50 Famous Firearms You've Got to Own: Rick Hacker's Bucket List of Guns (2015)

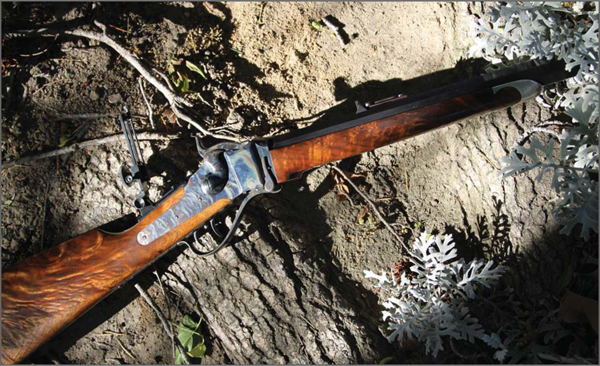

1874 SHARPS

Certain rifles transcend their time, and one of the most enduring is the 1874 Sharps. Known by monikers such as “Old Reliable,” “Buffler Rifle,” and “The Big 50” (referring to its popular .50-100 chambering), it was praised by such nineteenth century luminaries as John C. Fremont, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Theodore Roosevelt. Quick to reload and having both a solid, drop-block action and superbly rifled barrel, the 1874 Sharps was not only the choice for serious big-game hunters, it played a major role in disseminating the West’s vast buffalo herds—a dubious distinction, to be sure.

The evolution of events leading up to the single-shot that tamed the west began on September 12, 1848, when a young inventor named Christian Sharps patented a breech-loading rifle that utilized a lever-operated drop-down breechblock. In the era of the muzzleloader, where one had to stand in order to ram a charge down the barrel, the Sharps had an enticing military appeal, as it enabled soldiers to reload without exposing themselves to enemy fire. They merely opened the lever, which exposed the breech, put in a lead bullet, and then seated it against the rifling with a powder charge. Closing the breech and placing a percussion cap on the nipple readied the gun for firing. Unfortunately, America was not at war in 1848, and, consequently, the government had little interest in the unique breechloader. This lack of interest and, subsequently, a lack of funds, forced Sharps to subcontract his first 700 rifles; they weren’t even stamped with his name.

A few years later, Sharps convinced the firm of Robbins & Lawrence to manufacture his Improved Model of 1851. Thus, the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company was formed in Hartford, Connecticut. Shortly thereafter, a series of personality clashes caused Christian Sharps to leave the firm. Although Sharps continued to receive royalties on his rifles, it was Richard S. Lawrence, the company’s armorer, who continued to make improvements on the original patent and kept the rifle in production.

This replica “Quigley” rifle is made by Pedersoli. The rifles used in the motion picture (there were three of them) were made by Shiloh Sharps.

This Dixie Gun Works “Quigley” long-range rifle by Pedersoli is shown with a limited edition silver .45-110 commemorative bullet offered by the National Rifle Association and embossed with actor Tom Selleck’s signature.

Subsequent versions, including the slant-breech Model of 1852 and the more efficient vertical breechblock of the New Model 1859, eventually brought the Sharps rifle to the attention of the U.S. government. But it was The War Between The States that finally brought orders and much needed Yankee dollars to the struggling Sharps company. During The Great Rebellion, the Sharps became a favored weapon for snipers, who found it convenient to reload while concealed in treetop perches. The rifle’s reputation also resulted in Colonel Berden’s 2nd Regiment of Sharpshooters threatening mutiny when they were shipped 2,000 of Colt’s revolving rifles, instead of the Sharps rifles they had been promised—they quickly got their Sharps. By the end of hostilities in 1865, a total of 80,512 carbines and 9,141 full-stocked military rifles had been shipped to Union troops. The Model of 1865 was the last percussion Sharps made, with 5,000 carbines manufactured shortly after the war.

With such sizable orders, a great reputation, and thousands of ex-Rebels and Yanks heading west and in need of a reliable rifle, one would think that the ill-fated fortunes of the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company were over. But, in 1874, right on the eve of America’s great frontier expansion, Christian Sharps and Richard Lawrence died within months of each other. With the passing of the rifle’s inventor and its chief proponent, the company shuttered its doors. Indeed, the Model 1874 might never have been a reality had it not been for a group of investors, who reorganized the firm as the Sharps Rifle Company.

The rifle that launched this second venture was the Model 1874, an updated version of the older percussion models and designed for the new era of the self-contained metallic cartridge. While lever-actions of the day such as the Henry and Winchester’s Models 1866 and 1873 were boasting repeat-fire capabilities, their slim and relatively weak actions simply could not contain nor sustain heavy loads—certainly not cartridges packing enough power to anchor tenacious western big game such as grizzlies and elk.

The new 1874 Sharps had no such problems. It was a handsome, solid, and hefty rifle, with an average weight of 12 pounds, although some specimens—most notably those with thick, special order barrels—tipped the scales at 25 pounds or more. The rifle’s jam-resistent action was proven and strong; in fact, many lock parts were carryovers from the percussion guns, which had already established their reputation in combat.

The heavy weight of many Sharps hunting rifles necessitates the use of shooting sticks.

The author replicates the bison hunter’s technique of keeping an extra shell between his fingers for a fast follow-up shot.

Not only was the 1874 accurate and rugged, it was easy to maintain. With a single, removable steel pin, the entire breechblock and hinged lever could be dropped out of the frame for cleaning. The machine-rifled barrels of the new 1874 had a 1:20 twist, with shallow lands and grooves. Barrel lengths ran from 211⁄2 inches to 36 inches and could be had in round, octagon, or half-round/half-octagon configurations. The earliest guns featured a distinctive “Hartford collar,” a milled ring around the base of the barrel where it joined the receiver. When the company moved to Bridgeport, in 1876, this decorative feature was dropped. In April of that same year, the rifle’s nickname, “Old Reliable,” began being stamped on the barrels.

A Sharps 1874 Sporting Rifle, shown with an original paper-patched .45-70 cartridge.

The original breech stamping on an 1874 Sporting Rifle.

Stocks were plain, oil-finished American black walnut, although fancier wood could be ordered. The earliest 1874 models featured pewter-tipped Hartford forearms. After 1877, this attractive feature was replaced with a schnabel tip, although both the earlier Hartford collar and pewter fore-end could be special ordered for an extra charge. Receivers were case hardened, with all other metal parts being blued. Single and double-set triggers were offered, and the variety of front, rear, tang, and telescopic sights was enough to satisfy the demands of the most discriminating customers.

Indeed, the numerous models of the 1874 Sharps were as varied as the shooters who ordered them. Cataloged versions included Sporting Rifles, Lightweight Sporting Rifles, Creedmore and Schuetzen target rifles, Business Rifles, a full-stocked Military Rifle, a bare bones Hunter’s Rifle, and a saddle carbine, among others. Of course, a plethora of options, including straight or pistol grip stocks, special barrel lengths and weights, and engraving could be special ordered—and often were. In short, the 1874 Sharps was a very labor intensive, custom-made rifle, facets that were reflected in the price. While Winchester’s breechloading repeaters were selling for as little as $10, a basic single-shot Sharps was priced at $33. Nonetheless, with specialized cartridges like the .40-90, .44-77 bottleneck, .45-100, and .50-100, the 1874 Sharps soon became the big-game rifle among savvy frontiersmen and serious hunters.

Vernier tang sights are a popular feature on Sharps rifles, whether replicas or originals.

This early Shiloh Sharps is stamped with the original Farmington, New York, address that is sought after by some collectors.

The Sharps proved itself on target ranges as well. During one memorable 1,000-yard match, in 1877 at Creedmoor, Americans firing long-range Sharps rifles soundly defeated a British team. But it was in the hands of buffalo hunters that the 1874 Sharps lived up to its “Old Reliable” reputation. Most of these “buffalo runners” carried one or more Sharps rifles, firing volley after volley at the big, shaggy beasts, at ranges that often exceeded 400 yards, and switching guns when the barrels became too hot to handle. Another notable long-range event occurred in 1874, during the Battle of Adobe Walls, when a young hunter named Billy Dixon borrowed a “Big .50” Sharps from none other than Bat Masterson and toppled a Kiowa chief at what was later confirmed to be 1,538 yards (7⁄8-mile).

In spite of these and other success stories, economic woes continued to plague the Sharps Rifle Company. With the unexpected cancellation of a large British order, the firm was finally forced to close its doors; the last gun was shipped in 1881. Although it was an internationally renowned rifle whose inventor never got rich, the 1874 Sharps had amassed enough glory in seven years to create a legacy that continues today.

Originals are the centerpiece of many a collection. Fortunately, there are now excellent replicas made by Italian firms such as Pedersoli and Chiappa. In addition, firms such as C. Sharps Arms and Shiloh Sharps, both located in Big Timber, Montana, are emulating the original Sharps Rifle Company by handcrafting 100-percent custom-built rifles for the discriminating sportsman. I own more than one of these heavy hitters, and, with them, have taken everything from a Rowland Ward recordbook impala in Africa, to a 2,000-pound bull bison on the plains on Montana. No wonder this nineteenth century single-shot is on my bucket list.