The Pursuit of Perfect: How to Stop Chasing Perfection and Start Living a Richer, Happier Life - Tal Ben-Shahar (2009)

Part I. The THEORY

Chapter 1. Accepting Failure

The greatest mistake a man can make is to be afraid of making one.

—Elbert Hubbard

On the evening of May 31, 1987, I became Israel’s youngest-ever national squash champion. I was thrilled to win the championship and felt truly happy. For about three hours. And then I began to think that this accomplishment wasn’t actually very significant: squash, after all, was not a major sport in Israel, and there were only a few thousand players. Was it really a big deal to be the best of such a small group? By the next morning I decided that the deep and lasting satisfaction I craved would only come if I won a world championship. I resolved right then to become the best player in the world. A few weeks later I graduated from high school, packed my bags, and left for England, which was considered the center of international squash. From Heathrow Airport, I took the underground train straight to Stripes, the squash club in Ealing Broadway where the world champion, Jansher Khan, trained. And although he did not know it, that was the day I started my apprenticeship with him.

I followed his every move on the court, in the gym, and on the road. Each morning before heading to the club, he ran seven miles; so I did the same. He then spent four hours on court, playing against a few training partners and working out with his coach; so I did the same. In the afternoon he lifted weights for an hour and then stretched for another hour; so I did the same.

The first step in my plan to win the world championship was to improve quickly, so that Jansher would invite me to be one of his regular training partners. I did in fact improve, and within six months of moving to England, I was invited by Jansher to play with him whenever one of his regular partners could not make it. A few months later I became one of the regulars. Jansher and I played and trained together every day, and when he traveled to tournaments I would join him and either warm up with him before his match or, if the match was not taxing for him (and most matches weren’t), we would play afterward.

Although I improved by leaps and bounds, there was a price. While Jansher had gradually built up to the intensity of his workout regime, I had taken a shortcut. When I arrived in England, I believed I had only two options before me: either to train like the world champion (and become one myself) or not to train at all (and give up on my dream). All or nothing. The intensity of Jansher’s regime far exceeded anything I had ever done before. No matter, I thought: to be a world champion, do as the world champion does.

My body thought differently. I began to get injured with increasing regularity. Initially, the injuries were minor—a pulled hamstring, mild backache, soreness in my knee—nothing that could keep me off the court for more than a couple of days. And I felt confident in my approach, because despite my injuries, I was training the way the world champion trained, and my game continued to improve.

But I was dismayed to find that my performance was much weaker in tournaments than during practice. While I had no problem focusing for hours at a time during practice sessions, intense pre-match jitters kept me awake at night and hurt my performance on the court. Playing the big matches or the big points, I would often choke under the pressure.

A year after moving to London, I reached the final of a major junior tournament. I was expected to win comfortably, having beaten the top ranked players in earlier rounds. My coach was watching, my friends were rooting for me, and a reporter from the local paper was there, ready to let the world know about the bright new star on the squash circuit. I won the first two games easily and was within two points of clinching the match when first my feet, then my leg, and finally my arm cramped. I lost the match.

I had never experienced such cramps during practice, no matter how hard I had trained, and it was clear to me that the physical symptoms were a result of psychological pressure. What held me back on that occasion, and on so many other occasions, was my intense fear of failure. In my quest to become the world champion, failure was not an option. By this I mean that not only did I regard becoming the world champion the only goal worth attaining, but I also believed that only the shortest and most direct route to my goal was acceptable. The road to the top had to be a straight line—there was no time (and, I believed, no reason) for anything else.

But my body, once again, thought otherwise. After two years of doing too much too soon, the injuries gradually became more serious, taking weeks rather than days to heal. Nevertheless, I stuck to my punishing regime. Eventually, at the grand old age of twenty-one, plagued by injuries and strongly advised by medical experts to slow down, I had to give up my dream of becoming the best player in the world. I was devastated, and yet part of me felt relieved: the doctors had provided me with an acceptable excuse for my failure.

As an alternative to a professional athletic career, I applied to college. My focus shifted from sports to academia. But I brought to the classroom the same behaviors, feelings, and attitudes that had driven me on the court. Once again, I believed that I faced a choice of all or nothing, in terms of how much work I needed to do and what kind of grades I had to earn. And so I applied myself to reading every word that every professor assigned, and I tolerated nothing short of perfect grades on all the papers that I wrote and the exams that I took. Working to achieve this goal kept me up at night, and anxiety that I still might fail kept me up long after all the papers were handed in and the exams were taken. As a result, I spent my first years of college in a state of almost constant stress and unhappiness.

![]()

Can you relate to the preceding story? In what ways? Do you know others who have been through, or are going through, similar experiences?

My original plan, when I entered college, was to major in one of the hard sciences. My best grades had always been in science and mathematics. To me, that was reason enough to continue along the same path; it was the most straightforward way to achieve perfect grades. But although I did very well in my courses, my unhappiness and my increasing weariness gradually drew me away from this safe choice, and I began to explore the humanities and social sciences. I was initially uneasy about leaving the hard sciences, with their satisfying, objective truths, and was unsure about the more nuanced—and to me, uncharted—territory of the “softer” disciplines. However, my desire to alleviate the anxiety and unhappiness was stronger than my fear and uneasiness about change, and so at the beginning of my junior year I switched my major from computer science to psychology and philosophy.

It was then that I encountered for the first time the research on perfectionism conducted by David Burns, Randy Frost, Gordon Flett, and Paul Hewitt. I had not realized until then that so many people struggled, to a greater or lesser degree, with the same problems I had. Both the research and the knowledge that I was not alone comforted me somewhat. Initially, I scanned the literature looking for a quick fix to get me from where I was (a maladaptive Perfectionist) to where I wanted to be (an adaptive Perfectionist)—I was still looking for the straight-line solution. But when my attempts failed, I delved deeper into the research, and over time I gained a deeper understanding of the subject, and of myself.

Perfectionism Versus Optimalism

Let’s take a look at the essential differences between the Perfectionist, who rejects failure, and the Optimalist, who accepts it. First, though, it is important to understand that perfectionism and optimalism are not distinct qualities that are entirely independent of each other. No person is 100 percent a Perfectionist or 100 percent an Optimalist. Instead, we should think of perfectionism and optimalism as lying on a continuum, and each of us tends to a lesser or greater degree to one end or the other of the continuum.

In addition, we may be Optimalists in some areas of our lives and Perfectionists in others. For example, we may be quite forgiving of mistakes we or others make on the job but be thrown into despair when our expectations are not fully met in our relationships. We may have learned to accept that our home is not immaculate, but when it comes to our children, we accept nothing less than perfectly behaved overachievers. In general, the more a Perfectionist cares about something, the more he is likely to approach it with the Perfectionist’s particular mind-set. For example, when squash was the center of my life, I experienced intense fear of failure each time I played in a tournament. When I went to college and shifted the focus of my perfectionism to academia, I brought the same paralyzing fear to my studies. By contrast, when I play backgammon, which is a game I enjoy a lot, I do not experience an incapacitating anxiety—or other perfectionist symptoms, for that matter—as it is a less important activity to me (except when I play against my best friend, and chief backgammon rival, Amir).

Expectation of a Perfect Journey

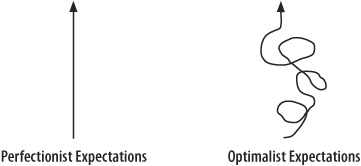

Perfectionists and Optimalists do not necessarily differ in their aspirations, in the goals they set for themselves. Both can demonstrate the same levels of ambition, the same intense desire to achieve their goals. The difference lies in the ways each approaches the process of achieving goals. For the Perfectionist, failure has no role in the journey toward the peak of the mountain; the ideal path toward her goals is the shortest, most direct path—a straight line. Anything that impedes her progress toward the ultimate goal is viewed as an unwelcome obstacle, a hurdle in her path. For the Optimalist, failure is an inevitable part of the journey, of getting from where she is to where she wants to be. She views the optimal journey not as a straight line but as something more like an irregular upward spiral—while the general direction is toward her objective, she knows that there will be numerous deviations along the way.

The Perfectionist likes to think that his path to success can be, and will be, failure free, a straight line. But this does not correspond to reality. Whether we like it or not—and most of us,

Figure 1.1

Perfectionists or Optimalists, do not like it—we often stumble, make mistakes, reach dead ends, and need to turn back and start over again. The Perfectionist, with his expectation of a flawless progression along the path to his goals, is unreasonable in his expectations of himself and of his life. He is engaged in wishful thinking and is detached from reality. The Optimalist is grounded in reality: he accepts that the journey will not always be a smooth straight line, that he will inevitably encounter obstacles and detours along the way. He relies on facts and on reason and is in touch with reality.

Fear of Failure

The central and defining characteristic of perfectionism is the fear of failure. The Perfectionist is driven by this fear; her primary concern is to avoid falling down, deviating, stumbling, erring.1 She tries in vain to force reality (where some failure is unavoidable) to fit into her straight-line vision of life (where no failure is acceptable)—which is like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. When faced with the impossibility of this endeavor, she begins to shrink from challenges, to run away from activities where there is some risk of failure. And when she actually fails—when she sooner or later comes face-to-face with her imperfections, with her humanity—she is devastated, which only serves to intensify her fear of failing in the future.

The Optimalist does not like to fail either—nobody does—but she understands that there is no other way to learn and ultimately succeed. In the words of psychologists Shelley Carson and Ellen Langer, the Optimalist understands that “going off course is not always a negative thing, and it can present choices and lessons that may not otherwise have been recognized.”2 To the Optimalist, failure is an opportunity for receiving feedback. Because she isn’t intensely afraid of failure, she can learn from it—when she fails at something, she takes her time, “digests” her failure, and learns what set her back. She then tries again, and tries harder. By focusing on growth and improvement, and by rebounding from setbacks, she accepts a more circuitous route to her destination than the Perfectionist who insists on a straight line to her goal. But because the Optimalist neither gives up nor becomes paralyzed by the fear of failure, as the Perfectionist so often does, she has a much better chance of actually reaching her goals.

For the Perfectionist the best possible life—in fact, the only life she is prepared to accept—is one devoid of failure. By contrast, the Optimalist knows that the only life possible is one in which failure is inevitable, and, given that constraint, the best possible life is one in which she accepts failure and learns from it.

Focus on the Destination

For the Perfectionist, achieving his goal is the only thing that matters. The process of getting there—the journey—is meaningless to him. He views the journey as simply a series of obstacles that have to be negotiated in order to get to wherever it is that he wants to be. In this sense, the Perfectionist’s life is a rat race. He is unable to enjoy the here and now because he is completely engrossed in his obsession with the next promotion, the next prize, the next milestone—which he believes will make him happy. The Perfectionist is aware that he cannot entirely do away with the journey, so he treats it as a bothersome but necessary step in getting to where he wants to be, and he tries to make it as short and as painless as possible.

In the movie Click, the hero, Michael Newman, is a consummate Perfectionist. He receives a remote control device that enables him to fast-forward his life. Michael’s primary focus is getting promoted at work, which he believes will finally make him happy, so he uses the remote to skip everything he needs to experience on the road to his promotion. He fast-forwards through hard work and hard times but also through all the daily pleasures of life—such as making love to his wife—since they slow down his progress toward his ultimate goal. He considers everything that is not directly related to his end goal an unwelcome detour along the way.

To those around him, Michael seems fully awake, but the effect of using the remote control is that Michael is sedated—not for a few hours to avoid the pain of an operation, but for most of his life—so that he can avoid experiencing the journey, which he perceives as an impediment to his happiness. Michael essentially sleeps through life. Of course, this being a Hollywood movie, Michael realizes the error of his ways and gets a second chance, and this time around he does not make the same mistake: he chooses to experience his life rather than fast-forward through it, and he is a much happier and better person as a result. In real life, Perfectionists who miss everything that matters because they are only focused on their ultimate goal get no second chance.

The Optimalist may have the exact same aspirations as the Perfectionist, but he also values the journey that takes him to his destination. He understands that along the way there will be detours—some pleasant and desirable, some not. Unlike the Perfectionist, he is not so obsessively focused on his goal that the rest of life ceases to matter. He understands that life is mostly about what you do on your way to your destination, and he wants to be fully awake as his own life unfolds.

The All-or-Nothing Approach

The Perfectionist’s universe is ostensibly simple—things are right or wrong, good or bad, the best or the worst, a success or a failure. While there is, of course, value in distinguishing between right and wrong, success and failure—be it in morality or in sports—the problem with the Perfectionist’s approach is that, as far as he is concerned, these are the only categories that exist. There are no gray areas, no nuances or complexities. As psychologist Asher Pacht notes, “For Perfectionists, only the extremes of the continuum exist—they are unable to recognize that there is a middle ground.”3 The Perfectionist takes the existence of extremes to the extreme.

The all-or-nothing approach manifests itself in different ways. When playing squash, my resolve was to train exactly like the world champion, because the only other option I saw was not to train at all. I was solely focused on the goal of winning and didn’t enjoy playing the game. I experienced an inordinate amount of pressure when I played in tournaments, especially if I reached the final, because everything—my total self-worth—hinged on winning a single point, a single game, a single match: either I won the tournament or I was a total loser. For the person consumed by his all-or-nothing approach to life, every deviation—no matter how small or temporary—from the straight line that connects him to his ultimate objective is experienced as abject failure.

I am not suggesting that the Optimalist is a relativist who rejects any notion of winning or losing, success or failure, right or wrong—just because these options signify polar “extremes” on a continuum.4 But the Optimalist understands that while these categories do exist—you won the tournament or you lost it, you succeeded to meet your objectives or you failed—there are also countless points between the extremes that may in themselves be necessary and valuable. An Optimalist would have seen what I could not see when I was following Jansher Khan’s every move—that there are many other options, many of them healthy and appropriate, between training like the world champion and not training at all. An Optimalist can find value and satisfaction—in other words, happiness—in a less-than-perfect performance, something that I was unable to do as a Perfectionist.

Defensiveness

Like failure, criticism threatens to expose our flaws. Because of their all-or-nothing approach, Perfectionists perceive every criticism as potentially catastrophic, a dangerous assault on their sense of self-worth. Perfectionists often become extremely antagonistic when criticized and consequently are unable to assess whether there is any merit in the criticism and whether they can learn from it.

Philosopher Mihnea Moldoveanu writes that when “we say we want the truth, what we mean is that we want to be correct”—a perfect description of the Perfectionist. Like most people, the Perfectionist may say that she wants to learn from others. But she is unwilling to pay the price of learning—admitting a shortcoming, flaw, or mistake—because her primary concern is actually to prove that she is right.

Deep down—or, perhaps, not so deep down—the Perfectionist knows that her antagonistic, defensive behavior hurts her and her chances of success, and yet her whole way of understanding herself and the world makes it very difficult for her to change. There are two particular psychological mechanisms that drive her defensiveness: self-enhancement and self-verification.5 Self-enhancement is the desire to be seen positively by yourself and by others; self-verification is the desire to be perceived accurately by others—to be perceived as you really are (or as you believe you really are). These two mechanisms are often in conflict. For example, a person with low self-esteem may want to look good in the eyes of others (self-enhancement) and at the same time may want to be seen as negatively as she sees herself (self-verification). On the one hand, she wants to be perceived as worthy. On the other hand, her low self-esteem makes her feel unworthy—and so in order to feel that she is being seen for who she really is, she wants to be seen by others as unworthy. Self-enhancement and self-verification are strong internal drives, and whether one or the other dominates when they are in conflict depends on the individual and the specific situation.

When it comes to perfectionism, self-verification and self-enhancement converge, resulting in excessive defensiveness. The Perfectionist wants to look good (self-enhancement), and therefore she tries to appear flawless by deflecting criticism. The picture that the Perfectionist has of herself—the only picture she tolerates—is of flawlessness, and she goes to great lengths to convince others that the way she views herself is indeed correct (self-verification). She will defend her ego and her self-perception at all costs and will not allow criticism that could expose her as less than perfect.

The Optimalist, by contrast, is open to suggestions. She recognizes the value of feedback—whether it takes the form of failure or success when she attempts something or of praise or criticism from others. Though she may not like it when her flaws are pointed out—most people do not enjoy being criticized, just as most people do not like to fail—she nevertheless takes the time to openly and honestly assess whether the criticism is valid and then asks herself how she can learn and improve from it. Recognizing the value of feedback, she actively seeks it and is grateful to those who are willing to point out her shortcomings and her virtues.

Faultfinding

“The fault-finder,” Henry David Thoreau said, “will find faults even in paradise.”6 The Perfectionist’s obsession with failure focuses his attention on the empty part of the glass. No matter how successful he is, his shortcomings and imperfections eclipse all his accomplishments. Because the Perfectionist engages in both faultfinding and all-or-nothing thinking, he tends to see the glass as totally empty—the faultfinding approach finds some emptiness, whereas the all-or-nothing approach takes it to the extreme of total emptiness. Because he is under the illusion that a straight-line journey is possible and that failure can be entirely avoided, he is constantly on the lookout for imperfections and deviations from the ideal path. Seeking faults, he finds them, of course—even in paradise.

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “To different minds, the same world is a hell, and a heaven.”7 Our subjective interpretation of the world matters; what we focus on makes a difference. A less-than-stellar athletic or academic performance, for instance, will be perceived by the Perfectionist as a catastrophe and might lead him to avoid all further challenges. The Optimalist, by contrast, although he will be disappointed by his failures, is more likely to consider them as learning opportunities; failures, rather than paralyze him, may in fact stimulate extra effort. Optimalists tend to be benefit finders—the sort of people who find the silver lining in the dark cloud, who make lemonade out of lemons, who look on the bright side of life, and who do not fault writers for using too many clichés. With a knack for turning setbacks into opportunities, the Optimalist goes through life with an overall sense of optimism.

However, while the Optimalist tends to focus on the potential benefits inherent in any situation, he also acknowledges that not every negative event has a positive aspect, that there are many wrongs in the world, and that at times a negative reaction to events is very appropriate. A person who can never see the negative is a detached Pollyanna, and just as unrealistic as the person who sees only the negative.

Harshness

The Perfectionist can be extremely hard on herself, as well as on others. When she makes mistakes, when she fails, she is unforgiving. Her harshness stems from her belief that it is actually possible (and, of course, desirable) to go through life smoothly, without blunders. Errors are avoidable—they are in her power to avoid—and therefore, she regards being harsh on herself as a form of taking responsibility. The Perfectionist takes the notion of taking responsibility to its unhealthy extreme.

The Optimalist, for her part, takes responsibility for her mistakes and learns from her failures, but she also accepts that making mistakes and experiencing failure are unavoidable. Therefore, the Optimalist is a great deal more understanding when it comes to her failures; she is much more forgiving of herself.

The Perfectionist’s harshness and the Optimalist’s tendency to forgive mistakes extend to the way they treat others. Our behavior toward others is often a reflection of our treatment of ourselves. Being kind and compassionate toward oneself usually translates to kind and compassionate behavior toward others; the converse is also the case, as harshness toward the self often translates to harshness toward others.

Rigidity

For the Perfectionist there is only one way to get where he wants to go, and that route is a straight line. The path he sets for himself (as well as for others) is rigid and static, and the language he tends to use to communicate his intentions is categorical, even moralistic: ought, have to, must, should.

Feelings are irrelevant to his decision-making process. He views them as harmful, because they may change, often in unpredictable ways, and they do not conform to his “musts” and “have tos.” Surprise is dangerous; the future ought to be known. Change is the enemy; spontaneity and improvisation are too risky. Playfulness is unacceptable, especially in those areas that he cares about most, unless the parameters are clear and well defined in advance.

Rigidity in the Perfectionist stems, at least in part, from his obsessive need for control. The Perfectionist tries to control every aspect of his life because he fears that if he were to relinquish some control, his world would fall apart. If he needs to get something done at work or elsewhere, he prefers to do it himself. He does not trust other people, unless he is certain that they will follow his instructions to the letter. His fear of letting go is closely associated with his fear of failure.

Rigidity manifests itself in another way as well. Imagine a person who, committed to his goal of becoming a partner in a consulting firm, spends seventy hours a week in the office. He is unhappy at work and knows that the job at which he felt most fulfilled was when he worked at a restaurant during his summers in college. But he refuses to change his planned course of action—perhaps he even refuses to admit to himself that he is miserable—and continues along the same path toward partnership; regardless of the cost, he refuses to give up on his goal, refuses to “fail” at becoming a partner.

The Optimalist also sets ambitious goals for himself, but, unlike the Perfectionist, he is not chained to these commitments. He might decide, for example, to continue investing time and effort in his goal of becoming a partner at the firm but at the same time relax his schedule slightly, or take some time off, in order to explore whether opening a restaurant might be the right thing for him after all.

In other words, the Optimalist does not chart his direction according to a rigid map but rather based on a more fluid compass. The compass gives him the confidence to meander, to take the circuitous path. While he has a clear sense of direction, he is also dynamic and adaptable, open to different alternatives, able to cope with surprises and unpredictable twists and turns. Accepting that different paths may lead to his destination, he is flexible, not spineless, open to possibilities without being purposeless.

|

The Perfectionist |

The Optimalist |

|

Journey as a straight line |

Journey as an irregular spiral |

|

Fear of failure |

Failure as feedback |

|

Focus on destination |

Focus on journey and destination |

|

All-or-nothing thinking |

Nuanced, complex thinking |

|

Defensive |

Open to suggestions |

|

Faultfinder |

Benefit finder |

|

Harsh |

Forgiving |

|

Rigid, static |

Adaptable, dynamic |

![]()

Can you relate to some of the characteristics associated with perfectionism? How do these characteristics affect your life?

Consequences

Of course, most Perfectionists do not exhibit all of the perfectionist qualities that I have discussed so far. Nor do they exhibit their perfectionist qualities to the same degree in every situation. But the more they exhibit these qualities, the higher their susceptibility to a whole range of disorders, problems, and challenges associated with perfectionism. These include low self-esteem, eating disorders, sexual dysfunction, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosomatic disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, alcoholism, social phobia, panic disorder, a paralyzing tendency to procrastination, and serious difficulties in relationships.8 I will elaborate on a few of these consequences.

Low Self-Esteem

Perfectionism has a devastating impact on self-esteem. Think of a child growing up in a home where, regardless of what he does, he is constantly criticized and put down. Imagine an employee whose shortcomings are constantly highlighted by her boss. Could such a child or an employee enjoy healthy self-esteem? Unlikely. On the contrary, it is likely that, to the extent that they gained any self-esteem elsewhere, it will be squeezed out of them in no time in such an environment. None of us would want to be that child or that employee and live or work under such conditions. Yet the Perfectionist not only lives in precisely this kind of environment; he imposes it upon himself.

Because the life of a Perfectionist is an endless rat race, his enjoyment of success is short lived. He is far more likely to dwell on his failures than on his successes, because when he succeeds in achieving a goal, he immediately starts worrying about the next goal and what would happen if he fails to reach it. The all-or-nothing mind-set leads Perfectionists to transform every setback they encounter into a catastrophe, an assault on their very worth as human beings. Their sense of self inevitably suffers as their faultfinding turns inward.

Today, as I look back on my career as a squash player, I am proud of my efforts, of my dedication to my goal, and of what I accomplished. At the time, though, my self-esteem took a constant beating, as a result of failure or the imminent threat of failure. Very few people then were aware that I suffered from low self-esteem—it was unthinkable to the Perfectionist in me to expose any weakness or imperfection. The Perfectionist constantly engages in self-enhancement, and to the outside world he tries to communicate the flawless facade of what Nathaniel Branden calls pseudo self-esteem: “the pretense at self-confidence and self-respect we do not actually feel.”9

Unlike the Perfectionist, the Optimalist does not reside in a psychological prison of his own making. In fact, over time, the self-esteem of the Optimalist increases. One of the wishes that I always have for my students is that they should fail more often (although they are understandably not thrilled to hear me tell them so). If they fail frequently, it means that they try frequently, that they put themselves on the line and challenge themselves. It is only from the experience of challenging ourselves that we learn and grow, and we often develop and mature much more from our failures than from our successes. Moreover, when we put ourselves on the line, when we fall down and get up again, we become stronger and more resilient.

In their work on self-esteem, Richard Bednar and Scott Peterson point out that the very experience of coping—dealing with challenges and risking failure—increases our self-confidence.10 If we avoid hardships and challenges because we may fail, the message we are sending ourselves is that we are unable to deal with difficulty—in this case, unable to handle failure—and our self-esteem suffers as a result. But if we do challenge ourselves, the message we internalize is that we are resilient enough to handle potential failure. Taking on challenges instead of avoiding them has a greater long-term effect on our self-esteem than winning or losing, failing or succeeding.

Paradoxically, our overall self-confidence and our belief in our own ability to deal with setbacks may be reinforced when we fail, because we realize that the beast we had always feared—failure—is not as terrifying as we thought it was. Like the Wizard of Oz, who turns out to be much less frightening when he is exposed, so failure turns out to be far less threatening when confronted directly. Over the years, by avoiding failure, the Perfectionist invests it with much more power than it deserves. The pain associated with the fear of failure is usually more intense than the pain following an actual failure.

In her 2008 commencement speech at Harvard, J. K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books, talked about the value of failure:

Failure meant a stripping away of the inessential… . I was set free, because my greatest fear had already been realized, and I was still alive, and I still had a daughter whom I adored, and I had an old typewriter and a big idea. And so rock bottom became the solid foundation on which I rebuilt my life… . Failure gave me an inner security that I had never attained by passing examinations. Failure taught me things about myself that I could have learned no other way. I discovered that I had a strong will, and more discipline than I had suspected; I also found out that I had friends whose value was truly above rubies… . The knowledge that you have emerged wiser and stronger from setbacks means that you are, ever after, secure in your ability to survive. You will never truly know yourself, or the strength of your relationships, until both have been tested by adversity.

We can only learn to deal with failure by actually experiencing failure, by living through it. The earlier we face difficulties and drawbacks, the better prepared we are to deal with the inevitable obstacles along our path.

Talent and success without the moderating effect of failure can be detrimental, even dangerous. Until Vincent Foster was appointed President Bill Clinton’s deputy White House counsel, his career ascent had been remarkably smooth. According to one of his colleagues, Foster had experienced no professional setbacks, “Never. Not even a tiny one … he seemed to glide through life.” Then the Clinton administration and Foster’s office came under scrutiny, and he “felt he had failed to protect the President by keeping the process under control.” This perceived failure devastated him, and, unable to deal with anything short of total success, he committed suicide. Nothing in his prior experience had prepared him to deal with the psychological impact of failure.11

This is not to say that failure at any point in life is pleasant or easy (it is neither) or even that there is no such thing as devastating failure. However, not trying so that we can avoid failure turns out to be a lot more damaging to our long-term success and overall well-being than putting ourselves on the line and failing. As the Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard noted, “To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily. Not to dare, is to lose oneself.” When we dare, when we cope, we are much more likely to fail—and there is certainly a price tag on that. But the price of not daring and not failing is a great deal higher.

![]()

Think of a challenge that you took on, something that you dared to do. What did you learn, and in what ways did you grow from the experience?

Eating Disorders

In a review article on the link between eating disorders and perfectionism, psychologist Anna Bardone-Cone and her colleagues cite research suggesting that “the aspect of perfectionism associated with the tendency to interpret mistakes as failures is most strongly associated with eating disorders.”12 Perfectionists are susceptible to eating disorders because in their all-or-nothing mindset only extreme failure or extreme success exist—and therefore, if they are concerned about their body image, the choice that they see for themselves is between being fat or being skinny, binging or starving. There is no healthy middle ground.

The media feeds these perfectionist attitudes. The perfect way to look—the “all” as opposed to the “nothing”—is not left for men’s or women’s imagination but rather shoved in our faces on magazine covers and billboards. The Perfectionist then overlooks the fact that most people do not look like supermodels—and that even supermodels do not look like supermodels. Editing software brushes away natural wrinkles or lines, leaving behind suffering humans in its digital dust.

Being flesh and blood rather than perfected digital images, the Perfectionists always find some fault in their appearance. Their all-or-nothing mind-set magnifies every blemish, every deviation from their idealized image. They become obsessed with the extra two pounds they may have gained or with the wrinkle that they think mars their complexion. Perfectionists then take extreme measures to eliminate these perceived imperfections, whether through repeated plastic surgery, invasive beauty treatments, or starvation.

When Perfectionists attempt to lose weight, they usually adopt an extreme dietary regime, which they then follow to the letter. But when eventually, for whatever reason, they are tempted to take a bite of a forbidden food, their sense of having failed is over-whelming, and they punish themselves both psychologically and physically. Often, they will end up devouring the entire gallon of ice cream they tasted and then gorge on everything else in sight. In their all-or-nothing world, they are either on a perfect regime of dieting or off the diet completely. The irony is that even in the midst of eating the gallon of ice cream, Perfectionists derive little, if any, enjoyment from it; the knowledge that they have failed prevents them from enjoying what they are eating.

Optimalists are not necessarily oblivious to the way they look or to what they eat. However, the standards they hold themselves to are human rather than superhuman. They understand the difference between a multidimensional real person and a two-dimensional picture that has been worked on pixel by pixel. And if they are concerned with following a healthy diet or with their weight, they do not berate themselves if they succumb to temptation once in a while. Slipping up from time to time will not drive them from one behavioral extreme to another: they recognize and accept their own humanity—in other words, their fallibility—and they are compassionate toward themselves. At times, they follow Oscar Wilde’s advice and get rid of temptation by yielding to it—enjoying a delicious scoop of ice cream.

Sexual Dysfunction

Perfectionism is one of the leading psychological causes of sexual dysfunction in both men and women. A man’s expectation of flawless sexual performance may lead to erectile dysfunction. For a woman, the need to perform may be so distracting that she fails to become aroused and enjoy sex. For both sexes, each sexual encounter becomes a test, with potential far-reaching ramifications. The evening is either going to be a mind-blowing love-making session or a total disaster. The all-or-nothing mind-set catastrophizes a single imperfect performance and, through the process of a self-fulfilling prophecy, can lead to impotence in the man and sexual arousal disorder in the woman.

Being overcritical—of one’s own body, of one’s sexual performance, of one’s partner—can lead to diminished enjoyment of sex. Moreover, the focus of the Perfectionist on the destination at the expense of the journey leads to an obsession with orgasms and may actually diminish the pleasure of lovemaking.

Optimalists accept the imperfections of their bodies and their sexual performance as natural and human, and therefore, they are able to enjoy sex. Because they are not focused on the faults they or their partners might discover or uncover, they are free to experience the pleasures of mind and body in love.

Depression

Perfectionists are at risk for depression. This is not surprising when you consider that among the causes of depression are faultfinding, an all-or-nothing mentality, and a focus on the goal to the exclusion of any enjoyment of the journey. We spend most of our life engaged in the journey, because the actual moments when we reach our destinations and achieve our goals are necessarily fleeting. If most of what we derive from the journey is unhappiness and pain, then our life as a whole is unhappy and painful.

As we have seen, Perfectionists have a tendency to low self-esteem because their faultfinding is directed inward, something which can also lead to depression. Depression, however, is also caused when the Perfectionist’s tendency to find fault is directed outward. The potential for happiness is inside us and all around us; unfortunately, so is the potential for unhappiness. And because the Perfectionist finds fault with everything, the actual circumstances of her life matter very little, because she will manage to find something wrong, magnify it out of all proportion, and thus ruin any possibility of enjoying what she has or what she does.

The Optimalist experiences sadness at times, of course, but she takes each difficult experience in stride. She is able to take a “this too shall pass” approach to problems, and, with her focus on the experience of the journey, she spends much of her time in a positive state. Her life is not without its ups and downs. She has moments of deep sadness and frustration too. But her life is not marred by the constant fear of failure or the magnified impact of actual failure.

The Optimalist is also better equipped to handle challenges. Psychologist Carl Rogers identifies the essential progress in therapy as one in which the client realizes that she is “a fluid process, not a fixed and static entity; a flowing river of change, not a block of solid material; a continually changing constellation of potentialities, not a fixed quantity of traits.”13 Rogers is, in essence, describing the Optimalist whose flexibility allows her to learn rather than stagnate, to grow stronger rather than grow weaker, to navigate through treacherous waters rather than sink into emotional disorder.

Anxiety Disorders

Perfectionism not only causes anxiety disorders but can itself be understood as a form of anxiety disorder—failure anxiety. Since the all-or-nothing approach does not distinguish minor failures from major ones, virtually every situation has within it the potential for catastrophe, and this is something that the Perfectionist is always aware of. As a result of obsessively worrying about these “catastrophes” that are just around the corner, the Perfectionist experiences ongoing anxiety and at times panic.

There is another element, though, that accounts for both anxiety and depression among Perfectionists, and that is their rigid, inflexible mind-set. One of the reasons why depression and anxiety are on the rise throughout the world stems from the fast rate of change—markets change daily, technology advances by the nanosecond, and new ways of doing and being are constantly advertised and promoted. The Perfectionist’s fixed and inflexible perception of the right way of doing things, the right way to live, is constantly challenged by the outside world—a world that is fluid and, at times, unpredictable.

Perfectionism was a problem three thousand years ago, but given the relatively static world it was possible to survive and even thrive being a Perfectionist. Today—and increasingly more so by the day—shifting from perfectionism toward optimalism is becoming vital. A rigid mind-set is ill-suited for modern fluidity—which is one of the reasons why levels of depression, anxiety, and suicide rates among the young are rising, in the United States, in China—which is experiencing unprecedented growth—and throughout our flat world.

The Optimalist, being more flexible and open to deviations, is better able to cope with the ever-changing environment. While at times he, too, struggles with change, he has the willingness and the self-confidence necessary to deal with the unpredictable and the uncertain. Change is not a threat but a challenge; the unknown is not frightening but fascinating.

![]()

Are you struggling with any of the issues associated with perfectionism? Where in your life are you an Optimalist?

Success

Many Perfectionists understand that their perfectionism harms them, but they are reluctant to change because they believe that while perfectionism may not make you happy, it does make you successful. Echoing John Stuart Mill’s choice between being an unhappy Socrates and a happy fool, the Perfectionist believes his choice is either to be an unsuccessful (and perhaps happy) slacker and a successful (albeit unhappy) Perfectionist. Not wanting to be a slacker, he chooses the other extreme, placated by his belief in the philosophy of “No pain, no gain.” The Optimalist, however, challenges the Perfectionist’s philosophical rhyme with his own, as he does it “Better with pleasure” (sorry!).

And, indeed, research indicates that while there are, of course, highly successful Perfectionists, all other things being equal, an Optimalist is more likely to be successful. There are a number of reasons why, including the following.

Learning from Failure

To remain employable, let alone competitive, we must constantly learn and grow, and to learn and grow, we must fail. It is no coincidence that the most successful people throughout history are also the ones who have failed the most. Thomas Edison, who registered 1,093 patents—including ones associated with the lightbulb, the phonograph, the telegraph, and cement—proudly declared that he failed his way to success. When someone pointed out to him that he had failed ten thousand times while working on one of his inventions, Edison responded, “I have not failed. I’ve just found ten thousand ways that won’t work.”

Babe Ruth, considered by many the greatest baseball player in history, hit 714 career home runs—a record that held for thirty-nine years. But he also topped the league five times in the number of strikeouts.

Michael Jordan, arguably the greatest sportsman of our time, reminds his admirers that even he is human: “I’ve missed more than nine thousand shots in my career. I’ve lost almost three hundred games. Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

And then there is the man who at the age of twenty-two lost his job. A year later he tried his luck in politics, ran for the state legislature, and was defeated. He next tried his hand at business again and failed. At the age of twenty-seven he had a nervous breakdown. But he bounced back, and at the age of thirty-four, having gained some experience, he ran for Congress. He lost. Five years later, the same thing happened again. Clearly not discouraged by failure, he set his goals even higher and ran for the Senate at the age of forty-six. When that failed, he sought nomination for vice president, again unsuccessfully. Just shy of his fiftieth birthday, after decades of professional failures and defeats, he ran again for the Senate and was defeated. But two years later this man, Abraham Lincoln, became the president of the United States.

These are stories of exceptional people, but the pattern of their stories is common to millions of others who have achieved small or great feats by failing their way to success. Failure is essential in achieving success—though it is of course not sufficient for achieving success. In other words, while failure does not guarantee success, the absence of failure will almost always guarantee the absence of success. Those who understand that failure is inextricably linked with achievement are the ones who learn, grow, and ultimately do well. Learn to fail, or fail to learn.

The comfortable relationship that Optimalists have with failure makes them more willing to experiment and to take risks and makes them more open to feedback. In a study that hit close to home for me, Perfectionists were shown to be weaker writers than non-Perfectionists because “they took pains to avoid allowing other people to view samples of their writing, thereby insulating themselves from feedback that could have improved writing skills.”14 A genuine desire to learn—whether from the feedback of other people or from the feedback that failure itself can provide—is a prerequisite for success, whether one is in banking, teaching, athletics, engineering, or any other profession.

Peak Performance

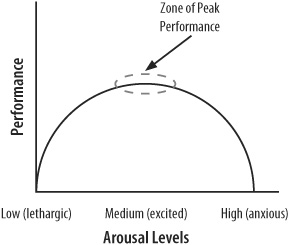

Psychologists Robert Yerkes and J. D. Dodson show that performance improves as levels of mental and physiological arousal increase—until a point when further increase in arousal leads to poorer performance.15 In other words, when levels of arousal are too low (lethargy or complacency) and when levels of arousal are too high (anxiety or fear), performance is likely to suffer. So when are people most likely to perform at their best? When they experience excitement, the midpoint between feeling lethargic and feeling anxious.

Top performers in sports, business, science, politics, and every other area of human achievement are usually very disappointed

Figure 1.2

when their efforts fall short of their high expectations. However, they are not paralyzed by an intense fear of possible failure, and when they do fail (as we all do, from time to time), they do not catastrophize their failures. The combination of on the one hand striving for success and on the other accepting failure as a natural part of life enables them to experience the kind of excitement that leads to peak performance.

Enjoying the Journey

Howard Gardner, among the leading thinkers in the area of education, studied the lives of extraordinary people such as Gandhi, Freud, Picasso, and Einstein, as well as of other accomplished though lesser-known individuals.16Gardner found that it takes approximately ten years of intense work to acquire the level of expertise required to thrive in any field—from business to athletics, from medicine to art. And of course the hard work is not over after ten years—just as much effort, and sometimes even more effort, is necessary to sustain success.

For the Perfectionist, sustaining this sort of effort can be extremely difficult. The Perfectionist’s obsession with the destination and her inability to enjoy the journey eventually saps her desire and motivation, so that she is less likely to put in the hard work necessary for success. No matter how motivated she may be at the beginning, the strain of sustaining an effort for long periods of time eventually becomes intolerable if the entire process—the journey—is unhappy. There comes a point when, despite the Perfectionist’s motivation to succeed, part of her will begin to want to give up, just in order to avoid further pain. No matter how intensely she may want the promotion from middle to senior management, the Perfectionist may find that because the journey is so long—and it always lasts much, much longer than that brief moment when the destination is reached—she cannot bear to sustain it. As a result, she may begin to spend as little time as possible at work and expends as little energy as she can get away with in the accomplishment of her daily tasks.

The Optimalist is able to enjoy the journey while remaining focused on her destination. While she may not necessarily experience a smooth, easy ride to success—she struggles, she falls, she has her doubts, and she experiences pain at times—her overall journey is far more pleasant than the Perfectionist’s. She is motivated by the pull of the destination (the goal she wants to achieve) as well as by the pull of the journey (the day to day that she enjoys). She feels both a sense of daily joy and lasting fulfillment.

There is another way in which focusing only on the destination harms the Perfectionist. Much research illustrates that perfectionism leads to procrastination and paralysis.17 The Perfectionist puts off certain work temporarily (procrastination) or permanently (paralysis) both because work for her is painful and because inaction provides an excuse for failure. If I don’t try, she thinks to herself, I won’t fail. In the perverse logic of the Perfectionist, where only outcomes matter, avoiding failure by avoiding work itself makes a certain kind of sense. By trying to preclude the possibility of failure, however, the Perfectionist is of course also precluding the possibility of success.

Using Time Efficiently

The all-or-nothing approach—the idea that work that is not done perfectly is not worth doing at all—leads to procrastination and, more generally, to inefficient use of time. To do something perfectly (assuming perfection is even possible) often requires extraordinary effort that may not be justified in the context of the task at hand. Given that time is a precious resource, perfectionism comes at a high price.

Where appropriate, the Optimalist will devote to a particular task as much time as the Perfectionist would. But not all jobs are equally important, and not all require equal attention. For instance, making sure that every O-ring is sealed before launching a spacecraft is clearly critical, and nothing short of perfect work should be tolerated. However, it may be less appropriate for an engineer working at the space station to fuss for a long while over the colors of a chart on an internal memo about departmental budgets.

During my first two years in college, I devoted tremendous amounts of time to every assignment in every course, and I studied equally hard for every exam. Over time, as I recognized the heavy toll that perfectionism was taking, I shifted toward the optimalist end of the continuum. My approach changed, and I adopted the 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle.

The 80/20 Rule

This principle is named after Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who observed the 80/20 phenomenon—that, in general, 20 percent of the population of a country owns 80 percent of the country’s wealth, that 20 percent of a company’s clients generate 80 percent of its revenues, and so on. More recently, the principle has been applied to time management by Richard Koch and Marc Mancini, who suggest that we can make better use of our time by investing our efforts in the 20 percent that will get us 80 percent of the results we want to achieve.18 For example, it may take between two and three hours to write that perfect report, but in thirty minutes we may be able to produce a report that is sufficiently good for our purpose.

In college, once I stopped being a Perfectionist who needed to read every word in every book that my professors assigned, I began to apply the Pareto Principle, skimming most of the assigned readings but then identifying and focusing on the 20 percent of the text that would yield the most “bang for the buck.” I still wanted to do well academically. That much hadn’t changed. What did change was my “A or nothing” approach, which had guided me as a Perfectionist. While my grade point average did initially suffer slightly, I was able to devote more time to important extracurricular activities, such as playing squash, developing my career as a public speaker, and, last but not least, spending time with my friends. I ended up not only a great deal happier than I had been during my first two years in college but also, looking at that period in my life as a whole (as opposed to through the narrow lens of my grade point average), more successful. The 80/20 rule has continued to serve me well in my career.

![]()

Think about your 80/20 allocation of time. Where can you do less? Where do you want to invest more?

Perfectionism manifests itself in different ways and to differing degrees in each person. Consequently, some of the characteristics that I have discussed in this chapter may be relevant to some people and not to others. The first step, therefore, is to be open rather than defensive and to identify those characteristics that are relevant to you. The second step is to better understand these characteristics and their consequences. Finally, the last step is to bring about the sought-after change through a combination of action and reflection—by thinking about the Time-Ins and working through the exercises in this book.

Moving toward the optimalist side of the continuum is a lifelong project, one that only ends when life itself ends. It is a journey that demands much patience, time, and effort—and a journey that can be delightfully pleasant and infinitely rewarding.

EXERCISES

![]() Taking Action

Taking Action

|

Research by psychologist Daryl Bem shows that we form attitudes about ourselves in the same way that we form attitudes about others, namely, through observation.19 If we see a man helping others, we conclude that he is kind; if we see a woman standing up for her beliefs, we conclude that she is principled and courageous. Similarly, we draw conclusions about ourselves by observing our own behavior. When we act kindly or courageously, our attitudes are likely to shift in the direction of our action, and we tend to feel, and see ourselves as, kinder and more courageous. Through this mechanism, which Bem calls Self-Perception Theory, behaviors can change attitudes over time. And because perfectionism is an attitude, we can begin to change it through our behavior. In other words, by observing ourselves behave as Optimalists do—taking risks, venturing outside our comfort zone, being open rather than defensive, falling down and getting up again—we become Optimalists. For this exercise, think of something that you would like to do but have always been reluctant to try for fear of failing. Then go ahead and do it! Audition for a part in a play, try out for a sports team, ask someone out on a date, start writing that book that you’ve always wanted to write. As you pursue the activity, and elsewhere in your life, behave in ways that an Optimalist would, even if initially you have to fake it. Look for additional opportunities to venture outside your comfort zone, ask for feedback and help, admit your mistakes, and so on. Have fun with this exercise. Don’t worry if you fail and have to try again. In writing, reflect on how this process of learning from failure applies to other areas of your life. |

![]() Keeping a Journal About Failure

Keeping a Journal About Failure

|

In their work on mindfulness and self-acceptance, psychologists Shelley Carson and Ellen Langer note that “when people allow themselves to investigate their mistakes and see what mistakes have to teach them, they think mindfully about themselves and their world, and they increase their ability not only to accept themselves and their mistakes but to be grateful for their mistakes as directions for future growth.”20 The following exercise is about investigating your mistakes. Take fifteen minutes of your time and write about an event or a situation in which you failed.21 Describe what you did, the thoughts that went through your mind, how you felt about it then, and how you feel about it now as you are writing. Has the passage of time changed your perspective on the event? What are the lessons that you have learned from the experience? Can you think of other benefits that came about as a result of the failure, that made the experience a valuable one? Repeat this exercise two or three additional times, either on consecutive days or over a period of a few weeks. You can write about the same failure each time, or about a different one. |