The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition (2016)

K

Kabbalah: (![]() ). “[Esoteric] Tradition.” “Kabbalah” (sometimes translated as “mysticism” or “occult knowledge”) is a part of Jewish tradition that is preoccupied with “inner” meaning. Whether it entails a text, an experience, or the way things work, Kabbalists believe that the world does not wear its heart on its sleeve, that God truly moves in mysterious ways. But true knowledge and understanding of that inner, mysterious process is obtainable, and through that knowledge, the greatest intimacy with God is attainable.

). “[Esoteric] Tradition.” “Kabbalah” (sometimes translated as “mysticism” or “occult knowledge”) is a part of Jewish tradition that is preoccupied with “inner” meaning. Whether it entails a text, an experience, or the way things work, Kabbalists believe that the world does not wear its heart on its sleeve, that God truly moves in mysterious ways. But true knowledge and understanding of that inner, mysterious process is obtainable, and through that knowledge, the greatest intimacy with God is attainable.

Technically, the term “Kabbalah” only applies to the form of Jewish occult gnosis that emerged in medieval Spain and Provence from the 12th century on. Jews outside the circle of academia, however, use the term “Kabbalah” as a catchall for Jewish esotericism in all its forms.

The distinctive perspective that Kabbalists bring to their intellectual enterprise, the one that makes it “mysticism,” which is the desire to experience intimacy with God, is the tendency to see the Creator and the Creation as on a continuum, rather than as discrete entities. This is especially true with regards to the powerful mystical sense of kinship between God and humanity. Within the soul of every individual is a hidden part of God that is waiting to be revealed. And even mystics who refuse to so boldly describe such a fusion of God and man nevertheless find the whole of Creation suffused in divinity, breaking down distinctions between God and the universe. Thus, the Kabbalist Moses Cordovero writes, “The essence of divinity is found in every single thing, nothing but It exists … It exists in each existent.”

There are three dimensions to almost all forms of Jewish esotericism: the investigative, the experiential, and the practical. The first dimension, that of investigative Kabbalah, involves the quest for gnosis, or special knowledge: plumbing the hidden reality of the universe (the nature of the Godhead), understanding the cosmogony (origins), and cosmology (organization) of the universe, and apprehending the divine economy of spiritual forces in the cosmos. This is, technically speaking, an esoteric discipline more than it is a mystical one, which is to say, its more about acquiring secret knowledge than it is experiencing God directly.

So how does the speculative Kabbalist come by his special insight into the inner workings of God and world? There are fundamentally three ways in which esoteric knowledge is obtained in Jewish tradition:1

1. Through textual interpretation which uncovers nistar, or “hidden” meaning

2. Through the traditions transmitted orally by a Kabbalistic master

3. By means of some sort of direct revelation. Examples of this include visitation by an angel, or Elijah, by spirit possession, or other supra-rational experience.

Although it is primarily interested in metaphysics, things “beyond” the physical universe, it would be a grave mistake to say that investigative Kabbalah is anti-rational. All Jewish mystical/esoteric traditions adopt the language of, and expand upon, the philosophic and even scientific ideas of their time.

The second dimension is the experiential, which entails the actual quest for mystical experience: a direct, intuitive, unmediated encounter with a close but concealed deity. As Abraham Joshua Heschel puts it, mystics “want to taste the whole wheat of spirit before it is ground by the millstones of reason.” The mystic specifically seeks the ecstatic experience of God, not merely knowledge about God. In their quest to encounter God, Jewish mystics live spiritually disciplined lives. While Jewish mysticism gives no sanction to monasticism, either formal or informal, experiential Kabbalists tend to be ascetics. And though Judaism keeps its mystics grounded—they are expected to marry, raise a family, and fulfill all customary communal religious obligations—they willfully expand the sphere of their pietistic practice beyond what tradition requires. Many Kabbalists create hanganot (“personal daily devotional practices”). Thus, in his will, one Kabbalist recommended this regime to his sons: periods of morning, afternoon, evening, and midnight Prayer; two hours devoted to the Bible, four and a half to Talmud, two to ethical and mystical texts, and two to other Jewish texts; one and a half hours to daily care, time to make a living—and five hours to sleep !

The third dimension is the practical, theurgic, or pragmatic Kabbalah (Kabbalah Maasit or Kabbalah Shimmush); the application of mystical power to effect change in our world, and the celestial worlds beyond ours. Practical Kabbalah consists of rituals for gaining and exercising power. It involves activating theurgic potential by the way one performs the commandments, the summoning and controlling of angelic and demonic forces, and otherwise tapping into the supernatural energies present in Creation. The purpose of tapping into the practical Kabbalah is to further God’s intention in the world: to advance good, subdue evil, heal, and mend. The true master of this art fulfills the human potential to be a co-creator with God.

Historians of Judaism identify many schools of Jewish esotericism across time, each with its own unique interests and beliefs.

As I noted above, Jewish mystics are not like monks or hermits. Kabbalists tend to be part of social circles rather than lone seekers. With few exceptions, such as the wandering mystic Abraham Abulafia, esoterically inclined Jews congregate in mystical brotherhoods and associations. It is not unusual for a single master to bring forth a new and innovative mystical school, which yields multiple generations of that particular mystical practice. While Kabbalah has been the practice of select Jewish “circles” up to this day, we know most of what we know from the many literary works that have been recognized as “mystical” or “esoteric.”

From these mystical works, scholars identify many distinctive mystical schools, including the Hechalot mystics, the German Pietist, the Zoharic Kabbalah, the ecstatic school of Abraham Abulafia, the teachings of Isaac Luria, and Chasidism. Scholars can break these groupings down even further based on individual masters and their disciples. Most mystical movements are deeply indebted to the writings of earlier schools, but as often as not, they add many innovative interpretations and new systems of thought to these existing teachings.

An important historical feature of Jewish esotericism is the tendency to compose mystical and esoteric works as pseudepigrapha—to portray a new revelation as the product of antiquity or of a particular worthy figure of the past. This is characteristic of many prominent mystical texts written before the dawn of the modern era, such as Hechalot texts, the Bahir, the Zohar, and of the writings of the Circle of the Unique Cherub. The practice of producing credited works only takes hold from the 15th to the 16th century onward. SEE CREATION; EMANATION; MEDITATION; SEFIROT; SUMMONING.

1. Fine, Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos, 99-100.

Kabshiel: (![]() ). Angelic name that appears on amulets.

). Angelic name that appears on amulets.

Kaddish: (![]() ). “Sanctification.” This Prayer of divine praise, which makes no mention of death, has become inextricably associated with memorializing the dead. In part, this association has arisen from a story told of Rabbi Akiba. In Seder Eliyahu Zuta, we learn that Akiba once encountered a ghost. The Sage inquired as to why the spirit could not find rest, so the ghost related that it was his punishment for having failed to religiously educate his son. Akiba then took it upon himself to teach the boy the prayer service. When the boy finally recited the words of Kaddish, his father’s soul was released (also see Sanh. 104a).

). “Sanctification.” This Prayer of divine praise, which makes no mention of death, has become inextricably associated with memorializing the dead. In part, this association has arisen from a story told of Rabbi Akiba. In Seder Eliyahu Zuta, we learn that Akiba once encountered a ghost. The Sage inquired as to why the spirit could not find rest, so the ghost related that it was his punishment for having failed to religiously educate his son. Akiba then took it upon himself to teach the boy the prayer service. When the boy finally recited the words of Kaddish, his father’s soul was released (also see Sanh. 104a).

Perhaps because of this incident, it has become the practice to recite Kaddish daily for a year after the death of a close relative, in the belief that it will ease the soul’s time in Gehenna, which can last up to a year. Customarily, a surviving relative says Kaddish for eleven months rather than the twelve of a full year, so as not to suggest to others that one considers the deceased so wicked that he or she deserved a full year of punishment. SEE DEATH.

Kaf: Eleventh letter of the Hebrew alphabet. The letter represents Keter, “crown,” the first emanation of the sefirot. It is also the first letter of the word karet, “cut off.” Every Jew potentially shares in this supernal crown when he or she chooses to embrace the “crowns” God has provided: the crown of Torah, of kingship, of the priesthood, or of a good name. By contrast, those Jews who utterly reject these crowns are spiritually cut off from both the power and blessings of God.1

1. Munk, The Wisdom of the Hebrew Alphabet, 133-37.

Kaf: (![]() ). “Hand/Palm.” SEE FINGER; HAND.

). “Hand/Palm.” SEE FINGER; HAND.

Kaf ha-Kela: (![]() ). “Sling Pocket.” One of the seven compartments of Gehenna. The name is derived from a biblical passage, “The souls of Your enemies shall be slung out, as from a kaf kela” (1 Sam. 25:29). In Kaf Kela, the punishing angels play, so to speak, a relentless game of lacrosse, tossing the souls of the transgressors back and forth as their game balls (Masechet Gehinnom). In Zohar, the term is taken to be an idiomatic term for the process of transmigration undergone by the impure soul (Zohar I:77b, 217b; Zohar II:59a, 99b).

). “Sling Pocket.” One of the seven compartments of Gehenna. The name is derived from a biblical passage, “The souls of Your enemies shall be slung out, as from a kaf kela” (1 Sam. 25:29). In Kaf Kela, the punishing angels play, so to speak, a relentless game of lacrosse, tossing the souls of the transgressors back and forth as their game balls (Masechet Gehinnom). In Zohar, the term is taken to be an idiomatic term for the process of transmigration undergone by the impure soul (Zohar I:77b, 217b; Zohar II:59a, 99b).

Kaftzefoni: (![]() ). A demon and occasional consort of Lilith (Treatise on the Left Emanation).

). A demon and occasional consort of Lilith (Treatise on the Left Emanation).

Kaftziel: (![]() ). Planetary Angel of Saturn (SY; Sefer Raziel). He is prominently featured in this Hebreo-Arabic astrological-magic text:

). Planetary Angel of Saturn (SY; Sefer Raziel). He is prominently featured in this Hebreo-Arabic astrological-magic text:

On the seventh day rules Qaphsiel. This angel is of bad augury, for he is appointed only over evil. He is in the likeness of a man in mourning, and has two horns, and angel servants as the other angels aforementioned … If thou wishes to make use of them to lower a man from his high position, make a tablet of tin and draw on it the likeness of an old man with out stretched hands; under his right hand draw the image of a little man, and write on his forehead Qubiel; on the left, the image of a man crying … The use of this tablet is that if thou placest it on the seat of a mighty man, or a king, or a priest, he will fall from his position, and if thou puttest it in a place where many people are assembled, they will scatter and go away from that spot. If thou placest it in a spot where they are building a town, or a tower, it will be destroyed … (Gaster, Wisdom of the Chaldeans)

Kahana: Talmudic Sage (ca. 3rd-4th century). His beauty was compared to that of Adam. After slaying a government spy in Babylonia, he fled to the Land of Israel to the circle of R. Yochanan. In a karmic turn, a fit of annoyance, Rabbi Yochanan slew him with the evil eye, but later resurrected him. After that, Kahana opted to leave Yochanan’s academy (B.K. 117a-b).

Kalonymus (or Qalonymus) Family: This dynasty of medieval Rhineland Jews produced a line of distinguished rabbis. They also had their own familial collection of esoteric traditions that shaped the teachings of the German Pietist.1

1. Green, Jewish Spirituality, vol. 1, 356.

Kamia: (![]() ). “Amulet.” A charm or talisman. SEE AMULET.

). “Amulet.” A charm or talisman. SEE AMULET.

Kapkafuni: (![]() ). A possessing demons queen mentioned in a medieval Jewish exorcism text (Shoshan Yesod ha-Olam).

). A possessing demons queen mentioned in a medieval Jewish exorcism text (Shoshan Yesod ha-Olam).

Kapparah: (![]() ). “Expiation.” In the theurgic ceremony of kapparah, performed on the eve of Yom Kippur, traditional Jews transfer their sin to a bird by waving it around their heads three times while reciting the words, “This bird is my surrogate, my substitute, my atonement; this cock shall meet death, but I shall find a long and pleasant life of peace.” Then the animal, usually a chicken, is slaughtered and donated to the poor. First mentioned in the literature of the Gaonic period (9th century CE), the practice has enjoyed popular support for centuries, despite the disapproval of many prestigious rabbinical authorities such as Nachmanides and Joseph Caro. Most modernist Orthodox Jews opt to replace the hen with a sack of cash, which is then given as charity.

). “Expiation.” In the theurgic ceremony of kapparah, performed on the eve of Yom Kippur, traditional Jews transfer their sin to a bird by waving it around their heads three times while reciting the words, “This bird is my surrogate, my substitute, my atonement; this cock shall meet death, but I shall find a long and pleasant life of peace.” Then the animal, usually a chicken, is slaughtered and donated to the poor. First mentioned in the literature of the Gaonic period (9th century CE), the practice has enjoyed popular support for centuries, despite the disapproval of many prestigious rabbinical authorities such as Nachmanides and Joseph Caro. Most modernist Orthodox Jews opt to replace the hen with a sack of cash, which is then given as charity.

Among the Jews of Kurdistan, a form of kapparah is performed at the birth of a child, and the blood of the slaughtered animal sprinkled in the birth room, evidently to protect the newborn from suffering the consequences of the sins of its parents. A similar practice for newlyweds is known to be an old German-Jewish practice.1 SEE COCK; SACRIFICE; SUBSTITUTION.; THEURGY

1. Sperber, The Jewish Life Cycle, 25, 301.

Karet: (![]() ).“Cut off/Extirpation.” A divine punishment mentioned in the Bible (Gen. 17:14), usually meted out for acts of gross disrespect toward heaven (desecrating the Shabbat, idolatry) or toward another person (incest, adultery). The Mishnah has a tractate, Keritot, which identifies thirty-six crimes that merit karet. Nachmanides believed being “cut off” referred to the soul being reincarnated in a more degraded Body (Commentary to Lev. 18:29). Isaac Luria taught it involved the lower soul (nefesh) being unable to make the journey into the afterlife and was the cause of ghosts and dybbuks (Zohar III:57b, 217a; Sha’ar ha-Gilgulim 4).

).“Cut off/Extirpation.” A divine punishment mentioned in the Bible (Gen. 17:14), usually meted out for acts of gross disrespect toward heaven (desecrating the Shabbat, idolatry) or toward another person (incest, adultery). The Mishnah has a tractate, Keritot, which identifies thirty-six crimes that merit karet. Nachmanides believed being “cut off” referred to the soul being reincarnated in a more degraded Body (Commentary to Lev. 18:29). Isaac Luria taught it involved the lower soul (nefesh) being unable to make the journey into the afterlife and was the cause of ghosts and dybbuks (Zohar III:57b, 217a; Sha’ar ha-Gilgulim 4).

Kasdiel: An Egyptian sorcerer, the father-in-law of the biblical Ishmael (Sefer Meir Tehillot 91).

Kastimon and Afrira: “Inquisitor and Dust.” A pair of demonic shape-changing notables, emissaries of light and dark who spring from the actions of Cain, who rule over the underworld of Arka. Like most binary entities in Kabbalah, they represent male and female (evil) forces. They resemble serafim and Chayyot, but also take on human and serpent form (Zohar I:9b).

Kastirin: (![]() ). “Tormentor.” A class of demons mentioned in the Zohar (Zohar I:20a).

). “Tormentor.” A class of demons mentioned in the Zohar (Zohar I:20a).

Katnut: (![]() ). “Naivity; small-mindedness.” In classic Kabbalah, this is the state of immature intellect, the precursor to mochin. It is Malchut seen from the perspective of the practitioner, the first step toward expanded consciousness. Nachman of Bratzlav reverses this judgment, teaching that it conveys a kind of humility, and katnut is the path to humble insight.1

). “Naivity; small-mindedness.” In classic Kabbalah, this is the state of immature intellect, the precursor to mochin. It is Malchut seen from the perspective of the practitioner, the first step toward expanded consciousness. Nachman of Bratzlav reverses this judgment, teaching that it conveys a kind of humility, and katnut is the path to humble insight.1

1. Liebes, Studies in Jewish Myth and Messianism, 119-22.

Kavanah: (![]() ). “Intention/Concentration.” Judaism teaches that proper intention is essential to meaningful Prayer (Yad. Tefillah 4:16; Hovot Levavot). The Kabbalists go further, teaching that developing the right state of mind is an absolute prerequisite for any religious act or ritual to have gevurah (“spiritual energy”). Kavvanot take on a theurgic role in activating and uniting the sefirot and/or Partzufim, the exact application varying from teacher to teacher. Often this kavanah requires extended meditation exercises. There are even techniques called kavanot to help achieve this concentration.1 Isaac Luria initiates this elaborate mystical practice of kavvanot, culminating in the Siddur Nusach ha-Ari and the techniques of the Beit El Circle. SEE MEDITATION; YICHUDIM.

). “Intention/Concentration.” Judaism teaches that proper intention is essential to meaningful Prayer (Yad. Tefillah 4:16; Hovot Levavot). The Kabbalists go further, teaching that developing the right state of mind is an absolute prerequisite for any religious act or ritual to have gevurah (“spiritual energy”). Kavvanot take on a theurgic role in activating and uniting the sefirot and/or Partzufim, the exact application varying from teacher to teacher. Often this kavanah requires extended meditation exercises. There are even techniques called kavanot to help achieve this concentration.1 Isaac Luria initiates this elaborate mystical practice of kavvanot, culminating in the Siddur Nusach ha-Ari and the techniques of the Beit El Circle. SEE MEDITATION; YICHUDIM.

1. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 275-77.

Kavanot, Sefer ha-: A collection of the teachings of Chayyim Vital , especially focusing on mystical meditations and Prayers and the cultivating of the right intention to make them efficacious, that is part of the larger work Eitz Hayyim. There are at least two other anthologies of mystical customs that go by the same name.

Kavod: (![]() ). SEE GLORY.

). SEE GLORY.

Kedushah or Kedushat ha-Shem: (![]() ). A liturgical Prayer that appears several times in the prayer book. The text is constructed from the various appearances of Angelsin the Bible and the words they spoke. One version, included in the prayer Yotzer Or, lists the classes of angels that attend upon God:

). A liturgical Prayer that appears several times in the prayer book. The text is constructed from the various appearances of Angelsin the Bible and the words they spoke. One version, included in the prayer Yotzer Or, lists the classes of angels that attend upon God:

Then the Ophanim and the holy Chayyot, with great noise raise themselves towards the Seraphim. Facing them they give praise saying: “Blessed is the glory of Adonai from His place.”

The goal of the prayer is mimetic, for the congregation to mirror, and in essence, become one with the angelic choirs in their praise of God. In their astral ascensions, Merkavah mystics and German Pietist took a particular interest in the music of the angels when they recited their kedushah praises to God. The ascendant mystic would learn these melodies to bring them back to Earth for use in the synagogue.1

1. Schafer, The Hidden and Manifest God, 46-49. Also see Wolfson, Through a Speculum that Shines.

Kefitzat ha-Derech: (![]() ). “Bounding of the Path.” SEE TELEPORTATION.

). “Bounding of the Path.” SEE TELEPORTATION.

Kelach Pitchei Chochmah: “One Hundred and Thirty-Eight Openings of Wisdom.” A Kabbalistic treatise by Moses Luzzato giving special attention to the architecture of the soul.

Kelipot: (![]() ). “Husks.” Remnants of the cosmic tragedy associated with the fall of Adam Kadmon, these husks of evil encase the scattered sparks of divine holiness that must be released by humanity and restored to their divine source through the spiritual process of Tikkun (Zohar I:4b; Sha’ar ha-Gilgulim 3; Sefer ha-Tikkunim). According to the Zohar, they exist in four strata (I: 19b). Their existence is utterly dependent upon human action, and they are fed and strengthened by human transgression. Later Kabbalistic thought develops a taxonomy of different types of kelipot, including the nogah, an admixture of good and evil that energizes all demonic forces. (Zohar I:1a; Tanya 1-2). The most powerful of all kelipot, their organizing principle, is personified as Samael. Later Chasidic thinkers start to distinguish between redeemable (kelipot nogah) and unredeemable kelipot (Tanya, Igeret Teshuvah 6-7). SEEBREAKING OF THE VESSELS; NITZOTZ.

). “Husks.” Remnants of the cosmic tragedy associated with the fall of Adam Kadmon, these husks of evil encase the scattered sparks of divine holiness that must be released by humanity and restored to their divine source through the spiritual process of Tikkun (Zohar I:4b; Sha’ar ha-Gilgulim 3; Sefer ha-Tikkunim). According to the Zohar, they exist in four strata (I: 19b). Their existence is utterly dependent upon human action, and they are fed and strengthened by human transgression. Later Kabbalistic thought develops a taxonomy of different types of kelipot, including the nogah, an admixture of good and evil that energizes all demonic forces. (Zohar I:1a; Tanya 1-2). The most powerful of all kelipot, their organizing principle, is personified as Samael. Later Chasidic thinkers start to distinguish between redeemable (kelipot nogah) and unredeemable kelipot (Tanya, Igeret Teshuvah 6-7). SEEBREAKING OF THE VESSELS; NITZOTZ.

Kelonymus Baal ha-Nes: Wonderworking rabbi (Israel, ca. 17th century). This Jerusalem rabbi miraculously restored a Christian child to life using the Tetragrammaton. In doing so, he thwarted an attempt to blame the Jews of Jerusalem for a blood libel. Pilgrims still visit his grave on the Mount of Olives, believing his merit will ensure their safe return home.

Kemuel: ( ![]() ). Angel who guards the gates of heaven (Gedulat Moshe). While Moses was receiving the Torah in heaven, Kemuel attempted to expel him. Moses was forced to destroy him (PR 20; BhM 1:58-60; Ir El Gibborim piyut).

). Angel who guards the gates of heaven (Gedulat Moshe). While Moses was receiving the Torah in heaven, Kemuel attempted to expel him. Moses was forced to destroy him (PR 20; BhM 1:58-60; Ir El Gibborim piyut).

Kenahora: ([rahanyyq). “No evil eye!” A Yiddish exclamatory incantation used to thwart the evil eye when one feels vulnerable to its attack.

Kerubiel: ( ![]() ). “[Supreme] Cherub of God.” Chief Angel of the Cherubs. He is robed in the rainbow (III Enoch 22).

). “[Supreme] Cherub of God.” Chief Angel of the Cherubs. He is robed in the rainbow (III Enoch 22).

Keshet: (![]() ). “Bow.” Sign of the Hebrew zodiac for the month of Kislev (Sagittarius). A symbol of both peace (Gen. 9) and war, it signifies the varied interaction of Jews and non-Jews; it symbolizes both Joseph, who thrived in a foreign land, and Chanukah, which exemplified conflict with gentiles.1 SEE BOW.

). “Bow.” Sign of the Hebrew zodiac for the month of Kislev (Sagittarius). A symbol of both peace (Gen. 9) and war, it signifies the varied interaction of Jews and non-Jews; it symbolizes both Joseph, who thrived in a foreign land, and Chanukah, which exemplified conflict with gentiles.1 SEE BOW.

1. Erlanger, Signs of the Times, 161-98.

Kesilim: (![]() ). “Fools/Imps.” Impish spirits. Belief in these creatures is derived from a supernatural interpretation of Proverbs 14, which speaks of the misleading ways of the kesilim (Emek ha-Melech).

). “Fools/Imps.” Impish spirits. Belief in these creatures is derived from a supernatural interpretation of Proverbs 14, which speaks of the misleading ways of the kesilim (Emek ha-Melech).

Ketem Paz: A commentary on the Zohar by Shem Tov ibn Gaon.

Keter: (![]() ). “Crown.” The “highest” of the sefirot, it is the first to emerge from the Ein Sof. It is the intentionality, the desire of the Ein Sof to bring forth Creation. It is usually conceived in terms of paradox, such as “hidden light,” or via negativa, by describing only what it is not; it is “no thing.” The divine name El Elyon (“God most High”) is linked to Keter. It is also equated with Arikh Anpin in the Lurianic theory of Partzufim.

). “Crown.” The “highest” of the sefirot, it is the first to emerge from the Ein Sof. It is the intentionality, the desire of the Ein Sof to bring forth Creation. It is usually conceived in terms of paradox, such as “hidden light,” or via negativa, by describing only what it is not; it is “no thing.” The divine name El Elyon (“God most High”) is linked to Keter. It is also equated with Arikh Anpin in the Lurianic theory of Partzufim.

Keter Malchut: ( ![]() ). “Crown of kingship.” A critical, yet undefined mystical attribute of the Messiah, it is also the name of a treatise on astrology written by Solomon Gabirol.

). “Crown of kingship.” A critical, yet undefined mystical attribute of the Messiah, it is also the name of a treatise on astrology written by Solomon Gabirol.

Ketev Meriri: A demon (Pes. 111b). SEE BITTER DESTRUCTION.

Keturah: The wife taken by Abraham after the death of Sarah (Gen. 22), the Sages teach that she is actually Hagar, Abraham’s maidservant and father of his first child, Ishmael (Gen. R. 61).

Key: (![]() ). According to Sanhedrin 113a, God possesses three keys: to rain, to childbirth, and to resurrection. All other keys God has given over to “messengers” (i.e., angels and humanity), but these three remain God’s sole prerogative (Also see Tan. 2a).

). According to Sanhedrin 113a, God possesses three keys: to rain, to childbirth, and to resurrection. All other keys God has given over to “messengers” (i.e., angels and humanity), but these three remain God’s sole prerogative (Also see Tan. 2a).

Metatron possesses twelve of these keys:

Twelve celestial keys are entrusted to Metatron through the mystery of the holy name, four of which are the four separated secrets of the lights … And this light, which rejoices the heart, provides the illumination of wisdom and discernment so that one may know and ponder. These are the four celestial keys, in which are contained all the other keys, and they have all been entrusted to this supreme head, Metatron, the great prince, all of them being within his Master’s secrets, in the engravings of the mysteries of the holy, ineffable name.1

In the Zohar, this is magnified to six hundred and thirteen, or even one thousand keys:

All the supernal secrets were delivered into his hands and he, in turn, delivered them to those who merited them. Thus, he performed the mission the Blessed Holy One assigned to him. One thousand keys were delivered into his hands and he takes one hundred blessings every day and creates unifications for his Master (Zohar I:37b, 181a, 223b; Zohar III:60a).

The angel Yechdiah has the keys to the divine treasury (III: 129a).

In Midrash Pesikta Rabbati, at the time of the Roman destruction of the Second Temple, the High priest cast the keys to the building up toward heaven where they were caught by an angelic hand. The High Priest then offered the sacred Temple vessels (or instruments) to the Earth and the ground swallowed them up. When the Messiah comes, all these Temple articles will be and restored.

1. I. Tishby, The Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. II (New York: B’nai Brith Books, 1989), 644.

Key of Solomon: (Mafteach Shlomo). A late-medieval (14th century or later) magical text credited to Solomon and devoted primarily to the summoning of Angels and demons and the construction of amulets. It describes the use of magical circles in some detail. There are multiple Hebrew and Latin versions and the book has Jewish, Hermetic, and Christian influences present. It’s magical diagrams have been widely appropriated for a variety of magical and Hermetic practices. SEE TESTAMENT OF SOLOMON.

Khazars: A Turkish-speaking tribe of the Crimean-Central Asian regions that purportedly converted to Judaism in the early Middle Ages (ca. 740 CE). This Jewish kingdom survived for over a century until overwhelmed by the expanding Rus peoples from the north, spawning numerous legends.1

A popular anti-Jewish myth circulating among anti-Semitic groups is that modern Jews from eastern Europe are not Semites at all, and have no relationship to the ancient Jews of the Bible. Rather, we are all really Turkish descendants of the Khazars (and therefore somehow “pseudo” Jews), despite historical, demographic, linguistic, and, most recently, genetic evidence that reveal the specious nature of this claim.2

1. Roth, Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 10, 944-49.

2. M. Hoffman, Campaign for Radical Truth in History, http://www. hoffman-info.com.

Kiddush: (![]() ). The ritual for initiating a Sabbath or holiday by reciting a blessing over wine. Once blessed, Kiddush wine is believed to have medicinal power (Beit Yosef, Orach Chayyim 269). The kiddush l’vanah (“Sanctification of the [new] moon,” in particular, was thought to have theurgic power, a belief that first appears in Zohar III:95a, then took hold over European Jews sometime in the 17th century.

). The ritual for initiating a Sabbath or holiday by reciting a blessing over wine. Once blessed, Kiddush wine is believed to have medicinal power (Beit Yosef, Orach Chayyim 269). The kiddush l’vanah (“Sanctification of the [new] moon,” in particular, was thought to have theurgic power, a belief that first appears in Zohar III:95a, then took hold over European Jews sometime in the 17th century.

Kiddush L’vanah: (![]() ). “Sanctifying/Blessing the Moon.” SEE NEW MOON.

). “Sanctifying/Blessing the Moon.” SEE NEW MOON.

Kiddushat ha-Shem: ( ![]() ). “Sanctifying the Name.” The act of accepting martyrdom rather than refute one’s faith. The willingness to accept Death rather than deny a doctrine or commandment of Judaism has been celebrated in Jewish tradition since the example set by Daniel and his companions in the Bible. Naturally, most Jews facing martyrdom have not enjoyed the miraculous deliverances recorded for those biblical worthies. Nevertheless, anyone who dies to honor God is declared “holy,” and by the medieval period, artifacts associated with them, their gravesites, and even their names, were believed to be imbued with great spiritual power. The martyrs themselves can expect an exalted place in Eden. SEE LAMED-VAVNIKS; RIGHTEOUS, THE; TEN MARTYRS.

). “Sanctifying the Name.” The act of accepting martyrdom rather than refute one’s faith. The willingness to accept Death rather than deny a doctrine or commandment of Judaism has been celebrated in Jewish tradition since the example set by Daniel and his companions in the Bible. Naturally, most Jews facing martyrdom have not enjoyed the miraculous deliverances recorded for those biblical worthies. Nevertheless, anyone who dies to honor God is declared “holy,” and by the medieval period, artifacts associated with them, their gravesites, and even their names, were believed to be imbued with great spiritual power. The martyrs themselves can expect an exalted place in Eden. SEE LAMED-VAVNIKS; RIGHTEOUS, THE; TEN MARTYRS.

Kinder Benimmerins: (![]() ). Bloodlusting witches who slay children:

). Bloodlusting witches who slay children:

The Blind Dragon is between Samael and the Evil Lilith. And he brings about a union between them only in the hour of pestilence, the Merciful One save us! … And this Lilith has fourteen evil times and evil names and evil factions. And all [her offspring] are ordained to kill the children—may we be saved!—and especially through the witches who are called Kinder Benimmerins in the language of the Ashkenaz. (Emek ha-Melech 140b, trans. from Gates of the Old City 81)

Kingdom of God: ( ![]() /Malchut Shaddai, also Malchut Shamayim). This concept has multiple connotations, including the individual act of cleaving to God (Deut. R. 2:31), but usually refers to the advent of the Messiah and the Messianic Era. A brief summary of the main ideas is this: At a time deemed appropriate to God, based on either the radical improvement or the radical decline of the human moral condition, there will be a final reconciliation (tikkun olam) of the world’s political and social order with the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth under the leadership of the Messiah. The nations will be brought into harmony and the recognition of God’s dominion will be complete, making an end to war, exploitation, and inequity. This period will mark the restoration of the Davidic dynasty to Israel, the return of Prophecy, and, for all intents and purposes, the end of history. At some point during this Messianic kingdom, the natural order and human nature as we now know it will be radically transformed. The dead, having already made preliminary journeys through the afterlife, will be restored to a perfected bodily existence through resurrection, brought to final judgment, and those who merit it will live out an ideal life. After Death the individual soul will dwell in eternal bliss in the presence of God. SEE ESCHATOLOGY; KADDISH; WORLD TO COME.

/Malchut Shaddai, also Malchut Shamayim). This concept has multiple connotations, including the individual act of cleaving to God (Deut. R. 2:31), but usually refers to the advent of the Messiah and the Messianic Era. A brief summary of the main ideas is this: At a time deemed appropriate to God, based on either the radical improvement or the radical decline of the human moral condition, there will be a final reconciliation (tikkun olam) of the world’s political and social order with the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth under the leadership of the Messiah. The nations will be brought into harmony and the recognition of God’s dominion will be complete, making an end to war, exploitation, and inequity. This period will mark the restoration of the Davidic dynasty to Israel, the return of Prophecy, and, for all intents and purposes, the end of history. At some point during this Messianic kingdom, the natural order and human nature as we now know it will be radically transformed. The dead, having already made preliminary journeys through the afterlife, will be restored to a perfected bodily existence through resurrection, brought to final judgment, and those who merit it will live out an ideal life. After Death the individual soul will dwell in eternal bliss in the presence of God. SEE ESCHATOLOGY; KADDISH; WORLD TO COME.

Kings, Books of: The books Kings I and II contain many of the most famous miracles recorded in the Bible, outside those of the Torah. The central Prophets of the books, Elijah and Elisha, are conspicuous wonderworkers, doing things as minor as levitating iron in water , to feats as dramatic as resurrecting the dead.

Kipod: (![]() ). Demon prince; guardian of a gate of Gehenna (MG).

). Demon prince; guardian of a gate of Gehenna (MG).

Kiss: (![]() ). The kiss as a spiritual act has a long history in Judaism. It is closely linked with the handling and learning of Torah. Jews often kiss a Torah scroll when it is brought into the congregation. People will kiss a Chumash or siddur that has been dropped. Students would kiss the hand of their master after a learning session, symbolically acknowledging the hand that “fed” them spiritual sustenance (PdRE 2; Zohar III:147a). Masters would kiss disciples on the head as a kind of initiation ritual (T. Chag. 2:2). In the Zohar, in particular, masters would kiss students, often on the eyes, when they had demonstrated an insight or high attainment of wisdom.1 A kiss constitutes the fusion of spirit to spirit (II:124b).

). The kiss as a spiritual act has a long history in Judaism. It is closely linked with the handling and learning of Torah. Jews often kiss a Torah scroll when it is brought into the congregation. People will kiss a Chumash or siddur that has been dropped. Students would kiss the hand of their master after a learning session, symbolically acknowledging the hand that “fed” them spiritual sustenance (PdRE 2; Zohar III:147a). Masters would kiss disciples on the head as a kind of initiation ritual (T. Chag. 2:2). In the Zohar, in particular, masters would kiss students, often on the eyes, when they had demonstrated an insight or high attainment of wisdom.1 A kiss constitutes the fusion of spirit to spirit (II:124b).

In the highest heaven, the Angels who serve before the Throne of Glory kiss God during the afternoon worship. God too, kisses (S of S 1:1), in one case, the image of the Patriarch Jacob engraved upon the Throne of Glory:

I [God] bend over it, embrace, kiss and fondle it [the image of Jacob] and my hands are upon its arms, three times, when you speak before me “holy.” As it is said: holy, holy, holy. (Schafer, Synopse #64)

A special category of kiss is the kiss of God (Meitah be-nesikah in Hebrew or mise binishike in Yiddish, both of which are literally “kiss of death”). This refers to Death directly at the hands of God (or the Shekhinah):

930 kinds of death were created in the world … The most difficult is plague, the easiest of all is a kiss. Plague is like burr being pulled through a wool fleece or like stalks in your throat. A kiss is as gentle as drawing a hair out of milk. (Ber. 8a)

The concept arises from the death of Moses, where it is said he died al pi Adonai, “at God’s command,” but literally “upon God’s mouth” (Deut. 34). This easiest of all deaths circumvents the dreaded Angel of Death. According to the Sages, only six people have died this way: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Miriam, Aaron, and Moses (B.B. 17a; S of S R. 1:2; Tanh. Va-Etchanan). The corpses of those who die via the divine kiss do not defile the living who touch them with ritual impurity (Nachmanides, comment to Num. 19:2). In later Jewish mystical writings, a number of kabbalistic masters die in ecstasy via the “kiss” (Zohar III:144b; Sha’ar ha-Gilgulim 39). Jewish mysticism also equated the “kiss” with devekut, mystical fusion with God (Zohar II:53a).

1. A. Green, “Introducing the Pritzker Edition Zohar” (lecture, Convention of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, Toronto, June 2004).

Kleidon: Listening to children at study to hear omens in the verses they recite. SEE DIVINATION

Knesset Yisrael: ( ![]() ).“The Assembly of Israel.” The idealized, transpersonal collectivity of the Jewish people (Ket. 118a). Over time the connotation of the term evolves, and Knesset Israel is elevated by the Sages to be a hypostatic entity, a feminine counterpart to God:

).“The Assembly of Israel.” The idealized, transpersonal collectivity of the Jewish people (Ket. 118a). Over time the connotation of the term evolves, and Knesset Israel is elevated by the Sages to be a hypostatic entity, a feminine counterpart to God:

Whoever does not bless after the meal is described as looting his father and mother; The former is the Blessed Holy One, the latter is Knesset Israel. (Ber. 35b) [Also see Eruv. 21b and S o S R. 3:15-19]

Sometimes Rachel serves as the personification of the people. This particular hypostasis can take on a decidedly erotic tone:

Israel is beloved! … This can be compared to a king who said to his wife: adorn yourself in jewelry so that you may be desirable to me … So the Blessed Holy One said to Israel, “my children, adorn yourself with mitzvot so that you will be desirable to Me.” (Sif. D. 36)

In Kabbalah it becomes a synonym for Shekhinah (Zohar III:6a, 79a-b, 187b).

Knives: Knives are a symbol of power and force and as such are sometimes used in theurgic rites. The fact that they are made from metal, especially iron, only enhances their magical potential:

R. Johanan said: For an inflammatory fever let one take an all-iron knife, go whither thorn-hedges are to be found, and tie a white twisted thread thereto. On the first day he must slightly notch it, and say, “and the angel of the Lord appeared unto him,” etc. On the following day he [again] makes a small notch and says, “And Moses said, I will turn aside now, and see,” etc. The next day he makes [another] small notch and says, “And when the Lord saw that he turned aside [Sar] to see.” R. Aha son of Raba said to R. Ashi, Then let him say, “Draw not nigh hither?” [i.e., “Fever, leave the victim and come into the bush”]. (Shab. 67a)

Here the knife serves in a ritual for healing. There seems to be a special relationship between knives and the demonic: the Angel of Death is sometimes portrayed as wielding a butcher’s knife (J. Ket. 7:10), and knives are used for summoning demons and as a magical defense against evil spirits.1

Knives are often used in the creation of magic circles. A knife under a pillow will protect a childbearing woman against demonic attack. Specially constructed blades hum when poison is present. Knives are also used in casting curses.

1. Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic and Superstition, 114, 298.

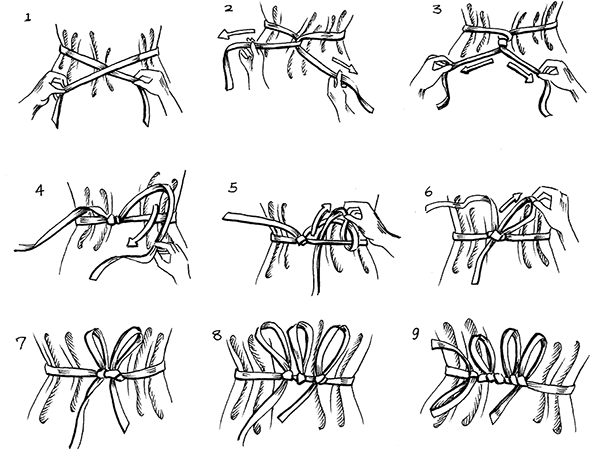

Tying knots on a death shroud

Knots: Knots represent the power to restrict and restrain. The knotted fringes commanded to be worn by the Israelites in the book of Numbers are symbolic reminders that the Jews have “bound” themselves to God even as the fringes are conduits of divine power. Knots were used in Greco-Roman magic as a sympathetic act in cursing rituals. In Jewish esoteric lore, this constricting capacity especially manifests itself in issues of fertility. Therefore, one should avoid knots around brides or women in childbirth. Seven loops of knots can fend off witchcraft (Shab. 66a). Knots tied to the left arm combined with incantations can curb obsessive behavior and “longing.” Various rituals of using knots for protection can be found among different Jewish communities in the Middle Ages.1 In many communities even today, special knots, tied so as to resemble the Hebrew letters shin, dalet, and yud are bound to the shrouds of a corpse during its preparation for burial, apparently so the spirits and Angels would recognize the deceased as a Jew, one who belongs to SHaDaY. SEE KOSHER FODEM.

1. Frankel, The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols, 92.

Kochviel: ( ![]() ). “Prince of Stars.” He is an angel that falls from heaven after lusting for the daughters of humanity. He taught humanity the art of astrology (I Enoch).

). “Prince of Stars.” He is an angel that falls from heaven after lusting for the daughters of humanity. He taught humanity the art of astrology (I Enoch).

Kohan: SEE PRIESTHOOD AND PRIEST.

Kohen Brothers: SEE JACOB BEN JACOB HA-KOHEN; ISAAC BEN JACOB HA-KOHEN.

Kohen, Naphtali: Wonderworking rabbi (German, ca. 17th century). A master in the use of divine names, he magically protected the communities he served from fires. He also possessed a ring of power like the one owned by Solomon, and used it to exorcise demons. At the end of his life, he became mentally unbalanced.

Komm: (![]() ). An Angel who guides Joshua ben Levi on a tour of Gehenna (BhM II: 48-51).

). An Angel who guides Joshua ben Levi on a tour of Gehenna (BhM II: 48-51).

Korach ben Izhar: This biblical rebel against the authority of Moses was swallowed up by the Earth for his effrontery (Num. 16:26).

According to the Sages, Korach was so arrogant because of being extraordinarily wealthy, having found treasures which Joseph had concealed. Just the keys of Korach’s treasuries burdened three hundred mules (Pes. 119a; Sanh. 110a).

Korach was simultaneously burned and buried alive (Tanh. Korach 23). When the ground swallowed up Korach, the earth became like a vacuum, and everything that belonged to him, even his possessions that had been borrowed by persons far away, found their way into the chasm (J. Sanh. 10:1; Num. R. 50). He and his followers burned in Gehenna until Hannah prayed for them (Gen. R. 98:3). Because of her merit, Korach will eventually have a place in Eden (AdRN 36; Num. R. 18:11). Rabbah bar Channah related that he was shown the place where Korach and his company went down. Listening to the crack in the earth, he heard voices saying: “Moses and his Torah are true; and we are liars” (B.B. 74a).

Kosem Kesamim: (![]() ). “Augurer/Diviner/Magician.” The biblical word (Deut. 18) is related to the Arabic, “to divide,” (i.e., drawing lots). Such individuals are often linked in Hebrew Scriptures with false prophecy. SEEDIVINATION

). “Augurer/Diviner/Magician.” The biblical word (Deut. 18) is related to the Arabic, “to divide,” (i.e., drawing lots). Such individuals are often linked in Hebrew Scriptures with false prophecy. SEEDIVINATION

Kosher: SEE FOOD.

Kosher Fodem: “Fit string.” An outgrowth of the Ashkenazi pious custom known variously as Kneytlekh Legn (“laying wicks”) or Korim Mesn (“measuring graves”). In Poland and other Eastern European communities, pious women would go, en mass, to graveyards and lay thread around the graves of people known for their piety in life. This seemingly morbid practice was actually a spirited and popular women’s outing.1 The string so prepared, was thought to “absorb” a measure of the dead soul’s merit. Most often, the strings would be cut into wicks, made into Candles, and then donated to a synagogue or house of study.

This was a charitable effort to support these sacred institutions, but it was also done out of “enlightened” self-interest. Commonly the donation would be made to coincide with High Holidays or an illness or trouble in the family, in hopes of receiving divine intercession. The candles could also be reserved for rituals of divination or as a means to protect the household against malevolent forces.2 No doubt, some of this string was simply attached to places of vulnerability one wanted to protect—a baby crib or birthing bed, for example. And some just got tied around the wrist.

1. M. Wex, Born to Kvetch: Yiddish Language and Culture in All of Its Moods (New York: Harper Perennial, 2005), 178.

2. Weissler, “Measuring Graves, and Laying Wicks,” 61-80.

Kriat Sh’ma al ha-Mitah: (![]() ). “Bedtime recitation of the Sh’ma.” In Deuteronomy 6, every Jew is commanded to meditate upon God’s unity when rising and when going to bed. Kriat Sh’ma al ha-Mitah is the ritual that fulfills that obligation (Siddur). The ritual also includes a number of protective Prayers and verses (Gen. 48:16), invoking God’s protection against bad dreams, illness, nighttime spirits, and asking the Shekhinah and the four Angels surrounding the Throne of Glory—Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel—to also guard the person while asleep. SEE SLEEP.

). “Bedtime recitation of the Sh’ma.” In Deuteronomy 6, every Jew is commanded to meditate upon God’s unity when rising and when going to bed. Kriat Sh’ma al ha-Mitah is the ritual that fulfills that obligation (Siddur). The ritual also includes a number of protective Prayers and verses (Gen. 48:16), invoking God’s protection against bad dreams, illness, nighttime spirits, and asking the Shekhinah and the four Angels surrounding the Throne of Glory—Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel—to also guard the person while asleep. SEE SLEEP.

Kuf: (![]() ). Nineteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It has the linguistic value of “k” and the numeric value of one hundred. It signifies holiness and circularity.1

). Nineteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It has the linguistic value of “k” and the numeric value of one hundred. It signifies holiness and circularity.1

1. Munk, The Wisdom of the Hebrew Alphabet, 194-98.

Kushiel or Koshiel: ( ![]() ). “Severity of God.” A punishing Angel of Gehenna, he governs one of the seven compartments, “Well of Destruction” (Mid. Konen).

). “Severity of God.” A punishing Angel of Gehenna, he governs one of the seven compartments, “Well of Destruction” (Mid. Konen).

Kvittel: ( ![]() ). A written request for spiritual guidance, healing, or miraculous intervention. Its roots are found in the Hebrew Bible (1 Sam. 9:6-8; Prov. 16:14) and Talmud (B.B. 116a; Ber. 34a). There are two forms of kvittel: the type inserted into a shrine, such as the Western Wall in Jerusalem (PdRE 35), and those sent by a Chasid to a Chasidic master. The text usually has a standard or stereotypical form. The latter type is normally accompanied by a pidyon nefesh, a donation meant for the upkeep of the master and his household (some rebbes were famed for refusing such gratuities as corrupting).

). A written request for spiritual guidance, healing, or miraculous intervention. Its roots are found in the Hebrew Bible (1 Sam. 9:6-8; Prov. 16:14) and Talmud (B.B. 116a; Ber. 34a). There are two forms of kvittel: the type inserted into a shrine, such as the Western Wall in Jerusalem (PdRE 35), and those sent by a Chasid to a Chasidic master. The text usually has a standard or stereotypical form. The latter type is normally accompanied by a pidyon nefesh, a donation meant for the upkeep of the master and his household (some rebbes were famed for refusing such gratuities as corrupting).

Sometimes the kvittel initiated a face-to-face audience, called a yechidut, with the rebbe. At other times, the tzadik would respond in writing. Their recipients treated such letters as spiritual relics. Kvittels are even written to dead saints and are left on the grave, in the belief that the spiritual intercession of that particular Righteous individual can transcend even death.1

1. Z. Schachter-Shalomi and E. Hoffman, Sparks of Light: Counseling in the Hasidic Tradition (Boulder, CO: Shambala, 1983), 83-84. Also see Z. Schachter-Shalomi, Spiritual Intimacy: A Study of Counseling in Hasidism (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1996).

Kvorim Mesn: (![]() ). “Measuring Graves.” The Ashkenazi custom of women measuring cemeteries and graves with candlewick. Having been exposed to the sanctity of meritorious ancestors, the wicks would then be cut and made into Candles to be used during the High Holy Days in rituals, divinations, and as protection against spirits.1 SEE KOSHER FODEM.

). “Measuring Graves.” The Ashkenazi custom of women measuring cemeteries and graves with candlewick. Having been exposed to the sanctity of meritorious ancestors, the wicks would then be cut and made into Candles to be used during the High Holy Days in rituals, divinations, and as protection against spirits.1 SEE KOSHER FODEM.

1. Weissler, “Measuring Graves, Laying Wicks,” 61-80.