The Illustrated Insectopedia - Hugh Raffles (2010)

Generosity (the Happy Times)

1.

On the way to the cricket fight, Mr. Wu slipped us a piece of paper. It looked like a shopping list. “More numbers,” said Michael. He read:

Three reversals

Eight fears

Five fatal flaws

Seven taboos

Five untruths

It was Mr. Wu’s answer to a question I’d asked him earlier that day in the smoke-filled, gold-papered private banquet room upstairs at the Luxurious Garden in Minhang, an industrial district in southwest Shanghai. But it wasn’t the answer we’d expected. Ask him anything you want, said Michael, and I thought we were all relaxed enough, too. Boss Xun and Mr. Tung, the charming gambler from Nanjing, were telling funny stories; tight-lipped Boss Yang was red-faced and expansive; we were toasting health and uncommon friendship. But when I told Mr. Wu that I didn’t yet understand the Three Reversals, he looked straight through me without a smile.

Michael had taken time out from college in Shanghai to work as my translator. But he’d quickly become my full-fledged collaborator. Together, we were trying to find out as much as we could about cricket fighting and what everyone said was its revival. We spent our days running around the city, finding ourselves in places new to both of us, meeting traders, trainers, gamblers, event sponsors, entomologists, and all kinds of experts. By the time we sat down to eat in the Luxurious Garden, we already knew two of the Reversals and suspected the third, and my question was supposed to be an uncontroversial conversation starter. But Mr. Wu was having none of it. Like so many people we met in Shanghai, he wanted us to understand how deep was the world of Chinese cricket fighting—and how shallow were our questions.

2.

As everyone knows, the speed of urban growth and transformation in Shanghai is stunning. In less than one generation, the fields that gave the crickets a home have all but gone. Now, dense ranks of giant apartment buildings, elongated boxes with baroque and neoclassical flourishes, stretch pink and gray in every direction, past the ends of the newly built metro lines, past even the ends of the suburban bus routes. The spectacular neon waterfront of Pudong, the symbol of Shanghai’s drive to seize the future, is barely twenty years old but already under revision. I marvel at the brash bravery of the Pearl Oriental Tower, the kinetic multicolored rocket ship that dominates the dazzling skyline, and think how impossible it would be to build something so bold yet so whimsical in New York. Michael and his college-age friends laugh. “We’re a bit tired of it, actually,” Michael says.

But they also know nostalgia. Only a few years ago, in what seems like another world, they helped fathers and uncles collect and raise crickets in their neighborhoods, among close circles of friends, in and out of one another’s homes and alleyways, sharing a daily life that the high-rise apartments have already mostly banished. Downtown, remnants of that life are visible in pockets not yet rebuilt or thematized. Sometimes, though, residents are merely waiting, surrounded by their neighbors’ rubble, holding out against forced relocation to distant suburbs as the government clears more housing, now for the spectacle of Expo 2010.

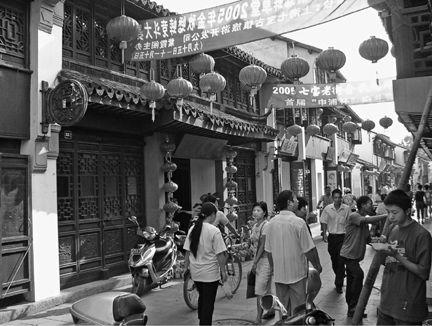

Eleven miles from the city center and a crowded fifteen-minute bus ride from the huge metro terminus at Xinzhuang, the township of Qibao is a different kind of neighborhood. An official heritage attraction, a stroll through a past disavowed for its feudalism during the Cultural Revolution but now embraced for its folkloric national culture, Qibao is newly elegant, with canals and bridges, narrow pedestrianized streets lined with reconstructed Ming- and Qing-dynasty buildings, storefronts selling all kinds of snack foods, teas, and craft goods to Shanghainese and other visitors, and a set of specimen buildings skillfully renovated as sites of living culture: a temple with Han-, Tang-, and Ming-dynasty architectural features, a weaving workshop, an ancient teahouse, a famous wine distillery, and—in a house built specifically for the sport by the great Qing emperor Qianlong—Shanghai’s only museum dedicated to fighting crickets.

All these crickets were collected here in Qibao, says Master Fang, the museum’s director, standing behind a table laden with hundreds of gray clay pots, each containing one fighting male and, in some cases, its female sex partner. Qibao’s crickets were famous throughout East Asia, he tells us, a product of the township’s rich soil. But since the fields here were built on in 2000, crickets have been harder to find. Master Fang’s two white-uniformed assistants fill the insects’ miniature water bowls with pipettes, and we humans all drink pleasantly astringent tea made from his recipe of seven medicinal herbs.

Master Fang has considerable presence, the brim of his white canvas hat rakishly angled, his jade pendant and rings, his intense gaze, his animated storytelling, his throaty laugh. Michael and I are drawn to him immediately and hang on his words. “Master Fang is a cricket master,” confides his assistant Ms. Zhao. “He has forty years’ experience. There is no one more able to instruct you about crickets.”

Everyone at the museum is caught up in preparations for the Qibao Golden Autumn Cricket Festival. The three-week event includes a series of exhibition matches and a championship, with all fights broadcast on closed-circuit TV. The goal is to promote cricket fighting as a popular activity distinct from the gambling with which it is now so firmly associated, to remind people of its deep historical and cultural presence, and to extend its appeal beyond the demographic in which it now seems caught: men in their forties and above.

Twenty years ago, everyone tells me, before the construction of the new Shanghai gobbled up the landscape, in a time when city neighborhoods were patchworks of fields and houses, people lived more intimately with animal life. Many found companionship in cicadas—“singing brothers”—or other musical insects that they kept in bamboo cages and slim pocket boxes, and young people, not just the middle-aged, played crickets, learning how to recognize the Three Races and Seventy-Two Personalities, how to judge a likely champion, how to train the fighters to their fullest potential, how to use the pencil-thin brushes made of yard grass or mouse whisker to stimulate the insects’ jaws and provoke them to combat. They learned the rudiments of the Three Rudiments, around which every cricket manual is structured: judging, training, and fighting.

The irony is that despite the erosion of the popular base needed to guarantee its persistence, cricket fighting is experiencing a revival in China. Even as it loses out to computer games and Japanese manga with the young, it is thriving among older generations. Yet it’s an insecure return that few aficionados are celebrating. For even as the cricket markets flourish, the cultural events blossom, and the gambling houses proliferate, much of the talk is marked by the same anticipatory nostalgia, a sense that this, too, along with so much else about daily life that only a few years ago was taken for granted, is already as good as gone, swept away—not for the first time in recent memory—into the dustbin of history.

Master Fang pulls an unusual cricket pot from the shelf behind him and runs his finger over the text etched on its surface. In a strong voice, he begins to recite, drawing out the tones in the dramatic cadences of classical oratory. These are the Five Virtues, he announces, five human qualities found in the best fighting crickets, five virtues that crickets and humans share:

The First Virtue: When it is time to sing, he will sing. This is trustworthiness [xin].

The Second Virtue: On meeting an enemy, he will not hesitate to fight. This is courage [yong].

The Third Virtue: Even seriously wounded, he will not surrender. This is loyalty [zhong].

The Fourth Virtue: When defeated, he will not sing. He knows shame.

The Fifth Virtue: When he becomes cold, he will return to his home. He is wise and recognizes the facts of the situation.

On their tiny backs, crickets carry the weight of the past. Zhong is not ordinary loyalty; it is the loyalty one feels for the emperor, the willingness to lay down one’s life, to not shirk one’s ultimate duty. Yong is not ordinary courage; it is, once again, the readiness to sacrifice one’s life and to do so eagerly. These are not simply ancient virtues; they are points on a moral compass, codes of honor. As anyone will tell you, these crickets are warriors; the champions among them are generals.

The passage on Master Fang’s pot is from the unquestioned urtext of the cricket community, the thirteenth-century Book of Crickets by Jia Sidao.1 No mere cricket lover, Jia is remembered still as imperial China’s cricket minister, the sensual chief minister in the dying days of the Southern Song dynasty, so absorbed in the pleasures of his crickets that he allowed his neglected state to tumble into rack, ruin, and domination by the invading Mongols. The story is told by his official biographer:

When the siege of the city of Xiangyang was imminent, Jia Sidao sat on the hill of Ko as usual, busying himself with the construction of houses and pagodas. And, as usual, he continued to welcome the most beautiful courtesans, streetwalkers, and Buddhist nuns as his prostitutes and to indulge in his routine merry-making.… Only the old gambling gangsters, looking for play, approached him; no one else dared peek into his residence.… He was squatting on the ground with his entourage of concubines engaged in a cricket fight.2

The historian Hsiung Ping-chen points out that whatever this incident might say about Jia’s sense of responsibility and his personal rectitude, it also casts him as a man whose failings were at least irredeemably human and whose passion for crickets had a democratic stubbornness. From this point on, Jia “was enthroned as the deity in China’s game world,” she writes. “For centuries, his name liberally adorned all covers of books on crickets, call them collections, histories, dictionaries, encyclopedias or whichever title you wish, concerning catching, keeping, breeding, fighting, and, of course, gambling.”3

There is much ambivalence surrounding these crickets, even in this one story. It’s so many things: a sorry tale in which crickets are just another expression of feudal decadence—the counterpoint to socialist modernity and the ready analog for contemporary injustices; a cautionary tale in which the moral effects of compulsive cricket fighting on individual and society are only too plain; a seductive tale in which the problem of desire—with its ever-present threat of addiction or other disorder—is part of the crickets’ magic, in the spell they cast over the most important man in the empire, a spell at once enthralling and enslaving. And more prosaically, it’s a cultural tale in the blandest sense, extending through the centuries, demonstrating the historical reach of crickets as socially important beings, as historical agents of the first degree.

As if all that weren’t enough for one figure (who, of course, had another public career as a politician of considerable importance), there is the Book of Crickets, the very foundation of cricket knowledge, the mostly unnamed source to which everyone—Master Fang, Mr. Wu, Boss Xu—is referring when he tells me that this cricket culture is very deep knowledge, that it comes to us directly from the ancient books. And we can put this in another language to say simply that Jia Sidao’s Book of Crickets is not only the earliest extant manual for cricket lovers, it is also perhaps the world’s first book of entomology.4

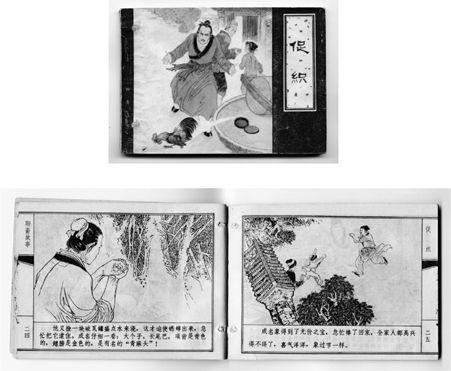

There are written records of people fighting crickets in China as early as the Tang dynasty (618-907). But it’s only with Jia’s Book of Crickets, with its detailing of intimate insect knowledge, that we can be sure that cricket raising and fighting had become a widespread and elaborate pastime. In fact, it was in the 300 or so years between Jia’s Southern Song dynasty and the mid-Ming dynasty that an organized market developed around these animals.5 This market reached its height during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), linking town and country in commerce and culture and stimulating an extraordinarily beautiful material culture of implements and containers.6 It eclipsed the crickets’ older role as singing companions, producing an extensive network of gambling houses with specialized workers and complex rules, an equally energetic but largely ineffectual series of state attempts at prohibition, and—as if it were the expression of Jia’s extravagant desire—sweeping up people of all ages in an activity that was accessible to all social groups and for several centuries was truly popular, as can be seen quite clearly in paintings and poetry and in classic stories like Pu Songling’s “The Cricket,” a tale of bureaucratic oppression and mysterious transformations, a tale of depth, subtlety, and social criticism familiar to everyone I met in Shanghai, a tale that I was able to find in a used-book stall as a finely drawn comic from the early 1980s, a storytelling form once as popular in China as it still is in Japan and Mexico.7

But let’s not lose sight of Jia Sidao just yet. His book is too important and too interesting. It ranges across philosophy, literature, medicine, and lore, as well as the knowledge that falls under today’s more restricted nineteenth-century model of natural history. In its scope it is reminiscent of other great early-modern insect compendia such as book VII of Ulisse Aldrovandi’s De animalibus (1602) and Thomas Moffett’s Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum (1634), the first European books dedicated entirely to insects (which, we might note, were not published until more than 300 years after the Book of Crickets).

Jia’s ambitions were different from those of the European naturalists, and he writes not with their unrestrained desire to assemble and, in their own ways, possess the natural universe but with the more modest impulse to serve the community of gamblers, of which he was a part. Like Aldrovandi’s and Moffett’s volumes, the Book of Crickets is a work of compilation and systematization. But, whereas the impending post-Enlightenment disciplining of European natural philosophy doomed Aldrovandi’s and Moffett’s often-fanciful encyclopedias to long-term obscurity, Jia’s approach is so rigorously empirical and so calibrated to the demands of his fellow insect lovers that—notwithstanding the critical orientation to classical erudition that permeates today’s cricket community and the corresponding periodic complaints about Jia’s unscientific lapses—his detailed diagnostic key to the morphological characteristics of successful warriors is still the basis of cricket knowledge. When Master Fang and other experts tried to instruct me in the distinctions that allow them to judge a cricket’s fighting potential simply by observing the insect in its pot, they used the taxonomy that appeared first in Jia’s Book of Crickets and was modified and supplemented—but not overthrown—across the centuries.

The system is fearsomely complex. It begins with body color. Jia identifies and ranks four body colors: first yellow, then red, black, and finally white. The authoritative Xishuai.com cricket-lovers’ website adds purple and green—for which cricket people always use the ancient term qing—to this list but does not rank them. By contrast, most cricket experts I talked to in Shanghai describe only three colors: yellow, qing, and purple. Yellow crickets are reputed to be the most aggressive of the three but not necessarily the best fighters because qing insects, though quieter, are more strategic and—according to the annual illustrated list of cricket champions—include a greater number of generals.

Color is the first criterion by which crickets are divided and it confers an initial identity that, as we can see, is held to correspond to differences in behavior and character. Below these gross distinctions, however, is a further set of divisions into individual “personalities,” whose total number is often put at seventy-two.8 To entomologists like my friend Professor Jin Xingbao, these personalities relate only to individual—and therefore taxonomically insignificant—variations among crickets that belong to a very limited number of formal species. In the Linnaean terms that she prefers to use, most of the fighting crickets kept in Shanghai are either Velarifictorus micado, a black or dark-brown species that grows to seven tenths of an inch and is highly territorial and aggressive in the wild, or, in smaller numbers, the equally bellicose V. aspersus.9

Because it identifies breeding populations and evolutionary relationships, Professor Jin’s type of classification is essential if, for example, the goal is conservation. However, I suspect she would agree that it’s not much use to cricket trainers seeking ways of identifying potential champions. Their classification system is based on an agglomeration of numerous physical variables, complex clusters of characters.10Length, shape, and color of the insect’s legs, abdomen, and wings are all systematically parsed, as is the shape of the head—current manuals might include seven or more possibilities—and differences in number, shape, color, and width of the “fight lines” that run front to back across the crown. Experts also consider the energy of the antennae; the shape and color of the animal’s “eyebrows” (which should be “opposite” in color to the antennae); the shape, color, translucence, and strength of the jaws; the shape and size of the neck plate; the shape and resting angle of the forewings; the sharpness of the tail tips; the hair on the abdomen; the width of the thorax and face; the thickness of the feet; and the animal’s overall posture. The insect’s “skin” must be “dry” (that is, it must reflect light from inside itself, not from its surface); it must also be delicate, like a baby’s. The cricket’s walk must be swift and easy; it should not have a rolling gait. In general, strength is more important than size. The quality of the jaws is decisive.

Innumerable manuals are dedicated to the identification of especially desirable crickets. Books are filled with color photos of such admirable personalities as Purple Head Golden Wing, Cooked Shrimp, Bronze Head and Iron Back, Ying Yang Wing, and Strong Man That Nobody Can Harm. But as Professor Jin points out, these are ideal types, individual crickets that display prized combinations of traits and are unlikely to recur in precisely this form.

Though from a natural science perspective, this method may appear to be characterized above all by imprecision and taxonomic confusion, it is closer to zoological classification than it might at first appear. The cricket-lovers’ system is a practical one directed at the identification of signs of fighting prowess and the circulation of these signs within the cricket community in a spirit of democratic scholarship. It is also, in its own way, a moral system, a manual of a perhaps archaic masculinity (though it would be foolish to assume that because these characteristics are valued in crickets, they are therefore admired in men). The mastery of such knowledge can require decades of dedicated application, both book study and hands-on learning. It is comprehensive and also intuitive. It is largely inaccessible to a novice. Scientific classification, though substantially more recent and directed to different goals, shares many of these features, and it, too, is based on type specimens—the first individuals of a given category to be collected and described, the specimen against which all subsequent individuals will be measured. Moreover, in both systems, so long as individual variation falls within given parameters, it is disregarded.

Taxonomy doesn’t simply require judgment; it is itself a set of judgments. And it is the key to the early-autumn task of acquiring the best possible insects. As Michael and I were told repeatedly, judging a cricket’s quality requires deep knowledge. Nonetheless, judging is only one of three rudiments of cricket knowledge, and for Master Fang it is of less significance than the work of training, which fills the two-week mid-autumn period between bai lu, when collecting ends, and qiu fen, which marks the official start of the fighting season.

Master Fang tells me that the trainer’s task is to build on preexisting natural virtues to develop the animal’s fighting spirit (dou xing). This indispensable quality is revealed only at the moment the insect enters the arena. Though a cricket might look like a champion in all respects, though the judgment of its physical qualities may be correct, it can still turn out to lack spirit in competition. This, Master Fang insists, is less a matter of the individual cricket’s character than a function of its care. It is the task of the trainer to build up the cricket’s strength with foods appropriate to its stage of growth and individual needs, to respond to its sicknesses, develop its physical skills, cultivate its virtues, overcome its natural aversion to light, and habituate it to new, alien surroundings. Fundamentally, says Master Fang, a trainer must create the conditions in which the insect can be happy. A cricket knows when it is loved, and it knows when it is well cared for, and it responds in kind with loyalty, courage, obedience, and the signs of quiet contentment. In practical terms, this is a quid pro quo because a happy cricket is amenable to training, and as its health, skill, and confidence increase under the trainer’s care, so too does its fighting spirit.

And as he was explaining all this to me, describing the sexual regimen he provides, outlining the many symptoms of ill health that one must be alert to, displaying the purified water, the home-cooked foods, the various pots, explaining that everything relies on communication and that the yard grass is the “bridge” between him and the insect (that, in other words, they understand each other in a language beyond language), Master Fang removed the lid from one of his pots and, in emphatic response to my increasingly unimaginative line of questioning, took his yard grass straw and barked orders at the cricket as if at a soldier: “This way! That way! This way! That way!” And the insect—to Michael’s and my real astonishment—responded unhesitatingly, turning left, right, left, right, a routine of exercises that, Master Fang eventually explained, increases the fighter’s flexibility, makes him limber and elastic, and shows that man and insect understand each other through the language of command as well as beyond it.

Training is a matter of nutrition, hygiene, medicine, physical therapy, and psychology. Each of these is addressed by Jia Sidao in the Book of Crickets, and like the principles of judging a warrior, each has been passed down through the generations of cricket lovers and amended, supplemented, and revised during its travels. Nutrition, hygiene, and medicine now rely both on principles of Chinese medicine—on the requirement to correct imbalances of the five elements with therapeutic baths and appropriate foods—and on the principles of scientific physiology, that is, on the need to find not only cooling and heating foods but also substances rich in, for example, calcium, targeted at the insect’s exoskeleton.

And that’s what Master Fang told me the last time we met. A wild cricket is always superior to one raised from eggs in captivity, he said. And when I asked him why, he answered that the wild animal imbibes specific qualities from the soils of its birth. I at once thought I was hearing him identify a quality in wildness that I also like to hold on to, an ineffable, holistic quality that escapes molecular logic. Hearing this response reminded me of Igarapé Guariba, that village in the Amazon invaded by yellow summer butterflies, and how when Seu Benedito felt ill and prepared remedies for himself, he would leave the mixture outside, near the river, for several days in a capped soda bottle to absorb the nighttime air. That impressed me greatly because to me the bottle was sealed and nothing could enter, but to Seu Benedito those days under the changing sky were a vital ingredient, as essential to the mixture as any of the roots and leaves. But when I asked Master Fang what exactly it was that the cricket absorbed from his environment—Did it get strong by fighting against a difficult climate or inhospitable soil? Were there perhaps atmospheric spirits that fortified its own fighting spirit?—his response was entirely without mystery: the best crickets come not from the harshest soils but from the most nourishing; their characteristic physical powers are a result of their early nutrition; you should look at the soil before you collect; you should know the quality of the earth from which the animal comes; you should administer baths and supplements accordingly.

And as sometimes happened when the topic became more specialized, Michael and I found ourselves in an area in which the experts disagreed. Xiao Fu, an antiques dealer, recently returned from his annual cricket collecting trip to Shandong, explained that the northern crickets are strong precisely because of the harshness of the dry environment against which they have to battle. Mr. Zhang, who generously spent a day taking us to cricket markets in Shanghai, impressing us with his considerable bargaining skills and sharing his substantial knowledge of cricket culture, also preferred wild crickets to home raised but explained that the wild insects absorb their spirit and “soul” from the elements in which they are raised, from the earth, air, wind, and water.

Some months later, when I read Jia Sidao’s Book of Crickets, I discovered that the terms in which Jia described the ecological relationship between land and insect were difficult to specify, that he left room for all these views, but that, like most of the people we talked to about this, he, too, insisted on the importance of the initial environment to the insect’s fighting quality. His discussion of this point won approval from his modern editor, who, though quick to criticize unscientific lapses in the 800-year-old text, interjected only that there was in fact more ecological variation in the crickets’ range than Jia had known of and then, no doubt wisely, declined to arbitrate.

3.

Crickets leap into Shanghai in early August and stay until November. Michael often referred to these three months as the “happy times,” and it took me a while to realize he wasn’t translating this term literally from our conversations with cricket people but extracting it from the pleasure he heard in their accounts. It was an evocative translation, far better than my very English “cricket season.” Even if it ignored the anxieties of what for many was the highlight and sometimes the very purpose of the year, “happy times” captured those irrefutable delights of cricket culture: the play and the camaraderie, the expertise in a world of arcane knowledge, the intimate connection with another species, the willing abandonment to obsession, the security of an erudition that reached back many centuries, and of course, the circulation of money and its possibilities.

The happy times are tethered to the rhythms of the lunisolar calendar, which are themselves tied to the lives of insects. Li qiu, the nominal start of autumn, in early August, is also the time when the crickets in eastern China undergo their seventh and final molt. They are now mature and sexually active, and males are able to sing and—as their color darkens and they gain strength over the following days—ready to fight.

It is now that the happy times officially begin. I haven’t seen it myself, but it’s easy to visualize from the stories: whole villages out in the moonlit fields; young, old, men, women, flashlight bound to the head, listening for the crickets’ song, searching around tombstones, poking the earth and brickwork with sticks, throwing water, pinning the insects like startled rabbits in the beams of light, gathering them in small nets, trapping them in sections of bamboo, taking care not to damage their antennae, carrying them home, ordering them by their diagnostic qualities. In a few days of night- or daytime collecting, a family can amass thousands of crickets, ready to be sold directly to visiting buyers or to be carried to local or regional markets.

Li qiu rings alarm bells throughout China’s eastern cities. In Shanghai, as well as in Hangzhou, Nanjing, Tianjin, and Beijing, it is the signal for tens of thousands of cricket lovers to head for the railway stations. They pack the trains to Shandong Province, which, during the twenty years in which crickets have become scarce in Shanghai, has established itself as the regional collecting center, the source of the finest warriors, known for their aggression, resilience, and intelligence.

Who knows how many answer the crickets’ call and make the ten-hour journey from Shanghai to Shandong? Mr. Huang, feathering a client’s hair in his storefront salon, tells us it can be near impossible to find a rail ticket during this period. Xiao Fu, seated in the doorway of his antiques stall, showing us his collection of rare cricket pots—presenting me with a pair from Tianjin (thick walled and pocket-size to warm the cricket close to your body)—estimates that he is 1 of up to 100,000 Shanghainese who go. Others reckon that 500,000 people arrive from eastern China during this four-week period and that upward of 300 million yuan flows into the local economy from the Shanghainese alone.11

Who travels to Shandong? Always the same answer: if, like Mr. Huang and Xiao Fu, you habitually bet more than 100 yuan on a fight, you make the journey; if, like Mr. Wu, you bet less, you wait for the cricket markets in Shanghai to fill with insects from the provinces and make your selections there. Xiao Fu tells us that he is like most cricket lovers, just a small-to-middling gambler. But the 3,000 to 5,000 yuan he spends each year in Shandong seems sizable next to the 12,000 yuan he brings in from antiques. Still, there are millionaire cricket lovers taking the train these days who are willing to slap down 10,000 yuan to scoop up a single general. So this year Xiao Fu did what more and more visitors do: he rented a car with his friends and toured the villages dotted throughout the countryside on the roads of Ninyang County, and he avoided the crowds in the main market at Sidian.

Often, I’m told, when buyers like Xiao Fu arrive in outlying villages, the first thing they do is pay five yuan for a table, a stool, some tea leaves, a thermos, and a cup. Then, within moments of settling down, they are besieged by villagers pushing cricket pots under their noses, crying, “Look at mine! Look at mine!” Some of the sellers have pricey, good-looking crickets, but others are children and elderly people with only the cheapest insects to sell.12 The more successful sellers establish and maintain connections to buyers, perhaps have them come to the village to trade with them, perhaps even have them lodge in their home. The visitors might be gamblers like Xiao Fu, or they may be Shanghainese traders looking to purchase in bulk. Or they might be wealthier farmers or small businesspeople from local towns and villages who have found ways to cross the far-higher entry barriers to sell on the markets in Sidian or Shanghai or both. Or perhaps they are Shandongnese who do business by selling insects to others—Shanghainese or Shandongnese—who sell them on the urban markets. While it’s clear that for the village collectors who every year turn to crickets for direly needed cash income, this is a moment of real, though perhaps desperate, opportunity, it’s also clear that those who prosper the most in this economy are those who have the most to begin with and that the cricket trade, a vital supplement to the rural economy in Shandong, as well as in Anhui, Hebei, Zhejiang, and other eastern provinces, is also an engine of social differentiation serving to deepen what are already widening chasms of inequality.

Yet it’s an insecure and destructive engine. Through the 1980s and ’90s, as the cricket markets in Shandong took off, the county of Ninjing was the most popular destination for buyers. But after more than a decade of intensive collecting, the quality of the crickets began to decline noticeably, and Ninjing’s preeminence was usurped by its neighbor Ninyang, which now markets itself as “China’s Sacred Fighting-Cricket Location.” In recent years, however, the overexploitation of crickets in Ninyang has forced local collectors (as well as visitors like Xiao Fu) to expand their range, so that they now comb the countryside and villages within a radius of more than sixty miles from their temporary bases. The pressure of unregulated collecting on the crickets is “like a massacre,” writes one contemporary commentator.13 Night hunting, which used to occupy villagers from nine in the evening until four in the morning, now takes them away from their homes until noon.

Just one month after li qiu, as warm August nights ease into cold September mornings and white dew appears on country fields, bai lu marks the end of the collecting season. Sensing the chill in the air, the crickets call a halt, heading back into the soil, digging down with their powerful jaws, weakening their most precious fighting asset, and ruining their value as commodities. Carefully packing up their haul, the last Shanghainese retrace their journey home, though this time they share the trains with Shandongnese traders off to stake their claim in the city’s cricket markets.

At Wanshang, the largest flower, bird, beast, and insect market in Shanghai, these traders, mostly women, sit in rows in the center of the main hall with their crickets laid out neatly before them in small pots with lids cut from tin cans. Around the market’s edges, permanent stalls are occupied by Shanghainese dealers, also newly returned, their clay pots arrayed on tables, the insects’ origin chalked up on a blackboard behind them.

The same pattern is repeated at cricket markets throughout the city. At Anguo Road, in the grim shadow of Ti Lan Qiao, Shanghai’s largest jail, and again in what Michael called new Anguo Road—rapidly opened in a disused lot following a police raid—Shanghainese sellers sit at tables while traders from the provinces, squatting on stools, lay out their pots on the ground in their own distinct areas. This visible geography mirrors pervasive tensions in Shanghai and throughout contemporary China between urban residents and what is officially known as the “floating population,” a vast number of people to whom the government denies urban residency status (with its associated permit and social benefits) but who anyway fill the lowest-paying and most dangerous jobs in the construction, service, and sweatshop sectors.14

Even though the provincial traders at these markets don’t plan to stay in Shanghai and even though they are likely to be relatively prosperous in rural terms (some are farmers; some are year-round traders of various products; one man I talked to dealt in cell phones), once in the city they are simply migrants, subject to harassment, discrimination, and expulsion. Nonetheless, for those who’ve made it here, these are potentially happy times too. No matter that unemployment is up, gambling is down (after a series of police crackdowns), and business accordingly slowed, most expect to do well. By minimizing their expenditures—traveling with relatives, going home infrequently, carrying as much stock as possible when they return, and sleeping in cheap “basement hotels” close to the market—provincial traders can make considerably more in these three months than they will in the entire rest of the year. At least that’s what traders—including an impressively organized woman from Anhui who said that last year she took home a full 40,000 yuan—told me again and again.

Shanghainese traders don’t sell female crickets. Females don’t fight or sing and are valued only for the sexual services they provide to males. It’s the provincial traders who deal in these, selling them in bulk, stuffed into bamboo sections in lots of three or ten, depending on their size (bigger is better) and coloring (a white abdomen is best). Females are cheap, and at a first glance that takes in these traders’ apparently subordinate situation in the market, it seems they sell only cheap animals, female and male.

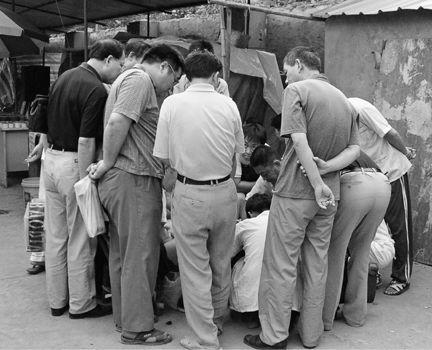

The signs in front of the Shandongnese traders say ten yuan for each male, sometimes two for fifteen. The buyers file past their pots, browsing the rows with an air of detachment, occasionally lifting the lids to peer inside, taking the grass brush, stimulating the insect’s jaws, perhaps shining a flashlight to gauge the color and translucence of its body, trying to judge not only its physical qualities but also that less tangible and even more critical fighting spirit. Despite their studied indifference, they’re often drawn in, quickly finding themselves bargaining for an insect priced anywhere between 30 and—if the buyer is a genuine big boss—as much as 2,000 yuan. Only children, novices like me, the elderly, the truly petty gamblers who play crickets for fun, and bargain hunters who believe their eye is sharper than the seller’s will buy the cheap crickets, it seems.

But how do you judge an insect’s fighting spirit without seeing it fight? Groups of men crowd around the Shanghainese stalls. Michael and I aren’t tall or short enough to see between shoulders or legs. Eventually, someone moves aside to share the view: two crickets locking jaws inside their tabletop arena. The stallholders tend to the animals like trainers at a real fight. But they’re seated in chairs, pots piled around them, and as the match progresses, they deliver relentless patter, inciting interest like auctioneers, talking up the winner and attempting to raise its price.

This is a risky sales strategy. No one buys a loser, so the defeated are quickly tossed into a plastic bucket. And if, as often happens, the winner isn’t sold either, he has to fight again and may be beaten or injured. The seller relies on his ability to inflate the winner’s price enough to compensate for the collateral losses. But the woman from Shanghai who eagerly waves us over as she spoons tiny portions of rice into dollhouse-size trays, tells us that the Shanghainese insist on watching the crickets fight before they put their money down, that they like to shift the risk to the seller. It is starting to look as if the divisions between metropolitan and provincial are expressed not only in the spatial arrangements (which make the market look like an allegorical tableau of society at large) but also in the distinctive selling practices of the different groups, so that buyers stroll in and out of two distinct worlds as they browse, two worlds with explicit boundaries marked by distinct codes, aesthetics, and experiences, two racialized worlds perhaps.

“Shandongnese don’t dare fight their crickets,” the woman continues in a tone that seems congruent with the discriminations that surround us. She is lively and straightforward, generous too, inviting us to share her lunch and giving me a souvenir cricket pot, disappointed that I won’t take the insect as well, enjoying initiating us and not about to be silenced by her irascible husband no matter how many times he looks up from his warriors to sound off in our direction. She’s expounding on her neighbors, the Shandongnese traders. “They sell their crickets as brand-new to fighting,” she says, and then—so casually it almost slips past, and it is only thanks to Michael’s quickness and to the violence of her husband’s reaction that I realize it—she is telling us that crickets circulate throughout the market, unconstrained by social and political division. She explains that they pass not only from trader to buyer but also, without prejudice, from trader to trader, from Shanghainese to Shandongnese and from Shandongnese to Shanghainese. And as they travel through these crowded spaces, they gain and even recover value; they’re born again: losers become ingenues, cheap crickets become contenders; they change their character, their history, and their identity. Caveat emptor.

But how fascinating and even inspiring that the politics of racial difference diagrammed so concretely in this highly spatialized marketplace and conforming so fully (too fully, in a game of double bluff, it turns out) to social expectation is not only an expression of a dismal social logic but also a technology of commerce that creates lively crosscutting dependencies and solidarities. And this thought led me again to the animals who make all this possible, confined to their pots, traveling like slaves really, like chattels, making their way between stalls and pitches, completing circuits, breaching boundaries, and forging new connections, gathering new histories and new lives, unable to prevent themselves from minimizing their captors’ exposure to loss, unable to avoid collaborating in their own demise.

In the city, the happy times have no center; they are everywhere, wherever there are crickets. On working-class street corners, groups of men cram themselves around an arena, watching the battles unfold. In the newspapers, it’s high culture and low life, elite sponsorship and police raids. The happy times bring the gambling houses to life and make possible cultural events and neighborhood tournaments. They light up the stores that sell cricket paraphernalia, the elaborate implements that every fighting cricket and every cricket trainer needs: tiny food and water dishes (maybe in sets with coordinated designs of Buddhist deities), wooden transfer cases, “marriage boxes” with room for one male and one female, various grades of grass and whisker, nudging brushes made of duck down, tiny long-handled metal trowels and other cleaning implements, large wooden carrying cases, pipettes, scales (both weighted and electronic), technical manuals, specialized foods and medicines, and of course, pots in an enormous variety, some old (and often fake), some new, most of clay but some of porcelain, some large, some small, some with inscriptions, mottoes, or stories, some to commemorate special cricket events, some with intricate images, some simply plain.

The happy times are here again. While they last, the money flows, the people travel, and the insects circulate. It’s a period of possibility, an opening in which many projects unfold and many lives are changed. It’s an intense period but a short one. It’s the length of a cricket’s adult life.

4.

Would we see cricket gambling before I left Shanghai? We’d watched crickets fight in Master Fang’s museum, and we’d seen traders “test” them at Wanshang and other markets. But it was all starting to feel like Hamlet without the Prince. Hadn’t gambling and crickets been associated since the earliest records? Hadn’t Jia Sidao written for his gambling friends? Didn’t cai ji, the term for crickets in Shanghainese, mean “collect fortune”? Wasn’t it gambling that made the markets possible and kept cricket fighting alive when so much else considered “traditional culture” was disappearing? Wasn’t it gambling that made these transactions crackle and our conversations pop?

Master Fang, by no means a moralist, did not agree. He said: Gambling debases cricket fighting. And: Cricket fighting is a spiritual activity, a discipline of man and animal. And: Most gamblers know nothing about crickets and have little interest in them; they might as well be betting on mahjong or soccer.

It wasn’t only experience that made Master Fang’s words authoritative. He spoke with a persuasive combination of purism (his master’s rigor) and enthusiasm (his unaffected pleasure in the crickets themselves and the dramas they create). Nonetheless, there seemed something artificial about gambling’s absence. Despite its active exclusion, it always found its way into the tabletop talk. It was as if—for the trainers and audience, if not for the animals—these nongambling fights were merely rehearsals.

But perhaps it was simply timing that made it seem this way. Two weeks later, when the tournament in Qibao reached its final stages, there would be scores, if not hundreds, of people watching the fights in the courtyard of the museum on closed-circuit TV, and as I write this, I remember a Saturday spent in cricket markets with Mr. Zhang, who described how his uncle fought crickets for honor, not money, in the early years of the twentieth century, how in those days the trainers of champions were proud to win red ties, and how, he continued, telescoping the century, cricket fighting began to involve big money only with Deng’s reforms and the spread of disposable incomes. Even in Qibao, though, it was hard to enforce purity and hard to imagine that there was no betting taking place in the wings. The discussion at the museum was all about gambling (winners, losers, champions, bets), with Master Fang as caught up in the gossip as everyone else. Even he admitted that gambling made fights more exciting, that it gave them a raw, compulsive edge.

Still, it didn’t look as if Michael and I would find out for ourselves. It was a too-illegal, too-closed world, and our connections just weren’t good enough. Mr. Huang, the hairstylist, didn’t want to take us. I had just arrived in Shanghai and was wilting under the twin debilities of jet lag and brutal humidity. Michael and I hadn’t yet figured out our translation rhythm, and we made a distinctly unsparky team. The conversation in Mr. Huang’s salon was awkward, and although he was informative and more than courteous, he was wary of taking our relationship further. “It wouldn’t be convenient,” he said decisively.

Xiao Fu, our second contact, was more enthusiastic. His brother, Lao Fu, was an old classmate of Michael’s father, and the four of us quickly hit it off. Xiao Fu was knowledgeable about crickets and generous with his expertise. He brought a selection of his insects and an array of implements to our meeting at his stall and patiently explained many aspects of his passion. Like Mr. Huang, Xiao Fu faced hardships in his life, but he was lucky that in Lao Fu he had a brother who was also a rock, contributing his own expert knowledge of Chinese antiquities to the business and fulfilling a promise to their mother to keep his younger sibling safe and strong. It wasn’t Xiao Fu’s decision not to take us to a fight. The other members of his circle vetoed the proposal and left him with the awkward task of letting us down gently.

In the end it was Mr. Wu, fulfilling an obligation to a friend of his who was also a friend of a friend of mine in California, who made the arrangements. He met us on a dark street corner opposite the model ball bearing factory in the Minhang Heavy Industrial Zone, folded himself into our minuscule Chery QQ taxi, led us to a warren of rundown apartments blocks, through an open front door, and into a side room just big enough for a TV, a fish tank, and a gold plastic love seat.

Mr. Wu was close with the father of Boss Xun, the sponsor of a cricket casino here. Boss Xun not only provided the premises but also handled the local police, guaranteed a referee to arbitrate the fighting and the cash, and made available a secure and well-organized public house. For all this, he and his partner, Boss Yang, took 5 percent of the winnings. Mr. Wu was a cricket lover of the first order and, we would find out, a gifted judge of cricket form, but he was only a small gambler and not a participant in this underworld. It was this discomfort, he later explained apologetically, that accounted for any erratic behavior.

Boss Xun, though, was relaxed and welcoming. Track pants, T-shirt, plastic flip-flops, and a gold chain, gray hair close-cropped, nails carefully manicured, extra-long and tapered on thumbs and pinkies. “Please feel at home,” he said. “Ask me anything you like.” But Mr. Wu was chain-smoking and on edge. I remembered the instructions he’d given us in the cab: no smoking during the fight, no alcohol, no eating, no cologne, no scent of any kind, no talking, no noise of any kind. “We will be like the air,” Michael had assured him.

But it was hard to be unobtrusive. With what I discovered was characteristic graciousness, Boss Xun insisted on seating us at the head of the long, narrow table next to the referee, the best possible view of the crickets and directly opposite the only door. The casino was basic—a whitewashed room stripped bare—and its simplicity was a measure of its transparency. As the men of Boss Xun’s circle entered, they could take in the scene at a glance, the entire room and all its occupants.

A few days earlier, Michael and I had watched a TV exposé of a cricket-gambling den, complete with hidden cameras and pixelated interviewees, and we expected a darkened cellar full of shadowy dealings. But Boss Yang and Boss Xun’s casino was lit by an antiseptic fluorescent strip that threw its glare into every corner, and their table was covered with a white cloth on which sterile implements (yard-grass and mouse-whisker brushes, down balls, transfer cases, two pairs of white cotton gloves—all handled only by their staff) were arrayed with surgical precision on either side of the clear plastic arena.

But transparency and security (windows stuffed with thick cushions to keep noises in and noses out) were perhaps just the enabling conditions. This was serious, but it was entertainment too, men’s entertainment. Boss Xun worked the room with his self-contained charisma, and the referee was engaging and quick-witted. He treated the men in the now-crowded casino with respect, called the bets with finesse, moved everything along swiftly, and managed friction with boisterous humor, all despite the large amounts of money flying across the table.

“Who will call first?” the referee began, addressing the trainers on either side of him. Their motions were slow and deliberate, densely concentrated. They had pulled on the white gloves, lifted the lids from the pots to examine their animals, and aroused them with the yard grass, and now they were delicately transferring them to the arena. One man was a little clumsier, faltering as he eased his fighter out of the transfer case, sweating slightly, his hand trembling slightly, knowing that much of the betting happens before the animals are even visible, that many people wager on the trainers more than on the insects. As the crickets emerged under the lights, everyone leaned in, strained for the closest view, hungry for that moment when the animals’ spirit, power, and discipline would come into the open.

For several minutes, the bets mounted on one animal, then on the next, stopping only when the second pile of cash in front of the referee had grown to equal the first. The packed and steamy room turned raucous. Men with fistfuls of 100-yuan notes clamored to have their bets acknowledged by the referee or, once the house bets had closed, called odds to entice others with whom they might deal laterally. The referee’s voice boomed above the rest, building up the crickets and the stakes. Some men loudly offered commentary on the animals and the wagers. Others simply watched. (And observing these men, Michael—without animus of his own but in an effort to convey to me the resonances that haunt the gambler’s world—recalled one of the scathing essays on political passivity and complicity that the great Lu Xun wrote during the turmoil of the 1930s. Michael couldn’t reproduce the exact wording, and I haven’t managed to find the text, but the gist was clear and, as he remembered it, sour too: We Chinese like to say we love peace, but in reality we like fighting. We like to watch other things fight, and we like to fight among ourselves.… Let them fight; we do not get involved, we just watch.)

And then, at the instant the referee directed the trainers to prepare their crickets, silence snapped into place; the room seemed to hold its breath. The two trainers began again to stroke their animals gently with the yard grass (back legs, abdomen, jaws). The crickets remained motionless. If you were close enough, you could see the beating of their hearts.

Eventually, the insects sang, indicating their readiness. The referee called, “Open the floodgate!” and lifted the panel that divided the arena. Around the table, postures stiffened, the silence intensified. And at once, it was obvious to Michael and me that these animals were far more combative than any we’d seen before, more—we had to say—warrior-like. They looked conditioned, ready. A sudden assault, a dart, a lunge at an opponent’s jaw or leg, and the room emitted a sharp, involuntary gasp. All the energy in this tightly packed space concentrated on this tiny drama. A singularity. And at that moment, I realized I was right there, and I looked at Michael squeezed in beside me and saw that he was too, everything focused on the insects.

Yes, this is typical of a gambling house in the industrial zone, Mr. Wu tells us later as we pour out of the building, flooding the empty streets of the housing projects, everyone lighting cigarettes, muffled talking, car doors slamming. Downtown, the sponsors rent hotel suites and handpick their high-rolling punters, he says, and at those places the minimum bet is 10,000 yuan and the total stakes can far exceed 1 million. Tonight in Minhang, though, the referee opened the bidding with modest encouragements: “Bet what you like, we’re all friends here, even one hundred is fine tonight.” Still, at one point during the evening, as the stakes climbed over 30,000 yuan, Mr. Tung, the gambler from Nanjing, showed his hand for the first time and with no change of expression—almost, it seemed, absentmindedly—tossed a bankroll of 6,000 yuan into the middle of the table and then watched impassively as the referee delegated an observer to count and recount the cash until the gate was lifted in the arena and the crickets rapidly and aggressively locked jaws, wrestling, flipping each other over, again and again, incredibly lithe, a blur of bodies, circling each other, hurling themselves at each other. And then—as if abruptly losing interest—disengaging, walking away to opposite corners and refusing their trainers’ attempts to incite them back into the fray. Even the referee’s effort to stimulate them by eliciting singing from the two crickets kept for this purpose in pots beside the arena had no effect. It was a draw, a rare outcome, which provoked a contemptuous clucking from Mr. Wu, who stage-whispered to us that really good crickets fight to exhaustion, that although athletic and well matched, these animals were poorly trained.

Afterward, with the fighting over, it was as if a spell had broken. It was only then that I wondered about the violence of this spectacle, about the sovereignty that forces other beings to perform such unwonted acts, about cruelty, and yes, about my failure to wonder. Well, you might say, the ethical suspension (if that’s what it was) is unsurprising; the affinities are not so visceral. These are insects, after all—no red blood, no yielding soft tissue, no untoward vocalizations, no expressive faces—not dogs, not songbirds, not even roosters, certainly not boxers wrestling the stark brutalities of race and class.

And yet that concentrated “being there” that Michael and I experienced during the fight was grounded in sympathy for these animals, and it felt like a more profound sympathy than that more familiar feeling of pity-sympathy for animals in distress. Perhaps it was a case of being swept away in the intensity that gripped the room, perhaps it was a case of the magic of money and risk. Even so, the wave that carried us was a wave of identifications shaped by the cultural literacy we were learning from Master Fang, Mr. Wu, and the rest. There was no question about that.

It had been such a short time—less than two weeks in the country of the crickets—yet already I was having trouble separating these animals from their social selves (their virtues, their personalities, their circulations), and already, to me at least, these fights were their fights, their dramas. But I want to be clear about this: the power of this association between the elaborate culture of the cricket-lovers’ world and the crickets themselves, the ability of this alliance to produce an effect that those of us not accustomed to thinking of ourselves as ontologically entangled with insects might experience as a suspension of the order of natural things (such that these animals were neither objects nor victims nor even a simple projection of human aspiration), is possible only because of the insects themselves, which are not merely the opportunity for culture but its co-authors. (And here is a moment when, yet again, language—at least, the English language—is not adequate to its task, because even to write about the “association” between the crickets and their cultural selves is absurd. What is a cricket in these circumstances without its existence in culture? What is this culture without the existence of the crickets?)

If the crickets appear to tire, if they hang back, losing interest in confrontation, or if one turns away, dejected, the referee will lower the gate to separate the fighters, reset the sixty-second timer, and invite the trainers to minister to their prospects. Like corner men at a boxing match, they work away to restore their charges’ fighting spirit, using different brushstrokes now, testing their technique. But often, like a boxer after a heavy pummeling, the cricket will simply slump, through loss of spirit or other injury, while his opponent will puff up and sing, and the referee will call an end to the fight. Then, all at once, the hubbub in the casino restarts with a rush, and cash again begins to fly—large notes to the winners, 5 percent in small bills coming back to the referee.

And the crickets? The winner is returned carefully to his pot, ready for the journey home or back into the public house to prepare for another fight. The loser, no matter how valiant, no matter how many of the Five Virtues he displayed, no matter that he is likely to be physically unscathed, has finished his career. The referee collects him in a net and drops him into a large plastic bucket behind the table, to be released “into nature” everyone tells me, to which Michael adds that it’s okay, I shouldn’t worry, he’ll be all right: the curse on anyone who harms a defeated cricket guarantees it.

5.

As the happy times approach their November climax, the phalanx of pots creeps further along the table and the contests stretch deeper into the night. But that evening of our first visit to Boss Xun’s casino was in late September, and there were just a handful of fights. After they were over, Boss Xun asked if we wanted to see the public house.

The public house is designed to counter some of the more underhand tactics said to be popular among cricket trainers. Of these, the most sensational is doping, especially with ecstasy, the head-shaking drug of Shanghai’s teen dance clubs.15 As anyone who’s taken ecstasy can imagine, a high cricket is likely to be a winning cricket. However, it might not be the rush of energy and confidence or the elevated sense of personal charm, attractiveness, and well-being that assures victory. In this type of doping, the real target is the opposition. Crickets are acutely sensitive to stimulants (hence the no-smoking, no-scent rule). They rapidly detect when their adversary is chemically enhanced, and they respond instantly (and no doubt sensibly) by turning tail, forfeiting the contest.

We left the casino and drove through downtown streets lined with new trees gleaming synthetically under fluorescent light, past sleeping factories and darkened office buildings, along wide, empty boulevards, past bright restaurants, dazzling neon karaoke palaces, late-night stalls selling vegetables, DVDs, and hot food, past the round-the-clock construction I’d so quickly grown to expect, along partly paved side streets, beside what could have been a canal, drawing up at another faded apartment building, ducking in through another anonymous door.

I enjoyed the feeling of anticipation as the car slipped through the quiet streets. My mind drifted to the discussion earlier that day in the golden banquet room at the Luxurious Garden between Boss Yang and Mr. Tung, the gambler from Nanjing, about what makes a successful casino. Mr. Tung had traveled from Nanjing to escape his circle—it was too small and too professional, he said; the crickets were too strong and the competition too fierce. Here in Minhang, he told Boss Yang with no sign of awkwardness, his chances of winning were greater, greater too than if he would go to downtown Shanghai.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mr. Tung’s perfect casino would be a place of comfort as well as security, a place with an appealing atmosphere. He conjured an image of expansive largesse, a scene peopled by relaxed and prosperous gamblers, frank and open, not the kind of men who would argue over small change. He seemed to be casting himself as Chow Yun-Fat in Wong Jing’s classic God of Gamblers or as Tony Leung in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai—or maybe that was my gambling fantasy, not his. He said: The crucial thing is connection; you should be cultivating the successful gamblers, encouraging them to bring more and more of their associates.

Boss Yang and Boss Xun’s casino attracted gamblers from Hong Kong, Zhejiang, and elsewhere, as well as from Nanjing. However, the two men were not focused on pampering their clients. There were reasons to keep the atmosphere congenial—an argument could lead to a killing and make the police feel that they had to put on a show—but, Boss Yang countered, the surest route to a successful business was through a reputation for fairness. The most important quality of a casino was the trust between the sponsor and his clients. Owners, trainers, and gamblers (often the same people) should feel safe and should be confident that their animals were safe too.

The public house was an impressive place, part maximum-security zone, part clinic. Every cricket slated for Boss Xun’s casino spent at least five days undergoing prophylactic detox here. There are thousands of such houses throughout Shanghai, he tells us, and he’s run one for many years, though of course in a variety of locations. It’s no game. The risk is large, increased tonight by the novelty of bringing me here. Several sponsors had been arrested and some executed in the anti-gambling drive that swept Shanghai the year before, and as we talk, Boss Xun’s right leg stutters rhythmically.

The public house is a four-room apartment stripped and retooled. Three rooms have multiply padlocked steel gates; the fourth is a social space equipped with couch, chairs, TV, and PlayStation, its whitewashed walls decorated with color close-ups of crickets, glamour shots. Nobody drinks or smokes. Two of the gated rooms are caged storage areas lined with shelves, on which I make out stacks of cricket pots. The third has been unlocked, and like the casino, it is brightly lit. Boss Xun leads us inside, and I see a long table and a row of men—owners and trainers here to care for their insects—each tending to a pot. Two assistants, men I recognize from the casino, are stationed across the table. One of them fetches the labeled pots from a cabinet behind him while the other closely observes the visitors. But what makes the scene genuinely startling and momentarily disorienting, even surreal, is that the men lined up at the table, silently intent on their crickets, are dressed identically in white surgical gowns and matching white masks.

Biosecurity is everything. Trainers in the public house give animals only the food and water provided on the premises, and in the casino use only those implements provided by the sponsor. It is well known that trainers dip their yard grass in solutions of ginseng and other substances, which, like smelling salts in a boxing corner, can revive even the most battered fighter. It’s well known that they try to contaminate the food and water of their competitors’ animals, that they try to engulf them in poisonous gas. It’s well known that they’ll insert tiny knives into their own yard grass and put poison on their fingertips in the hope of getting close enough to touch the opposition.

Nonetheless, the public house isn’t foolproof. One chink in the armor is the moment the insects first enter, when they’re fed and then weighed on an electronic scale. The weight is recorded on the side of the pot, along with the date and the owner’s name, and it then becomes the basis on which to assign the insects to fighting pairs. Great care is taken to match crickets as precisely as possible, to make the fights as even as possible, an effort that is institutionalized in the system of raising equal stakes on both animals at the start of a fight. Weights are recorded in zhen, a Shanghainese cricket-specific measure now used nationally. One zhen is around a fifth of a gram, and there must be no more than two tenths of a zhen difference between paired fighters. Recognizing an opportunity, trainers have become adept at manipulating their insects’ weight. In the past, they would subject the animals to an extended sauna to extract liquid just before the weigh-in. Nowadays, it’s more common to use dehydration drugs, which are impossible to detect and, by all accounts, produce few ill effects. Once fed, weighed, and admitted, the animal has at least five days under the care of the public-house staff and his visiting trainer to recover his strength, and if all goes to plan, he’ll ultimately fight below his weight—imagine Mike Tyson versus Sugar Ray Leonard!

It wasn’t long before we were back in Boss Xun’s casino, once more in seats of honor and once more in the grip of the crickets. Again I was impressed by the professionalism of it all. From the secured metal trunk carried in by the public-house assistants to the quickness of the referee and Boss Xun’s own congenial working of the crowd, this was a smoothly run operation. We caught the last train back to the city, and I again recalled the lunchtime discussion between Boss Yang and Mr. Tung. Boss Yang had stuck tenaciously to his view that nothing was more important than the casino’s reputation for fairness, and now I understood why. After all, only the sponsor and his staff had unsupervised access to the animals. With little difficulty, they could influence the contest in various hard-to-detect ways: by hiring a partisan referee, by matching the fighters unevenly, by neglecting to care for particular individuals adequately or by lavishing extra care on favorites (including their own—Boss Xun liked to fight his crickets here too). I remembered Boss Yang’s vigorous defense of his staff in response to Mr. Wu’s request to bypass the public house, and I saw that of course there must be no exceptions. Without full confidence in the sponsor’s probity and in his ability to create an environment safe from violence, corruption, and the police, there could be no circle, no event, no gambling, no profit, no entertainment, no culture.

6.

Dr. Li Shijun of Shanghai Jiao Tong University invited us to his home. A few journalists, some cricket experts, and a university colleague or two would also be there. We must be sure to show up as planned.

I was keen to meet Dr. Li. I’d seen him interviewed on a TV program included on a DVD I’d picked up on Anguo Road. The reporter was enthusiastic about the professor’s campaign to promote cricket fighting as a high-culture activity free of gambling. “Gambling,” she said in the final voice-over, “has ruined the reputation of cricket fighting. Cricket fighting is like Beijing opera; it is the quintessence of our country. Many foreigners regard it as the most typically Oriental element of our culture. We should lead it to a healthy road.” Just a few days before I arrived in Shanghai, Dr. Li had again featured prominently in the media, this time in a newspaper article about a gambling-free tournament he had staged downtown. The newspaper journalist identified Dr. Li as the “cricket professor.” The TV reporter had called him the “venerable cricket master.”

Dr. Li’s apartment was tucked away in a corner of a low-rise housing complex close to the university campus. He was a charming host, warm and welcoming, a youthful sixty-four-year-old, his lively features crowned with what I can only describe as a mane of silver hair. Several people were already there when we arrived, and he swiftly corralled us all in his office, all the while pointing out the prizes from his lifelong passion: the cricket-themed paintings, poems, and calligraphy created by him and his friends that enlivened the walls and bookcases, the large collection of southern cricket pots, which are the focus of one of his four published books on cricket-related matters.16

The professor ushered us into a large sitting room, in which he had laid out a variety of pots and implements. Selecting two pots, he carried them over to a low coffee table positioned in front of a couch. He transferred the crickets to an arena on the table and invited me to sit beside him. He put a yard grass straw in my hand and, as people often did, encouraged me to stimulate the insects’ jaws. I was clumsy with the brush and always felt as if I were tormenting the insect, which more often than not simply stood still and suffered my attentions. But I obliged and was jiggling my wrist as best I could when I looked up to find that all the other people present, with the exception of Dr. Li, who continued to stare intently at the crickets as if he and I were alone in the room, had somehow, from somewhere, produced digital cameras and were lined up in formation, snapping away at close range like paparazzi at a premiere. Michael too! And now Dr. Li turned creative director, instructing me how to position the grass, how to hold my head, what to look at, how to sit …

Maybe I’m unusually dense about this kind of thing, perhaps insufficently entrepreneurial. It was only later, on the crowded bus back to the metro with Michael and Li Jun, a smart young reporter whom Dr. Li had invited to join us for lunch, chattering away about my research and my impressions of Shanghai, that it dawned on me what was going on. Even Michael, who, it seems, had merely wanted to capture the moment, was startled by my naïveté.

A few days later, under the headline “Anthropologist Studying Human-Insect Relations, U.S. Professor Wants to Publish a Book on Crickets,” Li Jun’s article appeared in the mass-circulation Shanghai Evening Post. The photo caption, adapting a well-known saying, read “United by their love of crickets, these two strangers immediately became friends.”17

Li Jun subtly traced Dr. Li’s erudition. She noted his eager recourse to the yellowing books on his shelves, his willingness to take me on as his acolyte as well as his friend. (“Questions flew out of his mouth like bullets,” she wrote of my reaction to the crickets.) She identified Dr. Li as one of Shanghai’s modern literati, a person of refinement cultivating a set of scholarly arts, among which the contemplation, appreciation, and manipulation of what I would call nature—and which includes the judging, training, and fighting of crickets—have long figured prominently.18 In offering me guidance, she wrote, Dr. Li was chuandao jie huo, a Confucian term for the teacher’s task of passing on the knowledge of the ancient sages and resolving its interpretive difficulties. She let her readers know that his pro-cricket, anti-gambling campaign was a matter of culture, that it reached out from the whirlpool of the present to a higher ground that was both an available safe haven of the past and an anchor for the future. And she was right to do so, because without pointing to those capacities and desires, the rest didn’t make sense.

Dr. Li grew up in Shanghai, and like other men of his generation whom I met, his early fascination with crickets had been sparked and nurtured by an older brother. He describes passing the large (now long-gone) cricket market at Cheng Huang Miao every day on his way to school in the late 1940s; he remembers using his pocket money to buy crickets; he fondly recalls the circle of insect friends (chong you) that grew around him, boys his own age and, from time to time, the adults who would stop to play with them.

At twenty, he graduated from the Shanghai Film Academy and was assigned to the Shanghai Science and Education Film Studio, where he developed his skills as a cameraman and animator. In the mid-1980s, he was appointed professor of photography and animation arts at Jiao Tong University.

We didn’t talk about this, and he doesn’t discuss it in his writing, but the history of Shanghai during this period is well known: the falling out of favor of the cosmopolitan city that had given birth to the Chinese Communist Party; the never-implemented plan to dismantle the metropolis and disperse a population rendered suspect by the city’s decadent colonial past; the forced closure of hundreds of its factories, schools, and hospitals and the relocation of 2 million of its residents during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution; the city’s precipitous decline and stagnation until its belated incorporation into Deng’s reform strategy with the Pudong policy of 1992; its spectacular return to eclipse Hong Kong, looking out across the East China Sea not only toward the West but toward Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia.19

And all the while, Li Shijun cultivated his passion for crickets. He married, raised a family, carried out his responsibilities, advanced his career, expanded his cricket-loving circle, and refused to gamble. He told the story of how he would wander his Shanghai neighborhood seeking a cricket partner, someone willing to pit his insect against his own, but to do so without staking money. Time after time he was rebuffed. He offered to fight simply “for exercise,” just for practice, but no one would place his animal at risk without potential reward. He returned home dejected, embittered by the “poor condition of the world around him.” It was then that his wife, seeing his distress, made herself his special chong you, and there, alone in their apartment, together they fought crickets.20

This was the early 1980s, as the restless wake of the Cultural Revolution gave way to the new turbulence of reform. Cricket fighting was already experiencing the stirrings of a revival that would bring teams of enthusiasts from Jiao Tong and Fudan universities for intervarsity competitions at Dr. Li’s apartment, where his wife and daughter would prepare lavish banquets (as they did for Michael and me) and nurture a sort of cricket salon under the professor’s patronage and sponsorship, a salon of real friends, he wrote, not the kind of friends one makes through gambling, who fall out over money and become strangers forever. Unlike those gamblers who travel together, collect together, fight together, but keep their own knowledge secret from one another, these cricket lovers share their experience. They are a circle of constant friends united by their love for crickets, a circle of men among whom he is the acknowledged big brother.

I can’t shake Dr. Li’s image of himself and his wife in their Shanghai apartment, refugees from the deterioration they sensed all around them yet on the cusp of a florescence in the activity they love, which is fueled not by a return to the elite traditions of cricket culture he values so highly but by a relaxing of moral codes and a rising tide of both surplus income and financial desperation, a rich matrix for the regeneration of gambling, the source of so much of Dr. Li’s anxiety. And this is all deeply ironic for the professor, as well as disturbing and perhaps disorienting, because for Li Shijun the care and combat of crickets is a matter of yi qing yue xing, which corresponds to something like the cultivation of moral character, the elevation of one’s self and, by extension, of society as a whole.

Both in person and in his writings, the professor is direct. At the end of his book Fifty Taboos of Cricket Collecting (don’t buy a cricket whose jaws are shaped like the character ![]() , don’t buy a cricket with rounded wings, don’t buy a cricket with just one antenna, don’t buy a cricket that is half-male, half-female, and so on), he remarks that it is no mystery that society looks down on cricket fighting. Whereas at the university he teaches in a suit and tie, at the insect market, surrounded by “low-level people,” he is compelled—for fear of appearing ridiculous—to wear slippers, T-shirt, and shorts like everyone else. The lack of cultivation—evident in the smoking, cursing, and spitting all around him—is not simply a personal matter: “If you want others to treat you with respect you must first act decently,” he insists.21

, don’t buy a cricket with rounded wings, don’t buy a cricket with just one antenna, don’t buy a cricket that is half-male, half-female, and so on), he remarks that it is no mystery that society looks down on cricket fighting. Whereas at the university he teaches in a suit and tie, at the insect market, surrounded by “low-level people,” he is compelled—for fear of appearing ridiculous—to wear slippers, T-shirt, and shorts like everyone else. The lack of cultivation—evident in the smoking, cursing, and spitting all around him—is not simply a personal matter: “If you want others to treat you with respect you must first act decently,” he insists.21

Nor is it merely a question of deportment. The circle he is creating is both a refuge and an example. There is, he says, a crisis of civility in Chinese society, and cricket fighting, with its long history as a cultivated art, is a discipline, a spiritual road, the ideal vehicle for the cultivation and elevation of the self. With its traditions, knowledge, and scholarly demands, cricket fighting is a rare practice, more akin to tai chi than mahjong. But it is a practice debased by gambling. How nightmarish that an activity so elevated has become the vehicle of such degeneration.

Campaigns against gambling have been a feature of the People’s Republic since the liberation. But despite periodically aggressive policing and especially since the post-Mao reforms, the party has had little success in controlling its expansion. Unlike the attempt to outlaw mahjong, which failed during the 1980s, the assault on crickets has been indirect, paralleling policy during the Ming and Qing dynasties, when imperial prohibitions ran up against the emerging professional network of urban cricket houses and legislation targeted gambling rather than crickets.22