glosses, paraphrases, and unusual readings.

Tellurian: Of subterranean, underground, or underworld origins.

Theosophy: Any philosophic system based on mystical or extra-rational insight into the nature of God and the universe.

Theurgy: The word theurgy comes from the practices of Egyptian Neoplatonists. For the purposes of this encyclopedia, I distinguish theurgic from magical practices when the ritual or act involves invoking/adjuring and influencing sentient spirits (including angels, demons, or even a name of God).

Torah: The Five Books of Moses; the first five books of the Bible, and the spiritual “Constitution” of the Jewish people. The word can also be used as a metonym for the full scope of all Jewish teachings, or even as a synonym for “Judaism.”