American Pistol Shooting (2015)

Chapter XX

HINTS ON USING THE SERVICE AUTOMATIC

THE Colt automatic pistol, caliber .45, known in the army as the “Model of 1911” and designated in the catalog of the Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Co. as the “Government Model,” is here referred to as the Service Pistol because it is the official side arm of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. This title is also given to this weapon in the program of the National Rifle and Pistol Matches and frequently in other pistol competitions. Referring to the program for 1928 we find the following: “THE SERVICE PISTOL. Colt automatic pistol, caliber .45, model 1911, as issued except that the front and rear sights may be of commercial manufacture similar in design to the issue sights, though different in dimensions. Not less than four-pound trigger pull.” This paragraph defines the pistol that may be used in matches restricted to the service weapon. There is a further restriction in that the ammunition used in these matches must be: “Full-charge ball cartridge ammunition manufactured for or by the Government and issued by the Ordnance Department for use in the service arms.” In competitions other than those conducted by the War Department the service pistol may, in some cases, be used not as issued and this permits the owner to “doll up” his gun as he sees fit. Alterations that aid in holding may consist of specially made grips to fit the hand of the shooter and any kind of open sights he may prefer. In regard to the latter, however, it is well to stick to the same design as now issued by the manufacturer as these have proven to be very satisfactory.

Since its adoption by our Ordnance Department in 1911 and especially during and since the World War, many thousands of our citizens have used the Service pistol and there are great numbers of these automatics now in their hands in addition to those in use by the Army and Navy. With this in mind it was thought advisable to offer to its many possessors a few hints on the use of this particular gun, which like many of its contemporaries has certain peculiarities of its own and a knowledge of these will work to the advantage of the user.

Let us consider first the safety devices. This particular automatic is equipped with four means of preventing accidental discharges. They are: The half-cock notch, the safety lock, the grip safety and the disconnector.

The half-cock notch when engaged with the sear prevents the pistol being fired even though the trigger be firmly squeezed. It also serves the purpose of catching the hammer should the latter slip while being cocked. It should be frequently tested when the gun is empty and if the half-cock fails to function the defective parts should be replaced.

The safety lock will, if in proper order, prevent the hammer from falling when cocked and locked. To test this device the hammer should be cocked, the safety lock engaged, the grip safety pressed down and the trigger firmly squeezed. If the hammer is released the safety lock is not functioning properly and should be released or repaired.

The disconnector is for the purpose of preventing the release of the hammer until the slide and barrel are safely locked in the forward position, and also prevents one squeeze of the trigger firing more than one shot. To test the disconnector draw the slide to the rear about a quarter of an inch, press the trigger firmly to the rear at the same time letting go of the slide. The hammer should not fall. Now release the pressure on the trigger, squeeze again and the hammer should fall. A further test of the disconnector is to draw the slide fully to the rear and engage the slide stop. Then press the trigger, at the same time releasing the slide. The hammer should remain cocked. On releasing the trigger and squeezing it again the hammer should fall. Were it not for the disconnector the pistol would become an automatic in the strict sense of the word.

The grip safety prevents the pistol from being fired until it has been depressed. This occurs without conscious effort when the butt is gripped in a normal manner by the shooting hand. In testing this safety the pistol should be cocked and the trigger pressed without depressing the grip safety. The device is defective if the hammer falls.

In spite of its safety devices, this pistol is not foolproof and great care should be taken in its use at all times. There are a few rules almost universally found on well regulated ranges which it is well to keep in mind. They are: (a) Do not load a pistol until on the firing line ready to fire. (b) Do not snap a pistol behind the firing line, (c) Unload your pistol before leaving the line. (d) Keep the slide of your automatic drawn back except when ready to fire. (e) Always keep the muzzle of a pistol pointing in a safe direction.

An automatic is different from a revolver in that the cartridges it contains are concealed. For this reason the first step in an inspection of a pistol should be to remove the magazine and then draw back the slide. This will extract a cartridge in the barrel and will prevent another from being fed into the chamber when the slide is released. The service automatic may be carried loaded with a full magazine and an additional cartridge in the chamber. It is perfectly safe to carry this pistol so charged with the hammer down, and is safer than to carry the gun with a cartridge in the chamber and the hammer cocked and locked. An inspection of the pistol will show that the firing pin is shorter than the breech block in which it operates and that when its rear end is flush with the firing pin stop, as it would be when the hammer is down, the point cannot project or rest on the primer of the cartridge. The firing pin base projects to the rear when the hammer is cocked and is held there by a coil spring so that it is necessary for the hammer to hit it a sharp blow in order to drive the point against the primer.

During a field inspection of the 107th Co. C.A.C. in 1914 a lieutenant approached the Captain with his automatic in hand and remarked that he did not seem to be able to make the safety function. The captain explained that the gun must be cocked before the safety could be engaged. He cocked the pistol by drawing the slide to the rear and then engaged the safety. After showing this to the lieutenant he shoved the safety off and pressed the trigger. An explosion followed and a small boy some distance away was hit in the eye with the .45 bullet from the pistol.

This accident illustrates what may happen when safety precautions are violated, especially those fundamental rules which are so simple and yet so vital to the safe use of firearms. A gun should be kept loaded only when necessity dictates such a course. Every gun we handle should be considered as loaded and we should make it a paramount rule never to manipulate one until we have assured ourselves by personal inspection that it is empty or until we have unloaded it. As an added precaution we should always develop the habit of elevating the muzzle well before snapping a hammer out-of-doors. Special care should be taken when snapping practice is held and I have personal knowledge of two cases of careless men shooting through the walls of their rooms when snapping at targets with pistols they thought they had unloaded.

The chance of the hammer being drawn to the rear and then falling on the firing pin so as to discharge the piece is very small and the danger much less than there is when the gun is carried cocked and locked. It is an easy matter to shove the safety off by the pressure of the clothing or of the holster while carrying the gun or drawing it in a hurry. To lower the hammer with a cartridge in the chamber hold the pistol in the right hand, place the right thumb on the hammer spur and press it back until the grip safety is forced forward. Then while holding the hammer securely, press the trigger so as to prevent the sear from entering the hammer notches, and lower the hammer slowly.

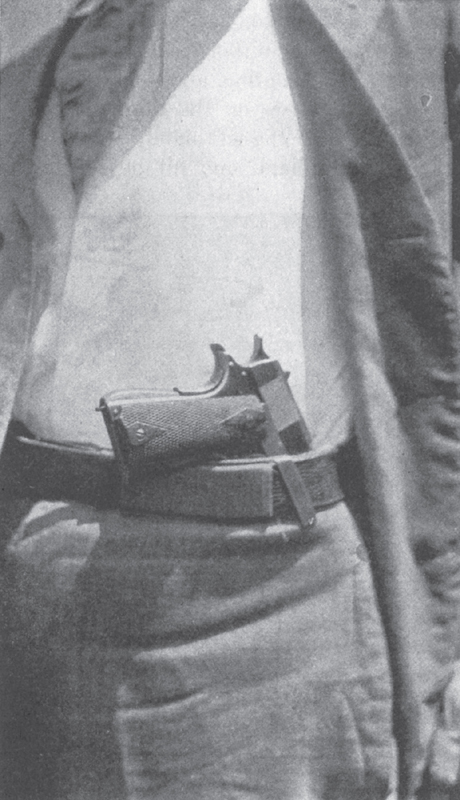

A good way to “pack” the Service automatic. This device was made for the author by a former Deputy U. S. Marshal of Oklahoma

A few years ago the author used this pistol quite extensively for aerial shooting and found that by using an open holster tied low on the thigh he could toss a target in the air with the left hand, draw and cock the gun with the right hand and hit objects as small as French pennies. Many hundreds of shots were fired in this manner without a single accidental discharge and it is safer than to cock and lock the gun before drawing. If the gun is cocked and locked there is always danger of the hand closing on the grip safety and the gun firing as it is drawn, whereas by cocking as the pistol is drawn the hand will not press the grip safety until the muzzle is clear of the holster.

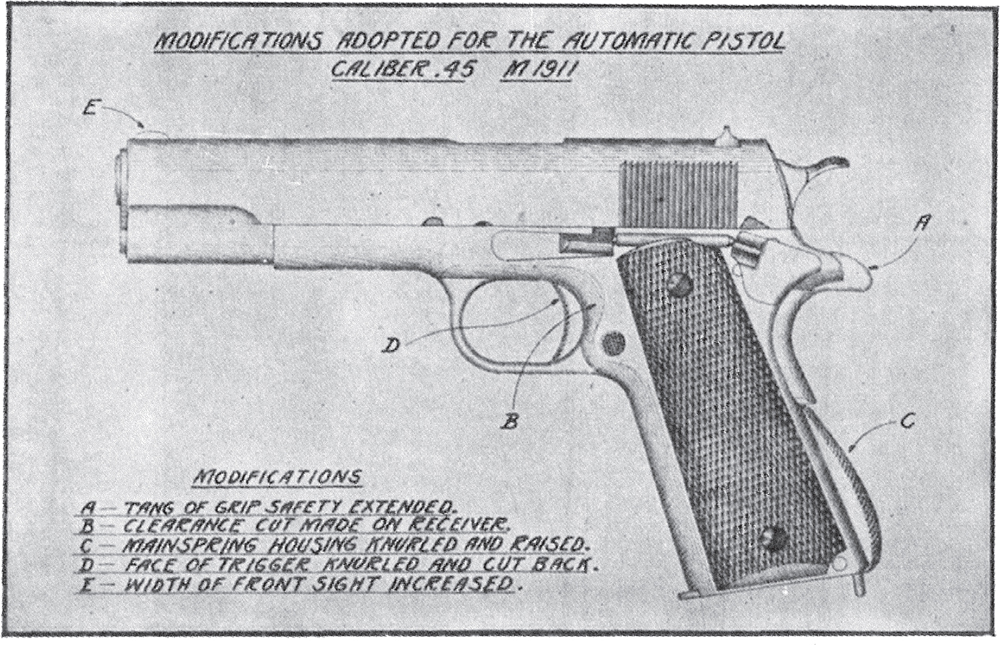

There are now two models of the service pistol in the hands of the Army and Navy and scattered throughout the country. They may be referred to as the old model and the improved model. Actually they are one and the same weapon except for the substitution of certain parts that have been improved in design and consequently have changed the outline of the old model slightly. A few years’ experience with the first model had convinced many users that for the average man this pistol was too much of a handful; that due to the angle between the barrel and the grip the muzzle pointed slightly downward when held in the normal firing position; that the long hammer spur and short grip safety generally pinched a shooter’s hand, if his hand was at all fleshy and the gun was held with the proper high grip. In addition to these characteristics it was found difficult for a small hand with a short index finger to reach the trigger so as to squeeze it straight to the rear in firing.

On the improved model the trigger reach has been shortened by cutting away both sides of the receiver just in rear of the trigger face and by shortening the trigger itself. The face of the latter has also been checked so as to present a rough surface for the trigger finger to press in firing. The tendency to point low has been remedied by enlarging the main spring housing so that it is now raised or arched on the rear face. When the butt is gripped this projection causes the muzzle to be raised more than it was with the old style housing. As the arched housing is now checked it aids one in holding the pistol with the same grip for each shot. A grip safety with a longer spur has replaced the old one so there is much less chance for the hand to be injured between the hammer and safety spurs when the slide and hammer are forced back by the regular operations of the automatic mechanism. In the case of a very fleshy hand, however, it is well to get a hammer with a shorter hammer spur or file off a little of the underside of the spur of the hammer issued on the gun. In general, the gun was improved by these changes and its handling and firing was made much simpler for the man with a small hand. A study of a few other characteristics of the pistol, especially of the older model, will aid one in improving his shooting with this popular weapon.

The service automatic should be gripped more firmly than a revolver for the reason that failure to properly seat it in the hand may cause one to ease up on the grip safety in the excitement of a rapid fire match to the extent of putting the gun on “safe” so that it will not fire. This is demoralizing but has been done by men accustomed to maintaining a very light grip on target revolvers or pistols.

If one expects to use the older model in competition or qualification firing he should make a careful analysis of his technique in so far as the shooting hand and arm are concerned. With the arm fully extended and the gun held naturally in the firing position the muzzle will have a tendency to incline downward and the effort to raise it will put a slight strain on the wrist which is generally increased materially by the shock of recoil during firing. This makes the operation of holding more difficult than it would be were it not necessary to bend the wrist and raise the hand while aiming and firing. This little detail is not appreciated by many users of this pistol and while all are not affected by it because of individual peculiarities of technique it does affect many and retards their progress. To illustrate my point I will again take the liberty of using an incident of personal experience. When the .45 automatic was first issued as the service pistol I found great difficulty in consistently making forty out of a possible fifty points on the Army “L” target at fifty yards slow fire, although I had been shooting the revolver and target pistol successfully a long time. This was quite embarrassing and even exasperating and much effort and time was spent on overcoming the difficulty, with apparently little success. One day after an especially discouraging practice I mentioned my troubles to my battery commander who, while not an excellent shot, had some very definite ideas about the game and shot very well. He had me demonstrate just how I fired and the minute I extended my arm fully he criticized me for so doing and all arguments for this manner of shooting went for naught with him although he approved of the rest of my technique.

The next day while practicing it occurred to me to try out the old captain’s method. I extended my arm fully as I always had done and then relaxed it slightly so as to have a slight bend at the elbow. To my surprise and pleasure I found that my scores jumped up at once and out of seven strings of five shots fired that day I made better than 40 points on every score but one and that was a 39. By bending the arm slightly at the elbow I had relieved the strain on my wrist and from that time until the improvements were made on the pistol I used that method of firing. Since my discovery I have heard a very fine pistol coach advocate the same procedure in shooting with the older issue service pistol. Another point to be studied in connection with gripping this gun is the effect of the automatic operation on the firing hand. This gun is so different in shape and action from a revolver that the reactions set up in the hand muscles are quite astonishing at times. A beginner with this weapon will find that his first score is generally his best one and that after firing a few shots he will begin to flinch and his hand will tremble very noticeably. Even experienced revolver shots find when using this pistol that they develop unsteadiness in holding much quicker than they do when using the six shooter. When we remember that this is among the most powerful hand guns made and that there is normally a strong recoil from the cartridge used, we must expect to get considerable shock during firing. If we fire rapidly the repeated shock of recoil quite naturally causes tremors in the hand which in turn cause unsteadiness in holding. The shock from a revolver comes mainly against the fleshy part of the hand between the thumb and first finger and if firing is continued this part of the hand will become sensitive and may cause flinching. When using the automatic there is of course less recoil felt but the effect of the vibrations of the slide and its adjoining mechanism as it is driven to the rear and then forward again by the counter recoil action is even worse than the effect from the recoil in its tendency to set up tremors in the shooting hand. Let a beginner fire a few scores rapidly with the service pistol and he will soon find his hand quivering from the reactions of the mechanism which has been working back and forth above it. If this condition is properly appreciated the marksman will welcome every opportunity to shoot slowly with this particular gun and to take enough time between strings of rapid fire to prevent his hand from reaching the quivering point or, if it does develop tremors, to rest it long enough to quiet them. In the use of any pistol it is generally considered good practice to extend the thumb along the side of the piece if the conformation of the weapon will permit it. With the service gun there are several reasons why this is advisable. The large butt causes many persons to grip it more on the right side than is correct. This results in greater pressure on that side and a tendency to shoot left caused by the pressure of the hand and of the index finger when squeezing and firing. If this weapon is properly seated in the hand so that the barrel is parallel to the center line of the forearm it can be held more uniformly with the thumb along the side at about the same height as the third joint of the index finger. To secure uniformity of pressure with the thumb try this method: When the pistol has been well seated in the hand with the grip safety pressed in properly let the right thumb fall naturally on top of the second finger and then roll it up until it is parallel to the bottom of the slide and slightly below it. This should be done for each shot fired deliberately and for each string of rapid fire until it becomes natural and one does it unconsciously.

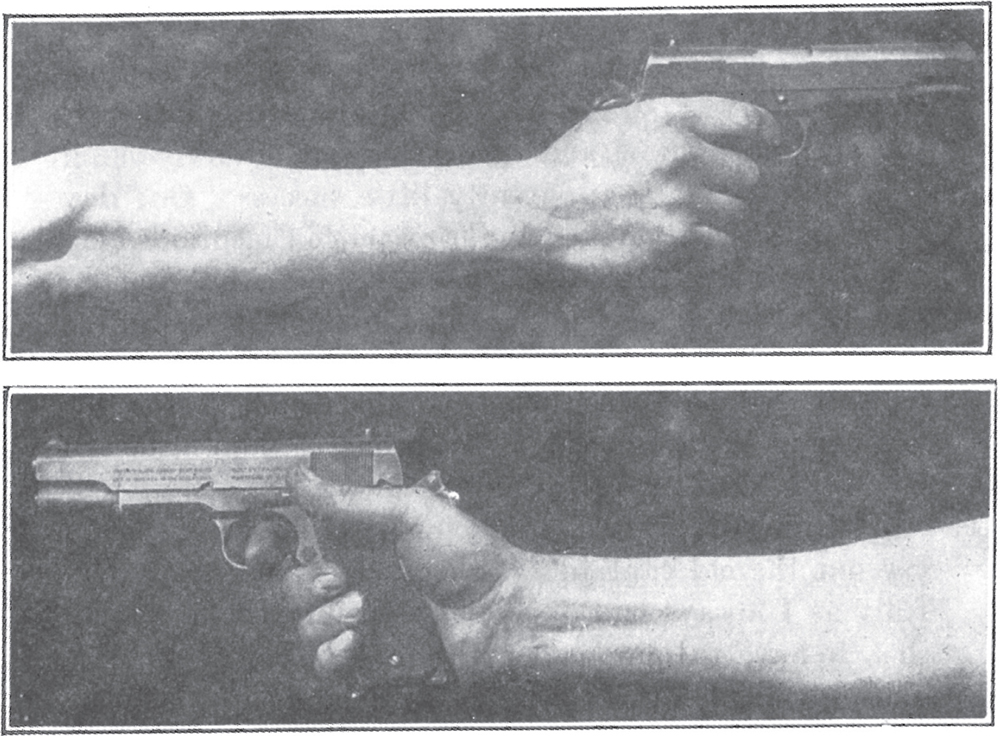

The correct way to grip the service automatic. Note position of the trigger finger, arm and wrist.

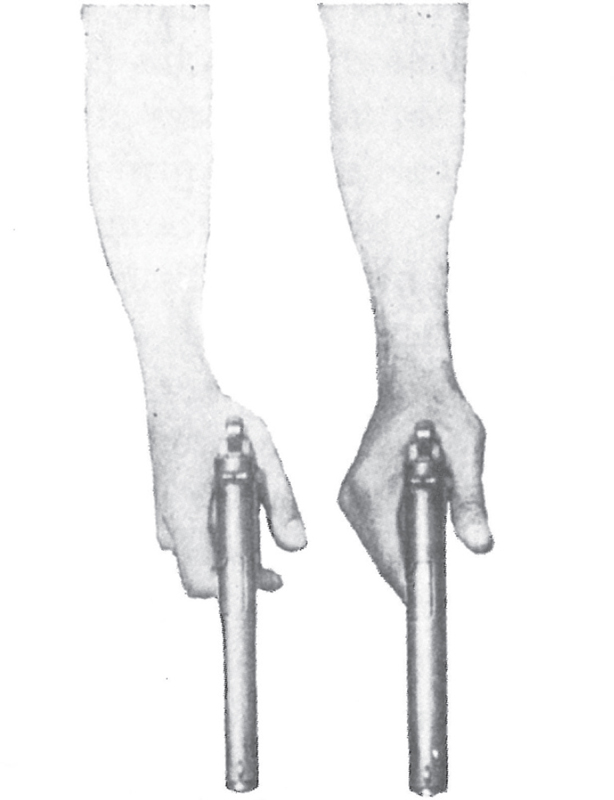

Left—The wrong way to grip the service automatic. Pistol not in prolongation of the arm. Right—The correct way to grip the service automatic.

Due to the fact that the service weapons were turned out in great quantities during the recent war and that the parts were made interchangeable without fitting, there is apt to be more looseness in many assembled pistols than is desirable in a target gun. As a result many of them do not seem to give the accuracy that can be expected of a good gun of this model. The most noticeable defects of this kind are the loose fit between the slide and the receiver and the play between the barrel and the barrel bushing and between the latter and the slide. Too much play between the slide and the receiver can be reduced by removing the slide, laying it on a firm support and tapping it along the lower edge with a small lead or bronze hammer. This must be done carefully by working from rear to front and trying the slide on the receiver frequently. The object should be to take up the looseness without making the parts bind at any points. The play between the barrel bushing, slide, and barrel can be overcome by substituting a thicker bushing if one has access to spare parts.

The kind and condition of the barrel will have more to do with the shooting qualities of the pistol than any other parts. There have been several changes made in the ammunition and the diameter of the barrel in recent years and one should assure himself that he has the latest size barrel and match ammunition, if he expects to get the most out of his pistol. The Colt’s company sells special match barrels which are greatly superior to those issued by the Ordnance Department. Their cost is relatively low and the satisfaction of having one more than pays for its expense.

Occasionally one gets a gun that jams during the extraction and ejection of the empty shells. This may be due to having a recoil spring that is too stiff and it can be improved by cutting off a few of its coils. If a jam occurs during the reloading or feeding of the shells into the chamber it is usually the fault of the magazines which become defective by much use and abuse. When jams occur test the gun first by using a good magazine and then if the trouble continues look for it in the gun itself.

The older service automatics were issued with rear sights with circular tops whereas those of more recent issue have the more satisfactory rectangular rear sight bars. The older front sights were low, thin and quite pointed when seen from the rear. It has now become the practice to mount broad front sights on the service pistols selected for the National Matches and is permissible under the rules. These can be put on the slides of all pistols except certain lots that were made by Springfield Armory. The sights on these Springfield slides were made integral with the slide and cannot be removed and replaced. The disadvantage of the old pointed sights, in addition to the difficulty of aligning them accurately, was the effect of heat waves on their appearance. On very hot sunny days while firing rapid fire, heat waves from the barrel will play across the sight and make it very difficult to see clearly and with a corresponding bad effect on one’s score. The use of the broad front sight largely eliminates this trouble.

The trigger action of the service pistol is different from that of a revolver and should be given special study by persons unaccustomed to its characteristics. The first pressure on the trigger does not affect the hammer but merely takes up “slack” and brings the disconnector against the sear whereas in a revolver any pressure on the trigger affects the hammer. There is no danger of firing the pistol if the slack is properly taken up and the trigger pull is what it should be. With all straight pull weapons the pull seems less than the same amount does on a revolver or pistol that receives an angular pressure. For this reason a heavier pull can be used on this weapon to advantage. The rules for all army competitions require that the trigger pull be not less than four pounds tested with the barrel held vertically. A clean five-pound pull can be used very satisfactorily unless one is accustomed to the very light ones allowed on target pistols. If one attempts to reduce the pull below four pounds he will find that he is unable to use it for any but single shots. The jar caused by the heavy slide springing forward after the previous shot has been fired and the shell ejected, is so great that it will release the sear from the hammer and the latter will follow the slide forward. This may occur with a pull of four pounds although the author has used a pistol for several years with a pull slightly over that amount and it has never failed to function properly in this respect.

There is little doubt that obtaining a suitable trigger pull is among the first problems that a marksman meets when he begins using the average service gun. All pistols issued to the services have unusually heavy pulls unless they have been specially selected for the National Matches or other competitions and even then they are apt to be heavier than an experienced shot desires. This is a wise precaution for it is dangerous to issue guns with light pulls to recruits or novices, especially if they are mounted and expect to fire from the saddle. For a while the minimum trigger pull allowed in the army competitions was 6 pounds, but this has now been reduced. It would not be so bad if the heavy pulls were smooth and clean so that when the sear released the hammer it did so with a clean break. This is usually the exception in issue guns, for in addition to being heavy the trigger action is rough, creepy and uncertain. There is also frequently found on service pistols what is known as a spongy trigger pull which is almost as bad as creep. It is due to the sear trying to raise the hammer by a camming effect before it can release itself from the notch.

When the trigger is pressed it in turn presses against the lower end of the disconnector and the center prong of the sear spur. The disconnector then presses the lowest end of the sear and this pressure tends to release the point or nose from the hammer notch. From this long operation it is easy to account for possible creep. The first movement of the trigger to the rear presses back the sear spring until the disconnector is against the sear and any additional pressure then acts on the hammer. Before attempting to lighten the trigger pull an effort should be made to eliminate all the creep caused by rough contacts. This is done by polishing all bearing surfaces and especially those of the sear nose and the hammer notch. After this has been done if there is still creep present and the weight is too great other steps must be taken. Before encouraging anyone to attempt to reduce the pull on the service automatic let me state that I believe that to make this adjustment on this particular gun is the easiest and yet the hardest trigger adjusting job a pistol man can undertake. It is easy because it can be done quickly if one knows the knack or tricks of doing the work. On the contrary to do this job well requires a careful study of the problem and infinite care and patience on the part of an amateur. For eight years to my knowledge the Colt company has sent to the National Matches, one of their factory experts, J. H. FitzGerald, whose duty among others has been to gratuitously assist pistol shooters in every way possible. “Fitz,” his table and large umbrella have become a familiar sight back of the pistol firing line. His main occupation has been to adjust pistols, and the ease and skill with which he does this is quite marvelous. As there are hundreds of service automatics present to one revolver he naturally gets more of the former to adjust. It must not be assumed from this that the Model 1911 is always in need of adjustment, for if one buys a new pistol of this model from the factory he will find it is all that could be desired in the way of accuracy, adjustment and workmanship and will not need repairs for years if properly cared for. When we remember that most of these pistols in use today were made under pressure of a great national emergency when the best materials and labor were not available and the usual high standards of workmanship could not possibly be maintained we can understand why there is great need of adjustments for these guns if they are to be required to give satisfaction in target competitions. For four years I have watched “Fitz” adjust the pistols of the team with which I fired, to say nothing of the hours I have spent observing him in action at Camp Perry. From him I have absorbed sufficient knowledge and skill to in turn assist others.

The methods used by FitzGerald on the firing line are necessarily emergency measures for he has hundreds of jobs given him each day and he has to work fast to accomplish the most good. A favorite expedient of his in reducing the trigger pull or the creep therein is to burnish the sear and the notch by pressing hard on the hammer at the same time he presses the trigger. If this does not do the business he quickly dismounts the gun, inspects the parts and either substitutes others or with a few strokes of a quick-cutting, smooth file touches up those that need it. His thorough knowledge of the weapon and his long experience in this particular work enables him to accomplish wonders in a minimum of time, and incidentally, these methods are not to be recommended for the amateur. Emergency adjustments usually answer for the emergency but do not as a rule hold up very long, and it is much better to take more time and do the work slowly, carefully and thoroughly.

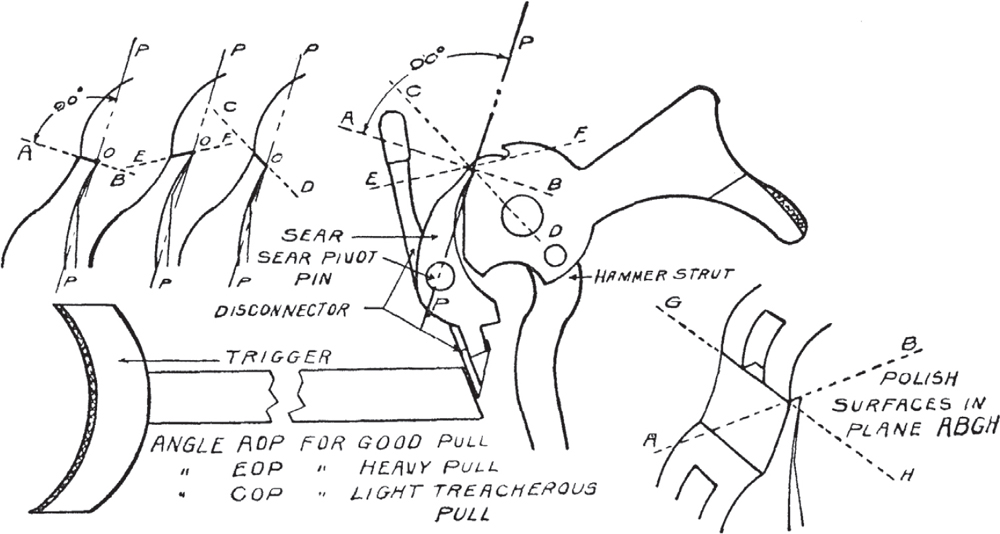

The following is offered as a safe procedure in working on a service pistol. Study the sketch showing the hammer, sear, disconnector and trigger. Pay particular attention to the way the sear fits the notch, and the angle the two bearing surfaces make with relation to the line from the center of the sear pivot to the innermost point of the sear. In other words, determine first what you want to do without question or in the words of Davy Crockett, “Be sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

Note that one of the unusual things about the hammer is that it is split so that the sear rests in two separate notches, one on either side of the cut-out center. You have actually two notches to work on and one sear, which is different from other arms. If the angle of the notch seems to be correct try rubbing down the sear nose first until it fits the bearing surface of the notch. Do this on a hard, smooth surface stone. For years I have used various shapes of Arkansas stones which are not always easy to obtain but will give the greatest satisfaction of any of which I know. A good hard razor hone can be used. The Arkansas stone is white, or nearly so, when new and if it has sharp corners or a knife edge shape on one side it should be carefully protected, for it will chip easily. It is not necessary to put oil on the stone if one wants a polishing rather than a cutting surface. Another necessary piece of equipment is a magnifying glass to enable one to see clearly the shape of the small surfaces and angles with which he is working. For this purpose I finally adopted a jeweler’s glass with a 3½ inch focus which cost 75 cents. Examine the sides of the hammer and sear around the notches and point respectively and remove any burrs found by laying the parts flat on the stone and polishing them. In polishing the sear nose be careful to keep this small surface flat on the stone to avoid taking off more on the sides and leaving a convex effect in the center. After getting the sear polished satisfactorily try the action of the trigger by assembling it and squeezing it very carefully, at the same time aiming and holding carefully on a small target. If it is still too heavy it will be necessary to work on the notch and sear and grind them off very slowly, trying the action frequently. A trigger weight with a convenient hook to slip on the trigger as the pistol is held vertically is the best means of testing the work. The weight including the hook should be half a pound heavier than the pull desired. This is where the operation becomes tedious and one is inclined to finish the job with a file. If one has an unusually deep notch this procedure may be necessary, but that can be determined by study beforehand. When working on the pistols of soldiers I have frequently resorted to this method and have several small smooth files of different shapes. The one I prefer is a jeweler’s square taper file about an eighth of an inch on the side. It is a pillar file and marked “4 Made in Switzerland.” It has three cutting surfaces and one smooth or blank face. A few strokes with this file and a little polishing with the stone is all that is frequently needed. One of the dangers of working with service guns is that the case hardening on the hammer and sear is frequently very thin and once this is penetrated the metal is so soft that a good adjustment will not hold unless one can have the parts again hardened.

A little experience in adjusting triggers will convince one that when he has a reasonably good trigger he should leave well enough alone or send the gun to the factory and have the work performed there. It is realized that there are times when it is not convenient to have a factory job done or even to secure the services of a good gunsmith and it is then that knowledge and skill in this work is valuable. The greatest drawback to sending one’s gun away is the time it takes to get it back and the loss of practice in the meantime. A real pistol man should be able to make these adjustments and after a little perseverance and patience he can do it quite satisfactorily, but like the other details of the game it requires time and study to master.

A remodeled Service automatic that became an excellent target pistol.

To sum up the instructions given here on adjusting triggers and to clear up any ambiguous statements the following steps are recommended:

1. Polish the bearing surfaces of the hammer notch and the sear nose and remove burrs from the edges.

2. To reduce the pull, grind down the bearing surfaces until they are flat and so that they make a right angle with the line from the center of the sear pivot to the inside point of the sear nose, when the hammer is cocked. See the lines A—B and P—P in the sketch.

3. Polish these surfaces carefully and round off slightly the inside edge of the sear nose.

4. If the pull is still too heavy, bevel very slightly the bearing surfaces until they make an angle slightly less than 90 degrees with the line P—P. If this is overdone the sear will not hold safely and accidental discharges may result.

5. Test your work frequently by assembling the action and trying the pull with a trigger weight.