The Illustrated Insectopedia - Hugh Raffles (2010)

Sex

1.

In September 1997, Keith Toogood, described in the British press as a forty-four-year-old factory worker and father of two, was arrested at his home by customs officers who had seized a suspect item at a London mail-sorting office. The package originated in New York with a mail-order company called Expressions Videos and contained ten films, including Clogs and Frogs, Barefoot Crush, and Toad Trampler. Appearing eleven months later at Telford Magistrates’ Court, Mr. Toogood pleaded guilty to importing obscene material and was ordered to pay a fine of £2,000 plus costs. A customs spokesman, Bill O’Leary, commented that officers with twenty-five years’ experience “thought they had seen everything before they came across this.” The videos, he said, “are too grisly to describe.” Mike Hartley of the West Midlands Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals agreed. These so-called crush videos, he told a reporter for The Scotsman, “are as sick and depraved as you can get.”1

2.

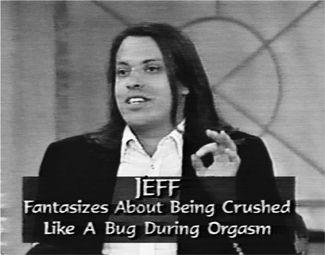

Four years earlier, with Toogood’s arrest and all that would follow still unimagined, Jeff Vilencia was living and making movies in his mother’s garage in Lakewood, a suburb south of Los Angeles. He was enjoying the unexpected art house success of two short films: Squish, which features a woman squishing grapes, and Smush, which involves a different woman smushing a large number of earthworms. Both movies had screened at film festivals, some of them prestigious, and with his surfer looks and easy smile Jeff was proving an engaging interviewee, charming, articulate, and disarmingly direct. “A crush freak,” he patiently explained to the rather uncertain host of a Fox daytime talk show, “is one who desires himself tiny, insect size, bug-like, and then stepped on and squashed by the feet of a woman.”

“I’ve always been a pervert!” he merrily replied to an audience member’s question about how long he’d felt like this. If he was going to be a freak, he’d be his own freak. He was poised and relaxed, enjoying confounding expectations. This wasn’t some guy who had trouble getting girls—unlike the timid-looking Pie Man with whom he shared the stage. (“Sexuality has power in it,” Jeff pointed out, his tone somewhere between sex ed and a laundry-liquid commercial, “and we’re bound by humiliation—especially the Pie Man and myself.”)2

Jeff passed on the opportunity to treat the studio and TV audience to a full description of what he meant by humiliation. He explained, instead, that since he’d made his first movie, in 1990, he’d become the linchpin in an international brotherhood of 300 crush freaks (“all gentlemen, by the way, very intellectual people”). Interested individuals could contact him at Squish Productions, a mail-order business he ran out of his home in Lakewood, from which they could purchase his videos or a copy of The American Journal of the Crush-Freaks, the first of two books that he wrote and published as a way to build the crush community.

The Journal bursts with compressed energy, its pages packed with information and opinion: extended discussions of the fetish (its histories, its pleasures, its variations); a lengthy interview with Jeff in the foot-fetish magazine In Step (Jeff on his movies: “We have life, and the origin of life is sex, or the sexual act, and we have death which is the very final, very frustrating, very dark unknown thing. Somehow, occasionally these two things collide in some type of an orgasmic imagery”); a demographic analysis based on letters Jeff received after the interview was published (“A large concentration of the Crush-Freaks hail from the north and east coast, with a large amount of foot fetish people coming from New York”); reproductions of those letters (“I’ve read your interview in In Step and was very happy to learn that I am not the only one that has the fantasy of being stepped on by a Giant Woman!”); a helpful list of phrases guaranteed to excite a crush freak (“I’m going to squish you through my toes”); a review section highlighting gardening and entomology books that contain scenes of insect killing and are ranked from one (“Eeeeh”) to five pumps (“Thru the roof! Obviously the author herself has the crush fetish and this is her way of expressing it”); an extended interview with Ms. J, crush mistress, about her craft (“I do not step on the little spindly legged spiders ’cause they’re my friends. But when it comes to bugs, I mean they’re just icky little creatures so I can’t think of why they shouldn’t be stepped on!”); casting notices and responses (“I’m a model and commercial actress with a theatrical background. I have exactly what you want, BIG FEET. Enclosed is my modeling comp—read sizes carefully”); and much more. Interspersed among all this—some of it playful, some of it funny, some of it a bit scary, some of it a bit sad, all of it in his take-me-as-I-am, straight-from-me-to-you writing style—are Jeff’s crush fantasies, his stories and reminiscences that deploy what he identifies as the three key narrative elements of the crush fetish: power, sex-violence, and voyeurism.

Rei, Jeff’s girlfriend, has placed him in a small jar. She’s poked four or five airholes in the lid. She is on her way out for the evening with a couple she met through an ad in a foot-fetish magazine. As she leaves, she switches out the light. Jeff dozes off in the jar.

Rei comes home. The couple tie her up and lick the soles of her feet. (“She knows that I am helpless and can do nothing but watch.… I like to watch! I like to be bug-sized and trapped and forced to watch.”) Next thing he knows, Rei is shaking the jar like a bottle of hot sauce. His head smashes against the glass; he thinks his arm could be broken, his skull might even be fractured. She unscrews the lid and pours him out onto the carpet, flicks him over with her big toe. “Hey, you guys, look what I found, a squirmy little bug!”

The three of them tower over him. He tries to move but feels glued to the floor. “I must look like a tiny, squirmy silverfish or an oversized white worm or maggot.” He squirms helplessly. Rei peers down: “Look, there on the floor, you guys, it’s my boyfriend. I know it looks like a strange insect but it’s him.” One of her new playmates makes to fetch some tissue. “Why bother,” says Rei. “Let’s just step on him!”

It all happens in super-slow motion, the way we might guess that time occupies another scale for tiny short-lived beings, the way time drifts to a near halt in moments of extremity. “She raises up her huge foot. I try to lift my head but it is no use. I can’t move. I hear her speak one last time. ‘Squish that bug!’”3

And now it all converges. As he lies there immobilized, willing the foot toward him, begging it toward him, the foot descending toward him, the giant foot right over him, he spontaneously ejaculates and, right then, exactly then, the sticky foot crushes down on him.

My guts gushed out of me as my eyeballs popped out of their sockets. My inner matter came squishing through every orifice of my body! … My sides split open, and all of my intestines smushed out like a half-flattened grape. I became a tiny bloody mess under the ball of the foot. The warm foot twisted back and forth to make sure I was smashed. Half of my tiny body was broken up into bits and ground into [the] carpet. The other half of me was stuck to the bottom of the foot like to the skin of a squished grape.4

Perhaps these words speak to you only if you’re already inside this story and captive to its call. Perhaps different writing could better measure this orgasmic collision of death, sex, and submission. Or perhaps the question is meaningless because these stories are functional, not educational. But Squish and Smush—Jeff’s art films—somehow manage to create experience for all kinds of viewers, not only the already committed. Maybe that says something about the difference between print and film, the modes of attention they create. Or maybe just about the inescapability of these particular movies, compressed and compact, distilled down to just pure idea, inexorable and unambiguous.

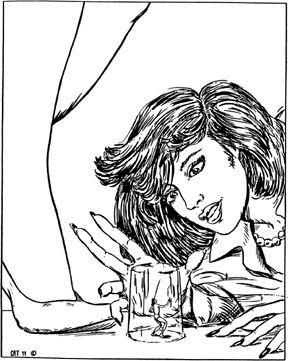

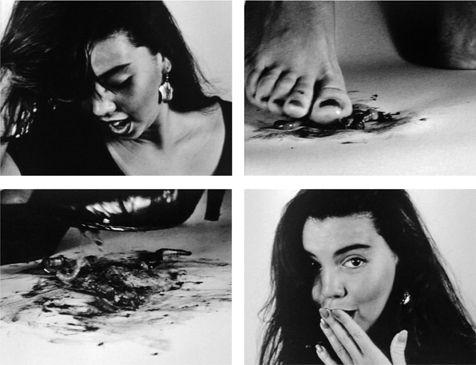

These are short films, five and eight minutes only, shot in high-contrast black-and-white. Erika Elizondo, the star of Smush, appears in a dark dress on a bright white background. She’s right there in extreme close-up over and over, her cute baby-fat face, her mobile expression, a little innocent, a little knowing, a little flirty, a little unpredictable, a little inaccessible, her pedicured feet, the fleshy soles soon soiled with bloody mess of worm.

“I weigh one hundred twenty-two pounds and have a size eight-and-a-half shoe,” she begins, striking a few exaggerated runway poses. “I love to smush worms. I love to tease them by pressing down softly at first.” She talks like Betty Boop, her voice high-pitched with lots of echo. She’s talking to you, she knows what you like, and she’s going to give it to you. She’s not judging you, she’s playing with you, and she’s toying with you too. She’s giggling, but she’s in charge. She wrinkles her nose in mock disgust. “It’s fun to pretend that the worms are little men under my feet. Even better I like to pretend that they are old boyfriends and this is my revenge.” The amplified squelch of worms underfoot sounds like squealing. Eight minutes feels very long as she teases the animals, laughs, poses, switches into black pumps. (“These pumps belong to my mother. I decided to use them because she didn’t want me to be in a foot-fetish film!”) She stamps her bare feet on the flailing animals, and their intestinal fluids shoot from their anus like an orgasm, like the orgasm Jeff has the instant before Rei’s foot crushes him into messy oblivion. “You’re just a grease spot,” Erika Elizondo tells the worms as she grinds them into the bright white butcher paper.

Crush freaks loved the movies, which quickly became genre classics. You still come across people on fetish discussion boards trying to locate copies. But critics and festival audiences were unsure how to react. “It fascinates, but … pushes the limits of tolerance,” said a spokesperson for the Helsinki International Film Festival. It’s a “humane society horror show,” wrote Charles Trueheart in The Washington Post.

For Jeff Vilencia, the movies, the books, and the TV appearances were a celebration, an assertion of the right to live fully. “I love myself and my fetish and I won’t trade places with another fetish, ever! I love girls’ feet (sizes 8, 9, 10 and up!). I love to lick the soles and suck on their toes. I love to fantasize about being a bug and having her step on me and squish me! I masturbate about this two times a day,” he declared in the Journal. “We must be free to talk about sexuality and feelings,” he continued; “then all taboos will vanish.… We must move forward with teaching sexuality, and teach every child that sex and fantasy and fetishes are good things that can create a happy, healthy sex life which in turn will nourish a better relationship between partners. The world will be a better place through an understanding of sexuality and the meaning of this life experience. Many happy fantasies to you all whatever your kink may be. We are the Crush-Freaks—Step On Us!”5

3.

Keith Toogood’s arrest was just the beginning, Jeff told me as we sat talking in the afternoon sunshine outside a Starbucks in suburban Los Angeles.6 The British animal activists alerted the Humane Society in Washington, D.C. That organization, in turn, directed the district attorney’s office in Ventura County to Steponit, a video production company operating in its jurisdiction. On viewing the tapes, the L.A. cops reacted with the same disgust as the U.K. customs officers, but they were unable to build a case: the participants in the films were unidentifiable, visible only from the legs down; Steponit had already gone out of business; and it was unclear whether the videos had been produced within the three-year statute of limitations stipulated by the California animal-cruelty laws, the legislation that the D.A.’s office decided offered the best chance of a conviction.

Frustrated, law enforcement took the operation undercover. Calling herself Minnie, Susan Creede, an investigator with the Ventura County D.A.’s office, signed on to the Crushcentral discussion board and, in January 1999, made contact with Gary Thomason, a local producer and distributor of crush videos. Soon they were chatting online, and Minnie told Thomason how much she enjoyed stomping on mice with her size-ten feet in her boyfriend’s garage and, more important, how she had ambitions to star in a video. Thomason, whose productions till this point had been restricted to smaller animals—worms, snails, crickets, grasshoppers, mussels, and sardines—was taken aback by Minnie’s uncommon enthusiasm but was nonetheless intrigued. They met in person in early February, and with Minnie’s encouragement, Thomason felt emboldened to try something new. As he explained to California Lawyer magazine’s Martin Lasden, “Mice are very popular to at least 30 percent of the crush community, which makes them well worth the effort.”

Lasden reported that communication cooled off for a while. Then, in late May, Thomason wrote to tell Minnie about a new movie he’d completed, in which an actress had crushed two rats, four adult mice, and six baby mice, known as pinkies. He sent Minnie a clip, to which she responded, “Nice work.”

Three weeks later, Minnie, along with her friend Lupe—a Long Beach police officer named Maria Mendez-Lopez—arrived as scheduled at Thomason’s apartment. Thomason headed out to the pet store. Minnie asked him to pick up some guinea pigs, but when he returned thirty minutes later, the five boxes he was carrying each contained a large rat, sold to him as food for snakes. The guinea pigs, he explained, were too expensive.

From then on, it was all over pretty fast. Thomason closed the blinds and locked the front door. With some difficulty, he secured a reluctant rat by taping its tail to the top of a glass table—a valuable prop in that filmed from below, it affords a last-gasp point-of-view shot of the woman’s bloody soles. Lasden reconstructed what followed:

Thomason and his associate, Robert, raise their cameras.

MINNIE: I wish that was my ex-husband.

LUPE: Yeah, he was a real jerk.

A loud knock on the door.

THOMASON: Who’s there?

Police.

Panic. Thomason tries to free the rat. Before he succeeds, the door crashes in and eight plainclothes cops, guns drawn, rush the apartment.

Police! Police! Get on the ground.

“They were the most vicious cops you’ve ever seen,” Jeff told me. “They broke all his stuff. They stole his coin collection. They answered his phone when one of his relatives called: ‘Yeah, we know Gary. Did you know Gary was a fuckin’ pervert?’”

The police let Robert go but charged Thomason with three felony counts of cruelty to animals carrying a possible three years’ jail time. Bail was set at $30,000. Rifling through his confiscated computer, they found files identifying the actress in his previous rat movie. When they caught up with Diane Chaffin in La Puente, California, she still had the guilty shoes.

The section of the California Penal Code dealing with the inhumane treatment of animals was written in 1905, when the animals uppermost in legislators’ minds were farm stock. It defines an animal as any “dumb creature” and sanctions any person who “maliciously and intentionally maims, mutilates, tortures, or wounds a living animal, or maliciously or intentionally kills … [one].” The defense lawyers in People v. Thomason sought to limit the reach of this clause by citing the Health and Safety Code’s injunction that California residents have an obligation to exterminate rodents in their homes “by poisoning, trapping, and other appropriate means.”7 In the abstract, it seemed plausible to argue that mice and rats were excluded from protection (along with invertebrates, whose killing excited no legal controversy) and, moreover, that the approved methods of extermination also involved mutilation and torture. In practice, however, the prosecution had only to show the judge a few brief clips of Diane Chaffin in character for legal niceties to lose their traction. (“Hey, pinkie,” the court heard her tell the baby mouse, “I’m gonna teach you a lesson. I’m gonna teach you to love my heel.”)8

“You can kill animals all day long,” commented Tom Connors, the Ventura County deputy D.A. overseeing the case. “They do it in slaughterhouses. What matters is how you kill [them].”9 Nonetheless, Chaffin was charged in only three of the deaths. The D.A. was uncertain he could demonstrate cruelty in the cases of the other nine animals. What this meant in reality, Jeff Vilencia explained, was that the struggling of the adult rats was visible whereas the death throes of the tiny babies were not. “Isn’t that the most convoluted thing you ever heard in your life?” Jeff asked me.

4.

Squish and Smush are just two of Jeff Vilencia’s many crush-movie credits. The other films were released in his Squish Playhouse series of fifty-six titles, which he sold via mail order, mostly by word of mouth and through ads in porn magazines. None of these videos made it onto the film-festival circuit, nor were they intended to. “They were made for private masturbation,” Jeff told me, “for guys who had the fetish.”

The Squish Playhouse movies are in color and are much longer than the art films, lasting for at least forty-five minutes. They might involve crickets, snails, and pinkies as well as worms. They feature Jeff as an off-camera master of ceremonies and interviewer. And they employ plot conventions familiar to viewers of low-budget “amateur” porn, in which a premium is placed on the ordinariness of the women involved and the production of a fantasy of normality, the fantasy that these events could happen anywhere, anytime, that right now your doorbell might ring and a girl show up who’d love to do all this just for you, too.

It all happens in what looks like Jeff’s apartment. He starts out by interviewing the actress, his voice disembodied, deep and strong, like that of a friendly radio host. It’s low-budget but professional, though he laughs a lot, nervous laughter, and it’s clear he’s excited. He’s set this up and is running things, but there’s uncertainty in the air.

The actress sits in front of a white drop sheet. “How tall are you?” he asks her. “How old are you?” “How much do you weigh?” “What’s your shoe size?” He wants to hear fetish talk: “What drew you to the bug-squishing ad?” he asks. Elizabeth, the tall, dark-haired star of Squish Playhouse 42, dabs at her runny nose with a tissue and responds without hesitation. “Money!” she says, and they both laugh.

The woman might be shy. Jeff coaxes her into talking about how they met—in a parking lot!—asks what she knows about the fetish, how she feels about insects, about squishing insects, what her mom would think about her doing this, what she thinks of the guys who get off watching her do this. He elicits embarrassed giggles and a few insect-killing anecdotes. (“What kind of shoes were you wearing?”) He teases her. (“You are a monster!”) She goes to work.

It’s basic: a large square of white paper, a change of shoes, a few small animals. She might be wary, like Elizabeth, or she might be enthusiastic, like Michelle in Squish Playhouse 29. (“What did that feel like?” “It felt artistic.”) She pushes the animals around with her toe. He coaches. She pushes some more. The camera pulls in and focuses on the action. She crunches a few, grows in confidence, maybe gets angry with them, threatens them, mocks them, laughs at them, laughs at the situation, plays with them with her foot, pretends they’re her ex-boyfriend. (“You’re an asshole, you’re a prick, you fucked me over, you fucked my best friend, you humiliated me, you deserve to die, you need to die painfully, you need to have a very horrible, painful, excruciatingly, horrifically painful death,” Michelle says in a strangely uninflected voice.) She lets them escape a little, catches them again, kicks them around, applies more pressure, less pressure. Jeff pulls in for an extreme close-up on a cricket’s head sticking out from under her shoe. (“Look at him squirming, that’s cool, they suffer more that way,” Michelle observes.) They take a break to discuss the mess on the sole of her shoe. They start again: new paper, new animals, sometimes a whole new outfit.

There’s no slick editing, no effects, no pretense. It’s homemade, it’s right here, it’s happening in real time with real people. But what is happening? With the camera fixed on Michelle’s blushing face, Jeff prompts her to explain:

JEFF: The guys who are gonna watch this tape, you know what they’re gonna do, right? What are they gonna do?

MICHELLE: They’re gonna get off on it. (Embarrassed laugh.)

JEFF (also laughing): How are they gonna get off on it?

MICHELLE: They’re gonna jack off! (Both laugh.)

JEFF: So they’re gonna fantasize that you are crushing them. And they’re gonna get a hard-on and jerk off. What do you think of that?

MICHELLE: They’re gonna picture themselves as a bug. (Camera moves closer.)

JEFF: Yeah, and then what happens? …

MICHELLE (very quietly): I don’t know, I guess …

JEFF: Well, they picture themselves as a bug …

MICHELLE: Well, yeah …

JEFF: And then what happens? …

MICHELLE: And then I crush them, and it’s like I’m crushing them and not the bug …

JEFF: Wow! Can you believe this! Did you tell any of your friends about this fetish?

Michelle tells Jeff that she prepared for her role by watching his movies and dipping into the two volumes of The American Journal of the Crush-Freaks. Jeff tells me that these scenes were never rehearsed.

I know where Michelle got this idea that the men picture themselves as the bug. I’ve read the same books, watched the same movies, and I’d guess I’ve had some of the same conversations with Jeff Vilencia. It seems straightforward: “picture themselves” as a gentle shorthand for that intense identification at a moment of wildly disorienting arousal. But what exactly are Jeff and his fellow crush freaks identifying with?

At first, I pictured some kind of becoming, some kind of cross-species melding of two beings into something new, a bug-guy/guy-bug, something attainable by the triggering of ecstatic moments in the detailing of the fantasy. I imagined that this momentary bug-guy somehow felt himself to be occupying the psychic and physical lifeworld of the insect. And I liked that idea, because it opened the possibility of this being an unusual struggle to escape the limits of being human, rather than that more familiar human struggle for fulfillment and expression. It seemed utopian, in an unusual, messed-up kind of way.

But then I noticed that in Jeff’s fantasies—or at least in his fetish stories and movies—the woman always knows that the bug-guy is no bug. She knows that the bug-thing writhing on the carpet is Jeff. Sometimes—actually, quite often—she’ll have her big, strong boyfriend (often called Sasha) crush him for her, and Sasha might not know he’s crushing Jeff until she tells him afterward, or sometimes she might never tell him and Sasha might never know. But the woman always knows, and it’s the woman, the arbiter and architect of punishment, who matters in these stories.

Remember Jeff’s fantasy of being ground into the carpet by Rei and her friends, one story among many, a large number of stories, a small number of plots? Jeff is tiny, he’s squirmy, he’s disgusting, he’s worthless. He is good for nothing but crushing. He has the characteristics of an insect and deserves to be treated accordingly, with cruelty, without mercy. The players in this drama are quite clear on this point. Jeff is like a bug. But he’s not a bug. He’s not part bug. He’s not in-between bug. He’s definitely not trans-bug. He’s not even passing as a bug. He’s bug-like. Everyone knows that it’s Jeff down there on the carpet getting stomped: he knows it and Rei knows it and that couple licking her feet know it too. Remember what Rei said? “Look, there on the floor, you guys, it’s my boyfriend. I know it looks like a strange insect but it’s him.”

So even though Jeff likes to sign off as Jeff “The Bug” Vilencia, his aspiration is really quite modest: he just wants what a bug’s got—worthlessness, repulsiveness, vulnerability, squishiness. It’s not a huge transformation. He already has most of this. And he’s managed to find a positive value in it, discovered that, for him, humiliation is the fulfillment of desire. He can pay women to walk on him. But he needs more. He needs his bug-like nature to be made visible, and he needs to be forced to suffer the consequences—again and again and again.

And that’s why I’m guessing he’s not really a guy-bug/bug-guy, because, by necessity, none of this suffering and humiliation produces empathy or sympathy for the insect. How could it? Because suffering is pleasure and because the insect is just a container for all that dark pleasure, nothing more. The insect is the dark place that sucks up society’s disgust. It is the anonymous dark place that enables relentless repetition. Squish, squish, squish. Like a baby throwing its bottle to the ground again and again, every time it’s picked up, again and again, trying to figure out something that’s all at once obscure and vacant. Again and again. Nothing more.

Are you feeling it? That’s what counts here. Don’t worry about why they’re doing this, even though crush freaks themselves—cursed with the explanatory burden of a “minority sexuality”—have little choice but to fret about that all the time. Bastard child of foot fetishism, reject infant of giantessism, downcast cousin of trampling, alienated half sibling of zoophilia, evil twin of the messy thing.10 Everyone traces it to childhood, to an unanticipated glimpse of an unfortunate episode: mother, insect, foot. In that blink of a wide-open eye, something gets made forever, something gets lost forever.

To Freud, fetishism is a disavowal, “an oscillation between two logically incompatible beliefs.”11 The impossibility of resolution produces the constant return—to the foot, to the insect, to the explosive death, to the moment long ago before that bad thing happened. To the absent female phallus. Or maybe not. It doesn’t seem wholly serious when you write it down like that.

Still, it’s not just crush freaks who need to know. As we’ll soon see, everyone wants an origin story, everyone from Fox TV to the D.A.’s office to the Humane Society to the Judiciary Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. Why this need to unravel causation? To make sure it doesn’t happen again? To develop a cure? To nullify, justify, pathologize, normalize, criminalize? There’s agreement on all sides that this stomping is a symptom of something gone wrong. The only symptoms no one feels compelled to explain are the ones revealed in these inescapable demands for explanation.

Like most of us, Jeff is thoroughly inconsistent. Unlike most of us, he is highly quotable. “At this point in my life,” he wrote in the Journal, “I am more interested in the thing itself rather than its origin.”12 The bug gets squished. The man gets off. That’s what counts. Maybe you’re not feeling it. Jeff is feeling it.

5.

Georges Bataille begins his inspiringly unapologetic picture book, The Tears of Eros, in the voice of the utopian manifesto. “We are finally,” he announces, “beginning to see the absurdity of any connection between eroticism and morality.” Morality, he tells us later, “makes the value of an act depend on its consequences.”13

With the arrival of People v. Thomason in the summer of 1999, Jeff Vilencia, America’s only telegenic crush freak, found himself back in the media spotlight. But this time, everything was different. It wasn’t only hapless Gary Thomason who was making headlines. Crush freaks were also keeping cops busy in Islip Terrace, a suburb of Long Island. Acting on a tip from Thomas Capriola’s ex-girlfriend, the police raided the twenty-seven-year-old’s bedroom and found a half dozen semiautomatic firearms, a poster of a Nazi storm trooper, a fish tank full of mice, a pair of high heels coated in dried blood, and—the items that disturbed them most of all—seventy-one crush videos, which, Suffolk County prosecutors claimed, Capriola was selling through his Crush Goddess website and ads in porn magazines.14

Suddenly, America was in a pincer grip. Seeping across the map like the red tide in a cold war animation, crush freaks were advancing on the heartland from both coasts. Someone had to stand and fight. Michael Bradbury, the Ventura County district attorney, held a press conference along with representatives of the Doris Day Animal League. On a sunny day in Simi Valley, in front of large-format images of insects, kittens, guinea pigs, and mice being squashed under women’s feet, they launched the campaign to fast-track House Resolution 1887, a federal bill designed to criminalize the production and distribution of crush videos.15 The sponsor of the bill was Representative Elton Gallegly, a seven-term California Republican known for his energetic support of the citrus and wine industries’ campaign to eradicate the glassy-winged sharpshooter leafhopper (as well as a record on immigration so hawkish that it led to his induction into the U.S. Border Patrol Hall of Fame).16 Gallegly described the fetish as “one of the sickest and most demented forms of animal cruelty that I’ve ever been exposed to.”

The campaign presented crush as a “gateway fetish.” Just as cannabis leads inexorably to crack, its spokespeople argued, fetishists might begin innocuously enough with grapes and worms, but—step by step—they will be drawn up the ladder of Creation, until, in Bradbury’s lurid scenario, it won’t be long before someone “pay[s] $1 million to have a kid crushed.”17 To underline the point, one of his deputies testified to having seen a video in which a baby doll was trampled underfoot. Seventy-eight-year-old former child star Mickey Rooney piped up. “Put a stop, won’t you, to crush videos,” he begged. “What are we gonna hand our children? This is what we’re going to hand down, these videos, crush videos? God forbid.”18

As the bill headed to Congress, Jeff became the go-to guy for the entire media. For a few intense weeks, he was inundated with requests from radio stations, magazines, and newspapers. Perhaps seduced by that peculiarly American brew of idealism, exhibitionism, and celebrity seeking, he ignored the advice of a lawyer friend. Perhaps naïvely, he made himself available to all requests. (“I thought, Well, that’s not fair because, first of all, we didn’t do anything wrong….”) Still, for a while at least, he was able to give himself some cover. In interviews, he declared that he had ceased production of videos until all legal questions were resolved, and he drew a sharp line between the “vermin” featured in his own movies—specifically insects—and the mammals with which Bradbury, Gallegly, and Rooney were especially preoccupied. He didn’t believe crush videos of domestic mammals actually existed, he said, but if they did, he certainly had no interest in them. I at first assumed this demarcation was a legalistic maneuver Jeff was using to protect himself in the midst of a dangerous moral panic. But then I realized it was a distinction fundamental to his fetish. Of course, he maintained, he had no interest in stomping on domestic pets. Even rodents, he told the Associated Press, are “too furry, too animal-looking.”19

Jeff’s argument was the same now as it had been on the talk show circuit in 1993. He took aim at those like Tom Connors, the Ventura County deputy D.A., who claimed it was the method, not the fact, of killing animals that was at issue. In Jeff’s view, it was the very fact of killing animals that was wrong. The method was irrelevant. His critique was systemic. (“Look,” he told me, “America’s seventy-five percent grossly obese—you don’t think they got there eating fuckin’ vegetables?”) Killing animals was endemic to capitalist society. What was at stake in the fight over crush videos, he argued, was the hypocrisy of a society that turned a blind eye to the daily mass slaughter of all kinds of animals but threw up its arms in horror when a tiny number of people killed for sexual pleasure. Jeff, it turned out, was a vegan and an animal rights activist.

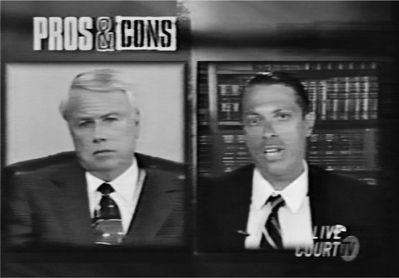

“What about the fur industry, what about fishermen, what about the cattle industry?” he asked the BBC. “You can kill anything you want, basically, in any manner you want if it’s for food or for sport or for fashion, but you cross the line when you do it for sexual gratification.”20 And anyway, he added, if we’re honest, don’t we all know that the excitement of the bullfighter and the thrill of the hunter is a sexual thrill, a sexual excitement. They’re getting off on killing. The problem here is that crush freaks don’t pretend otherwise. “I thought,” Jeff told me, “I’m going to tell the world it might be reprehensible and gross, but it’s not anything worse than what everybody does on a day-to-day basis.” Or as he put it in a live encounter with Elton Gallegly on Court TV: “Our fine Congressman says there’s a humane way to kill vermin. That’s a colloquialism. Killing is killing. You kill them fast, you kill them slow. I wonder if the Congressman has ever seen a sticky trap or a snap trap. There’s nothing humane about them.”21

Gallegly’s bill sailed through Congress by a vote of 372-42 in the House and unanimous acclaim in the Senate. Nonetheless, there was significant unease about the law’s First Amendment implications. This was a bill written to criminalize content—“the depiction of animal cruelty”—and before it reached the floor of the House, it was substantially revised in the Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Crime to allow exceptions “if the material in question has serious religious, political, scientific, educational, journalistic, historic, or artistic value.”22

Despite that, a number of representatives, most notably Robert Scott (D-Va.), argued strongly that the bill was still too broad (“Films of animals being crushed are communications about the acts depicted, not doing the acts”) and failed to demonstrate compelling government interest (a test established by the Supreme Court in 1988 for First Amendment cases).23 On this point, it was clear from the Supreme Court’s upholding of the rights of the Santería church of Lukumí Babalu Aye in 1993 against a Hialeah, Florida, city ordinance banning animal sacrifice that, despite the arguments of animal rights activists, the welfare of animals was not recognized in law as sufficient grounds to restrict First Amendment speech.24

So what might constitute the compelling state interest in crush videos? Representative after representative rose in support of Gallegly’s bill to secure the link between violence toward animals and violence toward people. They invoked spousal abuse, elder abuse, child abuse, and even school shootings. Congressman Spencer Bachus (R-Ala.) summarized the logic of this animal protection legislation most succinctly of all: “This is about children,” he informed the Speaker of the House, “not about beetles.”25

Still, the real headline grabbers were the celebrity serial killers. What did Ted Bundy, Ted “the Unabomber” Kaczynski, and David “Son of Sam” Berkowitz have in common? Gallegly had the answer: “They all tortured or killed animals before they started killing people.”26

It made good copy, but I doubt even the politicians believed this link between crush videos and mass murder. After all, many of them had already listened to Susan “Minnie” Creede, the D.A.’s undercover investigator, as she testified before the Subcommittee on Crime about the psychology of the crush fetishist. After almost a year in the Crushcentral chat room, Creede was an expert witness.

“They spoke about their fetishes and how they developed,” she told the committee.

For many of them the fetish developed as a result of something they saw at a very early age, and it usually occurred before the age of five. Most of these men saw a woman step on something. She was usually someone who was significantly in their lives. They were excited by the experience and somehow attached their sexuality to it.

As these men grew older, the woman’s foot became a part of their sexuality. The power and dominance of the woman using her foot was significant to them. They began to fantasize about the thought of being the subject under the woman’s foot. They fantasized about the power of the woman, and how she would be able to crush the life out of them if she chose to do so. Many of these men love to be trampled by women. Some like to be trampled by a woman wearing shoes or high heels. Others like to be trampled by women who are barefoot. They prefer to be hurt and the more indifferent the woman is to their pain, the more exciting it is for them.

I have learned that the extreme fantasy for these men is to be trampled or crushed to death under the foot of a powerful woman. Because they would only be able to experience this one time, these men have found a way to transfer their fantasy and excitement. They have learned that if they watch a woman crush an animal or live creature to his death, they can fantasize that they are that animal experiencing death at the foot of this woman.27

Congressman Gallegly also heard much the same thing from Jeff Vilencia during their encounter on Court TV. “The viewer identifies with the victim,” Jeff stated flatly in an attempt to counter Gallegly’s alarming claim that crush freaks were dangerous sadists. The fetish “starts in childhood, when the child observes an adult person, usually a woman, stepping on an insect,” he continued, echoing Creede, his legal nemesis. “He becomes sexually aroused, sort of by happenstance, and as he becomes an adolescent, he eroticizes his behavior in his sexuality, and it becomes a part of his love map—” (“His love map?” interrupted the host incredulously.)

Without an origin story, how else can Jeff refute Gallegly’s fantasies of the crush freak as the proto-serial killer and the insect as the proto-baby? There’s no space for refusal. At the center of a frighteningly unstable public debate (TV host: “Jeff Vilencia, are you a tiny bit afraid you’re going to be prosecuted? You’re the one producing these films”), explanation is Jeff’s only option. He has to explain that his fetish has a specific history that ties it to specific objects, that it is masochistic, and that masochism—as the philospher Gilles Deleuze argues in his famous discussion of Sacher-Masoch—is not a complementary form of sadism but part of an entirely distinct formation. A “sadist could never tolerate a masochistic victim,” writes Deleuze, and “neither would the masochist tolerate a truly sadistic torturer.” The distinctions abound: the masochist demands a ritualized fantasy, he creates an anxiety-filled suspense, he exhibits his humiliation, he demands punishment to resolve his anxiety and heighten his forbidden pleasure, and—quite unlike the sadist and with Sacher-Masoch as the locus classicus—he needs a binding contract with his torturess, who, through the contract (which, in truth, is no more than the masochist’s word), becomes the embodiment of law.28

But if only it really were that straightforward. When, in a reflective moment, Jeff tells me that the one thing he learned from all of this was that “women are really cruel, just really evil, man,” and he says it bleakly, with not a hint of teasing, I see that I haven’t quite got the hang of this, and I’m not sure that Deleuze has either. Isn’t the point that cruelty is part of a compact, that there is agreement, tacit or explicit, about boundaries and needs? Isn’t that what all Jeff’s banter with Elizabeth and Michelle is probing? Admittedly, at the end of Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs, Wanda lets loose her Greek lover on Severin with the full force of his hunting whips. It’s horrible, and unexpected too. But it’s also a momentous effort on her part to finally break his dependency, to enforce that break by unambiguously stepping outside the contract. Wanda strains for the gesture that will free them both without the death of either. Under this assault, writes Sacher-Masoch, Severin “curled up like a worm being crushed.” All the poetry is whipped out of him. When it is finally over, he is a changed man. “There is only one alternative,” he tells the narrator, “to be the hammer or the anvil.” Henceforth, he’ll be the one doing the whipping.29

But could this be what happened to Jeff too? Only differently? Did the furies of Fox News strip him of his pleasures? Was that tense but playful self somehow swept away in the storm of disgust that poured down on him? The wrong kind of suffering. Game over, lights on. Cruelty is suddenly just cruelty, Michelle is just Michelle, stomping on animals and maybe actually enjoying it. No longer a goddess, no longer exciting. Just mean.

Such a long road to get here. A road paved with explanation. Explanation was straightforward for investigator Susan Creede. Her task before the House subcommittee was to manufacture an object that could be acted upon by the law. Think of her as the forensic expert narrating the corpse. But it’s so much more complicated for Jeff Vilencia. It’s not simply the demands of the moment that force him to speak Creede’s language. Among the DVDs, videos, books, audiotapes, unpublished writings, and press clippings he sent me when we first talked was an unexpected item: a three-page article he’d written called “Fetishes/ Paraphilia/Perversions.” The essay begins programmatically: “Perversions are unusual or important modifications of the expected pattern of sexual arousal. One form is fetishism, of which crush fetishism is an example.” It goes on to describe seven theories of fetish formation (“oxytocin theory,” “faulty sexualization theory,” “lack of available female contact theory,” and so on) and includes as an appendix a discussion of the seventeen “possible stages of fetish development basic to the modified conditioning theory” which both Jeff and Susan Creede used to explain the birth of the crush freak to Congressman Gallegly.

At the time I didn’t understand why Jeff wanted me to have this essay. Nor did I understand why he had dedicated Smush to Richard von Krafft-Ebing, the pioneering nineteenth-century Viennese sexologist whose Psychopathia sexualis documented “aberrant” sexual practices as medical phenomena. But then I got to the second volume of The American Journal of the Crush-Freaks, published in 1996, which is subtitled: “Just where do we fit in, in all of this?” In the introduction, Jeff writes:

Imagine all of the shame you would feel having no one to talk to about your desires. It is as alone as one could feel. You might as well be stranded on an island someplace.

Well those dark days are behind us now. As we move towards the 21st century, and as various sexual groups have come out over the years, I cannot see any reason that people should feel shame any more….

There are more choices today than there ever were. When I was a kid, I was a crush-freak, only I didn’t know what to call myself. Today, I know who I am, and more important, I know why I am.

It was that why that mattered: “As a child I had a knack for getting in trouble. As an adult I look forward to telling the world my sexuality. I am willing to take all my critics on. I have appeared on television and radio, major newspapers, and adult fetish magazines. I have spoken at four different universities in Southern California. I also produce videotapes that I sell to my fellow crush-freaks for masturbation purposes. Trouble comes to town and his name is Jeff Vilencia!”30

6.

When Bill Clinton signed H.R. 1887 into law on December 9, 1999, he issued a statement instructing the Justice Department to construe the act narrowly, as applicable only to “wanton cruelty to animals designed to appeal to a prurient interest in sex.”31 In the years since, perhaps wary of the legislation’s frailty, prosecutors have used it only three times. On each occasion—and contrary to Clinton’s directive—they wielded it against distributors of dog-fighting videos. In July 2008, a federal appeals court struck down the law, agreeing with Robert Scott that the First Amendment does not allow the government to ban depictions of illegal conduct (as opposed to that conduct itself). In October 2009, the Supreme Court heard an appeal from the government backed by animal rights groups.32

No matter the fate of H.R. 1887, for Jeff Vilencia there is no going back from those few hot weeks in the fall of 1999. Jeff tells me how his radio and TV interviews were edited to make him monstrous, how he tried to play the unedited tapes for his family but they believed only the broadcast versions. He tells me how his niece—in the name of her new baby—led his mother on a tour of websites that featured crush videos or specifically targeted him. “I lost friends, my brothers and sisters … I mean, it was just a horrible ordeal. I was almost isolated. I mean, I had no friends, no one wanted to talk to me, you know, and I just thought … you know …” He trailed off. He tells me how he quit video making entirely. “I just got to the point of giving up on life.” He tells me how it’s since been impossible to find a job because these days employers automatically Google their applicants.

So here we are on the featureless patio outside that suburban Starbucks, and he’s telling me that he learned two things from all this: that women are “really cruel bitches” and that “perversions are best left in the closet, buried in the dark.” He’s telling me about the men who were inspired by his example to come out to their girlfriends and wives and how in all cases their lives fell to pieces. And he’s telling me that he needs love too and that now he has someone who gives it to him but doesn’t want him talking about all this anymore. And he checks my watch nervously, leans back in his chair, looks out across the parking lot, sighs, and says softly: “Seems like a dream, man …”

7.

Go to YouTube, search for “crush videos,” and see what you get. There’s a lot up there. Short, poor-quality home videos of women stepping on crickets, worms, snails, lots of squishy soft fruit. Some of the clips have had tens of thousands of views, most have a few thousand, one has a couple of hundred thousand. It’s a long way from the underground trade of expensive Super 8 film in the 1950s and ’60s and even from the back-of-the-porn-mags sales in the ’80s and ’90s. If YouTube doesn’t meet your need, it’s easy to find longer and more professional product on the many specialist websites that are trading entirely openly despite Gallegly’s legislation.

Gallegly himself allowed for this future. At one point in the debate on H.R. 1887, he took the floor to clarify a crucial point. “This has nothing to do with bugs and insects and cockroaches, things like that,” he told his colleagues. “This has to do with living animals like kittens, monkeys, hamsters, and so on and so forth.”33 For a moment, there’s something on which everyone can agree. There are animals that matter, and there are things that don’t. And then Gallegly draws breath, and before you know it, he’s off again about Ted Bundy, the Unabomber, and the safety of our children.