The Pursuit of Perfect: How to Stop Chasing Perfection and Start Living a Richer, Happier Life - Tal Ben-Shahar (2009)

Part I. The THEORY

Chapter 4. Accepting Reality

Two and two do make four. Nature doesn’t ask your advice. She isn’t interested in your preferences or whether or not you approve of her laws. You must accept nature as she is with all the consequences that that implies.

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky

This chapter is about the philosophy of perfectionism and more specifically about metaphysics, the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of reality. Metaphysics is important to the study of perfectionism because underlying many of the Perfectionist’s characteristics is the rejection of reality—whether it is in the form of failure, painful emotions, or success.

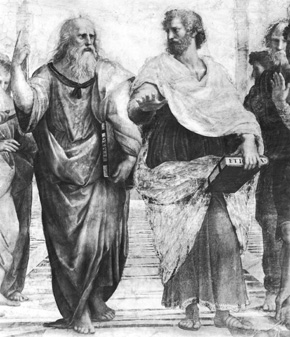

We can trace perfectionism’s intellectual roots to Plato, the father of Western philosophy. Aristotle, Plato’s student, broke away from his teacher and preached realism and thus became the de facto father of optimalism. The distinction between Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy is captured in Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, in which Plato points to the sky and Aristotle points to the ground. While tomes have been written about their different approaches to philosophy, I would like to focus on their

Plato, the Perfectionist (left), and Aristotle, the Optimalist

different approaches to psychology, specifically as it relates to perfectionism. Plato the Perfectionist is pointing to the dwelling place of the gods, to the supernatural, to the perfect. Aristotle the Optimalist is pointing to this world, to the natural, to the real.

According to Plato, the primary building blocks of reality are forms—perfect archetypes, ideal models—from which particular objects arise. Plato argues that although we may think we live in the real world, we do not; we are like cave dwellers who are facing away from the entrance to the cave, bound and unable to turn around or leave. The real world, the world of perfect forms, exists outside the cave, where a fire burns and projects the shadows of the forms onto the wall of the cave for us to see. In modern-day terms, we spend our lives locked up in a movie theater, so involved and absorbed in the drama on the big screen that we are oblivious to our actual predicament. Each object that we perceive in our illusory world is a projection of the perfect form that exists in the real world: the horses that we see are mere imperfect projections of the perfect horse, the people that we see around us are not real but imperfect imitations of the perfect human. According to Plato, it is possible to know reality, but only through philosophical contemplation that is not affected by our experiences, our emotions, or what our senses tell us—mistakenly, in his view—about the world.

Unlike Plato, Aristotle’s view of reality is not at odds with our experience of the world. While for Plato there are two worlds (the perfect world of forms and the imperfect world we perceive), for Aristotle there is only one world, one reality, which is the world we perceive through our senses. Sense perceptions provide us with experiences, from which we generate forms either as mental images or as words. The mental picture that we have of a horse is derived from our direct or indirect experience of horses. We know what the word human means because of our direct or indirect experience of humans.

For Plato, forms are primary, in the sense that the world around us is derived from them. Because we can only know these forms through pure reason that is independent of our experience, thinking precedes experience. For Aristotle, forms are secondary, in the sense that they are derived from the world around us. Because we can only know these forms based on our experience, experience precedes thinking.

The psychological implications of these two very different philosophies are significant. For Plato, our experiences are mere projections of what he considers reality, and they stand in the way of knowledge of the truth (the world of forms). Consequently, if our experience contradicts an idea we hold, we should reject the experience. For example, our experience—which includes our observation of the experiences of others—might teach us that failure is necessary for success. But if our Platonic idea of the path to success—success in its perfect form—is of a straight and unimpeded journey, then we should reject our experience and accept our idea. This is the way Perfectionists form their worldview.

For Aristotle, our experience of the world is fundamental for knowing the truth. Therefore, if experience contradicts a certain idea that we hold, we should reject the idea and not the experience. For example, if we see that the only path to success leads through repeated trial and error, then we should reject the idea—whether it is our own or other people’s—that the path to success can be free of failure. This is the way Optimalists form their worldview.

To say “I refuse to feel sad” or “I will not accept failure” is Platonic—an attempt to reject reality by giving precedence to the idea of how we believe we ought to be. To say “I do not like feeling sad, but I accept this emotion as natural” or “I dislike failure, but I accept the fact that some failure is inevitable” is Aristotelian—it acknowledges the primacy of the reality that we experience and observe. Diane Ackerman writes about Plato’s impact on perfectionism, “When Plato wrote that everything on earth has its ideal version in heaven, many took what he said literally. But for me the importance of Plato’s ideal forms lies not in their truth but in our desire for the flawless.” The desire for the flawless condemns us to perpetual displeasure with who we are: “Even the most comely of us feel like eternally ugly ducklings who yearn to be transformed into swans.”1

![]()

What is the appeal of a Platonic philosophy? Why has it had so much influence over the course of history? What is the appeal of Aristotle’s ideas? Why have they been so influential?

The Constrained Vision

Work by Thomas Sowell of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University can help us understand the significance of the Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives. Sowell’s work deals mainly with political science, but it has implications for psychology in general and specifically for our understanding of perfectionism and optimalism.

Sowell points out that all political conflicts can essentially be boiled down to a disagreement between two different views of human nature: the constrained view and the unconstrained view.2 Those who lean toward the constrained view believe that human nature is immutable: it does not change, and we should not waste time and effort trying to modify it. Fashions, technology, landscape, and culture may all change, but human nature is a constant. Human flaws are inevitable, and the best we can do is to accept our nature, its constraints, its imperfectability—and then optimalize the outcome based on what we have. Because we cannot change our nature, we must create social institutions that will channel our given nature in the right directions.

In contrast, those who hold the unconstrained view believe that human nature can be changed and improved: solutions exist to every problem, and we should not compromise or be resigned to our imperfections. The role of social institutions is to create systems that will modify our species in the right direction. We therefore sometimes need to work against our nature, to conquer it. Sowell writes, “In the unconstrained vision, human nature is itself a variable and in fact a central variable to be changed.”

On the whole, people on both sides have good intentions, but due to a fundamentally different understanding of human nature, they prescribe very different political systems. Those who believe in humanity’s constrained nature are typically free-market capitalists, while those who hold the unconstrained view tend to support various forms of utopianism, including Communism.

The capitalist system attempts to channel the individual’s self-interest for the common good, and it makes no serious attempt to change people’s self-interest or natures. Adam Smith, the Scottish philosopher whose constrained vision gave birth to the free-market economy, wrote, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.”

On the other side of the philosophical divide we have Communism, which was inspired by the unconstrained vision of humanity. Communism challenged human nature and sought not to channel it but to change it. In the “New Soviet Person” self-interest would give way to altruism; people would go against their basic instincts, rise above their natural inclinations; human nature would be replaced with superhuman nature. Leon Trotsky, among the leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution, wrote in the early 1920s about the importance of changing man’s nature:

The human species, the coagulated Homo sapiens, will once more enter into a state of radical transformation, and, in his own hands, will become an object of the most complicated methods of artificial selection and psycho-physical training… . Man will make it his purpose to master his own feelings, to raise his instincts to the heights of consciousness, to make them transparent, to extend the wires of his will into hidden recesses, and thereby to raise himself to a new plane, to create a higher social biologic type, or, if you please, a superman.

These are inspiring words, and they help to explain how so many people could be seduced by the Communist vision of a better human being and an ideal society. But these ideas and ideals are detached and unrealistic, and they led to the death, murder, and suffering of untold millions of people around the world.

Psychologist Steven Pinker has challenged “the modern denial of human nature,” the belief that we are born a blank slate and that everything that we are we acquire from our experiences, from our culture, and from our environment. One of the appeals of the blank slate hypothesis is that our nature can be molded—in other words, made perfect:

The belief in perfectibility, despite its rosy and uplifting connotation, has a number of dark sides. One of them is the invitation to totalitarian social engineering. Dictators are apt to think: “If people are blank slates, then we damn well better control what gets written on those slates, instead of leaving it up to chance.” Some of the worst autocrats of the 20th century explicitly avowed a belief in the Blank Slate. Mao Tse-tung, for example, had a famous saying, “It is on a blank page that the most beautiful poems are written.” The Khmer Rouge had a slogan, “Only the newborn baby is spotless.”3

Adam Smith and other proponents of capitalism were Aristotelian: they believed that there is such a thing as human nature and that government must be constructed around that reality. The Communists were Platonic. They conceived of the ideal form of society, and their objective was to shape the imperfect outside world so that it would reflect the ideal form. Like sculptors, they attempted to carve away the parts of human nature that did not fit the utopian ideal. Plato and those who believe in an unconstrained humanity have a view of what our nature ought to be and strive for this perfection, thus rejecting our actual nature; Aristotle and those who believe in a constrained humanity accept human nature as it is and then attempt to make the best, the optimal, use of it.

Clearly, the vision of human nature to which we subscribe has political and societal implications. But its implications on the individual level are no less significant. A Perfectionist subscribes, implicitly or explicitly, to the unconstrained vision of human nature. The refusal to accept painful emotions is a rejection of our nature; it is the belief that human nature can be modified, improved, perfected. While the utopian ideal of Communism was to eradicate the instinct toward self-interest and replace it with altruism, the utopian ideal of the Perfectionist is to eradicate painful emotions, to do away with failure, and to attain unrealistic levels of success.

The Optimalist recognizes and accepts that human nature has certain constraints. We have instincts, inclinations, a nature that some would argue is God-given and others would say has evolved over millions of years. Either way, that nature is not about to change—certainly not in the span of one lifetime—and to make the most of our nature, we need to accept it for what it is. Taking the constraints of reality into consideration, the Optimalist then works toward creating not the perfect life but the best possible one.

The unconstrained view is as detrimental on the individual level as it is on the political, societal one. While optimalism is most certainly not a panacea for all our psychological ills, the quality of life that an Optimalist enjoys is far better than the Perfectionist’s. The notion that we can enjoy unlimited success or live without emotional pain and failure may be an inspiring ideal, but it is not a principle by which to lead one’s life, since in the long run it leads to dissatisfaction and unhappiness.

The Law of Identity

Perhaps Aristotle’s most important contribution to philosophy and psychology—part of the constrained worldview that he endorsed—is the law of noncontradiction: something cannot be not itself. For example, a “horse” cannot be its contradiction, a “not horse”; a “person” is not a “not person.” According to Aristotle, the law of noncontradiction is axiomatic and self-evident and does not require proof: “it is impossible that the same thing can at the same time both belong and not belong to the same object and in the same respect.”

From Aristotle’s law of noncontradiction follows logically the law of identity, which states that something is itself: a person is a person, an emotion is an emotion, a cat is a cat, a number is a number. The law of identity is the foundation of logic and mathematics and, by extension, of a coherent and meaningful philosophy. Without the law of noncontradiction or the law of identity, says Aristotle, it would be “absolutely impossible to have proof of anything: the process would continue indefinitely, and the result would be no proof of anything whatsoever.” We could not even agree on the meaning of a word if we did not accept that something is itself. Even the word word or the word agree would be meaningless noise if they were not constrained by their identity. It is because we implicitly accept the law of identity that we can communicate and (usually) understand each other.

The law of identity is about recognizing that something is what it is, with all the implications of being what it is. In other words, some things are what they are despite what a person—or the whole world—might wish them to be. Abraham Lincoln once jokingly asked, “How many legs does a dog have if you call the tail a leg?” His answer? “Four. Calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it a leg.” The law of identity may seem obvious, but it has significant relevance for the way we live our lives. All of us, not just philosophers, must accept the implications of this law: failure to recognize—and act upon the recognition—that something is itself can lead to dire consequences. If, for example, a person treats a truck as something that it’s not—as, say, a flower—then this person is in danger of being run over; similarly, if he deals with poison as if it were food then he will most likely die.

When we say that something has an identity, we are saying that it has a specific nature. A truck, for example, is solid, hard, of a certain mass, and so on; poison has a particular chemical makeup, it acts in a specific manner when it enters the bloodstream, and so on. Living in accordance with the law of identity and the law of noncontradiction is not optional—it is a necessity.

It is not uncommon for philosophers or politicians to come up with an ethical or a political system that does not take into consideration the law of identity. Refusing to accept that a human being is a human being while prescribing codes of behavior for society is like crossing the street while refusing to recognize the nature of a truck—and the consequences are just as serious, only in the case of ethics or politics, on a far greater scale.

While most people find it easy to respect the law of identity when it comes to physical objects like trucks or poison, many of us have a harder time when it comes to our feelings, especially if these feelings are unwanted because they threaten our sense of who we are. If it is important for me to see myself as brave, I may refuse to accept that I sometimes feel fear; if I think of myself as generous, it may be hard for me to accept feelings of envy. But if I am to enjoy psychological health, I need first of all to accept that I feel the way I do. I need to respect reality.

Psychologist Nathaniel Branden regards respect for reality as the foundation of mental health.4 Self-acceptance—whether accepting the reality of my emotions, my failures, or my successes—is taking the law of identity and applying it to human psychology. In Branden’s words, “Self-acceptance is, quite simply, realism. That which is, is. That which I feel, I feel. That which I think, I think. That which I have done, I have done.” And just as the law of identity forms the foundation of any coherent and logical philosophy, so is self-acceptance the foundation of a healthy and happy psychology.

![]()

Think of experiences that you have had in which you or someone else failed to respect reality and ignored to some extent the law of identity. What was the outcome?

The Emotion Is the Emotion

In children, violating the law of identity where emotions are concerned can engender perfectionism, and this despite the best-intentioned child-rearing practices. When a parent of a child who is angry says, “You can’t be angry over this little thing, can you?” he is challenging the child’s actual feeling, encouraging the child to deny the reality of her anger. What the child hears is, “Your anger is not anger.” When a child tells her brother, “I hate you,” and the parent says, “You don’t really hate your brother, you actually love him, don’t you?” the parent is negating the existence of an emotion that exists. He is in fact saying, “Your emotion is not really the emotion”—something is not itself.

The most important work on communicating with children was carried out by psychologist Haim Ginott, who, in his book Between Parent and Child, writes, “Many people have been educated out of knowing what their feelings are. When they hated, they were told it was only dislike. When they were afraid, they were told there was nothing to be afraid of. When they felt pain, they were advised to be brave and smile.”5 Ginott advocates telling children the truth instead—that hate is hate, that fear is fear, that pain is pain. The parent’s role, Ginott says, is to place a mirror to the child’s feelings, to teach him about his emotional reality by reflecting his emotions back to him and making them visible, without distortion or analysis: “A child learns about his physical likeness by seeing his image in a mirror. He learns about his emotional likeness by hearing his feelings reflected by us.” Just as a mirror does not preach to us but merely shows us what is, a parent should not preach to a child who is in an emotional storm. It is often enough to say, “I see that you are really sad about what just happened” or “It seems to me that you are really feeling angry” to dispel the sadness or anger.

I first read Ginott’s book when I was in college and then again when I became a parent and really needed his advice. It never ceases to amaze me how well his approach works, how fast the turnaround can be when the child feels that his feelings are understood. This morning, for instance, David got worked up about the new Superman cap that we bought him yesterday.

“It’s too big and I hate it!” he said. “It keeps falling off my head. I hate it!”

I wanted to make him feel better. I also wanted to use the opportunity to teach him that a reaction should be in proportion to the problem. I asked him with empathy, “Aren’t you exaggerating a little?”

His response came faster than the speed of Superman. In a loud voice he uttered something that must have been in Kryp-tonian and started hitting the sofa with the cap. My approach, clearly, was not working.

Fortunately, Ginott, the superpsychologist, came to the rescue, and I changed my tack: “It upsets you, doesn’t it, when the cap you like so much doesn’t fit you?”

David paused for a moment, looked at me, and said, “Yes.”

I continued, “You were so much looking forward to wearing it to day care today, and now it’s too big. What a bummer.”

“Yes, I really wanted to wear it today.”

And then, almost instantaneously, his entire demeanor changed. With a smile on his face, he started walking around the room on his tiptoes. “Daddy, look,” he said, “I’m walking like a dinosaur.” The crisis was over.

Now, do I think that an ill-fitting Superman hat is a major issue, on a par with, say, the fact that some people do not have enough money for basic clothing? Of course not, and my initial instinct was to make sure David understood that. At the same time, do I think that David’s emotions are important, and do I want David to think that his emotions are important? Absolutely, and that is what Ginott reminded me: “When a child is in the midst of strong emotions, he cannot listen to anyone. He cannot accept advice or consolation or constructive criticism. He wants us to understand him.” Ginott continues:

A child’s strong feelings do not disappear when he is told, “It is not nice to feel that way,” or when the parent tries to convince him that he “has no reason to feel that way.” Strong feelings do not vanish by being banished; they do diminish in intensity and lose their sharp edges when the listener accepts them with sympathy and understanding. This statement holds true not only for children, but also for adults.

If emotions are running high when we interact with our children, our partners, or anyone else (including ourselves), acknowledging the feelings that are present is often the best thing to do. This can mean holding in check the inclination to help, to preach, to teach, to offer advice. Despite my good intentions, I was heading toward failure by ignoring David’s emotions: David would have learned nothing from my sermonizing, and both of us would have been left feeling dissatisfied with our emotional interaction. Instead, Ginott’s approach helped me reach a result that benefited everyone: David learned that his emotions matter, I showed him that I understood him, and both of us felt better. And as for the lessons about proportionality and gratitude, I’ll find another opportunity to teach him when he is not so worked up.

Clearly, genuine acceptance of our own or others’ feelings does not resolve everything. We often need to invest considerable effort and time to work through serious issues. Nonetheless, acceptance is an important first step that has both short-term and long-term implications. In addition to toning down the intensity of the emotion itself, something that, amazingly, can happen almost instantaneously, the long-term effect of reflecting back emotions is that it teaches respect for the law of identity, for reality.

![]()

Think of times when you or others were in emotional turmoil. Were the emotions acknowledged? Make a mental note to apply the law of identity the next time you or others experience some difficult emotions.

The Optimal Journey

We are constantly bombarded with perfection. Adonis gracing the cover of Men’s Health and the flawless Helen on the cover of Vogue; women and men on the larger-than-life screen, resolving their conflicts in two hours or less, delivering their perfect lines, making perfect love. We’ve all heard the self-help gurus tell us that there is no limit to our potential, that what we can believe we can achieve, that where there’s a will there’s a way. We’ve been told that we can find perfect bliss if only we follow the road not taken or the road taken by our serene spiritual leader—the one with the best smile on the cover of the New York Times bestseller.

But is this picture-perfect ideal that movies, magazines, and books paint for us real? Is the flesh and blood behind the Adonis picture wholly satisfied with his relationships or his investments, and does he not feel threatened by next month’s cover boy? Is the non-digitally-enhanced Helen totally happy with her skin or SAT scores, and is she indifferent to the ticking of the clock and the omnipresent force of gravity?

The antidote to perfectionism, and the prescription for optimal-ism, is acceptance of reality, of what is, be it failures, emotions, or success. When we do not accept failure, we avoid challenge and effort and deprive ourselves of the opportunity to learn and develop; when we do not accept painful emotions, we end up ruminating on them obsessively—we magnify them and deny ourselves the possibility of serenity; and when we fail to accept, embrace, and appreciate success, then nothing we do has real meaning.

Imagine a life of true acceptance. Imagine spending a year in school—reading and writing and learning—without concern for the report card at the end of the ride, accepting success and failure as natural components of development and growth. Imagine being in a relationship without the need to mask imperfections. Imagine getting up in the morning and accepting the man or woman in the mirror.

Acceptance, however, cannot on its own solve the problem of perfectionism, and expecting it to work miracles will only lead to further unhappiness. I do not believe that there is a quick-fix solution for dealing with perfectionism, or with unhappiness in general. In our search for a happier life through acceptance, we inevitably experience much turmoil. Swayed by promises of heaven on earth, lured by sirens in the odyssey toward self-acceptance, we look for perfect tranquility—and when we do not find it, we feel frustrated and disillusioned. And it is, indeed, an illusion that we can be perfectly accepting and hence perfectly serene. For can anyone living sustain the eternal tranquility of a Mona Lisa?

There is no end point in the journey toward optimalism, no final destination where we have completely accepted ourselves—our failures, our emotions, our successes. The place of eternal bliss and serenity, as far as I can tell, exists only in dreams and magazines. So rather than following Sisyphus’s footsteps, why not just drop the burden, let go of the myth of perfection? Why not just be a little easier on ourselves and accept that to fail and succeed is part of a full and fulfilling life, and that to experience fear, jealousy, anger, and, at times, to be unaccepting of ourselves is simply, and perfectly, human.

EXERCISES

![]() Sentence Completion

Sentence Completion

|

Psychologist Nathaniel Branden has developed an exercise called sentence completion, which is about generating a number of endings to an incomplete sentence. The key to doing this exercise is to generate at least six endings to each sentence stem, either aloud or in writing. When doing this exercise, it is important to set aside one’s critical faculties and to write or say whatever comes immediately to mind whether or not it makes sense and regardless of internal contradictions and inconsistencies. Sentence completion is itself about the practice of acceptance—expressing whatever comes up, without barriers or inhibitions. After you complete the exercise, you can go over your responses and identify the ones that make sense to you, the ideas you would like to explore further, and the ones that are irrelevant. You can analyze the endings, write about what you have learned from some of them, and commit to taking action based on your analysis. Here is an example of a sentence stem that I completed: If I accept myself 5 percent more … I will stop working so hard I will not succeed as much I will succeed more I will pursue the things that I love Others will reject me Others will be upset with me I will be more accepting of others Others will be more accepting of me I will no longer need to prove myself constantly I will be calmer |

|

Here are a few sentence stems for you to try out: If I give myself the permission to be human … When I reject my emotions … If I become 5 percent less of a Perfectionist … If I become 5 percent more realistic … If I become an Optimalist … If I appreciate my success 5 percent more … If I accept failure … I fear that … I hope that … I am beginning to see that … Begin with these stems, and then come up with your own. You can do the sentence-completion exercise every day for a month or once a week; you can complete ten sentences in one sitting or do two stems every day.6 |

![]() Get Real!

Get Real!

|

Professor Ellen Langer asked students to assess the intelligence of a number of highly accomplished scientists. The first group of students was given no information on how these scientists attained their success. Participants in this group rated the intelligence of the scientists as extremely high and did not perceive the scientists’ achievements as attainable. Participants in the second group were told about the same scientists and the same achievements, but in addition they were told about the trials, errors, and setbacks the scientists experienced on the road to success. Students in this group evaluated these scientists as impressive—just like the students in the first group did. But unlike participants in the first group, students in the second group evaluated the scientists’ accomplishments as attainable. The students in thefirst group were only exposed to the scientists’ achievements. They saw only one part of reality—the outcome—which is what a Perfectionist sees. The students in the second group were also aware of what the scientists did along the way. They saw reality as a whole—the process and the outcome—which is what the Optimalist sees. |

|

Needless to say, all achievements come in a series of steps—people study for years, endure many failures, struggle, and experience ups and downs before they “make it.” The music world is filled with so-called “overnight successes” who actually worked long and hard before they got their big break. But when we look at the end result, we discount the investment in energy and time that was required to get there, and thus the achievement appears beyond our reach—the work of a superhuman genius. As Langer writes, “By investigating how someone got somewhere, we are more likely to see the achievement as hard-won and our own chances as more plausible… . People can imagine themselves taking steps, while great heights seem entirely forbidding.”7 Write down a goal that you care about, one that you are concerned you may not be able to achieve. In narrative form, describe how you will reach this goal. Include in your story a description of the series of steps that you will take on the road to success, the obstacles and challenges that you will face, and how you will overcome them. Discuss where the pitfalls lie, where you may stumble and fall, and then how you will get up again. Finally, write about how you will eventually get to your destination. Make your story as vivid as possible, narrating it like an adventure story. Repeat this exercise for as many goals as you wish. Consider that well-researched biographies present the reality of success—these accounts break down achievement to its real components. You may want to read biographies of accomplished individuals, especially those who succeeded in areas that interest you. |