The Battle of Aleppo: The History of the Ongoing Siege at the Center of the Syrian Civil War (2016)

Chapter 6: From Civil War to Theater for Foreign Parties

“First of all, you're talking about the president of the United States, not the president of Syria -- so he can only talk about his country. It is not legitimate for him to judge Syria. He doesn't have the right to tell the Syrian people who their president will be. Second, what he says doesn't have anything to do with the reality. He's been talking about the same thing -- that the president has to quit -- for a year and a half now. Has anything happened? Nothing has happened.” - Bashar al-Assad

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines “civil war” as a “war between the citizens of inhabitants of a single country, state, or community”.[70] And, while the Syrian conflict certain began as largely an intra-Syrian conflict involving the Syrian government and a primarily Syrian opposition, the conflict would ultimately see substantial intervention by foreign parties and a significant rise in numbers of foreign fighters. By the time the uprising and subsequent armed conflict entered its 5th year, the use of the term “civil war” was no longer technically accurate.

Indications as to Iranian support for the Assad regime came as early as April 2011, when the IRGC-QF was identified by the U.S. as “providing support to the Syrian General Intelligence Directorate (GID), the overarching civilian intelligence service Syria” that played a key part in repressing protests. Two senior IRGC-QF commanders were also designated “for their roles in the violent suppression of the Syrian people”.[71] Iranian individuals and entities would frequently appear on designations related to the conflict in Syria.

Hezbollah’s support for the Assad regime was also publicly acknowledged, and in August 2012, the U.S. Treasury officially designated Hezbollah “for providing support to the Government of Syria”. In a special briefing given on August 10, U.S. Treasury Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence David Cohen explained that “Hezbollah has directly trained Syrian Government personnel inside Syria and has facilitated the training of Syrian forces by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Qods Force” since the beginning of 2011. Cohen further stated that Hezbollah “also played a substantial role in efforts to expel Syrian opposition forces from areas within Syria”.[72] This public acknowledgment served to legitimize prior allegations that Hezbollah forces were operating alongside Syrian government forces[73] despite denials from Hassan Nasrallah, the group’s secretary general.

Cohen

Nasrallah

This support must be seen within the lens of the aforementioned “Axis of Resistance” and the importance placed on preserving the Assad regime, including in order to retain existing supply routes that moved Iranian arms, equipment, and money into Hezbollah-controlled areas of Lebanon via Syria. Thus, both Iran and Hezbollah would do what they could to prevent Assad’s replacement with a less friendly, pro-U.S., and Sunni government: The U.S.-led intervention in Iraq had transformed a once enemy of Iran’s to a friendly state ripe for its interference and influence, and Tehran wasn’t about to reverse these gains with the loss of Syria.

Initially, the support offered by Hezbollah was limited in “size and scope primarily to advisory and support roles”.[74] Iran’s assistance, provided via the IRGC, was also relatively limited at the start, with reports ranging from participation in arrest operations to technical assistance with blocking communications to the supply of arms.[75] In June 2011, the U.S. Treasury designated Iran Air, the country’s national carrier, for “ship[ing] military-related equipment on behalf of the IRGC since 2006”. This includes to Syria, where “commercial Iran Air flights have also been used to transport missile or rocket components”.[76] Ultimately, these operations were scaled up, corresponding to the outbreak and spread of armed conflict, as well as the deterioration of the country’s armed forces, particularly the Syrian Arab Army (SAA).

However, Iran and Hezbollah would increase the manpower when it looked like the regime was faltering. For example, in July 2015, Assad publicly admitted that there was a manpower shortage; in a televised speech in Damascus, he explained that “sometimes, in some circumstances, we are forced to give up areas that we want to hold onto”. Estimates, moreover, put the number of soldiers as approximately half of the 300,000 it was said to have prior to the outbreak of the conflict.[77] As the regime’s forces became weakened by defections, intense and continuous fighting, casualties, and a substantially more limited population from which to recruit, it naturally became more reliant on deployments of Hezbollah, the IRGC, Iranian-backed Iraqi Shia militias,[78] and Shia Afghans who had sought refuge in Iran from their own conflict and were being recruited in exchange for benefits.[79] The participation of foreign fighters become even more essential as opposition to the draft emerged among regime supporters. In some instances, men turned to desertion, bribery, and even emigration to avoid the draft, primarily due to the growing perception that it meant certain death on the front lines.[80] Thus, as the conflict wore on, “regime forces” evolved from being primarily Syrian, with limited support from Iran and Hezbollah, to being increasingly comprised of Lebanese, Iranian, Iraqi, and Afghani soldiers.

Although these forces share Assad’s goal of remaining in power, it also means that he became progressively reliant on Hezbollah and Iran, a situation from which a number of implications can be drawn. Most obviously, this reliance makes Assad beholden to their [re: Iran’s] interests both at present and in any post-conflict reality that would see his continued involvement. Regionally, the growing need for supplemental forces shifted Hezbollah’s focus from resistance to Israel, its raison d'être, to ensuring the survival of the Assad regime. This is not to say that the group entirely ceased targeting Israel - there was, for example, a limited escalation witnessed between the two in January 2015, triggered by an Israeli airstrike that killed six Hezbollah fighters and an IRGC general in the Syrian Golan Heights.[81] However, Hezbollah’s sizeable commitment to Syria makes the opening of a second front with Israel undesirable, even if the practical battlefield experience gained by its fighters on the ground in Syria may make a future conflict with Israel much deadlier. In an April 2016 article, Voice of America (VOA) quoted an unnamed “Hezbollah commander” as describing Syria as “a dress rehearsal for our next war with Israel”.[82]

Even with the extensive support of foreign forces, the Syrian government continued to face pressure on the battlefield. This eventually led to an expansion in foreign intervention on the side of the Assad regime with the entry of Russia in September 2015. Although couched in terms of combating the spread of ISIS, Russia entered Syria with three main strategic and tactical goals, according to Michael Horowitz, a Syria expert and author of a special report on the intervention. This includes protecting its naval assets in Tartus and expanding Russia’s military presence in the country, including to reduce deployment time for any potential future operations; ensuring the Syrian regime’s viability, including in order to prevent its replacement with a pro-Western government; and develop its deterrence by demonstrating its military readiness and capabilities.[83] In fact, despite the rhetoric that placed combating ISIS as a key reason for its entry into Syria, Russia’s airstrikes “overwhelmingly targeted rebel-held territory in western Syria rather than the ISIS strongholds in the north and east”.[84] And although Russia’s President Vladimir Putin announced Russia’s “withdrawal” in March 2016, Reuters reported that Moscow had shipped more equipment and supplies to Syria, and it continued the airstrikes.[85]

Putin

Russia’s continued involvement, including support for military operations, necessarily meant further evolution. Not only were the regime’s ground forces increasingly filled with foreign fighters, but its air power would also be supplemented by Russian jets. On the ground, Russia placed itself as an essential ally and altered the trajectory of the conflict to be more in Assad’s favor. [86] As a result, in any post-conflict Syria, Iran’s interests would no longer be the only, or even the main consideration. Although relations with Iran appear good (for a brief period in August 2016, Russia even used a base in Iran to launch strikes in Syria), Putin’s priority is to preserve Russia’s influence in Syria, the region, and the world, particularly given that a resolution to the Syrian conflict will involve various international parties. This includes, perhaps even intentionally, at the expense of Tehran’s.

As mentioned above, the initial outbreak of armed conflict in Syria involved, with the exceptions of limited Hezbollah and Iranian support, Syrian security forces on one side and members of the Syrian opposition on the other side, primarily elements that had defected. In other words, it was an intra-Syrian conflict. By the time the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) declared the situation in Syria a civil war[87] and as the conflict dragged on, the composition of the opposition, much like the composition of pro-Assad forces, would become neither exclusively Syrian nor exclusively anything.

Initially, the FSA was formed by defectors from the regime’s forces, and while their banner would be adopted by various emerging armed groups, in practice the leadership maintain limited if any operational control over the events on the ground. These groups and others that would be formed also began diverging in terms of priorities, goals, and backers. Some, including elements of the FSA, want the removal of the Assad regime and the establishment of a pluralistic democratic state.[88] Others prefer a future state with a more Islamist but still democratic character. The Syrian Kurds, represented militarily by the People’s Protection Units (YPG), wanted, and then declared, an autonomous region.

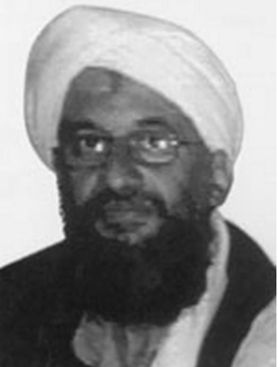

Still others fight for the removal of the Assad regime in order to establish an Islamic state and/or the promotion of global jihad. This includes al-Nusra Front,[89] which was established as a branch of al-Qaeda by the emir of what was then known as the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), the result of the 2006 merger of various militant groups (largest of which was al-Qaeda in Iraq).[90] Despite its links to al-Qaeda, the group has attempted to present a more moderate face to Syria in the world. In 2015, for example, al-Nusra Front commander Abu Muhammad al-Julani claimed that all factions would participate in deciding whether Syria would become an Islamic state, despite this being the publicly stated goal of the organization’s operations there. At one point, he also alleged that al-Qaeda’s leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, ordered al-Nusra Front to refrain from attacking the U.S. or Europe in order to prevent jeopardizing its mission in Syria.[91]

Zawahiri

In its most notable move to date, the group changed its name to Jabhat Fatah al-Sham in July 2016 and announced that all ties with al-Qaeda had been severed. This rebranding was an effort to reposition itself more favorably in Syria, including by removing one of its primary obstacles, that is, the al-Qaeda name. A number of rebel groups were hesitant to unify with the group, particularly given the revelations that a joint U.S.-Russian air campaign to target al-Nusra Front was being discussed. A name change, however, does not mean a change in ideology, and it is questionable whether its ties to al-Qaeda have actually been severed.[92]

Of course, it is impossible to discuss either Sunni jihadist groups in Syria or the conflict as a whole without ISIS. This group’s goal is the creation and expansion of the Islamic Caliphate, which refers to an Islamic state that implements Islamic law and is headed by a caliph, who must be a descendant of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad.[93] ISIS emerged from the April 2013 announcement by ISI’s then-leader, and ISIS’s now caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, that the group had expanded into Syria. Although al-Nusra Front and al-Qaeda central denied any merger with ISI, elements loyal to al-Baghdadi split off to join what would now be called ISIS. The official renouncement of any connection between the two, however, did not come until February 2014, the month after ISIS took control of Raqqah,[94] the provincial capital of Syria’s northeastern Raqqah Province, and Fallujah, a main city in Iraq’s western Anbar Province.[95]

By June, the militant jihadist group would increase the territory under its control to include, inter alia, Mosul, Iraq’s second largest and predominantly Sunni city located the country’s north.[96] That month, the group announced a name change to Islamic State, declared a new Islamic Caliphate, and named al-Baghdadi as the caliph.[97] This announcement would trigger declarations of allegiance and the announcement of ISIS wilayat, or provinces. In addition to the various ones in Syria and Iraq, ISIS “provinces” and affiliates were declared in Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and Russia (North Caucuses region). There is also a “Bahrain Province”, although the only attack to date that this cell has claimed is a shooting that targeted Shia in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province in October 2015, an area where ISIS’s “Najd Province”[98] claimed responsibility for prior attacks.

The militant group’s activity, however, would not be constrained to areas where provinces had been announced; by the summer of 2016, ISIS-directed or inspired attacks would take place in Algeria, Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Indonesia, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Tunisia, Turkey, and the U.S.[99] The amount of territory that ISIS was able to seize, which was assisted by the collapse of the Iraqi military in the face of ISIS’s advance, along with its global spread, are some of the main factors that changed the course of the conflict in Syria and attitudes toward Assad, which will be discussed in further detail below. In short, it caused a shift in priorities to the extent that the West’s fight against the spread of ISIS, both physically and ideologically, would take precedence over all else, including previous insistence on Assad’s removal.

ISIS, along with al-Qaeda, would also change the composition of the Syrian conflict. Although foreign fighters are not exclusive to these two groups, the vast majority of those fighting against the Assad regime in Syria are believed to have joined militant jihadist organizations in general and ISIS in particular. According to a report released by The Soufan Group in December 2015, between 27,000 and 31,000 foreign fighters traveled to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS.[100] Thus, as the war continued, so did the participation of foreigners on the side of both the opposition and regime. If we return to the OED’s definition of “civil war”, it is clear that Syrian conflict could no longer be accurately categorized as such.

As the fighting expanded across the country, so too did its impact on Syrian communities, neighboring states and, subsequently, the international community. Initially, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and the flow of refugees outside of Syria, which began in April 2011, were limited in number, but gradually increased alongside the rise and intensity in fighting. For those who sought refuge outside of Syria, neighboring countries logically became the first destinations. May 2011, for example, saw an influx into Lebanon, largely via unofficial border crossings used for smuggling, following the entry of the Syrian military into Talkalakh, located approximately three miles (less than five kilometers) from the Lebanese border. The next month, the siege of Jisr al-Shughur triggered the flight of 5,000 Syrians out of the city and into Turkey, given its location approximately ten miles (about 16 kilometers) from the border.[101] For those fleeing fighting in the south, Jordan became a logical destination, including for residents of Dara’a, located about four miles (approximately 5.6 kilometers) from the border. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the autonomous region of northern Iraq often referred to as “Iraqi Kurdistan”, also welcomed refugees, many of whom were of Kurdish origin and particularly toward the beginning of 2012.

As fighting escalated, the numbers of IDPs and refugees skyrocketed. According to U.S.Aid, as of May 2016 there were 13.5 million people within Syria in need of humanitarian aid and 6.5 million IDPs.[102] A high number of these also had limited or no access to aid. This can be explained by a number of factors: The expansion of fighting across the country until few areas remained unaffected; the destruction of existing services and infrastructure; the sheer numbers of individuals requiring assistance, which is constantly rising; and the inability to access certain areas, including due to persistent fighting, the expansion of territory controlled by militant jihadist groups like ISIS, and the refusal by the Assad regime to grant entry. In May 2016, for example, Deir Ez-Zor was under siege by ISIS and the delivery of aid was all but impossible, so high altitude airdrops were utilized to provide some level of relief.[103] That June, Darayya, the rebel-controlled neighborhood of Damascus, received in June 2016 its first aid convoy since 2012; previously, Assad had barred access to this area.[104] There have been multiple accusations that the Syrian government was intentionally blocking the delivery of aid to rebel-held areas, in order to “starve out” rebels.[105]

Externally, neighboring countries bearing the brunt of the crisis saw increasing pressure on their infrastructure, economies, and populations as the number of refugees steadily rose. In November 2012, for example, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) stated that 11,000 people had fled Syria over a period of 24 hours to Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, bringing the total number of refugees to 408,000.[106] Almost four years later, as of August 16, 2016, there were 4,808,229 Syrian refugees registered with the UNHCR.[107] Countries like Jordan and Lebanon were also already struggling economically prior to the influx of displaced persons. In 2010, for example, even before the uprising in Syria began, the World Bank reported unemployment in Jordan at 12.5 percent[108] and youth unemployment at a staggering 30.1 percent.[109] In Lebanon, the World Bank put Lebanon’s poverty headcount ratio, referring to the percentage of the population living below the national poverty lines, at 27 in 2012.[110]

In addition to creating further competition for employment, the fact that a large portion of the refugees were not living in camps but, rather, in various communities, caused existing services and institutions to often become overwhelmed in the face of growing populations. The UNHCR also faced, and continues to face, funding shortages;[111] in March 2016, half of the 12 billion U.S.D in funding pledged at a February conference in London had yet to be allocated.[112] All of these factors increased the burden, particularly the financial burden, on host countries, creating serious concerns about their own long-term stability. This includes because the outbreak of the Arab Spring can, in part, be explained in terms of dissatisfaction and anger regarding poor economic conditions and prospects. Recall, for example, Tunisia’s Mohammad Bouazizi, who was from a city with an estimated 30 percent unemployment,[113] and set himself on fire after his produce cart, his method of making a living, was confiscated.

The refugee crisis evolved further by becoming a European crisis, even if this situation cannot be blamed entirely on those fleeing Syria. This “crisis” began in 2015, when approximately one million migrants and refugees entered Europe. According to the UNHCR, of those arriving via the Mediterranean Sea from January 2015 to March 2016, approximately 46.7 percent came from Syria, with Afghanistan in the number two spot at 20.9 percent.[114] To make matters worse for the EU, Erdogan threatened in February 2016 to send the millions of refugees hosted in Turkey to the EU if additional support wasn’t provided. He further stated that the country had already spent nine billion U.S.D since 2011 on hosting these refugees.[115]

One of the methods in which the European Union (EU) approached this issue was through a deal with Turkey in March 2016 that pledged financial assistance in exchange for Ankara curbing the flow of refugees into the EU. This included a concept known as “one-for-one”, which involved the resettlement of a registered Syrian refugee into the EU in exchange for each illegal refugee returned from (primarily) Greece to Turkey, albeit with a cap on this number.[116] In June 2016, the EU Regional Trust Fund also announced a package that included 165 million Euros (approximately 186 million U.S.D) for Turkey to “support education, including school construction and higher education of young Syrians, and extend water and waste-water facilities in southern Turkey”. As part of this package, money, albeit a substantially smaller amount, was granted to Jordan (21 million Euros, or about 23.5 million U.S.D) for the rehabilitation of “overstretched water networks”, and to the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which received 15 million Euros (approximately 16.8 million U.S.D) for assistance to Palestinian refugees that fled Syria. [117]

In addition to evolving from a crisis in Syria to Syria’s neighboring states and Europe, concerns that refugees pose a national security threat also rose to prominence, particularly as the number of ISIS-affiliated and inspired attacks in Western countries rose. A U.S. House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee report issued in November 2015 discussed this issue. It found, among others, that “Islamist terrorists are determined to infiltrate refugee flows to enter the West” and that the U.S. “lacks the information needed to confidently screen refugees from the Syria conflict zone to identify possible terrorism connections”. This was despite acknowledged “security enhancements to the vetting process”. As a result of this, the report went on to explain that “surging admissions of Syrian refugees into the United States is likely to result in an increase in federal law enforcement’s counterterrorism caseload”. In fact, the report’s findings directly cited the situation in Europe, describing their “open borders” as a “‘cause célèbre’ for jihadists” and the Syrian refugee population present already there as being “targeted by extremists for recruitment”.[118] Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has called Syrian refugees a “Trojan horse” for Islamist militants,[119] while the UK vote to leave the EU, referred to as “Brexit”, is often described as a vote against immigration, including the entry of refugees.[120]