The Illustrated Insectopedia - Hugh Raffles (2010)

Yearnings

1.

Kawasaki Mitsuya sells live beetles on the Internet. My friend Shiho Satsuka found his site and, knowing it would get my attention, sent me the link. A few weeks later, I was in the suburbs of Wakayama City, outside Osaka, with my friend CJ Suzuki, sitting in Kawasaki’s insect-filled living room and talking about ookuwagata, the Japanese stag beetles in which he trades.

Kawasaki Mitsuya recently gave up his job as a hospital radiographer, but there’s no money in stag beetles, he tells us. He opens some jars and explains that he does this for love. He fills his website with his poems. Some are silly, some are cute, some are abruptly bitter, even angry. Most are melancholy laments that contrast middle-aged male disillusion with the innocent openness of youth. (“He looks at the sky and the blue stays in his eyes. / The eyes of a child are like glass balls that truthfully reflect the world. / The eyes of the grown man have lost their light, / His eyes are cloudy like stagnant pools.”)1

Kawasaki tells us that his mission is to heal the family. He wants to open the hearts of men and bring them closer to their sons. Fathers have become cold; their hearts are hard and dry. Their lives are deadening. They have no interest in their children. They don’t feel the connection. On his website, he offers to lend stag beetles at no charge. Perhaps insect friends will bring families together. He remembers the love he felt when he was a boy hunting beetles in the mountains around Wakayama. “I want to nourish their hearts,” he says.

Online, Kawasaki Mitsuya calls himself Kuwachan, a sweet name that a parent might give a child who is fond of insects: kuwa from kuwagata, or stag beetle, and -chan a common diminutive suffix. Across the top of his home page is a brightly colored cartoon of a small boy in full insect-collecting kit. It is Kuwachan as he remembers himself in the 1970s, white hat, hiking boots, water canteen and collecting box slung around his neck, a butterfly net grasped like a flag in the breeze, its pole thrust into the earth. Kuwachan the insect-boy, high on a hill, back to the viewer, face upturned to the blue of the sky, arms thrown wide to the world and its possibilities.

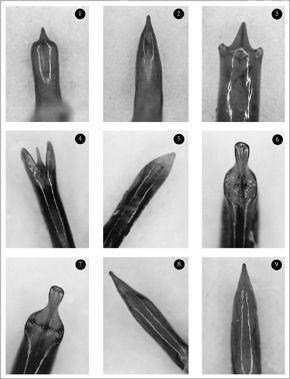

A few days earlier, CJ and I had spent the day in Hakone, a popular spa town in the hills southwest of Tokyo. We were visiting Yoro Takeshi, neuroanatomist, best-selling social commentator, and insect collector. Like Kuwachan, Yoro welcomed us into his home and filled the day with wide-ranging conversation. Yoro is in his late sixties, but he pursues his insects with youthful energy, augmenting his enormous collection with expeditions to Bhutan, chasing weevils as well as the more extravagant elephant beetles. When CJ and I arrived at his house, he was examining a set of burnt-orange penises from type specimens on loan from the Natural History Museum in London, using his state-of-the-art microscopes and monitors to reveal species-defining morphological differences that made me wonder about human limitations that had never previously crossed my mind.

Like Kuwachan, Yoro has loved insects since he was a child. Like Kuwachan, he told us that they affected him profoundly. After collecting for so many years, he now has “mushi eyes,” bug eyes, and sees everything in nature from an insect’s point of view. Each tree is its own world, each leaf is different. Insects taught him that general nouns like insects, trees, leaves, and especially nature destroy our sensitivity to detail. They make us conceptually as well as physically violent. “Oh, an insect,” we say, seeing only the category, not the being itself.

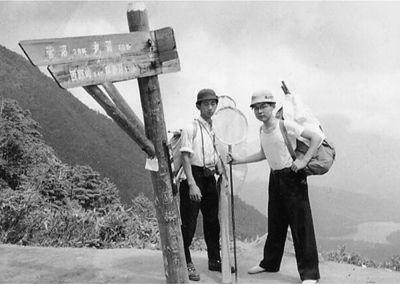

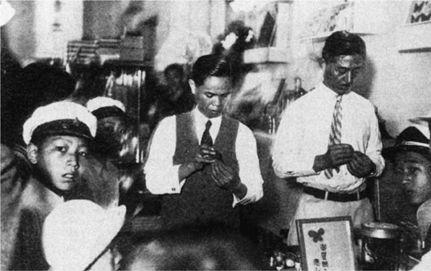

Shortly after returning to Tokyo, CJ and I came across this photograph, evidence that Yoro, like Kuwachan, was once an insect-boy, a konchu-shonen. There he is on the right, resolutely setting off into the hills of Kamakura soon after the Second World War, a time of devastation and hunger, but a time nonetheless of adolescent exploration and freedom.

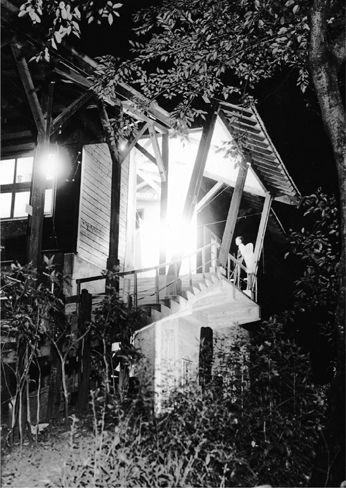

We met Yoro at his newly built weekend home, a quirky barnlike construction designed by the “Surrealist architect” Fujimori Terunobu that—with its strip of meadow sprouting from the apex of the roof—suggests both Anne of Green Gables and The Jetsons. The house reminded us of those out-of-joint structures that populate Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, and other epic animations by Hayao Miyazaki, structures that fill an elaborate universe that is somewhere and some when unknown but still somehow instantly familiar.

The connections were not accidental. It emerged that not only are Yoro Takeshi and Hayao Miyazaki close friends but that Miyazaki, too, cultivates a passion for insects that began with a childhood as a konchu-shonen. What’s more, it seems Miyazaki also enjoys collaborating with avant-garde architects. He and the artist-architect Arakawa Shusaku have drawn up plans for a utopian town whose houses are not unlike the one in Hakone to which Yoro gets away from the city and in which he keeps his insects. Theirs is a distinctly hippie vision of social engineering, motivated by some of the same worries about alienation and some of the same yearnings for community that preoccupy Kuwachan. Theirs is a town where children can escape what all of these men see as the profound estrangement of Japan’s media-saturated society and where they can rediscover a golden childhood of play, experimentation, and exploration in nature, where children—and adults too—can learn (again) to see, feel, and develop their senses.2

Kawasaki, Yoro, and Miyazaki were only the first of many insect boys that CJ and I encountered in Japan. It seemed that wherever we went, we met konchu-shonen, both large and small. We came across a famous one in Takarazuka, the home of the celebrated all-women theater company, with its long-lasting idols and mass following of devoted female fans. We couldn’t get tickets to a performance, but no matter. We were in town for another attraction, the Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum, a perfect small museum dedicated to the life and work of the acknowledged god of manga (and innovator in anime), who died in 1989.

If Miyazaki is the current superstar of anime, Tezuka was the artistic genius who used the narrative techniques of cinema to transform the printed page, creating a dizzyingly kinetic comic-book form that accommodates every conceivable subject matter and emotion. He, too, was a passionate insect collector, so passionate that he named his first company Mushi Productions, incorporated a cute version of the Sino-Japanese character for the word mushi into his signature, and populated his stories with butterfly-people, erotic moths, beetle robots, and endlessly varied metamorphoses and rebirths. Sure enough, there was Tezuka fully decked out as Insect Boy in the museum’s introductory video, ready for adventure, an early intimation of Astro Boy, the android superhero who is still one of Tezuka’s most marketable creations (and who, in the intricate, multiauthored ways of such creativity was, Tezuka recalled, inspired by Walt Disney’s Jiminy Cricket—a different kind of insect-human).

“This place was a space station, a secret jungle for explorers to discover,” Tezuka’s text reads; in the background melodic harpsichords and the chirps of birds and crickets. It was “an infinity where imagination could expand forever.” The sky is a dreamlike azure; the boys are in sepia. As the images floated by, CJ translated: “I was bullied as a child and thrust into war. I cannot say everything was great, and I don’t want to dwell in the past. But looking back now, I’m grateful to have been surrounded by so much nature. My experience of running freely in mountains, rivers, and meadows and of the insect collecting in which I was so absorbed gave me unforgettable memories and imbued in me a feeling of nostalgia as a deep part of my body and my heart.”

Tezuka won’t dwell in the past, but he won’t give up that longing either, the sweet-sad pleasure that feeds on the impossibility of erasing the distance between me then and me now. It’s an absence easy to reproduce: easy as an azure sky and two sepia boys. It’s an absence easy to fill, too, if not with a mail-order kuwagata then with an afternoon spent mushi hunting.

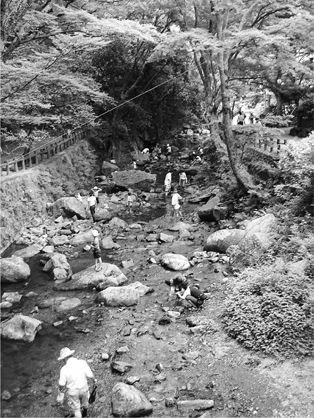

CJ and I shade our eyes as we step out of the insect museum in Minoo Park, the same park where Tezuka the konchu-shonen first collected insects with his sepia friends. Here, all around us, under the bluest sky, are living families, here in the here and now, fathers and sons (and a few women and girls also, although they rarely show up in the memories or longings of konchu-shonen). Here they are in the bright afternoon sun, fully equipped konchu-shonen, spread out along the shallow river, searching for bugs—water striders, water boatmen, crabs, too—serious but happy, balanced on rocks, dipping toes into the cool water, splashing around, emptying nets, showing their grown-ups what they’ve found (not much, as it’s too early in the summer).

The children are collecting specimens for their school summer projects, and their fathers are there to help them, also in shorts and hats, also holding the nets and buckets, which they got for ¥2,000 (U.S.$20), a price that includes a lab session at which anything they find can be pinned, ID’d according to the full-color zukan (field guide), and turned into a specimen. It’s a sunny day of kazoku service, family service. A day to fulfill the promise of Kuwachan’s poems, a day for boys to use their nets to catch the memories for a lifetime and men to learn again how to be fathers as they relive what it felt like to be a son.

And speaking of fathers and sons, here is one more insect-boy. He’s standing with the inflatable rhinoceros beetle that his father just bought for him at the summer festival. They’re on their way home, late at night outside the Minowa metro station in northeast Tokyo, a boy and his father under the streetlights, stopping to chat with a stranger and pose for a photo.

That’s just camera shake during a long exposure. But it’s as if he’s hardly there. The little boy with his giant kabutomushi. He’s melting into the lights, already inaccessible, already an object of desire, longing, and regret.

2.

CJ and I were here in Japan to find out about the two-decade-old craze for breeding, raising, and keeping stag beetles and rhinoceros beetles. We’d prepared in the usual way: by spending too much time Googling Japanese insect sites (of which there are many) and by talking to friends and reading the books and articles they recommended. By the time we met up in Tokyo, we knew that as well as generating widespread excitement, these big, shiny beetles so reminiscent of the chunky Japanese robot toys that swept the United States in the mid-1980s were also creating considerable anxiety among ecologists and conservationists and in Japan’s venerable insect-collecting community.

But what we hadn’t realized was the extent to which this beetle boom was part of a much larger phenomenon. Those konchu-shonen were a symptom. In our three weeks traveling in Tokyo and the Kansai region around Osaka, both of us were openmouthed at the abundance and diversity of human-insect life. Returning to Tokyo after four years in California, CJ—my research friend, translator, and up-for-anything traveling companion—confessed that although he must have lived most of his life in the midst of this insect world, he’d never really seen it before.

Because insects were everywhere! It was insect culture, something I’d never imagined. Insects had infiltrated a vast swath of everyday life. CJ and I pored over super-glossy hobby magazines with their beetle glamour spreads, spoof advice columns, and colorful accounts of exotic collecting expeditions. We studied pocket-size exhibitions and read xeroxed newsletters from suburban insect-lovers’ clubs. We visited the geek-tech-culture otaku stalls in Akihabara, Tokyo’s Electric City, and found pricey plastic beetles on sale alongside maid and Lolita fetish figurines. We ducked under low-hanging subway-car posters for MushiKing, Sega’s warring-beetle trading-card and videogame phenomenon, and we watched kids battling one another with controlled intensity at the MushiKing consoles in city-center department stores. We bought soft drinks in convenience stores hoping for the free Fabre collectibles that came with them. We explored some of the scores of insectaria throughout the country and gaped at the glass-and-steel grandeur of the butterfly houses, monuments of the 1990s’ bubble economy but also testament to a popular passion. We sat in smoke-filled coffee shops and on air-conditioned bullet trains reading the insect-themed serials in the biweekly mass-circulation manga anthologies (Insectival Crime Investigator Fabre, Professor Osamushi), a legacy not only of Tezuka’s insect obsession but also of other manga pioneers, including Leiji Matsumoto, famous for his hyper-detailed drawings of future technology (cities, spaceships, robots—insects made metal). We YouTubed Kuwagata Tsumami, a cartoon for young kids about the super-cute mixed-species daughter of a kuwagata father and a human mother (don’t ask!). We visited the country’s oldest entomological store, Shiga Konchu Fukyu-sha, in Shibuya, Tokyo, which sells professional collecting equipment of its own design—collapsible butterfly nets, handcrafted wooden specimen boxes—of a quality to rival any in the world. We read about (but couldn’t get to) the officially designated hotaru (firefly) towns, whose residents strive to capture the charisma of bioluminescence, to build a local tourist trade, and to pull in conservation funding as riverine habitats decline and firefly populations dwindle. (And, if we forgot the allure of the firefly, we were reminded every evening by the strains of “Hotaru no Hikari,” “The Light of Fireflies,” broadcast at closing time in stores and museums, a song about a poor fourth-century Chinese scholar studying by the light of a bag of fireflies, a song that every Japanese person seems to know, set to a tune—“Auld Lang Syne”—that every British person knows too.)

Of course, we took any opportunity we could to talk to people in the neighborhood insect pet stores, which were packed to the rafters with live kuwagata and kabutomushi in Perspex boxes and with the numerous products marketed for their care (dry food, supplements, mattresses, medicine, and so on), often in cute kawaii packaging depicting funny little bugs with big, emotion-filled eyes acting out in funny little poses. And we also saw the much sadder boxes in department stores crammed with too many too-agitated big beetles and skinny suzumushi bell crickets, all on sale at rock-bottom prices. One late night we stumbled upon a display of live beetles in a glass box in the lobby of a suburban train station, an encounter made surreal by the silence of the hour, the insistent sound of the animals’ scratching, and the realization that they, we, and the battering moths were the only living beings on hand. Should we liberate them? We wanted to visit a mushiokuri festival to see how the driving out of the insects from the rice paddies—banned by the Meiji government in the early twentieth century as anti-scientific superstition—was being revived as a rural tradition in an ever-urbanizing, ever-reflective nation, but the closest event (at Iwami, overlooking the Sea of Japan in Shimane Prefecture) was just too far, given everything else we were cramming in, and the mushiokuri became another of those items we failed to cross off our to-do list.

Knowing our interests, everyone was keen to tell us about Japanese insect love. Look around you! Where else are fireflies, dragonflies, crickets, and beetles so esteemed? Did you know that the ancient name for Japan, Akitsu-shima, means “Dragonfly Island”? Have you heard “Aka Tombo,” the Red Dragonfly song? Did you know that in the Edo period, the time of the Tokugawa shogunate, people would visit certain special places (Ochanomizu, in downtown Tokyo, was one) just to bask in the songs of their crickets or the lights of their fireflies? Did you read the classical literature? The eighth-century Man’yo-shu has seven poems about singing insects. The great classics of the Heian period, the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon and Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji contain butterflies, fireflies, mayflies, and crickets. Crickets are a symbol of autumn. Their songs are inseparable from the melancholy of life’s transience. Cicadas are a sound of summer. Do you know haiku? Basho wrote, “The silence; / The voice of the cicadas / penetrates the rocks.”3 Do you know “The Lady Who Loved Worms”? She was the world’s first entomologist. A twelfth-century entomologist! You know she was the inspiration for Miyazaki’s famous Princess Nausicaä? Do you know Kawabata Yasunari’s beautiful story of the grasshopper and the bell cricket? It’s just a wisp of memory held together by two tiny insects. Have you read Koizumi Yakumo’s writings on Japanese insects? Maybe you know him as Lafcadio Hearn? He had a British father but worked in America as a journalist. He became a Japanese citizen and died here in 1904. In his famous essay on cicadas, he wrote, “The Wisdom of the East hears all things. And he that obtains it will hear the speech of insects.”4 (And a few days later, over coffee in downtown Tokyo, Okumoto Daizaburo, literature professor, insect collector, and Fabre promoter, paraphrases his own book and rather sourly, though perhaps not unfairly, says of Hearn, the unashamed Japanophile and Orientalist who was also the translator of the definitive version of Flaubert’s Temptation of Saint Anthony, “No one can find in others what they lack in themselves.”) Please go to Nara! You must visit the Tamamushi-no-zushi shrine in the ancient Horyuji Temple. It was constructed in the sixth century from 9,000 scarab beetle carapaces!

These last suggestions came from Sugiura Tetsuya, an erudite and energetic docent volunteering at the Kashihara City Insectarium not far from Nara and its many ancient temples. In his younger days, Sugiura told us, he collected butterflies in Nepal and Brazil. Recently, he had donated his specimens to the insectarium in which he worked, where, as he pointed out, he was able to see them whenever he wished. He would, he said, have preferred to send them to a bigger and better-attended facility, like one of the Tokyo zoos—Ueno or, more likely, Tama, with its huge butterfly-shaped insectarium—but neither, disappointingly, had the capacity to accept donations.

It turned out it was Sugiura Tetsuya himself who had suggested the insect museum and butterfly house to the mayor of Kashihara when the plan for an aquarium turned out too expensive. He was kind enough to spend the entire afternoon explaining the museum’s extensive collection to us and later sent a package to me in New York with a selection of Hearn’s insect writings along with articles on many ancient items of interest, including one describing an elaborate insect box and other objects finished with lac—the resinous secretion of scale insects—that had been placed in the Shosoin, the Imperial Repository, near the Todaiji Temple in Nara in A.D. 756 and immaculately preserved to this day.

In the final room of the museum, after our exhaustive tour, Sugiura-san stopped at a case documenting the insect cuisine of Thailand and told us how Japanese visitors, schoolchildren especially, are disgusted by this display and how they exclaim over the primitive habits of the Thais. I remember quite clearly, he continued with no change of expression, how I used to go into the mountains with my classmates after the war to collect locusts, which we would bring back to school and boil with shoyu. We also ate boiled silkworm larvae in those days, he said, and stopped only when the silk industry declined in the 1960s and the supply of insects dried up. It was hard-times food, but it was good food. It was part of our cuisine, but you would never know that now. It was the culture of the popular classes, he said, a culture rarely recorded and always forgotten.

3.

Sugiura Tetsuya had his doubts about the fashion for kuwagata and kabutomushi. He was happy to see so many children and families coming to Kashihara; he knew their enthusiasm was sparked by pet beetles and the runaway success of MushiKing, and he didn’t want to discourage them. But like most collectors and insectarium people we met, he was anxious. Yes, he agreed, the excitement over stag beetles and rhinoceros beetles was an expression of (and a stimulus to) the national enthusiasm for insects. But it brought problems all its own.

Nearby, at the Itami City Insectarium in Hyogo Prefecture, CJ and I stumbled onto an “insect carnival.” Upstairs in the nature-study library, a crowd of high-spirited children and adults was creating some impressively complicated insect origami. We stopped at the “Befriend a Cockroach” table to learn how to handle the large live animals (stroke their backs gently, then pick them up carefully between thumb and forefinger and set them in your palm). All around, the walls were papered with exhibits by local insect-lovers’ clubs: spreads from their newsletters, illustrated reports of environmental challenges met and often overcome, photos from field trips that showed smiling club members (varied in their ages but united in their enthusiasm).

Downstairs, the staff had given pride of place to kuwagata and kabutomushi. But they had also set free their psychedelic imagination. CJ read off the titles from the cases: “Wonderful Insects of the World,” “Strange Insects of the World,” “Beautiful Insects of the World,” “Ninja Insects of the World.” And across the room, “Surprising Insects of the Kansai Region.” The Beautiful Insects formed an intricate mandala; the Ninja Insects (characterized by skillful camouflage) disguised themselves as a tiki mask; in one display, two tiny leaf bugs were dressed up in paper kimonos; in another, a host of gorgeous blue morpho butterflies floated between glass, spotlit to magnify their irridescence. Hard not to love this place, we agreed. Part science center, part art museum, part amusement park. A place to celebrate our inner insect.

Just before “Hotaru no Hikari” rang out for closing time, we bumped into a museum guide and a curator in the hallway. They talked the same language as Sugiura, found themselves caught in the same contradictions. The emphasis on the spectacular imported insects made them uneasy. But they felt compelled to promote those big foreign species even though they believed that doing so placed Japanese beetles in peril.

Some backstory is in order here. The right person to tell it is Iijima Kazuhiko, who works at Mushi-sha, the largest and best known of Tokyo’s many insect stores. Most of these are pet stores, overflowing with beetles and the paraphernalia needed to keep them. Most cater to elementary school boys, their indulgent (or perhaps long-suffering) mothers, and a smaller number of middle-aged men who buy the more expensive animals. Most of the stores have appeared since 1999, the year the current beetle boom really took off.

But Mushi-sha, Iijima Kazuhiko explained, doesn’t quite fit this profile. It reaches across two insect worlds, joining the preteen MushiKing fans to the scholarly collectors like Sugiura Tetsuya and Yoro Takeshi. Since it opened its doors, in 1971, the store has continually published Gekkan-mushi (Insect Monthly), a respected entomology journal, and has sold specimens, boxes, and collecting tools. In those early days, its customers were serious amateurs and professional entomologists, konchu-shonen old and young who were building collections primarily by catching their own insects.

It was in the 1980s that Mushi-sha began selling live animals. Back then, Iijima told us, it was ookuwagata, the large Japanese stag beetles that Kuwachan breeds, that were in demand. They had become difficult to find in urban areas but were still easily available in the countryside, and it was commonplace there for children to keep them as pets. Some stag beetles lived in the mountains, mostly in Osaka, Saga, and Yamanashi Prefectures. But most made their homes close to villages, in satoyama, the patches of forest that people managed for mushrooms, edible plants, timber, compost, and charcoal, among other useful goods.5 Over time, the burned and coppiced charcoal trees came to look like dark knobs, Iijima said, and it was in the holes in those trees that the kuwagata lived. Kuwagata were at home in satoyama, he told us, because they like being close to humans.

Iijima explained that the kuwagata and kabutomushi boom of the 1980s was stimulated by an increased supply of insects to the cities at a time of high disposable income, before the collapse of the bubble economy. Recognizing the signs of urban demand and developing more effective trapping techniques, villagers brought beetles to Tokyo from the countryside, selling them to department stores and pet shops. Some urban enthusiasts went the other way, deepening their hobby by traveling to the country to catch beetles themselves (and plant the seeds of the informal network of rural inns that now advertise their services as beetle-hunting bases). Others became interested in breeding beetles. Both larvae and adult beetles were available to buy and hobbyists started investing their time in developing techniques for raising bigger animals. This shift to breeding was a significant innovation, said Iijima. Even though back then no one managed to raise beetles as large as the ones found in satoyama or the mountains, many people took up the challenge. Not surprisingly, it was in these years of growth—both in the economy and in the passion for beetles—that most of the country’s insectaria opened.

The real estate boom that swept Japan in those years transformed the countryside. As demand for charcoal fell and brick replaced timber in home construction, the maintenance of managed forest declined; as housing developments expanded, satoyama retreated. By the early 1990s, it was challenging even for local people to find large stag beetles in the wild. For most visitors from the city, it was far harder. Prices of wild insects soared. Yet by this point there was a thriving subculture of beetle breeders throughout the country—amateur experts like Kuwachan who succeeded in mapping the life cycles and habits of the popular species and in developing and circulating sophisticated yet easily replicated techniques for raising large animals from eggs.6

It was a complex story, but Iijima Kazuhiko was a patient narrator. Like everyone we met in Mushi-sha, he was young, friendly, knowledgeable about all aspects of the business, and serious about insects. We were standing at the back of the store, in front of a large, indexed cabinet full of high-quality specimens from around the world and beside tall stacks of Gekkan-mushi, Be-kuwa!, Kuwagata Magazine, and other glossy and expensive specialist publications. On all sides were shelves of Perspex containers holding male and female kuwagata and kabutomushi of varying sizes and prices. From behind the counter Iijima pulled out a large foam-lined case. Inside—huge, soft bodied, and defenseless, motionless on its back—was a metamorphosed beetle pupa. It was a male Dynastes hercules, the largest of the rhinoceros beetles, recorded as growing to just over seven inches, and worth well over U.S. $1,000. A small group of admiring customers gathered to look.

In the 1990s, continued Iijima after returning the case, there were three types of enthusiasts. There were those who went to the mountains to hunt beetles; they were working in the tradition of the old-time collectors, but it was, of course, much harder now for them to find insects. Then there were those, usually schoolboys, who purchased inexpensive live beetles and kept them as pets. Finally, there were those who bought larvae or adult pairs and bred them as a hobby or for sale, often trying to set the record for the largest individual of the particular species. Indeed, he said, by that point it was much easier to breed kuwagataand kabutomushi than to catch them.

Despite (and because of) the decline in wild beetles and the destruction of their habitat, beetle keeping and raising was thriving. Mushi-sha was at the center of a lively entrepreneurial culture serving both a new generation of insect fans and an aging but rejuvenated cadre of experts. When CJ and I met Okumoto Daizaburo a few days later, he readily took on the task of explaining why it was that all this insect love existed here in Japan. Professor Okumoto used arguments we had heard from other insect people, arguments that described a uniquely caring Japanese relationship with nature and drew on nihonjinron, the persistent ideology of Japanese exceptionalism, which, like many nationalisms, is based on a belief in a unified national population possessing a unique transhistorical essence.7

The beetle boom, Okumoto said, was just one piece of a special national affinity for nature. He talked about the high species endemism of the country’s island ecosytem and how this unusual variety of animals and plants, and of insects in particular, produced an exceptional sensitivity among the human population. He talked about earthquakes and typhoons and how these too-familiar events created a visceral awareness of the surrounding environment. He talked about the role of animism, Shintoism, and Buddhism in creating an intimate environmental ethic that still pervades Japanese daily life despite the decline in overt religious practice. He talked about the audiologist Tsunoda Tadanobu’s controversial research in the 1970s, which suggested that Japanese brains are singularly attuned to natural sounds, including cricket song.8He talked about the extraordinary expressions of high cultural attachment to insects in literature and painting. And borrowing my notebook, he drew a diagram—a schematic representation of an ideal Japanese life, which CJ later annotated for me.

It was an ideal man’s ideal life, timeless but classical, the ideal life of a scholar or nobleman. Professor Okumoto offered it as a sketch of enduring national tradition, an elegantly simple capsule of a complex ideology. He depicted three ages of man in an arc from youth to dotage, from carefree friends chasing dragonflies and goldfish to the sunset years of meditative solitude; he described how each stage has objects and activities appropriate to the correct forms of self-cultivation (from kabutomushi and fireflies through ka-cho-fu-getsu—flower-bird-wind-moon, the contemplation of the subtleties of nature—to the care of chrysanthemums); and he explained that these simple practices can (even in such an elementary version) create a meaningful Japanese life.

As the professor talked, it struck me and CJ that these forms of play, culture, and contemplation were an aspiration, a promise of contentment and fulfillment that tied together many of the insect people we had met. His sketch reminded us of the yearning for emotional purity at the heart of Kuwachan’s insect poems. It was a framing for the stories of insect love as a formative stage in the making of a whole person. Antithetical to urbanized, bureaucratized modern life, unattainable by most people even in childhood, as a model for a form of life, its role was largely critique. It was part of that family of utopian insect stories that included Miyazaki’s hippie town, Tezuka’s secret jungle, Kuwachan’s poetry, and those hopeful weekends of kazoku service. And, like those stories, it helped explain some of the emotional burden that Japanese insects were asked to assume and some of the desires that they seemed so readily to bear.

4.

Before 1999, most Japanese insect lovers knew foreign stag and rhinoceros beetles through magazines, television, and museums. These animals were often bigger and more spectacular than the local species; many had longer horns and antlers, larger bodies, and showier coloring. But under the Plant Protection Act of 1950, it was illegal for private collectors to bring them into Japan. There was, however, no penalty for owning or selling restricted animals once they were in the country, and that anomaly enabled a lively black market, extravagant prices, and a profitable smuggling industry reputedly controlled by the yakuza. Still, the number of animals involved was relatively small and the well-heeled collectors involved were a select set.

The Plant Protection Act compiles lists of animals considered “detrimental” to native plants and agriculture. However, it has an unusual precautionary protocol: all species are classed as detrimental until authorized for entry at a plant protection station. In 1999, under pressure from collectors eager to know which beetles were permitted, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries published a list on its website of 485 stag beetles and 53 rhinoceros beetles considered “nondetrimental.”9 Within two years, 900,000 live kuwagata and kabutomushi had been imported.10 Even so, in succeeding years the ministry added more species to its list until, by 2003, 505 species of stag beetle had been authorized out of a worldwide total of around 1,200 described species. As the entomologists Kouichi Goka, Hiroshi Kojima, and Kimiko Okabe commented drily, “The habitat maintaining the highest biodiversity of stag beetles is Japanese pet shops.”11 In 2004, they estimated the value of the import trade at ¥10 billion (about U.S.$100 million). Large individuals of desirable species were selling in Tokyo for upward of U.S.$3,300.12

The scale of the growth in live-insect imports was completely unexpected. Iijima Kazuhiko told us that the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries ignored warnings from the Ministry of the Environment but, nonetheless, the government had no idea what it was unleashing. However, he added, there were high-profile precedents that should have been cause for hesitation: animals such as the black bass, the raccoon, the small Indian mongoose, and the European bumblebee Bombus terrestris, which are infamous in Japan for adapting too successfully to their new environment. But when it came to beetles, policy makers and scientists were confident that foreign kuwagata and kabutomushi, most of which come from subtropical and tropical Southeast Asia and Central and South America, would be unable to survive the harsh Japanese winter. Only later did they realize that many of those animals’ home ranges were at high altitudes in cooler temperatures.13

The import boom crested quickly. By 2001, the number of beetles entering Japan had fallen significantly from its height, and as the supply increased, the prices for all but the rarest (and largest) slumped too.14But even with reduced quantities, it was evident that the boom had radically expanded the breadth of the trade. New insect shops had opened their doors, and existing pet stores had retooled. Large department stores were carrying imported species. For a while, live beetles were available from vending machines. All kinds of products that made raising and caring for the animals simpler and more appealing were brought to the market (individual servings of food in jelly form, “fungus jars” of habitat medium, deodorizing powders, cute carrying cases). Most significantly, an unknown but anecdotally vast number of people had taken up beetle breeding. Between 1997 and 2001, seven glossy specialist magazines were founded that offered advice to breeders, ran competitions, featured stories of intrepid collectors, shaped a sense of beetle aesthetics, and nurtured the emerging communities of enthusiasts.15

Struggling to account for the surging appeal of pet insects, the author of the insect section of the Japan External Trade Organization’s Marketing Guidebook for Major Imported Products for 2004 pointed out that beetles “require little time and energy to take care of. They do not need to be fed anywhere in particular, and their pens take up only a small amount of space on top of a desk…. [They] do not make noise and they do not have to be taken outdoors for exercise.”16 This seemed like an uncontroversial if superficial explanation, but the correlative claim that much of the market expansion was due to twenty-something urban women attracted to low-maintenance companion species was more dubious. Despite the apparent democratization of the hobby, despite the eager participation of some schoolgirls in summer insect projects, despite the success of insect-loving female role models such as Miyazaki’s Princess Nausicaä, and despite Sega’s girls-only MushiKing events, Iijima Kazuhiko—in line with other people CJ and I spoke to—estimated that even if the total number of female insect lovers was growing, only 1 in 100 of the enthusiasts who shopped at Mushi-sha were women, a proportion that had changed little over the years. Most of the women entering the store, he said, were chaperoning their sons. Instead, insect-loving women and girls were rare enough to warrant a satirical column in Be-kuwa! purportedly written by a beetle-crazy dominatrix-ish Sex and the City-ish girl-about-town (the continuing joke being the incongruity of the glamorous Ms. Shoko’s passion for insects).

Yet there was absolutely no question that the overall base was rapidly increasing. Professional insect specialists found themselves yearning for the calm old days. The stern price discipline reputedly enforced by the yakuza no longer seemed so grim. Stories circulated of families, tired of pet keeping or sorry for the animal cooped up in its plastic box, driving out of town and releasing their kuwagata in the woods. Reports surfaced of large caches of imported beetles discovered in the countryside: surplus stock abandoned by breeders and store owners who had fallen victim to too-rapid expansion. (“It’s only the people like me, who were in this for love rather than money, who have survived,” Kuwachan told us.)

More embarrassing, a series of high-profile cases involving the arrest of Japanese nationals caught smuggling quantities of prohibited beetles out of Taiwan, Australia, and various Southeast Asian countries revealed that the incentives and possibilities for trafficking had only increased with liberalization. Similarly, surveys of Japanese insect stores found a substantial number of beetles on sale that were not only prohibited for collection in their countries of origin but also prohibited in Japan under the Plant Protection Act and, in some cases, listed under CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.17

The environmental impact of the expanding Japanese market on the countries of origin was one concern for conservationists. But they also found three issues closer to home to worry about.18 Adult stag and rhinoceros beetles are vegetarians, living on tree sap and plant juices. The larvae and imagoes are important in the early stages of forest decomposition, mechanically breaking up decayed wood and creating the conditions for microorganisms to do their work. Beyond this, though, not much is known about their ecology. The obvious possibility was that powerful newcomers that liked similar niches would outcompete local species for food and habitat, threatening both the Japanese beetles and their food source. Goka and his colleagues were also concerned that the foreign beetles would bring unknown parasitic mites, which could undermine local beetle populations—in the same way that the varroa mite, exported from Japan with commercial hives, has devastated the European honeybee. And they worried, too, about the reduction of genetic diversity through interbreeding. Back in the lab, they created a “Frankenstein stag beetle,” successfully mating a female Sumatran Dorcus titanus—a popular pet—with a male from one of Japan’s twelve endemic subspecies. The sex wasn’t pretty, with the Indonesian female using what the scientists called “violent cruelty” to force herself on the reluctant Japanese male. But the resulting larvae grew into large fertile hybrids, similar to other hyphenated Japanese beetles that the scientists later collected in the wild, making real the troubling specter of genetic introgression.19

In 2003, just as the beetle craze seemed to be cooling off, Sega launched MushiKing. Targeted at elementary school children, it was exciting, addictive, and elegantly simple, efficiently bringing together its audience’s passions for big beetles, obsessive collecting, competitive gaming, and souped-up graphics. Very soon it was Japan’s biggest-selling game franchise since Pokémon (and was doing quick business in Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines, too).

Sega rolled out a ruthlessly effective promotional campaign. They staged hundreds of thousands of tournaments and demonstration matches. They set up banks of console machines in department stores and hypermarkets. They flooded the country with ads. In 2005, they announced versions of MushiKing for Nintendo DS, Game Boy, and other handheld devices. That year Sega began a spin-off anime series on Tokyo TV. In 2006, they released the anticipated blockbuster movie.

There was no question that MushiKing added value to the commercialization of stag and rhinoceros beetles. Nor that in doing so it intensified the paradoxes. Its mention provoked resigned smiles from the curator and docent in the hallway of the Itami City Insectarium, just as it did in similar conversations elsewhere. This was the summer of 2005, the height of the phenomenon, and it was obvious that the game had crystallized many insect people’s ambivalence about the form the beetle boom was taking. Keen as they were to inspire the public, happy as they were to see the excitement with which children entered their museums and stores, they had little enthusiasm for the game’s elevation of beetle belligerence and worried about the narrowing of these animals’ identities to their most mechanical aspects, worried that children would think of them as tough toys, not living creatures.

But Sega anticipated the unease. As if to mock both fears and hopes, they wrapped MushiKing in a package that compounded the ironies. The game wasn’t just an intensification. It was an environmental parable, and its plot was the same classic story that the insect people themselves were trying to tell.

MushiKing described the destruction of Japan’s indigenous fauna by an invading army of fugitive imported beetles. And it enlisted Japanese children in the fight to save the nation’s endangered species. It was an apocalypse story in the tradition of the monster movies and TV shows that first made kuwagata and kabutomushi popular in the mid-1960s. It lifted its instantly recognizable plotlines from pop media, and it revealed that the scientists were drawing on those sources too. Sega and the entomologists were telling the same story. They were telling it to the same audience. And as was obvious, Sega was telling it much more seductively.

5.

Before MushiKing, before the Plant Protection Act, before Mushi-sha, before inflatable kabutomushi in summer festivals, before insect figurines in Akihabara, before the “Befriend a Cockroach” table at the Itami City Insectarium, before Kuwachan quit his salaried job to sell kuwagata full-time, before Sugiura Tetsuya came home from Brazil with butterflies, before Miyazaki turned the Lady Who Loved Worms into Princess Nausicaä, before Tezuka turned Jiminy Cricket into Astro Boy, before Yoro Takeshi and his school friends hiked the mountains of Kamakura, before all of that—though after so much else—Yajima Minoru, still a konchu-shonen, a fourteen-year-old boy stumbling through a dark nightmare of personal and collective trauma, stood on the lip of a water-filled crater among the smoldering remains of wood-frame Tokyo—a city all but obliterated in the firestorm ordered up by Robert McNamara—and there, on the rim of the bomb crater, as all around him people scrabbled in the ruins for the remnants of their lives, he watched a dragonfly settle on a floating shard of wood and, as if nothing were any different, lay her eggs in the stagnant water. “That dragonfly didn’t care about all the corpses,” he wrote fifty years later, the image still vivid in his mind. “In the midst of that terrible reality, in spite of everything that was going on around her, she was alive and strong.”20

Yajima-san survived the war, but only just. He writes of what he witnessed as if from a dream, a trauma-dream with all its strange infoldings of linear time. The thousands of burned and rotting corpses. The young woman alone in a charred field cradling two bundles: under one arm her colorful kimonos, under the other the blackened body of her child. Tokyo is a “sea of fire.” Outside the factory in which he was working, he watches shrapnel explode as if in slow motion. He sees people dig useless shallow trenches in the ground for shelter, uncomprehending of the power of the B-29s. After the night of the Great Tokyo Air Raid, in which more die than even at Hiroshima, he watches the survivors gather up the piles of burned bodies. At a train station, caught in a stampeding crowd strafed by an American aircraft, a man, shot dead, falls on top of him.

Yajima-san was a sickly child. In the years leading up to the war, he came down with jaundice and spent a long time at home unable to attend school. Every day on the radio, he heard news of the successes of the Japanese military. Around him, the excitement mounted. In middle school, the students were told they were no longer children. Military exercises were compulsory. His classmates craved the honor of sacrificing themselves for the nation. His sickness, they said, was evidence of a weak mind. When he again fell ill, he was not permitted to be absent from school. As militarism increased, his health deteriorated further.

After the war, he contracted lung disease. His uncle, shell-shocked in the air raids, had moved to Saitama, in those days outside Tokyo and a place of rural calm. Here, exploring the countryside, Yajima Minoru recovered his connection to the natural world, to the dragonflies, tadpoles, ant lions, and cicadas he’d played with while in elementary school. In the fall, he helped supplement the household’s diet of poor-quality American relief bread and corned beef with locusts from the rice fields. If you observe locusts closely, he says now, you see that their eyes are really kawaii, and—just as cute—you see that when people approach, the animals move around to the opposite side of the rice stalk. In those days, though, it was all hunger all the time, and he thought of the insects only as food, doing his best to trap as many of them as possible.

In 1946, his doctor ordered a year of rest. Yajima moved back to Tokyo and discovered Osugi’s translation of Fabre’s Souvenirs entomologiques. He was fascinated by the way Fabre looked so closely at his animals and by how he reasoned from analogy. He was deeply impressed that the Insect Poet asked his questions of the living creatures he saw around him at l’Harmas; he was moved by Fabre’s curiosity and the vigor of his writing, and by the way he took you into the insects’ world, a world Yajima so badly needed at that moment.

Inspired, he spent five months studying the natural history of the swallowtail butterflies near his home. Just a short time before, a train full of students had been massacred on this spot by a U.S. plane. Often, he just sat and stared at the animals fluttering over the scene, immobilized by their life force and beauty, just as he was by the dragonfly in the bomb crater during the war. Looking back now, he sees his immersion in the swallowtails as the therapeutic compulsion that released him from the weight of the war and its afterlife.

Perhaps, as it does me, this story makes you think of Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, Li Shijun, Joris Hoefnagel, Karl von Frisch, Martin Landauer, Jean-Henri Fabre himself, and of other people for whom an insect universe provided an often-unexpected refuge. Perhaps it brings to mind people who, to put it another way, entered the world of insects and were, in turn, entered by it, who at times were swallowed up by it and who at other times found their bearings inside it, such that the normal scale of existence—the standard hierarchies of being—in which we know small things because they are physically smaller than we are and we know lesser things because they lack our capacities, was no longer a basis for either action or meaning, and such that the enormity of the circumstances that bound their lives could assume another proportion and a different place in their world, such that the world itself could become immeasurably larger and unconfining.

At some point during the solitary months spent observing swallowtails, Yajima Minoru made the decision to dedicate his life to studying insects. It was almost sixty years later when CJ and I met him for lunch in a cafeteria in the Tocho, Tokyo’s monumental two-towered city hall. By then he was one of Japan’s most eminent biologists, the creator of the world’s first butterfly houses, a maker of popular nature films, a leading conservationist, the pioneering developer of numerous insect-breeding protocols, and a science educator committed especially to sharing his love of insects with children. He was full of energy, telling us eagerly about his newest project, Gunma Insect World, which includes a spectacular butterfly house (designed by the architect Tadao Ando) and a substantial area of community-restored satoyama. It was due to open the next day, and we were all disappointed that CJ and I wouldn’t have time to visit. Yajima-san was kind, unassuming, generous with his time, and infectiously positive. We talked for a long while and afterward posed for photographs, tiny as ants in front of the colossal municipal building.

6.

The destruction of Tokyo was also the destruction of a thriving commercial insect culture centered in the city. “We were back to the beginning,” wrote the historian Konishi Masayasu, referring to the mushi-uri, itinerant sellers of singing insects who had first appeared in Osaka and Edo (Tokyo) in the late seventeenth century and who reappeared after the war to hawk their cages in the ruins of the capital.21

It’s not difficult to imagine the special importance at that moment of these animals, with their bittersweet songs of melancholy and transience, their cultural intimacy, and their unconditional companionship. But the mushi-uri were not walking the streets by choice. The bombings had destroyed Tokyo’s insect stores, and although the traders soon managed to set up roadside stalls in the Ginza shopping district, even then they were still back at the beginning: their breeding infrastructure had collapsed, and like the original mushi-uri, the postwar traders were simply selling animals they trapped in the fields.

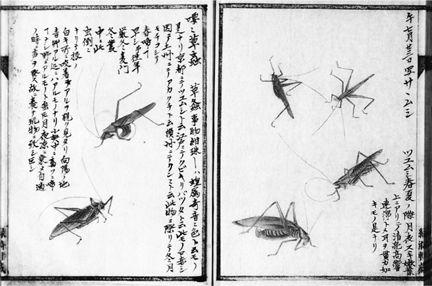

Japanese insect traders had known how to breed suzumushi (bell crickets) and other popular insects by the late eighteenth century. They had also discovered that by raising larvae in earthenware pots, they could accelerate the insects’ development cycle and increase the supply of salable singers, inventing techniques that are still in use today (among cricket breeders in Shanghai, for instance). Konishi describes a florescence of insect culture under the Tokugawa shogunate, that long period of relative isolation, from 1603 to 1867, when the possibility of external travel for Japanese people was strictly limited and the only point of entry for foreigners was through the port of Nagasaki. He notes the existence of clubs for the study of animals and plants in Nagoya, Toyama, and elsewhere; he describes the biennial residence in Edo of the daimyo, the feudal lords, during which the notables and their intellectual allies spent their leisure time collecting, identifying, and classifying insects; and he discusses the long-standing scholarly interest in and gradual incorporation of honzo, Chinese materia medica, a healing corpus that includes not just plants and minerals but insects and other animals.22 Rather than making specimens in the manner of the European naturalists, these insect lovers, the mushi-fu, preserved their collections in paintings annotated with observations, dates, and locations. Prominent artists such as Maruyama Okyo (1733-95), Morishima Churyo (1754-1810), and Kurimoto Tanshu (1756-1834), whose Senchufu is one of the incomparable treasures of the period, painted from life to produce portraits of insects and other creatures that not only were outstanding in their delicacy and precision but also were organized serially in a way that prefigured the arrangement of the zukan guides used by insect collectors today.

Konishi calls the Tokugawa shogunate the “larval stage” of Japanese insect studies. Despite their commitment and ingenuity, without sustained interaction with Western naturalists the mushi-fu were merely incubating their passion, he says, awaiting the external stimulus that would trigger its transformation. To Konishi, it was only through the energy unleashed in the Meiji period (1868-1912), with its eager embrace and importation of Western knowledge, that Japanese insect love entered the modern world and found its adult form. That moment of modernity can be dated to 1897 and the response of the Meiji government to the invasion of the national rice harvest by unka leafhoppers. In Japan, as in Europe and North America, entomology—the study of insects according to Western scientific principles—was tied from the beginning to pest control and the management of human and agricultural health.

This journey from enthusiasm to entomology is a standard narrative of Japanese science and technology, late on the scene but quick to play catch-up. As an account of a passage from darkness to light it closely parallels the conventional narrative of the scientific revolution in Enlightenment Europe two centuries earlier. But as many scholars have pointed out, these histories not only rather take for granted the Enlightenment/ Meiji belief in the superiority of science over other forms of knowledge but also assume too easily the distinction between them, underestimating the continuities that tie earlier ways of understanding nature to those that come to count as modern, and overlooking the fact that enthusiasms and instrumentalities persist together side by side and often without contradiction or conflict, in the same pet store, in the same magazine, in the same laboratory, even in the same person.23

On the other hand, there’s little doubt about the surge of energy in Meiji Japan that resulted in insect love being recast in entomological terms and supported by an array of institutional innovations. Konishi describes the “fever” for beetles and butterflies that took hold among biology students at the newly formed Tokyo University (1877); the groundbreaking publication of Saichu shinam (1883), a handbook of advice on collecting, preserving specimens, and breeding (drawn largely from Western sources) by Tanaka Yoshio, the founder of Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo; and the opening of three stores in Yokohama selling Okinawan and Taiwanese butterflies to sailors and other foreign visitors.

Half a century later, the descendants of the first patrons of those butterfly stores would bomb the emergent industry back to its eighteenth-century beginnings. Somehow, Japanese insect culture recovered with the same alacrity that had allowed it to seize upon Western science in the years following the Meiji Restoration. Somehow, the survivors of the destruction of 1945 drew strength from trauma. Yajima-san meditates on the life force of the dragonfly laying her eggs in the flooded bomb crater. Shiga Usuke, the founder of the country’s most eminent insect store, describes how he buried his precious supply of specimen pins in one of those shallow Tokyo bomb shelters and how, returning after the war to find them rusted and useless, set about designing more durable equipment, succeeding many years later in manufacturing instruments from stainless steel.

7.

Shiga Usuke was born in 1903 into a family of landless peasants in the mountains of Niigata Prefecture, northwest of Tokyo.24 Like Yajima Minoru, he was a sickly child who spent much of his time confined to his home—in Shiga’s case because of malnutrition. When he was five, he went blind after a simple cold turned into a fever. Each week, his father carried him three and a half miles to the nearest doctor. Eventually, Shiga-san regained the vision in his right eye but not in his left.

Despite his poor health and having to work to help his family, Shiga-san was an outstanding student and, as a result, was sent to Tokyo for high school. Unlike the insect men whom CJ and I encountered, he was never a konchu-shonen. In fact, he writes, he had little awareness of his environment and no memory of ever hunting insects as a child. He explains this as an effect of poverty and sickness and his preoccupation with work, but quickly interjects a doubt: are these simply excuses for the insensitivity he once had to nature, an insensitivity, he adds, that was normal among those around him?

High school was uneventful. He worked in his headmaster’s household and graduated at fifteen. It was then that he found a position at the Hirayama Insect Specimen Store in Tokyo, one of only a very few businesses in the city that made specimens for collectors.

Hirayama employed two workers. One was assigned to the store and one to the household. Shiga-san was the household servant, tasked with cooking, shopping, and cleaning. Despite this, he soon began to take notice of the store’s collection. Surrounded by insects, he started to see things he’d never seen before. He looked closely and observed differences, details of color, shape, and texture. He found himself looking more carefully, finding the specimens more interesting, excited by their unexpected beauty. Very quickly he determined to make a life as an insect professional. Soon he was bribing the store apprentice with candies to show him how to collect—at that time, houses in the city were surrounded by green space, and it was easy to find insects—and how to prepare specimens. But even as he became fascinated by all the variety, it also overwhelmed him. How could he ever hope to master this field? Hirayama carried no books or good-quality zukan in which to explore, and the store owner had no interest in furthering Shiga’s ambitions. Thrown back on his own resources, he stole time to study the shop’s collection, memorizing the names of species and matching them with the number and patterns of wing spots and the size and shapes of the markings.

Among Hirayama’s insects, he was in a dreamworld. Seen through a hand lens, every specimen was astounding, especially the butterflies. But back in the world of men, things were different. People were constantly reproaching him: why did he waste his time on this dross? Their contempt was intimidating and oppressive. Even his father—an open-minded man who supported his impoverished family by fixing umbrellas, making balloons, giving massages and acupuncture, and telling fortunes, and who was gaining a reputation as a midwife (an occupation forbidden to men)—was hostile to his work. People judged insects only according to whether they were useful or dangerous. It was acceptable to eliminate them but not to collect them. Away from Hirayama, Shiga-san remembers, he felt that he, too, was just a mushi.

In those days, insect collecting was confined to a small section of the social elite. Hirayama’s customers were drawn largely from the kazoku, the Meiji hereditary peerage. Rather than following the Tokugawa daimyo in catching the animals themselves, these men ordered their insects from the specialist stores. They coveted specimens as cultural capital in what they considered the manner of the European aristocracy, displaying them alongside other high-value objects in the guest rooms of their houses. At the same time, the formation of boys’ insect-study associations across the country was a sign that the government’s support of scientific entomology was stimulating a wider interest. However, with boxes imported from Germany and nets made of silk, the essential tools for collecting remained prohibitively expensive.

In 1931, Shiga Usuke left Hirayama to start his own store. He was motivated both by the need to escape his exploitative situation and by a determination to make the world of insects available to everyone, not just the wealthy. And like Yajima Minoru, he wanted especially to reach out to children. He states his belief clearly: if people care for insects when they’re young, they grow up with an ethic of care that extends not only to nature and the smallest creatures but also to all beings—human and otherwise—that surround them. He named his new business Shiga Konchu Fukyu-sha, Shiga’s Insect Popularization Store, signaling both his modernity and his pedagogical intentions with the scientific term konchu rather than the idiomatic mushi.

Shiga-san threw all his creative energies into his new enterprise. To draw passersby, he placed tables on the sidewalk outside the store and staged demonstrations of specimen mounting. Not satisfied with the size of his audience, he struck a deal with Tokyo’s four leading department stores—sophisticated, contemporary venues that captured the spirit of the new science he was promoting. He and his friend Isobe would spend a week in the stationery section of each store answering questions at special insect-inquiry booths and demonstrating Shiga’s proprietary collecting tools: the low-cost collapsible pocket-insect-collecting net and new copper, nickel, and zinc pins, all of his own design. The demonstration sessions quickly became popular. Children flocked to the events, eager to ask questions. Seeing them staring so intently at his hands as he worked, Shiga-san recognized himself in his first days at Hirayama’s store and felt happy.

This was 1933. That year a new magazine, Konchukai (Insect World), started to publish field reports from middle school students around the country. About the same time, Shiga Usuke began to receive orders for mounted specimens from schools (orders he refused, deciding that students would learn more by preparing their own specimens than by viewing ready-mades). Those years saw the establishment of insect stores, magazines, entomology clubs and associations, networks of professional and amateur collectors, and university departments of entomology—and not only in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto but also in small towns and in many parts of the country. The rising popularity of insect study was clear, as was the maturing of its culture and infrastructure. Indeed, these were the years in which that density of people and institutions came into being which enabled insect commerce to recover so rapidly from the ravages of military defeat.

But for Shiga Usuke, this prewar growth of insect culture did little to displace the elite character of insect collecting. There may have been more children handling more specimens than ever before, but so far as he could see, they all still came from exclusive schools and wealthy families. Rather than the story of the essential national affinity for insects CJ and I heard from Okumoto Daizaburo and others, Shiga Usuke describes class-based practices of insect love and insect hostility that are selective in their objects (crickets, jewel beetles, kuwagata, dragonflies, fireflies, houseflies) and vary across time. Some of those practices, such as chasing dragonflies and listening to crickets and cicadas, have appealed both to the connoisseur and to a wider public. Some, such as the use of insects for food, have long been restricted, as Sugiura Tetsuya pointed out, to poorer people in now-gone times and places. Some, such as the use of insects in healing (cockroaches for chilblains, frostbite, and meningitis, for instance), became less widespread as kampo medicine, based on Chinese materia medica, was first banned in the Meiji era and then rehabilitated in the limited form of complementary, primarily herbal therapies alongside allopathic medicine. Collecting, the scholarly activity to which Shiga, Yoro, Sugiura, and Okumoto are committed (the activity that places them in the august aristocratic tradition of the daimyo and the more ambivalent aristocratic tradition of the European colonial naturalists, as well as in the satisfyingly iconoclastic lineage of Jean-Henri Fabre), begins to generalize from its origins only with Japan’s postwar economic expansion, the rise of pop-culture media, and the creation of a new middle class equipped with surplus income and the leisure time in which to enjoy it. Other practices, most obviously the breeding and raising of kuwagata and kabutomushi, arrive as something new and unsettling, attracting a new type of konchu-shonen with new experiences, new insect equipment—manga, anime, inflatable beetles!—and newly complicated ideas of what an insect might mean in their and their families’ lives.

As well as expendable income, the unprecedented economic growth of the postwar era brought the unforeseen shock of environmental disaster, most famously with the mercury poisoning at Minamata, in Kumamoto Prefecture, in 1956 and again in Niigata in 1965. A growing sense of national dystopia contributed to the emergence of new forms of nature appreciation and protection. The first mushi boom, a combination of new consumerism and new environmentalism, arrived in the mid-1960s. Inspired, as we have seen, by the stars of the kaiju (strange-beast) movies—especially the very popular Mothra, a butterfly-moth monster who uses her powers for good—and “special effects” TV series like Ultraman, as well as by the insect creations of Tezuka Osamu and other manga pioneers, it fixed on butterflies, kuwagata, and kabutomushi as its objects of desire. For the first time, the big beetles, considered ugly for centuries, were in greater demand than the suzumushi and their singing comrades.

These years saw the publication of affordable insect encyclopedias, high-quality field guides, new collectors’ magazines, and in 1966, the opening of the butterfly-shaped insectarium at Tokyo’s Tama Zoo (one of Yajima Minoru’s first major projects). Perhaps most tellingly, these were the years when the summer collecting assignment became a fixture of the elementary and middle school curricula.

These were also the years when Shiga Usuke—who would soon receive an award from Emperor Hirohito for his collecting tools, an award, he said, that for the first time made him feel accepted in his profession—petitioned the Ministry of Education to stop department stores from selling live butterflies and beetles. They were, he said, encouraging students to cheat on their summer projects: teachers were unable the tell the difference between store-bought and wild animals. Actually, Shiga-san added, teachers were giving higher marks for the purchased ones because they were in better condition. How could students learn anything from insects if they were just one more commodity? The ministry agreed, and the stores went back to selling specimens and Shiga-san’s innovative and beautiful collecting instruments. It was only in the 1990s, with the rise of the insect pet shops, the liberalization of imports, the heightened commercialization of the mushi trade, and Shiga’s rearguard action long forgotten, that the stores once more began stocking their shelves with beetles.

8.

Soon after Sega released MushiKing, the Ministry of the Environment began hearings on a major new piece of conservation legislation. The Invasive Alien Species Act was designed to remedy the gaps in the Plant Protection Act that had allowed the black bass, the European bumblebee, and other unwelcome immigrants to slip across the nation’s borders. Like most such debates, this one was immediately caught in the rhetoric of exclusion and belonging that the language of native and invasive incites—the same rhetorics that led Kouichi Goka and his colleagues to identify so closely with the reticent male Dorcus that they forced into sex with its cruel Indonesian cellmate. Given that Japanese nature is often taken as a defining element of national and personal identity, it is easy to see why the debate over this legislation was so fraught.

One of the more controversial questions was whether kuwagata and kabutomushi would be listed on the act’s roster of prohibited species. Conservationists lobbied for inclusion, concerned about both the continuing effects of beetle imports and the logic of collecting more generally. They had long argued that collecting was harming native species through damage to habitats from tree felling and other indiscriminate methods, through the removal of breeding populations from the wild, and through the impact of released foreign animals.

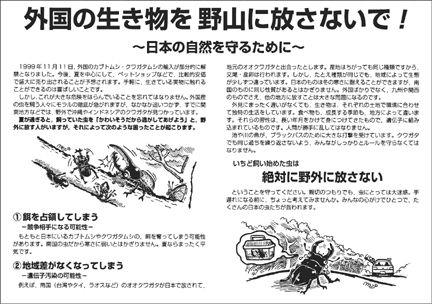

Representatives of insect commerce were well organized. After all, they were the ones with the most to lose. Tokai Media, the publisher of Be-kuwa!, sponsored a nonprofit organization, the Satoyama Society, which worked to enlist the industry in a preemptive campaign of conservation education that included articles in the specialist magazines, lectures, posters, flyers promoting more careful management of beetles, and the formation of local collecting clubs. The Satoyama Society promised their beetle-industry colleagues that the education campaign would generate lecture fees and new customers.

People from Mushi-sha gave expert testimony at the hearings. They estimated a core of 10,000 to 20,000 amateur breeders, another 100,000 beetle-keeping adults (mostly middle-aged men), and millions of children raising insects from eggs. They argued that with estimates of up to 5 billion non-native beetles in circulation inside Japan, it made no sense to talk about import controls. The real danger was not from animals entering the country but from those already here. Controls would only undermine the educational and moral value of collecting. Instead, like their allies in the Satoyama Society, they proposed to manage the situation with a campaign to educate their customers about the consequences of abandoning their animals.

By the third public hearing, it was clear that the industry and its allies had won the day. Few beetle species were included in the final document, and those that were appeared under the nonrestrictive “organisms requiring a certificate” column.25 However, conservationists were involved in a larger struggle that didn’t solely target the commercial collectors. Many also disliked what they saw as the unnecessary destruction behind the vast private collections of scholars like Yoro Takeshi. They worried about the moral effects that the sanctioned killing of animals had on children. For a number of years, and with success in Tokyo and elsewhere, they had worked to stop schools from assigning the summer entomology projects.

My first thought on hearing this was for Kuwachan and his dream of fathers, sons, kuwagata, and kazoku service. But collectors such as Yoro Takeshi and Okumoto Daizaburo were forced on the defensive too. Aren’t we, they argued, like Fabre, both scientists and insect lovers? Don’t we, too, have reservations about the beetle boom? Aren’t we, perhaps even more than the conservationists, committed to fostering a world of sensitive and creative nature loving, especially among children?

It was true that the commercialization of kuwagata had been highly damaging, they agreed, although the decline in numbers was due as much to loss of habitat through real estate development as to overharvesting. But in general, collecting had no effect on other insects: their populations were simply too large and reproduced too rapidly to be affected. The more serious question was about killing. For Yoro-san and his friends, a truly deep relationship with other beings results from interspecies interaction, not separation; it results not from abandoning communication in the name of paternalist stewardship but from the radical change in consciousness that comes with developing those hard-to-acquire “mushi eyes.” To find insects, you have to understand them, you have to find a way into their mode of existence. The focused attention that is needed to enter their lives is a form of training, philosophical as well as entomological. It brings a knowledge of nature that is inseparable from an affection for nature and an expansion of the human world. Killing insects is painful, but it is also meaningful. Echoing Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, Yoro-san told us that he had enough insects now. He had stopped killing them. Okumoto-san told us he never killed them but collected live specimens and pinned them only after they had died a natural death.

Shiga Usuke also experienced this unease. One year, on the anniversary of the opening of his store, he invited a Buddhist priest to come to Tokyo from the mountains and perform kuyou to console the souls of the departed. Instead of photos of the dead, he arranged specimens. Instead of favorite human foods, he arranged insect food. This was more than seventy years ago, in the 1930s. The sense of guilt about other beings, he writes, the sensibility that killing living things is wrong, is far from new. He tries not to care about this, but he can’t escape it. He often wonders which is better: to live as a mayfly for only one day or to survive as a specimen for hundreds of years.

I’m happy that I’ve known insects, says Yajima Minoru. Shiga Usuke feels the same way and adds that it’s easy to get to know them. All you need is a magnifying glass and a net (maybe one of his inexpensive folding pocket nets).

As you observe tiny insects, writes Shiga-san, you’ll grow more interested in nature and you’ll find more pleasure and more satisfaction in the world around you. There is really nothing better than getting to know insects. The relationship between human beings and nature starts with insects and ends with insects, he says. And then he adds: my life has been exactly like that.