The Battle of Aleppo: The History of the Ongoing Siege at the Center of the Syrian Civil War (2016)

Chapter 9: The Shifting Goals for Aleppo and the Syrian Civil War

Al-Qaeda and ISIS didn’t just bring foreign fighters to the conflict; their expansion helped change the course of foreign intervention in the country and the perception of Assad, years after he first depicted himself as battling militant Islamist forces. Following ISIS’s declaration of the “Caliphate” in June 2014, the U.S. began conducting airstrikes against the militant group and ultimately formed what would become known as the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition. Similarly, when Turkish tanks crossed the border into Syria in August 2016, the operation may have been conducted alongside FSA forces, but the stated goal was to force ISIS out of Jarabulus. These events necessarily put the U.S.-led coalition and Turkey on the de facto same side as Assad, Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia in terms of the fight against ISIS. Although there was no coordination among the West and the others, and the backing of “moderate rebels” in their fight against the regime continued, rhetoric toward Assad’s future began to soften as well. The notion that Assad must be barred from any transitional or future government was crumbling.

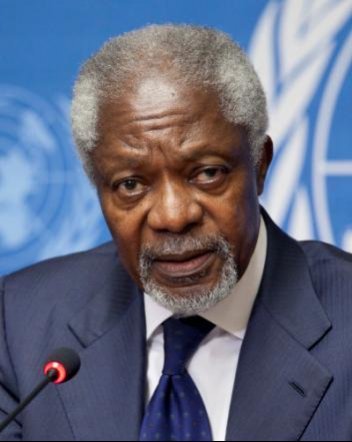

How did the international community[158] get to this point? As noted above, international “intervention” at the start of the Syrian uprising was limited to sanctions, arms embargos, and rhetoric. At that point, divisions between Security Council’s five permanent members prevented any joint action. In the second year of the uprising, in April 2012, the former UN Secretary General and then-UN-Arab League Joint Special Representative for Syria, Kofi Annan, presented the first internationally backed peace proposal to resolve the situation in Syria. In hindsight, it would also be the first of many others to fail. This was referred to as the six-point peace plan and included a parallel UN-supervised cessation of violence and the commitment “to work with the Envoy in an inclusive Syrian-led political process to address the legitimate aspirations and concerns of the Syrian people”. Other aspects included the provision of humanitarian aid to areas affected by the conflict, “the release of arbitrarily detained persons”, freedom of movement for journalists and “a non-discriminatory visa policy for them”, and a promise to “respect freedom of association and the right to demonstrate peacefully”.[159]

Annan

Annan’s plan was verbally accepted by both sides but was short-lived, practically collapsing by June when violence escalated despite the ceasefire provided for in the plan. That month, the United Nations Supervision Mission in Syria (UNSMIS), which was comprised of 300 unarmed monitors and responsible for overseeing the six-point peace plan’s implementation, suspended its normal operations, citing this rise in violence and concerns for the safety of UNSMIS personnel. The mission was then extended for a final 30 days in July, with the UNSC only considering a further extension “in the event that the Secretary-General reports and the Security Council confirms the cessation of the use of heavy weapons and a reduction in the level of violence sufficient by all sides”. This was not achieved and the mandate expired at midnight on August 19.[160] That month, Annan stepped down from his position as joint special representative to Syria, citing the failure of his peace plan and lack of unity in the UNSC.[161]

Two years later, in 2013, the drums of intervention (and war) beat louder when, in August 2013, reports and videos emerged from rebel-held areas in Eastern and Western Ghouta describing an attack involving sarin gas or another nerve agent that killed hundreds of people, including many children.[162] This was not the first alleged use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government, but it was the most severe. The year before, in July 2012, Foreign Ministry spokesman Jihad Makdissi stated “any stock of W.M.D. or unconventional weapons that the Syrian Army possesses will never, never be used against the Syrian people or civilians during this crisis, under any circumstances”. He continued to explain that they would, however, “be used strictly and only in the event of external aggression against the Syrian Arab Republic”.[163] It is important to recall that the Assad regime was depicting the uprising as involving “foreign conspirators”, creating the implication that it could be used during the conflict. Shortly after Makdissi’s statements, Obama articulated his infamous “red line”, stating that “seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized […] would change [his] calculus”.[164]

In the months before the Eastern and Western Ghouta attacks, additional claims of chemical weapons use would emerge. This includes in December 2012 in Homs,[165] which was later determined by a U.S. State Department investigation to be a misuse of riot-control gas, not a nerve agent.[166] But chemical weapons were used in March 2013 in Aleppo city and a Damascus suburb, with both sides accusing the other of responsibility;[167] and the next month more was used in Saraqib, a city in northwestern Syria.[168]

Ultimately, the Eastern and Western Ghouta attacks proved to be a turning point. That month, Obama announced that he would seek Congressional approval to intervene militarily in Syria in response to the use of chemical weapons, which would certainly involve strikes against Assad regime targets. The intervention, however, never materialized. Instead, as was consistent with Obama’s foreign policy philosophy, a joint U.S.-Russian agreement that would allow for the peaceful “control, removal, and destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons capabilities” was prioritized over war. From this came the Framework for Elimination of Syrian Chemical Weapons, which would involve personnel from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the UN, included a schedule of target dates. By November, on-site inspections by OPCW inspections would be completed and production and mixing/filling equipment would be destroyed, while the “complete elimination of all chemical weapons material and equipment” would occur in the first half of 2014.[169] Although the 2014 target date was not met, by January 4, 2016 the OPCW announced the destruction of all chemical weapons declared by the Syrian government.[170] All the while, both analysts and federal government agencies rightly presumed that Assad hadn’t declared all his chemical weapons and had held onto some, and more chemical weapons uses have taken place in violation of the agreements.

Annan’s six-point peace plan would be the last to include any on-ground presence by outside forces, but efforts to forward a real solution to the conflict continued. What later became known as Geneva I but was really an “action group” conference, was held at the end of June 2012. Although parties agreed to a set of “Principles and Guide-lines on a Syrian-led transition” (hereafter “Geneva II communiqué”),[171] disagreement emerged on whether Assad could play any role in a transitional government. Then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated no, sticking to the position of the U.S. that Assad must step down. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, on the other hand, denied that there were any preconditions regarding who may and may not participate in any transitional government.[172]

Lavrov and Secretary of State John Kerry

The Geneva II Conference on Syria subsequently took place in 2014 with the aim of bringing the Syrian government and opposition together in order to discuss the transition agreed upon by Geneva I. In addition to continued disagreement on the future of Assad, the conference’s two rounds yielded no actual negotiations. In fact, parties couldn’t even agree on the proper order of negotiations, with Lakhdar Brahimi, Annan’s successor as UN envoy to Syria, stating that the Syrian government was opposed to the suggestion that the top demands from both sides be discussed, rather than initially focusing on just the government’s.[173]

There would be no successful negotiations of any kind until September 2015, when a limited ceasefire was negotiated and implemented in al-Zabadani, a city located in southwestern Syria’s Rif Damashq Province near the Lebanese border, as well as Fuaa and Kafraya, two Shia majority villages in the Idlib Province. The truce lasted only until October.[174]

That month, attempts were again made in Vienna at the International Syria Support Group (ISSG), which can be considered the most successful conference to date. Often referred to as the “Vienna peace talks”, meetings were held in October and November with the notable participation of Saudi Arabia and Iran. And while disagreement regarding Assad’s role persisted among participating members, point eight in the October joint statement stated that the “political process will be Syrian led and Syrian owned, and the Syrian people will decide the future of Syria”.[175] Based on the aforementioned Geneva II communiqué, the ISSG called for negotiations between the Syrian government and rebels to run parallel to a nationwide cessation of hostilities. There was no mention of Assad in the interest of coming to agreement on a conflict that was about to enter its fifth year. By December of that year, the UNSC had endorsed the November statement and “acknowledge[d] the role of the ISSG as the central platform to facilitate the United Nations’ efforts to achieve a lasting political settlement in Syria”.[176]

Although the Geneva III conference was suspended shortly after it began at the beginning of February 2016, by the end of that month the nationwide cessation of hostilities was agreed to and implemented, although ISIS, al-Nusra Front, and other UN-designated terrorist organizations were excluded. The ISSG Ceasefire Task Force was simultaneously created to exchange information and address issues of non-compliance during the truce.[177] In practical terms, this meant that ISSG member parties would monitor the truce from afar and report violations to the task force. Despite the failure of parallel peace talks and despite allegations of violations,[178] the ceasefire was largely considered to be a success and held until April, when the regime resumed its attack against the opposition-held Aleppo city.[179]

If anything has demonstrated the West’s shifting goals, it is the fact that the only military intervention seen to date by parties backing the opposition came in the form of operations to target ISIS and al-Qaeda, not the Assad regime. Initial airstrikes conducted by the U.S. occurred in Iraq in August 2014 in response to ISIS’s rapid expansion and seizure of territory, as well as the plight of Yazidis, a religious minority perceived by ISIS as heretical and who were surrounded by the militant group.[180] By September, Combined Joint Task Force Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) was formed. “By, with and through regional partners”, its goal is to “militarily defeat Da’esh[181] in the Combined Joint Operations Area”, referring to Iraq and Syria.[182] The first airstrikes against the militant group were reported in Syria that month and, although it is a multi-national coalition, the U.S. has been responsible for the majority of strikes: According to the U.S. State Department, as of July 27, 2016, the U.S. had conducted 4,433 airstrikes in Syria and 6,393 in Iraq, compared to the 249 in Syria and 3,018 in Iraq by other members of the coalition.[183] It is unclear if these numbers include U.S.-only strikes in Syria that targeted the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front and Khorasan Group.[184]

Similarly, Turkey’s August 2016 intervention into Syria had two goals, neither of them being Assad’s removal: Ankara aimed to expel ISIS from Jarabulus, located west of Kobane along the Turkish border, and, in doing so, prevent the Kurds from expanding their territorial control along Turkey’s border. Ankara sees the Kurds as its natural enemy, given their links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been in direct conflict with the Turkish government in the country’s southeast for years.

Diplomatic initiatives and military interventions, therefore, transformed from public disagreements on Assad’s role into an agreement that Syria’s future would be decided by the Syrian people and include a large-scale international intervention that focused exclusively on rolling back ISIS’s expansion. It is no surprise then that public statements from officials, and corresponding attitudes, saw a similar shift from “Assad must go” to “perhaps Assad can be part of the transition”. In September 2015, German Chancellor Angela Merkel stated during a news conference that Assad should be part of negotiations with the West. “We have to speak to many actors”, she explained, “this includes Assad, but others as well”.[185] The next month, then-UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond said that the UK could accept a short transition period that included Assad, albeit with some caveats, including his loss of control over the security establishment and a pledge against running in any future elections.[186] In December of that year, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry told reporters after a meeting with Putin that the removal of Assad is no longer the top priority. Attention, he stated, is “not on our differences about what can or cannot be done immediately about Assad”, but on the pursuit of a peace process that allows “Syrians [to be] making decisions for the future of Syria”.[187] All of these occurred ahead of, during, or after the breakthrough at the Vienna peace talks, whose statement, as previously noted, included no mention of Assad and resulted in the February 2016 ceasefire. Perhaps the most notable shift came from Turkey (discussed further in the case study below) in the summer of 2016, when Prime Minister Binali Yildrim stated on August 20 that Ankara was willing to accept a role for Assad during a transitional period.[188]

This transition in attitudes and rhetoric can be clearly described by one word and demonstrated by the military interventions of the U.S.-led coalition and Turkey: ISIS. It is not that the leaders of the world changed their perception of Assad from that of a war criminal to a benevolent leader; rather, the global threat posed by ISIS caused a change in priorities among those in the “anti-Assad” or “pro-opposition” camp. In other words, targeting this group became more important that removing Assad.

The story of the Syrian conflict, therefore, is also a story of evolving political and military goals. At its onset, efforts focused on pressuring the Assad government into ending the violent repression of protesters and implementing reform; as it continued, these transformed into calls for him to step down. From that point on, Assad was perceived by opposition backers as having no place within a future Syria, a point of contention with Assad’s allies and one of the main obstacles in reaching agreement on a post-conflict transition. As the conflict waged on, however, the emergence, expansion, and overall threat posed by ISIS began shifting attention away from Assad and toward combating the spread of this militant group and its ideology. This shift was further cemented by military intervention that targeted ISIS, not Assad, and a move in rhetoric away from “Assad must go” to either indirect or direct references to a role for Assad in future negotiations or a transitional government. And there is no country that embodies this evolution as clearly as Turkey.

Not surprisingly, resolving the situation in Aleppo is also central to efforts at stopping the war as a whole. In the study of conflict resolution and management, Galtung’s model of conflict explains that conflict can be viewed as a triangle, “with contradiction (C), attitude (A), and behavior (B) at its vertices. Here the contradiction refers to the underlying conflict situation, which includes the actual or perceived ‘incompatibility of goals’ between the conflict parties generated…”[189] The Syrian Civil War at its core is about the mismatching goals of the Syrian government, the initial protesters, and the defectors of the Free Syrian Army. The conflict parties expanded as the chaotic environment of Syria and neighboring Iraq permitted the entry of more parties. Al-Qaeda affiliated groups and other homegrown militias found the opportunity perfect for uprising. The interests of the United States and Russia also have importance here, since their international influence can move pieces in the conflict chess game more quickly than the rebels on the ground.

The city of Aleppo became a focal point for the various parties due to its strategic location and its diverse population with differing views for the path of the country appears to make it a prime breeding ground for factionalism and support during battle. Indeed, Jabhat Fateh Al-Sham, Hezbollah, and the PYD--all paramilitary organizations--found support among their associated ethnic and religious identities in the city.

As the Syrian government continues to surround Aleppo and attempt to force the rebels inside the city into surrender, one might assume the moment is ripe for a peace agreement, but conflict resolution analysis suggests this may actually not be the case. A ripe moment can be understood as a moment in which the warring parties see the situation as one in which they can “find a way out” through peace agreements. However, the conditions for forcing a peace agreement can be tricky. I. William Zartman claims, “The concept of a ripe moment centers on the parties' perception of a mutually hurting stalemate (MHS) -- a situation in which neither side can win, yet continuing the conflict will be very harmful to each (although not necessarily in equal degree nor for the same reasons). Also contributing to "ripeness" is an impending, past, or recently avoided catastrophe. [2] This further encourages the parties to seek an alternative policy or "way out," since the catastrophe provides a deadline or a lesson indicating that pain might be sharply increased if something is not done to settle the conflict soon.”[190]

For the Syrian government, there may indeed be the perception that neither side can win in the war of attrition--particularly inside Aleppo--but as Russia, Iran and Hezbollah continue their current support, they do not necessarily face an ultimatum. The alternative for the regime would be to lose Aleppo, a strategically important location, even as the Syrian government still controls about ⅓ of Syria, including the capital Damascus.[191] As for the rebels--Free Syrian Army, Jabhat Fateh Al-Sham and their allies--they also are not necessarily facing an ultimatum that would force them to lay down their weapons. Indeed, Turkish and Gulf supporters continue to provide assistance and safe zones, especially in northern Syria, for their operations.

Another complication for the rebels is their ultimately objective. The Free Syrian Army is, for the most part, a secular militia focused on toppling Assad and replacing him with a secular government. JFS and their jihadist allies, however, are bent on establishing a Sunni caliphate for the country, a vestige of their Al-Qaeda past and the same exact goal of ISIS. With this in mind, it is not unreasonable to assume at least one of these groups would be a spoiler in negotiations, with the aim of destroying a peace agreement and bringing the parties back into the conflict for their own benefit.

As recently as September 10, 2016, the U.S. and Russia signed an agreement to reduce and eventually end violence in Syria. While skepticism no doubt exists on all sides of the conflict, it is hoped this will be the step toward not only ending the siege and worsening humanitarian crisis in Aleppo but also possibly bringing about the end of the conflict. A reduction in violence is expected to take place in the city so that humanitarian aid can enter the most affected areas. While Russian and Syrian regime strikes are supposed to stop targeting certain rebels, the U.S. will work to encourage rebels to separate themselves from Jabhat Fateh Al-Sham. After this happens, the U.S. and Russia will work together to target areas where ISIS and JFS are present in hopes of eliminating their presence. Ideally, the U.S. and Russia will be able to differentiate between rebel groups and work to eliminate the ones of mutual concern in Aleppo. If this happens, there is hope that after ridding the conflict of the jihadist groups, the warring parties can work toward a long-lasting peace agreement to end the conflict itself.

The results of this agreement remain to be seen, but if past attempts at ceasefires and agreements are any indication, the hopes are slim. After all, Assad and the Russians have constantly branded as terrorists some of the very groups the U.S. has supported, and they may use the guise of the ceasefire agreement to continue targeting groups that aren’t part of Jabhat Fateh Al-Sham or ISIS by claiming there are Jabhat Fateh Al-Sham fighters interspersed with them.The difference here may lie in the fact that there is agreement among both Russia and the U.S. that the most dangerous spoilers at this time are the violence extremist groups, JFS and ISIS. While the U.S. had considered working more closely with JFS in the past since they had even provided lethal aid to other rebel groups during the war, the Syrian government’s concern over Turkish-backed jihadist groups taking over Syria proved more pressing.

Regardless, the battle and sieges of Aleppo have proved to be the most coveted city in all of the Syrian Civil War by all sides of the conflict. The evidence of Aleppo’s cultural and historic significance could already be seen around the city through its architecture, historic markers and diverse inhabitants. Unfortunately, the long battle in this once great city has left a remarkable amount of destruction. This includes the ancient market (souq), the Great Mosque of Aleppo and the larger citadel area [192] Aleppo’s future will bear the scars of the civil war much in the same manner of Beirut following the Lebanese Civil War. The citizens of Syria can only hope that their reconstruction period will lead to development and change toward healing and reconciliation. The amount of violence that has taken place between the different ethnic and religious groups inside of Aleppo and Syria more generally will take many years and monumental efforts on the part of domestic leaders and international partners.

As the ceasefire agreement seems to intend, the battle of Aleppo may very well eventually bring the warring factions to a mutually painful stalemate, but it is unreasonable at this stage to assume that it will happen now. As long as Russia and the U.S. stay involved in a fairly limited way and Turkey continues to influence the Sunni parties, an agreement is unlikely to be successful. The Syrian government and the allies will likely continue to fight over Aleppo and if the city is lost to one group or the other, the conflict will persist in other parts of the country. The challenge, then, will be in how Turkey and the Gulf countries are able to engage with the rebels when they no longer have a direct route like they currently do via Aleppo.

If anything, the story of the Syrian conflict is less clear in 2016 than it was in 2011. Even with direct outside intervention boosting Assad on the battlefield in places like Aleppo, the Syrian regime only controls about a third of the country. The Kurds currently control most of Syria’s border areas with Turkey, while moderate rebels and jihadist groups like ISIS control nearly as much ground as Assad.

Thus, the only safe guess is that political resolutions, Assad’s role after the war, the refugee crisis, and the characteristics of the war will all see more evolution. It may successfully transform into a political transition period with the fight coalescing around a common enemy, or it could cause a disintegration of the country and a division into distinct states based on ethnic or religious identity. The humanitarian and refugee crisis may gradually morph into a process of construction, reconciliation, and repatriation, but it may also continue to the point where intervention in neighboring host countries becomes necessary to ensure their own stability and survival. At the same time, the devastating impact of the conflict on the country’s infrastructure, economy, and population means that even if a political solution is agreed upon and implemented, rebuilding Syria and reconciling the Syrian people will take years, if not decades.

Against this backdrop, there is the long-term implications of ISIS, a threat that will not be resolved by ending the conflict (although it certainly would help). While ISIS’ creation cannot be placed solely on the shoulders of the Syrian government, the group’s ability to expand at the rate and to the extent that it did was a direct result of both the Syrian conflict and circumstances that existed in Iraq at that time. ISIS thrives on war, instability, and discontent, which create vacuums for the militant group, which perceives itself as an actual state with all of its corresponding responsibilities, to enter. Furthermore, ISIS is a brand and ideology that will not disappear even if all the territory under its control is retaken; the group has shown its ability to radicalize from afar. In May 2016, ISIS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani released a recording admitting to losing territory and promising that any future “loss of Raqqa, Mosul and the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi would not mean that [they] have lost”.[193] For ISIS, territorial loss will mean a return to prioritizing asymmetric warfare over governance of the “Caliphate”, that is, implementation of Islamic law, missionary activities, and the like. This is not to say that asymmetric warfare is not already a main component of ISIS’s strategy, since it is. Rather, territorial control requires a division of attention between governance and offensive attacks and, therefore, the loss of this territory means the need to focus only on the latter. In fact, this trend was noted in Iraq in 2016, when increased military offensives corresponded to a loss in ISIS territory and a rise in large-scale attacks away from battlefronts.[194] Thus, the fight against the militant group and its ideology will continue locally and globally, even if Syria and Iraq are stabilized in the future and ISIS is pushed out of the territory it controls.

The legacy of the Syrian conflict, alongside those in Libya, Yemen, and Iraq, may also be an evolution in the way of thinking about modern state borders and nationalism. When one reads formal documents issued by various international bodies, including the UN and Arab League, the concept of respecting Syria’s sovereignty and territorial continuity persistently appears. However, as the conflict has dragged on and divisions along sectarian and ethnic lines have deepened, the notion that the modern state of Syria (with the borders as currently constituted) must be preserved has frequently been challenged by out-of-the-box suggestions with long-standing implications: Will Alawis ever really be safe in a post-conflict Syria in which the majority Sunni population will dominate the state’s various institutions? Why, when it comes to considering solutions to complicated conflicts, are modern state borders so untouchable?

As a result, it appears that the war in Syria will continue indefinitely, with two possible outcomes. It’s possible the country may eventually be partitioned according to religious and ethnic affiliations, similar to the situation in India after it was given independence by Great Britain in 1947, but the more grim possibility is that the war spills over Syria’s borders and becomes regional. Many different nations have competing interests and preferences regarding the outcome of Syria’s civil war, and several of them are taking proactive steps to influence events, including Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia.

Either way, it appears that the war will continue for some time into the future and countless more lives will be lost before it is resolved. The house of cards that is Assad’s presidency may fall, but if so, it will almost certainly be in a manner that is slow and painful for all involved.